Identifying predictors of attitudes towards local onshore wind development with reference to an English case study. Currently, the UK is heavily dependent on fossil fuels (mainly coal and natural gas) to meet the majority of the country's electricity demand (around 74%). Because while it is true that overall support for onshore wind and other renewable energy technologies exists in principle, specific projects often encounter opposition from members of the communities designated to host such projects (e.g. .

Such resistance is problematic as it often leads to delays in receiving building permits for developers, but also means that many projects (and thus valuable renewable generation capacity) never see the light of day (see Toke, 2005), contributing to achieving the UK's fair but ambitious renewable energy targets is becoming increasingly difficult. Leyden, 1995); (b) responsible for all the local resistance that tends to accompany onshore wind development (e.g. Wolsink and (c) responsible for the "social gap" that exists between the high levels of general support and comparative difficulties with to obtain planning permission (Bell et al. ., 2005.) Within this paper we use multiple regression analysis to establish the predictors of specific attitudes towards proposed onshore wind development in Sheffield, England.

Background to the study

We hoped that this research would help us identify (and better understand) the caveats that host communities place in their acceptance of local wind development. Importantly, we report on the attitudes and opinions of two different groups of respondents; one group that lives close to locations that have been found suitable for the development of onshore wind energy (target group) and a well-matched comparison group. The presence of the comparison group allowed us to examine the extent to which factors found to predict attitudes within the target group were specific to those living near the proposed development or likely to be shared by the general population as a whole.

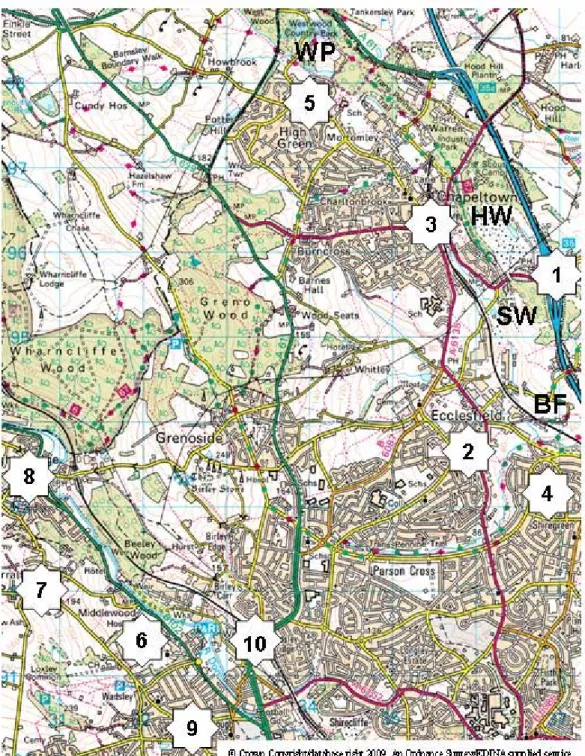

The four selected areas were later identified as privately owned land at Hesley Wood and Smithy Wood and Council owned land at Butterthwaite Farm and Westwood Country Park (see Figure 1). The announcement of plans for the development of these countries quickly began to stimulate debate within the local media and the local population, despite the fact that there were no concrete proposals. It was our aim to investigate how favorably or unfavorably communities in the area might be affected by developments, and a comparable but unaffected population was responding to notices.

Questionnaire Construction and Distribution

Five of these were adjacent to at least one of the identified sites (i.e. target villages), while the other five were in a suitable comparison location with the N.W. The comparison location was chosen on the basis that it was close enough to the identified sites for the sample to be interested in the proposals, but far enough away that respondents should not be directly affected by development at any of the four sites. The names and locations of the target and comparison towns and their relationship to the identified sites can be seen in Figure 1.

In the target towns, it was also determined that the households sampled must be within approximately 1.5 km (~ 1 mile) of at least one of the four identified sites. The authors considered that respondents should have answered at least three quarters of the items listed in the questionnaire (ie ≥ 90 of a potential 120 items). Importantly, this final sample contained similar numbers of both target and comparison respondents (i.e. 417 and 392 respondents respectively) and each of the target and comparison towns sampled was well represented (i.e.

Results

The first step in the analysis was to find out whether members of the target group showed signs of what could be perceived as NIMBYism. It is possible that this difference reflects a self-selection bias on the part of the target group. First, the effect of respondents' general attitudes towards wind development in the UK was calculated.

Thus, in both groups a large (and more or less equivalent) proportion of the variance in specific attitudes could be attributed to respondents' general attitudes towards onshore wind development. All three items were found to account for a similar amount of the variance and showed positive relationships with specific attitudes. The Section 3 analysis (Table 5) revealed that very few of the potential concerns/hazards were retained as unique predictors of specific attitudes.

Discussion

The distal nature of the sites identified meant that, for these respondents, development was likely to be considered in relatively 'general' terms. That said, we would echo the caveats that advise against assuming that the objection is motivated simply by a poor understanding of the issue at hand (ie a lack of knowledge). Of course, in order to implement such a policy, there is a requirement that developers be both appreciative of the specific concerns held by a community and deemed credible enough for their information to be accommodated. 2005) suggest that the key to achieving both of these goals is the involvement of local people in the planning process.

As such, the remaining findings will be discussed with reference to this ideal. This is because analysis of the relationships each of these items had in common with specific attitudes revealed that it was respondents who had more favorable attitudes towards local development who were most likely to find them attractive. As such, those who were more opposed to development were unlikely to view the economic benefits as particularly attractive.

In both groups, those who believed that development was likely to spoil the landscape and lower housing prices were more likely to be negatively inclined towards development in the identified locations and vice versa. The finding that fear of landscape devastation persisted in both groups is perhaps not surprising given the fact that many observers believe that the emergence of wind turbines is the main driver of local opposition (e.g. However, we also believe that within the context of this case study, conservation of this element reflected specific elements of the development context; not only was there no large-scale wind development in the Sheffield area at the time of distribution, but the relatively suburban nature of the identified sites meant that any development would affect the visual amenity of large numbers of people.

It is possible that without the benefit of a comparison group, the retention of concern over house prices within the target group may have been interpreted as evidence of NIMBYism. We suspect that the retention of this concern reflected not only a fear of change itself, but also a more general fear of the unknown resulting from the complete lack of hard details accompanying Sheffield City Council's announcements. The results of the analysis of Section 4 (trust) showed that, for the target group, trust in Sheffield City Council was a positive predictor of attitudes.

The results from the Section B (demographic) analysis show that while demographic factors appear to have little influence on attitudes within the comparison group; belief in anthropogenic climate change and home ownership among target group members were retained as predictors.

Conclusions

Indeed, when controlling for general attitude, very few of the items retained as predictors of specific attitude could be meaningfully interpreted as evidence of such concerns. Perhaps the only point approaching such a classification was the persistence of the threat of falling house prices within the target group; however, the retention of this point in the comparison group suggests that such concerns are not unique to those living near potential onshore wind turbine developments. Advances in offshore turbine technology should gradually relieve some of the pressure on onshore locations (although one should not assume that offshore development is immune to locally motivated opposition, see Devine-Wright, in press; Haggett, 2008); However, the UK government sees the significant expansion of both onshore and offshore capacity as key to achieving their legally binding renewable energy targets (DTI, 2007).

It should be noted that Sheffield City Council did not intend to personally develop renewable installations at any of the identified sites, but rather to offer the sites to suitable private developers. It should be remembered that the comparison respondents, although not living directly next to any of the identified localities, were still residents of the north of Sheffield and may have had an association with one or more of the target towns and/or identified locations. Social representations of intermittency and the shaping of public support for wind energy in the UK.

Silvercat Publications, San Diego, CA. Wind Energy Landscapes: Society and Technology in the California Desert. Social amplification of risk in participation: two case studies, in: Pidgeon, N., Kasperson, RE, Slovic, P. Eds.), The Social Amplification of Risk. Harnessing community energies: explaining and evaluating community-based localism in UK renewable energy policy.

Locations of four identified areas and 10 target and comparison sites selected for questionnaire distribution (scale: 1:50,000). 1 Assessed respondents' familiarity with proposals, level of interest in projects and initial response to announcements. Hierarchical regression analysis of the items of Section 1; dependent variable: the specific relationship that controls the general relationship.

Hierarchical regression analysis of the items from Section 2; dependent variable: specific attitude, controlling for general attitude. Hierarchical regression analysis of the items from Chapter 3; dependent variable: specific attitude, controlling for general attitude. Hierarchical regression analysis of the items from Chapter 4; dependent variable: specific attitude, controlling for general attitude.