Centro de Ciências da Saúde

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde

AGREGAÇÃO FAMILIAR E RESULTADOS MATERNOS E PERINATAIS DA PRÉ-ECLÂMPSIA SEVERA EM POPULAÇÃO DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE

Patricia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles Bezerra

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

Centro de Ciências da Saúde

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde

AGREGAÇÃO FAMILIAR E RESULTADOS MATERNOS E PERINATAIS DA PRÉ-ECLÂMPSIA SEVERA EM POPULAÇÃO DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE

Patricia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles Bezerra

Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, para obtenção do título de Doutor em Ciências da Saúde.

ORIENTADORA: Profa. Dra. Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo

CO-ORIENTADORA: Profa. Dra. Selma Maria Bezerra Jerônimo

Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte. UFRN/Biblioteca Setorial do CCS

B574a

Bezerra, Patrícia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles.

Agregação familiar e resultados maternos e perinatais da pré-eclâmpsia severa em população do Rio Grande do Norte / Patrícia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles Bezerra.___ Natal-RN, 2007.

111f.

Orientadora: Profª. Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo. Co-orientador: Profª Selma Maria Bezerra Jerônimo.

Tese (Doutorado em Ciências da Saúde) - Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Ciências da Saúde.Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciências da Saúde.

1.Obstetrícia - Tese. 2. Pré-eclâmpsia -Tese. 3. Eclâmpsia - Tese. 4.Síndrome HELLP –Tese. I. Araújo, Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de. II. Jerônimo, Selma Maria Bezerra. III. Título.

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE

CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE

PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CIÊNCIAS DA SAÚDE

Coordenador do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde

Patricia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles Bezerra

AGREGAÇÃO FAMILIAR E RESULTADOS MATERNOS E PERINATAIS DA PRÉ-ECLÂMPSIA SEVERA EM POPULAÇÃO DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE

Presidente da Banca: Profa. Dra. Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo

BANCA EXAMINADORA:

Profa. Dra. Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo

Prof. Dr. Francisco Mauad Filho (UNAERP)

Profa. Dra. Maria Amélia de Rolim Rangel (UFPB)

Profa. Dra. Selma Maria Bezerra Jerônimo (UFRN)

“...Sorri,

Quando tudo terminar

Quando nada mais restar

Do teu sonho encantador, sorri...”

Dedicatória

Aos meus pais, Fernando e Graziela, pelos ensinamentos profissionais e de vida, que, sempre, me proporcionaram.

Ao meu esposo, Aluisio Augusto, pelos momentos de ausência e que, com compreensão, me deu estímulos para a realização deste sonho.

Aos meus filhos, Aluisio Neto, Juliana e Victor, essência da minha vida, mola precursora de todas as minhas realizações.

Agradecimentos especiais

À Profa. Dra. Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo, minha

orientadora e amiga, a quem tanto estimo e admiro, pelo exemplo de amizade, sapiência e dedicação ao ensino. Eternamente serei grata.

À Profa. Dra. Selma Maria Bezerra Jerônimo, minha

Agradecimentos

Às pacientes que fizeram parte desta pesquisa e que, desta forma, contribuíram para a melhoria dos nossos conhecimentos acerca desta patologia, minha sincera gratidão.

À Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco, representada pelo seu diretor, Prof. Dr. Kleber de Melo Morais, pela amizade e apoio na realização desta pesquisa.

Ao Programa de Pós-Graduação do Centro de Ciências da Saúde da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, representado pelo seu coordenador, Prof. Dr. Aldo da Cunha Medeiros, pelo incentivo e dedicação a este programa.

À Profa. Dra. Maria Hebe de Oliveira Nóbrega, pela valiosa ajuda que me foi dada com os seus ensinamentos e na execução deste trabalho.

Às funcionárias da Enfermaria de Gestação de Alto Risco e UCI da Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco, em especial, a enfermeira Maria de Lourdes Costa da Silva, pela presteza na parceria da coleta dos exames e dedicação profissional.

Às bolsistas do Laboratório de Imunogenética do Departamento de Bioquímica da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, hoje médicas, Dra. Janaína Aleixo Alves e Dra. Ana Kalline Jerônimo Silva, pela valiosa participação na coleta e elaboração do banco de dados.

Aos colegas pós-graduandos, Edailna Maria de Melo Dantas, Flávio Venício Marinho Pereira e Marcos Dias Leão, pelo espírito de colaboração e agradável convívio nos momentos de estudo.

Aos médicos residentes da Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco, pela colaboração e compreensão na realização deste trabalho.

Sumário

Dedicatória...vi

Agradecimentos especiais...vii

Resumo...xi

1. INTRODUÇÃO...1

1.1 Objetivo geral...5

1.2 Objetivos específicos...5

2. REVISÃO DA LITERATURA...6

3. ANEXAÇÃO DOS ARTIGOS...14

Artigo 1...15

Artigo 2...39

Artigo 3...59

4. COMENTÁRIOS, CRÍTICAS E CONCLUSÕES...80

5. ANEXOS...87

6. REFERÊNCIAS ...94

Resumo

Objetivo: Determinar a agregação familiar na pré-eclâmpsia severa em população brasileira do Rio Grande do Norte e caracterizar os resultados maternos e perinatais desta população.

Métodos: Estudo de caso controle, no qual foram arroladas 412 pacientes internadas na Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco (MEJC). Dessas, 264 pacientes normotensas, grupo controle, e 148 com pré-eclâmpsia severa, grupo dos casos. Os casos foram compostos por eclâmpsia (n=47), síndrome HELLP (n=85) e por ambas, eclâmpsia e síndrome HELLP (n=16). O diagnóstico, destas doenças, foram baseados nos critérios adotados pelo National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working (2000). Foi realizado inquérito familiar quanto à agregação familiar, sendo questionadas informações a respeito de antecedentes de hipertensão crônica, pré-eclâmpsia, eclâmpsia e síndrome HELLP. Análise estatística foi realizada para avaliar associações e correlações entre variáveis, bem como comparação de médias ou medianas, adotando-se um nível de significância de 5%. O Odds-Ratio foi calculado para estimar o risco da pré-eclâmpsia severa nas famílias.

materna foi baixa 0,4% e a mortalidade perinatal alta de 223 por 1000 nascidos vivos. O risco de uma mulher, cuja mãe teve hipertensão ou pré-eclâmpsia, vir a ter pré-eclâmpsia é, respectivamente, 2,5 e 3,5 vezes. Esse risco aumenta para cinco vezes, quando a irmã tem antecedente de hipertensão e seis vezes quando, tanto a mãe quanto a irmã têm antecedentes de pré-eclâmpsia.

Conclusões: Este estudo confirma a agregação familiar da pré-eclâmpsia em população brasileira. O risco aumentado para doenças cardiovasculares e hipertensão crônica nestas mulheres, indica a necessidade de seguimento das pacientes que desenvolvem pré-eclâmpsia.

1. INTRODUÇÃO

Pré-eclâmpsia é uma doença hipertensiva, multissistêmica, de causa ainda desconhecida, peculiar à gravidez humana e específica da segunda metade da gestação (SIBAI et al, 2005). É considerada um problema de saúde pública mundial, devido a sua alta incidência, 2% a 7% em mulheres nulíparas saudáveis (SIBAI et al, 2005) e drástica repercussão na morbimortalidade materna e perinatal, principalmente, em países em desenvolvimento (SIBAI et al, 1995; ONRUST et al, 1999; KIM et al, 2001).

Embora a causa da pré-eclâmpsia, ainda, esteja por ser determinada, pesquisas recentes sugerem a somatória de fatores genéticos, imunológicos e ambientais (SIBAI et al, 2005; REDMAN & SARGENT, 2005; MUTTER & KARUMANCHI, 2007; SARGENT et al, 2007).

como uma enfermidade complexa, onde os fatores genéticos, que contribuem para a sua gênese, têm herança poligênica e multifatorial.

De fundamental importância no acompanhamento de mulheres com pré-eclâmpsia, é o reconhecimento de determinados fatores de risco, decorrentes de aspectos imunológicos (SIBAI et al, 2005).

Observações clínicas permitem afirmar que há uma maior incidência em primigestas, particularmente, nos dois extremos da vida reprodutiva (CARITIS et al, 1998; DEKKER & SIBAI, 2001; BASSO et al, 2001; HNAT et al, 2002) e em multíparas com mudança de parceiro (TUBBERGEN et al, 1999; SAFTLAS et al, 2003). O risco aumenta naquelas pacientes usuárias de métodos anticoncepcionais de barreira, uma vez que torna limitada a exposição ao esperma com o mesmo parceiro antes da concepção (EINARSSON et al, 2003; DEKKER & ROBILLARD, 2005). Situações de hiperplacentação, que ocorre em gestação molar e gemelar, sugere o papel da placenta como agente iniciador da resposta imunológica (CARITIS et al, 1998; SIBAI et al, 2000; TRELOAR et al, 2001).

BLOOD PRESSURE IN PREGNANCY (2000). É definido, como pré-eclâmpsia, a ocorrência de pressão arterial sistólica maior ou igual a 140 mmHg e pressão arterial diastólica maior ou igual a 90 mmHg na presença de proteinúria.

Na história natural da pré-eclâmpsia, observa-se evolução para eclâmpsia, presença de convulsão na gravidez, excluído outro fator etiológico, em menos de 1% das mulheres em países desenvolvidos, em contraste com taxas de 15%, observadas nos países em desenvolvimento (WALKER, 2000; COPPAGE & SIBAI, 2005; SIBAI et al, 2005). SIBAI (1990) refere que a eclâmpsia determina uma elevada incidência de morbidade materna por determinar insuficiência renal aguda, edema agudo de pulmão e insuficiência cárdiorrespiratória. Em 12% dos casos de pré-eclâmpsia severa desencadeia-se a síndrome HELLP (anemia hemolítica, elevação das transaminadesencadeia-ses e plaquetopenia) (MARTIN et al, 1991; REPORT OF THE NATIONAL HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE EDUCATION PROGRAM WORKING GROUP ON HIGH BLOOD PRESSURE IN PREGNANCY, 2000; VIGIL-DE GRACIA, 2001) entidade clínica grave, determinante de coagulação intravascular disseminada e hematoma hepático subcapsular (BARTON & SIBAI, 1992; SIBAI et al, 1993; ARAÚJO et al, 2006).

Em avaliações epidemiológicas, têm sido observado que, dentre as causas determinantes de prognóstico perinatal desfavorável, prevalece o descolamento de placenta e a insuficiência placentária, incorrendo em elevados índices de prematuridade (SIBAI et al, 1993; MAGPIE TRIAL COLLABORATIVE GROUP, 2004).

As gestações, complicadas por pré-eclâmpsia, poderão identificar mulheres com risco de desenvolver em doença vascular em longo prazo e permitir, portanto, a oportunidade de mudanças de hábitos de vida, minimizando os fatores de risco para esta doença (SATTAR & GREER, 2002; ROBERTS & GAMMILL, 2005; BAUMWELL & KARUMANCHI, 2007).

A ocorrência de pré-eclâmpsia, em gestação subseqüente é de aproximadamente, 20% (O’BRIEN & BARTON, 2005) e síndrome HELLP recorrente varia de 2% a 19% (CHAMES et al, 2003; VAN PAMPUS & AARNOUDSE, 2005).

1.1.1 Objetivo Geral

• Avaliar a agregação familiar em pacientes com pré-eclâmpsia severa (eclâmpsia e/ou síndrome HELLP), em população do Rio Grande do Norte.

1.1.2 Objetivos Específicos

2. REVISÃO DA LITERATURA

A pré-eclâmpsia tem sido reconhecida como uma doença da gravidez desde a antiguidade e o primeiro relato, acerca de caso de eclâmpsia, foi registrado em Kahum, papiro egípcio há 3.000 anos (STEVENS, 1975; CHESLEY, 1984). Em 1619, Varandaeus usou, pela primeira vez, o termo “eclâmpsia”, baseado nos escotomas que antecedem as crises convulsivas em mulheres grávidas (RIPPMANN, 1971).

A associação entre hemólise, trombocitopenia e disfunção hepática foi descrita na literatura há mais de 50 anos. Em 1954, PRITCHARD et al descreveram 03 mulheres com esta associação, das quais apenas uma sobreviveu. Em 1973, MC KAY relatou 04 casos dessa síndrome, incluindo duas com ruptura hepática e uma morte materna. PRITCHARD (1978) apresentou 95 casos de eclâmpsia, com 29% de trombocitopenia. Entretanto, o termo síndrome HELLP (Hemolysis, Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets) foi primeiramente descrito, por WEINSTEIN, em 1982.

Nos últimos anos, têm sido realizados diversos estudos, com o propósito de determinar a etiologia da pré-eclâmpsia, Contudo, ainda não é possível explicar, com exatidão, a condição primária que predispõe o início da cascata fisiopatológica, desencadeada nesta patologia.

SUTHERLAND et al, 1981; ARNGRÍMSSON et al, 1990; CINCOTTA & BRENNECKE, 1998; MOGREN et al, 1999), o exato padrão de herança ainda é desconhecido. Diante da complexidade da pré-eclâmpsia nos níveis hemodinâmico, bioquímico e imunológico, não fica claro que um simples gene materno, em combinação com um genótipo fetal, revele sua herança genética. Acredita-se em um fator poligênico, com interferência ambiental e imunológica, atuando na gênese da pré-eclâmpsia.

O caráter familiar da pré-eclâmpsia/eclâmpsia foi observado desde 1800, embora só tenha sido bem documentado por CHESLEY et al em 1968, após análise de 27 publicações relativas a pacientes e familiares acometidas por esta patologia. A primeira publicação, revisada por CHESLEY et al (1968), foi a de ELLIOT (1873), na qual ele citava a repetição da doença em uma mesma família, quando registrou um caso fatal de eclâmpsia em mulher, cuja mãe havia morrido com o mesmo quadro, em sua quinta gestação. Cada uma, das suas quatro filhas, teve eclâmpsia e três morreram em conseqüência desta doença.

Contribuindo com a hipótese da predisposição genética materna, através de um possível gene recessivo, SUTHERLAND et al (1981) encontraram maior incidência em mães (14%) de mulheres que tiveram pré-eclâmpsia que em sogras (4%). CHESLEY E COOPER (1986) encontraram similar resultado, favorecendo a herança materna em relação à fetal e à paterna.

tiveram esta enfermidade e 10% de casos entre suas sobrinhas, sugerindo uma contribuição genética materna na patogênese da pré-eclâmpsia.

Outros estudos sugerem a contribuição paterna, através do componente fetal. LISTON & KILPATRICK (1991) levantaram a possibilidade de homozigose para um mesmo gene recessivo, tanto na mãe quanto no feto, como causa de pré-eclâmpsia. Freqüência aumentada de pré-eclâmpsia é associada com gestação gemelar e, se o antígeno fetal tiver alguma influência na doença, nesta situação, a mãe encontra-se submetida à dose extra de carga genética fetal, principalmente, nas gestações gemelares homozigóticas.

Em 1998, CINCOTTA & BRENNECKE demonstraram que o risco de pré-eclâmpsia é quatro vezes maior em primigrávidas com história familiar de eclâmpsia.

Estudo, realizado por TUBBERGEN et al (1999), demonstrou que a mudança de parceiro aumenta o risco de pré-eclâmpsia em gestações subseqüentes e DEKKER & SIBAI (2001) afirmam que há diminuição do risco, quando a mudança de parceiro ocorre após uma gestação com pré-eclâmpsia.

Influência paterna foi confirmada em um grande trial realizado em Utah, no qual ESPLIN et al (2001), analisando homens e mulheres descendentes de gestações complicadas por pré-eclâmpsia, tiveram maior ocorrência de crianças provenientes de gestações com pré-eclâmpsia.

PAWITAN et al (2004) observaram, também, a herança materna e fetal e CARR et al (2005) demonstraram uma significante associação de pré-eclâmpsia entre irmãs, reforçando a importância dos fatores genéticos na gênese, desta patologia. Outros estudos, ainda, apontam a interação de gene materno e fetal, determinando uma herança multigênica (COOPER & LISTON, 1979; LISTON & KILPARICK, 1991).

Avaliações de dados de registros de nascimentos da Noruega, realizados por SKJAERVEN et al (2005), permitiram identificar componentes maternos e paternos predispondo a pré-eclâmpsia, sendo o componente materno mais forte que o paterno.

Para a abordagem do estudo genético de enfermidades complexas, como a pré-eclâmpsia, se faz necessária a utilização de duas metodologias: estudo de associação, tratando de identificar genes candidatos implicados na gênese da patologia ou estudo de ligamento genético, identificando regiões cromossômicas em famílias que apresentam esta patologia.

condição. Genes, envolvidos com as citocinas inflamatórias e com a resposta imune, como o fator de necrose tumoral (TNF-α) e interleucina-1 (IL-1), têm sido estudado. CHEN et al (1996) encontraram associação entre o TNF-α e pré-eclâmpsia, enquanto LACHMEIJER et al (2001), em uma extensa pesquisa, não encontraram associação entre polimorfismo na região do TNF-α, com pré-eclâmpsia ou síndrome HELLP. Resultados semelhantes, em relação a IL-1, foram encontrados por HEFLER et al (2001), constatando não haver associação entre esses genes e pré-eclâmpsia.

Embora haja uma evidência da associação de pré-eclâmpsia com trombofilia, ainda não está, claramente, elucidado no âmbito molecular (LACHMEIJER et al, 2002). Estudos realizados descreveram a associação de mutação no gene da Metilenetetrahidrofolato redutase (MTHFR) (SOHDA et al, 1997; KUPFERMINC et al, 1999; VEFRING et al, 2004), embora outros estudos não tenham confirmado estes achados (LIVINGSTON et al, 2001; LACHMEIJER et al, 2001). A deficiência do fator V Leiden tem sido associada ao aumento do risco de pré-eclâmpsia (KUPFERMINC et al, 1999; MORGAN & WARD, 1999; LIN & AUGUST, 2005), não confirmado por outros autores (BOZZO et al, 2001; LIVINGSTON et al, 2001; DE MAAT et al, 2004). Outro gene candidato é o gene da enzima óxido nítrico sintetase endotelial (NOS3). ARNGRÍMSSON et al (1997) detectaram um possível locus de susceptibilidade

à pré-eclâmpsia e à eclâmpsia na região do cromossomo 7q36, o qual codifica os genes da enzima óxido nítrico sintetase endotelial.

do cordão umbilical e dos seus parceiros, a fim de estudarem sete genes (Angiotensina (AGT), Receptores de Angiotensina 1 e 2 (AGTR1 e AGTR2), TNFα, NOS3, MTHFR e Fator V Leiden) implicados na gênese da

pré-eclâmpsia. Os autores concluíram que estes genes não estão associados a risco, aumentados de pré-eclâmpsia.

Os trabalhos de pesquisa continuam sendo realizados, inclusive com varreduras de genoma (genomewide linkage), sendo detectados alguns loci de

cromossomos com maior susceptibilidade, mesmo assim, ainda não foi isolado um gene específico para a pré-eclâmpsia. É possível que um polimorfismo genético e fatores ambientais estejam implicados na gênese desta patologia, como visto nos trabalhos desde a década passada.

O primeiro trabalho, com varredura de genoma para a pré-eclâmpsia, foi realizado na Escóssia, por HAYWARD et al (1992), em 35 famílias, no qual os autores encontraram uma maior susceptibilidade para genes nos cromossomos 1, 3 e 9. O segundo, australiano, publicado por HARRISON et al (1997), em 15 famílias identificaram, que o braço longo do cromossomo 4 possui uma região candidata para um locus de susceptibilidade à

pré-eclâmpsia e à eclampsia, com um LOD score de 2.91. Em 1999, GUO et al

realizaram estudos de varredura de genoma, usando marcadores para o cromossomo 7. Estes autores concluíram que há possibilidade de um locus de susceptibilidade para pré-eclâmpsia e eclâmpsia na região 7q36, com um LOD score de 3.53. Contudo, não há nenhuma evidência definitiva para suportar a

ARNGRÍMSSON et al (1999) avaliaram 343 mulheres, de 124 famílias islandesas e reportaram o primeiro locus de susceptibilidade à

pré-eclâmpsia/eclampsia, preenchendo os critérios para significância sobre o cromossomo 2p13 (LOD score de 4.77). MOSES et al (2000) chegaram a

propor que o cromossomo 2 poderia ser designado de “PREG1” (pré-eclâmpsia, eclâmpsia gene 1).

LAIVUORI et al (2003) realizaram varredura do genoma em uma população finlandesa de 63 mulheres, sendo analisadas 435 marcadores. Encontraram um ligamento significativo nas regiões cromossômicas 2p25 e 9p13.

LAASANEN et al (2003) analisaram uma população finlandesa de 115 mulheres normotensas, 133 mulheres com pré-eclâmpsia e 57 mulheres com colestase intra-hepática, utilizando marcadores microsatélites na região 2p13-p12, a fim de detectar um loci potencialmente associado com a pré-eclâmpsia.

Observaram uma relação mais significativa com um alelo comum para pré-eclâmpsia e colestase intra-hepática. Portanto, ficou evidenciado um locus de

risco, com o mesmo marcador encontrado por ARNGRÍMSSON et al (1999), mostrando uma área de grande interesse na genética da pré-eclâmpsia.

Sabemos, até esta data, que as regiões mais significativas, com relação às regiões cromossômicas, imbricadas na gênese da pré-eclâmpsia, se encontram nos cromossomos 2 e 4. Nestas regiões cromossômicas, identificadas até agora, estão depositadas todas as expectativas sobre os genes que elas podem conter.

Pelo acima exposto, fica claro que pesquisas, sobre os marcadores da síndrome hipertensiva da gestação, são estudos complexos e caros, já que o padrão de herança da pré-eclâmpsia não se enquadra em nenhuma explicação genética simples. Além dos fatores confundidores, envolvidos em desordens de genes únicos, como heterogeneidade genética e fenocópias, interações gene-gene e gene-gene-ambiente também devem ser consideradas.

3. ANEXAÇÃO DOS ARTIGOS

Artigo 1 Título: Family history of hypertension is a risk factor for development of eclampsia and HELLP syndrome in a Brazilian Population – Artigo enviado para publicação no BJOG : an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

Artigo 2 Título: Characteristics and treatment of hepatic rupture caused by HELLP syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006 Jul;195(1):129-33.

Artigo 1

Family history of hypertension is a risk factor for development of eclampsia and HELLP syndrome in a Brazilian Population

P.C.F.M. Bezerra,1,2 M.D. Leão,1 J. W. Queiroz,1M. H. N. Oliveira , MD, PhD1, S.M. B. Jerônimo, MD, PhD1,3; A. C. P. F. Araújo, MD, PhD1,2

Health Graduate Program1 and Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco2, Health Science Center, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil; Health Science Center; Department of Biochemistry3, Bioscience Center,

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil

Corresponding Author

Araujo, A C P F

Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco

CP 1624

Natal, RN, 59078-970, Brazil

Fax and Phone: 55-84-3215-3428

e-mail: crysaraujo@uol.com.br

headline: familial aggregation of hypertensive syndrome in pregnancy

Synopsis: Presence of family history of hypertensive disorders increases the

ABSTRACT

Objective: To determine the outcome and risk factors to develop severe preeclampsia in a Brazilian population.

Methods: A case-control study was conducted with a total of 412 subjects, 264 controls and 148 cases of severe preeclampsia.

Results: Epigastric pain was more frequently present in HELLP syndrome, whereas headache was present in eclampsia. Blurred vision, headache and epigastric pain were reported when both entities were present. Maternal mortality was 0.4% and perinatal mortality was 223 per 1,000 births in the case group. Previous history of hypertensive disorders was more frequently found in the case group. An increased risk of preeclampsia was observed in women whose mother or sister had a history of chronic hypertension or preeclampsia, respectively, 2.5 and 5.2 times. The risk was increased 6 times when a sister and mother had hypertension.

Conclusions: Family history of hypertensive disorders increases the risk of severe preeclampsia in a Brazilian population.

INTRODUCTION

Preeclampsia is a disease of unknown cause characterized by abnormal placentation, increased vascular resistance and platelet aggregation [1]. Gemelarity, systemic hypertension, previous history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and thrombophilias are risk factors to developing preeclampsia [2]. There is a great variability in the incidence of preeclampsia, varying from 1.5% in Sweden, to 3.8% in the United States [3], to 7.5% in Brazil [4]. Although impressive advances in maternal and perinatal care have led to reduction of mortality due to severe preeclampsia in developed countries, where mortality varies from 0.4 to 7 [5], the management has not still been optimal in underdeveloped countries where the maternal mortality.rate can surpass 25% [6], and the perinatal mortality can reach up to 30-40% [7].

Eclampsia and HELLP syndrome are the major complications of preeclampsia [5]. There is a strong tendency to repeat preeclampsia in successive pregnancies. Studies have shown that women who develop severe preeclampsia earlier into the pregnancy have an increased risk of cardiovascular disease later in life, in addition to further complications in subsequent gestations [8]. Children born of preeclampsia pregnancy can present with intrauterine growth restriction, resulting in long-term growth deficit [9].

paternal origin carried by the fetus [11,12]. The change in partner increases the risk of preeclampsia in subsequent pregnancies [13].

Studies on candidate genes as angiotensinogen, 1 and 2 angiotensin receptors, tumor necrosis factor , endothelial nitric oxide synthase, methylene tetrahydrofolate reductase and the Leiden variant of coagulation factor showed an association of these genes with severe preeclampsia [14]. A genome wide scan performed in Iceland detected a significant locus on 2p13 [15], which was confirmed by another study conducted in Australia and New Zeland [16]. These two studies were validated by fine mapping indicating the presence of a susceptibility gene on chromosome 2p11-12 and substantiated findings of a second locus on chromosome 2q23. These studies support the hypothesis that genetic factors might play a role in susceptibility to preeclampsia, although the genetic polymorphisms could vary among human populations.

METHODS

Study design

A case-control study was conducted between November 2001 and October 2004. Subjects with severe complications of preeclampsia, including eclampsia and HELLP syndrome and pregnant normotensive women, in Natal, Brazil, were enrolled. A total of 412 subjects were enrolled, 264 controls and 148 cases.

Cases and controls were enrolled from a population with similar ethnic and social-economic background, and they were matched by age, gestational age and parity. The control group was selected based on the absence of signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Cases were composed of eclampsia (n=47), HELLP syndrome (n=85) and eclampsia associated with HELLP syndrome (n=16).

Ethical considerations

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte Ethical Research Committee (Protocol 08/01) and the Brazilian National Ethical Research Committee (Protocol CONEP 4586). All subjects or their legal guarding gave formal consent.

Case definition

Preeclampsia was defined by the Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program [1]. Hypertension was considered as blood pressure of at least 140 mmHg (systolic) or at least 90 mmHg (diastolic) on at least two occasions and at least 4-6 h apart after the 20th week of gestation in

women known to be previously normotensive. Proteinuria was defined as a protein concentration of 300 mg/L or more (≥ 1 + on dipstick) in at least two

random urine samples taken at least 4-6 h apart [1].

Eclampsia was defined as presence of tonic-clonic seizures, with hypertension developing after the 20th week of pregnancy [1].

HELLP syndrome was defined as presence of hemolytic anemia, altered liver function with LDH greater than 600 IU/L, total billirubin greater than 1.2 mg/dl, elevated liver enzymes AST and ALT greater than 70 IU/L and platelets lower than 100.000/mm3 [7,17].

Treatment of Preeclampsia

or post-partum periods. Blood pressure was controlled with methyldopa or nifedipine. Supportive therapy with blood derivatives, diuretics and dialysis were used as needed. Patients with HELLP syndrome received a total dose of 30 mg of dexamethasone IV, 10 mg at 12 hours interval.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the software STATISTICA 6.1 Copyright Statsoft 1984-2003, Tulsa, OK 74104. USA. The sample size allowed to compare by two binomial proportions using a two-sided test with significance level of 5% and to detect a minimum variation percent of 50% with a power of 80% between cases and controls. Means and standard deviations of continuous data were calculated and analyzed using a test F (ANOVA One-Way).

RESULTS

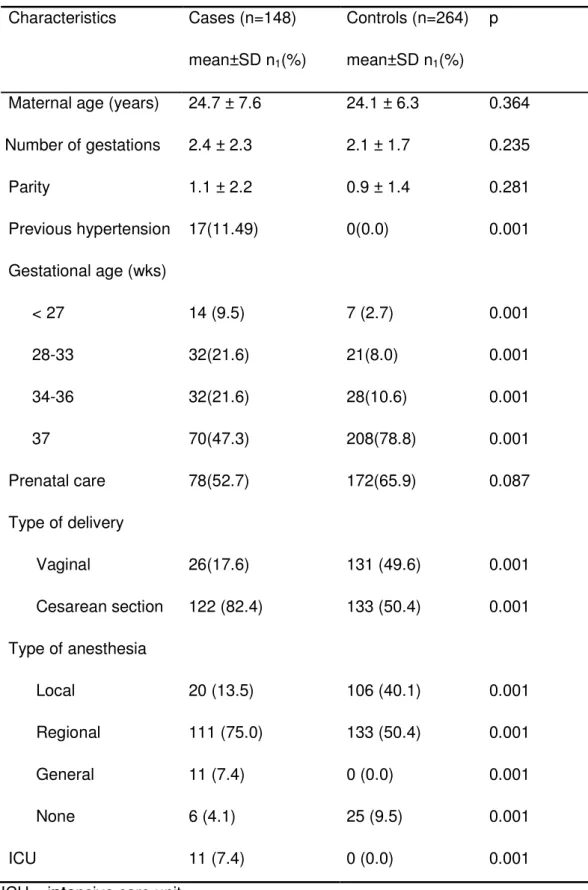

A group of 148 cases of severe preeclampsia and 264 controls were studied. The mean age for cases and controls were similar, respectively, 24.7 years (SE± 0.6) and 24.1 years (SE ± 0.4). No difference in the number of gestations and parity was found, 2.4 (SE ± 0.2) and 1.1 (SE ± 02) for the cases and 2.1 (SE ± 0.1) and 0.9 (SE ± 0.1) for the control group, respectively. The two groups were similar in age (p=0.364) and primiparity (p=0.281). Of significance was the history of systemic arterial hypertension (p=0.001), previous preeclampsia (p=0.001) and eclampsia (p=0.042) in the case group, as shown on table 1. The case group had a small frequency of prenatal care visits (52.7%) compared to controls (65.9%), although the difference was not significant (p=0.087). Cesarean section was used more frequently in the case group (p=0.001). Regional anesthesia was used for the majority of the cases, (Table 1).

bleeding episodes (50%) and acute renal insufficiency (25%), table 2. One of our patients (0.4%) with the diagnosis eclampsia complicated with HELLP syndrome died because of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

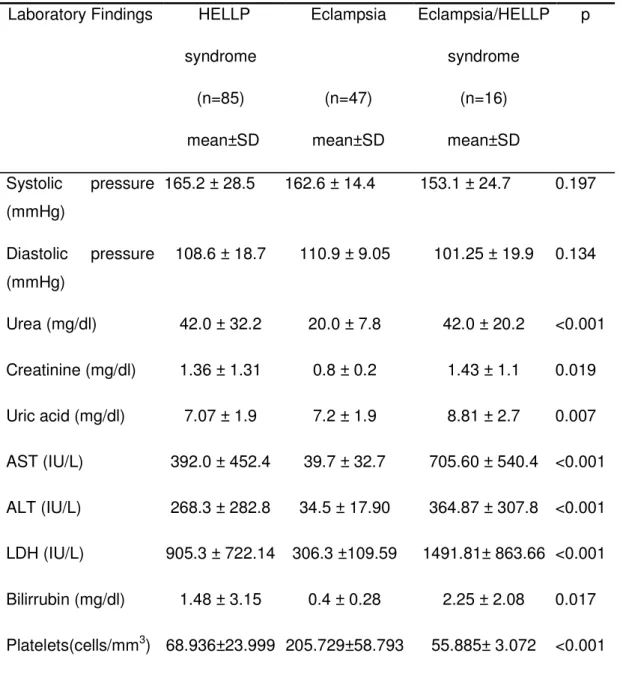

The mean arterial systolic (p=0.197) and diastolic (p=0.134) pressures showed no difference between eclampsia, HELLP syndrome and eclampsia complicated with HELLP syndrome. Patients with HELLP syndrome alone or complicated with eclampsia had a higher mean plasmatic urea (42 mg/dl). An increase in creatinine levels was also observed, respectively, 1.36 mg/dl and 1.43 mg/dl, for these two entities. Lower levels of platelets were seen in HELLP syndrome and eclampsia complicated with HELLP syndrome, respectively, 68,936/mm3 and 55,885/mm3, table 3.

The newborns from the case group had lower weight (p<0.001) and score APGAR at 5th minute lower than 7 (p<0.001). The newborn CAPURRO scores born of the case group were lower (36.8; SD ± 3.0; p<0.001). The perinatal mortality was higher in the case group (n=33), 223 per 1,000 births, whereas the control group presented a mortality of 19 per 1,000 (p< 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Preeclampsia is a severe illness with high maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality [5]. The prevalence of severe complications of preeclampsia in Brazil is high and particular in Natal, Brazil, where this study was conducted [4,19]. HELLP syndrome seems to be a risk factor for eclampsia [17,20]. Severe preeclampsia seems to occur more frequently in primiparous and younger women, as seen in this study population. There is evidence that the high risk of preeclampsia is related to the maternal first exposure to chorionic villi, specifically the trophoblast, which is of fetal origin. The protective effect of multiparity, however, can be lost when there is a change of partner [21].

Restrictions in the usage of regional anesthesia in HELLP syndrome has been argued, partly because of low platelet counts and the risk of epidural hemorrhage [1], although more recently epidural has been recommended in patients with HELLP syndrome. Regional anesthesia was used safely in our cases of HELLP syndrome and no complications were observed, in spite of the low platelet counts [7].

and chronic hypertension are risk factors for the development of HELLP syndrome and eclampsia [5]. Persistence of hypertension post-partum in the case of HELLP syndrome or eclampsia has increased the risk of cardiovascular complications later in life [5]. In this way it would be recommended that patients with a history of hypertensive disorders of pregnancy should be carefully monitored for cardiovascular disorders [5].

Renal insufficiency was a frequent complication of our case group, but none evolved with chronic renal insufficiency, which can be a common complication of HELLP syndrome [17]. The occurrence of placental abruption was seen more frequently found in HELLP syndrome and eclampsia, similar to previous reports [17,20].

In this study, the majority of the cases had a gestational age below 37 weeks. The majority of the newborn presented Apgar score less than 7 at 5th minute after birth and lower weight, similar to findings in other studies [22]. The maternal outcome in gestations complicated with eclampsia and HELLP syndrome has improved in most places, including in this study area, although the perinatal mortality has not and this could be due to the advance stages in which the mothers are admitted to tertiary care center and/or the poor adherence to prenatal care. In this awareness of the importance of close follow up of high risk gestations as severe preeclampsia should be raised to allow better monitoring and follow up throughout the gestational months.

preparation), higher than described for other populations. Studies have shown that there is a heritability component influencing the development of preeclampsia [23]. The presence of familial aggregation of preeclampsia has strengthened the hypothesis of a genetic susceptibility to developing preeclampsia [24]. In this study we found that women with HELLP syndrome and eclampsia had a significant family history of hypertension, considering mother and sisters status of systemic hypertension, preeclampsia or eclampsia, indicating familial clustering of hypertensive disorders in this population. The information on personal and family history was taken from the patient, and information was also collected by interviewing another family member, usually a first degree relative, from both cases and controls, in order to avoid bias of patient recall, likely to occur since a case of severe preeclampsia could remember better previous similar familial or personal medical histories. We found that presence of hypertension in a mother and in a sister increased 6 times the risk of a woman to develop severe preeclampsia [12,25]. This is consistent with findings in Sweden where maternal preeclampsia was associated with 70% excess risk of preeclampsia in daughters [10].

Table 1. Clinical and Obstetric characteristics of the study group

Characteristics Cases (n=148) mean±SD n1(%)

Controls (n=264) mean±SD n1(%)

p

Maternal age (years) 24.7 ± 7.6 24.1 ± 6.3 0.364 Number of gestations 2.4 ± 2.3 2.1 ± 1.7 0.235

Parity 1.1 ± 2.2 0.9 ± 1.4 0.281

Previous hypertension 17(11.49) 0(0.0) 0.001 Gestational age (wks)

< 27 14 (9.5) 7 (2.7) 0.001

28-33 32(21.6) 21(8.0) 0.001

34-36 32(21.6) 28(10.6) 0.001

37 70(47.3) 208(78.8) 0.001

Prenatal care 78(52.7) 172(65.9) 0.087

Type of delivery

Vaginal 26(17.6) 131 (49.6) 0.001

Cesarean section 122 (82.4) 133 (50.4) 0.001 Type of anesthesia

Local 20 (13.5) 106 (40.1) 0.001

Regional 111 (75.0) 133 (50.4) 0.001

General 11 (7.4) 0 (0.0) 0.001

None 6 (4.1) 25 (9.5) 0.001

ICU 11 (7.4) 0 (0.0) 0.001

Table 2. Clinical presentation of eclampsia and HELLP syndrome

Symptoms HELLP Syndrome

n=85 (%) Eclampsia n=47(%) Eclampsia/ HELLP Syndrome n= 16 (%)

Total

n=148 (%) Epigastric pain 54(63.5) 6(12.8) 7(43.8) 67(45.3) Headache 45 (52.9) 40(85.1) 7(43.8) 92(62.2) Dizziness 34(40.0) 36(76.6) 6(37.5) 76(51.4) Blurred vision 30 (35.3) 30(63.8) 8(50.0) 68(46.0) Vomiting 29 (34.1) 17 (36.2) 4 (25.0) 50 (33.8) Nausea 28(32.9) 5 (10.6) 3 (18.8) 36 (24.3)

Complications

Oliguria 29 (34.1) 1 (2.1) 4 (25.0) 34 (22.9) Bleeding 26 (30.6) 2 (4.3) 8 (50.0) 36 (24.3) Renal failure 12 (14.1) 0 (0.0) 4 (25.0) 16 (10.8) Abruptio

Placentae

12 (14.1) 2 (4.3) 1 (6.3) 15 (10.1)

IUGR* 4 (4.7) 2 (4.2) 1 (6.2) 7 (4.7) DIC** 3 (3.5) 0 (0.0) 4 (25.0) 7 (4.7) Coma 0 (0.0) 2 (4.3) 2 (12.5) 4 (2.7) Pulmonary

edema

1 (1.2) 0 (0.0) 2 (12.5) 3 (2.0)

*Intrauterine growth restriction

Table 3. Laboratory findings found for subjects with eclampsia and HELLP syndrome.

Laboratory Findings HELLP syndrome

(n=85) mean±SD

Eclampsia

(n=47) mean±SD

Eclampsia/HELLP syndrome

(n=16) mean±SD

p

Systolic pressure (mmHg)

165.2 ± 28.5 162.6 ± 14.4 153.1 ± 24.7 0.197

Diastolic pressure (mmHg)

108.6 ± 18.7 110.9 ± 9.05 101.25 ± 19.9 0.134

Table 4. Risk of severe preeclampsia taking into account maternal or sister history of hypertensive disorders.

Family relationship Cases n=148 (%)

Controls n=264 (%)

Odds Ratio (95% CI)

p

Maternal History

Chronic hypertension 58 (41.1) 56 (21.9) 2.5 (1.6 to 3.9) 0.001 Preeclampsia 11 (8.0) 6 (2.4) 3.5 (1.3 to 9.3) 0.011 Eclampsia 4 (2.9) 1 (0.4) 5.7 (0.9 to 36.7) 0.038 Sisters’ history

Table 5. Risk of eclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome taking into account maternal and sister history of hypertensive disorders

Family history Cases n=148 (%)

Controls n=264(%)

Odds Ratio 95% (CI )

p

Sisters with hypertension and mother normotensive

7(4.7) 6(2.3) 3.0 (1.0 to 9.1) <0.0001

Sisters and mother

with hypertension 13(8.8) 2(0.7) 6.3 ( 1.5 to 26.3) <0.0001 Sisters with PE* and

mother without PE* 23(15.5) 13(5.0) 4.0 (1.9 to 8.2) <0.0001 Sisters and mother

with PE* 1(0.7) 0(0.0) 2.1 (0.1 to 63.4) <0.0001 Sisters with E** and

mother without E** 9(6.1) 4(1.5) 4.2 (1.3 to 13.3) <0.0001 *PE = Preeclampsia

Acknowledgements

Reference List

1. Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000 Jul;183(1):S1-S22.

2. Sibai BM. The magpie trial. Lancet 2002 Oct 26;360(9342):1329-2.

3. Ventura SJ, Martin JA, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ, Park MM. Births: final data for 1998. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2000 Mar 28;48(3):1-100.

4. Gaio DS, Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Nucci LB, Matos MC, Branchtein L. Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: frequency and associated factors in a cohort of Brazilian women. Hypertens Pregnancy 2001;20(3):269-81. 5. Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2005 Feb

26;365(9461):785-99.

6. MacKay AP, Berg CJ, Atrash HK. Pregnancy-related mortality from preeclampsia and eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2001 Apr;97(4):533-8.

7. Magann EF, Martin JN, Jr. Twelve steps to optimal management of HELLP syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 1999 Sep;42(3):532-50.

8. O'Brien JM, Barton JR. Controversies with the diagnosis and management of HELLP syndrome. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005 Jun;48(2):460-77.

9. Grisaru-Granovsky S, Halevy T, Eidelman A, Elstein D, Samueloff A. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and the small for gestational age neonate: not a simple relationship. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2007 Apr;196(4):335.

11. Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Fraser A, Kerber R, Mineau G, Carrillo J, et al. Paternal and maternal components of the predisposition to preeclampsia. N Engl J Med 2001 Mar 22;344(12):867-72.

12. Skjaerven R, Vatten LJ, Wilcox AJ, Ronning T, Irgens LM, Lie RT. Recurrence of pre-eclampsia across generations: exploring fetal and maternal genetic components in a population based cohort. BMJ 2005 Oct 15;331(7521):877.

13. Tubbergen P, Lachmeijer AM, Althuisius SM, Vlak ME, van Geijn HP, Dekker GA. Change in paternity: a risk factor for preeclampsia in multiparous women?. J Reprod Immunol 1999 Nov;45(1):81-8.

14. Disentangling fetal and maternal susceptibility for pre-eclampsia: a British multicenter candidate-gene study. Am J Hum Genet 2005 Jul;77(1):127-31.

15. Arngrimsson R, Sigurard tS, Frigge ML, Bjarnad ttir RI, Jonsson T, Stefansson H, et al. A genome-wide scan reveals a maternal susceptibility locus for pre-eclampsia on chromosome 2p13. Hum Mol Genet 1999 Sep;8(9):1799-805.

16. Moses EK, Lade JA, Guo G, Wilton AN, Grehan M, Freed K, et al. A genome scan in families from Australia and New Zealand confirms the presence of a maternal susceptibility locus for pre-eclampsia, on chromosome 2. Am J Hum Genet 2000 Dec;67(6):1581-5.

17. Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, Salama M, Mercer BM, Friedman SA. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (HELLP syndrome). Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993 Oct;169(4):1000-6.

19. Araujo AC, Leao MD, Nobrega MH, Bezerra PF, Pereira FV, Dantas EM, et al. Characteristics and treatment of hepatic rupture caused by HELLP syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2006 Jul;195(1):129-33.

20. Vigil-De GP. Pregnancy complicated by pre-eclampsia-eclampsia with HELLP syndrome. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001 Jan;72(1):17-23.

21. Dekker G, Sibai B. Primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention of pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2001 Jan 20;357(9251):209-15.

22. Noraihan MN, Sharda P, Jammal AB. Report of 50 cases of eclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2005 Aug;31(4):302-9.

23. Salonen RH, Lichtenstein P, Lipworth L, Cnattingius S. Genetic effects on the liability of developing pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am J Med Genet 2000 Apr 10;91(4):256-60.

24. Carr DB, Epplein M, Johnson CO, Easterling TR, Critchlow CW. A sister's risk: family history as a predictor of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2005 Sep;193(3 Pt 2):965-72.

ARTIGO 2

Characteristics and Treatment of Liver Rupture due to HELLP Syndrome

Ana C.P.F. Araujo, M.D., PhD1, Marcos D. Leao, M.D.,2 Maria H. Nobrega, M.D., PhD1, Patricia F.M. Bezerra, M.D.,1,2 Flavio V.M. Pereira, M.D.2, Edailna M.D. Melo, M.D. 2 George D. Azevedo, M.D., PhD3, Selma M.B. Jeronimo, M.D., PhD1,4

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, 2Health Graduating Program, Health Sciences Center 3Department of Morphology, 4Department of Biochemistry, Bioscience Center, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil

Corresponding Author:

Selma M.B. Jeronimo

Department of Biochemistry, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte

CP 1624, Natal, RN, 59078-970, Brazil

Phone: 55-84-215-3428

Fax: 55-84-214-3428

Condensation

ABSTRACT

Objective: The purpose of this study was to review the management of hepatic rupture due to HELLP Syndrome, and to assess maternal and perinatal outcomes of these subjects.

Study Design: A retrospective study of confirmed HELLP syndrome cases complicated by hepatic rupture was conducted.

Results: Ten cases of hepatic rupture were identified. The median maternal age was 42.5±5.9 years (median ± SD), and the median gestational age at delivery was 35.5±4.9 weeks. The most frequent signs and symptoms of hepatic rupture were sudden onset of abdominal pain, acute anemia and hypotension. Laboratory findings included a low platelet count and increased hepatic enzymes. Surgical treatment was performed in 9 cases and one case was treated non-surgically. The maternal mortality was 10%, and the perinatal mortality was 80%.

Conclusion: A combination of surgical treatment with hepatic artery ligation and omental patching with supportive measures were effective in decreasing mortality in hepatic rupture due to HELLP syndrome in Rio Grande do Norte, Brazil.

Key words: Hepatic rupture, HELLP Syndrome, Preeclampsia, hepatic artery ligation

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous hepatic rupture is a rare, but life-threatening complication of preeclampsia, frequently associated with HELLP Syndrome, which is defined as hemolysis, elevation of hepatic enzymes and low platelet counts.1 During pregnancy, the incidence of spontaneous hepatic rupture is reported to be between 1 in 45,000 and 1 in 225,000 overall deliveries.1,2,3 The most common clinical signs of hepatic rupture are right upper quadrant or epigastric pain, severe right shoulder pain, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, and hypovolemic shock.4 The successful management of hepatic rupture has been shown to involve a combination of surgical intervention and aggressive supportive care. Several surgical approaches have considerably decreased the morbidity and mortality associated with this entity, 1 but there is still not an agreement upon the best approach to treat this severe complication of pregnancy.

Maternal mortality is high when hepatic rupture occurs, varying from 18 to 86% in different series reported. Death results largely from complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation, pulmonary edema, or acute renal insufficiency.5,6,7,8 The objective of this study was to review the management of hepatic rupture due to HELLP Syndrome and to assess the maternal and perinatal outcomes through a retrospective analysis of a large case series treated in a single medical center in Natal, Brazil between 1990-2002.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A review of 10 cases of pregnancy with spontaneous hepatic rupture due to HELLP syndrome treated at the maternity hospital of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte (Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco) in Natal, Brazil between 1990 and 2002 was performed. The University Hospital is a referral center that manages all complications of pregnancies for subjects without health insurance for the state of Rio Grande do Norte. HELLP syndrome was defined as a severe preeclampsia, with subjects having a platelet count <100,000/microliter, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) greater than 72 U/L, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) greater than 600 U/L.9 The characteristics of the cases are shown as the median plus or minus the standard deviation (SD).

Cases were studied retrospectively, with each patient chart reviewed. The Maternity Hospital admits approximately 7587 subjects yearly, of these 5346 are deliveries. The incidence of HELLP syndrome was calculated based on 64,156 admissions registered between 1990 and 2002. Charts of 635 of patients with preeclampsia were reviewed in a six month period. The incidence of HELLP syndrome was calculated for this reference center with confidence interval of 95%.

RESULTS

Ten cases of hepatic rupture due to HELLP syndrome were treated at the Maternal University hospital. An average of 1 case of hepatic rupture in 5346 deliveries was observed during the 12 years studied. The incidence of hepatic rupture was 0.015% for all cases and 3.1 % for subjects with complete HELLP syndrome. General characteristics of the hepatic rupture cases were as follows: median age of 42.5 years (SD 5.90), median parity of 4.5 (SD 5.48), and median gestational age at delivery of 35.5 weeks, (SD 4.8) .

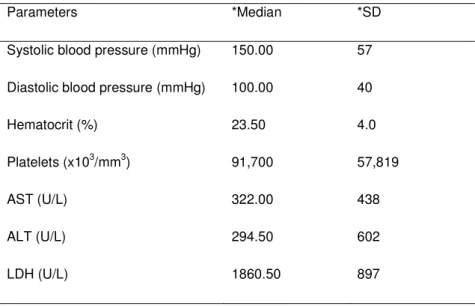

The major symptoms at admission were vaginal bleeding (8/10) and abdominal pain (7/10). The median laboratory values at diagnosis were a low hematocrit (23.5%, with SD 4.7), low platelet count (91 x 103/mm3, with SD 57,819), and elevated serum AST (322 with SD 438 U/L), ALT (294 with SD 602 U/L), and LDH (1,860 with SD 897 U/L) levels. The median systolic blood pressure was 150 mmHg (SD 57) and the median diastolic blood pressure was 100 mm Hg, (SD 40). Table 1 shows the major clinical and laboratory findings at observed at admission.

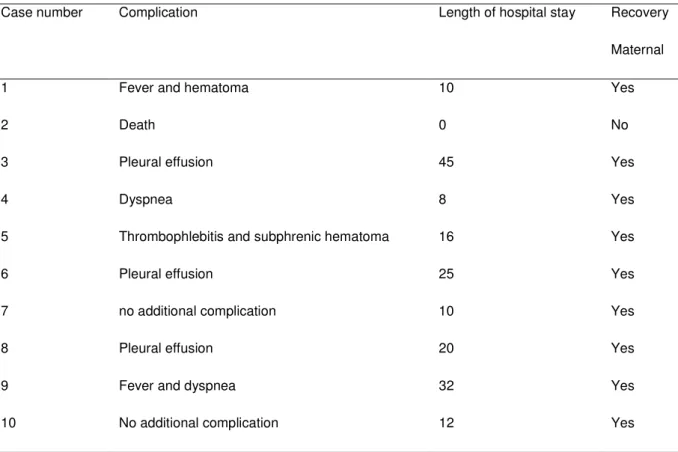

The grade of hepatic involvement varied from a minor capsular laceration to extensive parenchymal rupture. The majority of the hepatic lesions were found in the right lobe. One patient with a stable subphrenic hematoma was treated conservatively. Cases with minor capsular lacerations (n=3) underwent suture and omental patching. Patients who presented with non-friable and localized lesions (n=5) underwent hepatic artery ligation and cholecystectomy. One of these patients who presented with more extensive lesions had the hepatic parenchyma compressed with surgical towels prior to hepatic artery ligation. Cholecystectomies were performed to avoid gallbladder necrosis. One patient who was admitted in hypovolemic shock underwent immediate laparatomy. A large ruptured hepatic hematoma was observed in the right lobe. This patient died during the surgical procedure. Almost all subjects received support therapy with transfusion of blood products including plasma, cryoprecipitate, red blood packs and platelets. The one exception was a patient treated conservatively who also received albumin. Table 2 shows the demographics and types of treatment for cases in this series.

Case 1 (Table 2)

Case 2 (Table 2)

A 36 year-old woman (G3P2), gestational age 36 weeks, was admitted because of seizures. She presented initially with a blood pressure of 90/60 mmHg, a thready pulse, and uterine hypertonia. No fetal pulse was detected. A clinical diagnosis of placental abruption was made. The major laboratory findings at admission were a platelet count of 92.0 x 103/mm3, AST 1,861 U/L, LDH 1,514 U/L, and a hematocrit of 25%. Patient underwent a laparotomy and a stillbirth was delivered with signs of recent death. Extensive abdominal bleeding due to hepatic laceration was observed. The hepatic artery was ligated, followed by cholecystectomy and suture of the hepatic lesion. Post-surgical supportive therapy included plasma, cryoprecipitate, and red blood cell transfusions. Patient was monitored carefully by ultrasound. Her post-operative course was complicated by fever on day the subsequent post-operative days, but blood cultures were negative. According to serial ultrasound examinations a hepatic hematoma formed post-surgically, but spontaneously reabsorbed after two weeks, when patient was discharged.

Case 3 (Table 2)

Laboratory findings showed a platelet count of 80.0 x 103/mm3, AST 430 U/L, LDH 2,960 U/L and a hematocrit of 15%. A laparotomy revealed hemoperitoneum and a large hepatic laceration. The patient developed cardio pulmonary arrest during surgery, followed by death.

Spontaneous hepatic rupture is a rare and life threatening complication of pregnancy, that reportedly occurs in 1 out of every 45,000 to 225,000 deliveries.9 Hepatic rupture occurs in pregnancies complicated by preeclampsia, eclampsia, or HELLP syndrome.10 In our series, a higher incidence of hepatic rupture was seen. The majority of these cases did have not proper management of their preeclampsia. In addition, the Maternity Hospital is a reference center for major obstetrics complications, likely increasing the incidence of this condition.

A large case series composed of 141 cases of hepatic rupture was compiled from different studies.10 Of these cases, 58 indicated a platelet nadir, and 77.5% of these had platelet counts of less than 100,000.11 Our cases fulfilled the criteria complete HELLP syndrome. Hepatic rupture in our series occurred more often than not in multiparous women over age 40, In contrast, other studies have not reported age as a risk12, although some reports have claimed that multiparous older women are at a higher risk of developing intrahepatic hemorrhage than younger or primiparous women.13 One of our case occurred post-partum. Post-partum hepatic rupture has been reported in another series.14

hepatic artery ligation, embolization of the hepatic artery, to liver transplants. In our series, 50% of the cases underwent hepatic artery ligation. The shortcomings of this procedure and its association with maternal mortality have been discussed in other reports. Nonetheless, in our cases no complication of hepatic artery ligation were observed, and patients were discharged on the average 16 days after admission.

The mortality rate in hepatic rupture in pregnancy has decreased from 100 percent to 30 percent in the recent cases series.8,10 A substantial reduction in mortality has been attributed to the introduction of several procedures, including hepatic arterial embolization.10 In our series, 10 % mortality was observed, which is considerably lower than the reported mortality. Nonetheless perinatal child mortality in our series was high, similar to other reports.10

Non-surgical management of hepatic rupture has been considered in cases without coagulopathy.10 In our series, only one case of hepatic rupture was managed medically, without surgical intervention. This particular patient had a high surgical risk due to the anatomical location of the hepatic lesion, and she did not present with signs of active bleeding. We conclude that patients treated with supportive medical care alone should be carefully followed up, with adequate hemodynamic support and regular imaging.15, 16

surgical intervention with hepatic artery ligation was successful. This series illustrates that patients with hepatic rupture and HELLP syndrome should be treated by a multidisciplinary team of physicians and other health professionals in a setting where adequate supportive care is available to treat this life threatening condition.

Table 1. Hepatic rupture associated with HELLP syndrome: clinical and laboratory findings at admission

Parameters *Median *SD

Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) 150.00 57

Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) 100.00 40

Hematocrit (%) 23.50 4.0

Platelets (x103/mm3) 91,700 57,819

AST (U/L) 322.00 438

ALT (U/L) 294.50 602

Table 2. Demographics and treatment of hepatic rupture.

Case Age Parity Time of occurrence Treatment Blood products

1 36 2 36 wks pregnancy HA ligation and cholecystectomy cryoprecipitate, packed red

2 44 14 Puerperium (1st day) No procedure (dead at admission) No therapy

3 43 10 24 wks pregnancy Omentum patching Plasma, cryoprecipitate, pac

4 48 3 Puerperium (1st day) Surgical stitching Plasma, cryoprecipitate, pac

5 43 15 37 wks pregnancy HA ligation and omentum patching Plasma, cryoprecipitate, pac

6 42 5 34 wks pregnancy HA ligation and omentum patching Plasma, cryoprecipitate, alb

7 45 15 40 wks pregnancy Surgical stitching and omentum

patching

Plasma, cryoprecipitate

8 42 3 35 wks pregnancy HA ligation and omentum patching Plasma, cryoprecipitate, pla

9 38 4 38 wks pregnancy Clinical observation and monitoring Albumin

10 27 3 33 wks pregnancy HA ligation and cholecystectomy Plasma, cryoprecipitate

Table 3. Complications and maternal and neonatal outcomes in hepatic rupture

Recovery

Case number Complication Length of hospital stay

Maternal

1 Fever and hematoma 10 Yes

2 Death 0 No

3 Pleural effusion 45 Yes

4 Dyspnea 8 Yes

5 Thrombophlebitis and subphrenic hematoma 16 Yes

6 Pleural effusion 25 Yes

7 no additional complication 10 Yes

8 Pleural effusion 20 Yes

9 Fever and dyspnea 32 Yes

10 No additional complication 12 Yes

References

1. Barton JR, Sibai BM. Care of the pregnancy complicated by HELLP syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992;21:937-50.

2. . Smith LG, Moise HJ, Dildy GAIII, Carpenter RJ Jr. Spontaneous rupture of the hepatic during pregnancy: current therapy. Obstet Gynecol 1991;177:171-5.

3. Nelson DB, Dearmons V, Nelson MD. Spontaneous rupture of the hepatic during pregnancy: a case report. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurse 1989; 18:106-13.

4. Sibai BM. The HELLP syndrome (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets): much ado about nothing? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990 Feb;162(2):311-6.

5. Wicke C, Pereira PL, Neeser E, Flesch I, Rodegerdts EA, Becker HD. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma in HELLP syndrome: Evaluation of diagnostic and therapeutic options--a unicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190:106-12.

6. Gonzalez GD, Rubel HR, Giep NN, Bottsforf JE Jr. Spontaneous hepatic rupture in pregnancy: management with hepatic artery ligation. South Med J 1984;77:242-5.

8. Bis KA, Waxman B. Rupture of the hepatic associated with pregnancy: a review of the literature and report of 2 cases. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1976;31:763-73.

9. Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, Salama M, Mercer BM, Friedman SA. Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated hepatic enzymes and low platelets (HELLP syndrome). Am J Obstet Gynecol 1993;169:1000-6.

10. Rinehart BK, Terrone DA, Magann FF, Martin RW, May WL, Martin JN Jr. Preeclampsia associated hepatic hemorrhage and rupture: mode of management related to maternal and per natal outcome. Obstet Gyencol Surv, 1999;196-202.

11. Audibert F, Friedman SA, Frangieh AY, Sibai BM. Clinical utility of strict diagnostic criteria for the HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome. Clinical utility of strict diagnostic criteria for the HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets) syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996 Aug;175(2):460-4.

12. Sheikh RA, Yasmeen S, Pauly MP, Riegler JL. Spontaneous intrahepatic hemorrhage and hepatic rupture in the HELLP syndrome: four cases and a review. J Clin Gastroenterol 1999;28:323-8.

14. Risseeuw JJ, de Vries JE, Van Eyck J, Arabian B. Hepatic rupture postpartum associated with preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome. J Matern Fetal Med 1999;8:32-5.

15. Carlson KL, Bader CL. Ruptured subcapsular hepatic hematoma in pregnancy: a case report of nonsurgical management. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2004;190(2):558-60.

ARTIGO 3

Título: Síndrome HELLP: Considerações acerca de Diagnóstico e Conduta

Título em ingles: HELLP Syndrome: Considerations about Diagnosis and Management

Palavras-chave: Síndrome HELLP, Trombocitopenia, Coagulação intravascular disseminada.

Keywords: HELLP syndrome, Thrombocytopenia, Disseminated intravascular

Autores:

Patricia Costa Fonsêca Meirelles Bezerra*/**

Ana Cristina Pinheiro Fernandes de Araújo**/***

Edailna Maria de Melo Dantas**

Flávio Venício Marinho Pereira**

Marcos Dias Leão**

Selma Maria Bezerra Jerônimo****

Técia Maria Oliveira Maranhão***

Maternidade Escola Januário Cicco/ Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte*

Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências da Saúde da UFRN**

Departamento de Toco-Ginecologia da UFRN***

Resumo

A síndrome HELLP é uma grave complicação da pré-eclâmpsia, cursando com elevada morbimortalidade materna e perinatal. Controvérsias ocorrem com relação à incidência, os critérios de diagnóstico e à conduta nesta síndrome. As mortes perinatais estão relacionadas com o descolamento prematuro da placenta, asfixia intra-útero e prematuridade. A utilização de altas doses de corticóide, no tratamento, parece proporcionar melhores resultados maternos e perinatais. No entanto, são necessários estudos randomizados para sua completa e segura utilização na síndrome HELLP. O maior desafio, diante desta síndrome, é o diagnóstico precoce, a intervenção oportuna e a prevenção das complicações. Sendo assim, as pacientes, com suspeita de síndrome HELLP, deverão ser encaminhadas para um serviço de assistência terciária para que sejam assistidas por uma equipe especializada e, tão logo possível, promova-se a interrupção da gestação.

Abstract

HELLP syndrome is a severe complication of preeclampsia and evolves with high maternal and perinatal mortalities. There are still important controversies related to the true incidence, diagnostic criteria and treatment. The perinatal mortality is related to abruption placenta, intra uterine distress and prematurity. Preliminary studies indicate that corticosteroid seems to improve the maternal and perinatal outcome, although further randomized studies are needed to determine its use in HELLP syndrome. Early diagnosis is crucial to determine the type of intervention and prevention of complications. Patients suspect of HELLP syndrome should be treated at a tertiary medical center and the pregnancy should be terminated because of the severity of this illness.

Introdução

Dentre as diversas manifestações clínicas da hipertensão na gravidez, inclui-se uma entidade específica, determinada síndrome HELLP, que acomete mulheres com pré-eclâmpsia grave e apresentam hemólise (H), elevação das enzimas hepáticas (EL) e plaquetopenia (LP) (Weinstein, 1982). A pré-eclâmpsia apresenta uma incidência variável de, aproximadamente, 1,5% a 3,8% em todas as gestações, em países desenvolvidos (Ventura et al., 2000), enquanto que, no Brasil, atinge valores elevados, como 7.5% (Gaio et al., 2001). É descrito que a síndrome HELLP pode acometer 4% a 12% das pacientes com pré-eclâmpsia grave (Martin et al., 1991), podendo incorrer em elevada mortalidade materna (24%) e perinatal de até 40%, apesar da assistência ao parto, de forma oportuna, com intervenção obstétrica e cuidados intensivos, realizados por equipe capacitada (Magann & Martin, 1999; Sibai, 2004).

Existem inúmeras controvérsias em vários aspectos dessa entidade clínica, principalmente, na conduta, que ocorrem, em parte, pela falta de uniformidade nos critérios para o diagnóstico da síndrome HELLP e pela carência de estudos randomizados para o seu tratamento (Sibai, 2004). É de suma importância a discussão em torno das diversas controvérsias acerca desta síndrome, tentando adequar condutas e tratamento, visando a melhores resultados maternos e perinatais.

Controvérsias no Diagnóstico

Foi descrita uma outra classificação, baseando-se na avaliação retrospectiva de 302 casos de síndrome HELLP. Utilizou, como parâmetro básico, o nível da plaquetopenia, mantendo as alterações laboratoriais prévias e associando, agora, ao comprometimento dos sistemas nervoso central, cárdio-pulmonar e renal, o que permitiu, assim, a definição em classes. Pacientes com nível sérico de plaquetas abaixo de 50.000/mm3 seria classificado como classe I, classe II entre 51.000 e 100.000/mm3; e classe III entre 101.000 e 150.000/mm3 (Martin et al., 1990; Martin et al., 1991).

Dentre aqueles que aceitam que, para firmar o diagnóstico da síndrome HELLP, são necessários os parâmetros laboratoriais, associados aos achados característicos da pré-eclâmpsia, que incluem hipertensão e proteinúria (O’Brien & Barton, 2005), há outros que descrevem síndrome HELLP com níveis tensionais normais (Sibai, 1990). Para o diagnóstico de síndrome HELLP, a maioria dos autores (Sibai et al., 1993; Magann et al, 1999; Sibai, 2004) descreve serem necessários um hemograma com contagem de plaquetas, esfregaço periférico, para pesquisa de esquizócitos, tempo de protrombina (TP), tempo de protrombina parcial ativado (TTP), níveis de AST, LDH, creatinina e bilirrubina.

magnética ou tomografia computadorizada (Barton & Sibai, 1996). Os exames laboratoriais da função hepática, alterados, parecem preceder as outras manifestações clínicas e predizer a gravidade da doença (Magann & Martin, 1999).

Sabe-se que a coagulação intravascular disseminada ocorre em 21% das pacientes com síndrome HELLP (O’Brien & Barton, 2005). Por esta razão, alguns trabalhos sugerem a realização de testes específicos, tais como: dosagem de antitrombina III, fibrinopeptídeo A, monômero de fibrina, D-dímero, plasminogênio e fibronectina. Entretanto, estes testes são onerosos, não sendo acessíveis a rotina clínica, na maioria dos casos, reservando-se apenas para pesquisas (Sibai, 1990).

A síndrome HELLP é compreendida como completa, quando a paciente, com pré-eclâmpsia grave, apresenta anemia hemolítica microangiopática na presença de nível sérico de LDH superiores a 600 UI/L, contagem de plaquetas inferior a 100.000/mm3 e níveis séricos de AST superior a 70 IU/L. A síndrome HELLP, descrita como parcial, pode apresentar apenas um ou dois desses parâmetros alterados. As complicações maternas mais graves incidem com maior freqüência, nas portadoras de síndrome HELLP completa, daí a importância de um rigoroso critério para a definição desta síndrome (Magann & Martin, 1999).

Diagnóstico Diferencial

Os níveis tensionais elevados (pressão arterial sistólica ≥ 160 mmHg e

sempre estão presentes na síndrome HELLP, podendo-se observar pacientes com hipertensão leve (30%), ou mesmo, ausência de hipertensão arterial (20%) (Sibai, 1990).

A epigastralgia pode ser o primeiro sinal de alerta e anteceder as alterações laboratoriais da síndrome HELLP, por algumas horas, o que pode confundir o obstetra, levando-o ao diagnóstico de gastrite ou colecistite (O’Brien & Barton, 2005). Algumas vezes, esta síndrome é confundida com hepatite viral, colelitíase, colecistite, refluxo esofágico, úlcera gástrica, lúpus eritematoso sistêmico, insuficiência renal aguda, síndrome hemolítica-urêmica, púrpura trombocitopênica (PTT) e esteatose hepática da gravidez (Sibai, 2004).

hemolítica-urêmica e o sistema nervoso central na PTT (Magann & Martin, 1999; O’Brien & Barton, 2005).

Controvérsias na Conduta

Embora a síndrome HELLP possa simular diversos problemas clínicos e cirúrgicos não obstétricos, sabe-se que a brevidade e confirmação, desse diagnóstico, favorecerão o prognóstico materno e fetal, uma vez que o desfecho clínico de uma mulher, com a síndrome HELLP, é usualmente caracterizado por progressivo e rápido agravamento da condição materna. A gestante, com síndrome HELLP, necessita de cuidados especiais, já padronizados, que incluem os cuidados gerais, a administração de sulfato de magnésio, terapia anti-hipertensiva e resolução da gestação (Sibai, 1990).

Pacientes, com suspeita ou confirmação de síndrome HELLP, deverão ser imediatamente hospitalizadas em unidade de saúde de referência terciária. É conduta, prioritária, a estabilização clínica materna, particularmente as alterações da coagulação, concomitantemente à avaliação da vitalidade fetal. Diante do risco de morte materna elevada e gravidade do quadro, a interrupção da gravidez está indicada, fato que não deve depender da idade gestacional (Sibai, 1990).