In 1998, the fourth Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, established the Buenos Aires Plan of Action (BAPA). The core issues would be resolved for the sixth Conference of the Parties (COP-6) in November 2000. The second is a virtual case where the US is supposed to be part of the Bonn-Marrakech Agreement, along with all the others. The parties.

In the current situation, the US is outside the negotiation process and has no commitment to reduce emissions. We shed light on the potential market power of the former countries arising from the Bonn-Marrakesh Agreement. The study focuses only on CO2 emissions and does not take into account reductions in emissions of other greenhouse gases (GHGs) mentioned in Annex A of the Kyoto Protocol.

The first part of this study deals with the economic consequences of the Kyoto Protocol which was agreed in 1997. Finally, using the results of the ASPEN software, the fourth part deals with the analysis of the restriction on the trade of hot air and the impact and power of the FSU and EEE market. They are included in the calculation of 'total emission reductions', as they are actually actual emission reductions.

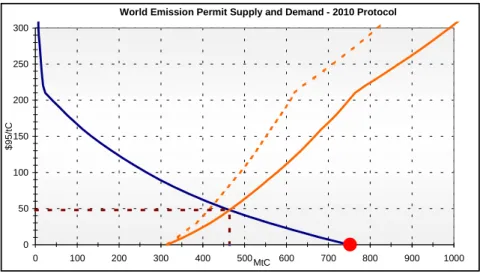

The starting point of the supply curves corresponds to the amount of warm air in FSU and EEE: up to 315 MtC, FSU and EEE can deliver emission reductions at zero marginal costs.

The Hague ‘missed compromise’ (MC)

The Bonn Agreement

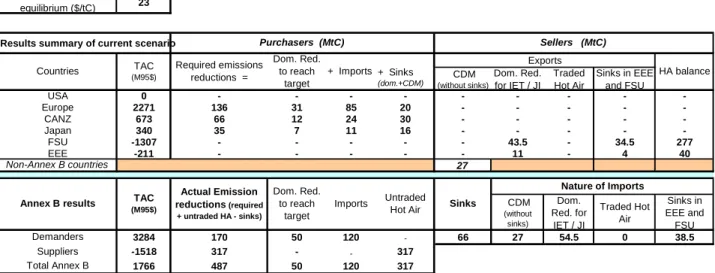

This clearly shows that the Bon-Marrakech Agreement would not have brought significant changes from the compromise discussed in The Hague, if the US had not withdrawn from the negotiations in between. Since the US did not participate in the Bonn-Marrakech Agreement, the other Annex B countries face a strange situation: the supply of emission reductions is greater than the demand (Table 4). On the demand side, Annex B importing countries or regions need to reduce their emissions by 237 MtC, according to POLES calculations.

On the supply side, there is a surplus of hot air and sinks for trade of 353 MtC from FSU and EEE. Globally, Annex B countries in the 'Kyoto Protocol without the US' could thus meet (and outperform) their target without any emission reduction measures: emissions b. In addition, Annex B countries would not be required to implement CDM projects in developing countries.

As Resources For the Future puts it: “The Kyoto Protocol without the US is like musical chairs with one too many chairs – there's a lot of marching around but nothing happens” (Kopp, 2001). In fact, the amount of hot air traded is very likely to be less than what is available. Although it is theoretically possible to face the situation described in Figure 2, it seems unlikely that the various parties will agree on a free exchange units to reduce emissions from FSU and hot air EEO.

Moreover, some importing parties (especially the EU) appear willing to commit to an environmentally important agreement that is only feasible if some of the hot air is not traded. In such a situation, FSU and EEE can benefit from selling only part of their hot air instead of the whole volume, as they are the only sellers of emission reductions among Annex B countries. The limitation of hot air and the potential market power of Russia and Eastern European countries.

The restriction of hot air and the potential market power of Russia and Eastern European countries

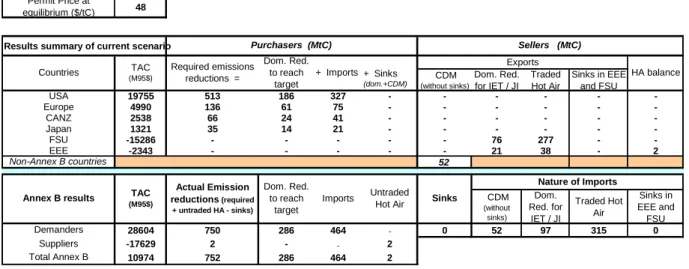

So if they had the market power to do this, they would trade their warm air up to 10% of the total theoretically available warm air. So far, negotiations at the various Conferences of the Parties have not led to any reduction in hot air. But it is not in the interest of FSU and EEE to sell out their hot air during the first commitment period.

Any restriction on trade in warm air clearly means that Annex B importing countries must implement domestic emission reductions in order to meet their targets. But even if warm air is not traded at all, Annex B importing countries will resort to purchasing emission permits, JI projects or CDM projects in addition to domestic measures, because the international price of the permit is lower than the marginal cost of some domestic measures. When the hot air limit is 100% (without trade in the first target period), the import of reduction units still accounts for about 60% of the targets (Chart 5).

The nature of imports changes significantly, along with the extent of hot air restrictions, but not the geographic origin. If the trade in warm air is partially (up to 55%) or completely excluded, the permit price is positive. In that case, we analyze the impact of the total withdrawal of hot air from the trading system during the first commitment period in the Bonn-Marrakech Agreement (case BM1,0).

In the case that FSU and EEE do not trade their hot air at all, the permit price is $23 (Table 5), which is close to the MC and BM0 cases without US participation. We now move on to the situation where FSU and EEE exercise their market power by selling only 10% of their hot air (see graph 4): case BM1,1. Nevertheless, these benefits are very close to those obtained in case BM1,0 when no hot air is traded at all.

From examples i and ii, it appears that FSU and EEE have an interest in keeping all their hot air in the first target period. First, exercising their market power does not gain them much: the maximum benefits from this process appear to be about the same as the benefits obtained from JI projects alone (ie when no hot air is traded). Then, the more hot air there is, the more the limit for FSU and EEE to meet Kyoto emission reduction commitments can be reduced (depending on the limit they would accept in the second target period).

From an environmental perspective, it is clear that efficiency, in terms of overall emissions reductions, would be highest in the first commitment period if hot air savings were made. But this option would postpone the issue of hot air management to the next commitment period.

Conclusion

Finally, it is important to emphasize that our analysis assumes that all Annex B Parties except the US have ratified the Kyoto Protocol. Furthermore, our analysis is only relevant if FSUs and EEOs meet the eligibility requirements necessary to participate in the flexibility mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol.

Bibliography

Sinks capped at 3% of base year emissions

Sinks in the Bonn-Marrakech agreement

Impact of the CDM access factor

GU %CJKGTU FG 4GEJGTEJG FG N +'2'