Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for

the Treatment of Depressive Disorders in

Primary Care: A Systematic Review

Thomas Grochtdreis1*, Christian Brettschneider1, Annemarie Wegener1, Birgit Watzke2, Steffi Riedel-Heller3, Martin Härter4, Hans-Helmut König1

1Department of Health Economics and Health Services Research, Hamburg Center for Health Economics, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany,2Clinical Psychology and

Psychotherapy Research, Institute of Psychology, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland,3Institute of Social Medicine, Occupational Health and Public Health, University of Leipzig, Leipzig, Germany,

4Department of Medical Psychology, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany

*t.grochtdreis@uke.de

Abstract

Background

For the treatment of depressive disorders, the framework of collaborative care has been recommended, which showed improved outcomes in the primary care sector. Yet, an earlier literature review did not find sufficient evidence to draw robust conclusions on the cost-ef-fectiveness of collaborative care.

Purpose

To systematically review studies on the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care, compared with usual care for the treatment of patients with depressive disorders in primary care.

Methods

A systematic literature search in major databases was conducted. Risk of bias was as-sessed using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool. Methodological quality of the articles was assessed using the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list. To ensure compa-rability across studies, cost data were inflated to the year 2012 using country-specific gross domestic product inflation rates, and were adjusted to international dollars using purchasing power parities (PPP).

Results

In total, 19 cost-effectiveness analyses were reviewed. The included studies had sample sizes between n = 65 to n = 1,801, and time horizons between six to 24 months. Between 42% and 89% of the CHEC quality criteria were fulfilled, and in only one study no risk of bias was identified. A societal perspective was used by five studies. Incremental costs per de-pression-free day ranged from dominance to US$PPP 64.89, and incremental costs per QALY from dominance to US$PPP 874,562.

OPEN ACCESS

Citation:Grochtdreis T, Brettschneider C, Wegener A, Watzke B, Riedel-Heller S, Härter M, et al. (2015) Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for the Treatment of Depressive Disorders in Primary Care: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 10(5): e0123078. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123078

Academic Editor:Brett Thombs, McGill University, CANADA

Received:December 8, 2014

Accepted:February 27, 2015

Published:May 19, 2015

Copyright:© 2015 Grochtdreis et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the

Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement:All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files

Conclusion

Despite our review improved the comparability of study results, cost-effectiveness of collab-orative care compared with usual care for the treatment of patients with depressive disor-ders in primary care is ambiguous depending on willingness to pay. A still considerable uncertainty, due to inconsistent methodological quality and results among included studies, suggests further cost-effectiveness analyses using QALYs as effect measures and a time horizon of at least 1 year.

Introduction

In 2010, major depressive disorder (MDD) accounted for 2.5% of the world’s total global bur-den of disease expressed in disability-adjusted life years (DALY) and ranked second with re-spect to years lived with disabilities (YLD) [1]. In Europe, lifetime prevalence estimations of MDD range from 11.6% to 17.1% with comorbidities being highly prevalent [2–5].

Mean annual costs per patient with MDD in Europe have been estimated at€3,034, of

which€1,251 were due to (non-)medical treatment (direct costs) and€1,782 were due to

re-duced productivity (indirect costs) [6]. A review of cost-of-illness studies of depression esti-mated the average annual direct excess costs for a depressed individual at US$1,000 to US $2,500 [7].

MDD is associated with one or more episodes of depressed mood or loss of interest in plea-sure in nearly all activities over a period of at least two weeks [8]. MDD requires treatment be-cause otherwise substantial psychosocial problems may occur [9]. Patients with sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild depression are advised by clinical practice guidelines to be treated with low-intensity psychological interventions and group cognitive behavioral therapy. Pa-tients with moderate to severe depression are advised to be treated either with an antidepres-sant medication or high-intensity psychological interventions alone, or with a combination of both [10,11]. The clinical practice guideline of the English National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) [10] also advises to use the framework of a stepped-care model to organize the provision of services, and support patients, carers and physicians in identifying and accessing the most effective interventions. The steps of such a model should consist of psy-choeducation, active monitoring, medication and psychosocial interventions.

One way to use the framework of stepped-care and to coordinate care is represented by the collaborative care approach, which is particularly recommended for patients with persistent sub-threshold depressive symptoms or mild to moderate depression with inadequate response to initial interventions, and moderate to severe depression [10]. Collaborative care is a multi-faceted intervention that targets patient, physician and structural aspects of care. Treating phy-sicians should be able to coordinate care, guide treatment based on relevant information and synchronize decisions and treatments by ongoing contact with other professionals [12]. Collab-orative care was initially developed to improve treatment of depression and short-term clinical outcomes [13]. According to Barkil-Oteo [14], collaborative care improves care for depression in different settings and populations, especially in the primary care sector, which plays a central role in the mental health system and the treatment of depression. Collaborative care for pa-tients with depression was found to be effective in terms of depression outcomes, antidepres-sant use and quality of life [15–17].

In order to compare the costs and outcomes of collaborative care with usual care or an alter-native intervention, cost-effectiveness analyses (CEAs) are applied. In CEAs, a ratio between

the differences in costs and the differences in effects of alternative treatments is calculated. One earlier literature review published by van Steenbergen-Weijenburg et al. [18] in 2009 systemati-cally examined cost-effectiveness studies of (stepped) collaborative care for patients with major depressive disorders in the primary care setting. The economic evidence was not sufficient to draw robust conclusions on the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for patients with depres-sive disorders. To our knowledge, no more recent systematic review on this topic exists, al-though several new cost-effectiveness trials on collaborative care for patients with depressive disorders have been published in the last years, such as from the PROMODE study [19], the MDDP study [20] or the TEAM study [21,22].

The aim of this paper is to systematically review studies on the cost-effectiveness of (stepped) collaborative care compared with usual care for the treatment of patients with de-pressive disorders in primary care. It provides an update and extension of the literature review by van Steenbergen-Weijenburg et al. [18] by adding recently published studies to the quantita-tive analysis, improving the comparability of studies by means of inflating and adjusting costs to international dollars, and assessing the quality and risk of bias of included studies.

Materials and Methods

Search methods

A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, PsychINFO, Embase, Cinahl, Econ-Lit, the Cochrane Library and NHS EED in March 2014 and was updated in February 2015 using a validated rapid review method to minimize time lag of this review [23]. The following search term was used: (depressive disorder OR depression) AND (collaborative care OR disease management OR stepped care) AND (cost-benefit analysis OR cost-effectiveness OR cost-utili-ty OR economic evaluation). Subject headings were additionally used, when applicable. Fur-thermore, references of studies included in qualitative synthesis and of reviews excluded during eligibility assessment were screened for further eligible studies. The literature search was not limited to any publication year. The studies from the previous review [18] were incor-porated in the current review. Articles without abstracts were not included in the data analysis.

Inclusion of studies

Title and abstract of all articles were independently screened for relevance by two authors (TG and AW). Articles that were deemed relevant were considered in full text. On disagreement, consensus was reached by involving a third author (CB). Full texts of all potentially relevant studies were assessed and included, when

• a cost-effectiveness analysis was presented

• the intervention was (stepped) collaborative care, and

• the study population consisted of patients with depressive disorders.

Articles were excluded if they were protocols, letters, editorials, conference abstracts, case reports, reviews, if the study objectives were other than evaluation of cost-effectiveness of col-laborative care, if studies only described decision-analytic models, or if the full text was not available in English or German.

[24]. Accordingly, programs were defined as collaborative care if treatment complied with at least three of the following four criteria [18]:

1. “Within [(stepped)] collaborative care the role of care manager is introduced to assist and manage the patient by providing structured and systematic interventions.

2. A network is formed around the patient with at least two (. . .) professionals [(e.g. primary

care physician, care manager, and/or consultant psychiatrist)] (. . .) [13,25].

3. Process and outcome of treatment is being monitored and in case of insufficient improve-ment, treatment may be changed according to the principles of stepped care [26].

4. Evidence-based treatment is provided [(e.g. on the basis of a clinical practice guideline [10, 11])] [26].”

Quality assessment and data abstraction

The risk of bias in studies included in this review was assessed using the Cochrane Collabora-tion’s tool [27] addressing seven specific domains (sequence generation, allocation conceal-ment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessconceal-ment, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and‘other issues’). For the economic evaluation as-pects of the articles, the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria (CHEC) list for economic evaluations [28] was used as a quality criteria list. The CHEC-list addresses 19 categories as-sessing methodological quality of economic evaluations [28]. If necessary, information was re-trieved from related studies or protocols when they were stated as source. Two authors (TG and AW) independently assessed the risk of bias of the studies as well as the methodological quality of the economic evaluations. Discussion or third opinion (CB) was used in case of dis-agreement. Independently from the methodological quality and the risk of bias of each study, all available evidence was used for analysis to avoid loss of information. Risk of bias data was processed graphically with Review Manager 5.3 [29].

All abstracted data (e.g. perspectives, effect measurements, cost measurements, incremental cost-effectiveness or cost-utility ratios) from each selected study was entered into spreadsheets.

Analysis of included studies

As summary measures, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) in terms of incremental costs per depression-free day (DFD), per quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) or per other out-comes were reported.

Results

Study selection

In total, 736 articles were identified. Based on title and abstract screening for relevance, 197 du-plicates and 487 non-relevant articles were removed. From the remaining 52 potentially rele-vant articles, full texts were retrieved and examined for relevance. Thirty-five were rejected (15 reviews, 2 conference abstracts, 7 no collaborative care, 10 no cost-effectiveness analysis, 1 only subgroup analysis). An update of the systematic literature search identified two additional arti-cles. Finally, 19 studies were included in the review [33–51]. Through the search, all eight stud-ies included in the literature review by van Steenbergen-Weijenburg et al. [18] were identified. A flow chart of the selection process is presented inFig 1.

Study characteristics

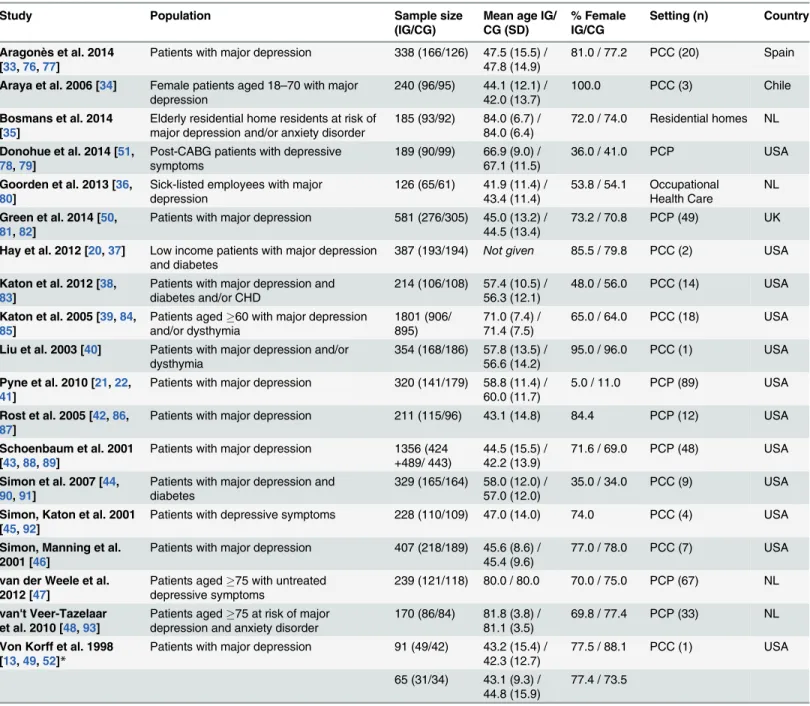

The general characteristics of the included CEA are presented inTable 1. The included studies originated from the United States (n = 12), the Netherlands (n = 4), Chile (n = 1), Spain (n = 1) and the United Kingdom (n = 1). The earliest study was published in 1998 [49] and the most recent were published in 2014 [33,50,51]. All but three studies were multicenter trials con-ducted in primary care clinics (n = 10), primary care practices (n = 7), residential homes (n = 1) or an occupational health care setting (n = 1). The mean number of centers was 22, ranging from one to 89 centers.

Fig 1. Flow chart of the selection process based on the PRISMA Statement [75].

The sample size varied from N = 65 in one trial with a single center to N = 1,801 in a trial with 18 centers (mean sample size N = 392). All studies focused on patients with depressive disorders alone, with depressive symptoms or at risk of depressive disorders. Three studies only included patients with comorbid diabetes [37,44], or both, diabetes and coronary heart disease [38]. One study only included patients with depressive symptoms following coronary artery bypass graft [51]. The mean age of the patients varied from 42 years to 84 years (overall Table 1. General characteristics of the included studies.

Study Population Sample size

(IG/CG)

Mean age IG/ CG (SD)

% Female IG/CG

Setting (n) Country

Aragonès et al. 2014

[33,76,77]

Patients with major depression 338 (166/126) 47.5 (15.5) / 47.8 (14.9)

81.0 / 77.2 PCC (20) Spain

Araya et al. 2006 [34] Female patients aged 18–70 with major depression

240 (96/95) 44.1 (12.1) / 42.0 (13.7)

100.0 PCC (3) Chile

Bosmans et al. 2014 [35]

Elderly residential home residents at risk of major depression and/or anxiety disorder

185 (93/92) 84.0 (6.7) / 84.0 (6.4)

72.0 / 74.0 Residential homes NL

Donohue et al. 2014 [51,

78,79]

Post-CABG patients with depressive symptoms

189 (90/99) 66.9 (9.0) / 67.1 (11.5)

36.0 / 41.0 PCP USA

Goorden et al. 2013 [36,

80]

Sick-listed employees with major depression

126 (65/61) 41.9 (11.4) / 43.4 (11.4)

53.8 / 54.1 Occupational Health Care

NL

Green et al. 2014 [50,

81,82]

Patients with major depression 581 (276/305) 45.0 (13.2) / 44.5 (13.4)

73.2 / 70.8 PCP (49) UK

Hay et al. 2012 [20,37] Low income patients with major depression and diabetes

387 (193/194) Not given 85.5 / 79.8 PCC (2) USA

Katon et al. 2012 [38,

83]

Patients with major depression and diabetes and/or CHD

214 (106/108) 57.4 (10.5) / 56.3 (12.1)

48.0 / 56.0 PCC (14) USA

Katon et al. 2005 [39,84,

85]

Patients aged60 with major depression and/or dysthymia

1801 (906/ 895)

71.0 (7.4) / 71.4 (7.5)

65.0 / 64.0 PCC (18) USA

Liu et al. 2003 [40] Patients with major depression and/or dysthymia

354 (168/186) 57.8 (13.5) / 56.6 (14.2)

95.0 / 96.0 PCC (1) USA

Pyne et al. 2010 [21,22,

41]

Patients with major depression 320 (141/179) 58.8 (11.4) / 60.0 (11.7)

5.0 / 11.0 PCP (89) USA

Rost et al. 2005 [42,86,

87]

Patients with major depression 211 (115/96) 43.1 (14.8) 84.4 PCP (12) USA

Schoenbaum et al. 2001 [43,88,89]

Patients with major depression 1356 (424 +489/ 443)

44.5 (15.5) / 42.2 (13.9)

71.6 / 69.0 PCP (48) USA

Simon et al. 2007 [44,

90,91]

Patients with major depression and diabetes

329 (165/164) 58.0 (12.0) / 57.0 (12.0)

35.0 / 34.0 PCC (9) USA

Simon, Katon et al. 2001 [45,92]

Patients with depressive symptoms 228 (110/109) 47.0 (14.0) 74.0 PCC (4) USA

Simon, Manning et al. 2001 [46]

Patients with major depression 407 (218/189) 45.6 (8.6) / 45.4 (9.6)

77.0 / 78.0 PCC (7) USA

van der Weele et al. 2012 [47]

Patients aged75 with untreated depressive symptoms

239 (121/118) 80.0 / 80.0 70.0 / 75.0 PCP (67) NL

van't Veer-Tazelaar et al. 2010 [48,93]

Patients aged75 at risk of major depression and anxiety disorder

170 (86/84) 81.8 (3.8) / 81.1 (3.5)

69.8 / 77.4 PCP (33) NL

Von Korff et al. 1998 [13,49,52]*

Patients with major depression 91 (49/42) 43.2 (15.4) / 42.3 (12.7)

77.5 / 88.1 PCC (1) USA

65 (31/34) 43.1 (9.3) / 44.8 (15.9)

77.4 / 73.5

CABG = Coronary Artery Bypass Graft, CHD = Coronary Heart Disease, IG = Intervention Group, CG = Control Group, PCC = Primary Care Clinic, PCP = Primary Care Practice, NL = the Netherlands, UK = United Kingdom

*Analysis was based on two RCT

mean age 56 years). Four studies only included aged patients with an overall mean age of 79 years [35,39,47,48]. The overall mean percentage of included female patients was 68%, rang-ing from 8% in the study by Pyne et al. [41], where the settrang-ing was a veteran population, to 100% in the study by Araya et al. [34], where only women were included on purpose.

A societal perspective was used by five studies [35,36,43,47,48] and eleven studies used a health care perspective [34,36–41,44,45,49–51]. Both, a health care perspective and a societal perspective, was used by three studies [33,42,46].

All studies indicated that a care manager assisted and managed the patient by providing structured and systematic interventions. In ten studies, the care management was implemented by nurses/health care professionals solely [33,38,40–45,51] or, in addition, social workers [34] or psychologists [39,50], respectively. Physicians were care managers in three studies [35– 37].

In all studies, a network was formed around the patient comprising at least two profession-als [34–36,43,45,46,49]. In ten studies, the network was composed of three professionals [33, 37–40,42,47,48,50,51] and in two studies, the network was composed of four to five different professionals [41,44]. Professionals routinely associated with the network were mainly primary care physicians [33,35–47,49–51], specialized nurses [33–35,38,39,41–44,47,48,51] and psychiatrists [38–40,44,45,49,51]. Other professionals associated with the network were psy-chologists [39,40,44,50], social workers [34,37,40] and pharmacologists [41].

Monitoring was an element of collaborative care in all but two studies [35,47]. Treatment progress and response was monitored in nine studies [34,36,38–40,46,49–51] and medication or treatment adherence in twelve studies [33,34,40–46,49–51]. Symptoms were being moni-tored in six studies [34,37,41–43,48] and adverse effects were being identified through moni-toring in three studies [33,41,46]. Treatment of patients was adapted according to the principles of stepped care in eleven studies [34–37,39–41,44,47,48,51].

Evidence-based treatment was provided in all studies. The majority of studies provided pa-tients in the collaborative care group with antidepressant pharmacotherapy [33,34,36,37,39– 46,49–51]. Further evidence-based treatments used in the studies were psychoeducation [33, 34,37–40,42,43,45,46,49,51], psychotherapy (e.g. cognitive behavior therapy) [35,36,40, 42–45,47–50], counseling [34,35,40,41,44–47,49,51] and problem-solving treatment [36– 39,44,48,49].

All but two studies used patients with usual care as control group. One study presented pa-tients in the control group with depression educational pamphlets and community service re-source lists additionally to usual care [37]. The control group patients in another study were advised to consult with their primary physician to receive care for depression beyond usual care [38].

Ten studies reported cost adjustment by usage of reference unit prices for a certain year [35–37,40–43,48,50,51] and three studies stated that there was no need to discount cost data because of a short follow-up [33,34,47].

Quality and risk of bias assessment

Between 42% and 89% of the CHEC-list criteria [28] were fulfilled by the studies. The mean quality criteria fulfillment was 69%. Four studies [33,35,36,47] were able to address almost all methodological quality criteria from the CHEC-list, two studies [45,49] failed to address the majority of these quality criteria. Results of quality assessment based on the CHEC-list are pre-sented inS1 Table.

proportion of missing cost data, randomization imbalances or crossover, appeared in nine studies [35–37,39,43–45,49,51]. Results for the authors' judgments on risk of bias items for each included study and for each risk of bias item as percentages across all included studies are presented inS1andS2Figs.

Effects

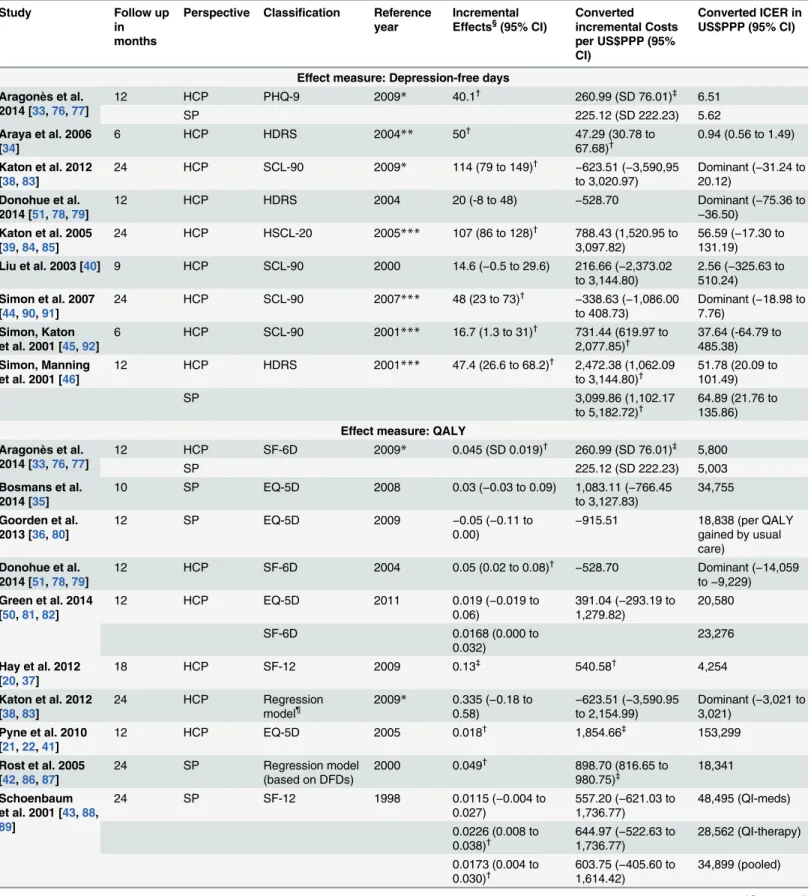

Depression-free days. More than half of the studies reported incremental DFDs [34,38–

40,44–46] or, both, DFDs and QALYs [33,42,51]. The studies which reported DFDs as their primary effect measure calculated them using the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HDRS) [34,46,51], the 20-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale (HSCL-20) [39], the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [33], or the Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) [38,40,44,46]. The study by Rost et al. [42] used directly reported depression impairment-free days. For a follow-up period of less than twelve months, the lowest/highest reported effects were 14.6 [40] and 50 [34] incremental DFDs, respectively. For a follow-up of twelve months (24 months) the lowest/highest reported effects were 20 [51] and 47.4 [46] (48 [44] and 107 [39]) incremental DFDs, respectively. In two studies with DFDs as effect measure, the incre-mental effect was not statistically significant [40,51]. The main findings concerning the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care vs. usual care of the included studies are summarized in Table 2.

QALYs. QALYs were reported by more than half of the studies [33,35–38,41–43,47,51].

Both [47,50] or either the EQ-5D [33,36,41] and the Short Form Health Survey (SF-12/SF-6D) [33,37,43,51] were used to calculate QALYs. Two studies generated QALYs based on age, gender plus clinical measures [38] and DFDs [42], respectively, using a regression model. For a follow-up of ten to twelve months (18 to 24 months), the lowest positive effect was 0.008 [47] (0.0115 [43]) additional QALYs and the highest effect was 0.05 [51] (0.335 [38]). Two studies found incremental QALYs for usual care compared to collaborative care of 0.05 [36] and 0.021 [47], respectively. In four studies with QALYs as effect measure, the incremental effect was not statistically significant [35,36,49,50].

Other effects. One study, which examined the preventive effect of stepped collaborative

care for people at risk for depression and anxiety disorders, reported a probability of a depres-sion/anxiety-free year of 0.88 in the collaborative care group and of 0.76 in the usual care group, respectively, leading on to an incremental effectiveness of 0.12. [48]. In another study, which examined the improvement in major depression status through collaborative care based on two clinical trials, 30.6% [13] and 28.1% [52], respectively, more patients in the collaborative care group improved compared to patients with usual care [49]. However, no statistical signifi-cance testing was reported for incremental effectiveness.

Costs

Direct costs. All but two studies included medication and outpatient care costs. The

stud-ies of Green et al. [50] and Donohue et al. [51] excluded medication costs due to difficultstud-ies in data collection. Some studies also considered inpatient care costs [33,35,37–39,41,45,46,50, 51] and non-medical and paramedical costs [36,47,48,50]. Of all studies, 76% reported posi-tive incremental direct costs of collaboraposi-tive care with a range between US$PPP 46 [34] to 3,761 [41]. Negative incremental direct costs were reported with a range between US$PPP

−529 [51] to−982 [44] in favor of the collaborative care group. However, twelve studies either

Table 2. Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care vs. usual care.

Study Follow up

in months

Perspective Classification Reference year

Incremental

Effects§(95% CI) Convertedincremental Costs

per US$PPP (95% CI)

Converted ICER in US$PPP (95% CI)

Effect measure: Depression-free days Aragonès et al.

2014 [33,76,77]

12 HCP PHQ-9 2009* 40.1†

260.99 (SD 76.01)‡

6.51

SP 225.12 (SD 222.23) 5.62

Araya et al. 2006 [34]

6 HCP HDRS 2004** 50†

47.29 (30.78 to

67.68)† 0.94 (0.56 to 1.49) Katon et al. 2012

[38,83]

24 HCP SCL-90 2009* 114 (79 to 149)†

−623.51 (−3,590,95 to 3,020.97)

Dominant (−31.24 to 20.12)

Donohue et al. 2014 [51,78,79]

12 HCP HDRS 2004 20 (-8 to 48) −528.70 Dominant (−75.36 to

−36.50)

Katon et al. 2005 [39,84,85]

24 HCP HSCL-20 2005*** 107 (86 to 128)†

788.43 (1,520.95 to 3,097.82)

56.59 (−17.30 to 131.19)

Liu et al. 2003 [40] 9 HCP SCL-90 2000 14.6 (−0.5 to 29.6) 216.66 (−2,373.02

to 3,144.80)

2.56 (−325.63 to 510.24)

Simon et al. 2007 [44,90,91]

24 HCP SCL-90 2007*** 48 (23 to 73)†

−338.63 (−1,086.00 to 408.73)

Dominant (−18.98 to 7.76)

Simon, Katon et al. 2001 [45,92]

6 HCP SCL-90 2001*** 16.7 (1.3 to 31)†

731.44 (619.97 to

2,077.85)† 37.64 (-64.79 to

485.38)

Simon, Manning et al. 2001 [46]

12 HCP HDRS 2001*** 47.4 (26.6 to 68.2)†

2,472.38 (1,062.09

to 3,144.80)† 51.78 (20.09 to

101.49)

SP 3,099.86 (1,102.17

to 5,182.72)† 64.89 (21.76 to

135.86)

Effect measure: QALY Aragonès et al.

2014 [33,76,77]

12 HCP SF-6D 2009* 0.045 (SD 0.019)† 260.99 (SD 76.01)‡ 5,800

SP 225.12 (SD 222.23) 5,003

Bosmans et al. 2014 [35]

10 SP EQ-5D 2008 0.03 (−0.03 to 0.09) 1,083.11 (−766.45

to 3,127.83)

34,755

Goorden et al. 2013 [36,80]

12 SP EQ-5D 2009 −0.05 (−0.11 to

0.00) −

915.51 18,838 (per QALY gained by usual care)

Donohue et al. 2014 [51,78,79]

12 HCP SF-6D 2004 0.05 (0.02 to 0.08)†

−528.70 Dominant (−14,059 to−9,229)

Green et al. 2014 [50,81,82]

12 HCP EQ-5D 2011 0.019 (−0.019 to

0.06)

391.04 (−293.19 to 1,279.82)

20,580

SF-6D 0.0168 (0.000 to

0.032)

23,276

Hay et al. 2012 [20,37]

18 HCP SF-12 2009 0.13‡

540.58†

4,254

Katon et al. 2012 [38,83]

24 HCP Regression

model¶ 2009* 0.335 (0.58) −0.18 to to 2,154.99)−623.51 (−3,590.95 Dominant (3,021) −3,021 to Pyne et al. 2010

[21,22,41]

12 HCP EQ-5D 2005 0.018†

1,854.66‡

153,299

Rost et al. 2005 [42,86,87]

24 SP Regression model

(based on DFDs)

2000 0.049†

898.70 (816.65 to 980.75)‡

18,341

Schoenbaum et al. 2001 [43,88,

89]

24 SP SF-12 1998 0.0115 (−0.004 to

0.027)

557.20 (−621.03 to 1,736.77)

48,495 (QI-meds)

0.0226 (0.008 to 0.038)†

644.97 (−522.63 to 1,736.77)

28,562 (QI-therapy)

0.0173 (0.004 to 0.030)†

603.75 (−405.60 to 1,614.42)

34,899 (pooled)

The mean intervention cost of all studies ranged between US$PPP 90 [33] to 1,269 [38], ex-cept for the study by Araya et al. [34] which reported intervention costs of only US$PPP 19. The intervention components ranged from only additional individual consultations from care managers [33,36,46,47,49] to complex (stepped) collaborative care interventions [34,35,38, 39,43,48,51]. A detailed description of the intervention costs is given inS3 Table.

Indirect costs. Aragonès et al. [33] reported mean indirect costs of temporary disability

leave from work amounting to US$PPP 899 (930) in the collaborative care group (usual care group). The mean productivity costs as reported by Goorden et al. [36] were US$PPP 14,920 (17,158). These costs consisted of US$PPP 1,988 (2,441) for absenteeism and US$PPP 13,065 (15,947) for presenteeism, respectively [36]. Three studies interpreted patient time and travel costs as indirect costs [36,37,41], and one of these studies only indicated that they ascertained indirect costs for their economic evaluation but did not report them separately [37].

Table 2. (Continued)

Study Follow up

in months

Perspective Classification Reference year

Incremental Effects§(95% CI)

Converted incremental Costs per US$PPP (95% CI)

Converted ICER in US$PPP (95% CI)

van der Weele et al. 2012 [47]

12 SP SF-12 2001* 0.008 6,996.50 874,562 (age 75–80)

0.02 −859.59 Dominant (age80)

EQ-5D 2001* −0.021 6,996.50 Dominated (age 75–

80)

0.044 −859.59 Dominant (age80)

Other effect measures van't

Veer-Tazelaar et al. 2010 [48,93]

12 SP Depression-/

anxiety-free year

2007 0.12 (0.01 to 0.24)†

probability for a beneficial outcome

702.87 5,677 (−1,175 to 35,774) per depression/anxiety-free year

Von Korff et al.

1998 [13,49,52]& 7 HCP Successfullytreated case (SCL-90)

1995*** 30.6% successfully treated cases of major depression

677.64 2,215 per

successfully treated case of major depression 1996*** 28.1% successfully

treated cases of major depression

497.39 1,284 per

successfully treated case of major depression HCP = Health Care Perspective; SP = Societal Perspective; DFD = Depression-free day; QALY = Quality-adjusted life year; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; HDRS = Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; SCL-90 = Symptom Checklist-90; HSCL-20 = 20-item Hopkins Symptom Checklist Depression Scale; SF-12 = 12-Item Short Form Health Survey; CLP = Chilean Pesos; ICER = Incremental Cost-Effectiveness Ratio; QI-meds = quality improvement—medical management; QI-therapy = quality improvement—psychotherapy

&Analysis was based on two RCT §Based on follow up in months

¶QALYs were estimated based on age, sex, microalbuminuria, HbA

1c, LDL-C and systolic blood pressure levels

*Based on the middle of the follow up period **Based on the year of article receipt by journal ***Based on the publication year

†signi

ficant with p<0.05

‡signi

ficant with p<0.00

Cost-effectiveness

Cost-effectiveness per depression-free day. All but three studies with DFDs as effect

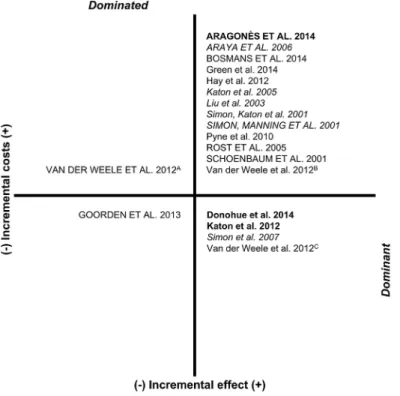

mea-sure reported that collaborative care is more effective in terms of additional DFD, but also more expensive [33,34,39,40,45,46]. From a health care perspective, ICERs ranged from dominance [38,44,51] to US$PPP 56.59 [39] per additional DFD. From a societal perspective, the ICERs ranged from US$PPP 5.62 [33] to 64.89 [46] per additional DFD. The directions of the differences in costs and depression free days (and QALYs) are summarized in a cost-effec-tiveness plane (Fig 2).

Cost-effectiveness per QALY. The majority of studies with QALYs as effect measure

re-ported that collaborative care is more effective in terms of additional QALYs, but also more ex-pensive [33,35–37,41–43,47,50] (Fig 2). From a health care perspective, ICERs ranged from dominance [38,51] to US$PPP 153,299 [41] per additional QALY. From a societal perspective, ICERs ranged from dominance [47] to US$PPP 874,562 [47] per additional QALY. The study by van der Weele et al. [47] reported that collaborative care dominated usual care in patients aged>80 years, but was dominated by usual care in patients aged 75 to 80 years. The study by Goorden et al. [36] found higher costs and higher effects for usual care compared to collabora-tive care, with an ICER of US$PPP 18,838 per additional QALY.

Cost-effectiveness per other outcome. One study of stepped collaborative care for people

aged75 at risk for depression and anxiety disorders indicated that collaborative care is more effective in terms of preventing depression/anxiety disorders but also more expensive com-pared to usual care [48]. The ICER was US$PPP 5,677 per depression/anxiety-free year. Anoth-er study indicated that collaborative care for depressed primary care patients is more effective Fig 2. Cost effectiveness plane for studies with costs per DFD/QALY.In capitals: studies with a societal perspective, in italics: studies with costs per DFD, in bold: studies with costs per DFD and QALY,APatients

aged 75–80, effectiveness measurement instrument EQ-5D;BPatients aged 75–80, effectiveness

in terms of successfully treated cases but also more expensive compared to usual care [49]. Based on two clinical trials, the ICER was US$PPP 2,215 (1,284) per case successfully treated. Neither of these two studies reported, both, a significant incremental effect and significant incremental costs.

Discussion

This study reports a systematic review of cost-effectiveness analyses of (stepped) collaborative care compared with usual care for the treatment of patients with depressive disorders in prima-ry care. In 13 of the 19 included studies, collaborative care was associated with better effects and higher costs (Fig 2). Across the studies showing a higher effectiveness in terms of addition-al QALYs, collaborative care was associated with ICERs ranging from dominance to US$PPP 153,299 from a health care perspective and from dominance to US$PPP 874,562 from a societal perspective. Across the studies showing a higher effectiveness in terms of additional DFD, col-laborative care was associated with ICERs ranging from dominance to US$PPP 56.59 from a health care perspective and from US$PPP 5.62 to 64.89 from a societal perspective.

Compared with incremental costs per additional QALY for collaborative care reported in the review by van Steenbergen-Weijenburg et al. [18] (US$ 21,478 to 49,500), the current range is considerably broader. All three studies with dominant ICERs used a health care perspective, had a follow-up period of twelve to 24 months and were conducted in populations of depres-sive patients with comorbid diseases or patients with post-surgery depression, respectively [38, 44,51]. Yet, the study by Katon et al. [38] estimated QALYs based on a regression model and the ICER showed a wide confidence interval. The ICER of the study by Pyne et al. [41] (US $PPP 153,299), which exceeded the frequently applied cost-effectiveness threshold of US$ 50,000 per additional QALY [53], resulted from high costs and modest effectiveness of collabo-rative care. The ICER of the study by van der Weele et al. [47] (US$PPP 874,562 for patients aged 75–80) resulted from a very small and non-significant effectiveness of collaborative care.

Across all studies included in this review, the time horizons of the economic evaluations as well as the inclusion of indirect costs in the cost calculation varied considerably. Studies with time horizons of more than one year had incremental costs per QALY gained ranging from dominance to US$PPP 34,899, studies with time horizons of one year and below had incremen-tal costs per QALY gained ranging from dominance to US$PPP 874,562. There might be a trend showing better ICERs in studies with longer time horizons. Yet, ICERs may be influenced not only by the time horizons but also by the intervention elements, the included cost elements (e.g. inpatient costs, medication costs) and the size of health effects. In fact, the range of health effect sizes in studies with time horizons of more than one year was 0.0173 to 0.335 incremental QALYs, and in studies with time horizons one year and below it was−0.05 to 0.05 incremental

QALYs. According to the American Psychiatric Association [12], the average duration of MDD is between 16 to 24 weeks. However, MDD is recurrent in around 40% of patients within two years and unremitting in at least 15%, leading to persistent residual symptoms and social or occupational impairment [12,54,55]. Around 5% to 10% of patients have a continuous MDD for 2 or more years, illustrating the high risk of chronification [8]. Therefore, time hori-zons of at least one to two years would be desirable, despite the high costs of clinical trials with a long follow-up.

costs of patients with depression [7,56,57]. However, there is an ongoing debate on whether to include indirect costs in economic evaluations [58,59] and various national guidelines for economic evaluations mainly recommend a health care payer’s perspective [60–63].

Methodological quality varied across studies. The range of scores on the 19-item CHEC-list [28] was from eight to 17 points. Notably, the quality of the included studies improved over time. Studies published before 2009 (47%) had a mean score of 12 points and studies published after 2009 (53%) had mean score of 15 points. Seven studies reported neither significant incre-mental effects nor significant increincre-mental costs, possibly attributable to an insufficient sample size [35,36,40,47,49–51]. Two studies themselves indicated that their cost-effectiveness anal-yses were underpowered [35,49], which is a common problem of economic evaluations con-ducted alongside clinical trials [64–66]. In order to further improve quality of economic evaluations it is suggested to conduct cost-effectiveness analyses based on samples large enough to be confident in the resulting cost-effectiveness estimates [67], as it is anticipated in the study embedded in the intersectoral research network“psychenet: Hamburg Network for Mental Health (2011–2014)”[68].

The QALY valuation methods used across studies were mainly based on utility scales such as EQ-5D or SF-6D. Two studies estimated QALYs based on regression models with DFD or clinical measures as independent variables [38,42]. According to Jonkers et al. [69] utility scales should be preferred for cost-utility analyses to estimate health effects of quality improve-ments for depression, compared with QALYs derived from DFD. Moreover, a direct compari-son between those QALYs should be avoided [69].

It cannot be ruled out that cost-effectiveness analyses conducted alongside randomized con-trolled trials of the effect of collaborative care for the treatment of depressive disorders in pri-mary care remain unpublished [70]. Therefore, reporting bias may occur. Yet, it is beyond the scope of this study to examine the retention of cost-effectiveness data to the public. However, there appears to be a strong relationship between the strength and direction of effectiveness re-sults and the presence of a concurrent economic evaluation [70], leading to a potential overesti-mation of cost-effectiveness of collaborative care compared with usual care. In order to prevent reporting bias, cost-effectiveness analyses should be guided by priorly published study proto-cols [71].

Generalizability and comparability of the studies included in this review is debatable due to methodological differences and heterogeneous general characteristics. Among others, the study perspectives, settings and effect measures used varied significantly between the studies. For in-stance, the differences in study perspectives may have led to differences in identification and measurement of costs across studies, since, from a health care perspective, a more restricted se-lection of cost elements is likely. The settings of the studies were mainly primary care clinics or practices, yet in four different countries. Health care system characteristics across countries of studies included in this review are expected to differ markedly. In addition, nearly half of all studies only included female or elderly patients and patients with co-morbidities, respectively, which are also factors potentially affecting generalizability [72]. In order to improve generaliz-ability, PPP were used in this review to adjust for price level differences across countries [72, 73]. This approach clearly improved comparability across studies. However, it is still a gross adjustment and not a reflection of differences in health care system, unit prices or care provider characteristics between countries [72,74].

Limitations of this study

care groups. Second, the cost-effectiveness of collaborative care compared with usual care was potentially overestimated due to publication bias. Third, the heterogeneity of interventions may have influenced the variation of ICERs as complexity and diversity of collaborative care el-ements varied across studies. Fourth, the variation of cost categories included in the analyses was considerable. Fifth, the majority of the studies were conducted in the USA. Generalizability to health care systems outside the USA may be limited, because cost-effectiveness of collabora-tive care may vary across populations and health insurance systems. Last, the review was limit-ed to publishlimit-ed studies in English or German, thus potentially introducing bias in the selection of publications.

Conclusion

Despite our review improved the comparability of study results, cost-effectiveness of collabora-tive care compared with usual care for the treatment of patients with depressive disorders in primary care is ambiguous depending on willingness to pay for an additional QALY or DFD, respectively. There remains considerable uncertainty due to inconsistent results among includ-ed studies. Reviewinclud-ed cost-effectiveness analyses differinclud-ed considerably in terms of economic quality, and risk of bias remained uncertain in the majority of studies, due to insufficient re-porting. Future cost-effectiveness analyses using QALYs as summary measures and a time ho-rizon of at least one year are needed in order to improve decision-making. Such studies should be conducted in large and representative patient samples from a societal perspective, taking into account indirect costs.

Supporting Information

S1 PRISMA Checklist. PRISMA Checklist [75].

(DOC)

S1 Fig. Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for

each included study.+: low risk of bias.−: high risk of bias.?: unclear of risk of bias. Other bias:

randomization imbalances (Hay 2012; Schoenbaum 2001; Simon, Katon 2001; Simon 2007), underpowered analysis (Bosmans 2014; Katon 2005; Von Korff 1998), high proportion of miss-ing cost-data (Donohue 2014; Katon 2004), crossmiss-ing-over (Goorden 2013).

(TIFF)

S2 Fig. Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

(TIFF)

S1 Table. Methodological quality of studies’economic evaluations.CHEC-list items: Study

population, competing alternatives, research question, economic study design, time horizon, perspective, identification of costs, cost measurement cost valuation, outcome identification, outcome measurement, incremental analysis, discounting, sensitivity analysis, conclusion, gen-eralizability, conflict of interest, ethical issues.

(DOCX)

S2 Table. Direct cost elements and mean costs.IG = Intervention Group, CLP = Chilean

Pesos,§Analysis was based on two RCT,

Total healthcare costs,

Total societal costs,& signifi-cant with p<0.05,†significant with p<0.001.

S3 Table. Intervention elements and mean costs.CLP = Chilean Pesos,§Analysis was based on two RCT.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant numbers: 01KQ1002B, 01GY1142 and 01GY55A) within the projects“psychenet: Hamburg Network for Mental Health”,“GermanIMPACT”and“AgeMooDe”, and by the Federal Minis-try of Health (grant number: II A 5–2513 FSB 014) within the project“AgeMooDe-Synergie”. Psychenet is a project for which the City of Hamburg was given the title“Health Region of the Future”in 2010. The aim of the project is to promote mental health today and in the future, and to achieve an early diagnosis of and effective treatment for mental illnesses. Further infor-mation and a list of all project partners can be found atwww.psychenet.de.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: TG CB AW BW SRH MH HHK. Analyzed the data: TG AW CB. Wrote the paper: TG CB HHK.

References

1. Ferrari AJ, Charlson FJ, Norman RE, Patten SB, Freedman G, Murray CJL, et al. (2013) Burden of De-pressive Disorders by Country, Sex, Age, and Year: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. PLoS Med 10. Available:http://www.plosmedicine.org/article/fetchObject.action?uri = info% 3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pmed.1001547. Accessed 25 April 2014.

2. The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, et al. (2004) Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109: 21–27. doi:10. 1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00327.x

3. The ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, Bruffaerts R, Brugha TS, et al. (2004) 12-Month comorbidity patterns and associated factors in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand 109: 28–37. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00328.x

4. Busch MA, Maske UE, Ryl L, Schlack R, Hapke U (2013) Prevalence of depressive symptoms and di-agnosed depression among adults in Germany. Results of the German Health Interview and Examina-tion Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz 56: 733–739. doi:10.1007/s00103-013-1688-3PMID:23703492

5. Jacobi F, Wittchen H-U, Holting C, Hofler M, Pfister H, Müller N, et al. (2004) Prevalence, co-morbidity and correlates of mental disorders in the general population: results from the German Health Interview and Examination Survey (GHS). Psychol Med 34: 597–611. doi:10.1017/S0033291703001399PMID: 15099415

6. Olesen J, Gustavsson A, Svensson M, Wittchen H-U, Jönsson B, The CDBE study group, et al. (2012) The economic cost of brain disorders in Europe. Eur J Neurol 19: 155–162. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331. 2011.03590.xPMID:22175760

7. Luppa M, Heinrich S, Angermeyer MC, König H-H, Riedel-Heller SG (2007) Cost-of-illness studies of depression. A systematic review. J Affect Disord 98: 29–43. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.017PMID: 16952399

8. American Psychiatric Association (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 943 p.

9. Coryell W, Endicott J, Winokur G, Akiskal H, Solomon D, Leon A, et al. (1995) Characteristics and Sig-nificance of Untreated Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 152: 1124–1129. PMID:7625458

11. Härter M, Klesse C, Bermejo I, Schneider F, Berger M (2010) Unipolar Depression. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Recommendations From the Current S3/National Clinical Practice Guideline. Dtsch Arz-tebl Int 107: 700–708. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0700PMID:21031129

12. American Psychiatric Association (2010) Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Arlington (VA): American Psychiatric Association. 152 p. Available:http:// psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1667485. Accessed 29 April 2014.

13. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Walker E, Simon GE, Bush T, et al. (1995) Collaborative Management to Achieve Treatment Guidelines. Impact on Depression in Primary Care. JAMA 273: 1026–1031. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520370068039PMID:7897786

14. Barkil-Oteo A (2013) Collaborative Care for Depression in Primary Care: How Psychiatry Could“ Trou-bleshoot”Current Treatments and Practices. Yale J Biol Med 86: 139–146. PMID:23766735

15. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, Lovell K, Richards D, Gask L, et al. (2012) Collaborative care for depres-sion and anxiety problems (Review). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Available:http:// onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD006525.pub2/abstract. Accessed 30 April 2014.

16. Baumeister H, Hutter N (2012) Collaborative care for depression in medically ill patients. Curr Opin Psy-chiatry 25: 405–414. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283556c63PMID:22801356

17. Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J and Sutton A (2006) Collaborative care for depression in primary care: Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry 189: 484–493. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.023655PMID:17139031

18. van Steenbergen-Weijenburg KM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Horn EK, van Marwijk HWJ, Beekman ATF, Rutten FFH, et al. (2010) Cost-effectiveness of collaborative care for the treatment of major de-pressive disorder in primary care. A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 10: 19. Available:http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2826303/pdf/1472-6963-10-19.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2014. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-10-19PMID:20082727

19. van der Weele GM, de Waal MWM, van den Hout WB, van der Mast RC, de Craen AJM, Assendelft WJJ, et al. (2011) Yield and costs of direct and stepped screening for depressive symptoms in subjects aged 75 years and over in general practice. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 26: 229–238. doi:10.1002/gps. 2518PMID:20665554

20. Ell K, Katon W, Xie B, Lee P-J, Kapetanovic S, Guterman J, et al. (2010) Collaborative Care Manage-ment of Major Depression Among Low-Income, Predominantly Hispanic Subjects With Diabetes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 33: 706–713. doi:10.2337/dc09-1711PMID:20097780

21. Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, Robinson DE, Mittal D, Henderson KL (2006) Design and implemen-tation of the Telemedicine-Enhanced Antidepressant Management Study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 28: 18–26. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.001PMID:16377361

22. Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, Williams DK, Robinson DE, Mittal D, et al. (2007) A Randomized Trial of Telemedicine-Based Collaborative Care for Depression. J Gen Intern Med 22: 1086–1093. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0201-9PMID:17492326

23. Sampson M, Shojania KG, Garritty C, Horsley T, Ocampo M, Moher D (2008) Systematic reviews can be produced and published faster. J Clin Epidemiol 61: 531–536. doi:10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.02.004 PMID:18471656

24. Gunn J, Diggens J, Hegarty K, Blashki G (2006) A systematic review of complex system interventions designed to increase recovery from depression in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res 6: 88. Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1559684/pdf/1472-6963-6-88.pdf. Accessed 02 Febru-ary 2015. PMID:16842629

25. Katon W, Russo J, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Bush T, et al. (2002) Long-term Effects of a Collabora-tive Care Intervention in Persistently Depressed Primary Care Patients. J Gen Intern Med 17: 741–

748. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1495114/pdf/jgi_11051.pdf. Accessed 06 October 2014. PMID:12390549

26. Meeuwissen JAC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, van Marwijk HWJ, Rijnders PBM, Donker MCH (2008) A stepped care programme for depression management: an uncontrolled pre-post study in primary and secondary care in The Netherlands. Int J Integr Care 8: e05. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ pmc/articles/PMC2254490/. Accessed 08 December 2014. PMID:18317562

27. Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Chichester (UK), Hoboken (NJ): The Cochrane Collaboration. 649 p. Available:www.cochrane-handbook.org. Ac-cessed 27 March 2014.

28. Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A (2005) Criteria list for assessment of methodo-logical quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 21: 240–245. doi:10.1017.S0266462305050324PMID:15921065

30. The World Bank (2013) World Development Indicators: Size of the economy. Database: The World Bank.http://wdi.worldbank.org/table/1.1#. Accessed 09 April 2014.

31. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, Carswell C, Moher D, Greenberg D, et al. (2013) Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—Explanation and Elaboration: A Report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force. Value Health 16: 231–250. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002PMID:23538175

32. Mathes T, Walgenbach M, Antoine S-L, Pieper D, Eikermann M (2014) Methods for Systematic Re-views of Health Economic Evaluations: A Systematic Review, Comparison, and Synthesis of Method Literature. Med Decis Making. Available:http://mdm.sagepub.com/content/early/2014/04/08/ 0272989X14526470. Accessed 14 May 2014.

33. Aragonès E, López-Cortacans G, Sánchez-Iriso E, Piñol J-L, Caballero A, Salvador-Carulla L, et al.

(2014) Cost-effectiveness analysis of a collaborative care programme for depression in primary care. J Affect Disord 159: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.021PMID:24679395

34. Araya R, Flynn T, Rojas G, Fritsch R, Simon G (2006) Cost-Effectiveness of a Primary Care Treatment Program for Depression in Low-Income Women in Santiago, Chile. Am J Psychiatry 163: 1379–1387. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.8.1379PMID:16877650

35. Bosmans JE, Dozeman E, van Marwijk HWJ, van Schaik DJF, Stek ML, Beekman ATF, et al. (2014) Cost-effectiveness of a stepped care programme to prevent depression and anxiety in residents in homes for the older people: A randomised controlled trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 29: 182–190. doi:10. 1002/gps.3987PMID:23765874

36. Goorden M, Vlasveld MC, Anema JR, van Mechelen W, Beekman ATF, Hoedeman R, et al. (2013) Cost-Utility Analysis of a Collaborative Care Intervention for Major Depressive Disorder in an Occupa-tional Healthcare Setting. J Occup Rehabil. Available:http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007% 2Fs10926-013-9483-4. Accessed 03 April 2014.

37. Hay JW, Katon WJ, Ell K, Lee P-J, Guterman JJ (2012) Cost-effectiveness analysis of collaborative care management of major depression among low-income, predominantly Hispanics with diabetes. Value Health 15: 249–254. doi:10.1016/j.jval.2011.09.008PMID:22433755

38. Katon W, Russo J, Lin EHB, Schmittdiel J, Ciechanowski P, Ludman E, et al. () Cost-effectiveness of a Multicondition collaborative Care Intervention: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 69: 506–514. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.1548PMID:22566583

39. Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan M-Y, Callahan CM, Williams J Jr., Hunkeler E, et al. (2005) Cost-effec-tiveness of Improving Primary Care Treatment of Late-Life Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62: 1313–1320. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.12.1313PMID:16330719

40. Liu C-F, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, Heagerty P, Felker B, Hasenberg N, et al. (2003) Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Care for Depression in a Primary Care Veteran Population. Psychiatr Serv 54: 698–

704. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.5.698PMID:12719501

41. Pyne JM, Fortney JC, Tripathi SP, Maciejewski ML, Edlund MJ, Williams DK (2010) Cost-effectiveness Analysis of a Rural Telemedicine Collaborative Care Intervention for Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 67: 812–821. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.82PMID:20679589

42. Rost K, Pyne JM, Dickinson LM, LoSasso AT (2005) Cost-Effectiveness of Enhancing Primary Care Depression Management on an Ongoing Basis. Ann Fam Med 3: 7–14. doi:10.1370/afm.256PMID: 15671185

43. Schoenbaum M, Unützer J, Sherbourne C, Duan N, Rubenstein LV, Miranda J, et al. (2001) Cost-effec-tiveness of Practice-Initiated Quality Improvement for Depression: Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 286: 1325–1330. doi:10.1001/jama.286.11.1325PMID:11560537

44. Simon GE, Katon WJ, Lin EHB, Rutter C, Manning WG, Von Korff M, et al. (2007) Cost-effectiveness of Systematic Depression Treatment Among People With Diabetes Mellitus. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64: 65–72. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.64.1.65PMID:17199056

45. Simon GE, Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Unützer J, Lin EHB, Walker EA, et al. (2001) Cost-Effectiveness of a Collaborative Care Program for Primary Care Patients With Persistent Depression. Am J Psychiatry 158: 1638–1644. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1638PMID:11578996

46. Simon GE, Manning WG, Katzelnick DJ, Pearson SD, Henk HJ, Helstad CS (2001) Cost-effectiveness of Systematic Depression Treatment for High Utilizers of General Medical Care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 58: 181–187. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.58.2.181PMID:11177120

48. van't Veer-Tazelaar P, Smit F, van Hout H, van Oppen P, van der Horst H, Beekman A, et al. (2010) Cost-effectiveness of a stepped care intervention to prevent depression and anxiety in late life: rando-mised trial. Br J Psychiatry 196: 319–325. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.109.069617PMID:20357310

49. Von Korff M, Katon W, Bush T, Lin EHB, Simon GE, Saunders K, et al. (1998) Treatment Costs, Cost Offset, and Cost-Effectiveness of Collaborative Management of Depression. Psychosom Med 60: 143–149. PMID:9560861

50. Green C, Richards DA, Hill JJ, Gask L, Lovell K, Chew-Graham C, et al. () Cost-effectiveness of collab-orative care for depression in UK primary care: economic evaluation of a randomised controlled trial (CADET). PLoS One 9: e104225. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4133193/ pdf/pone.0104225.pdf. Accessed 02 Feb 2015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0104225PMID:25121991

51. Donohue JM, Belnap BH, Men A, He F, Roberts MS, Schulberg HC, et al. (2014) Twelve-month cost-ef-fectiveness of telephone-delivered collaborative care for treating depression following CABG surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 36: 453–459. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014. 05.012PMID:24973911

52. Katon W, Robinson P, Von Korff M, Lin E, Bush T, Ludman E, et al. (1996) A Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Treatment of Depression in Primary Care. Arch Gen Psychiatry 53: 924–932. doi:10.1001/ archpsyc.1996.01830100072009PMID:8857869

53. Glied S, Herzog K, Frank R (2010) Review: The Net Benefits of Depression Management in Primary Care. Med Care Res Rev 67: 251–274. doi:10.1177/1077558709356357PMID:20093400

54. Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee HB, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P (2008) Population-Based Study of First Onset and Chronicity in Major Depressive Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 513–520. doi:10.1001/ archpsyc.65.5.513PMID:18458203

55. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, Mueller TI, Lavori PW, Shea MT, et al. (2000) Multiple Recurrences of Major Depressive Disorder. Am J Psychiatry 157: 229–233. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.229PMID: 10671391

56. Wang PS, Simon G, Kessler RC (2003) The economic burden of depression and the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 12: 22–33. doi:10.1002/mpr.139PMID:12830307

57. Wang PS, Patrick A, Avorn J, Azocar F, Ludman E, McCulloch J, et al. (2006) The Costs and Benefits of Enhanced Depression Care to Employers. Arch Gen Psychiatry 63: 1345–1353. doi:10.1001/ archpsyc.63.12.1345PMID:17146009

58. Grima DT, Bernard LM, Dunn ES, McFarlane PA, Mendelssohn DC (2012) Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Therapies for Chronic Kidney Disease Patients on Dialysis: A Case for Excluding Dialysis Costs. Pharmacoeconomics 30: 981–989. doi:10.2165/11599390-000000000-00000PMID:22946789

59. van Baal P, Meltzer D, Brouwer W (2013) Pharmacoeconomic Guidelines Should Prescribe Inclusion of Indirect Medical Costs! A Response to Grima et al. Pharmacoeconomics 31: 369–373; discussion 375–376. doi:10.1007/s40273-013-0042-9PMID:23595557

60. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (2009) General Methods for the Assessment of the Relation of Benefits to Costs Colgne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care. Available:https://www.iqwig.de/download/General_Methods_for_the_Assessment_of_the_Relation_ of_Benefits_to_Costs.pdf. Accessed 30 June 2014.

61. Haute Autorité de santé (2012) Choices in Methods for Economic Evaluation. Saint-Denis La Plaine CEDEX, France: Haute Autorité de santé. Available:http://www.has-sante.fr/portail/upload/docs/ application/pdf/2012-10/choices_in_methods_for_economic_evaluation.pdf. Accessed 01 July 2014.

62. Cleemput I, Neyt M, Van de Sande S, Thiry N (2012) Belgian guidelines for economic evaluations and budget impact analyses: second edition. Brussels, Belgium: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre. Available:https://kce.fgov.be/sites/default/files/page_documents/KCE_183C_economic_evaluations_ second_edition_0.pdf. Accessed 01 July 2014.

63. Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (2006) Guidelines for the Economic Evaluation of Health Technologies: Canada. 3rd Edition. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Tech-nologies in Health. Available:http://www.cadth.ca/media/pdf/186_EconomicGuidelines_e.pdf. Ac-cessed 17 October 2014.

64. Briggs A (2000) Economic evaluation and clinical trials: size matters. BMJ 321: 1362–1363. doi:10. 1136/bmj.321.7273.1362PMID:11099268

65. O'Brien BJ, Drummond MF, Labelle RJ, Willan A (1994) In Search of Power and Significance: Issues in the Design and Analysis of Stochastic Cost-Effectiveness Studies in Health Care. Med Care 32: 150–

163. doi:10.2307/3766311PMID:8302107

67. Glick HA (2011) Sample Size and Power for Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (Part 1). Pharmacoeconomics 29: 189–198. doi:10.2165/11585070-000000000-00000PMID:21309615

68. Watzke B, Heddaeus D, Steinmann M, König H-H, Wegscheider K, Schulz H, et al. (2014) Effective-ness and cost-effectiveEffective-ness of a guideline-based stepped care model for patients with depression: study protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial in routine care. BMC Psychiatry 14: 230. doi:10. 1186/s12888-014-0230-yPMID:25182269

69. Jonkers CCM, Lamers F, Evers SMAA, Bosma H, Van Eijk JTM (2010) Cost-utility estimates in depres-sion: does the valuation method matter? J Ment Health Policy Econ 13: 189–197. doi:10.1016/j.jval. 2010.12.004PMID:21368342

70. Gilbody S, Bower P, Sutton AJ (2007) Randomized trials with concurrent economic evaluations re-ported unrepresentatively large clinical effect sizes. J Clin Epidemiol 60: 781–786. doi:10.1016/j. jclinepi.2006.10.014PMID:17606173

71. Ramsey S, Willke R, Briggs A, Brown R, Buxton M, Chawla A, et al. (2005) Good research practices for cost-effectiveness analysis alongside clinical trials: the ISPOR RCT-CEA Task Force report. Value Health 8: 521–533. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.00045.xPMID:16176491

72. Goeree R, Burke N, O'Reilly D, Manca A, Blackhouse G, Tarride J-E (2007) Transferability of economic evaluations: approaches and factors to consider when using results from one geographic area for an-other. Curr Med Res Opin 23: 671–682. doi:10.1185/030079906x167327PMID:17407623

73. Drummond M, Barbieri M, Cook J, Glick HA, Lis J, Malik F, et al. (2009) Transferability of Economic Evaluations Across Jurisdictions: ISPOR Good Research Practices Task Force Report. Value Health 12: 409–418. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4733.2008.00489.xPMID:19900249

74. Welte R, Feenstra T, Jager H, Leidl R (2004) A Decision Chart for Assessing and Improving the Trans-ferability of Economic Evaluation Results Between Countries. Pharmacoeconomics 22: 857–876. doi: 10.2165/00019053-200422130-00004PMID:15329031

75. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The Prisma Group (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6: 6. Available:http:// www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2707599/pdf/pmed.1000097.pdf. Accessed 17 April 2014.

76. Aragonès E, Caballero A, Piñol JL, López-Cortacans G, Badia W, Hernández JM, et al. (2007)

Assess-ment of an enhanced program for depression manageAssess-ment in primary care: a cluster randomized con-trolled trial. The INDI project (Interventions for Depression Improvement). BMC Public Health 7: 253. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-7-253PMID:17883845

77. Aragonès E, López-Cortacans G, Badia W, Hernández JM, Caballero A, Labad A, et al. (2008)

Improv-ing the Role of NursImprov-ing in the Treatment of Depression in Primary Care in Spain. Perspect Psychiatr Care 44: 248–258. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.2008.00184.xPMID:18826463

78. Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Schulberg HC, Reynolds CF 3rd (2009) The Bypassing the Blues treatment protocol: stepped collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression. Psychosom Med 71: 217–230. Available:http://graphics.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/

FPDDNCJCJCGMKK00/fs047/ovft/live/gv024/00006842/00006842-200902000-00010.pdf. Accessed 12 February 2015. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181970c1cPMID:19188529

79. Rollman BL, Belnap BH, LeMenager MS, Mazumdar S, Houck PR, Counihan PJ, et al. (2009) Tele-phone-delivered collaborative care for treating post-CABG depression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 302: 2095–2103. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1670PMID:19918088

80. Vlasveld MC, Anema JR, Beekman ATF, van Mechelen W, Hoedeman R, van Marwijk HWJ, et al. (2008) Multidisciplinary Collaborative Care for Depressive Disorder in the Occupational Health Setting: design of a randomised controlled trial and cost-effectiveness study. BMC Health Serv Res 8. Avail-able:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2390533/pdf/1472-6963-8-99.pdf. Accessed 08 April 2014.

81. Richards DA, Hill JJ, Gask L, Lovell K, Chew-Graham C, Bower P, et al. (2013) Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ 347: f4913. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3746956/pdf/bmj.f4913.pdf. Ac-cessed 02 February 2015. doi:10.1136/bmj.f4913PMID:23959152

82. Richards DA, Hughes-Morley A, Hayes RA, Araya R, Barkham M, Bland JM, et al. (2009) Collaborative Depression Trial (CADET): multi-centre randomised controlled trial of collaborative care for depression

—study protocol. BMC Health Serv Res 9: 188. Available:http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC2770465/pdf/1472-6963-9-188.pdf. Accessed 02 February 2015. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-9-188 PMID:19832996

84. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, Williams JW Jr, Hunkeler E, Harpole L, et al. (2002) Collaborative Care Management of Late-Life Depression in the Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 288: 2836–2845. doi:10.1001/jama.288.22.2836PMID:12472325

85. Unützer J, Katon W, Williams JW Jr., Callahan CM, Harpole L, Hunkeler EM, et al. (2001) Improving Pri-mary Care for Depression in Late Life: The Design of a Multicenter Randomized Trial. Med Care 39: 785–799. PMID:11468498

86. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith JL, Elliott CE, Dickinson M (2002) Managing depression as a chronic disease: a randomised trial of ongoing treatment in primary care. BMJ 325: 934. doi:10.1136/bmj.325.7370.934 PMID:12399343

87. Rost K, Nutting PA, Smith J, Werner JJ (2000) Designing and Implementing a Primary Care Interven-tion Trial to Improve the Quality and Outcome of Care for Major Depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 22: 66–77. doi:10.1016/S0163-8343(00)00059-1PMID:10822094

88. Rubenstein LV, Jackson-Triche M, Unutzer J, Miranda J, Minnium K, Pearson ML, et al. (1999) Evi-dence-based care for depression in managed primary care practices. Health Aff (Millwood) 18: 89–

105. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.89

89. Wells KB, Sherbourne C, Schoenbaum M, Duan N, Meredith LS, Unützer J, et al. (2000) Impact of Dis-seminating Quality Improvement Programs for Depression in Managed Primary Care: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 283: 212–220. doi:10.1001/jama.283.2.212PMID:10634337

90. Katon W, Von Korff M, Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Lin E, Simon G, et al. (2004) Behavioral and Clinical Factors Associated With Depression Among Individuals With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 27: 914–920. PMID:15047648

91. Katon WJ, Von Korff M, Lin E-HB, Simon G, Ludman E, Russo J, et al. (2004) The Pathways Study: A Randomized Trial of Collaborative Care in Patients With Diabetes and Depression. Arch Gen Psychia-try 61: 1042–1049. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.10.1042PMID:15466678

92. Katon W, Von Korff M, Lin E, Simon G, Walker E, Unützer J, et al. (1999) Stepped Collaborative Care for Primary Care Patients With Persistent Symptoms of Depression: A Randomized Trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry 56: 1109–1115. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1109PMID:10591288

![Fig 1. Flow chart of the selection process based on the PRISMA Statement [75].](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/16363625.190450/5.918.299.706.117.577/fig-flow-chart-selection-process-based-prisma-statement.webp)