One of the exciting things about metaethics is the way it is a crossroads for many other areas of philosophy. Rather, it addresses questions about the status of the opinions we form when we answer such questions.

BACKGROUND

This book is about meta-ethics, a sub-discipline of the philosophical study of ethics, and addresses second-order questions about ethics.1 This is what emerges when one thinks critically and carefully about the nature of one's own ethical views. Question 1: Which of the following is a metaethical question: (i) Is war ever morally legitimate? ii) What does it mean for something to be morally legitimate? iii).

FOUR KEY ISSUES

The third set of questions is where philosophical ethics comes into contact with the philosophy of language. That is, we will come to understand several different concepts derived from metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of language and philosophy of mind and use them to explain some of the main theoretical views found in metaethics.

FOUR MAIN THEORIES

Perhaps this is because ethical thought and discourse rests on a fundamental flaw: we often think we know things are right/wrong, good/bad, virtuous/vicious, but we are wrong (as Thrasymachus argued). If this is true, then perhaps there is an empirical method for resolving moral disagreements, or perhaps ethical knowledge is always relative to a particular culture or moral community.

CONCLUSION

CHAPTER SUMMARY

STUDY QUESTIONS

FURTHER RESOURCES

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS OF UNDERSTANDING

Expressivists think that when a statement is ethical in its content, the mental state is interestingly different from the kinds of beliefs about reality that we usually express with our statements. If those scribbles were made with the intention of conveying something (either a feeling or a thought) they may be expressive, but if they were merely the result of an accident, they would not express a state of mind.

WORKS CITED

NOTE

Questions in epistemology about the possibility of ethical knowledge and the nature of ethical disagreement. Questions in the philosophy of language about the meaning and expressive role of ethical words and sentences.

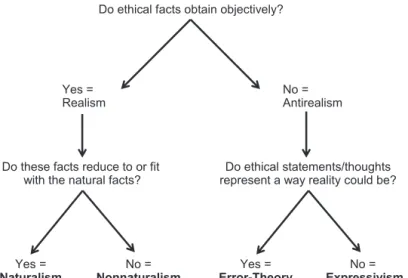

QUES TIONS ABOUT ETHICS AND METAPHYSICS

In metaethics, the central question is whether ethical facts are reducible to another kind of fact. Similarly, some may think that ethical facts depend on the reactions of particular people.

QUESTIONS ABOUT ETHICS AND EPISTEMOLOGY

As we will see in what follows, one's opinion about whether ethical facts exist depends very much on what one thinks they are. Importantly, there are competing views of what these facts are like and how exactly they are objective, but all of these views count as realist views because they conceive of ethical facts as being 'out there' as part of the reality to be discovered, and not merely as the reality that needs to be discovered. product or shadow of our subjective or intersubjective responses.1 Antirealism can then be understood as the rejection of realism.

QUESTIONS ABOUT ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE

In contrast, one prominent way to develop an anti-realist view in metaethics is by arguing that ethical sentences are simply not in the business of representing reality. First, to make sense of the view, we need an understanding of what is meant by "express." In a clear sense, everyone must agree that ethical sentences can be used to express something other than beliefs about reality.

QUESTIONS ABOUT ETHICS AND PHILOSOPHY OF MIND

Turning to the second question above, about the justification of actions, a common view is that a justifying reason for an agent acting in a particular way is a consideration that counts in favor of the agent acting in that way. A classic statement and defense of the human belief-desire account of the psychology of motivation.].

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS OF UNDERSTAN DING

A book-length defense of the possibility of moral knowledge, addressing many of the reasons for skepticism.

NOTES

Proponents of the view are usually motivated by the thought that there is an objective fact of the matter about many ethical issues, and ethical ways of thinking and inquiry about these facts differ significantly from the empirical ways of thinking and inquiry that we use to know about the natural world. Typically, an ethical non-naturalist will argue that, although empirical evidence can feed into ethical deliberation, the fundamental facts about what is good/bad, right/wrong, virtuous/evil are not empirically knowable facts: ethical facts are their own kind facts. which we must discover (when we can) in the particular way characteristic of ethical thought and deliberation.

A MORE PRECISE CHARACTERIZATION

For example, we can say that natural facts are facts that (iii) figure in or are governed by the laws of nature, (iv) have causal powers, or (v) reduce to physical facts. QU1: Which of the following putative facts are not plausible candidates for natural facts: (i) facts about the physical laws of the universe, (ii) facts about who is biologically related to you, (iii) facts about who has good karma, (iv) facts about what someone wants, (v) facts about consciousness, (vi) facts about mathematics.

THE CASE FOR NONNATURALISM

Here, many philosophers think that there are logical and mathematical facts, but they also think that these facts are not features of the natural world, but rather more abstract facts that structure both the real world and any other possible world. Similarly, non-naturalists in metaethics think that ethical facts are an autonomous realm of facts, although failure to meet criteria (i) and (iii) is also sometimes used to characterize this autonomy.

Hume’s Law

Moorean arguments

The fact that there is any debate at all about whether the analysis of some ethical property M in terms of some natural property N suggests that the question remains. This calls for explanation: why philosophers have not been able to analyze goodness (or justice or virtue) in terms of some natural property.

A further argument: deliberative indispensability

However, we should ask: why does finding the best explanation for what we observe give us a reason to believe in the reality of something. So this is why we are justified in believing in the entities/facts that figure in the best explanation of what we observe.

ARGUMENTS AGAINST NONNATURALISM

For example, Kant famously argued that, in terms of practical reasoning about what to do, we must assume that we are free to choose what we do. He also argued, however, that in terms of theoretical reasoning about what is the case, we must assume that every event is determined by previous events in a way that seems to preclude the freedom to choose what we do.

Challenge from a naturalistic worldview

However, if we go so far as to admit the existence of non-natural facts about reasons, one might think there is no further metaphysical objection to the recognition of non-natural ethical facts. Importantly, this explanation would not appeal to one's being good to detect mind-independent ethical facts.

Objection from epistemology

But the point is that someone who urges us to recognize the reality of some domain of non-natural facts faces the challenge of explaining how we can come to know such facts. First, some try to develop a positive epistemology to explain how we come to know non-natural facts.

Argument from supervenience

But to make this answer work, we need to actually show how to reason from scratch to the existence of unnatural ethical facts. Similarly, if we thought of our ethical statements as expressions of attitudes toward descriptive facts rather than their descriptions of ethical facts (as expressivists do), we would be able to develop a different explanation of why supervenience seems true. : these ethical attitudes one has towards the non-ethical reality should not be arbitrary. The expressivist account of supervenience will be explained more in chapter 3.) So the main issue here is whether nonnaturalists can give a convincing explanation of why ethics seems to prevail over unethics, or at least explain the appearance that there is something important that they explain in this regard.

Challenge from the practicality of morality

As long as we think that morality sometimes provides reasons for people to act in particular ways, since non-naturalists think that morality has to do with unnatural facts, it seems that they owe us an explanation of how such unnatural facts relate to our concerns. . It says that ethical facts and properties are indeed part of reality, which makes it a realist view.

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Resistance to the view comes from the naturalistic worldview, criticism of the epistemology of non-naturalism, an argument from the supervision of the ethical over the non-ethical, and challenges to the non-naturalist's ability to understand the practical application of morality. explain. 6 Why is it challenging for the non-scientist to explain the oversight of the ethical on the non-ethical?

ARGUMENTS IN FAVOR OF EXPRESSIVISM

Hume’s Law and open-question intuitions + naturalistic worldview

Argument from motivational internalism + Humean theory of motivation

Recall that a liability of non-naturalistic views in metaethics is that they have no easy explanation of the way in which the ethical status of action seems to depend intimately on the non-ethical facts of the situation. The ethical seems to predominate over the non-ethical: expressivists argue that the best explanation for this is that ethical thoughts are desire-like responses to how we accept the non-ethical facts, not beliefs in some separate realm of non-natural facts not.

VERSIONS AND OBJECTIONS

As far as that goes, though, the unnaturalist might try to steal a leaf from the expressivist's playbook. So this response on the part of the non-naturalists would open them up to a metaphysical challenge, but they would think that this challenge could be met.

Emotivism

And to say that something is right or good is not to describe it as having a specific quality, but rather to express a positive emotion about it—like cheering it on. To understand why many philosophers were dissatisfied with emotivism, it is helpful to delve a little into the history surrounding the development of Ayer's metaethical view.

Disagreement and prescriptivism

But Hare thought it was pretty clear that the missionary and cannibals did not agree in their use of 'stuff'. Because of this, he thought that their disagreement could not be about the fact that being brave and collecting many scalps has the quality of being good. but rather must be a difference of opinion in attitude and prescription. Therefore, we can say that the cannibals prefer people to be brave and collect scalps, and that they use 'stuff' to express this preference.

Blackburn and Gibbard on taking ethics seriously

There are two ways in which this idea has been used by expressivists to develop a version of the view that rejects Ayer's claim that moral philosophy is mostly empty. One of the main ideas in this was that in making ethical statements we are not simply expressing a feeling, but rather our commitment to systems of norms or general rules.

Truth-aptness and quasi-realism

He argued that the difficulty lies not in the expressivist's view of ethical terms, but rather in the general assumption that philosophers make about "true," "believes," "fact," and related terms. By adopting minimalism about “truth” and “belief” and “fact” (which are admittedly controversial views in themselves), it seems that expressivists can avoid the concerns generated by our mini-dialogues above.

Frege–Geach

It does not seem that the emotional "meanings" of simple sentences can be the content that these sentences contribute to the more complex conditional sentence. However, I want to close this section by suggesting that the validity of the conclusion is not the core problem.

Motivational internalism

7 What is the difference between expressionism and the subjectivist view that ethical statements are about what their author likes and dislikes. In metaethics, the central idea is to claim that basic ethical propositions are literally false, as well as that ethical discourse should be interpreted according to the model of a convenient fiction.

MACKIE’S ARGUMENTS FOR ERROR THEORY

But they would argue that ethical discourse does not even pretend to be about objective ethical values or facts, but rather is an expression of our commitment to our own values. Like many other metaethicists, Mackie assumes that ethical value (if it were to exist) would necessarily have to be separated from, but monitor, the natural features of an action.

OBJECTIONS AND REPLIES

Error theorists hold that ethical statements are intended to be about facts that are intrinsically motivational for those who know them and objectively descriptive for all of us. However, as long as the reasoning power of ethical facts depended on people's desires, worries, and concerns, we would not have to say that there was "doing" somehow contained in the facts themselves.

VERSIONS OF FICTIONALISM

PY 4: Consider the statement "The sun rises in the morning." What is the difference between the meaning of fictionalism and the fictionalism of speech in relation to this statement. Contains an important section on error theory, including an appendix discussing features of Mackie's arguments for error theory.]. ed.), International Encyclopedia of Ethics.

NEO-ARISTOTELIAN NATURALISM

His idea was that much of the debate about what it means to be good (period) is misguided, just as there would be to be a debate about what it means to be great (period). But Geach thought it pointless to ask what it means for something to be (simply) good.

RELATIVISM AS A FORM OF NATURALISM

Perhaps, to return for a moment to the non-subjectivist forms, the facts about what is ethically right/wrong and good. But when someone makes a sincere value judgment about what is (just) good, this must be implicitly understood as relative to one's own values.

A POSTERIORI NATURALISM

The basic idea is that we need an a posteriori survey of the world rather than an a priori analysis of concepts to determine what natural terms like "water" refer to. If this is correct, and we assume that "good" is also a natural term, then determining the nature of goodness (like determining the nature of water) would require a subsequent investigation of the causal chain between our use of the term and the property to which it refers.

A PRIORI NETWORK NATURALISM

Objects have the property of being orange if they appear to have the property of orange to normal observers under standard conditions. Objects have the property of being yellow if they appear to have the property of yellow to normal observers under standard conditions.

FU RTHER RESOURCES

Network analyzes offer an alternative model for an a priori conceptual analysis of ethical terms than that assumed by Moore and his critics. 7 Which is an example of a moral conceit; Would they support a net work analysis of ethical terms.

ANSWERS TO QUESTIONS OF UNDERSTANDING

QU6: To understand the statement of sentence (i), we need to know which direction defines the front and back. To understand what sentence (ii) is saying, we need to know when it counts as "today" in terms of which "yesterday" is the previous day; we also need to know where the "here" is for what is being said.

WORKS CITE D

2 It is a controversial issue in metaphysics how exactly to understand such 'natures'. The concept is related to, but more limited than, the idea of an essence. It is important to note that the form of relativism discussed above is the descriptive kind.

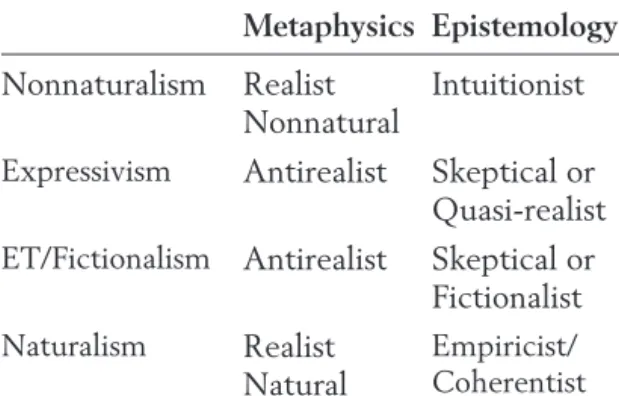

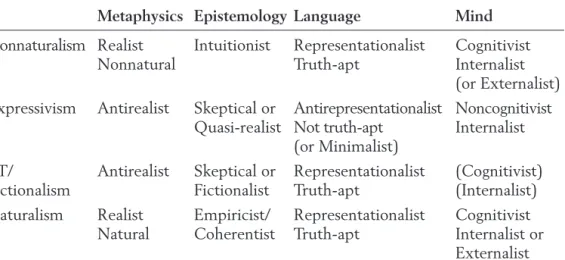

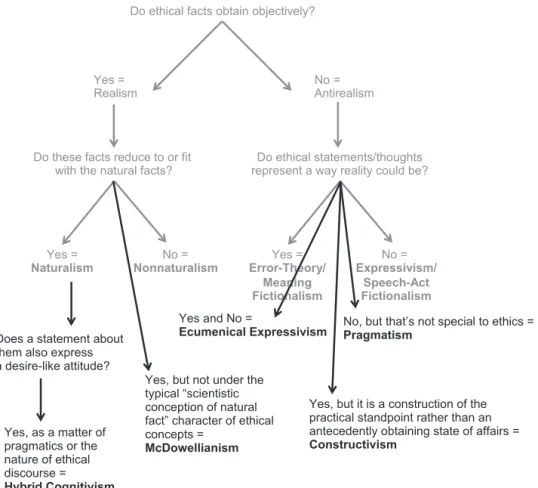

THE FOUR MAIN AREAS

The purpose of this chapter is to develop this chart to put you in a position to think carefully about which of these views you find most attractive, weighing the various costs and benefits of each theory. This means that deciding which metaethical theory you find most appealing will often be a matter of weighing a theory's theoretical benefits in metaphysics, epistemology, philosophy of language, and philosophy of mind against its theoretical costs in these areas. , and then compare. the result of competing theories.

Metaphysics

Epistemology

That is, if ethical facts are thought to be sui generis non-natural facts, the anti-realist may be skeptical that they can be known at all (perhaps because he is skeptical that there is such a thing as the capacity for moral intuition). Or similarly, if ethical facts are complex natural facts involving something like the instantiation of a homeostatic cluster of properties or the unique fulfillment of a node in a complex network of interrelated concepts, the anti-realist may be skeptical that they can be known at all. .

Philosophy of language

Philosophy of mind

Perhaps the best response to the error theorist's criticism of non-natural facts as "queer" (because they are intrinsically motivating) would be to argue that they are not intrinsically motivating after all. You can e.g. claim that they are the kind of facts that just usually motivate (good) people who recognize them.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

3 Assuming that one's main commitment in this area is to follow a naturalistic worldview, what are some of the routes one might take to arrive at a full metaethical theory. Assuming that one's strongest commitment in this area is motivational internalism, what are some of the routes one might take to arrive at a full metaethical theory.

BELIEFS OR DESIRES—WHY NOT A BIT OF BOTH?

All these ideas have a knock-on effect on the way we think about the scheme of metaethical theories and the dialectical situation we face as we sort through that scheme in search of the theory with the best ratio of theoretical benefits to cost.

McDowell

This rejection of the human psychology of motivation gives way to the suggestion that there is a certain knowledge that one simply cannot have without also being (at least partially) motivated in certain ways. But he does so without succumbing to the disadvantages that expressivism seems to suffer from making sense of the semantics of ethical language and the possibility of genuine ethical knowledge.

Ecumenical expressivism

However, they are ecumenical expressivists because they also think that part of the account of the meaning of ethical sentences will also advertise being conventional means of expressing cognitive states associated with conative states in the right way.2. That is, a simple version of ecumenical expressivism says that the meaning of the sentence is a matter of its expressing a disapproval of things insofar as they have some natural property, calling it F, and a belief that stealing is F.

Hybrid cognitivism

The basic idea would be to argue that although ethical sentences are literally about natural facts, using them to make a statement implies that the speaker has a desire-like attitude. To evaluate them yourself, you will want to consider whether they integrate the desire-like element associated with ethical discourse in a credible way.

ETHICAL FACTS—WHY DO THEY HAVE TO BE

More specifically, to count as engaging in the practice of genuine ethical discourse, we might think that someone must have the desire-like states necessary to account for the close connection between ethical judgment and motivation. So, in this kind of view, it is not an implication of a particular speech act that ensures the presence of a desire-like state, but rather it is part of what makes one's speech part of the language game of ethics: one does' t count as making an ethical statement unless one has the relevant wish-like state.

OUT THERE”?

As natural science positions, these theories are also committed to successfully solving the challenge of explaining which natural facts are ethical facts. From this point of view, there are ethical facts, but they are not completely "out there".

Response-dependence

First, metaethicists often distinguish between sentimentalism and rationalism as ways of developing versions of response-dependent views depending on the kinds of responses thought to be relevant to constituting ethical facts. Then you can say that what it is for something to be red is just that it must be such that an ideal observer would think it was red.

Constructivism

In this way, constructivists hope to argue that you do not regard some things as more or less valuable unless you adhere to certain ethical facts. To have reasons to act, there must be actors who take the practical stance and try to decide how to act.

PRAGMATISM

Yes, but it is a construction of a practical attitude and not a previously acquired state = constructivism. Constructivism in metaethics argues that ethical facts are not objective, in the sense that they are "out there" to be discovered, but rather are constructions of a practical attitude.

ANSWERS TO QU ESTIONS OF UNDERSTANDING

And it seems that all the same metaphysical, epistemological, linguistic, and psychological questions that we have explored about ethical thought and discourse could also be asked about such epistemological thought and discourse. We will see that many (though not all) of the arguments for and against these traditional theories can be transformed into arguments for and against similar theories of so-called universal normativity.

FROM METAETHICS TO METANORMATIVE THEORY

Then we will consider one specific domain of normativity that is not ethics: epistemology. We will explore some of the theoretical options and associated costs and benefits to give you an idea of how a similar debate might take place in relation to a specific non-ethical but still normative domain.

Nonnaturalism

If anything, it establishes non-naturalism about normative facts that apply to everyone (and extends to ethical facts because of their centrality to general normativity). The very intelligibility of this position makes the supervenience argument somewhat more difficult to apply to normativity considered universally.

Expressivism

Many philosophers will think that the situation is exactly the same regarding the normativity with which all things are treated. Arguments against expressivism in the ethical case extend to the case of universal normativity.

Error theory/fictionalism

These seem to be just as powerful concerns in the case of overarching normativity as in the ethical case. These are both positions that someone initially inclined toward error theory might take about all-things-considered normativity.

Naturalism

These are perfectly natural facts, and so facts about reasons of this kind can be perfectly natural. The other kind of naturalistic view about all things considered normativity that I want to mention is based not on facts about people's particular desires, concerns, and concerns, but on facts about human nature.

FROM METAETHICS TO METAEPISTEMOLOGY

That is, we can wonder about the status of claims about beliefs being justified and about people knowing things. We can ask about the epistemology of epistemology: when we know that someone knows something, how do we know it.

Metaepistemological realism

In this case, that is, we can ask about the metaphysics of knowledge and justification: are these objective properties "out there" in reality; and if so, what is their nature. We can ask about the meaning of epistemic statements: are these representations of reality or expressions of attitude or something else.

Metaepistemological antirealism

Indeed, the ethical expressivists were one of the first places where epistemic expressivism developed. That is, an epistemic expressivist might reject contextualism in favor of the view that "S knows that p" is a means of expressing a commitment to some set of evidential norms.

STUDY Q UESTIONS

As a partial overview of the theoretical traditions considered earlier in the book and as part of the overview of some of the initial theoretical possibilities in metanormative theory, we have considered how each of non-naturalism, expressivism, error theory/fictionalism and naturalism would seem when transposed to all-things-considered normativity. 5 What are some of the factual conditions that must apply for someone to know something.

FURTHER RESOURCES

ANSWERS T O QUESTIONS OF UNDERSTANDING

WORKS CIT ED

A way of developing the ideal observer's opinions about ethical truth, where the observer's ethical beliefs are important. A way of developing the ideal observer's opinions about ethical truth, where the observer's moral feelings are important.