UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO NORTE

CENTRO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS

PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM ECOLOGIA

DEPARTAMENTO DE BOTÂNICA, ECOLOGIA E ZOOLOGIA

Gustavo Brant de Carvalho Paterno

O PAPEL DE INTERAÇÕES POSITIVAS ENTRE PLANTAS NA REGENERAÇÃO DE ÁREAS

DEGRADADAS NA CAATINGA

GUSTAVO BRANT DE CARVALHO PATERNO

O PAPEL DE INTERAÇÕES POSITIVAS ENTRE PLANTAS NA REGENERAÇÃO DE ÁREAS

DEGRADADAS NA CAATINGA

Dissertação Apresentada à Coordenação do Curso

de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia, da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte em cumprimento às exigências para obtenção do Grau de Mestre

Catalogação da Publicação na Fonte. UFRN / Biblioteca Setorial do Centro de Biociências

Paterno, Gustavo Brant de Carvalho.

O papel de interações positivas entre plantas na regeneração de áreas degradadas na Caatinga / Gustavo Brant de Carvalho Paterno. – Natal, RN, 2013.

95 f.: il.

Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Gislene Ganade.

Dissertação (Mestrado) – Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. Centro de Biociências. Pós-Graduação em Ecologia.

1. Restauração ecológica – Dissertação. 2. Desertificação – Dissertação 3. Germinação – Dissertação. I. Ganade, Gislene. II. Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte. III. Título.

RN/UF/BSE-‐CB CDU 574

Dedico ao simples fato das “coisas” existirem

Agradecimentos Agradecimentos Família

Antes de tudo agradeço à minha família, às minhas raízes e aos meus ancestrais. Em todos

os momentos eu tive o completo apoio de todos. Minha mãe Stella, meu pai Cesar e minhas três

irmãs, Lú, Má e Ciça. Todos eles são co-responsáveis por eu estar aqui.

Agradeço às minhas primas Paola e Fernanda e suas famílias lindas (Marcão, Artur, Felipe,

Guilherme e Letícia), que me receberam em Natal e desde então me deram apoio incondicional a

tudo que precisei. Gratidão.

Amigos

Agradeço em especial algumas pessoas que ajudaram diretamente no meu trabalho: Guedão,

Andrée, Biel, Vanessa, Márcio, Junia, Breno, Bia, Marcos (minha antiga república) e Laura, Lucão,

Luquinhas, Silvana, Nícholas, Ana e Nat (minhas república Atual); Jana obrigada por estar sempre

ali e ser você. Agredeço com muito o carinho todo o pessoal do Laboratório de Restauração da

UFRN e amigos de trabalho pelo apoio constante no campo experimental e nas ideias do meu

trabalho (Guiga, Dri, Leo, Felipe, Digo, Aninha, Marina, Tida e Fernanda). Mai, gratidão pelo

carinho imenso e pelo apoio em tantos momentos difíceis, sua ajuda foi muito importante para a

conclusão deste trabalho. Agredeço meus amigos do CRAD, José Alves, André, Jeferson, Sobrinho,

Renato, Marcos, Marcondes, Fabiana, Uêdja, Jarina, Felipe e todos os demais, obrigado por me

receberem tão bem e por terem me ajudado no campo em Petrolina. Agradeço minhas mães de

Natal, Telma e Edmar. Obrigado por terem sido minha família em terras estrangeiras.

Professores

orientaram com enorme dedicação. Agradeço em especial aos professores de Ecologia pelo grande

empenho com que se dedicaram na minha formação: Coca, Renata, Márcio, Lígia, Adriana

Monteiro, Adriana Carvalho, Gabriel, Alexandre, Carlos, Dadão, e Toti.

Com grande adimiração e carinho, gostaria de agradecer o apoio fundamental da minha

orientadora Gislene Ganade (Gis). De fato, não é possível descrever a contribuição que você

proporcionou na minha formação como pesquisador e ser humano. Realmente, muito obrigado por

mais de quatro anos trabalhando em conjunto.

Instituições

Agradeço à UFRN e e todas as pessoas brasileiras que financiaram meus estudos. Agradeço

ao CNPQ pela disponibilização de três bolsas de iniciação científica durante minha graduação. e

uma bolsa de mestrado. Agradeço ao CRAD – Centro de Referência para Recuperação de Áreas

Degradas (Caatinga), pela hospedagem e suporte em todas as necessidades dos meus dois

Sumário

Páginas

Introdução Geral... 9

Objetivos... 16

Manuscrito 1: Facilitation driven by nurse identity and target ontogeny in a degraded Brazilian semiarid dry forest... 23

Summary... 24

Introduction... 25

Methods... 28

Results... 33

Discussion... 36

References... 43

Tables... 48

Figures legends... 52

Figures... 53

Manuscrito 2: Nurse-nurse facilitation: water availability and nurse size shaping the regeneration in Brazilian semiarid lands... 57 Summary... 58

Introduction... 69

Methods... 64

Results... 70

Discussion... 73

Reference... 79

Tables... 83

Figures... 89

ANEXO 1: Fotografias manuscrito 1... 94

Introdução Geral

Caatinga, um bioma ameaçado

O Bioma Caatinga ocupa a maior parte da região semiárida brasileira, representando

aproximadamente 10% do território nacional (mais de 800 000 km2), na qual vivem mais de 25

milhões de pessoas (MMA, 2009). A maior parte da população é de baixa renda e enfrenta grande

dificuldade de acesso à água potável, devido principalmente a falta de infraestrutura e às condições

climáticas da região. O domínio das Caatingas é composto por uma grande diversidade de

fitofisionomias, variando de florestas arbóreas ou arbustivas até áreas com vegetação esparsa,

contendo pequenos arbustos, cactos e bromélias (Prado, 2005). A maioria das espécies vegetais

lenhosas apresentam características de adaptação às condições climáticas de baixa precipitação,

como a presença de espinhos, deciduidade marcante e microfilia, enquanto que as espécies

herbáceas são efêmeras e crescem apenas durante a estão chuvosa (Queiroz, 2009). Quando

comparada com outras regiões semiáridas do mundo, a Caatinga se destaca por ter alta riqueza de

espécies (aproximadamente 2000) e elevado grau endemismo (Leal et al. 2005; Leal et al. 2005b).

Apesar de boa parte do bioma ser subestimado (MMA, 2003; Leal et al. 2005), 34% das plantas,

57% dos peixes, 15 espécies de aves e 10 de mamíferos são endêmicos da Caatinga (Leal et al.

2005b).

O clima da Caatinga é caracterizado por apresentar parâmetros meteorológicos extremos

entre os biomas brasileiros (Prado, 2005). Além da grande variação na precipitação de um ano para

o outro, as condições climáticas da Caatinga envolvem alta radiação solar, baixa precipitação

(300-1000 mm-ano), alta taxa de evapotranspiração potencial (1500-2000 mm –ano) e forte

sazonalidade nas chuvas, que geralmente se concentram em apenas 3 meses do ano (Prado, 2005;

Queiroz, 2009). De uma maneira geral, 50% da área do bioma recebe menos que 750 mm-ano

enquanto que 50-70% das chuvas estão concentradas em apenas três meses, sendo que algumas

ocorrência de eventos drásticos, sejam chuvas torrenciais concentradas em curtos períodos de tempo

ou ausência completa de precipitação em alguns anos, também são fenômenos climáticos

característico da região (INSA, 2011).

Apesar de sua alta relevância ecológica, o estado de conservação do bioma é alarmante, no

qual apenas 1% da área total está protegido por unidades de conservação de proteção integral

(Hauff, 2010). Até 2008, estima-se que 45% da vegetação original já havia sido desmatada e a

degradação do bioma continua crescendo a uma taxa de 0,33% ao ano (MMA, 2010), entretanto,

outros estudos relatam que a Caatinga já perdeu 62% de sua área original enquanto que 80% já

sofreu algum tipo de alteração humana (INSA, 2011). A Caatinga enfrenta também problemas como

a fragmentação de habitat e a invasão de espécies exóticas, estando estes processos relacionados

com a extinção global de espécies (Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005). Leão et al. 2011, em

um levantamento recente sobre as espécies exóticas da Caatinga, listaram 69 espécies de animais e

51 espécies de plantas invasoras do bioma, enquanto que Castelletti et al., 2005, através de

simulações da paisagem, sugerem que a Caatinga é um bioma extremamente fragmentado, restando

poucas áreas com vegetação nativa maiores que 10.000 km2. Esse conjunto de fatores fazem da

Caatinga um dos biomas mais ameaçados do Brasil.

Atualmente as principais fontes de degradação da Caatinga são: a agricultura de corte, o

desmatamento para produção de lenha e a criação de animais com remoção da vegetação nativa

(gado e caprinos principalmente) (Leal et al. 2005b). Esses impactos associados com o aumento das

secas e a diminuição da precipitação média anual, decorrentes das mudanças climáticas, são

proponentes do processo de desertificação que afeta grandes áreas do bioma (MMA, 2007; INSA,

2011). Além disso, áreas de Caatinga que foram abandonadas após atividades de agricultura

intensiva apresentam baixa taxa de regeneração, podendo levar décadas para retornar a sua

vegetação (Pereira et al. 2003). Por fim, o avanço na degradação ambiental da Caatinga tem levado

(Leal et al. 2005b), trazendo assim, sérias consequências para a população vivente no semiárido

brasileiro.

Este cenário impõe grandes desafios para a conservação da Caatinga, os quais são agravados

pela carência econômica da região e consequente falta de investimentos do governo voltados para

conservação da biodiversidade (Leal et al. 2005; Leal et al. 2005b). Tendo o menor índice de

conhecimento científico entre os biomas brasileiros (Santos et al. 2011), a Caatinga carece

urgentemente de um maior aporte de trabalhos científicos (MMA 2003; Leal et al. 2005; MMA,

2007). Devido a existência de áreas degradadas extensas, que estão em processo de regeneração

inicial (MMA, 2009), estudos que permitam um maior entendimento dos processos que catalisam a

regeneração natural da vegetação nativa apresentam grande potencial para melhorarem a capacidade

de manejo de áreas degradadas. Tais estudos podem gerar grandes contribuições na prevenção do

avanço da desertificação, contribuindo assim para a conservação do bioma (MMA, 2003; MMA,

2007; INSA 2011).

Interações positivas e a estrutura de comunidades vegetais semiáridas

Interações entre plantas são processos centrais na estruturação de comunidades biológicas

que ocorrem ao redor do mundo (Michalet, 2006; Morin, 2012), sendo que a competição é um dos

principais mecanismos neste processo (Grime, 1973). Uma vez que espécies vegetais geralmente

utilizam os mesmos recursos para se desenvolver (água, luz e nutrientes), plantas vizinhas tendem a

interagir negativamente umas com as outras, resultando na exclusão competitiva de uma das

espécies11. Entretanto, nas últimas duas décadas, diversos estudos têm demonstrado que a

facilitação (interações positivas entre plantas), em conjunto com a competição, também é um

mecanismo chave na sucessão ecológica e na estruturação de comunidades vegetais (Callaway,

1995; Pugnaire et al. 1996; Brooker et al. 2008). Segundo Holmgren et al. (1997), a facilitação

crescimento da planta beneficiada, melhorando assim, sua chance de sobrevivência no ambiente.

Apesar de ser um fenômeno distribuído nos mais variados ecossistemas do mundo (Callway et al.

2002; Brooker et al. 2008), a facilitação têm sido registrada com mais frequência em ambientes

áridos e semiáridos (Flores & Jurado, 2003).

Nestes ambientes, nos quais o stress abiótico (pouca disponibilidade de água, elevada

temperatura do solo e alta evapotranspiração potencial) impõe grandes dificuldades para a

regeneração da comunidade vegetal, o estabelecimento da maioria das espécies em áreas sem

vegetação é bastante limitado (Franco & Nobel, 1988; Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991). Uma vez que a

sombra de indivíduos pré-estabelecidos diminui a amplitude térmica do solo e aumenta umidade, a

colonização de novas áreas por plântulas tende a ser favorecida pelo microclima menos estressante

gerado sob a copa de espécies facilitadoras (nurse plants) (Franco & Nobel, 1988; Valiente-Banuet

et al. 1991; Valiente-Banuet & Ezcurra, 1991). Muitos trabalhos têm demonstrado que além de

melhorar as condições microclimáticas do solo, estas espécies podem também aumentar a

disponibilidade de nutrientes para as plântulas, fornecendo microambientes mais adequados (“ilhas

de fertilidade”) para a germinação, estabelecimento e crescimento de espécies menos tolerantes a

stress (Pugnaire et al. 1996; Walker et al. 2001; para uma revisão dos principais mecanismos de

facilitação veja Callaway, 1995). Mesmo que as interações positivas entre plantas vizinhas ocorram

em escalas locais, seus efeitos podem repercutir em escalas mais amplas, sendo mecanismos

importantes na manutenção da biodiversidade mundial (Hacker & Gaines, 1997; Pugnaire et al.

1996; Callaway et al. 2002; Valiente-Bunet et al. 2006; Holmgren & Schefer, 2010). Estudos

recentes apontam que a facilitação contribui para o aumento da diversidade no nível da comunidade

(Pugnaire, 2010) e pode inclusive operar em escalas temporais geológicas (Valiente-Banuet et al.

2006). Estes autores, demonstraram que muitas espécies do período terciário (com clima mais

a facilitação por espécies que evoluíram no período quaternário (com clima mais seco), evitando

assim, a extinção em escala global de táxons menos tolerantes a seca (Valiente-Banuet et al. 2006).

O balanço entre facilitação e competição

De uma maneira geral, interações positivas e negativas atuam de forma conjunta, sendo o

resultado final de interações entre plantas vizinhas determinado pelo balanço líquido dessas duas

forças antagônicas (Holmgren et al. 1997; Pugnaire & Luque, 2001). A partir do recente aumento da

popularidade de interações positivas no meio científico, diversos mecanismos foram propostos para

tentar prever em quais condições a facilitação ou a competição devem prevalecer como processos

dominantes nas comunidades biológicas (Brooker et al. 2008). Na metade dos anos noventa,

Bertness & Callaway (1994) e Callaway & Walker (1997) propuseram que o balanço entre

competição e facilitação depende do grau de stress do ambiente (Hipótese do Gradiente de Stress –

SGH). Estes autores sugeriram que a frequência de interações positivas deve ser maior em

ambientes mais estressantes ou pouco produtivos enquanto que a competição deve dominar em

ambientes mais amenos ou muito produtivos (Bertness & Callaway, 1994; Callway & Walker,

1997). De acordo com estas previsões, Callaway et al. (2002), através experimentos realizados em

diversas comunidades vegetais alpinas do mundo, encontrou que a facilitação foi a interação

predominante em ambientes mais estressantes (localidades com altitude elevada), enquanto que a

competição se destacou em ambientes menos estressantes (localidades de menor altitude). Apesar

de muitos estudos corroborarem a SGH (Callaway et al. 2002; Brooker, 2008), existem vários

contraexemplos que desafiam suas previsões (Ganade & Brown, 2002; Maestre & Cortina, 2004;

Maestre et al. 2006, demonstrando que outros fatores também influenciam o balanço entre

facilitação e competição (Reginos et al. 2005). Este cenário, têm proporcionado espaço para um

intenso debate científico e o avanço teórico da ecologia vegetal, que por sua vez, possibilitou um

(Bruno et al. 2003; Michallet, 2006; Brooker et al 2008; Maestre et al. 2009; Homgreen & Scheffer,

2010).

Adicionalmente, a ontogenia das espécies envolvidas também pode ocasionar mudanças de

facilitação para competição (Valient-Banuet et al. 1991; Pugnaire et al. 1996; Rousset & Lepart,

2000; Miriti, 2006; Reisman-Berman, 2007). Valiente-Banuet et al. (1991), demonstraram em um

vale semiárido no México, que o cactos Neubuxbaumia tetetzo, após ser facilitado pelo arbusto

Mimosa luisana enquanto jovem, suprimia a planta facilitadora quando adulto, provavelmente

devido a competição por água. Miriti, (2006) também encontrou mudanças de facilitação para

competição ao longo do desenvolvimento ontogenético da espécie beneficiada, evidenciando que

indivíduos jovens cresciam melhor perto da planta facilitadora enquanto que os adultos eram

desfavorecidos. No entanto, a maioria destes estudos utilizaram métodos estatísticos baseados em

dados de associação espacial para sugerir interações positivas ou negativas entre as espécies,

existindo poucos trabalhos com experimentos de campo ou que consideraram o estágio de vida da

planta facilitadora (Pugnaire et al. 1996; Reisman-Berman, 2007). Neste sentido, existe uma grande

carência de trabalhos que testem experimentalmente como a idade ou o tamanho de plantas

facilitadoras afetam a direção e a intensidade de interações entre plantas.

Aspectos relacionados com a estratégia de vida das espécies, como a tolerância à stress,

também são considerados fatores importantes no balanço de interações entre plantas (Maestre et al.

2009). Liancourt et al. (2005), através de experimentos envolvendo espécies com diferentes

habilidades competitivas e tolerância a stress, mostraram que as espécies menos tolerantes e mais

competitivas são mais beneficiadas que espécies tolerantes a stress. Isso ocorre, justamente por que

espécies menos tolerantes são mais dependentes das condições amenas geradas na presença de

plantas vizinhas (Liancourt et a. 2005; Maestre et al. 2009). Entretanto, a maioria dos trabalhos

experimentais desenvolvidos até o momento analisaram apenas interações entre pares de espécies,

contendo muitas espécies e estratégias de vida contrastantes (Pugnaire, 2010; Xu et al. 2010). Por

exemplo, Landero & Valient-Banuet (2010) demonstraram que diferentes espécies facilitadoras

afetaram de forma distinta a dinâmica de populações de uma mesma espécie beneficiada

(Neubuxbaumia mezcalaensis), evidenciando assim, a importância de interações espécie-específicas

no balanço entre facilitação e competição (Callaway, 1998). A partir destes resultados, fica evidente

que experimentos envolvendo múltiplas espécies de plantas facilitadoras e beneficiadas podem

proporcionar um entendimento mais detalhado sobre a importância da facilitação no nível da

comunidade (Pugnaire, 2010; Xu et al. 2010). Em resumo, o balanço de interações entre plantas é

um processo complexo e dependente de muitos fatores que atuam conjuntamente, sendo muitas

vezes contexto-dependente (Reginos et al. 2005).

Neste contexto, a Caatinga se apresenta como um sistema ideal para o desenvolvimento de

experimentos e estudos envolvendo interações positivas. Uma vez que possui um clima marcado

por variações intensas na disponibilidade hídrica, a Caatinga proporciona condições experimentais

para o teste de diversas hipóteses relacionadas com o balanço entre competição e facilitação. Além

disso, existe uma grande lacuna de informação sobre o bioma, não existindo um entendimento de

quais são os principais mecanismos que estruturam suas comunidades vegetais. Até o presente

momento, o único trabalho experimental, de conhecimento do autor, que testa a importância de

interações positivas na Caatinga foi desenvolvido por Meiado, 2008, em sua dissertação de

mestrado, realizada no Parque Nacional do Catimbau. Neste estudo, o autor demonstrou que a

espécie Trischidium molle é um arbusto facilitador na Caatinga, melhorando as condições para a

germinação da comunidade regenerante sob sua copa (Meiado, 2008). Neste sentido, esta

dissertação em conjunto com trabalho de Meiado (2008), representam a abertura de uma nova área

de pesquisa para a Caatinga, evidenciando que interações positivas podem ser um processo chave

nesse bioma tão pouco estudado. Por fim, o entendimento detalhado dos mecanismos que afetam as

excelente base de referencia para projetos que visem a restauração ecológica de áreas degradadas e

a prevenção da desertificação (Gomez-Aparício et al. 2004; Gomez-Aparício, 2009; Matías et al.

2012).

Objetivo Geral

Investigar quais são os principais mecanismos e fatores que modulam as interações entre

plantas na Caatinga e como a facilitação afeta a regeneração natural de áreas degradadas e a

estruturação de comunidades vegetais nesse bioma

Objetivos Específicos

1. Manuscrito 1

a. Investigar se interações positivas são um mecanismo importante na estruturação de

comunidades vegetais da Caatinga

b. Investigar se as interações entre plantas facilitadoras e espécies beneficiadas são

espécie-específicas e como essas interações variam em função da estágio de vida das

plantas beneficiadas

2. Manuscrito 2

a. Investigar como a espécie pioneira Mimosa tenuiflora afeta as condições abióticas do

solo

b. Investigar como a facilitação entre duas espécies pioneiras varia em intensidade e

importância ao longo de um gradiente de tamanho da planta facilitadora,

Referências Bibliográficas

Bertness, M.D. & Callaway, R. (1994) Positive Interactions in Plant Community. Trends in Ecology

& Evolution, 9, 191-193.

Brooker, R.W., Maestre, F.T., Callaway, R.M., Lortie, C.L., Cavieres, L.A., Kunstler, G., Liancourt,

P., Tielboerger, K., Travis, J.M.J., Anthelme, F., Armas, C., Coll, L., Corcket, E., Delzon, S.,

Forey, E., Kikvidze, Z., Olofsson, J., Pugnaire, F., Quiroz, C.L., Saccone, P., Schiffers, K.,

Seifan, M., Touzard, B. & Michalet, R. (2008) Facilitation in plant communities: the past,

the present, and the future. Journal of Ecology, 96, 18-34.

Bruno, J.F., Stachowicz, J.J. & Bertness, M.D. (2003) Inclusion of facilitation into ecological

theory. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 18, 119-125.

Callaway, R.M. (1995) Positive interactions among plants. Botanical Review, 61, 306-349.

Callaway, R.M. (1998) Are positive interactions species-specific? Oikos, 82, 202-207.

Callaway, R.M., Brooker, R.W., Choler, P., Kikvidze, Z., Lortie, C.J., Michalet, R., Paolini, L.,

Pugnaire, F.I., Newingham, B., Aschehoug, E.T., Armas, C., Kikodze, D. & Cook, B.J.

(2002) Positive interactions among alpine plants increase with stress. Nature, 417, 844-848.

Callaway, R.M. & Walker, L.R. (1997) Competition and facilitation: A synthetic approach to

interactions in plant communities. Ecology, 78, 1958-1965.

Castelleti, C.H.M., Santos, A.M.M., Tabarelli, M. & Silva, J.M.C. (2005) Quanto ainda resta da

Caatinga? Uma estimativa preliminar. Ecologia e Conservação da Caatingapp., pp.

719-734. UFPE, Recife.

Flores, J. & Jurado, E. (2003) Are nurse-protege interactions more common among plants from arid

environments? Journal of Vegetation Science, 14, 911-916.

Franco, A.C. & Nobel, P.S. (1988) Interactions between seedlings of agave-deserti and the nurse

plant hilaria-rigida. Ecology, 69, 1731-1740.

fertility and plant litter. Ecology, 83, 743-754.

Gomez-Aparicio, L. (2009) The role of plant interactions in the restoration of degraded ecosystems:

a meta-analysis across life-forms and ecosystems. Journal of Ecology, 97, 1202-1214.

Gomez-Aparicio, L., Zamora, R., Gomez, J.M., Hodar, J.A., Castro, J. & Baraza, E. (2004)

Applying plant facilitation to forest restoration: A meta-analysis of the use of shrubs as

nurse plants. Ecological Applications, 14, 1128-1138.

Grime, J.P. (1973) COMPETITIVE EXCLUSION IN HERBACEOUS VEGETATION. Nature,

242, 344-347.

Hacker, S.D. & Gaines, S.D. (1997) Some implications of direct positive interactions for

community species diversity. Ecology, 78, 1990-2003.

Hauff, S. (2010) Representatividade do Sistema Nacional de Unidades de Conservação na

Caatinga. Programa das Nações Unidas para o Desenvolvimento, Brasília.

Holmgren, M., Scheffer, M. & Huston, M.A. (1997) The interplay of facilitation and competition in

plant communities. Ecology, 78, 1966-1975.

INSA (2011) Desertificação e Mudanças Climáticas no Semiárido Brasileiro. Instituto Nacional do

Semiárido, Campina Grande.

Leal, I.R., Da Silva, J.M.C., Tabarelli, M. & Lacher, T.E. (2005b) Changing the course of

biodiversity conservation in the Caatinga of northeastern Brazil. Conservation Biology, 19,

701-706.

Leal, I.R., Tabarelli, M. & Silva, J.M.C. (2005) Ecologia e Conservação da Caatinga. Ed.

Universitária da UFPE, Recife.

Liancourt, P., Callaway, R.M. & Michalet, R. (2005) Stress tolerance and competitive-response

ability determine the outcome of biotic interactions. Ecology, 86, 1611-1618.

Maestre, F.T., Callaway, R.M., Valladares, F. & Lortie, C.J. (2009) Refining the stress-gradient

199-205.

Maestre, F.T. & Cortina, J. (2005) Remnant shrubs in Mediterranean semi-arid steppes: effects of

shrub size, abiotic factors and species identity on understorey richness and occurrence. Acta

Oecologica-International Journal of Ecology, 27, 161-169.

Maestre, F.T., Valladares, F. & Reynolds, J.F. (2006) The stress-gradient hypothesis does not fit all

relationships between plant-plant interactions and abiotic stress: further insights from arid

environments. Journal of Ecology, 94, 17-22.

Matias, L., Zamora, R. & Castro, J. (2012) Sporadic rainy events are more critical than increasing

of drought intensity for woody species recruitment in a Mediterranean community.

Oecologia, 169, 833-844.

MEA (2005) Living Beyond our Mean: Natural assets and human well-being. Millenium

Ecosystem Assessment.

Meiado, M.V. (2008) A planta facilitadora Trischidium molle (Benth.) H. E. Ireland (Leguminosae)

e sua relação com a comunidade de plantas em ambiente semi-árido no Nordeste do Brasil.

Dissertação (Mestrado), Universidade Federal de Pernambuco.

Michalet, R., Brooker, R.W., Cavieres, L.A., Kikvidze, Z., Lortie, C.J., Pugnaire, F.I., Valiente-

Banuet, A. & Callaway, R.M. (2006) Do biotic interactions shape both sides of the humped-

back model of species richness in plant communities? Ecology Letters, 9, 767-773.

Miriti, M.N. (2006) Ontogenetic shift from facilitation to competition in a desert shrub. Journal of

Ecology, 94, 973-979.

MMA (2003) Biodiversidade da Caatinga: áreas e ações prioritárias para a conservação. MMA,

Universidade Federal de Pernanbuco, Brasília.

MMA (2007) Atlas das áreas susceptíveis à desertificação do Brasil /. MMA, Secretaria de

Recursos Hídricos, Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasília.

MMA (2010) Monitoramento dos biomas brasileiros: Bioma Caatinga. MMA, Brasília.

Morin, P.J. (2011) Community Ecology, 2 edn. A John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey.

Pereira, I.M., Andrade, L.A., Sampaio, E. & Barbosa, M.R.V. (2003) Use-history effects on

structure and flora of caatinga. Biotropica, 35, 154-165.

Prado, D.E. (2005) As Caatingas da América do Sul. Ecologia e Conservação da Caatinga (eds I.R.

Leal, M. Tabarelli & J.M.C. Silva). Editora Universitária, Recife.

Pugnaire, F.I. (2010) Positive Plant Interactions and Community Dynamics. CRC Press, New York.

Pugnaire, F.I., Haase, P., Puigdefabregas, J., Cueto, M., Clark, S.C. & Incoll, L.D. (1996)

Facilitation and succession under the canopy of a leguminous shrub, Retama sphaerocarpa,

in a semi-arid environment in south-east Spain. Oikos, 76, 455-464.

Pugnaire, F.I. & Luque, M.T. (2001) Changes in plant interactions along a gradient of

environmental stress. Oikos, 93, 42-49.

Queiroz, L.P. (2009) Leguminosas da Caatinga. Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana.

Reisman-Berman, O. (2007) Age-related change in canopy traits shifts conspecific facilitation to

interference in a semi-arid shrubland. Ecography, 30, 459-470.

Riginos, C., Milton, S.J. & Wiegand, T. (2005) Context-dependent interactions between adult

shrubs and seedlings in a semi-arid shrubland. Journal of Vegetation Science, 16, 331-340.

Rousset, O. & Lepart, J. (2000) Positive and negative interactions at different life stages of a

colonizing species (Quercus humilis). Journal of Ecology, 88, 401-412.

Santos, J.C., Leal, I.R., Almeida-Cortez, J.S., Fernandes, G.W. & Tabarelli, M. (2011) Caatinga: the

scientific negligence experienced by a dry tropical forest. Tropical Conservation Science, 4,

276-286.

Valiente-Banuet, A. & Ezcurra, E. (1991) Shade as a cause of the association between the cactus

neobuxbaumia-tetetzo and the nurse plant mimosa-luisana in the tehuacan valley, mexico.

Valiente-Banuet, A., Rumebe, A.V., Verdu, M. & Callaway, R.M. (2006) Modern quaternary plant

lineages promote diversity through facilitation of ancient tertiary lineages. Proceedings of

the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 103, 16812-16817.

Walker, L.R., Thompson, D.B. & Landau, F.H. (2001) Experimental manipulations of fertile islands

and nurse plant effects in the Mojave Desert, USA. Western North American Naturalist, 61,

25-35.

Xu, J., Michalet, R., Zhang, J.L., Wang, G., Chu, C.J. & Xiao, S. (2010) Assessing facilitative

responses to a nurse shrub at the community level: the example of Potentilla fruticosa in a

Facilitation driven by nurse identity and target ontogeny in a

degraded Brazilian semiarid dry forest

Gustavo Brant de Carvalho Paterno1

Gislene Ganade1 *

Fabiana de Arantes Basso2

José Alves de Siqueira Filho2

1Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte (UFRN), Natal, Brasil.

2Universidade Federal do Vale do São Francisco (UNIVASF), Petrolina, Brasil.

Summary

1. Facilitation by nurse plants is now widely recognized as a key process structuring plant

communities in dry lands but the mechanisms determining the net balance between

facilitation and competition remain uncertain. Most studies have focused on pair-wise

experiments that are neither able to detect species-specific interactions nor their impacts on

plant community regeneration.

2. We conducted a factorial multi-species experiment in a degraded Brazilian semi-arid forest

to test how species-specific interactions and target ontogeny modulate intensity and

direction of nurse facilitation. Seeds and seedlings of five target species were sown in the

presence and absence of three pioneer tree species and target performance was monitored

for distinct ontogenetic stages. We also measured the diversity and composition of

regenerating plant communities established under the same nurse treatments.

3. Facilitation by nurse plants was a widespread process in degraded semi-arid Caatinga since

species with completely different ecological strategies improved their germination and

establishment underneath nurse plants. Nurse plants also increased abundance and richness

of regenerating plant communities when compared with open sites. However, as targets

ontogeny developed, facilitation shifted to competition for particular target/nurse

combinations revealing that some nurses could became competitors over time.

4. Synthesis: Our results agree with previous predictions that facilitation by nurse plants can be

critical in promoting recruitment and maintaining diversity on harsh environments.

However, we provide novel experimental evidence that the balance between facilitation and

competition could be simultaneously influenced by nurse identity and target ontogeny which

strongly affect succession and restoration methods.

Key-words: Benefactor, competition, germination, establishment, restoration, Caatinga, diversity,

Introduction

Interactions among plant species are important forces influencing the structure and

composition of plant communities. Although in the past many studies focused on competition

(Grime 1977) recent research showed that positive interactions (facilitation) could play an

important role structuring plant communities (Broker et al. 2008). As facilitation and competition

act simultaneously, the net balance between these contrasting forces will determine the final

outcome of plant interactions (Holmgren et al. 1997). Interactions can shift from facilitation to

competition depending on: environmental severity (Bertness & Callaway, 1994; Lortie & Callaway,

2006), ontogeny (Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991; Rousset & Lepart, 2000; Miriti, 2006), life-form

(Gómez-Aparicio, 2009); plant density (Walker & Chapin, 1987); grazing intensity (Graff et al.

2007) and stress-tolerance ability (Liancourt et al. 2005).

Positive plant interactions have been reported for a broad range of ecosystems (Brooker et

al. 2008), from tropical and subtropical rainforests (Ganade & Brown, 2002; Zanine et al. 2006) to

arid environments where facilitation tends to be more frequent (Callaway, 1995; Flores & Jurado,

2003). While plants compete for similar resources, especially light, water and nutrients, there are

many ways one plant can improve conditions for others (Callaway, 1995 and Callaway & Walker,

1997). Facilitation occurs through amelioration of microclimatic conditions (Franco & Nobel,

1989), reduction of herbivory (Graff et al. 2007); soil nutrients improvement (Callaway, 1995) or

seed dispersal enhancement (Zanini & Ganade, 2005; Dias et al. 2005).

There is now strong evidence that nurse plants can influence plant community diversity and

function (Cavieres & Badano, 2009; Cavieres & Badano 2010). Mesquita et al. (2001) showed that

during Amazonian secondary succession pioneer species could differ in the way they influence

community regeneration by promoting alternative successional pathways with contrasting species

diversity. In a degraded Araucaria forest in Brazil, Ganade et al. (2011) found that the pioneer

hampered pine invasion, while Baccharis uncinella facilitated pine invasion and diminished plant

diversity under its crown. Facilitation effects could also improve ecosystem function by allowing

the coexistence of species with distinct ecological strategies and evolutionary histories (Cavieres &

Badano, 2010). Meanwhile, the inclusion of positive interactions on the fundamental ecological

theory is still only rising (Bruno et al. 2003; Brooker et al. 2008).

In arid and semi-arid environments plant community regeneration strongly depend on

facilitation, although ontogenetic shifts from facilitation to competition might occur as seedlings

grow (Rousset & Lepart, 2000; Ganade & Brown 2002, Miriti, 2006). Nurse shade can diminish

temperature amplitudes and decrease water evaporation providing better conditions for young

individuals to establish under water stress (Franco & Nobel, 1989; Valiente-Banuet et al. 1991).

However, studies on plant spatial distribution have shown that as target plants grow, disputes over

water and other resources may emerge. Miriti (2006) found strong ontogenetic shifts from

facilitation to competition where neighbors of Ambrosia dumosa improved juveniles performance

but suffer competition from adults. Until now, there is few experimental evidence of how plant

ontogeny can influence the intensity and direction of species-specific interactions in dry lands.

Another critical factor is that semi-arid environments tend to suffer desertification, meaning

irreversible catastrophic shifts from a vegetated to a non-vegetated state (Rietkerk et al. 2004). In

this scenario, facilitation through nurse plants might be a key process for managing ecosystems to a

recovered state. Recent studies have shown that nurse plants can be critical tools for restoration

programs (Gómez-Aparicio et al. 2004; Padilla & Cavieres, 2006), especially in semi-arid

environments (Gómez-Aparcicio, 2009).

Caatinga is a mosaic of tropical dry forest and shrubby vegetation located at northeast

Brazil. Most of its woody species loose their leaves during long periods of drought while its

herbaceous species are ephemeral and grow only during rain events. Caatinga’s climate is marked

2003). With high plant diversity and endemism, Caatinga covers nearly 10% of the Brazilian

territory. Unfortunately, this poorly protected ecosystem has been suffering intense human impact

(large areas under desertification process) and sustains the lowest score of scientific knowledge

when compared to other Brazilian ecosystems (Leal et al 2005; Santos et al. 2011, INSA, 2011).

Thus, there is a complete lack of information on the main processes governing community structure

and plant succession in degraded Caatinga lands.

We seek to answer the following questions: (i) Is facilitation by pioneer woody species an

important process structuring diversity and composition of Caatinga plant communities?; (ii) How

pioneer woody species affect seed loss, germination and establishment of a range of target

species?; (iii) Are nurse-target interactions species-specific and how this relationship changes

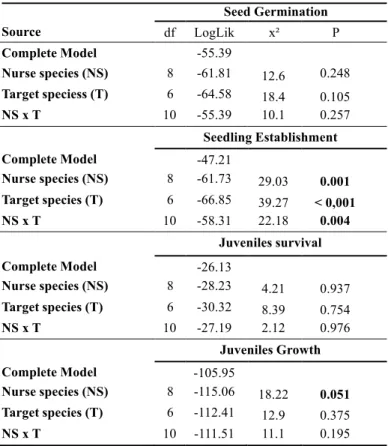

Methods

STUDY SITE

The study was conducted on a 0.5 ha site at the Centre for Restoration of Degraded Areas

(CRAD) (9º19’45,10”S 40º32’52,44”W), located near Petrolina, north-eastern Brazil. The mean

annual rainfall is 500 mm, with rainy seasons from November to April. The climate is classified as

semi-arid, characterized by periodic severe droughts and high variability of inter-annual rainfall

(Coelho, 2009).

The study site consists of a shrubby Caatinga forest that has been degraded by grazing and

logging activities during the last decades. The site has been fenced since 2005 to avoid goat

browsing. There are only 30 plant species registered in which 20 are annual herbs and 10 are woody

species. It is likely that many species became locally extinct as a result of past disturbances, severe

bare ground conditions and absence of seed sources. The following woody plants are dominant in

the area: Mimosa tenuilfora (Willd.) Poir. (Fabaceae), Poincianella microphylla (Mart. Ex G.Don)

L.P.Queiroz (Fabaceae), Jatropha mutabilis (Pohl) Baill. (Euphorbiaceae) and Cnidoscolus

quercifolius Pohl (Euphorbiaceae) (Coelho, 2009).

STUDY SPECIES

Species selected were classified into two groups: potential nurse plants (from now on nurse

plants) and target species. To select nurse plants, the following criteria were required: (I) woody

species; (ii) short period of leaf deciduousness (provides greater shade); and (iii) species common in

degraded and pristine Caatinga. Target species were selected from CRAD seed collection based on

their contrasting ecological strategies. The target species selected have rapid germination, are

woody plants, but exhibit distinct conservation status (Table 1). Three nurse plants (Cnidoscolus

quercifolius Pohl, Mimosa tenuiflora (Willd.) Poir. and Poincianella microphylla (Mart. Ex G.Don)

pyrifolium Mart, Erythrina velutina Willd., Myracrodruon urundeuva Allemão, Poincianella

pyramidalis (Tul.) L.P. Queiroz and Pseudobombax simplicifolium A. Robyns) were selected for the

seed sowing and seedling transplantation experiments (Table 1). For the seedling transplantation

experiment, A. cearensis was replaced by P. simplicifolium due to lack of available seedlings.

GREEN HOUSE GERMINATION TESTS

Seed viability and seedling establishment tests were conducted for all target species in a

greenhouse located at CRAD. For each target species (with exception of P. simplicifolium) four

replicates of thirty seeds were sown in soil plus pine bark and osmocote fertilizer. Seeds were

irrigated three times a day, light conditions were reduced by 20% under greenhouse structure. Each

seed group was placed at random on the greenhouse bench. Mechanical scarification was performed

to break E. velutina seeds dormancy (Matheus et al. 2010). The number of seeds germinated and

seedlings established was registered at two days intervals during 20 days.

SURVEY UNDER POTENTIAL NURSE PLANTS

To test if nurse plants enhance natural recruitment and affect plant community structure and

composition, an inventory of woody and Cactaceae plants was conducted in areas with and without

nurse plants. At the study site, eight adult individuals of each nurse plants (twenty four individuals

in total) were selected randomly from a pool of all eligible individuals at the site. Nurses selected

were surrounded by bare soil with no crown overlay with neighbours. A 3 x 3 m plot was delimited

with one nurse plant at the centre, comprising an area of 9 m² under the selected plant (nurse

treatment). For the “no nurse” treatment, 3 x 3m plots were implemented in adjacent open areas

randomly selected within a 7 m range from the nurse plant. In these areas, adult woody plants were

absent and bare ground frequently occurred. Pairs of plots, with and without nurse plants were

specialists.

To test if potential nurse plants enhance species richness and abundance beneath their

canopies we ran a generalized mixed model (GMM) with Poisson error distribution, “nurse effect”

as split factor and “block” as random effect (Crawley, 2007). To account for the effect of abundance

on richness, the latter was used as a response variable and the former as a covariant. The “nurse

effect” (nurse and no nurse treatments) and the “nurse species” (C. quercifolus, M. tenuiflora and P.

microphylla) were used as fixed factors. To access statistical significance of fixed factors the

deviance from the models were compared through log likelihood ratio tests.

To test if nurse plants affected plant community composition we used PERMANOVA non-

parametric test, with species abundances as response variables, “nurse effect” and “nurse species”

as explanatory variables. To solve the problem of empty samples associated with open sites, the

distances matrix was calculated with the Zero-adjusted Bray-Curtis coefficient, which considers

denude assemblages (Clarke et al. 2006). To visualize possible differences in plant community

composition between open sites and nurse plots, we plotted the two main axis of a Principal

Coordinates Analysis (PcoA) based on species abundances using Bray-Curtis distance.

FIELD EXPERIMENT

Seeds and seedlings of the five target species (A. pyrifolium, M. urundeuva, A. cearensis, E.

velutina, P. pyramidalis) were placed in the field and subjected to the presence and absence of nurse

plants. In the seedling experiment A. cearensis was replaced by P. simplicifolium. Both experiments

were implemented at the same “nurse” and “no nurse” replicates described in the previous section.

Experiments were structured in a split-plot design with target species subplots randomly assigned

within “nurse” and “no nurse” treatments (split-factor). Groups of 25 seeds of each target species

were randomly assign in each treatment. Seeds were sown 10 cm apart and marked with wooden

from 2 to 40 m. In the seedling experiment, five subplots (40 x 50cm) were delimited at the

opposite side of the seeds subplots. Four seedlings of each target species were transplanted per

subplot 25 cm apart. A total of 960 seedlings (192 per target species) were used.

Experiments started in January 2010, at the beginning of the raining season to improve

germination and survival. Seeds were collected in local Caatinga sites and stored in a low

temperature chamber (5-7 °C) for approximately six months, with exception of P. pyramidalis

seeds, which were stored for two years. All seedlings were produced in identical conditions inside

CRAD green house and were three to four months old. Before transplantation all seedlings were

subjected to acclimation in full sun and limited water for one month to simulate field conditions. All

seedlings that died at the first week after transplantation were replaced.

For the seed experiment, the number of seeds lost (predation, wind or runoff), germinated

(root emission) and the number of seedlings established (leaf emergence) were registered weekly

during five months. To test if the presence of nurse plants affected target species seed loss,

germination and seedling establishment we ran a split-plot GMM with binomial errors for each

nurse species separately. Nurse effect and target species were used as fixed factors. The significance

of each factor was tested with a log-likelihood ratio test. For the seedling experiment, the number of

survived seedlings and their height were record monthly during five months.

To access the intensity and direction of interactions between nurse plants and target species,

the relative intensity index (RII, see Armas et al. 2004) was calculated for each of the following

ontogenetic phase: germination, establishment, seedling survival and seedling growth. The RII is

calculated by the formula:

where (Bo) is the performance of target species in the absence of nurse plants and (Bw) is the

effect of nurse plant on target species, varying from -1 (maximum competition) to +1 (maximum

facilitation) (Armas et al. 2004). To test if the relationship between nurse plants and target species

were species-specific and changed with ontogeny, RII indexes (response variable)were compared

for each ontogenetic stage separately, through a linear mixed model (LMM) using “nurse species”

and “target species” treatments as factors. All statistical analysis was performed using R 2.15.0 (R

Development Core Team, 2012). GLMM models used the “lme4” package (Bates et al. 2011) and

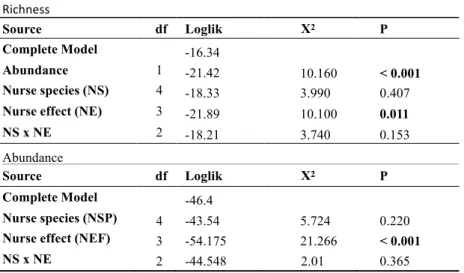

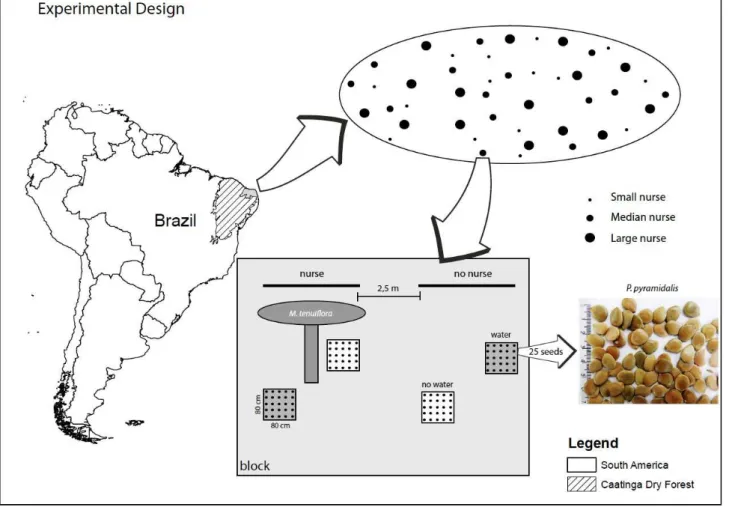

Results

GREEN HOUSE EXPERIMENT

In controlled conditions target species differed in their germination (F4,15 = 98; p < 0,001)

and establishment performance (F4,15 = 48; p < 0,001). A. pyrifolium (17% and 11% ); P.

pyramidalis (91% and 84%); A. cearensis (85% and 85%); E. velutina (86% and 67% ); and M.

urundeuva (56% and 53%) for germination and establishment respectively. Despite differences

between targets, most seeds that germinated were able to establish.

SURVEY UNDER NURSE PLANTS

Richness and abundance of woody seedlings found under nurse plants were much higher

than in areas without nurses. Under nurses abundance ranged from 2-12 times higher and richness

from 2-16 times higher (Fig. 1a and1b). Despite positive effects of abundance on species richness,

when the first was included as covariant in the model, “nurse effect” still explained richness

significantly (Table 2). All nurse plants showed similar effects on species richness and abundance

and there were no interactions among factors (Table 2).

Composition of the regenerating plant community differed between open areas and nurse

canopy (Fig. 1c, F45,1 = 8.79; p < 0.001; Table s1 in supplementary material), however, there was no

difference between nurse species (F45,2 = 1.18; p = 0.297). Ninety-two individuals of eight species

were found under the canopy of nurse plants, encompassing four families (Burseraceae, Cactaceae,

Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae), 37 under C. quercifolius, 31 under M. tenuiflora and 24 under P.

microphylla ( Table s2, supplementary material). Four species were only found under the canopy of

nurse plants (Commiphora leptophloeos, Melocactus zehntneri (endemic & endangered), Tacinga

inamoena (endemic) and Mimosa tenuiflora. In open areas only 13 individuals of four species were

found all occurring under nurse canopy. The presence of nurses increased species, genus and

surveys.

TRANSPLANTATION EXPERIMENTS

In general, nurse plants had no effect on seed loss, with the exception of P. microphylla that

showed a significant interaction between “nurse effect” and “target species” indicating species-

specific interactions (Fig. 2b; Table 3). Target species had different probabilities of seed loss, M.

urundeuva and E. velutina had the highest rates while the other targets showed probabilities equal

or lower than 20% (Fig. 2abc).

The presence of nurse plants had a strong positive effect on seed germination probability for

all target species, increasing it from 2 to 9 fold, depending on the target species identity (Table 3;

Fig. 2def). For the nurse C. quercifolius there was a significant interaction between “nurse effect”

and “target species”, demonstrating that target species differed in the way their germination

performance was positively affected by this nurse (Table 3). For instance, A. cearencis showed

higher seed germination improvements when compared with other targets (Fig. 2d).

When considering seedling establishment, the presence of nurse plants also had positive

effects on target species (although marginal for P. mycrophylla ) (Table 3, Fig. 2ghi). Because few

seedlings of A. pyrifolium, E. velutina and A. cearensis were able to establish, the nurse effect on

these target species could not be fully detected. However, nurse plants improved seedling

establishment for P. pyramidalis and M. urundeuva.

Although nurses improved targets early performance, all experimental plants (6000 seeds

and 960 seedlings) died within six months due to atypical drought. Precipitation during this time

was 64-75% lower than what is historically expected for the first three months of the growing

season.

FACILITATION VERSUS COMPETITION

developed (Fig. 3, Table 4). Facilitation prevailed during germination and survival phases with no

significant differences between nurse and target species (Fig. 3a and 3c). Nonetheless, seedling

establishment performance showed a significant “nurse” “target” interaction, with some

combinations being neutral or minor while others showed extreme values of facilitation (Fig. 3b).

For example, M. urundeuva was extremely facilitated by C. quercifolius and P. microphylla and not

affected by M. tenuiflora, while A. cearensis was only facilitated by M. tenuiflora and not affected

by other nurses. Additionally, nurse plants affected target latter development in different ways, P.

microphylla facilitates, C. quercifolius was neutral and M. tenuiflora showed negative effects on

target growth (Fig. 3d). As a whole, P. microphylla was the nurse that showed the most consistent

Discussion

Facilitation by nurse plants was widespread in degraded areas of the semi-arid Caatinga as

predicted by the stress gradient hypothesis (Bertness & Callaway, 1994; Callaway & Walker, 1997).

This is so because species with completely different ecological strategies improved their

germination and establishment underneath nurse plants that are common in Caatinga dry forest

degraded areas . Positive effects of nurse plants on seed germination and seedling establishment

have been registered for a wide range of ecosystems (Callaway, 1995; Zanini et al. 2006; Brooker et

al. 2008). However, most facilitation experiments have been restricted to pairwise interactions,

while only few studies have accessed the impact of facilitation in multiple-species experiments or at

the entire community level (Cavieres & Bandano, 2009; Landero & Valiente-Banuet, 2010). This

facilitation processes unveiled by our experiment is most likely to be driven by the unsuitable

abiotic conditions found in Caatinga open sites, such as drought, high soil temperatures and direct

radiation. Thus, as demonstrated for others dry ecosystems, microclimatic amelioration by nurse

plants seems to be the major mechanism promoting better establishment and survival at this plant

community (Gómez-Aparicio et al. 2004).

This work also provides novel experimental results highlighting that the balance between

facilitation and competition could be simultaneously influenced by nurse species identity and target

species ontogeny. For seed germination, facilitation was a widespread phenomenon regardless nurse

identity. However, as target ontogenetic development progressed, differences between nurse plants

became clear. P. microphylla remained a good benefactor improving target species growth, while C.

quercifolius and M. tenuiflora, depending on the target species in question, showed neutral and/or

negative effects. These results indicate that plant community regeneration may strongly depend on a

broad range of nurse species that can facilitate distinct arrays of plant functional groups at different

ontogenetic stages (Callaway, 1998; Landero & Valient-Banuet, 2010). Thus, species-specific

future composition (Mesquita et al. 2001; Rousset & Lepart, 2000; Ganade et al. 2011).

Nurse characteristics that control their distinct influence on target species performance are

yet to be unveiled. Differences in root structure and soil use strategies may lead to micro scale

differences in soil properties beneath distinct nurse species. Nurse canopy size and architecture are

also important factors affecting nurse performance and can influence the net balance between

facilitation and competition (Tewksbury & Lloyde, 2001). Interactions between nurse size and

water stress are still poorly tested, but Reisman-Berman (2007) found age-related interactions in a

semiarid shrub ecosystem, where nurse effect changed from positive for young nurses to negative

for old nurses. In the semi-arid Caatinga, nurses that are able to increase environmental water

availability are most likely to facilitate target species. In our study, best and worse facilitators

exhibited very similar ecological and morphological characteristics, differing only in their

conservation status. However, P. microphylla and C. quercifolius are species with denser leaves

which provide greater shade. The best facilitator (P. microphylla) was an endemic species while the

worse facilitator expressed wide geographical occurrence. It is plausible that endemic species would

be less aggressive in the way they explore water while wide occurrence species would be more

efficient in competing for this key resource. Future works should look at how morphological traits

and geographical distribution of nurse species would reflect their facilitation skills.

It is well recognized that ontogenetic changes influence the net balance of competition and

facilitation in arid environments (Miriti, 2006). However, we do not have knowledge of multiple-

species experiments that tested how ontogeny affects intensity and direction of plant interactions

(but see Rouseet et al. 2000). Our results show that depending on the ontogenetic stage of target

species, nurse influence may change from facilitation to competition. During early ontogenetic

phases (germination) all target species were benefited by the presence of all nurse plants studied.

Water stress may be an important force controlling this pattern because all species showed much

plants could compensate part of this stress improving germination by more than 3 times in some

cases. For latter ontogenetic stages (seedlings), nurse species started to compete with target species

decreasing their ability to grow beneath nurse shelter. In semiarid environments rainfall is

extremely unpredictable, with long drought intervals (Prado, 2003). For successful performance,

seedlings need to grow to a certain size to withstand the next drought period otherwise they may die

due to tissue fragility (Fenner & Thompson 2005). Our results indicate that when more sensitive

target species interact with a resource demanding nurse, improvements of the key resource (water)

provided by this nurse may not be sufficient to overcome negative effects of nurse competition by

other resources (Holmgren et al. 1997). Future studies should go beyond the early stages of

development to fully access the role of ontogeny on plant interactions and succession.

Previous works have shown that positive interactions can enhance community richness by

enlarging realized niche or releasing intolerant species from stress (Bruno et al. 2003; Michalet et

al. 2006). If so, one would expect to find higher species richness and different species composition

beneath nurse canopies when compared with open areas. In agreement with these predictions our

results corroborate the hypothesis that facilitation by nurse plants increase community richness

(Cavieres & Badano, 2009). Additionally, many species found under nurses were not found in open

areas showing that a range of plants, including endemic and endangered species, could be locally

extinct in the absence of nurses. These data suggest that less-tolerant species depend on specific

sheltered conditions provided by nurses to establish and survive (Zonneveld et al. 2012), therefore,

nurse plants appear to play a key role in maintaining local diversity at all taxonomic levels

(Cavieres & Badano, 2010).

Increased plant regeneration under nurse trees could also be attributed to an increased rate of

seed arrival bellow nurses, because seed dispersers tend to use nurse structure as perches (Zanini &

Ganade 2005; Dias et al. 2005). We attribute minor importance to this type of indirect facilitation

Moreover, this possible lack of nurse ability to attract dispersers would restrict colonization of a

range of sensitive target plants that have to perform long distance travelling. Indeed, we did not find

any of our experimentally studied target species present in our community regeneration survey.

These findings would explain why we did not encounter detectable differences in community

regeneration among nurse species. Future works should look at the relative importance of dispersal

and facilitation as drivers of secondary succession where nurse plants seem to catalyze the

regeneration of various species and functional groups (Fuentes-Castillo et al 2012).

IMPLICATIONS FOR ECOLOGICAL RESTORATION IN SEMIARID LANDS

The potential for using nurse plants as tools for restorations programs are now widely

recognized for different ecosystems (Padilla & Pugnaire, 2006; Gómes-Aparicio 2009). Our results

points out that pioneer shrubs and trees are good candidates to be used in restoration programs of

semiarid degraded lands (Gómes-Aparicio 2009). Our survey has shown that nurse plants are

critical for maintaining endemic and endangered species in degraded areas. However, we found

strong evidence that nurse plant positive effects are not enough to restrain mortality in drier years,

in agreement with the refined stress-gradient hypothesis (Maestre et al. 2009). Therefore, during

drought events the use of nurse-assisted technics by itself may be inefficient. New studies should

test if nurse plants combined with artificial irrigation could be an option to achieve successful target

species establishment during restoration. A second major challenge for the use of nurse-assisted

technics is to fully understand how species-specific interactions affect natural regeneration. This

fine-scale comprehension could provide direct insights into which species should be used as nurse

plants forbetter results on local plant community regeneration (Gómes-Aparicio 2009). Complex

interaction may arise among different nurse plants and target species because facilitation effects can

be highly depended on nurse identity and target ontogeny. Therefore, restoration programs that aim