or the slave levies carried out by Augustus in the context of the Pannonian revolt 7/6 CE and the Varusschlacht 9/10 CE, see Suet. However, examination of the epigraphical record has revealed nearly 500 inscriptions attesting to freedmen in the company of Roman Imperial soldiers of the principate (27 BC–284 AD).4 Slaves are attested much less frequently (n=57 ). Instead, as this article argues, the epigraphic and legal sources suggest that many of the soldiers' slaves remained in bondage until their master's death, after which they were freed by testamentary release.

This would mean that the liberti had actually been living as slaves throughout the memorial soldier's lifetime, a fact obscured in the epigraphic record. Three strands of evidence converge to suggest that testamentary manumission was a common route to freedom for many of the liberties attested in the soldiers' inscriptions.

Documentary Evidence for Testamentary Manumission by Soldiers

So far little-used evidence suggests that many of the freedmen in our record very likely obtained their freedom only after the death of their master, by testamentary surrender. In this case, the slave would be statuliber until he was freed from a certain number of days of work, see e.g. Paul (5 ad Sab.) Dig. In many documents from the eastern half of the Roman Empire, especially in the Egyptian papyri, the influence of Greek legal instruments is palpable.

Somewhat different is the perception we get from grave-epography, where freedmen appear to be more often involved in the construction of the monument, see M. 36 Unless heirs are instituted, liberti cannot preside over their patron's funeral, see Ulp. 106, believed to be a pay record of legionaries, on a papyrus dated 81 AD, where some of the soldiers stood.

Vafrius Tiro, centurion of the legion XXII Primigenia, on 23 March during the twelfth consulship of Emperor Domitian Augustus Germanicus (86 CE), at the age of thirty. Yet the inscription provides a rare illustration of the principle I am putting forward in this article, which is that slaves of soldiers remained in many cases in bondage until freed by wills. As such, they were stripped of the right to transfer their estate to whomever they wished.

As scholars have generally observed, Silvanus' will largely follows the strict rules of the traditional Roman testamentum per aes et libram, compare J.

The Legal Sources

As in the case of Iros/Eros, discussed above, Cronio's surrender is conditional on the performance of a service to his former master, although here it is not about commemoration but matters of accounting. 49 Antonius Silvanus decrees that Cronio render an account of the lord's estates, all or part of which appears to have been under his control, and deliver them to Silvanus's heir or procurator. Such accounting clauses appear routinely in Roman wills, as the discussions of testamentary delivery by Roman jurists in the Digest amply attest.50 The important point to note is that here we have yet another case of the enslavement of a soldier's slave who lasts until death. of the master, undermining Wierschowski's claim that they were freed "rather quickly" after being purchased.51 Moreover, although he remained a slave until Silvanus's death, Cronio was clearly involved in the management of his master's business interests , an activity that Wierschowski would no doubt have preferred to attribute to a freedom.52. The first is testamentum militis, the soldier's testament, dealt with in his title of the Digest (29.1).

Originally a temporary concession granted by Caesar to his soldiers,53 the testamentum militis was formally established by Titus (r. 79–81 CE) and took its mature form in the second century CE.54 It was available to all the armed forces of Rome. whether legionary or auxiliary.55 The central privilege of the soldier's will consisted in libera testamenti factio, freedom from obligation to fulfill all the complicated formal requirements imposed on a civilian will. The emperors were eager to show their benevolence to the body of men whose loyalty was so important to them.56 The form of the document was entirely in their hands. This traditional right of paternal control extended to any property given or acquired by family members.

The complicated provisions of the civil will, including the required qualifications for witnesses, are discussed Gai. Under praetorian law, a will sealed with the seals of seven witnesses was sufficient for the praetor to grant bonorum possessio to the person named in it as heir, but until the reign of Antoninus Pius it did not protect such a beneficiary from challenges for inheritance with intestate through sui heredes of the testator, compare Gai. The 2nd century jurist Maecianus still regarded the father as the ultimate owner of the peculium castrense, while the Severan jurists for the first time regarded the son as the owner, see B.

That they did so regularly is clear from the numerous references to testamentary manumission that we find throughout the sections on the soldier's will in the Digest (29.1) and the Codex Iustiniani (6.21).64.

Discussion of Funerary and Votive Inscriptions

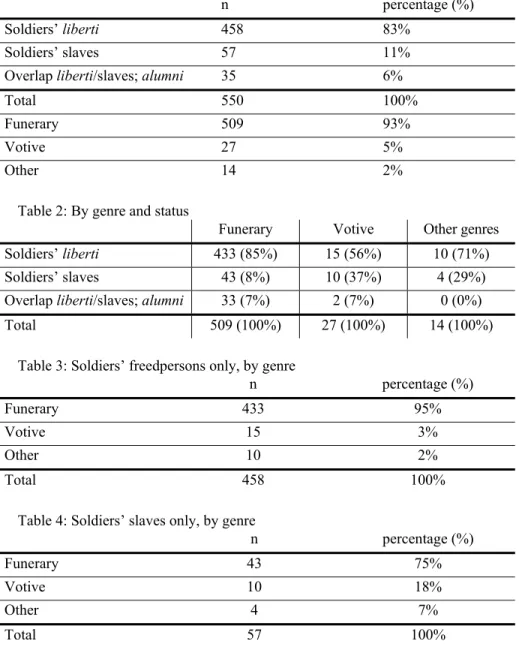

The privileges attached to the peculium castrense, as we can see, further reduced potential obstacles for citizen soldiers to make a valid will. These legal texts highlight how easy it was for Roman soldiers, whether or not they were Roman citizens, to make a valid will and include the manumit of slaves, at least from the reign of Titus (79–81 CE) onwards. The essential difference between these genres of inscriptions is that votive inscriptions were generally commissioned by a living master or patron, while epitaphs were placed in the context or at least in anticipation of the master's or patron's death. .

As the data show, we are more likely to encounter slaves in inscriptions where the master still lived, that is, especially in votive inscriptions. Focusing our attention on epitaphs, where the master usually passed away when the stone was erected, we see that the share of slaves is much smaller (8%), while that of the liberti is all the greater (85%). Unlike with votive inscriptions, there is no case of a slave himself erecting a stone for the master.67 The slaves who do appear in the epitaphs are all either by their master (31) or by fellow slaves (3). commemorate. ).

The higher ratio of freedom to slaves in soldier epitaphs compared to votive inscriptions fits well with my argument that soldier slaves were often freed after their master's death in accordance with a will, especially in light of the documentary and legal evidence presented above. . The purpose here is not to offer any strong quantification of the phenomenon, but simply to point it out as a factor that contributes significantly to the appearance of so much freedom in soldiers' inscriptions. While testamentary handwriting obviously cannot be at play in the approximately one hundred inscriptions in which militant patrons commemorate dead freedmen, there is at least a fair chance that it underlies some of the inscriptions that use the obscure formula (ish) testament

In the same way, texts that speak of liberti heredes may hide a testamentary manuscript, although it is usually impossible to determine when these individuals were freed, either before or after their master's death.

Conclusion

But at the same time we must be careful not to overstate our case. Yet we must bear in mind that none of the explanations can do justice to the full range of mechanisms and motivations at play. We are thus justified in considering a similar reversal of fortune for such individuals as Hermas, the libertus discussed at the beginning of section 2.

As the words ex textamento (sic! l. 5) reveal, his former master Capito, an auxiliary soldier, had apparently left behind a will containing a condition for the placement of the epitaph. A testamentary manuscript may well have included its final dispositions, although it was not recorded epigraphically. Analogously, one can certainly wonder whether testamentary delivery underlies the presence of a significant number of freedmen in civil epitaphs.70 However, given the much stricter legal restrictions governing civil wills, it seems reasonable to assume that testamentary surrender would have occurred less frequently outside the military community.

The evidence shows that the wealthy, well-educated strata of the Roman population easily overcame legal barriers and made large bequests, as Champlin pointed out. technical details related to the composition of such a document, which results in a lower rate of probate and thus indirectly a lower rate of probate. 72. 56: "In Rome there is (..) little evidence for testing below a fairly high threshold, that of relatively successful businessmen, civil servants, professional persons and landowners." The testators in the famous Testamentum Dasumii (FIRA III 48 = CIL VI 10229) and Testamentum Lingonis (FIRA III 49 = CIL XIII 5708 = ILS 8379) and most other civil wills with testamentary manumission were clearly above this line. This appendix provides a list of the 550 Latin, Greek, and Latin-Greek bilingual inscriptions used in this study that record slaves and freedmen in the company of Roman imperial soldiers (late 1st century BC to late 3rd century AD . 74 Abbreviations follow those in F.

Nova otkrića iz rimskog razdoblja na području Varaždinskih Toplica (= . Novija otkrića rimskih ostataka na području Varaždinskih Toplica), Zagreb 2015;.

101 = IGLS 13.1.9172

8762 = ILS 2594

10854 = ILS 2601

14934 = ILS 9164

2454 = ILS 2060

2532 = ILS 2093

2634 = ILS 2074

2963 = ILS 8382

3191 = ILS 2205

3413 = ILS 8203

3580 = ILS 2641

32873 = CIL X 6575

1603 = ILS 2235

3392 = ILS 2872

3442 = ILS 2898

3498 = ILS 2877

3523 = ILS 2834

17 = CIL III 179* = CIL III 297*

88 = ILS 2829

3007 = ILS 2542

1041 = ILS 2531

7031 = ILS 2500

IMS 2.152

2447 = ILS 2075

TAM 2.3.987 (?)