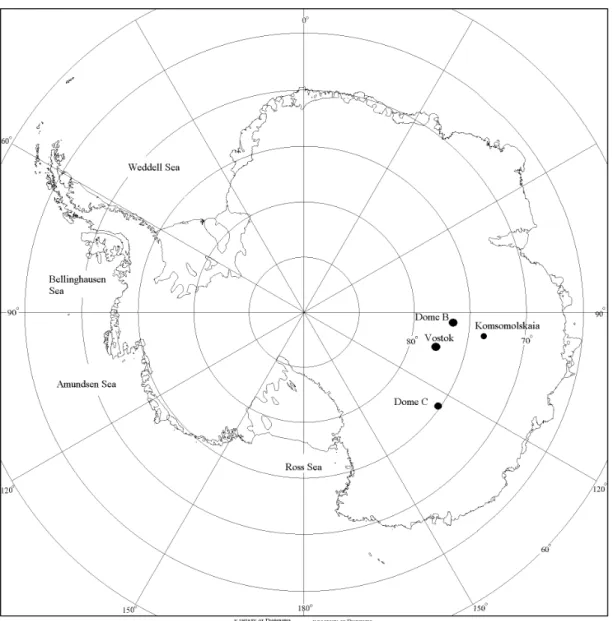

143Nd/144Nd isotopic signature of ice core dust and sediments from the Potential Source Areas (PSA) of the Southern Hemisphere. The longest climate records from ice cores can be recovered from the low accumulation sites of the high East Antarctic Plateau. Dust variability was investigated through a physical approach, consisting of measuring the total dust concentration and its size distribution, each of these indicators holding different information about the paleo-dust cycle (Chapter 3).

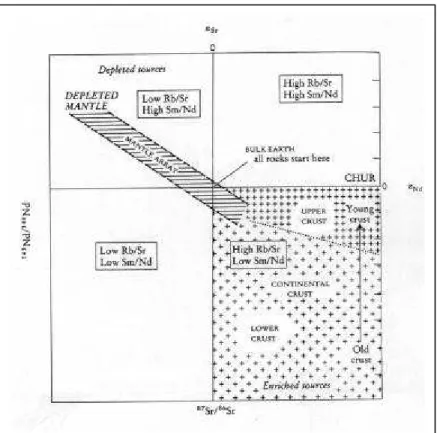

This part of the research work was carried out partly c/o the CEREGE laboratory in Aix en Provence (France) and c/o the Max Plank Institute (MPI) in Mainz. The chapter concludes with a summary of the climatic and atmospheric narratives from the Vostok ice core for the last four glacial/interglacial periods. The chapter discusses the utility of the 87Sr/86Sr versus 143Nd/144Nd isotopic signature of dust as a tracer of sediment provenance.

Quaternary climate variability

8 In zonal standing wave analysis, wave number 1 corresponds to the eccentricity of the polar vortex. 3 The precision of the analysis refers to the deviation of a measurement from the true value. They are collected respectively in the lower and upper part of the valley.

The change in the palaeoenvironment of the source regions is important in terms of the dust cycle. Wenzens (1999) reports a list of nine glacial advances that may have occurred in southern Patagonia (from 48°S to 51°S) at the time of the European YD. Second, what accounts for the increase in particulate matter over the Holocene period.

The highest fashion values are observed in the late Holocene, from about 2 to 7 kyr B.P. Paleovegetation records also suggest increased storms and cloud cover in the second half of the Holocene. The EDC dust record provides new insights into past climate dynamics in the Southern Hemisphere.

Marden CJ, Clapperton CM (1995) Ice field fluctuations in Southern Patagonia during the last ice age and the Holocene. Spectral analysis of the data (not shown) reveals several bands and one of them peaks at 1300 years (with F-test confidence levels >95%, using the Multitaper method). Each millennial-scale oscillation in the Holocene portion of the EDC ice core averages 30 samples.

The change in the size distribution provides some indications regarding the long-range transport of the continental aerosol. In addition, ice-free areas in Antarctica likely increased during the Holocene. The origin of the observed millennial-scale variations in the climate system is still not understood.

Correlation of late Pleistocene glaciation in the western United States with North Atlantic Heinrich events. Indeed, the size of the mineral aerosol in the atmosphere decreases with altitude (Tegen and Lacis, 1996).

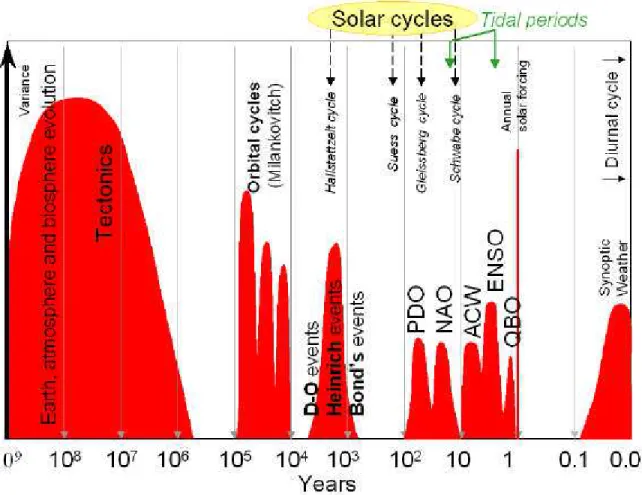

The timescales of climate changes

Quaternary environmental changes: a short overview

The cold phases of the Pleistocene were accompanied by the expansion of the permafrost boundary. The position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), the Western Belt, and the main oceanic and continental anticyclones changed within the Quaternary in connection with changes in wind strength (§ 1.6). Past atmospheric circulation can be reconstructed using multiproxy indicators for different regions of the world.

Local hydrological changes The climatic fluctuations in the Quaternary had regional and local responses in river, lake and groundwater fluctuations. The environmental changes induced by temperature and precipitation fluctuations induced variations of the non-marine plant assemblages and the animal populations. The first evidence of Homo Sapiens is dated around 300-200 kyrs B.P.; human development, migrations, development and cultural progress have always been closely linked to climatic and environmental changes.

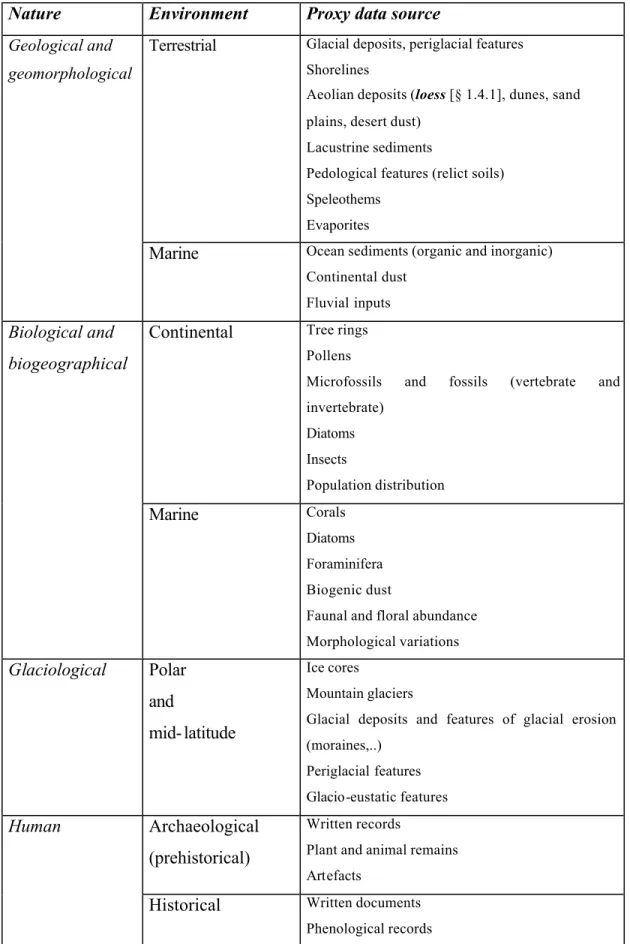

The natural archives of paleoclimate history

The Pampean loess is similar in texture and color to loess of the Northern Hemisphere, but differs from this in its mineralogical composition6 (Gallet et al., 1998) as it is mainly derived from volcanic parent rocks7. Other paleoeolian features of late Quaternary origin can be found in southern South America further south, in Patagonia, where wind action allowed the removal and transport of the weathered rocks within the southern plains. 7 It is assumed that the Andean explosive volcanism had a direct influence on the composition of the Argentine loess (Sayago et al., 2001).

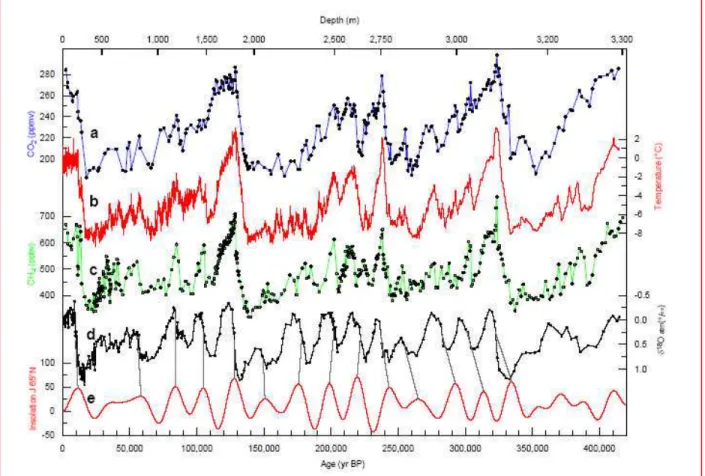

The first-order variability of the marine and terrestrial aerosols is anti-correlated with the temperature recording (Fig. 1.7d and 1.7e). Much of the temperature record's variance is concentrated in the 100 kyr and 41 kyr bands, which correspond to the eccentricity of Earth's orbit and the tilt of its axis. The latter is in phase with the annual solar irradiance at the Vostok site, suggesting a close relationship between annual solar irradiance variability at high southern latitudes (i.e. on the order of 7%). and the temperature at Vostok.

Southern Hemisphere atmospheric circulation

SH is under the influence of two main wind regimes that circle the globe: (1) Perma-Easterns, which mark the central position of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), and (2) Westerlies. However, the dominant feature of the SH atmospheric circulation is the large tropospheric gyre of the westerly winds, which reaches its maximum in the upper troposphere. During the so-called high phase of the Southern Oscillation, pressure rises in the eastern Pacific and falls over Indonesia.

In the analysis of zonal standing waves, the eccentricity of the polar vortex is related to wavenumber 1. A descending limb of the Walker circulation develops over the former region and an ascending limb in the latter. In parallel, the northern margin of the Westerlies shifted 5 to 10 degrees north relative to its current position (Iriondo, 1999).

Mineralogical nature of aeolian dust

Primary and secondary aerosols can interact in the atmosphere to create complex mixtures (e.g. Raynaud et al., 2003). The latter is the subject of interest for this work, and the terms continental, aeolian, or mineral dust will be used interchangeably. An important second-order effect of atmospheric dust deposition relative to particle mass is the fractionation of heavy minerals: due to the rapid gravitational settling of heavy minerals (such as magnetite, garnet, hornblende, zircon, rutile, epidote), they become relatively more abundant in sands and sandstones and , in general, in sediments with an overall larger grain size (Taylor and McLennan, 1987).

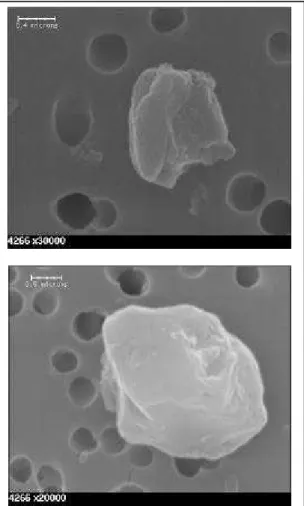

Among the clays, illite is the most abundant (>60%) in Vostok and South Pole ice (Gaudichet et al., 1992), while smectite, chlorite and kaolinite vary in smaller proportions.

The role of mineral dust on climate

The large specific surface areas provided by airborne minerals result in abundant crystallographic sites for heterogeneous condensation and subsequent reaction of gaseous species (e.g., Dentener et al., 1996). Additionally, dust can affect the formation of cloud droplets, with subsequent effects on cloud brightness and rainfall (e.g., Zhang and Carmicael, 1999). One important indirect radiative forcing is associated with the role of dust particles, and clay in particular, as ice-forming nuclei (e.g., Rogers and Yau, 1989).

Mineral dust also plays an important role in terrestrial (eg, Swap et al., 1992) and marine (eg, Hutchins and Brunland, 1998) ecosystems by providing nutrients. For example, iron represents the limiting nutrient for phytoplankton communities in some ocean regions (eg, Fung et al., 2000; Falkowski et al., 1998). Substance imports can therefore potentially influence the global carbon cycle and greenhouse gas content in the atmosphere.

The knowledge for present time

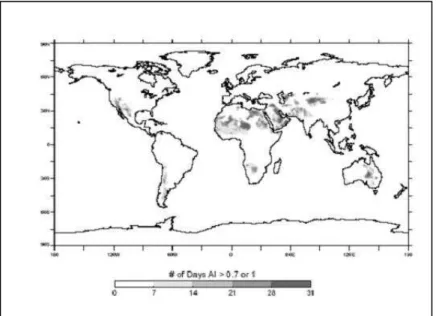

Atmospheric dust load

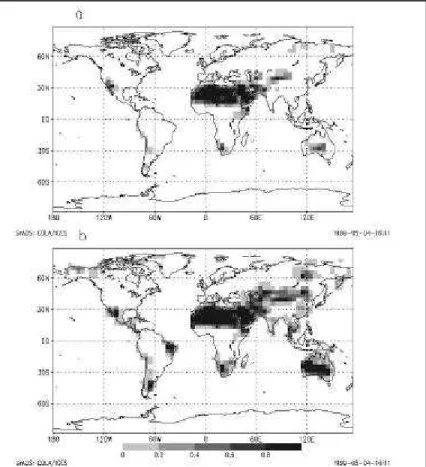

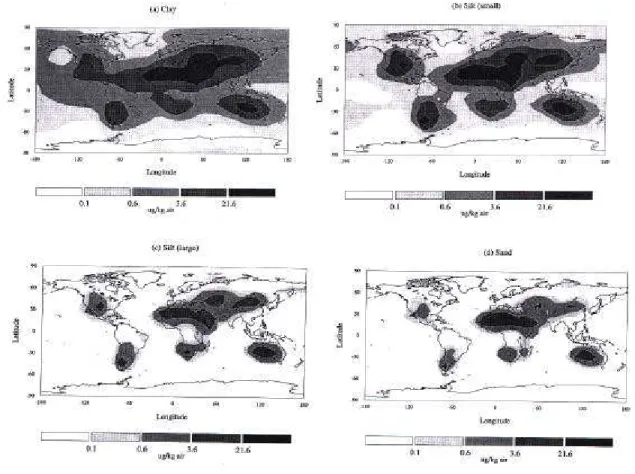

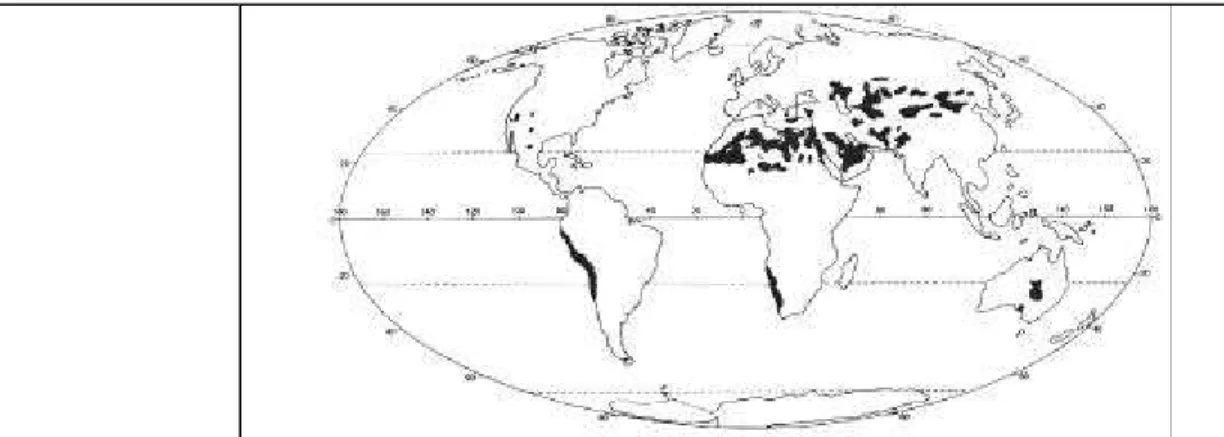

Sand dune systems do not appear to be good sources of long-transported dust (Prospero et al., 2002). The authors found an explanation for this in the flat topography of the continent and the lack of renewal of small particles (§ 2.2.1). For South Africa (Fig. 2.4), a continuous source of dust is located in Botswana in the region centered at 21ºS, 26ºE.

The former is located in the Bolivian Altipiano, about ∼20°S and 68°W, in an arid intermontane basin located at about 3750–4000 m elevation that includes two of the world's largest salt flats (salars). A large part of the Altipiano was occupied in the Pleistocene by a lake, the sediments of which are exported today by the strong winds that blow over the region. It can be noted that the most active area lies in the western part of this region.

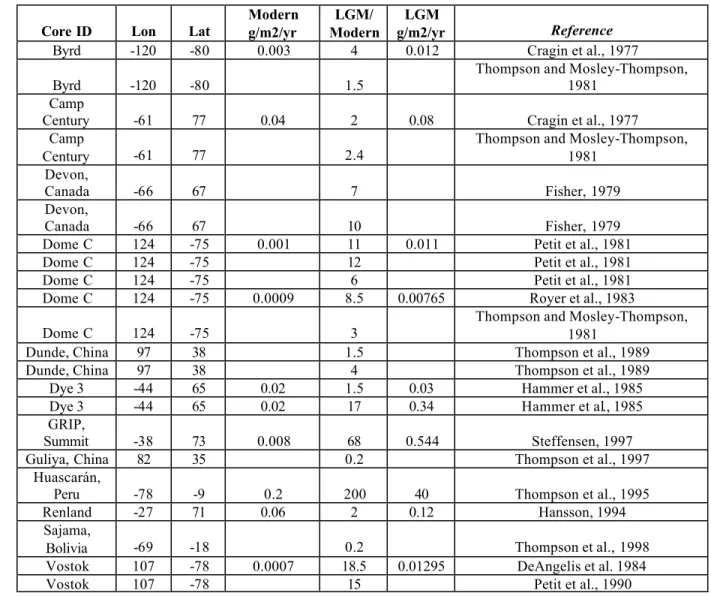

The LGM atmospheric dust load: evidence from paleoclimate proxies

Several aspects of the glacial climate must be considered to understand the reasons for the observed increase in the dust cycle during the LGM. Large ice sheets covered most of the Northern Hemisphere at mid- and high latitudes and also developed in the Southern Hemisphere (see box. 2). The cooler and drier climate affected land surface conditions, generating a reduction in the total forested area and the expansion of the area of grass- or shrub-dominated vegetation (Tegen et al., 2002a).

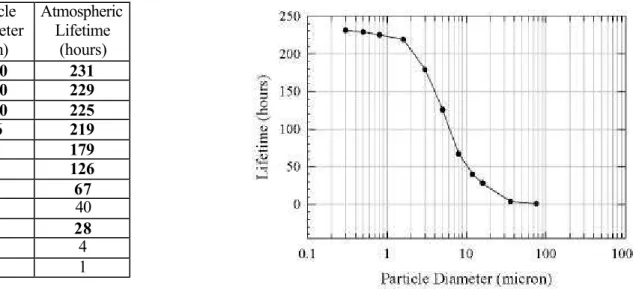

Adding exposed continental land areas as an additional source also fails to account for the magnitude of the observed changes (Andersen et al., 1998). When it is necessary to determine the strength of a continental scale source, the areal extent of the dust supplying areas must also be taken into account. D’Almeida and Schutz (1983) observed a direct relationship between surface wind speed and airborne dust size distribution for the >10 µm size fraction.

The long-range transport

The horizontal dimension

The EDC core climatic record is inferred from the isotopic composition of the ice, and the profile has been described in Jouzel et al. The latter corresponds to the end of the Younger Dryas in the Northern Hemisphere (11.5±0.2 kyr B.P.), marked by a peak in methane concentration (Chappellaz et al., 1993). This may also explain the efficient sorting of the particles and the low variability in the size distribution parameters of LGM dust.

Recently, the change in dust size evolution over the last 27 kyr and part of the Holocene in the EPICA-DomeC ice core revealed some new aspects (Delmonte et al., 2002a, 2002b).

Sm-Nd dating and Sr-Nd isotopic signature of a bedrock inclusion

Supplementary tables

List of publication outcome from this thesis