Caroline Measso do Bonfim

Análise da Variabilidade Genética e Expressão de HPV em

Papilomatose de Laringe

Análise da Variabilidade Genética e Expressão de HPV em

Papilomatose de Laringe

Tese apresentada como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Doutor em Microbiologia, junto ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Microbiologia, Área de Concentração - Virologia, do Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas da Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio de Mesquita Filho”, Campus de São José do Rio Preto.

Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Paula Rahal Co-orientadora: Dra. Laura Sichero

Caroline Measso do Bonfim

Análise da Variabilidade Genética e Expressão de HPV em

Papilomatose de Laringe

Tese apresentada como parte dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Doutor em Microbiologia, junto ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Microbiologia, Área de Concentração - Virologia, do Instituto de Biociências, Letras e Ciências Exatas da

Universidade Estadual Paulista “Júlio

de Mesquita Filho”, Campus de São José do Rio Preto.

Comissão Examinadora

Profa. Dra. Laura SicheroIcesp – São Paulo Co-orientadora

Prof. Dr. Enrique Mário Boccardo Pierulivo USP – São Paulo

Profa. Dra. Márcia Guimarães da Silva Unesp – Botucatu

Dra. Alessandra Vidotto

Faculdade de Medicina de São José do Rio Preto

Dra. Cíntia Bittar

Unesp – São José do Rio Preto

“A tarefa não é tanto ver aquilo que ninguém viu, mas pensar o que ninguém ainda pensou sobre aquilo que todo mundo vê.”

Aos meus pais e minhas irmãs que são

a base e incentivo para cada

Aos meus pais, Jair e Eliana, às minhas irmãs Natália e Júlia, por ter me

incentivado e ter me dado carinho sempre.

À Profa. Dra. Paula Rahal pela orientação deste trabalho, mas acima de tudo

pela amizade, confiança e aprendizado durante esses anos. Foi um privilégio tê-la

como base para minha formação profissional.

À Dra. Laura Sichero, por ter me aceitado como sua co-orientanda e

principalmente pela amizade, confiança e pela contribuição e participação

indispensável no desenvolvimento desse trabalho.

À Dra. Luisa Lina Villa, pelo profissionalismo e parceria fundamental neste

trabalho.

Ao João Simão Sobrinho pelo seu cavalheirismo e participação ativa em etapas

fundamentais desse trabalho.

Ao Dr. Rodrigo Lacerda Nogueira, médico otorrinolaringologista, por ter

cedido as amostras utilizadas neste estudo.

À TODOS os integrantes do LEGO por toda ajuda diária, compreensão, apoio e

amizade.

Às minhas amigas Carol Jardim, Cíntia, Lílian Miuki, Lenira, Marília,

Aos membros da Banca examinadora, por ter disponibilizado o seu tempo e

contribuir na finalização deste trabalho.

Ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Microbiologia.

À UNESP-IBILCE pela oportunidade e aprendizado.

Ao Instituto do Câncer do Estado de São Paulo (ICESP).

À FAPESP pelo apoio financeiro.

Capítulo I

1. INTRODUÇÃO ... 16

1.1 Papilomatose Respiratória Recorrente ... 16

1.2 Transmissão ... 16

1.3 Sintomas Clínicos ... 18

1.4 Tratamento ... 21

1.5 Papilomavírus Humano (HPV) ... 22

1.6 Variantes moleculares de HPV ... 27

2. JUSTIFICATIVA ... 28

3. OBJETIVOS ... 29

4. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS ... 30

Capítulo II

Artigo Científico 1 ... 41ABSTRACT ... 43

REFERENCES ... 52

Capítulo III

Artigo Científico 2 ... 56ABSTRACT ... 57

INTRODUCTION ... 58

MATERIAL AND METHODS ... 60

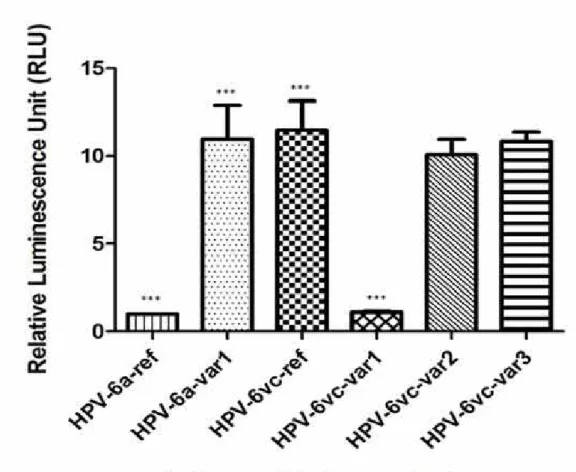

RESULTS ... 63

REFERENCES ... 69

Capítulo IV

5. DISCUSSÃO GERAL ... 73

Capítulo V

6. CONCLUSÃO ... 73

- Capítulo I

QUADRO 1. FICHA PARA CLASSIFICAÇÃO DO DERKAY SCORE_________________ 20

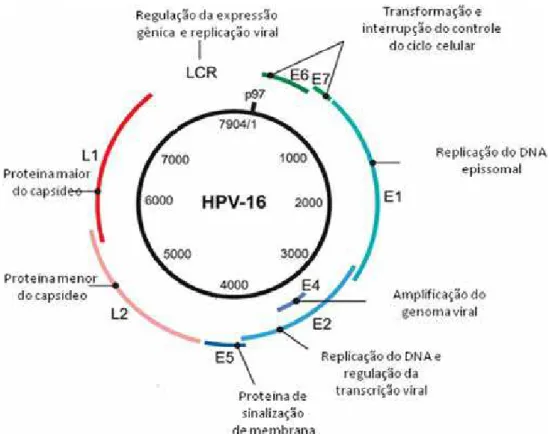

FIGURA 1. REPRESENTAÇÃO ESQUEMÁTICA DO GENOMA DO HPV____________ 23

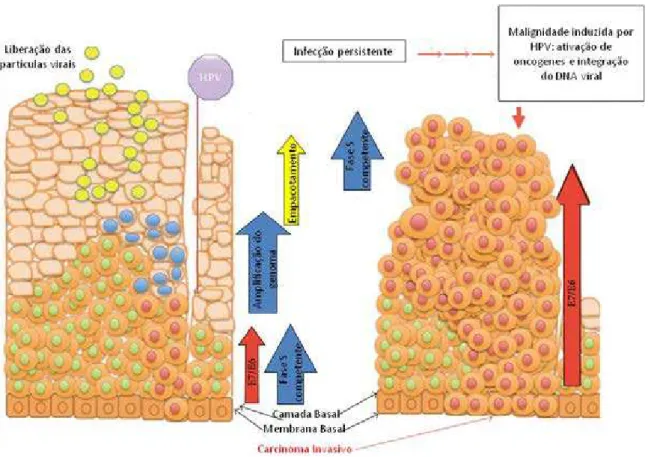

FIGURA 2. CICLO DE VIDA DO HPV_________________________________________ 25

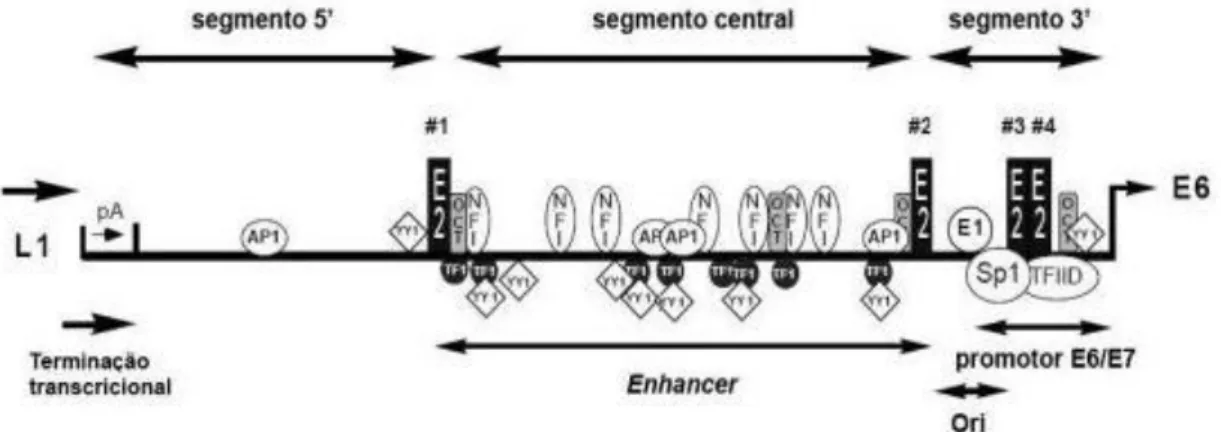

FIGURA 3. REPRESENTAÇÃO ESQUEMÁTICA DA LCR DO HPV________________ 26

- Capítulo II

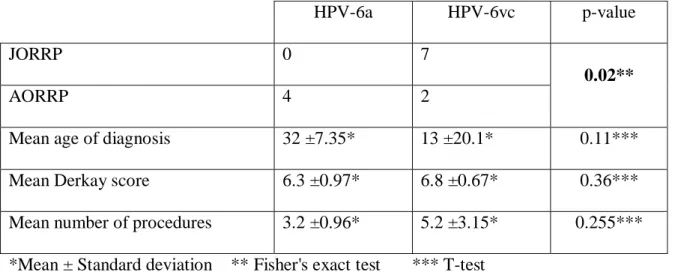

FIGURE 1. COMPARISON OF CLINICAL DATA OF RRP INDIVIDUALS___________46

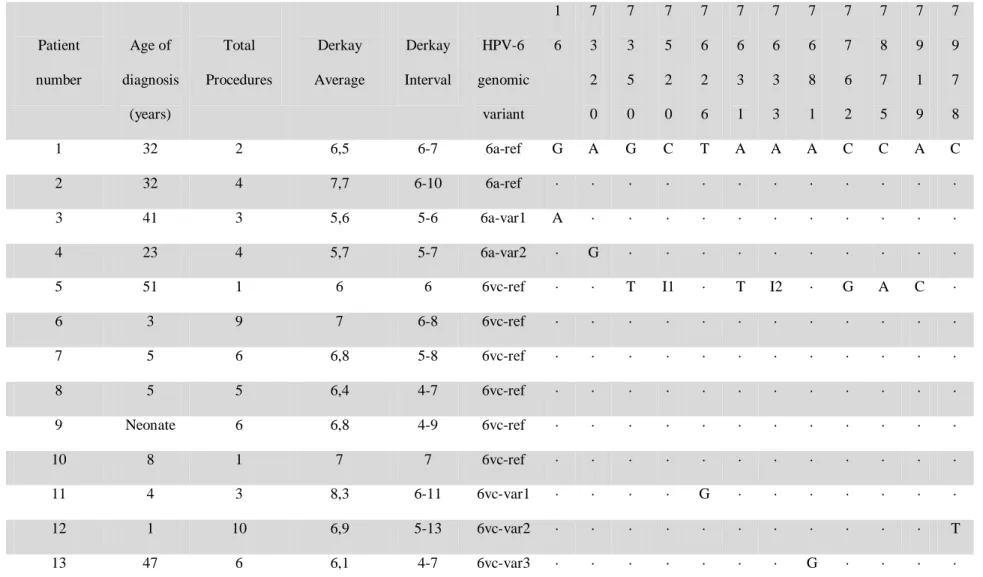

TABLE 1. CLINICAL DATA OF RRP INDIVIDUALS AND LCR GENETIC VARIABILITY OF HPV-6 MOLECULAR VARIANTS___________________________________________48

- Capítulo III

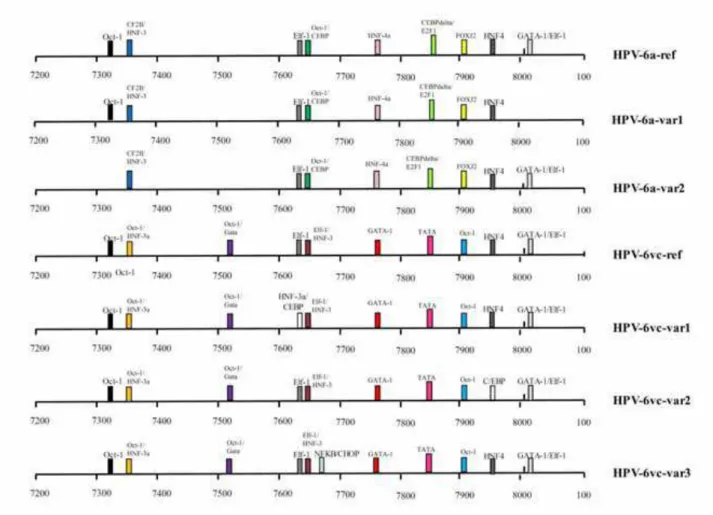

FIGURE 1. POTENTIAL BINDING SITES IN THE LCR OF HPV-6________________ 64

Lista de Siglas e Abreviaturas

AA – Variante Asiático-Americano Af – Variante Africano

AP1 – Proteína Ativadora 1 (Activator Protein -1) As – Variante Asiático

ATCC – American Type Culture Collection

BLAST – Ferramenta básica de alinhamento local (Basic Local Alignment Search

Tool)

C/EBP – Proteína de Ligação à sequência CCAAT (CCAAT enhancer binding

protein)

DNA – Ácido desoxirribonucléico (deoxyribonucleic acid) E – Variante Europeu

E6-E6AP – Proteína de associação a E6 (E6 Associated Protein) FOXA-1- Fator nuclear de hepatócito (Forkhead box protein A1) FT – Fator de transcrição

GenBank – Banco de dados de sequências do Centro de Informação sobre Biotecnologia Nacional (NCBI – National Center for Biotechnology Information)

GSTP1 - Glutationa-S-transferases pi 1 (Glutathione S-transferase pi 1)

HNF-3alpha - Fator nuclear alpha de Hepatócito (Hepatocyte nuclear factor 3-alpha)

HNF-4 – Fator nuclear 1 de Hepatócito (Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor 4) HPV – Papilomavírus Humano (Human Papillomavirus)

LCR – Região Longa de Controle (Long Control Region) NF1 – Fator Nuclear 1 (Nuclear Factor)

pRb – Proteína do Retinoblastoma (Retinoblastoma protein) PRR – Papilomatose Respiratória Recorrente

RFLP – Polimorfismo do Tamanho de Fragmentos de Restrição (Restriction

Fragment Length Polymorphism)

RLU – Unidade Relativa de Luminescência (Relative Light Unit) RNA – Àcido ribonucléico (ribonucleic acid)

RRP – Papilomatose Respiratória Recorrente (Recurrent Respiratory

Papillomatosis)

Sp1 – Fator promotor seletivo 1 (Selective promoter factor 1) TF – Fator de Transcrição (Transcription Factor)

Resumo

Abstract

Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) is a disease characterized by the formation of benign papillomas in the upper respiratory tract. Human Papillomavirus infection (HPV) is the main cause of the disease, particularly types 6 and 11 which are considered low-risk oncogenic HPV. The promoter region LCR (Long Control Region) contains cis-regulatory elements for cellular and viral transcription factors (TF) that control viral early gene expression and replication. Nucleotide alterations within the LCR may overlap TFs elements and impact upon the binding affinity, the transcriptional activity and ultimately on the clinical outcome associated to HPV infections. Our aim was to characterize molecular variants of HPV among individuals diagnosed with RRP and to analyze the impact of LCR nucleotide divergence upon viral early transcription. LCR sequencing of the HPV-6 positive samples revealed five genomic variants not previously described. Through computational analysis, we found that nucleotide changes detected overlapps potential binding sites for several transcription factors. HPV-6vc-related variant was the most prevalent among the samples analyzed (69.2%) and more prevalent in cases of juvenile papillomatosis. Concerning transcriptional activity, HPV-6vc-related variant is more active than HPV-6a molecular variant. Further, we observed that other alterations observed strongly impacts transcriptional activity indirectly measured by luciferase assays. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing differences in promoter activity among naturally occurring variants of HPV-6. Research in this area is anticipated to provide important information concerning the biological significance of HPV-6 intratype genomic variability.

16

1. INTRODUÇÃO

1.1 – Papilomatose Respiratória Recorrente

A papilomatose respiratória recorrente (PRR) é uma doença benigna caracterizada pela

formação de lesões na superfície da mucosa do trato respiratório (GOON et al., 2008).

Normalmente, a laringe é o local mais acometido pelos papilomas, porém, em casos mais

graves, as lesões podem se espalhar por todo o trato respiratório inferior (DERKAY;

WIATRAK, 2008). A papilomatose é classificada em dois tipos, de acordo com a idade do

diagnóstico: papilomatose respiratória recorrente juvenil e papilomatose respiratória

recorrente adulta (LARSON; DERKAY, 2010), sendo esta última assim definida quando

diagnosticada após os 20 anos de idade (LINDEBERG et al., 1986). A PRR é mais comum

em populações pediátricas e, geralmente, manifesta-se antes dos 5 anos de idade e em adultos

em torno de 20-40 anos(SHYKHON; KUO; PEARMAN, 2002). Com relação à etiologia da

doença, atualmente é bem estabelecida a sua associação com a infecção pelo Papilomavírus

Humano (HPV). Existem cerca de 160 tipos diferentes de HPV identificados (BERNARD et

al., 2010), sendo os tipos HPV-6 e 11 os mais comumente encontrados em PRR (DICKENS et

al., 1991). Estes dois tipos são também responsáveis por mais de 90% das verrugas genitais

(LACEY; LOWNDES; SHAH, 2006).

Apesar de sua característica benigna, a PRR pode causar morbidade e mortalidade

significativa devido à tendência de recorrência das lesões, o que leva os pacientes

necessitarem frequentemente de internação hospitalar para remoção cirúrgica dos papilomas.

Por ser uma doença negligenciada, a real incidência da PRR é desconhecida, mas estima-se

que nos Estados Unidos ocorra cerca de 1,8 casos por 100.000 habitantes em adultos e 4,3

casos por 100.000 habitantes em crianças (DERKAY; WIATRAK, 2008; GOON et al., 2008),

gerando um gasto anual de aproximadamente 123 milhões de dólares neste país (BISHAI et

al., 2000).

1.2 - Transmissão

A PRR é causada pela infecção com o Papilomavírus Humano, um vírus que pode ser

transmitido de duas maneiras: horizontal ou vertical. Na infecção horizontal, o contato sexual

com um parceiro infectado é necessário para que ocorra a transmissão. Infecções por HPV

podem ser transmitidas não apenas através das relações pênis-vagina, mas também através de

brinquedos sexuais (EDWARDS; CARNE, 1998; SONNEX et al., 1999; GERVAZ et al.,

2003). Múltiplos parceiros sexuais e alta freqüência de sexo oral são fatores relacionados com

papilomatose adulta (KASHIMA et al., 1992). No caso de PRR em adultos, também é aceita a

possibilidade de que a infecção seja uma reativação de uma exposição prévia ao vírus no

momento do nascimento, e não uma transmissão sexual, uma vez que o vírus possui a

capacidade de permanecer latente (STEINBERG et al., 1983; RIHKAREN; AALTONEN;

SYRANEN, 1993; SMITH et al., 1993).

No caso de crianças com PRR que nunca tiveram contato sexual, a transmissão

provavelmente ocorre verticalmente, ou seja, de mãe para filho, mas a fase da gestação em

que ocorre a transmissão viral ainda não está clara (CASON; MANT, 2005;

CASTELLSAGUE et al., 2009).

Na transmissão chamada peri-conceitual, acredita-se que a infecção ocorra pelo oócito

ou espermatozóide infectado. Alguns estudos detectaram de 8 a 64% de amostras positivas

para HPV no sêmen de homens assintomáticos (RINTALA et al., 2002; RINTALA et al.,

2004). Além disso, em espermatozóides infectados pelo HPV-16, foi observado que o vírus

encontrava-se transcricionalmente ativo (PAKENDORF; BORNMAN; DU PLESSIS, 1998).

Outro possível tipo de transmissão em crianças é a pré-natal, na qual o HPV pode ser

transmitido por via intrauterina através do líquido amniótico, sangue do cordão umbilical e

placenta (ARMBRUSTER-MORAES et al., 1994). O DNA do HPV foi detectado no sangue

de cordão umbilical e no líquido amniótico, com prevalência variando de 0% a 13,5%

(TSENG et al., 1992; GAJEWSKA et al., 2006; SRINIVAS et al., 2006; SARKOLA et al.,

2008) e 15% a 65%, respectivamente (ARMBRUSTER-MORAES et al., 1994; WANG;

ZHU; RAO, 1998; XU et al., 1998).

No entanto, a forma mais comum e mais aceitável de transmissão vertical do vírus é

durante o parto, por meio de exposição direta do recém-nascido às lesões cervicais e genitais

no canal de nascimento. Crianças cujas mães apresentavam condilomas genitais no momento

do parto apresentam maior risco de desenvolver a PRR (SILVERBERG et al., 2003).

Com relação à taxa de transmissão viral, a carga viral parece ser um importante fator

uma vez que alguns estudos têm mostrado que as crianças de mães com elevada carga viral no

momento do parto tiveram maiores taxas de infecção do que aquela cujas mães não

apresentaram carga viral elevada (KAYE et al., 1994; BODAGHI et al., 2005). Além disso,

18

(vaginal ou cesariana) são considerados importantes determinantes da transmissão e também

estão associados com taxas elevadas de PRR em crianças (GEREIN et al., 2007).

O tempo de exposição do bebê com o vírus é maior em mães com a primeira gravidez

que normalmente têm um longo trabalho de parto (KASHIMA et al., 1992). Com base nisso,

alguns autores sugerem que a cesariana pode reduzir o risco de transmissão da doença, devido

a redução do tempo de exposição de crianças ao HPV durante o parto, mas o quanto a

cesariana diminui as taxas de transmissão ainda é debatido. Ademais, este procedimento tem a

desvantagem de causar maior morbidade e mortalidade do que o parto normal (ARIKAN et

al., 2012).

1.3 - Sintomas Clínicos

Normalmente, a PRR afeta o trato respiratório superior, sendo as pregas vocais o

primeiro local das lesões. Outros locais extralaríngeos, como a cavidade oral, a traquéia e

esôfago, podem também ser alvos desta doença (SCHRAFF et al., 2004). Em casos mais

graves, a doença pode se disseminar e atingir brônquios e pulmão (STEINBERG;

DILORENZO, 1996).

Os sintomas mais prevalentes na papilomatose são a rouquidão e estridor (KASHIMA

et al., 1993; MCKAIG; BARIC; OLSHAN, 1998). Vários outros sintomas também podem ser

notados, como tosse, chiado, distúrbios de voz, dispnéia crônica, choro fraco em crianças,

engasgo e síncope. Em crianças, a idade de início dos sintomas varia desde o nascimento até

aproximadamente seis anos antes do diagnóstico definitivo (SILVERBERG et al., 2004). Em

adultos, ocorre tipicamente na faixa de 20 a 30 anos (DERKAY; WIATRAK, 2008).

Pelo fato da PRR ser rara e caracterizada por múltiplos sintomas, o seu diagnóstico é

difícil e muitas vezes confundido com os de outras doenças, tais como asma ou bronquite

(DERKAY; WIATRAK, 2008).

Para o diagnóstico rápido da papilomatose laríngea, os métodos mais precisos são

laringoscopia direta, endoscopia e biópsia do tecido. A doença também pode ser

diagnosticada através da detecção do DNA de HPV por meio de técnicas de biologia

molecular, como PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction), RFLP (Restriction Fragment Length

Polymorphism), PCR em tempo real e sequenciamento do genoma do HPV (DRAGANOV et

al., 2006).

A papilomatose respiratória recorrente pode ter curso clínico diferente, variando de

sofrer remissão espontânea e em outros pode ser mais agressiva, sendo necessárias muitas

cirurgias anualmente (LEE; SMITH, 2005).

1.3.1 – Classificação Clínica (escala Derkay)

A classificação clínica das lesões e severidade da papilomatose respiratória recorrente

é baseada na escala Derkay. Pelo fato da papilomatose ser uma doença com múltiplos

sintomas, curso clínico variável e diferentes respostas ao tratamento, houve a necessidade

médica de se adotar uma nomenclatura universal para classificação do estágio clínico da PRR,

permitindo assim uma comunicação eficaz entre as equipes médicas, monitoramento de

pacientes e resposta à terapia ao longo do tempo, além de disponibilizar dados que pudessem

ser utilizados como ferramenta em pesquisas clínicas. Dessa forma, foi estabelecida a escala

Derkay, que inclui uma avaliação dos parâmetros clínicos e anatômicos do paciente (Quadro

1). O cut-off da escala Derkay estabelecido para considerar uma doença severa é >10

20

Quadro 1: Modelo da ficha de avaliação para classificação do estadiamento da papilomatose respiratória recorrente (DERKAY, 1998).

Escala de Avaliação Laringoscópica e Clínica para PRR A. Classificação Clínica

1. Descreva a voz do paciente hoje:

normal___(0), anormal___(1), afônica___(2)

2. Descreva o estridor do paciente hoje:

ausente___(0), presente em atividade___(1), presente em repouso___(2)

3. Descreva a urgência hoje de uma intervenção:

programada___(0), eletiva____ (1), urgente___(2), emergencial___(3)

4. Descreva o nível de dificuldade respiratória hoje:

nenhum___(0), leve___(1), moderado___(2), severo___(3), extremo___(4)

Classificação clínica total (Questões 1 a 4) = ______ B. Classificação anatômica

Para cada local, a classificação é: 0=nenhum, 1=lesão na superfície, 2=lesão elevada, 3=lesão volumosa

LARINGE:

Epiglote: superfície lingual ___ Superfície da laringe___

Pregas ariepiglóticas: Direita___ Esquerda___

Cordas vocais falsas: Direita___ Esquerda___

Cordas vocais verdadeiras: Direita___ Esquerda___

Aritenóides: Direita___ Esquerda___

Comissura anterior______

Comissura Posterior _____

Subglote______

TRAQUÉIA:

Terço superior______

Terço médio______

Terço inferior_______

Bronquios: Direito___ Esquerdo___

Traqueostomia____ OUTROS: Nariz_______ Palato_______ Faringe_____ Esôfago___ Pulmão_______

Outro________ Classificação anatômica total __________

1.4 - Tratamento

Atualmente, nenhum tratamento específico tem sido eficaz para PRR, e uma variedade

de terapias é adotada, de acordo com o perfil de cada caso, com o objetivo de aliviar os

sintomas da doença. A cirurgia para remoção dos papilomas benignos é o principal tratamento

primário de PRR, pois preserva as vias aéreas e a boa qualidade de voz (ZEITELS et al.,

2006; GALLAGHER et al., 2009). Os procedimentos cirúrgicos mais comuns são a utilização

de microdebridador, crioterapia e laser de dióxido de carbono (SHYKHON; MKUO;

PEARMAN, 2002; DUTTA, 2011).

A traqueostomia é necessária em casos graves de pacientes que tiveram obstrução das

vias aéreas superiores devido às lesões, mas estudos têm mostrado que a utilização deste

processo pode causar a propagação de papilomas da laringe para o sistema respiratório

inferior (BLACKLEDGE; ANAND, 2000; SOLDATSKI et al., 2005).

Além dos métodos para a remoção dos tumores benignos, tratamentos adicionais com

terapias adjuvantes como os antivirais cidofovir, indol-3-carbinol, di-indolylmethane e

interferon-alfa também estão sendo administrados para a PRR. Cerca de 20% das crianças

com PRR necessitam de algum tipo de tratamento adjuvante (SCHRAFF et al., 2004;

TASCA; MCCORMICK; CLARKE, 2006; PONTES et al., 2009).

O interferon-alfa é utilizado em casos mais graves, e apresenta eficácia em cerca de

um terço dos pacientes, no entanto, vários efeitos colaterais podem ser observados

(LEVENTHAL et al., 1988; GEREIN et al., 2005).

A terapia com o antiviral cidofovir, um análogo de citosina, tem resultados

promissores no controle da recorrência dos papilomas e redução da severidade da PRR

(SPIEGEL et al., 2005). Injeções intralesionais deste antiviral no momento da cirurgia têm

sido testadas, e foi observada regressão parcial ou completa dos papilomas (PEYTON;

WIATRAK, 2004; MANDELL et al., 2004; NAIMAN et al., 2003). No entanto, há

evidências negativas com relação à segurança de cidofovir. Em animais, este antiviral é

embriotóxico, teratogênico e carcinogênico, uma vez que foi observado o aparecimento de

adenocarcinoma mamário em ratos que foram administrados a droga (WUTZLER; THUST,

2001). Além disso, displasia progressiva foi relatada em pacientes com PRR que receberam

22

Atualmente estão disponíveis duas vacinas, uma bivalente e outra quadrivalente, que

provaram ser eficazes na prevenção da infecção pelo HPV. Essas vacinas são produzidas a

partir de partículas não infecciosas chamadas VLPs (Virus Like Particles), que são estruturas

compostas pela proteína do capsídeo viral L1, da qual os epítopos são reconhecidos por

anticorpos neutralizantes (DAVID et al., 2001).

A vacina bivalente chamada Cervarix ®, da GlaxoSmithKline, oferece proteção apenas

contra os HPV-16 e 18. Os testes realizados com a Cervarix ® mostraram 100% de eficácia

na prevenção da infecção pelo HPV-16 e 18 (HARPER et al., 2004). Entretanto, a utilização

desta vacina especificamente não contribui para reduzir os casos de PRR, já que a mesma não

apresenta efeito contra os HPV-6 ou 11.

Por sua vez, a vacina quadrivalente, Gardasil®, da Merck, é eficaz contra os tipos de

HPV-6, 11, 16, 18. Estudos têm demonstrado que 99,7% dos pacientes testados

desenvolveram resposta imune à esses tipos de HPV (KOUTSKY et al., 2002; VILLA et al.,

2005). Além disso, a vacina quadrivalente foi eficaz em 92% dos casos de prevenção de

neoplasia intraepitelial cervical e 100% eficaz na prevenção de casos de condiloma

acuminado (PEREZ et al., 2008).

No entanto, apesar dessas vacinas serem eficazes profilaticamente, elas não

apresentam efeitos terapêuticos (SKJELDESTAD et al., 2008), mas é possível que a

implementação de programas de vacinação para adolescentes e mulheres adultas com a vacina

quadrivalente tenha um efeito significativo na redução da incidência da papilomatose

laríngea, uma vez que esta vacina reduz efetivamente novas infecções causadas por HPV em

sítios genitais (DERKAY; BUCHINSKY, 2007; PAWLITA; GISSMANN, 2009).

1.5 – Papilomavírus Humano (HPV)

O Papilomavírus Humano, agente etiológico da PRR, é um vírus pequeno, de

aproximadamente 8 kpb, não envelopado, que apresenta genoma circular de DNA fita dupla,

capsídeo icosaédrico e epiteliotrópico (DE VILLIERS et al., 2004). O genoma viral consiste

em três regiões: uma região promotora não codificante (Long Control Region - LCR), regiões

precoces (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6, E7) e regiões tardias (L1, L2), como pode ser observado na

Figura 1 – Representação esquemática do genoma de um Papilomavírus Humano (HPV-16), evidenciando a região regulatória (LCR), as regiões precoces (E1, E2, E4, E5, E6 e E7) e as regiões tardias (L1 e L2) (adaptado de RAUTAVA e SYRJÄNEN, 2011).

Na região precoce, os genes E1 e E2 codificam proteínas que são necessárias para

replicação e a transcrição de DNA viral (FRATTINI; LAIMINS, 1994). Tem sido sugerido

que a expressão de E1 e E2, pode ser suficiente para a manutenção de epissomos virais

(ZHANG et al., 1999). A proteína E2 atua como um repressor do promotor precoce do vírus,

funcionando como um mecanismo de controle da replicação (HOWLEY; LOWY, 2001). E4 é

expressa como uma proteína de fusão, com cinco regiões N-terminal de aminoácidos de E1

(fusão E1, E4) (DOORBAR et al., 1991). A proteína E5 induz a proliferação celular

programada, inibe a apoptose e pode ativar receptores de crescimento e proteínas quinases

(IARC, 2007). E6 e E7 são proteínas primariamente responsáveis pela transformação em HPV

de alto risco oncogênico (DYSON et al., 1989; MUNGER et al., 1989; SCHEFFNER et al.,

1990; HUIBREGTSE; SCHEFFNER; HOWLEY, 1993). A E6 dos HPVs de alto risco liga-se

diretamente á E6AP, uma proteína ubiquitina ligase celular, e este complexo E6-E6AP pode

ligar-se à p53, levando à sua degradação pela via proteossoma (SCHEFFNER et al, 1990;

24

proteassoma dependente. Esta proteína oncogênica associa-se com pRb, uma proteína

supressora de tumor e desregula o controle do ciclo celular (BOYER; WAZER; BAND,

1996). Assim, a ação oncogênica das proteínas E6 e E7 de HPV de alto risco interfere em

mecanismos importantes, tais como a apoptose, a reparação do DNA e o controle do ciclo

celular (WERNESS; LEVINE; HOWLEY, 1990; LECHNER et al., 1992; MIETZ et al.,

1992). As proteínas E6 e E7 dos HPV de baixo risco também interagem com p53 e pRb, mas

não possuem a capacidade de degradação (WERNESS; LEVINE; HOWLEY, 1990; HECK et

al., 1992; OH; LONGWORTH; LAIMINS, 2004).

A região tardia possui genes que codificam as proteínas estruturais virais L1 e L2

(SWAN; VERNON; ICENOGLE, 1994). O capsídeo viral é composto por 72 capsômeros,

sendo a proteína L1 predominante no capsídeo, e uma proporção menor de L2 embutida no

interior do invólucro de proteína.

O HPV apresenta tropismo por células epiteliais, causando infecções no tecido de

revestimento, tais como a pele e mucosas. O seu ciclo de vida, que está diretamente

relacionado ao processo de diferenciação da célula hospedeira, inicia-se com a infecção de

células epiteliais basais que provavelmente foram expostas à microtraumas, lesões ou

abrasões na epiderme (figura 2). Não se sabe ao certo qual é o receptor celular, mas alguns

estudos têm demonstrado que integrina alfa-6 e o sulfato de heparina desempenham papéis

importantes na entrada do vírus na célula (EVANDER et al., 1997; MCMILLAN et al., 1999;

ABBAN; MENESES, 2010; YOON et al., 2001).

No interior da célula, o vírus inicia a infecção de modo que o seu DNA seja expresso,

ou pode também entrar em latência viral. Quando o vírus está latente, muito pouco RNA é

expresso e a mucosa apresenta uma aparência normal e saudável. No entanto, o DNA do HPV

pode ser detectado na mucosa normal adjacente à lesão e isto pode ser a razão de muitas

recidivas em pacientes com PRR que têm ressecção total dos papilomas na cirurgia

Figura 2: Estrutura das células epiteliais escamosas e os principais estágios do ciclo de vida do HPV após a infecção (adaptado de NAGASAKA et al., 2013).

1.5.1 - A região promotora (LCR)

A LCR (Long Control Region) é uma região promotora não codificante que

compreende cerca de 10% do genoma viral, em torno de 850pb (figura3) e está localizada

entre os genes L1 e E6 (HOWLEY; LOWY, 2007). Essa região do genoma é importante para

a regulação da replicação viral e a transcrição de genes precoces, uma vez que possui sítios de

ligação para fatores de transcrição virais e celulares. A LCR pode ser dividida em três

segmentos: região 5’, segmento central e região 3’(O’CONNOR; BERNARD, 1995). A região 5’ contém sinais de terminação e poliadenilação dos transcritos virais tardios, além de possuir um sítio de ligação à matriz nuclear (TAN et al., 1998). O segmento central da LCR

contém um enhancer epitélio-específico que é mais ativo em células epiteliais do que em

26

Figura 3: A LCR do Papilomavírus Humano e a posição de ligação de vários fatores transcricionais (adaptado de O’CONNOR e BERNARD, 1995).

Alguns desses sítios de ligação na LCR estão presentes em todos os HPV, como os

sítios para os fatores AP1, E2, NF1, Oct1, Sp1 ou YY1 (CRIPE et al., 1987; OFFORD;

BEARD, 1990; THIERRY et al., 1992; APT et al., 1993; O’CONNOR; BERNARD, 1995; KANAYA; KYO; LAIMINS, 1997; STEGER; CORBACH, 1997). Os sítios de ligação para

outros fatores transcricionais são tipo-específicos (VILLA; SCHLEGEL, 1991), o que pode

explicar parcialmente a diferença do tropismo anatômico nos tipos virais (LONGWORTH;

LAIMINS, 2004). Na região 3’ está localizado o promotor responsável pela transcrição dos genes precoces, incluindo E6 e E7 (O'CONNOR; BERNARD, 1995). O promotor E6/E7

apresenta sítios de ligação conservados para E2 e a ocupação alternada desses sítios promove

diferenças no nível de atividade desse promotor (GLOSS; BERNARD, 1990; TAN; GLOSS;

BERNARD, 1992).

Até o momento, o conjunto de fatores transcricionais que se ligam na LCR tem sido

mais estudado em HPV-16 e -18, devido à sua associação com câncer cervical, e está bem

estabelecido que mutações específicas na região promotora desses tipos virais podem levar a

mudanças no comportamento de replicação viral, na atividade transcricional e na capacidade

de transformação do vírus (ROSE et al., 1998; HUBERT, 2005; KAMMER et al., 2000;

Na literatura, ainda existem poucos dados sobre quais fatores de transcrição poderiam

estar influenciando a atividade transcricional viral dos HPV de baixo risco oncogênico.

1.6 – Variantes moleculares de HPV

Um novo papilomavírus é reconhecido quando a sequência de nucleotídeos da região

L1 diverge em mais de 10% dos outros tipos já conhecidos. Diferenças na identidade entre 2%

e 10% definem um novo subtipo e aqueles com menos de 2% de diferença de nucleotídeos na

sequência de L1 caracteriza uma variante (DE VILLIERS et al., 2004). No entanto, entre

variantes moleculares, a variabilidade de nucleotídeos pode ser de até 5% na LCR, sendo

assim essa região genômica é comumente escolhida para caracterização de variantes (HO et

al.,1993). As alterações nucleotídicas como substituições, deleções ou inserções na sequência

da LCR podem afetar as propriedades patogênicas do HPV, por gerar mudanças nos sítios

ligação de fatores de transcrição e consequentemente influenciar na expressão de genes virais

(VILLA et al., 2000; BERNARD, 2002).

As análises das sequências de HPV-16 e HPV-18 de amostras cervicais positivas

provenientes do mundo todo categorizaram as variantes em linhagens filogenéticas

relacionadas em Européia (E), Asiática-Americana (AA), Asiática (As), e Africana (Af) (HO

et al., 1993; ONG et al., 1993; CHEN et al., 2005). Nesses tipos virais, foi observado que a

distribuição das variantes difere significantemente de acordo com a região geográfica

(SICHERO et al., 2006).

O HPV-6 foi descoberto em uma amostra de tecido de um condiloma acuminado

(GISSMANN; ZUR HAUSEN, 1980), sendo seu genoma completo sequenciado e designado

HPV-6b (DE VILLIERS; GISSMANN; ZUR HAUSEN, 1981). Estudos posteriores

demonstraram que o HPV-6 possuía algumas variantes genômicas (RANDO et al., 1986;

KASHER; ROMAN, 1988; FARR et al.,1991; ICENOGLE et al., 1991; YAEGASHI et al.,

1993; KITASATO et al., 1994; HEINZEL et al.,1995; GRASSMANN et al., 1996; SUZUKI

et al.,1997; CAPARROS-WANDERLEY et al., 1999). Foram então caracterizados dois

isolados estritamente relacionados ao HPV-6b, designados HPV-6a e HPV-6vc (HOFMANN

et al., 1995; KOVELMAN et al., 1999). Esses isolados de HPV-6 são comumente utilizados

para investigar variações genéticas e são agrupados em variantes protótipo (HPV-6b) e

não-protótipo (HPV-6a e HPV-6vc) (HEINZEL et al., 1995). Recentemente, com base na análise

filogenética de genomas completos de variantes de HPV-6 disponíveis na literatura, foi

28

A, e os genomas de HPV-6a e HPV-6vc à linhagem B. A linhagem B constitui ainda 3

linhagens, com HPV-6vc pertencendo a linhagem B1 e HPV-6a pertencendo a

sub-linhagem B3 (BURK et al., 2011).

Apesar das variantes moleculares serem normalmente relacionadas filogeneticamente,

elas podem apresentar patogenicidade distinta (VILLA et al., 2000; BERUMEN et al., 2001;

BURK et al., 2003; XI et al., 2007; SCHIFFMAN et al., 2010; SABOL et al., 2012; CHAN;

KLOCK; BERNARD, 2013; CORNET et al., 2013; MATOS et al., 2013). Variantes

não-européias de HPV-16 são associadas com risco aumentado para lesão cervical (XI et al.,

2002) e carcinoma anal (XI et al., 1998) em relação ao risco atribuído às variantes Européias.

Além disso, variantes não-Européias de HPV-16 e HPV-18 foram também associadas com

maior risco de infecção persistente (VILLA et al., 2000). Estudos funcionais demonstraram

ainda que variantes Asiáticas-Americanas de HPV-16 e HPV-18 são transcricionalmente mais

ativas que variantes Européias (KÄMMER et al., 2000; SICHERO; FRANCO; VILLA,

2005). Entretanto, com relação à diversidade genética dos HPV de baixo risco, como o

HPV-6, e as implicações que as variantes moleculares podem ter na patogenicidade da PRR pouco é

investigado e conhecido no Brasil.

2. JUSTIFICATIVA

A papilomatose respiratória recorrente é uma doença rara caracterizada por papilomas

benignos no trato respiratório superior e que apresenta alta morbidade devido às múltiplas

recorrências das lesões; em casos mais severos pode atingir o trato respiratório inferior e

apresentar potencial maligno (GOON et al., 2008). Essa doença é causada pela infecção com

o Papilomavírus Humano (HPV), principalmente os tipos 6 e 11.

Até o momento, mais de 180 tipos diferentes de HPV são conhecidos, dos quais cerca

de 30 infectam a mucosa epitelial (BERNARD et al., 2010). Porém, no Brasil, foram

realizados poucos trabalhos que estudam as variantes de HPV considerados de baixo risco

oncogênico como os tipos de HPV-6 e -11. O conhecimento sobre a variabilidade genética

dos variantes HPV-6 e sua relação com o desenvolvimento de papilomatose respiratória

laríngea, portanto, ainda é bastante limitado. Em estudos com HPV de alto risco, a análise da

atividade transcricional viral tem sido empregada com o objetivo de estabelecer relações entre

substituições nucleotídicas específicas na região LCR e diferenças no potencial de

malignidade entre as diferentes variantes do vírus (TORNESELLO et al., 2000; SICHERO et

Assim, devido à grande morbidade e mortalidade causadas pela PRR, uma grande

importância e atenção deve ser dispensada ao HPV-6, com o objetivo de entender melhor sua

patogenicidade e infectividade. Neste contexto este trabalho se justifica pela necessidade de se

identificar variantes de HPV-6 envolvidas na patogênese e assim, estabelecer terapias mais

adequadas às infecções e lesões causadas por esse vírus.

3. OBJETIVOS

O presente estudo teve como objetivo geral ampliar o conhecimento sobre a

variabilidade genética do HPV-6 que é comumente encontrado em papilomas de laringe, além

de verificar a possível implicação que as variações nucleotídicas na região LCR podem ter

sobre a atividade transcricional das variantes deste tipo viral.

Os objetivos específicos foram:

1. Gerar dados sobre a variabilidade genética da LCR de isolados de HPV-6 encontrados em PRR;

2. Descrever a composição de potenciais sítios de ligação para fatores transcricionais celulares e virais na LCR das variantes deste tipo viral;

3. Verificar quais alterações na sequência de nucleotídeos da LCR das variantes moleculares poderiam estar associadas à diferenças na ligação de fatores de transcrição

celulares e viral;

30

4. REFERÊNCIAS BIBLIOGRÁFICAS

ABBAN, C.Y., MENESES, P.I. Usage of heparan sulfate, integrins, and FAK in HPV16 infection. Virol, v. 403, p.1–16, 2010.

APT, D. et al. Nuclear factor I and epithelial cell-specific transcription of human papillomavirus type16. J Virol, v.67, p.4455-4463, 1993.

ARIKAN, I. et al. Cesarean section with relative indications versus spontaneous vaginal delivery: short-term outcomes of maternofetal health. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol, v.39(3), p.288-92, 2012.

ARMBRUSTER-MORAES, E. et al. Presence of human papillomavirus DNA in amniotic fluids of pregnant women with cervical lesions. Gynecol Oncol, v.54, p.152–8, 1994.

BERNARD, H.U. Gene expression of genital human papillomaviruses and considerations on potential antiviral approaches. Antivir Ther, v.7, p.219-237, 2002.

BERNARD, H. U. et al. Classification of Papillomaviruses (PVs) based on 189 PV types and proposal of taxonomic amendments. Virol, v.401, p.70-9, 2010.

BERUMEN, J. et al. Asian-American variants of human papillomavirus 16 and risk for cervical cancer: a case-control study. J Natl Cancer Inst, v. 5;93(17), p.1325-30, 2001.

BISHAI, D., KASHIMA, H., SHAH, K. The cost of juvenile-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis, Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 126, 935-939, 2000.

BLACKLEDGE, F. A.; ANAND, V. K. Tracheobronchial extension of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v.109, p.812–818, 2000.

BODAGHI, S. et al. Could human papillomaviruses be spread through blood? J Clin Microbiol, v.43, p.5428–34, 2005.

BOYER, S.N.; WAZER, D.E.; BAND, V. E7 protein of human papilloma virus-16 induces degradation of retinoblastoma protein through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Cancer Res, v. 56(20), p.4620-4, 1996.

BURK, R.D. et al. Distribution of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 variants in squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas of the cervix. Cancer Res, v. 63(21), p.7215-20, 2003.

BURK, R.D. et al. Classification and nomenclature system for human Alphapapillomavirus variants: general features, nucleotide landmarks and assignment of HPV6 and HPV11 isolates to variant lineages. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat, v.20, p.113–123, 2011.

CASON, J.; MANT, C. A. High-risk mucosal human papillomavirus infections during infancy & childhood. J Clin Virol, v. 32(Suppl. 1), p.52–8, 2005.

CASTELLSAGUE, X. et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection in pregnant women and mother-to-child transmission of genital HPV genotypes: a prospective study in Spain. BMC Infect Dis, v. 9, p. 74–86, 2009.

CHAN, W.K.; KLOCK, G.; BERNARD, H.U. Progesterone and glucocorticoid response elements occur in the long control regions of several human papillomaviruses involved in anogenital neoplasia. J Virol, v.63, p.3261-3269, 1989.

CHEN, Z. et al. Diversifying selection in human papillomavirus type 16 lineages based on complete genome analyses. J Virol, v.79, p.7014–23, 2005.

CORNET, I. et al. HPV16 genetic variation and the development of cervical cancer worldwide. Br J Cancer, v. 108(1), p.240-4, 2013.

CRIPE, T.P. et al. Transcriptional regulation of the human papillomavirus-16 E6-E7 promoter by a keratinocyte dependent enhancer, and by viral E2 trans-activator and repressor gene products: implications for cervical carcinogenesis. Embo J, v.6, p.3745-3753, 1987.

David M.K., Peter M.H., Diane E.G., Robert A.L., Malcolm A.M., Bernard R. & Stephen E.S. 2001. Fields Virology. 4th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia.

DERKAY, C. S. et al A staging system for assessing severity of disease and response to therapy in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Laryng, v.108(6), p.935-7, 1998.

DERKAY, C. S.; BUCHINSKY, F. J. Preventing recurrent respiratory papillomatosis and other HPV-associated head and neck diseases with prophylactic HPV vaccines. Am Acad Otol Head Neck Surg Bulletin, v.26, p.60–61, 2007.

DERKAY, C. S.; WIATRAK, B. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: a review. Laryng, v. 118, p.1236–1247, 2008.

De VILLIERS, E.M.; GISSMANN, L.; ZUR HAUSEN, H. Molecular cloning of viral DNA from human genital warts. J Virol, v. 40(3) p. 932-5, 1981.

De VILLIERS, E. M. et al. Classification of papillomaviruses. Virol, v. 324, p. 17-27, 2004.

DICKENS, P. et al. Human papillomavirus 6, 11, and 16 in laryngeal papillomas. J Pathol, v.165, p.243–246, 1991.

DOORBAR J. et al. Specific interaction between HPV-16 E1-E4 and cytokeratins results in collapse of the epithelial cell intermediate filament network. Nature, v.352(6338), p.824-7, 1991.

32

DUTTA, H. Recurrent Respiratory papillomatosis review. Nepalese Journal of ENT Head and Neck surgery, vol 2 No 1 Issue 1, 2011.

DYSON, N.; et al. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Scien, v.243, p.934–937, 1989.

EDWARDS, S.; CARNE,C. Oral sex and the transmission of viral STIs. Sex Transm Infect, v.74, p.6-10, 1998.

EVANDER, M. et al. Identification of the alpha6 integrin as a candidate receptor for papillomaviruses. J Virol, v.71, p.2449–2456, 1997.

FARR, A. et al. Relative enhancer activity and transforming potential of authentic human papillomavirus type 6 genomes from benign and malignant lesions. J Gen Virol, v.72, p.519-26, 1991.

FRATTINI, M.G.; LAIMINS, L.A. Binding of the human papillomavirus E1 origin-recognition protein is regulated through complex formation with the E2 enhancer-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci, v.20;91(26) p.12398-402, 1994.

FRAZER, I. H. Prevention of cervical cancer through papillomavirus vaccination. Nat Rev Immunol, v.4(1), p.46-54, 2004.

GAJEWSKA, M. et al. The occurrence of genital types of human papillomavirus in normal pregnancy and in pregnant renal transplant recipients. Neuro Endocrinol Lett, v.27, p.529– 34, 2006.

GALLAGHER, T.Q.; DERKAY, C. S. Pharmacotherapy of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: an expert opinion. Expert Opin Pharmacother, v.10, p.645-55, 2009.

GEREIN, V., et al. Use of interferon-alpha in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: 20-year follow-up. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v. 114(6), p.463-71, 2005.

GEREIN, V. et al. Human papilloma virus (HPV)-associated gynecological alteration in mothers of children with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis during longterm observation. Cancer Detect Prev, v.31, p.276–281, 2007.

GERVAZ, P. et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the anus: another sexually transmitted disease. Swiss Med Wkly, v. 133(25-26), p.353-9, 2003.

GISSMANN, L.; ZUR HAUSEN, H. Partial characterization of viral DNA from human genital warts (Condylomata acuminata). Int J Cancer, v. 25(5), p.605-9, 1980.

GLOSS, B.; BERNARD, H.U. The E6/E7 promoter of human papillomavirus type 16 is activated in the absence of E2 proteins by a sequence-aberrant Sp1 distal element. J Virol, v.64(11), p.5577-84, 1990.

GRASSMANN, K. et al. HPV6 variants from malignant tumors with sequence alterations in the regulatory region do not reveal differences in the activities of the oncogene promoters but do contain amino acid exchanges in the E6 and E7 proteins. Virol, v. 223(1), p.185-97, 1996.

HARPER, D. M. et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, v.364, p.1757–65, 2004.

HECK, D.V. et al. Eficiency of binding the retinoblastoma protein correlates with the transforming capacity of the E7 oncoproteins of the human papillomaviruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, v.89, p.4442–4446, 1992.

HEINZEL, P.A. et al. Variation of human papillomavirus type 6 (HPV-6) and HPV-11 genomes sampled throughout the world. Journal of clinical microbiology 33, 1746-1754, 1995.

HO, L. et al. The genetic drift of human papillomavirus type 16 is a means of reconstructing prehistoric viral spread and the movement of ancient human populations. J Virol, v.67, p.6413–23, 1993.

HOFMANN, K.J. et al. Sequence determination of human papillomavirus type 6a and assembly of virus-like particles in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Virol, v. 209(2), p.506-18, 1995.

HOWLEY, P.M.; LOWY, D.R. Papillomaviruses. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, eds. Fields Virology, 5th edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams, Wilkins, pp. 2299–2354, 2007.

HUBERT, W.G. Variant upstream regulatory region sequences differentially regulate human papillomavirus type 16 DNA replication throughout the viral life cycle. J Virol, v.79, p.5914-5922, 2005.

HUIBREGTSE, J. M.; SCHEFFNER, M.; HOWLEY, P.M. Localization of the E6-AP regions that direct human papillomavirus E6 binding, association with p53, and ubiquitination of associated proteins. Mol cell Biol, v.13, p.4918–4927, 1993.

IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans; v. 90, 2007.

ICENOGLE, J.P. et al. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence variation in the L1 and E7 open reading frames of human papillomavirus type 6 and type 16. Virol, v.184(1), p.101-7, 1991.

KAMMER, C. et al. Sequence analysis of the long control region of human papillomavirus type 16 variants and functional consequences for P97 promoter activity. J Gen Virol, v.81, p.1975-1981, 2000.

34

KASHER, M.S.; ROMAN, A. Alterations in the regulatory region of the human papillomavirus type 6 genome are generated during propagation in Escherichia coli. J Virol, v.62(9), p.3295-300, 1988.

KASHIMA, H. K. et al. A comparison of risk factors in juvenile-onset and adult-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Laryng, v. 102, p. 9–13, 1992.

KASHIMA, H. K. et al. Sites of predilection in recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v.102, p.580–583, 1993.

KAYE, J. N. et al. Viral load as a determinant for transmission of human papillomavirus type 16 from mother to child. J Med Virol, v.44, p.415–21, 1994.

KITASATO, H. et al. Sequence rearrangements in the upstream regulatory region of human papillomavirus type 6: are these involved in malignant transition?. J Gen Virol, v. 75, p.1157-62, 1994.

KOUTSKY, L. A. et al. A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. N Engl J Med, v.347, p.1645–51, 2002.

KOVELMAN, R. et al. Human papillomavirus type 6: classification of clinical isolates and functional analysis of E2 proteins. J Gen Virol, v. 80, p.2445-51, 1999.

LACEY, C. J.; LOWNDES, C. M.; SHAH, K. V. Chapter 4: Burden and management of non-cancerous HPV-related conditions: HPV-6/11 disease. Vaccine, v. 24 Suppl 3, p. S3/35-41, Aug 31 2006.

LARSON, D. A.; DERKAY C. S. Epidemiology of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. APMIS, v.118, p.450–454, 2010.

LECHNER, M.S. et al. Human papillomavirus E6 proteins bind p53 in vivo and abrogate p53-mediated repression of transcription. EMBO J, v.11(11), p.4248, 1992.

LEE, J. H.; SMITH, R. J. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: pathogenesis to treatment. Curr Opin in Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v. 13, p.354-359, 2005.

LEVENTHAL, B. G. et al. Randomized surgical adjuvant trial of interferon alfa-n1 in recurrent papillomatosis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v.114, p.1163–9, 1988.

LINDEBERG, H., et al. Laryngeal papillomas: classification and course. Clin Otolaryngol, v.11, p.423-9, 1986.

LONGWORTH, M.S.; LAIMINS, L.A. Pathogenesis of human papillomaviruses in differentiating epithelia. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev, v.68, p.362-372, 2004.

MATOS, R.P.A. et al. Nucleotide and phylogenetic analysis of human papillomavirus types 6 and 11 isolated from recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in Brazil. Infection, Genetics and Evolution, v. 16, p. 282-289, 2013.

MCKAIG, R. G.; BARIC, R. S.; OLSHAN, A. F. Human papillomavirus and head and neck cancer: epidemiology and molecular biology. Head Neck, v.20, p.250–265, 1998.

MCMILLAN, N. A. et al. Expression of the alpha6 integrin confers papillomavirus binding upon receptor- negative B-cells. Virol, v.261, p.271–279, 1999.

MIETZ, J.A. et al. The transcriptional transactivation function of wild-type p53 is inhibited by SV40 large T-antigen and by HPV-16 E6 oncoprotein. EMBO J, v.11(13), p.5013-20, 1992.

MUNGER, K.; et al. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J, v.8, p.4099–4105, 1989.

NAGASAKA, K. et al. PDZ Domains and Viral Infection: Versatile Potentials of HPV-PDZ Interactions in relation to Malignancy. BioMed Research International, p.1-9, 2013.

NAIMAN AN, CERUSE P, COULOMBEAU B, et al. Intralesional cidofovir and surgical excision for laryngeal papillomatosis. Laryngoscope 2003;113(12):2174–81.

O'CONNOR, M.; BERNARD, H.U. Oct-1 activates the epithelial-specific enhancer of human papillomavirus type 16 via a synergistic interaction with NFI at a conserved composite regulatory element. Virol, v.207, p.77-88, 1995.

OFFORD, E.A.; BEARD, P. A member of the activator protein 1 family found in keratinocytes but not in fibroblasts required for transcription from a human papillomavirus type 18 promoter. J Virol, v.64, p.4792-4798, 1990.

OH, S. T.; LONGWORTH, M. S.; LAIMINS, L. A. Roles of the E6 and E7 proteins in the life cycle of low-risk human papillomavirus type 11. J Virol, v.78, p.2620–2626, 2004.

ONG, C.K. et al. Evolution of human papillomavirus type 18: an ancient phylogenetic root in Africa and intratype diversity reflect coevolution with human ethnic groups. J Virol, v.67, p.6424–31, 1993.

PAKENDORF, U. W.; BORNMAN, M. S.; DU PLESSIS, D. J. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in men attending the infertility clinic. Andrologia, v.30, p.11–14, 1998.

PAWLITA, M.; GISSMANN, L. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: indication for HPV vaccination? Dtsch Med Wochenschr, v.134 Suppl 2, p.100-2, 2009.

PEREZ, G. et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in Latin American women. Int J Cancer, v.122, p.1311–18, 2008.

36

PONTES, P., et al. Aplicação local de cidofovir como tratamento adjuvante na papilomatose laríngea recorrente em crianças. Rev Assoc Med Braz, v.55(5), p.581-6, 2009.

RAIOL, T. et al. Genetic variability and phylogeny of the high-risk HPV-31, -33, -35, -52, and -58 in central Brazil. J Med Virol, v.81(4), p.685-92, 2009.

RANDO, R.F. et al. Isolation and characterization of a novel human papillomavirus type 6 DNA from an invasive vulvar carcinoma. J Virol, v.57(1), p.353-6, 1986.

RAUTAVA, J.; SYRJÄNEN, S. Human papillomavirus infections in the oral mucosa. J Am Dent Assoc, v. 142, p. 905-914, 2011.

RIHKAREN, H.; AALTONEN, L. M.; SYRANEN, S. M. Human papillomavirus in laryngeal papillomas and in adjacent normal epithelium. Clin Otolaryngol, v.18, p.470–4, 1993.

RINTALA, M. A. et al. Human papillomavirus DNA is found in vas deferens. J Infect Dis, v.185, p.1664–7, 2002.

RINTALA, M. A. et al. Detection of high-risk HPV DNA in semen and its association with the quality of semen. Int J STD AIDS, v. 15, p.740–3, 2004.

ROSE, B. et al. Point mutations in SP1 motifs in the upstream regulatory region of human papillomavirus type 18 isolates from cervical cancers increase promoter activity. J Gen Virol, v.79, p.1659-1663, 1998.

SABOL, I. et al. Characterization and whole genome analysis of human papillomavirus type 16 e1-1374^63nt variants. PLoS One, v.7(7), p.410-45, 2012.

SCHEFFNER, M.; et al. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell, v.63, p.1129–1136, 1990.

SCHRAFF, S. et al. American Society of Pediatric Otolaryngology members’ experience with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis and the use of adjuvant therapy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v.130, p.1039–1042, 2004.

SARKOLA, M. E. et al. Human papillomavirus in the placenta and umbilical cord blood. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, v.87, p.1181–8, 2008.

SHYKHON, M.; KUO, M.; PEARMAN, K. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, v.27(4), p.237-43, 2002 .

SICHERO, L.; FRANCO, E.L.; VILLA, L.L. Different P105 promoter activities among natural variants of human papillomavirus type 18. J Infect Dis, v.191, p.739-42, 2005.

SILVERBERG, M. J. et al. Condyloma in Pregnancy is strongly Predictive of Juvenile-Onset Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis. Obstetrics & Gynecology; 101(4):645-52, 2003.

SILVERBERG, M. J. et al. Clinical course of recurrent respiratory papillomatosis in Danishchildren. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v.130, p.711–716, 2004.

SHYKHON, M., KUO, M., PEARMAN, K. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci, v.27(4), p.237–243, 2002.

SKJELDESTAD, F. E. et al. Seroprevalence and genital DNA prevalence of HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18 in a cohort of young Norwegian women: study design and cohort characteristics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand, v.87, p.81–8, 2008.

SMITH, E. M. et al. Human papillomavirus infection in papillomas and nondiseased respiratory sites of patients with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis using the polymerase chain reaction. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v.119, p.554–7, 1993.

SOLDATSKI, IL, ONUFRIEVA EK, STEKLOV AM et al. Tracheal, bronchial, and pulmonary papillomatosis in children. Laryngoscope 115:1848–1854, 2005.

SONNEX, C.; STRAUSS, S.; GRAY, J. J. Detection of human papillomavirus DNA on the fingers of patients with genital warts. Sex Transm Infect, v.75(5), p.317-9, 1999.

SPIEGEL, J. H. et al. Histopathologic effects of cidofovir on cartilage. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, v.133, p.666–671, 2005.

SRINIVAS, S. K. et al. Placental inflammation and viral infection are implicated in second trimester pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol, v.75, p. 317–9, 2006.

STEGER, G.; CORBACH, S. Dose-dependent regulation of the early promoter of human papillomavirus type 18 by the viral viral E2 protein. J Virol, v.71, p.50-58, 1997.

STEINBERG, B. M. et al. Laryngeal papilloma virus infection during clinical remission. N Engl J Med, v.308, p.1261–4, 1983.

STEINBERG, B.M.; DILORENZO, T. P. A possible role for human papillomaviruses in head and neck cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev, v.15, p.91–112, 1996.

SUZUKI, T. et al. Nucleotide and amino acid sequence variations in the L1 open reading frame of human papillomavirus type 6. J Med Virol, v. 53(1), p.19-24, 1997.

SWAN, D. C.; VERNON, S. D.; ICENOGLE, J. P. Cellular proteins involved in papillomavirus-induced transformation. Arch Virol, v.138, p.105–115, 1994.

38

TAN, S.H. et al. Nuclear matrix attachment regions of human papillomavirus type 16 point toward conservation of these genomic elements in all genital papillomaviruses. J Virol, v.72(5), p.3610-22, 1998.

TASCA, R.A., MCCORMICK, M., CLARKE, R.W. British Association of Paediatric Otorhinolaryngology members experience with recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol, v. 70(7), p. 1183-7, 2006.

THIERRY, F. et al. Two AP1 sites binding JunB are essential for human papillomavirus type 18 transcription in keratinocytes. J Virol, v.66, p.3740-3748, 1992.

TORNESELLO, M.L. et al. Identification and functional analysis of sequence rearrangements in the long control region of human papillomavirus type 16 Af-1 variants isolated from Ugandan penile carcinomas. J Gen Virol, 81, 2969–2982, 2000.

TSENG, C. J. et al. Possible transplacental transmission of human papillomaviruses. Am J Obstet Gynecol, v.166, p.35–40, 1992.

VILLA, L.; SCHLEGEL, R. Differences in transformation activity between HPV-18 and HPV16 map to the viral LCR-E6-E7 region. Virol, v.181, p.374-377, 1991.

VILLA, L.L. et al. Molecular variants of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 preferentially associated with cervical neoplasia. J Gen Virol, v.81, p.2959-2968, 2000.

VILLA, L. L. et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol, v. 6, p.271–8, 2005.

WANG, X.; ZHU, Q.; RAO, H. Maternal–fetal transmission of human papillomavirus. Chin Med J, v.111, p.726–7, 1998.

WEMER, R. D. et al. Case of progressive dysplasia concomitant with intralesional cidofovir administration for recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v.114, p.836–839, 2005.

WERNESS, B. A.; LEVINE, A.J.; HOWLEY, P.M. Association of human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 E6 proteins with p53. Science, v.248, p.76–79, 1990.

WUTZLER, P.; THUST, R. Genetic risks of antiviral nucleoside analogues–a survey. Antiviral Res, v.49, p.55–74, 2001.

XI, L.F. et al. Risk of anal carcinoma in situ in relation to human papillomavirus type 16 variants. Cancer Res, v. 58, p.3839-3844, 1998.

XI, L.F. et al. Acquisition and natural history of human papillomavirus type 16 variant infection among a cohort of female university students. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, v. 11, p.343-351, 2002.

XU, S. et al. Clinical observation on vertical transmission of human papillomavirus. Chin Med Sci J, v.13, p.29–31, 1998.

YAEGASHI, N. et al. Sequence and antigenic diversity in two immunodominant regions of the L2 protein of human papillomavirus types 6 and 16. J Infect Dis, v.168(3), p.743-7, 1993.

YOON, C.S., et al. Alpha(6) integrin is the main receptor of human papillomavirus type 16 VLP. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun, v.283, p.668 –673, 2001.

ZEITELS, S. M.; et al. Office-based 532-nm pulsed KTP laser treatment of glottal papillomatosis and dysplasia. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol, v.115, p.679–685, 2006.

40

Artigo Científico 1 (em redação)

Uneven distribution of HPV-6 variants in juvenile and adult-onset recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (em redação)

Caroline Measso do Bonfim1, Laura Sichero2, Rodrigo Lacerda Nogueira3, João Simão

Sobrinho2, Daniel Salgado Kupper3, Fabiana Cardoso Pereira Valera3, Maurício Lacerda

Nogueira4, Luisa Lina Villa2,5,6, Paula Rahal1.

1- Laboratory of Genomic Studies, Universidade do Estado de São Paulo - UNESP, São Jose

do Rio Preto, SP, Brazil.

2- Molecular Biology Laboratory, Center of Translational Oncology, Instituto do Câncer do

Estado de São Paulo - ICESP, São Paulo, Brazil.

3- Department of Ophthalmology/Otorhinolaryngology and Head/Neck Surgery - Discipline

Otorhinolaryngology - Faculty of Medicine of Ribeirão Preto, Universidade de São Paulo -

USP, Brazil.

4- Laboratory of Research in Virology, Faculty of Medicine of São José do Rio Preto -

FAMERP, São Jose do Rio Preto, Brazil.

5- Department of Radiology and Oncology, School of Medicine, Universidade do São Paulo,

Brazil.

6- School of Medicine, Santa Casa de São Paulo, and HPV Institute, São Paulo, Brazil.

Running title: HPV-6 variants in laryngeal papillomatosis Journal category: Short Communication

42

Corresponding author: Paula Rahal

Laboratory of Genomic Studies, Universidade do Estado de São Paulo – UNESP

Address:

Cristóvão Colombo Street, 2265 - Jardim Nazareth

CEP 15054-000, São José do Rio Preto, São Paulo, Brazil.

ABSTRACT

Human papillomavirus (HPV) types 6 and 11 infection is the main etiological factor for

recurrent respiratory papillomatosis (RRP) development. Currently, distinct HPV molecular

variants have been shown to be an important indicator of disease pathogenesis. Our aim was

to characterize molecular variants of HPV-6 among individuals diagnosed with RRP. The

complete LCR of HPV-6 isolates from 13 patients was PCR-amplified and sequenced. From

each sample, 2 different PCR were performed. HPV-6vc related variants were more prevalent

(69%). Juvenil-onset RRP cases harbored exclusively HPV-6vc variants, whereas among

adult-onset cases HPV-6a variants were more prevalent (66.6%). Our data provides evidence

for HPV-6 variability as a viral factor that may impact the natural history of RRP.

44

Recurrent Respiratory Papillomatosis (RRP) is characterized by the proliferation of

multiple papillomas especially in the larynx. The disease is divided into juvenile (JORRP) and

adult-onset RRP (AORRP) based on the age distribution of affected individuals. Although

RRP is considered a benign disease, high recurrence rates associated with significant

morbidity and occasional mortality are observed. Human Papillomaviruses (HPV),

particularly low-risk HPVs 6 and 11 are etiologically associated with RRP development

(Donne & Clarke, 2010).

The prototype HPV-6b clone was isolated from a condyloma accuminatum specimen

(De Villiers et al., 1981). Subsequently, HPV-6a and -6vc non-prototype genomes were

characterized by variations in restriction patterns and gave rise to subtype classification.

Because the term subtype was redefined, HPV-6a, -6b and -6vc were assigned to variants

since the nucleotide sequence diverges less than 2% within the L1 late gene (Heinzel et al.,

1995). HPV-6 variants distribution is not geographically restricted (Matos et al., 2013).

HPV genomes are physically divided into three fragments: the early region, the late

region and a non-coding region (the long control region or LCR). This segment encloses cis-

elements for cellular and viral transcription factors (TF) that modulate viral early gene

expression and replication (Bernard, 2002).

HPV variability studies have largely been conducted for high-risk HPVs. However,

concerning the prevalence of low-risk HPVs and the functional implications of viral

heterogeneity, data is still scarce. We characterized LCR HPV-6 variants among RRP samples

and analyzed the association between nucleotide variability, age of disease development and

some aspects of disease severity.

Clinical samples We analyzed 23 laryngeal papilloma biopsies obtained from 13 patients

diagnosed with RRP from 2005 to 2010, and treated at the Laryngology Clinic of the School

classification severity was accessed using the Derkay system at each surgical intervention.

This scoring system relies on disease history data including total treatment period, response to

therapy, and type and extent of injury, among other clinical features (Derkay et al., 1998).

This study was approved by the Ethics Research Committee of the Universidade do Estado de

São Paulo, São José do Rio Preto Campus, and written informed consent was obtained from

all patients or parents of underage patients.

HPV-6 LCR variant analysis DNA was extracted using the QIAamp DNA Micro kit (Qiagen

Inc., Hilden, Germany). The complete HPV-6 LCR (nt 7292 to 101) was amplified using

specific primers in two independent reactions to avoid errors that may have been introduced

during amplification. After purification with the TOPO XL Gel Purification Kit (Invitrogen,

California, USA), amplicons were cloned using the pCR XL-TOPO Vector (Invitrogen,

California, USA). Four clones from each specimen were purified using the GeneJET™

Plasmid Miniprep Kit (Fermentas Life Sciences, Ontario, Canada). Sequencing reactions were

performed in a ABI 3130XL sequencer (Applied Biosystems, California, USA) using the

BigDye ® Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, California, USA).

Variants were identified after aligment of the sequences along with reference sequences of

HPV-6b (GenBank n° X00203), HPV-6a (GenBank n° L41216) and HPV-6vc (GenBank n°

AF092932) using CLUSTALW (Thompson et al., 1994) enclosed in BioEdit 7.0.9.0 package

(Hall, 1999). All variants detected were submitted to GenBank (acession number:

KF436496-KF436509).

Statistical Analysis We performed Fisher's exact test to compare HPV-6 variant distribution

between juvenile and adult-onset RRP. In addition, T-test was used to compare mean of age,

Derkay scores and number of procedures between HPV-6a related and -6vc related RRP

cases. P < 0.05 was considered significant and the GraphPad Prism® statistical package

46

We analyzed HPV-6 sequence variability in 23 biopsies from 13 RRP patients. Among

the individual enrolled in this study, age at RRP diagnosis ranged from 0 to 51. Individuals

with more than one biopsy specimen always harbored identical genomes. Overall, we detected

HPV-6a-related sequences (HPV-6a-ref, -var1, -var2) in 30.7% of the patients. HPV-6a-ref

was detected in 2 individuals, whereas HPV-6a-var1 and -6a-var2 were each detected in one

patient. Additionally, 69.2% of the individuals contained HPV-6vc-related sequences

(HPV-6vc-ref, -var1, -var2, -var3), of which HPV-6vc-ref was the most prevalent. All cases of

JORRP harbored 6vc related-variants, whereas most cases of AORRP harbored

HPV-6a-related variants (66,6%; 4/6) (p=0.02) (Figure 1). The HPV-6b prototype variant was not

detected in any of the cases analyzed.

Figure 1. Comparison of clinical data of RRP individuals infected with HPV-6a and -6vc related molecular variants.

*Mean ± Standard deviation ** Fisher's exact test *** T-test

The Derkay system was used to determine disease severity. In this cohort, Derkay

average scores ranged from 5.6 to 8.3 and were not differently distributed between HPV-6a

and -6vc cases. Nevertheless, higher number of procedures was more common in HPV-6vc

HPV-6a HPV-6vc p-value

JORRP 0 7

0.02**

AORRP 4 2

Mean age of diagnosis 32 ±7.35* 13 ±20.1* 0.11***

Mean Derkay score 6.3 ±0.97* 6.8 ±0.67* 0.36***

related infected individuals. Of the patients analyzed, only one (patient 12) was submitted to

tracheostomy.

All HPV-6vc-related isolates presented a 19bp insertion at position 7365 that had not

been detected when the ref was first described. Because this deletion in

HPV-6vc-ref was later found possibly to represent a cloning artifact (Heinzel et al., 1995; Kocjan et al.,

2009), we considered HPV-6vc-ref sequence with this insertion.Maximum genomic distance

observed was 7 mutations between HPV-6a-ref and -6vc-ref, which includes 2 insertions and

5 substitutions. HPV-6a-var1, -6a-var2, 6vc-var1, -6vc-var2 and -6vc-var3 were all found to

have unique substitutions at nucleotide positions 16 (GoA), 7320 (AoG), 7626 (ToG),

48

Table 1. Clinical data of RRP individuals included in the study and LCR genetic variabilityof HPV-6a and HPV-6vc molecular variants. Genomic positions containing specific mutations are indicated vertically across the top.

Genomic positions without mutations compared to the reference sequences (·), Insertions (I): I1= TTATTGTATATCTTGTTACA; I2= C nucleotide insertion.

Patient number Age of diagnosis (years) Total Procedures Derkay Average Derkay Interval HPV-6 genomic variant 1 6 7 3 2 0 7 3 5 0 7 5 2 0 7 6 2 6 7 6 3 1 7 6 3 3 7 6 8 1 7 7 6 2 7 8 7 5 7 9 1 9 7 9 7 8

1 32 2 6,5 6-7 6a-ref G A G C T A A A C C A C

2 32 4 7,7 6-10 6a-ref · · · ·

3 41 3 5,6 5-6 6a-var1 A · · · ·

4 23 4 5,7 5-7 6a-var2 · G · · · ·

5 51 1 6 6 6vc-ref · · T I1 · T I2 · G A C ·

6 3 9 7 6-8 6vc-ref · · · ·

7 5 6 6,8 5-8 6vc-ref · · · ·

8 5 5 6,4 4-7 6vc-ref · · · ·

9 Neonate 6 6,8 4-9 6vc-ref · · · ·

10 8 1 7 7 6vc-ref · · · ·

11 4 3 8,3 6-11 6vc-var1 · · · · G · · · ·

12 1 10 6,9 5-13 6vc-var2 · · · T