The first known tax system took place in ancient Egypt around 3000–2800 BCE, during the First Dynasty of the Old Kingdom (Taxes in the Ancient World, 2002). Given the structure of the tax system and the enforcement process, taxpayers face opportunities to reduce their tax payments, or expected tax payments. These private costs depend on government policies, which include, but are not limited to, the setting of tax rates and bases.

The parameters of the tax administration and enforcement policy also matter, but these policies themselves are usually expensive. Such upper or lower limits may apply to retirement but not health care components of the tax. The cost for the stamp was either a fixed amount or a percentage of the value of the transaction.

In the United States, transfer taxes are often levied by the state or local government and (in the case of real estate transfers) may be attached to the recording of the deed or other transfer documents.

Taxes on goods and services

Value added tax (Goods and Services Tax)

Sales taxes

Excises

Tariff

The customs union has a common external tariff, and participating countries share revenue from customs duties on goods entering the customs union.

Fees and effective taxes

Direct and indirect taxes

Thus, a tax on the sale of property would be considered an indirect tax, while the tax on simply owning the property itself would be a direct tax.

Tax avoidance

- Methods

- a. Country of residence

- b Double taxation

- c Legal entities

- d Legal vagueness

- e Tax shelters

- f Transfer mispricing

- Public opinion

- Government and judicial response

More generally, every term in tax law has a vague shadow and is a potential source of tax avoidance (Pasternak M. and Rico C., 2008). In 2008, the charity Christian Aid published a report, Death and Taxes: The True Toll of Tax Evasion, which criticized tax exiles and tax avoidance by some of the world's largest companies, linking tax evasion to the deaths of millions of children in developing countries. (O'grady, Sean, 2008). In 2012, during the Occupy movement, tax avoidance was presented by the organization TaxKilla as a tool of protest by the US government (Cohn, Emily, 2012).

Tax avoidance reduces government revenue, so governments with a stricter anti-avoidance approach try to prevent tax avoidance or keep it within limits. In practice this was not always achievable and led to a constant battle between governments changing the law and tax advisors finding new opportunities/loopholes to avoid tax in the changed rules. To enable a rapid response to tax avoidance schemes, the US Tax Disclosure Regulations (2003) require faster and more complete disclosure than previously required, a tactic used in the UK in 2004.

Canada also uses foreign property income rules to avoid certain types of tax avoidance. The Alternative Minimum Tax was developed to reduce the impact of some tax avoidance schemes. In the United Kingdom, judicial doctrines to prevent tax avoidance began with IRC v. Ramsay (1981), followed by Furniss v.

As a generalization, judges in the United Kingdom before the 1970s, for example, viewed tax avoidance with neutrality; but these days they may view aggressive tax avoidance with increasing hostility. In the United Kingdom in 2004, the Labor government announced that it would use retroactive legislation to counter some tax avoidance schemes, and it has done so on a few occasions since, most notably BN66. It specifically targeted tax avoidance schemes that used offshore trusts and double tax treaties to reduce the tax paid by the scheme's users.

Tax Evasion

The Extent of Evasion

- Hidden Economy as Percentage of GDP, average over 1990-1993

Tax evasion is illegal, so those who engage in it have every reason to try to hide what they are doing. The revenue foregone due to tax evasion also highlights the value of developing a theory of tax evasion that can be used to design a tax structure that minimizes evasion and ensures that policies are optimal when evasion occurs. Tax evasion must be distinguished from tax avoidance, that is, the reorganization of economic activities, possibly at a certain price, in order to reduce tax payments.

Added to this will also be the legal, but undeclared, income that constitutes tax evasion. The fundamental problem involved in measuring tax evasion is that its illegality provides an incentive for individuals to keep the activity hidden. This implies that the extent of tax evasion cannot be measured directly, but must be inferred from economic variables that can be observed.

The obvious problem with survey evidence is that respondents who are active in the hidden economy have every incentive to conceal the truth. First, information collected for purposes other than the measurement of tax evasion may be used. The second common method is to infer the extent of tax evasion, or the hidden economy in general, from the observation of another economic variable.

This is done by determining total economic activity and then subtracting measured activity, which gives the hidden economy. Given a relationship between the amount of cash and the level of economic activity, this allows an estimate of the hidden economy. The table clearly indicates that the hidden economy is a significant issue, especially in the developing and transition economies.

The Evasion Decision

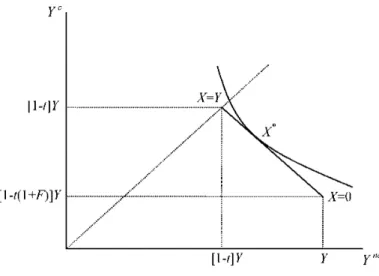

If the maximum return is filed such that X = Y, the taxpayer's income in both states of the world will be [1 -1]Y. Including the indifference curves of the utility function completes the diagram and makes it possible to visualize the taxpayer's choice. In total, differentiating the expected utility function (1) at a constant utility level gives the slope of the indifference curve as.

The slope of the budget constraint is shown in Figure 1, which is given by the ratio between the penalty Ft[Y- X] and the unpaid tax t[Y - X]. In the United Kingdom, the Tax Administration Act sets the maximum fine as 100 percent of the tax lost, which implies a maximum value of F = 1. The next step is to determine how changes in the model variables affect the amount of tax evasion. .

The amount of reported income increases, so an increase in the probability of detection reduces the amount of evasion. This is clearly an expected result, since an increase in the probability of detection lowers the payoff from evasion and makes evasion a less attractive proposition. An increase in the penalty rate therefore results in a reduction in the level of tax evasion.

This and the previous result show that the effects of the detection and punishment variables on the level of evasion are unambiguous. However, when absolute risk aversion is decreasing, the effect of the tax increase is to reduce tax evasion. It is shown how the level of evasion is determined and how this is affected by the parameters of the model.

Effect of Honesty

For example, an increase in the tax rate increases the benefit of evasion and increases χ with the consequence that more taxpayers evade. Second, changing the parameter affects the evasion decision of all existing tax evaders. Putting these effects together, it becomes possible for an increase in the tax rate to lead to more evasion overall.

The discussion of the empirical has drawn attention to the positive correlation between the number of tax evaders a taxpayer knows and the level of that taxpayer's own evasion. This observation suggests that the evasion decision is not made in isolation by each taxpayer, but is made with reference to the norms and behaviors of the taxpayer's general community. Social norms have been incorporated into the model of the evasion decision in two different ways.

One approach is to introduce them as an additional element of the cost of services for evasion. The incremental cost of services is assumed to be an increasing function of the proportion of taxpayers who do not avoid. The consequence of this modification is the strengthening of the division of the population into avoiders and non-avoidants.

To calculate the actual rate of tax evasion, each taxpayer performs the expected utility maximization calculation, as in (1), and evades the smaller of this amount and the previously determined upper limit. The introduction of psychological costs and of social norms can explain some of the empirically observed features of tax evasion that are not explained by the standard expected utility maximization hypothesis. This is achieved by changing the form of the preferences, but the fundamental nature of the approach remains unchanged.

Conclusions

It also raises a whole new set of policy issues, such as the appropriate level of resources to devote to administration and enforcement, and how those resources should be allocated. Rather, there are a number of policy instruments that can influence the size and nature of the response to avoidance and evasion, ranging from enforcement agency activities to how strongly rules and regulations are drafted. The same type of cost-benefit calculation applies to the choice of these instruments, implying that the behavioral response elasticity is itself a policy instrument, which should be chosen optimally.

An important challenge for the future is to add more empirical content to the theoretical models of the behavior of taxpayers and tax authorities. This is analogous to the crucial role for traditional tax theory of empirical research into the structure of individuals' preferences. Although accurate data are often difficult to obtain by their nature, new approaches such as controlled field experiments and analysis of changes in tax administration hold promise.

In some cases, administrative difficulties and widespread avoidance and evasion are caused by the inability of compromise-seeking legislators to agree on a well-defined law. Combining the analysis of public choice mechanisms that produce tax systems with the type of normative analysis can lead to a more complete understanding of the reality of taxation (Slemrod, Yitzhaki, 2001). The classic distinction between avoidance and evasion is due to Oliver Wendell Holmes, who wrote;

When the law draws a line, a case is on one side of it or on the other, and if it is legally on the safe side, it is not even worse that a party has taken full advantage of what the law allows. A World History of Tax Revolts: An Encyclopedia of Tax Rebellions, Revolts, and Insurrections from Antiquity to the Present. Does the use of general anti-avoidance rules to combat tax avoidance violate the principles of the rule of law?”.