A SET OF 400 PICTURES STANDARDISED

FOR PORTUGUESE

Norms for name agreement , familiarit y

and visual complexit y for children and adult s

Sabine Pompéia

1, Mônica Carolina Miranda

1, Orlando Francisco Amodeo Bueno

2ABSTRACT - The present article provides normative measures for 400 pictured objects (Cycow icz et al., 1997) view ed by Port uguese speaking Brazilian Universit y st udent s and 5-7 year-old children. Nam e agreem ent , familiarity and visual complexity ratings w ere obtained. These variables have been show n to be important for t he select ion of adequat e st imuli for cognit ive st udies. Children’s name agreement w as low er t han t hat of adult s. The children also failed t o provide adequat e modal names for 103 concept s, rat ed draw ings as less familiar and less complex, and chose short er names for pict ures. The differences in rat ings bet w een adult s and children w ere higher than those observed in the literature employing smaller picture sets. The pattern of correlations among measures observed in the present study w as consistent w ith previous reports, supporting the usefulness of the 400 picture set as a tool for cognitive research in different cultures and ages.

KEY WORDS: picture, naming, familiarity, visual complexity, children, adults.

Conjunto de 400 figuras padronizadas para o português: normas de nomeação, familiaridade e complexidade visual para crianças e adultos

RESUM O - Est e art igo fornece dados normat ivos para o Brasil de um conjunt o de 400 figuras de objet os (Cycow icz et al., 1997) avaliados por estudantes universitários e crianças de 5–7 anos. Foram obtidos dados referent es à consist ência de nomeação, familiaridade com os objet os represent ados e complexidade visual dos desenhos. Existem evidências de que essas variáveis são importantes para a adequada seleção de estímulos para estudos cognitivos. A consistência de nomeação das crianças foi menor que a dos adultos. Em relação aos adult os, as crianças não conseguiram nom ear adequadam ent e 103 conceit os, avaliaram os desenhos como sendo menos familiares e menos complexos e escolheram nomes mais curtos para as figuras. As diferenças nas avaliações entre adultos e crianças foram mais altas que as observadas na literatura que envolveu conjuntos menores de desenhos. O padrão de correlações entre medidas observadas no presente trabalho são consistentes com relat os ant eriores, o que dá suport e à ut ilidade desse conjunt o de 400 figuras como ferrament a para pesquisas cognitivas em diferentes culturas e faixas etárias.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE: figura, nomeação, familiaridade, complexidade visual, crianças, adult os.

Department of Psychobiology, Universidade Federal de São Paulo (UNIFESP), São Paulo SP - Brazil. 1Graduate Student; 2Professor. Financial

Support : AFIP and FAPESP (grant no. 1998/15397-1).

Received 17 Oct ober 2000, received in final form 19 January 2001. Accept ed 26 January 2001.

Orlando F.A. Bueno - Departamento de Psicobiologia-UNIFESP - R. Botucatu 826, 1° andar - 04023-062 São Paulo SP - Brasil. FAX 55 11 5572 5092. E-mail: ofabueno@psicobio.epm.br

Naming object s is a fundament al abilit y t hat hu-mans use t o communicat e t hrough language. The apparent simplicit y of naming belies t he complexit y of its underlying cognitive processes1,2. Investigations

of t he underlying cognit ive processes involved in naming t herefore require t hat st udies be conduct ed under carefully cont rolled condit ions t hat have of-t en included of-t he use of picof-t ured objecof-t s as labora-t ory analogues of objeclabora-t labora-t hem selves. How ever, no normat ive dat a for such st imuli w as available unt il

t he end of t he 1970s, precluding adequat e compari-sons bet w een st udies t hat employed het erogeneous draw ings. A t urning point in t his line of st udy w as t he publicat ion of Snodgrass & Vanderw art ’s3 st

as size of draw ings (see 4), number of det ails and

orient at ion3.

Among t he most import ant aspect s of pict ure naming are name agreement , or t he rat e at w hich object s depict ed in t he draw ings are referred t o w it h t he same name, familiarit y w it h t he concept s and visual complexit y of t he draw ings. These measures are essent ially independent and may be assumed t o affect different st ages during pict ure processing5.

Name agreement is a robust predict or of naming difficult y and is import ant for st udies of naming la-tency, picture-name matching, recall, recognition and invest igat ions in w hich verbal coding is m anipula-t ed6. Familiarit y is an import ant predict or of pict ure

nam ing lat encies (t he m ore f am iliar t he concept s, t he short er t he naming t ime), w hile visual complex-it y affect s variables such as naming lat ency, t achis-t oscopic recogniachis-t ion achis-t hreshold and memorabiliachis-t y6.

Since t he pioneering paper of Snodgrass & Van-derw art3 in t he USA, sim ilar w ork has been

con-duct ed on t he 260 pict ure-set for Brit ish7, Spanish8,

Japanese9 and Icelandic populat ions. A prelim inary

adapt at ion int o Port uguese w as also accomplished w it h a smaller (150) set of pict ures11 . A larger set of

400 pictures has been studied more recently for both Nort h Am ericans5 and Frenchmen6. Normat ive dat a

for different languages show t hat despit e pict ures being judged t o be of similar familiarit y and visual complexit y, name agreement is specific t o t he par-ticular language investigated8. Hence, normative data

must be obt ained for every language under w hich research em ploying draw ings are conduct ed. In addit ion t o t he import ance of considering t he na-t ive na-t ongue of na-t he subjecna-t s used in sna-t udies of picna-t ure naming, t he age of part icipant s must also be t aken int o considerat ion. M ost of t he normat ive dat a cit ed above w as obt ained solely for universit y st udent s (> 18 years of age, hereaft er referred t o as adult s). Except ions are t he st udies by Berman et al.12 and

Cycow icz et al.5, w ho employed 7 t o 10, and 5 t o 7

year-olds, respect ively. Norms for t he younger chil-dren w ere found t o be different from t hose of bot h older children and adult s, suggest ing t hat t hey ex-hibit immat ure lexical and/or semant ic net w orks5.

Normat ive dat a in ot her languages must t herefore also include subject s of dif f erent ages in order t o assure that age-appropriate pictorial stimuli are avail-able. There is an obvious advant age at obt aining norm s f or sm all children because t he concept s t hat t hey can name correct ly are useful for all ot her ages and can be used in developm ent al st udies. Norm s f or young adult s are also essent ial in all languages because universit y st udent s const it ut e t he m ost

w idely used populat ion in st udies of cognit ive psy-chology.

The present st udy aimed at obt aining normat ive dat a on t he 400 pict ure-set proposed by Cycow icz et al.5 t o be used in Port uguese speaking

popula-t ions from Brazil. Subjecpopula-t s w ere middle-class univer-sit y st udent s and 5 t o 7 year-olds children. Name agreement , pict ure familiarit y, visual complexit y and lengt h of modal names w ere st udied, closely follow -ing Cycow icz et al.’s5 met hods.

METHOD

Subjects

All middle-class, nat ive Port uguese speakers w ho lived in t he cit y of São Paulo, Brazil. Their social-economic st a-t us w as dea-t ermined by a-t he ABIPEM E scale, developed by t he “ Brazilian Associat ion of t he Inst it ut e of M arket Re-search” .

a. Adult s: 150 universit y st udent s (24 m en), aged 23.6± 6.9 years (mean± SD).

b. Children: t hirt y-six children (18 boys), 5 t o 7 year-olds (83.9± 7.4 m ont hs; range 73-95 m ont hs), w ho had normal behaviour as assessed using t he CATRS-1013.

Stimuli

Four-hundred pict ures of common object s draw n in black over w hit e background5. These pict ure originat ed from different sources [pict ureset 1 cont aining 260 draw -ings3; pict ure-set 2 cont aining 61 draw ings12; pict ure-set 3 w it h 79 st ylist ically similar draw ings t o t he ones in t he first 2 set s but obt ained elsew here5]. The pict ures w ere randomly divided int o 5 list s of 80 pict ures. The order of present at ion of t hese list s w as balanced across subject s and sessions.

Procedure

Essent ially t he same as employed by Cycow icz et al.5, except t hat only naming, familiarit y and complexit y w ere det ermined. The et hics commit t ee approved t he prot o-col. Informed assent and consent forms w ere obt ained from t he adult part icipant s, t he children and t heir par-ent s.

con-sidered DKN (“ doesn’t know name” ) and familiarit y and complexit y rat ings w ere obt ained. If t he child failed t o answ er t he quest ions concerning t he nat ure of t he ob-ject , naming w as scored as DKO (“ doesn’t know obob-ject ” ) and t he next pict ure w as present ed. Pract ice pict ures w ere show n at t he beginning of each session. To illust rat e t he familiarit y rat ings, pict ures of an ice-cream (very familiar) and a light house (not at all familiar) w ere employed. For t he scores on complexit y, a t riangle (not complex) and a comput er (complex) w ere used as examples. In order t o reduce response bias, t he subject s w ere encouraged not t o rat e all pict ures using t he same point s in t he familiarit y and complexit y scale, but t o use t he w hole range of re-sponses possible. The children gave t heir rere-sponses aloud and t he experim ent er ent ered t he inf orm at ion int o re-sponse sheet s.

b. Adult s: subject s w ere run in groups (16 t o 45 indi-viduals) in 5 sessions separat ed by 5 minut e int ervals. The 400 pict ures w ere project ed sequent ially for 10 seconds each on a w hit e surface using a slide project or. Subject s w ere inst ruct ed t o use answ er sheet s t hat w ere given t hem t o ent er t he name of t he object s t hat w ere depict ed on t he slides. They w ere specifically t old not t o w orry about spelling. If t hey w ere unable t o name t he draw ing, t hey w ere inst ruct ed t o put dow n “ don’t know t he name“ (DKN) or “ don’t know t he object ” (DKO). Familiarit y w it h t he concept and visual complexit y of pict ures w ere also scored using 5 point scales (1 represent ed t he least familiar and complex) and subject s w ere inst ruct ed t o t ry t o use t he full range of scoring point s. Adult part icipant s received t he same inst ruct ions and pract ice pict ures as t he chil-dren. We chose t o inst ruct children and adult s t o use a different number of point s for t he rat ings of familiarit y and visual complexit y [children (1, 3 and 5) and adult s (1 t o 5)] because Cycow icz et al.5 cit e t hat a pilot st udy show ed t hat children do not assign rat ings across t he full range of numerical values used by adult s.

Measures

The follow ing measures w ere obt ained for each pic-t ure:

a. M odal nam e: t he nam e given by t he m ajorit y of subject s. Spelling m ist akes w ere correct ed. When t he children’s modal names w ere different from t hat of t he adult s’ t hey w ere classified by 2 judges int o one of 5 cat -egories: synonym (including local subst it ut es such as t he Sout h American feline “ onça” for leopard), superordinat es (such as bug for ant ), subordinat e (apple t ree for t ree), coordinat es (same cat egory, such as cockroach for beet le), com ponent (part of nam es, such as ball f or f oot ball), or failures (including definit ions of object s, such as “ t o make t hings” , and similar object s, such as clock for compass). Discrepancies bet w een judges w ere resolved by a t hird judge.

b . Nam e agreem ent : ref ers t o t he d egree t o w hich sub ject s agree on t he nam e of t he p ict ure. Tw o m ea-sures w ere used: t he percent age of subject s w ho used

t he m odal name and the H index, calculated in the follow -ing manner:

This index t akes int o account t he num ber of subject s t hat gives each one of t he different nam es used for t he same pict ure3,5. k refers t o t he number of different names given t o each pict ure, and t he Pi is t he proport ion of sub-ject s w ho gave each name. DKN and DKO do not ent er int o t he com put at ion of t his index. The great er t he nam -ing agreement bet w een subject s, t he closer t he H is t o 0. c. Familiarit y: refers t o t he familiarit y of t he concept depict ed. Scores ranged from 1 t o 5 (1= very unfamiliar, 2= unfamiliar, 3= medium, 4= familiar, 5= very familiar).

d. Visual complexit y: refers t o t he amount of lines and det ails in t he draw ing. Scores ranged from 1 t o 5 (1= least complex; 5= most complex).

e. Lengt h of modal name: number of let t ers in t he m odal nam e. In som e cases, m ore t han one m odal nam e w as available, so t he m ean lengt h w as calculat ed.

Word frequency is not available in Port uguese so it w as not included in t his st udy. Naming lat ency w as not assessed because adult subject s w ere not evaluat ed indi-vidually. We chose not t o assess image consist ency be-cause it w ould m ake rat ing sessions far t oo long for bot h children and adult s. Also, because age of acquisit ion w as not assessed in children, w e opt ed t o exclude t his mea-sure f rom t he evaluat ion of adult s.

Statistical analysis

Involved pict ures as unit s of m easure. The hypot hesis of normalit y and equalit y of variance of scores of adult and children on t he 7 measures invest igat ed (percent age of subject s w ho used t he m odal nam e, t he H st at ist ics, familiarit y, visual complexit y, w ord lengt h, DKN and DKO) f o r t h e w h o l e 4 0 0 p i ct u r e-set w er e t est ed u si n g Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Levene t est s, respect ively. M ost measures did not show normal dist ribut ion or homocedas-t icihomocedas-t y so non paramehomocedas-t ric homocedas-t eshomocedas-t s w ere employed. Spearman rho correlat ions bet w een t he seven measures w ere car-ried out for dat a of adult s and children separat ely. Spear-man r correlat ions of scores of each variable bet w een chil-dren and adult s w ere also obt ained. Scores of chilchil-dren and adult s w ere compared using M ann-Whit ney U t est . The level of significance used w as 0.01 because of t he large number of comparisons conduct ed. Paramet ric t est s (Pearson correlat ions and St udent t t est s) w ere also used in order t o enable comparisons w it h previous report s on t he pict ure-set s [Pearson correlat ions and t w o-t ailed St u-dent t t est s for indepenu-dent samples w ere also conduc-t ed conduc-t o analyse all resulconduc-t s obconduc-t ained here. The paconduc-t conduc-t ern of effect s w as unchanged (dat a not show n except for corre-lat ions bet w een dat a of adult s and children; see Table 4].

RESULTS

Table 1 cont ains t he f ollow ing indices f or t he w hole 400 pict ure-set for bot h age groups: H index

H=Σ Pi log (1/ )2 Pi

k

(nam e agreem ent ), percent age of subject s produc-ing t he modal name, familiarit y, visual complexit y, name lengt h, DKN and DKO.

Informat ion on each of t he 400 pict ures for bot h age groups [H index (name agreement ), percent age of subject s producing t he modal name, familiarit y, visual complexit y, name lengt h, DKN and DKO] and all alt ernat ive names given can be found at ht t p:// w w w .epm.br/psico/PSICO.HTM .

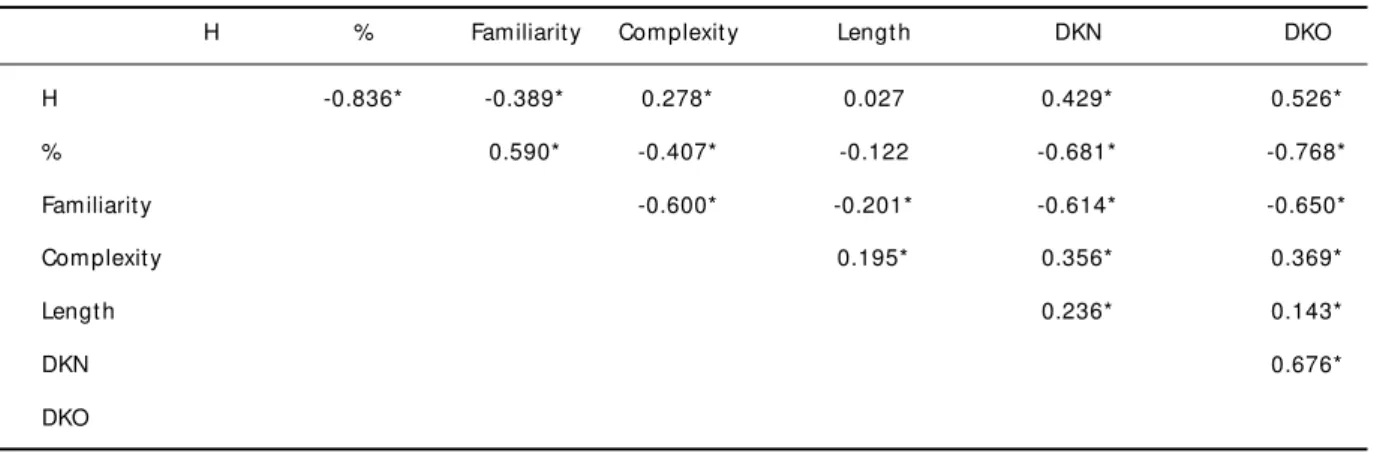

The correlat ion analysis conduct ed t o det ermine t he degree of relat ionship bet w een m easures f or adults and children can be found in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. Table 4 show s the correlations and com-parisons of t he 7 measures bet w een adult s and chil-dren.

The M ann-Whit ney U t est s bet w een measures f rom t he dif f erent age groups show ed t hat t he children’s percent age of name agreement w as low er t han adult s’, w hile t he H index and use of DKO (p< 0.001) and DKN (p< 0.01) w ere low er for adult s. The children also rat ed pict ures as less fam iliar and less complex (p< 0.001) and used short er names for pict ures (p< 0.01).

Tw o concept s had no modal name for t he adult s (t w o nam es w ere used for each concept w it h t he same frequency). The modal names given by t he adult s t o 24 of t he pict ures w ere not correct t rans-lat ions of t he int ended names in English (see ht t p://

w w w .epm.br/psico/PSICO.HTM ). These misnomers w ere separat ed int o 3 groups:

a. Ambiguous pict ures: 56 (chisel, misint erpret ed as a screw driver), 262 (basin, m isint erpret ed as a bat h), 298 (paddle, as a racket ), 299 (parachut e, as a balloon), 334 (callipers, considered t w eezers), and 340 (cymbals, a spool of t hread).

b. Int ended names in English t hat can be t rans-lat ed int o Port uguese but t hat w ere nevert heless named w it h common local subst it ut es: pict ures 136 (leopard), 159 (ost rich), 364 (lizard) and 394 (vul-ture) w ere misinterpreted as common animals of the Brazilian fauna (“ onça, ema, lagart ixa, urubu” , re-spect ively). Pict ure 261 (acorn) w as mist aken for a w alnut , pict ure 297 (net ) w as named w it h t he w ord “ rede” rat her t han “ puçá” (t he specific, albeit relat i-vely unknow n name for t his concept in Port uguese), draw ing 330 (blow fish) w as nam ed fish, and pic-t ure 386 (squash) w as mispic-t aken for a pic-t ypical Soupic-t h Am erican veget able (“ chuchu” ). Sim ilar nam es of clot hes w ere used for pict ures 125 (jacket ) and 224 (sw eat er). Pict ure 141 (lips) w as described as a mout h, w hile pict ure 149 (mouse) w as considered a rat . Also, pict ure 99 (French horn) w as mist aken for a t rombone and pict ure 243 (t rumpet ) for a cornet . Pict ure 283 (fishing reel) w as also considered a spool of t hread. Pict ure 345 (easel) w as mist aken for a blackboard. Finally, t he 2 pict ures t hat received no

Table 1. Summary statistics for adults and children for the 400 picture set.

Nam e Nam e Familiarit y Com plexit y DKN DKO Lengt h

agreement (H) agreement (%)

adult s children adult s children adult s children adult s children adult s children adult s children adult s children M ean 0.79 1.13 0.77 0.60 4.00 3.38 2.65 2.42 0.04 0.08 0.03 0.10 6.99 6.45 SD 0.73 0.79 0.25 0.30 0.65 0.77 0.76 0.50 0.09 0.11 0.08 0.15 3.15 2.81

N 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400 400

modal name could also be included in this category: picture 183 (racoon) w as named w ith the same fre-quency as a skunk and fox (“ gambá” and “ raposa” ) and picture 271 (closet) as “ closet” and “ armário” (cupboard).

c. Words t hat do not exist in Port uguese: pict ure 144 (mit t en, considered a glove), pict ure 373 (pret -zel, t hought of as a biscuit ).

Children provided 103 modal names that differed from those of adults and failed to determine a modal n am e f o r an ext r a 2 0 co n cep t s (see h t t p :// w w w .epm.br/psico/PSICO.HTM ). Synonyms, compo-nent s and superordinat e mist akes w ere observed 14 times each. Coordinate misnomers w ere the most fre-quent (28 concepts), w hile only one concepts w as clas-sif ied as a subordinat e. The judges disagreed only on 5 of t hese classif icat ions.

Table 2. Spearman’s rho correlations among the measures obtained from adults (see note of table 1; *p<0.01).

H % Familiarit y Com plexit y Lengt h DKN DKO

H -0.967* -0.474* 0.269* 0.160* 0.583* 0.513*

% 0.558* -0.312* -0.185* -0.656* -0.595*

Familiarit y -0.643* -0.123 -0.732* -0.565*

Com plexit y 0.159* 0.390* 0.242*

Lengt h 0.162* 0.113

DKN 0.684*

DKO

Table 3. Spearman’s rho correlations among the measures obtained from children (see note of table 1; *p<0.01).

H % Familiarit y Com plexit y Lengt h DKN DKO

H -0.836* -0.389* 0.278* 0.027 0.429* 0.526*

% 0.590* -0.407* -0.122 -0.681* -0.768*

Familiarit y -0.600* -0.201* -0.614* -0.650*

Com plexit y 0.195* 0.356* 0.369*

Lengt h 0.236* 0.143*

DKN 0.676*

DKO

Table 4. Comparison of scores of each measure between adults and children using parametric and non-parametric analysis (i.e. Pearson/ Spearman correlations and Student t tests/Mann-Whitney U test; *p<0.01; **p<0.001).

Pearson correlat ion Spearman rho correlat ion Student t Test M ann-Whit ney U t est

H 0.563* 0.627* -6.34* * -6.12* *

% 0.585* 0.670* 8.42* * -7.51* *

Familiarit y 0.835* 0.855* 48.17* * -11.250* *

Com plexit y 0.849* 0.852* 23.48* * -4.15* *

Lengt h 0.628* 0.628* 2.57* -2.68*

DKN 0.476* 0.685* -4.47* * -2.59*

DISCUSSION

The dist ribut ion of H values for t he adult s has a low mean and is posit ively skew ed, indicat ing t hat concept s have a high name agreement overall. The H of t he children w as larger, show ing t hat name agreement is not as high as adult s’. These result s are in accord w it h Cycow icz et al.’s5 dat a for Nort h

American speaking subject s of t he same age groups.

The fact t hat among t he 400 pict ures only 24 did not ref lect t he exact t ranslat ion of t he int ended names in English by adult s in t he present st udy indi-cates that the majority of the pictures from Cycow icz et al.5 represent concept s t hat are know n by

Brazil-ian universit y st udent s. Am ong t he dif f erences in nam ing, 16 ref lect ed use of com m on local subst i-t ui-t es, ali-t hough all bui-t 2 had H values higher i-t han the 75th percentile (Q3, see Table 1), suggesting that t hese concept s had lit t le naming consist ency. The except ions w ere pict ures 141 (lips) and 149 (mouse), w hich w ere consist ent ly nam ed as m out h (‘boca” ) and rat (“ rat o” ), respect ively. While mout h and lips are cert ainly adequat e descript ions of pict ure 141, t he w ord for mouse in Port uguese, “ camundongo” , possibly because it is so long, is of t en subst it ut ed for “ rat o” (rat ). Pict ures 144 (mit t en) and 373 (pret -zel) do not exist in Port uguese and should t herefore be avoided in st udies in t his language. Our dat a fur-t her suggesfur-t s fur-t hafur-t picfur-t ures 56 (chisel), 262 (basin), 298 (paddle), 299 (parachut e), 334 (callipers), and 340 (cym bals), should not be em ployed in any lan-guage as they proved ambiguous concepts and w ere named as different objects entirely. Alario & Ferrand6,

w ho conduct ed a st udy of t he 400 pict ures using French adult s, replaced 7 pict ures (no. 19, 95, 96, 283, 288, 327, 373) because t hey had been select ed in t he “ American context” . In the present study, only 2 of t hese pict ures (no. 96 and 327) had H scores below t he 75% percent ile, suggest ing t hat t hey might in fact be inadequat e for ot her cult ures.

Children named 103 concept s different ly from adult s and failed t o det ermine a modal name for 30 pict ures. Considering t he t ype of m isnom ers em -ployed by children w hen compared t o adult s, w e found t hat most w ere coordinat e mist akes, w hich appeared t w ice as oft en as synonyms, component s, and superordinat es, indicat ing t hat children t end t o error by confusing object in t he same semant ic cat -egory. Only 30 of the 103 differences in naming w ere failures, and in most cases t he names at t ribut ed t o the pictures resembled the object depicted (e.g. clock for compass). Overall, dat a on differences in nam-ing by adult s and children are in agreement w it h

resu lt s o b t ain ed f o r t h e sam e ag e g ro u p s b y Cycow icz et al.5, w ho found t hat Nort h American

children named 90 concept s different ly from adult s, t hat t hese differences w ere m ost coordinat e m is-t akes, and is-t hais-t naming failures did nois-t appear is-t o ref lect percept ual or f unct ional dif f erences am ong age groups, but rat her a lack of know ledge of part i-cular concept s by t he young children. For a more det ailed discussion on t he com parison of Brazilian and North American children see M iranda et al. (sub-mit t ed)14.

The correlat ion analysis conduct ed t o det ermine t he degree of relat ionship bet w een m easures f or adult s and children separat ely (Tables 2 and 3) sho-w ed t hat t he 2 measures of name agreement (H and %) w ere highly negat ively correlat ed alt hough cor-relations w ere much smaller w hen naming w as com-pared bet w een t he age groups. Naming has been show n not t o correlat e as highly as familiarit y and visual com plexit y8 w hen dat a obt ained in different

languages8 and ages12 are cont rast ed. This w as

con-firmed by our result s in t erms of t he comparison bet w een adult s and young children. The names at -t ribu-t ed -t o pic-t ures may also differ among subjec-t s w ho speak t he same nat ive language but w ho in-habit dist inct regions or count ries, are from differ-ent social and educat ional background, of differdiffer-ent ages, and possibly genders. Hence, pilot studies w ith t he specif ic populat ion t o be invest igat ed m ust al-w ays be conduct ed so as t o det ermine t he adequacy of t he norm s for each language.

The follow ing findings of correlat ions of relat ive m agnit ude suggest t hat concept s w hich w ere dif f i-cult t o name are lit t le know n by t he t w o age groups: t he percent age of name agreement and familiarit y w ere negat ively correlat ed w it h DKN and DKO, t he H index w as posit ively correlat ed t o DKN and DKO, and percent age of name agreement w as correlat ed posit ively w it h familiarit y. Familiarit y w as also nega-tively correlated w ith visual complexity for adults and children, suggest ing t hat subject s find less complex f igures m ore f am iliar as discussed by Snodgrass & Vanderw art3 and Berman et al.12. The reason for t his

effect is unknow n but it may be relat ed t o differ-ences in t he charact erist ics of t he draw ings, such as t he number of det ails used t o depict t he object s12.

in cognit ive st udies in w hich name agreement must be high, even if t heir H index seem s adequat e.

The remaining correlat ions w ere small (< 0.4) but w it h few except ions w ere highly significant . Word lengt h seems t o represent an independent at t ribut e of the pictures from the other measures investigated in t he present st udy because it correlat ed lit t le or not at all w it h t hem.

The correlat ions bet w een measures of adult s and children analysed separat ely w ere generally higher t han t hose obt ained from adult s of different coun-t ries using smaller secoun-t s3,5-8,12,, and also t han t hose

observed in st udies using all 400 pict ures3,6. The

rea-son for t his may be t hat w e combined rat ings on all 400 pict ures in t he sam e analysis [unlike Cycow icz et al.5, w ho divided t hem int o 3 set s] and used t he

same subject s t o rat e naming, familiarit y and visual complexit y [unlike Alario & Ferrand6], t hus low ering

variance w hich increases correlat ions. Nevert heless, t he consist ency in t he pat t ern of correlat ions among measures report ed for different cult ures and age groups is st ill m aint ained here, support ing t he use-fulness of t he 400 pict ure-set as a t ool for cognit ive research.

When dat a of Brazilian children w ere compared t o t hat of adult s, t he correlat ions w ere smaller t han t hose observed by Berman et al.12, w ho cont rast ed

rat ings of Nort h American 7 t o 10 year-olds and adult s for t he combined analysis of set s of 259 and 61 pict ures. This difference in effect s may be due t o 4 fact ors, independent ly or in combinat ion: a) older children may use rat ings t hat are more similar t o t hose of adult s t han 5 t o 7 year-olds’; b) Berman et al.12 seemed t o have used paramet ric analysis t hat

t end t o lead t o higher correlat ions bet w een mea-sures; c) t he t hird pict ure-set of 79 pict ures, added t o t he previous t w o set s t o make up t he 400 pic-t ures used here, include conceppic-t s pic-t hapic-t are less fa-m iliar t o young children, fa-m ore dif f icult t o ident if y and have low er frequency counts5, and therefore may

decrease t he int ercorrelat ion bet w een t he measures obt ained from young children and adult s for t he w hole 400 pict ure-set ; d) t he fact t hat t he Univer-sit y st udent s in t he present st udy consist ed basically of females. It is not possible t o det ermine in w hat w ay t he use of f ew m en could bias t he result s re-port ed here for lit t le is know n about gender differ-ences in naming, especially w hen speeded responses are not required. In fact , t he st udies on Snodgrass and Vanderw art ’s and Cycow icz’s pict ures did not

t ake gender int o account w hen analysing t he dat a (see 3,5-8) and Sanfeliu & Fernandez8 and Alario &

Ferrand6 even failed t o report t he sex of t heir

volun-t eers. Unforvolun-t unavolun-t ely volun-t he classes of Psychology svolun-t u-dent s t est ed (t he chosen course in t he ot her publi-cations of adult norms for the picture sets) had more female subjects. With the children, w ho w ere assessed individually, it w as possible t o select volunt eers so as t o include t he sam e num ber of boys and girls.

The comparison betw een age groups using M ann-Whit ney U t est s show ed differences among all mea-sures albeit t he signif icant correlat ions bet w een children’s and adult s’ dat a. Children’s name agree-ment w as low er and t he use of DKN and DKO w as higher t han t hat of adult s, show ing t hat children produced more alt ernat ive names and had more dif-f icult y nam ing concept s. In addit ion, t he children rat ed pict ures as less familiar and less complex t han adult s, possibly due t o t heir t endency t o show a smaller range and less variat ion in t heir rat ings5. The

children also chose short er nam es f or pict ures, re-flect ing t hat t he vocabulary of 5 t o 7 year-olds con-sist s of short er w ords, possibly because t hey are ac-quired earliest and are bet t er represent ed in t heir lexicon5. Taken together, these results are in line w ith

data presented by Cycow icz et al.5, although in many

cases t heir dat a show ed only a t rend of difference bet w een young children and adult s w hile ours reached highly significant effect s. This is not surpris-ing since w e used all 400 pict ures in t he same analy-sis w hile Cycow icz et al.5 divided t hem int o 3 set s,

w hich could have enhanced variances as discussed above. This illust rat es t he import ance of using larger amount s of pict ures w hen different populat ions are t o be compared.

We hope t hat t he normat ive dat a present ed here w ill be used as a guide f or t he select ion of pict orial st im uli t o be used in research in several f ields11.

In-vest igat ors w ho int end t o st udy semant ic memory using pict ured object s can f ind pict ures organised int o sem ant ic cat egories in Cycow icz et al.’s5 paper.

Those int erest ed in repet it ion prim ing should con-sult Snodgrass & Corw in15 for t he 150 pict ures t hat

present low t o moderat e complexit y and sufficient area to enable the creation of distinctly different frag-ment ed images.

REFERENCES

1. Johnson CJ, Clark JM, Paivio A. Cognitive components of picture nam-ing. Psychol Bull 1996;120:113-139.

2. Murtha S, Chertkow H, Beauregard M, Evens A. The neural substrate of picture naming. J Cogn Neurosci 1999;11:399-423.

3. Snodgrass JG, Vanderwart M. A standardised set of 260 pictures: norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, and visual com-plexity. J Exp Psychol Hum Learn Mem 1980;6:174-215.

4. Theios J, Amrhein PC. Theoretical analysis of the cognitive processing of lexical and pictorial stimuli: reading, naming, and visual and con-ceptual comparisons. Psychol Rev 1989;96:5-24.

5. Cycowicz, Y. M., Friedman, D., Rothstein, M., & Snodgrass, J.G. Pic-ture naming by young children: norms for name agreement, familiar-ity, and visual complexity. J Exp Child Psychol 1997;65:171-237. 6. Alario F-X, Ferrand L. A set of 400 pictures standardised for French:

norms for name agreement, image agreement, familiarity, visual com-plexity, image variability, and age of acquisition. Behav Res Method Instrum Comput 1999;31:351-552.

7. Barry C, Morrison CM, Ellis AW. Naming the Snodgrass and Vanderwart pictures: effects of age of acquisition, frequency, and name agreement. Quart J Exp Psychol 1997;50A:560-585.

8. Sanfeliu MC, Fernandez A. A set of 254 Snodgrass-Vanderwart pic-tures standardised for Spanish. Behav Res Method Instrum Comput 1996;28:537-555.

9. Matsukawa J. A study of characteristics of pictorial material. Memoirs of the faculty of Law and Literature: Shimane University. Shimane-ken, Japan, 1983.

10. Pind J, Jonsdottir H, Tryggvadottir HB, Jonsson F. Icelandic norms for the Snodgrass and Vanderwart (1980) pictures: name and image agreement, familiarity, and age of acquisition. Scand J Psychol 2000;41:41-48. 11. Pompéia S, Bueno OFA. Preliminary adaptation into Portuguese of a

standardised picture set for use in research and neuropsychological assessment. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 1998;56:366-374.

12. Berman S, Friedman D, Hamberger M, Snodgrass JG. Developmental picture norms: relationship between name agreement, familiarity, and visual complexity for child and adult ratings of two sets of line draw-ings. Behav Res Method Instrum Comput 1989;21:371-382.

13. Brito GNO. The Conner’s abbreviated teacher rating scale: develop-ment of norms in Brazil. J Abn Child Psychol 1987;15:511-518. 14. Miranda MC, Pompéia S, Bueno OFA. Norms for a 400 picture set in