www.epjournal.net – 2013. 11(5): 965-972

¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯

Original Article

Changes in Women’s Attractiveness Perception of Masculine Men’s Dances

across the Ovulatory Cycle: Preliminary Data

Tessa Cappelle, Department of Biological Personality Psychology and Diagnostics and Courant Research Centre Evolution of Social Behavior, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany.

Bernhard Fink, Department of Biological Personality Psychology and Diagnostics and Courant Research Centre Evolution of Social Behavior, University of Göttingen, Göttingen, Germany. Email:

Abstract: Women’s preferences for putative cues of genetic quality in men's voices, faces, bodies, and behavioral displays are stronger during the fertile phase of the ovulatory cycle. Here we show that ovulatory cycle-related changes in women’s attractiveness perceptions of male features are also found with dance movements, especially those perceived as highly masculine. Dance movements of 79 British men were recorded with an optical motion-capture system whilst dancing to a basic rhythm. Virtual humanoid characters (avatars) were created and converted into 15-second video clips and rated by 37 women on masculinity. Another 23 women judged the attractiveness of the 10 dancers who scored highest and those 10 who scored lowest on masculinity once in days of high fertility and once in days of low fertility of their ovulatory cycle. High-masculine dancers were judged higher on attractiveness around ovulation than on other cycle days, whilst no such perceptual difference was found for low-masculine dancers. We suggest that women may gain fitness benefits from evolved preferences for masculinity cues they obtain from male dance movements.

Keywords: attractiveness, body movement, dance, fertility, ovulatory cycle

¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ Introduction

only around ovulation, as ancestral women might thus have received genetic benefits, while paying costs of extra-pair sex throughout the cycle. Hence, ovulatory cycle-related shifts in female mate preferences appear to reflect a trade-off in choosing mates with “good genes” vs. mates with the willingness to invest in a committed relationship. A recent meta-analysis including the findings of published and unpublished effects reported (i) robust context-dependent ovulatory cycle shifts in women’s mate preferences and (ii) no evidence for a publication bias that could have accounted for these effects (Gildersleeve, Haselton, and Fales, 2013). An ovulatory shift in female preferences was first reported by Penton-Voak et al. (1999) for masculine male faces, particularly when women evaluate them as short-term partners. Similar effects have been found in women’s preferences for masculine male voices (Feinberg et al., 2006; Puts, 2005), masculine male bodies (Little, Jones, and Burriss, 2007), dominant men’s odor (Havlicek, Roberts, and Flegr, 2005), and male behavioral displays (Gangestad, Garver-Apgar, Simpson, and Cousins, 2007; Gangestad, Simpson, Cousins, Garver-Apgar, and Christensen, 2004). However, other studies have found no effect of fertility on masculinity preferences (Harris, 2011; Peters, Simmons, and Rhodes, 2009).

Recent research shows that women also assess aspects of male quality from men’s dance movements. Darwin (1871) suggested that human dance might be a sexually selected display and there is corroborating evidence for the hypothesis that human dance may communicate health, strength, and thus sexual attractiveness (Hanna, 2010). For example, Hugill et al. (2009) showed that women perceive dances of men who are physically strong as attractive and assertive, thus concluding that physical strength is not only conveyed via static representations of male morphology but also via their dance movements. To identify the biomechanical characteristics of “good” male dancers, Neave et al. (2011) had women rate dance quality of virtual characters (avatars) with applied motion-captured dance movements of British men. “Good” dancers were characterized by large and variable movements in relation to bending and twisting movements of their head/neck and torso and these movements were perceived to signal physical strength (McCarty, Hönekopp, Neave, Caplan, and Fink, 2013). Like in many animal species, sexually dimorphic traits in humans (such as strength) may have evolved in response to intra-sexual conflicts, but also in the course of inter-sexual selection (Puts, 2010). Women prefer masculine male features (but see Rhodes, 2006), especially in times of high fertility (see above), and although preliminary evidence exists that this preference extends to dynamic behavioral displays, no study has investigated women’s attractiveness preferences for male dance masculinity across the ovulatory cycle. We predicted that in times of higher fertility, women would judge high-masculine male dancers higher on attractiveness than in times of lower fertility, but no such effect was expected for low-masculine male dancers.

Materials and Methods Stimuli

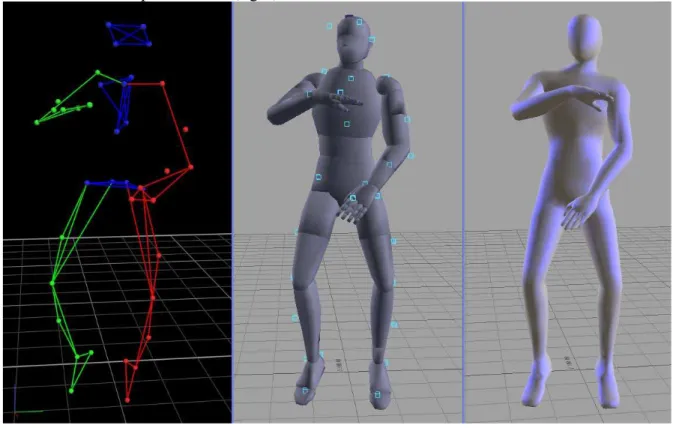

5th finger, and the joints of wrist, elbow, knee and foot, corrected for trait size), height (cm) and weight (kg). Participants were recruited from the student population of Northumbria University (U.K.). Body movements were recorded using a 12-camera optical motion-capture system (Vicon, Oxford). None of the participants was a professional dancer and none reported physical injuries or current health problems that could have affected their movements. Thirty-nine 14 mm retro-reflective markers were attached to each participant in accordance with the Vicon Plug-In-Gait marker set to capture all major body structures. Following calibration, participants danced for 30 seconds to a popular song, of which only the core drumbeat was presented (to eliminate possible music likeability effects). No instruction was given on how they should dance. These motion-capture data were applied to a featureless, gender-neutral humanoid character (avatar), using Autodesk MotionBuilder 2010 (see Figure 1). One participant was excluded at this point, owing to incomplete coordinate data (due to marker detachment or occlusion), thus leaving dance movements of 79 males. These were rendered in the form of 773 x 632 pixels video clips (see also McCarty et al., 2013; Neave et al., 2011).

Figure 1. Snapshots of the creation process of a virtual dance character. The initial stick figure with captured markers (left), application of the motion data to an actor (middle) and the final avatar for presentation (right).

woman judged 40 dancers, randomly selected out of the total set of 79. The videos of the 10 dancers who received the highest ratings (M = 4.78, SD = 0.27) and the 10 dancers who received the lowest ratings (M = 2.19, SD = 0.41) served as stimuli in the main rating study. Mean masculinity ratings of high- and low-masculine dancers differed, t(18) = 16.81, p = 0.001. Tests for differences between high- and low-masculine dancers in body symmetry, height and weight revealed no significant results (body symmetry: t(18)= 0.20, p = 0.85; height: t(18)= 0.24, p = 0.81; weight: t(18) = 0.27, p = 0.79, all p two-tailed).

Rating study

Sixty women aged 20 to 31 years (M = 24.02, SD = 3.13) were recruited from the local student population. All women reported to be heterosexual, were neither pregnant nor breastfeeding, and were not taking hormonal contraceptives or supplements. Each woman was assigned to two test sessions, one on estimated days of higher fertility and one on days of lower fertility using the forward counting method (Wilcox et al., 2001). On both occasions, each woman judged the attractiveness of the 10 high- and the 10 low-masculine dancers on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = “not attractive”; 7 = “very attractive”). The presentation order of video clips was randomized between participants and across test sessions. After completion of the second session, women reported the onset of their next menses to the female investigator. High- and low-fertility days were estimated using the modified backward counting method, which assumes ovulation 14 days prior to the onset of next menses (Schwarz and Hassebrauck, 2008). High-fertility days were defined as the five days before ovulation (including that day) and low-fertility days included the remainder of the cycle (Schwarz and Hassebrauck, 2008; Wilcox, Dunson, Weinberg, Trussell, and Baird, 2001). Finally, all women were debriefed and received 15 Euros for their participation.

Of the initially recruited 60 women, data from 37 women were not considered in the present statistical analyses, as these participants did not complete the study (n = 18) or because the initial assignment to the two test sessions could not be confirmed by the backward counting method (n = 19). Thus, for the final assessment of high- and low-fertility days, we relied on the backward counting method, leaving 23 women aged 20 to 31 years (M = 25.00, SD =3.34) with an average cycle length of 29.59 days (SD = 3.83) for the statistical analyses. Twelve women rated the dancers’ attractiveness first on times of high fertility, and 11 women rated them first on times of low fertility. Difference scores of high- minus low-fertility attractiveness ratings of each woman were calculated for both the high- and low-masculine dancers.

Results

Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests were used to check for normal distribution of the difference scores of attractiveness ratings for low- and high-masculine dancers (both Z < 0.75; both p > 0.63). Table 1 reports descriptive statistics of women’s attractiveness ratings of high- and low-masculine dancers on high- and low-fertility days. Zero-order correlations (Pearson r) of women’s attractiveness ratings of dance videos on days of high- and

(r = 0.53, p = .010, two-tailed) and low-masculine dancers (r = 0.56, p =.006, two-tailed).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (M ± SD) of women’s attractiveness ratings of high- and low masculine dancers on high- and low fertility days.

Ovulatory cycle phase

high fertility low fertility

high masculine 3.63 ± 0.68 3.33 ± 0.67

low masculine 2.87 ± 0.85 2.87 ± 0.80

One-sample t-tests against the value of zero (i.e., the assumption of no differences in attractiveness ratings between the two test sessions) revealed a significant result for high-masculine dancers, but not for low-masculine dancers (high-masculine dancers: t(22) = 2.39, p = 0.013, d = 0.46; low-masculine dancers: t(22) = -0.06, p = 0.478, d = 0.00; both

p one-tailed); i.e., women judged high-masculine dancers to be more attractive on days of high fertility relative to low-fertility days, but this effect was not found for low-masculine dancers.

Discussion

As predicted, women’s attractiveness assessments of masculine men’s dance movements were different on days of high- and low-fertility. This suggests that in addition to previous reports on female preferences for masculine male faces, bodies, voices, and odor at the time of high-fertility, women also exhibit such a preference for male dance movements. The current results are consistent with the results of studies showing an increased preference for men who display social presence and intra-sexual competitiveness on days of high-fertility relative to low-fertility days (Gangestad et al., 2004), and also are consistent with research indicating greater female attraction to masculine walkers around ovulation (Provost, Troje, and Quinsey, 2008). Dance is a universal form of human expression. Unlike other forms of behavioral display, dance requires a complex interplay of physical, cognitive, and aesthetic qualities, and may offer an honest cue to an individual’s quality (Neave et al., 2011). In view of possible relationships of symmetry (a measure of developmental health) with masculinity (Thornhill and Gangestad, 2006) and testosterone response with masculinity (Pound, Penton-Voak, and Surridge, 2009), it is not surprising that fertile women exhibit a preference for masculine male dances.

current research suggests the former, although future studies are needed that specify women’s attractiveness preferences for men’s dances by adding relationship-context (short- vs. long-term) to the assessments of dance quality. That said, we emphasize the preliminary nature of our study, which was designed to provide a first approach to the question on ovulatory cycle-related changes in women’s preference of men’s dance masculinity. It is obvious that high-masculine dancers were judged higher on attractiveness at both high- and low-fertility days, yet an ovulatory cycle shift in attractiveness ratings was observed only for high-masculine dancers and seems to be independent from features such as body symmetry, weight, and height of the dancer. Future studies should aim to identify biomechanical characteristics that constitute dance masculinity and relate this to women’s short-and long-term mate preferences. With reference to the findings of Hugill, Fink, Neave, and Seydel (2009) and McCarthy et al. (2013) on associations of anthropometric/biomechanical measures and dance attractiveness, we speculate that physical strength is one of the features that characterize masculine male dance movements, and women may regard such dancers particularly attractive in a short-term mating context.

Acknowledgements: This project was funded by the German Science Foundation (DFG),

grant number FI 1450/4-1, awarded to B.F., and through the Institutional Strategy of the University of Göttingen. John T. Manning and Benedict C. Jones provided helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript.

Received 22 August 2013; Revision submitted 4 October 2013; Accepted 4 October 2013

References

Darwin, C. (1871). The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex. London: John Murray.

Feinberg, D. R., Jones, B. C., Law-Smith, M. J., Moore, F. R., DeBruine, L. M., Cornwell, R. E., . . . Perrett, D. I. (2006). Menstrual cycle, trait estrogen level, and masculinity preferences in the human voice. Hormones and Behavior, 49, 215-222.

Gangestad, S. W., Garver-Apgar, C. E., Simpson, J. A., and Cousins, A. J. (2007). Changes in women's mate preferences across the ovulatory cycle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92, 151-63.

Gangestad, S. W., Simpson, J. A., Cousins, A. J., Garver-Apgar, C. E., and Christensen, J. N. (2004). Women's preferences for male behavioral displays change across the menstrual cycle. Psychological Science, 15, 203-207.

Gangestad, S. W., Thornhill, R., and Garver, C. (2002). Changes in women's sexual interests and their partners' mate retention tactics across the menstrual cycle: Evidence for shifting conflicts of interest. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, 269, 975-982.

the Human Behavior and Evolution Society, Miami, FL.

Hanna, J. L. (2010). Dance and sexuality: many moves. Journal of Sex Research, 47, 212-241.

Harris, C. R. (2011). Menstrual cycle and facial preferences reconsidered. Sex Roles, 64, 669-681.

Havlicek, J., Roberts, S. C., and Flegr, J. (2005). Women's preference for dominant males’ odour: Effects of menstrual cycle and relationship status. Biology Letters, 1, 256-259.

Hugill, N., Fink, B., Neave, N., and Seydel, H. (2009). Men’s physical strength is associated with women’s perceptions of their dancing ability. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 527-530.

Jones, B. C., DeBruine, L. M., Perrett, D. I., Little, A. C., Feinberg, D. R., and Law Smith, M. J. (2008). Effects of menstrual cycle on face preferences. Archives of Sexual Behavior,37, 78-84.

Little, A. C., Jones, B. C., and Burriss, R. P. (2007). Preferences for masculinity in male bodies change across the menstrual cycle. Hormones and Behavior, 51, 633-639. McCarty, K., Hönekopp, J., Neave, N., Caplan, N., and Fink, B. (2013). Male body

movements as a possible cue to physical strength: A biomechanical analysis.

American Journal of Human Biology,25, 307-312.

Neave, N., McCarty, K., Freynik, J., Caplan, N., Hönekopp, J., and Fink, B. (2011). Male dance moves that catch a woman's eye. Biology Letters, 7, 221-224.

Penton-Voak, I. S., Perrett, D. I., Castles, D., Burt, M., Koyabashi, T., and Murray, L. K. (1999). Female preference for male faces changes cyclically. Nature, 399, 741-742. Peters, M., Simmons, L. W., and Rhodes, G. (2009). Preferences across the menstrual cycle

for masculinity and symmetry in photographs of male faces and bodies. PLOS ONE, 4, e4138.

Pound, N., Penton-Voak, I. S., and Surridge, A. K. (2009). Testosterone responses to competition in men are related to facial masculinity. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, 276, 153-159.

Provost, M., Troje, N., and Quinsey, V. (2008). Short-term mating strategies and attraction to masculinity in point-light walkers. Evolution and Human Behavior,29, 65-69. Puts, D. A. (2005). Mating context and menstrual phase affect women's preferences for

male voice pitch. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 388-397.

Puts, D. A. (2010). Beauty and the beast: Mechanisms of sexual selection in humans.

Evolution and Human Behavior,31, 157-175.

Rhodes, G. (2006). The evolutionary psychology of facial beauty. Annual Review of Psychology,57, 199-226.

Schwarz, S., and Hassebrauck, M. (2008). Self-perceived and observed variations in women's attractiveness throughout the menstrual cycle–A diary study. Evolution and Human Behavior,29, 282-288.

Thornhill, R., and Gangestad, S. W. (2006) Facial sexual dimorphism, developmental stability, and susceptibility to disease in men and women. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27, 131-144.

sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.