VAULTED CONSTRUCTION IN ROME Scholars expert in Roman architecture have long

After first considering the building methods documented in Rome itself, it goes on to illustrate building techniques in the Peloponnese, emphasizing their particularity, the process by which they were adopted and possible reasons for their success.

BUILDING ACTIVITY AND PATRON- AGE IN THE PELOPONNESE

ROMAN VAULTING AND CONSTRUC- TION IN THE PELOPONNESE: CASE STUDIES

ROMAN VAULTING IN THE PELOPON- NESE: EXCEPTIO PROBAT REGULAM IN CASIBUS

In 1984, when the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma started the restoration of the northwest facade of the Domus Tiberiana on the Palatine Hill, my brother Massimo and I were employed to survey Roman buildings. The study of historical construction had already begun in France in the second half of the 19th century. He also pointed to many construction methods from early Byzantine architecture, not realizing that the precursors of the construction techniques he described were to be sought in the Peloponnese.

I found the most convincing method of analyzing Roman building techniques in Greece to be an examination of vaults that clearly rep‐. In Greece, apparently little has survived and most Roman ruins have lost their vaults. Many of the sites we examine here have been published only partially or not at all.

Giovannoni analyzed two crucial moments of the construction: the first was the decentering, when the concrete had hardened but not yet completely hard. The second was the analysis of the cracks created by a voussoir within the monolithic mass of the vault13.

VAULTED CONSTRUCTION IN ROME

Roman mortared masonry

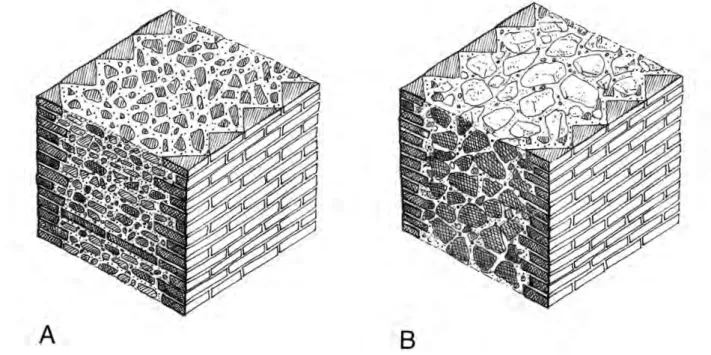

It was described by Vitruvius (2.3,3), who also pointed out the differences between the Greek and Roman building techniques, namely from the fact that the Greeks tied the faces to the core of the structure to create one solid structure, while the Romans created wall coverings to cover the rubble masonry, making it a tripartite structure with two faces and a core. However, it was necessary to avoid that the cladding of the wall separated from the core. Domitian, when the experiments with the use of bricks gave the first important results to improve the rigidity of walls and vaults.

From the time of the 1st century BC, the quality of the walls improved hand in hand with the development. The main difference from the mortared rubble used in previous mortared masonry works lies not only in the way in which the material is laid to form the wall, but also in the composition of the mortar. The layers were not structurally distinguishable, as the slow process of hardening of the mortar allowed in-

However, although the masonry in Greece was of lower quality than the structures in Rome, it had a note. The mortar took a longer period to harden due to the lack of hydraulic properties, but at the end of the process it was as good as the masonry using volcanic aggregates.

Concrete vaulting in Republican and Imperial Rome .1 Republican period.1 Republican period

- Imperial Period

- The use of brick for vaulting in RomeRome

This structure had to be strong enough to withstand the weight of the concrete mass. Brick concrete was used in the buildings of Augustan Rome as early as the end of the 1st century BC. However, there is evidence of bricks used in vaults in some of the capital's grandest buildings.

The purpose of using solid brick arches in Colosse was structural, as pointed out by L. This construction reflects the use of ribs built into the concrete mass, another of the important innovations that was adopted in the growth-. Ribs in Rome were more like brick-faced opus caementicium arches than solid brick arches, as they were formed by two-footed cuts laid radially in concrete vault intrados and spaced apart from each other (fig. 4.15).

Outside Rome, solid brick arches were also used, but occasionally and only where there was a close connection with Rome, as for example in the case of Baga. The aforementioned use of solid brick arches in the Colosseum indicates that it is by the time of Domitus.

BUILDING ACTIVITY AND PATRONAGE IN ROMAN PELOPONNESE

- The region

- Cities

- The spread of Rome’s architectural models

- The spread of bath buildings

- Imperial and private euergetism

In the new imperial urban centers we find a fusion of sacred and political zones, vol‐. The case of Corinth, the capital of the province of Achaia, where the forum has been extensively excavated. The use of marble as well as the scattering of buildings relating to social customs im‐.

This tribute to the members of the imperial family was intended to underline the political and cultural context. Since the era of Trajan, monolithic columns have been used in the outer parts of the temple. The marble trade was directly related to the expansion of the occupied territories and re-.

ROMAN VAULTING AND CONSTRUCTION IN THE PELOPONNESE CASE STUDIES

Argos

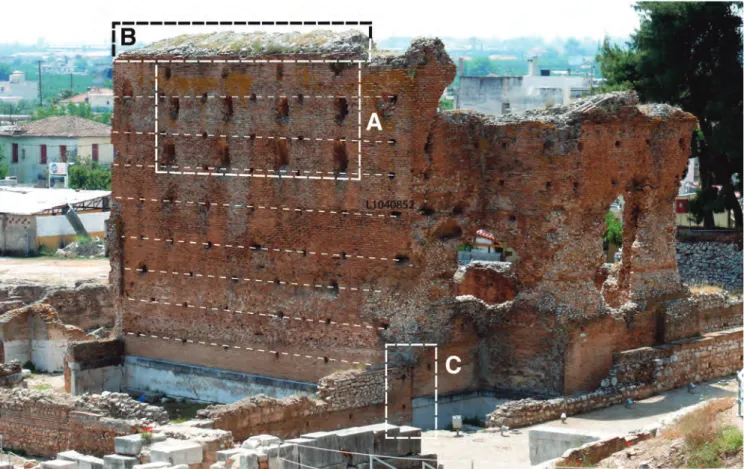

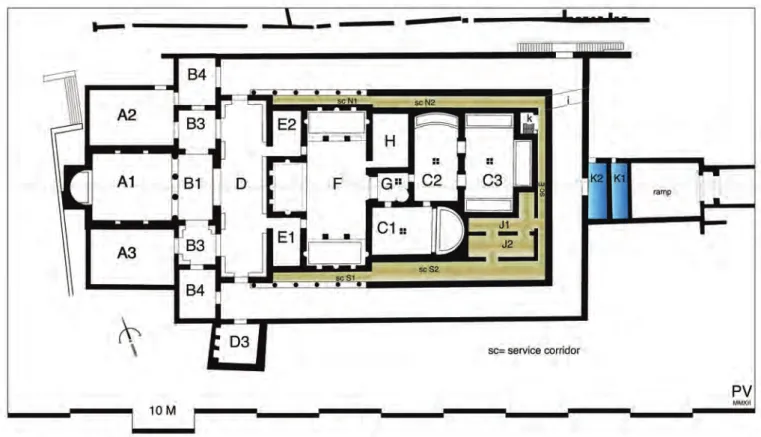

- The Great Hall of the Cult Complex (Bath A)

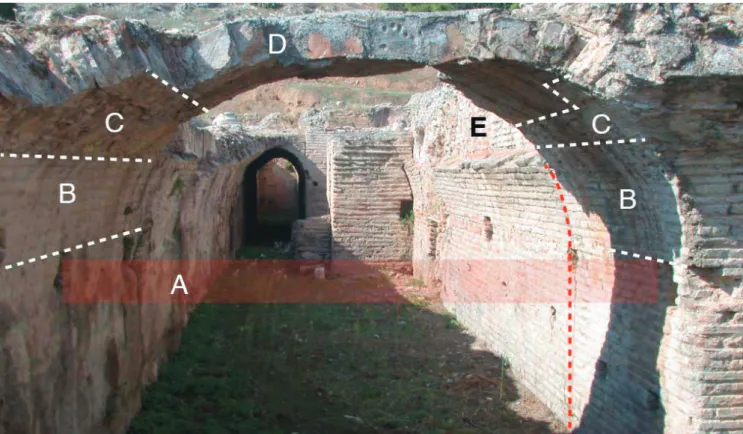

- The Service Corridors of Bath A

- The Access Ramp to Bath A

- The Odeon of Argos

- Hadrian’s Aqueduct

- The Nymphaeum- Castellum aquae on the Larissa hill

- The Drains in the agora

- The Iseum

Troezen

- The Cistern/Castellum acquae

- The Museion

- The Mausoleum RG1

The buildings discussed here are two structures within the city, located near the Hellenistic tower of the diateichisma, and five mausolea outside the city walls. They can be dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries, based on the architectural style and building techniques. On the slopes of the Aderesberg that rises from the plain of Troezen (fig. 3.63), near the Hel‐.

It has a basin waterproofed with crushed brick mortar and a drainage hole, presumably an outlet for water supply to the city. They pass from one side of the wall to the other and were used for scaffolding on both sides of the wall. The so-called Museionis is situated on the plain at the foot of the mountain, not far from cis‐.

The end walls of the rooms were thinner (0.84 m) as they did not have to be included. On the west wall above the impost of the vault, the builders used larger stones (fig. 3.68). View of the upper level of the cistern/castellum aquae with the remains of the vault.

The vault is a continuation of the vertical wall, with the difference that the stones are placed radially and not horizontally. For the same reason, the top of the brick facade was constructed with larger triangular bricks (1/2 square brick) to better adhere to the masonry rubble. RG1 and RG2 are located close to each other on the left bank of the Potami River (ancient Chrisorroas?87), probably in the area of the western necropo.

On the west side the concrete foundation is visible due to erosion of the ground. The detached part of the vault was covered only with broken brick (thickness 14 cm), necessary for watering. The walls were built up to the height of the post of the vault and were covered with yellow.

The walls were built up to the height of the impost of the vault and were faced with yellow

The room was covered by a massive brick vault, today only preserved for a few courses above the impost (fig. 3.73).

Completion of the barrel vault

- The Mausoleum RG2

- The Mausoleum RG3

- The Mausoleum RG4

- The Mausoleum RG5

- The Sanctuary of Asklepios at Epidaurus

- The Odeon of the sanctuary of Epidaurus

- The northwest bath complex

- The northeast bath

- Corinth

- The aqueduct from Stymphalos

- The Great Bath on the Lechaion Road

- The baths north of the Peribolos of Apollo

- The Odeon of Corinth

- Gytheion

- The cistern of the aqueduct

- Isthmia-Zevgolatio

- The baths of Zevgolatio

- Patras

- The mausoleum of Marcia Maxima

- The Aqueducts of Patras

- Thouria in Messenia

- The bath on the Pamisos valley