FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS ESCOLA DE ECONOMIA DE SÃO PAULO

MARCELO GONÇALVES DA SILVA FONSECA

ESSAYS ON THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY: A CASE STUDY FOR BRAZIL

MARCELO GONÇALVES DA SILVA FONSECA

ESSAYS ON THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY: A CASE STUDY FOR BRAZIL

Tese apresentada à Escola de Economia de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Economia.

Campo de conhecimento: Teoria Econômica

Orientador: Pedro Luiz Valls Pereira

Fonseca, Marcelo Gonçalves da Silva.

Essays on the Credit Channel of Monetary Policy: a Case Study for

Brazil. / Marcelo Gonçalves da Silva Fonseca. - 2014.

108 f.

Orientador: Pedro Luiz Valls Pereira

Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Economia de São Paulo.

1. Macroeconomia. 2. Política monetária - Canal do crédito. 3.

Acelerador financeiro -. 4. FAVAR. -. 5. DSGE. -. 6. Econometria bayesiana.

I. Pereira, Pedro Luiz Valls. II. Tese (doutorado) - Escola de Economia de

São Paulo. III. Título.

MARCELO GONÇALVES DA SILVA FONSECA

ESSAYS ON THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY: A CASE STUDY FOR BRAZIL

Tese apresentada à Escola de Economia de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Doutor em Economia.

Campo de conhecimento: Teoria Econômica

Data de aprovação: 06/05/2014

Banca examinadora:

_____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Pedro Luiz Valls Pereira (Orientador) FGV-EESP

_____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Emerson Fernandes Marçal

FGV-EESP

_____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Eduardo Soares Gonçalves USP-FEA

_____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Marcelo Kfoury Muinhos

AGRADECIMENTOS

À minha família, em especial à minha amada companheira Fabiola, por todo apoio e incentivo na minha vida profissional e acadêmica. Agradeço às minhas queridas filhas Rafaela, Luiza e Giulia por terem suportado a inevitável perda de convivência em alguns momentos durante a jornada do doutorado.

Agradeço ao meu orientador Pedro Valls pelas contribuições fundamentais e grande dedicação à orientação dessa pesquisa.

Ao professor Emerson Marçal, pelos comentários valiosos em diversas etapas desse projeto.

Agradeço aos demais professores e membros do corpo diretivo por fazerem da Escola de Economia de São Paulo um motivo de inspiração e orgulhos para todos os alunos.

ABSTRACT

The onset of the financial crisis in 2008 and the European sovereign crisis in 2010 renewed the interest of macroeconomists on the role played by credit in business cycle fluctuations. The purpose of the present work is to present empirical evidence on the monetary policy transmission mechanism in Brazil with a special eye on the role played by the credit channel, using different econometric techniques. It is comprised by three articles.

The first one presents a review of the literature of financial frictions, with a focus on the overlaps between credit activity and the monetary policy. It highlights how the sharp disruptions in the financial markets spurred central banks in developed and emerging nations to deploy of a broad set of non conventional tools to overcome the damage on financial intermediation. A chapter is dedicated to the challenge face by the policymaking in emerging markets and Brazil in particular in the highly integrated global capital market.

This second article investigates the implications of the credit channel of the monetary policy transmission mechanism in the case of Brazil, using a structural FAVAR (SFAVAR) approach. The term “structural” comes from the estimation strategy, which generates factors that have a clear economic interpretation. The results show that unexpected shocks in the proxies for the external finance premium and the credit volume produce large and persistent fluctuations in inflation and economic activity – accounting for more than 30% of the error forecast variance of the latter in a three-year horizon. Counterfactual simulations demonstrate that the credit channel amplified the economic contraction in Brazil during the acute phase of the global financial crisis in the last quarter of 2008, thus gave an important impulse to the recovery period that followed.

In the third articles, I make use of Bayesian estimation of a classical neo-Keynesian DSGE model, incorporating the financial accelerator channel developed by Bernanke, Gertler and Gilchrist (1999). The results present evidences in line to those already seen in the previous article: disturbances on the external finance premium – represented here by credit spreads – trigger significant responses on the aggregate demand and inflation and monetary policy shocks are amplified by the financial accelerator mechanism.

RESUMO

O estouro da crise do subprime em 2008 nos EUA e da crise soberana europeia em 2010 renovou o interesse acadêmico no papel desempenhado pela atividade creditícia nos ciclos econômicos. O propósito desse trabalho é apresentar evidências empíricas acerca do canal do crédito da política monetária para o caso brasileiro, usando técnicas econométricas distintas. O trabalho é composto por três artigos. O primeiro apresenta uma revisão da literatura de fricções financeiras, com especial ênfase nas suas implicações sobre a condução da política monetária. Destaca-se o amplo conjunto de medidas não convencionais utilizadas pelos bancos centrais de países emergentes e desenvolvidos em resposta à interrupção da intermediação financeira. Um capítulo em particular é dedicado aos desafios enfrentados pelos bancos centrais emergentes para a condução da política monetária em um ambiente de mercado de capitais altamente integrados.

O segundo artigo apresenta uma investigação empírica acerca das implicações do canal do crédito sob a lente de um modelo FAVAR estrutural (SFAVAR). O termo estrutural decorre da estratégia de estimação adotada, a qual possibilita associar uma clara interpretação econômica aos fatores estimados. Os resultados mostram que choques nas proxies para o prêmio de financiamento externo e o volume de crédito produzem flutuações amplas e persistentes na inflação e atividade econômica, respondendo por mais de 30% da decomposição de variância desta no horizonte de três anos. Simulações contrafactuais demonstram que o canal do crédito amplificou a contração econômica no Brasil durante a fase aguda da crise financeira global no último trimestre de 2008, produzindo posteriormente um impulso relevante na recuperação que se seguiu.

O terceiro artigo apresenta estimação Bayesiana de um modelo DSGE novo-keynesiano que incorpora o mecanismo de acelerador financeiro desenvolvido por Bernanke, Gertler e Gilchrist (1999). Os resultados apresentam evidências em linha com aquelas obtidas no artigo anterior: inovações no prêmio de financiamento externo – representado pelos spreads de crédito – produzem efeitos relevantes sobre a dinâmica da demanda agregada e inflação. Adicionalmente, verifica-se que choques de política monetária são amplificados pelo acelerador financeiro.

CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 8

2 A SURVEY ON THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY ... 10

2.1 INTRODUCTION... 10

2.2 THE FINANCIAL ACCELERATOR AND THE BANK LENDING CHANNEL ... 10

2.3 THE CREDIT CHANNEL AND ECONOMIC CONTRACTION DURING THE GREAT FINANCIAL CRISIS ... 14

2.4 THE CREDIT CHANNEL AND THE INTERNATIONAL TRANSMISSION OF BUSINESS CYCLES ... 15

2.5 CREDIT CONSTRAINTS AND NON-CONVENTIONAL MONETARY POLICY: THE PRACTICE AND THE THEORETICAL EVALUATION ... 16

2.6 CHALLENGES FOR POLICYMAKING IN EMERGING MARKETS ... 19

2.7 THE CREDIT CHANNEL AND MONETARY POLICY IN BRAZIL ... 22

2.8 CONCLUSION ... 25

REFERENCES ... 26

3 CREDIT SHOCKS AND MONETARY POLICY IN BRAZIL: A STRUCTURAL FAVAR APPROACH ... 34

3.1 INTRODUCTION... 34

3.2 THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY ... 35

3.3 ECONOMETRIC STRATEGY ... 37

3.3.1 Credit channel in FAVAR models ... 39

3.3.2 Econometric model... 40

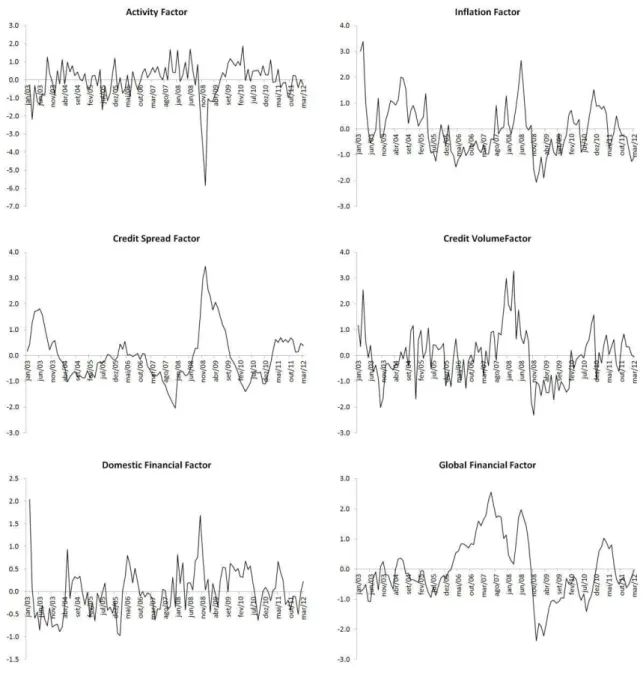

3.3.3 Identification of the structural factors ... 41

3.3.4 Estimation of the SFAVAR model ... 44

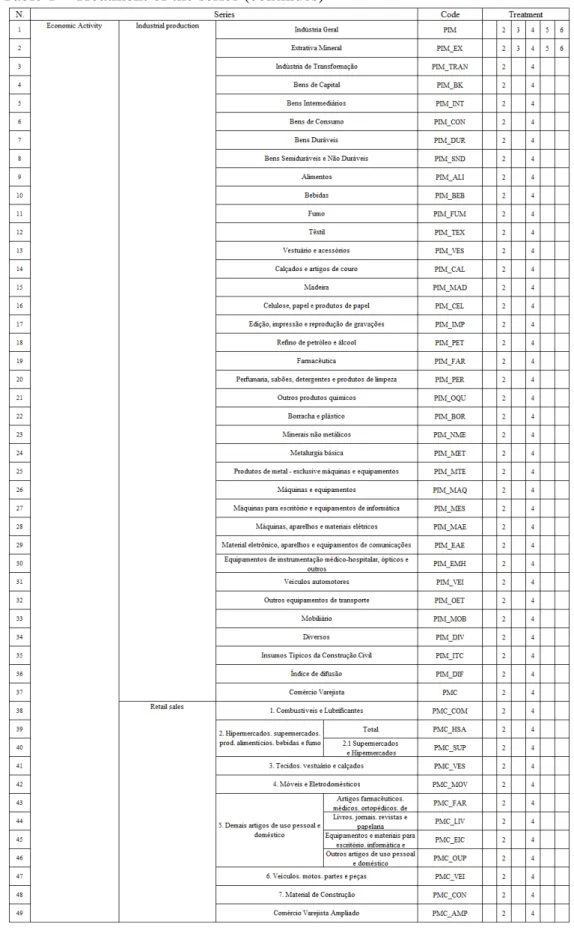

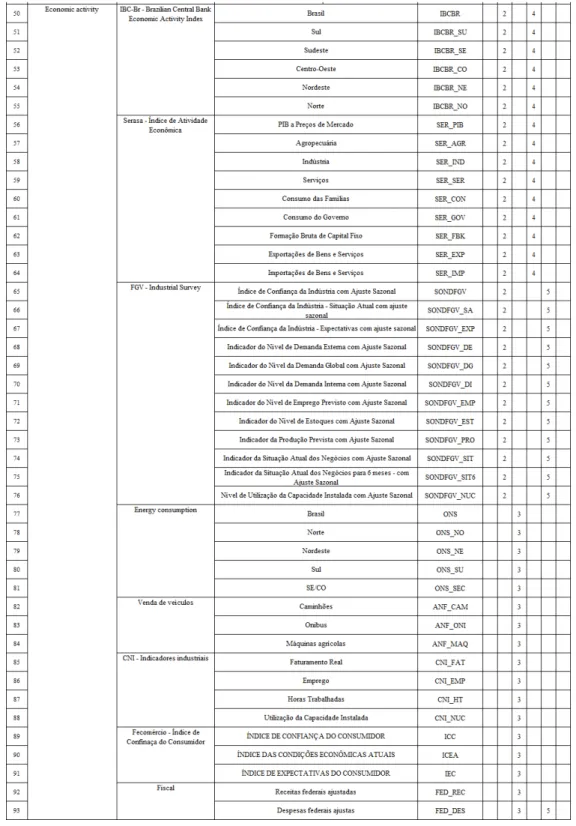

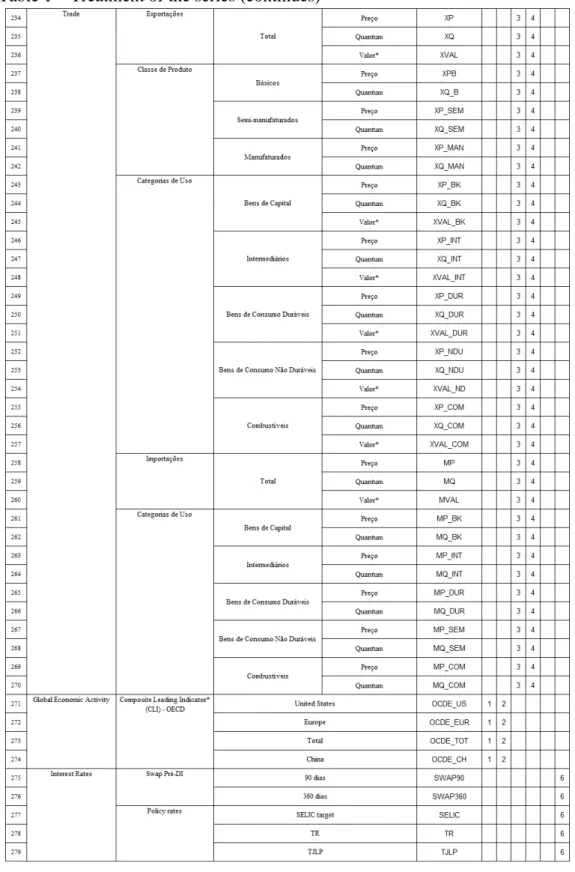

3.4 DATASET ... 45

3.5 RESULTS ... 47

3.5.1 Impulse response functions ... 48

3.5.2 Variance decomposition ... 50

3.5.3 Counterfactual Simulation ... 52

3.6 CONCLUSION ... 54

REFERENCES ... 56

APPENDIX ... 59

4 CREDIT SHOCKS AND MONETARY POLICY IN BRAZIL: EVIDENCES FROM A BAYESIAN DSGE MODEL WITH FINANCIAL ACCELERATOR CHANNEL ... 76

4.1 INTRODUCTION... 76

4.2 THE CREDIT CHANNEL IN A DSGE FRAMEWORK ... 76

4.3 THE MODEL ... 78

4.4 SHOCKS,DATA AND ESTIMATION ... 83

4.5.1 Parameters Estimates ... 87

4.5.2 Impulse response functions ... 87

4.5.3 Variance and shock decomposition analysis ... 88

4.5.4 Shock decomposition ... 90

4.6 AVARIANT SPECIFICATION... 90

4.6.1 Impulse response functions ... 92

4.6.2 Variance decomposition analysis ... 93

4.7 CONCLUSION ... 95

REFERENCES ... 96

APPENDIX ... 98

1 INTRODUCTION

Until recently, canonical macroeconomic models of business cycles used to treat the financial sector as a “veil”, in which the balance sheet composition of borrowers and lenders has no major effect on economic activity. However, the severe recession that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 renewed the interest of academic professionals and policymakers in properly understanding the linkages between the financial sector and the real economy. A number of recent analyses started to focus on the role played by financial intermediation as a channel to monetary policy. These studies find that disturbances originating in the credit sector played an important destabilizing role on the economic activity in the U.S. and other major nations during the great financial crisis.

Models that incorporate more a realistic description of the financial intermediation are important mainly for two reasons. First, it is widely known that financial variables have a predictive power to the business cycle. Second, a better understanding of the linkages between the financial and real sectors can give policymakers an edge in designing more efficient policy response strategies when faced to shocks, reducing the amplitude of the business fluctuation, lowering tax payer costs and therefore improving the welfare.

This work is an attempt to shed some light on the role played by credit sector in the business cycle in Brazil using two empirical strategies. The first methodology is a Structural Factor Augmented Vector Autorregressive model (SFAVAR). Over the past years, models based on factor analysis gained importance in empirical studies on monetary policy, as it allows the researcher to span large datasets and mitigates the problems related to the identification of shocks caused by the idiosyncratic element of individual series. The term structural comes from the estimation strategy, which generates principal components that have a clear economic interpretation. To assess the transmission of the credit shocks to the economy, I generate impulse response functions and carry out a variance decomposition analysis. In order to access the contribution of those shocks to the business cycle and the implicaitions to monetary policy in the period of study, I conducted counterfactual simulations.

spread is used as proxy for the external finance premium. Impulse response functions and variance decomposition confirm results seen in the SFAVAR analysis: monetary policy has long lasting effects and are amplified by the presence of credit frictions, while credit spreads shocks account for a large share of the economic activity fluctuation.

2 A SURVEY ON THE CREDIT CHANNEL OF MONETARY POLICY

2.1 Introduction

Until recently, canonical macroeconomic models of business cycles used to treat the financial sector as a “veil”, in which the balance sheet composition of borrowers and lenders has no major effect on economic activity. However, the sharp contraction in output that during the last global crisis gave rise to a large body of literature that departure from the highly stylized assumption of frictionless financial sector.

Models that incorporate more a realistic description of the financial intermediation are important mainly for two reasons. First, it is widely known that financial variables have a predictive power to the business cycle. Second, a better understanding of the linkages between the financial and real sectors can give policymakers an edge in designing more efficient policy response strategies when faced to shocks, reducing the amplitude of the business fluctuation, lowering tax payer costs and therefore improving the welfare.

In this work I conduct a review on the recent literature on the credit channel of monetary policy. The work is organized as follows. In the next section, I present the financial accelerator model and the bank lending channel, the main representations of the theoretical linkage between the financial sector and the business cycle. Section 2.3 presents some evidences that disruptions in financial intermediation magnified the economic contraction during the financial economic crisis of 2008 as well as the role played by the housing market. In section 2.4, I present some theoretical support for the global spillover of the financial crisis. Section 2.5 presents the policymakers’ response in mature economies and some works attempting to evaluate those actions in model simulations. Chapter 2.6 discusses the policymaking reaction in emerging markets, highlighting the arsenal of non conventional tools deployed. I dedicate Chapter 2.7 to the policy response and present some few works trying to assess the relevance of the credit channel in Brazil.

2.2 The financial accelerator and the Bank Lending Channel

complete markets and a frictionless financial sector, financial intermediaries act just like a “veil”, in the sense that they don’t play a particular role in business cycles. Consumers base their spending decisions entirely on their permanent wealth, so that movements in interest rates and asset prices are only relevant to the extent that they alter household’s financial wealth and the incentives to intertemporal consumption. At the same time, financial and credit market shocks can only influence business’s investment decisions by changing firms’ maturity risk-free cost of capital and, therefore, the market value of the capital stock relative to its replacement cost.

The theoretical link between credit and business cycles is provided by models that departure from the assumption of a frictionless financial sector and incorporate some imperfection, due to moral hazard and/or asymmetric information.

The first channel through which financial sector disturbances can have persistent effects is the bank lending channel or “narrow credit channel” (BERNANKE, 1983), which focus on the health of the financial intermediaries and the consequent impact over its ability to extend credit. A central function of banks is to screen and monitor borrowers, mitigating at least in part information and incentives problems. A monetary tightening or other shock that depletes banks reserves might force poorly capitalized banks to pull back their credit lines in order to restore their capital positions. As a result, banks are prevented from making use of their “information capital”, which will lead to bank-dependent firms and households that don’t have alternative sources of finance to contract spending, therefore deepening the real effects of the initial shock.

The other propagating mechanism of credit shocks exploited extensively in the literature is the “broad credit channel”, which operates through the creditworthiness of borrowers. Because creditors know that borrowers have the incentive to default when they have little equity attached to externally financed projects, they require that collaterals be attached in order to reduce the lender’s risk, and/or demand a higher premium to provide external funds. Thus, there is an “external finance premium” of externally raised funds in relation to the internal finance generated by cash flows owed to the incentive problem.

Bernanke and Gertler (1989), Kyotaki and Moore (1997), Bernanke, Gertler and Gilchrist (1999), Calrstrom and Fuerst (2001), Iacovello (2005) are among the main works exploiting the external finance premium channel.1

More recently, the broad credit channel has been formally modeled in a general equilibrium framework. In a seminal work, Gilchrist, Ortiz and Zakrajsek (2009) introduce Bernanke, Gertler and Gilchrist (1999) financial accelerator mechanism into the classical Smets and Wouters (2007) DSGE model to capture the linkages between the credit conditions and the real economy. They introduce two different sources of disturbance: a supply shock affecting the external finance premium, and a demand shock, affecting the balance sheet of the firm. Gertler and Kiyotaki (2010), Cúrdia and Woodford (2010) and Gertler and Karadi (2011) also succeeded in incorporating financial friction into classical New-Keynesian models.

Financial intermediation has changed profoundly over the past three decades as capital markets have become more deeply, liquid and accessible and non-depositary lenders. Therefore, banks do not rely exclusively on deposits as a source of funding. They can issue debt on the capital markets, or sell their portfolio of loans to broker dealers or originate-to-distribute businesses.

Nevertheless, the rise of non-bank lending doesn’t change the nature of the bank lending channel. In fact, non-deposit sources of capital are generally more expensive than deposits, reflecting the creditworthiness of the institution – a channel almost identical to the external finance premium discussed above, but instead of being related to the financial health of borrowers, it reflects the lender’s soundness. Therefore, this higher cost of banks’ funding will be passed through borrowers, and it will amplify monetary and real shocks. At the same time, nonbank lenders will also face an external finance premium, as they need to raise funds in the capital markets to finance their operations at a cost that will depend on their financial strength.

By focusing on the this link between banks’ financial condition and its cost of capital, the financial accelerator channel – through which the creditworthiness of the borrower can amplify and perpetuate monetary policy shocks – and the bank lending channel – the idea that banks have a special role in the transmission of monetary policy – “can be integrated into the same broad logical framework” (BERNANKE, 2007).

1 The information problem was behind Irving Fisher (1933) description of the debt-deflation characterization of

The flourishing theoretical literature gave rise to a vast amount of work aimed at finding empirical evidence and quantifying the relevance of credit channel. Kashyap and Stein (2000), Kishan and Opiela (2000) and Van den Heuvel (2002) corroborate empirically the validity of bank lending channel as they show that the lending activity of small banks is sensitive to their capital position. Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012) document that the “narrow credit channel” is also at work for large commercial banks operating in domestic markets.

Using an extensive dataset including more than 1,000 banks from the European Union and the US, Gambacorta and Marquez-Ibanez (2011) show that bank capital (especially core tier 1 ratio) influence loan supply shifts and that banks’ perceived risk is a very important determinant of loan supply. Still, they confirm that a long and persistent period of low rates can boost lending and induce to a more risk-taking behavior from financial institutions. Correa, Sapriza and Zlate (2012) present evidences that the large cuts in deposits issued by U.S. branches of European banks held by money market funds forced the parent banks to fund them, which exacerbated the slowdown in the economic activity during the recent European debt crisis. He and Krishnamurthy (2009) show that adverse macroeconomic conditions depresses banks’ capital base and reduces the risk appetite of the marginal investor, which increases the negative correlation between asset prices and risk-free interest rates.

Calomiris, Himmelberg and Wachtel (1995) and Gilchrist and Himmelberg (1999) present empirical evidence of the financial accelerator channel through the close relationship between cash flows and investment. Although some critics point that higher investments come together with larger cash flows because the latter provides a strong signal about future profitability, works that attempt to control for this misspecification problem still find that the cash flows are a relevant constrain for smaller firms, firms largely dependent on bank credit or with a poor financial health (GILCHRIST; HIMMELBERG, 1995).

Some works focusing on the external finance premium channel like Gertler and Lown (1999), King et al. (2007) and Gilchrist et al (2009), show that credit spreads are very good earlier indicators for recessions. Incorporating a methodology developed in Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2011) to construct a measure of financial distress from corporate sector bond prices in the secondary market, the authors simulate a DSGE model to show that widening credit spreads leads to a slowdown in economic activity, a decline in short-term interest rates and a long-lasting fall in inflation (GILCHRIST; ZAKRAJSEK, 2012).

Campello and Liu (2006) and Carroll, Otsuka and Slacalek (2011) show that the financial accelerator mechanism, through home equity withdraw, is an important driver of consumption decisions as they find a close relationship between house price changes and fluctuations in consumers spending.

Since the bank lending and the financial accelerator mechanisms can amplify the effects of shocks, they represent supplementary channels through which they monetary policy affects the economy. Changes in interest rates by the central bank affect the value of the borrowers’ assets and therefore the perception of their creditworthiness, leading to an increase in the external finance premium (the financial accelerator channel). At the same time, higher interest rates affect the supply and the cost offered by depositary institutions, as well as the external finance premium of non-depository lenders (the bank lending channel).

2.3 The credit channel and economic contraction during the great financial crisis

In light of the dramatic developments during the Great Financial Crisis, a number of empirical works focused on the contribution of the financial channels for the severity of the economic contraction. Under the DSGE model of Smets and Wouters (2007) extended to include financial frictions as in Bernanke, Gertler and Gilchrist (1999) show that the model successfully predicts a sharp contraction in economic activity along with a modest and more protracted decline in inflation, accurately describing the dynamics of the economy during the recent crisis and the subsequent recovery. Jermann and Quadrini (2012) estimates a DSGE model with nominal and financial frictions and show that under the assumption of constrains on firm’s ability to borrow, the model plays a good role explaining past business cycles, including the one during the Great Recession.

Until the burst of the great financial crisis, little or even none relevance was granted to housing market and its implications on the business cycle. However, given its prominent role assumed in the episode, a number of theoretical and empirical works has come to the fore, since it has been perceived that fluctuations on the housing market are not only a consequence of the macroeconomic adjustments but equally a prime source of business cycles2. Because housing transactions involve a large share of market debt, the models started to incorporate the role of financial intermediation in the housing cycle, especially after the

2008 crisis made it clear that housing prices movements can potentially affect the balance sheet of financial intermediaries. This is particularly true during crisis: if home prices fall below to the present value of their debts, borrowers can leave behind the collateral and walk away from their obligations, hurting the balance sheet position of financial intermediaries. Iacoviello (2014) finds that a negative shock to the balance sheet of financial intermediaries that leads borrowers – who use their home as collateral – to default on their loans forces poorly capitalized banks to deleverage, since the intrinsic nature of housing collateral prevents banks to reestablish their capital or liquidity position quickly. The deleveraging process then produces a credit crunch over credit dependent firms, propagating the shock to the rest of the economy. The author finds that this shock accounts for more than half of the decline in US output during the Great Recession. Ferrante (2012) adds the link between financial assets and home prices to the model of constrained banks of Gertler and Karadi (2011), and shows that a fall in the prices of dwellings is amplified by banks reducing their loans to the private sector, which generates co-movements in house prices, residential and business investments, and output.

2.4 The Credit channel and the international transmission of business cycles

Some papers such as Iacoviello and Minetti (2006) and Gilchrist, Hairault and Kempf (2002) adopt some form of constraint on agents’ ability to borrow abroad, which amplifies the international transmission of shocks. Assuming that investors holding domestic and foreign capital stock can only borrow from the domestic capital markets (due to limited credit enforceability), Dedola and Lombardo (2012) show under the model with financial frictions of Bernanke, Gertler and Gilchrist (1999) that a credit shock in one country contracts economic activity in the other.

Calibrating a DSGE model with two countries representing the European Periphery and the Core and a integrated banking sector, Guerrieri, Iacoviello and Minetti (2012) show that sovereign defaults in the Periphery lead to a very large output contraction in the core (as much as 50% of the GDP contraction in the Periphery). The reason is that banks in the Core carry domestic and foreign sovereign bonds, so the balance losses due to a default in the Periphery bonds forces banks to contract the volume of credit at home.

2.5 Credit constraints and non-conventional monetary policy: the practice and the theoretical evaluation

Over the recent years, this large body of theoretical and empirical research have fomented an intense debate on how and whether monetary policy should be adapted to cope with the implications of the so called “credit channel” to the monetary policy transmission mechanism. Taylor (2008), McCulley and Toloui (2008) and Meyer and Sack (2008) argue that a modification of the monetary policy rule to incorporate a response to changes in credit spreads can offset the real effects of financial distresses. However, this is still far to be a deep-rooted consensus in the theoretical research. Using a DSGE model with financial frictions, Cúrdia and Woodford (2010) find that there is not much welfare gain if the central bank deviates its policy reaction from the conventional inflation targeting rule, while De Fiore and Tristani (2009) show that an aggressive easing of policy is the optimal response to adverse financial market shocks.

of 2008 is a demonstration that the verdict is already adjourned from the perspective of the central banking practice.3

As the financial stresses roiled markets in 2007-2008, central banks in most advanced economies slashed policy rates close to or at the zero lower bound. In the US, the Federal Reserve reduced its target for the federal funds rate to the range of 0 to 25 basis points, which remains in place until today.

Notwithstanding this bold response, continued deterioration in credit markets urged monetary policy authorities to undertake a number of extraordinary measures to provide liquidity and mitigate the credit market strains. To overcome the surge in demand for reserve assets and the severe strains clogging the bank lending channel, the Fed engaged in currency swap agreements with other large central banks, created emergency lending facilities to bump liquidity directly to the system and forced the largest banks to raise capital buffers4. Similar responses were enacted by other major central banks.

Although those aggressive actions ultimately restored confidence in the financial system, the collateral damage of the financial disruptions to the economic activity was quite severe. With the unemployment rate looming large and the monetary policy conventional tool stuck at the zero lower bound, non-conventional measures were put in place to boost the economy.

One of those tools was the expansion of central bank’s balance sheets, dubbed interchangeably as “quantitative easing”, “credit easing” or “large scale asset purchases”. Throughout purchases mainly of government and government-like long-duration assets, policymakers sought to reduce the yields on those securities and other financial instruments in general5. Therefore, by easing broader financial conditions, economic activity could – at least in theory – be stimulated in a similar fashion as it would be the case throughout changes in the short-term interest rate – if they were otherwise possible. The balance sheet operations might also provide support to the economy through signaling and the confidence channels. Gertler and Karadi (2011) present a DSGE model with financial intermediaries that face endogenously determined balance sheet constraints and simulate a financial crisis to evaluate

3 See Bernanke (2012) for a good review on the main policy actions undertaken by the Federal Reserve. 4

Bernanke (2009) provides a comprehensive description of these measures.

the effects of central bank’s credit intermediation to offset a disruption of private intermediation. The authors show that although the monetary authority is less efficient than the private sector in allocating credit, it can elastically obtain funds by issuing riskless government debt, something that can have substantial welfare benefits during a crisis, especially when policy rates constrained at the zero lower bound.

Similarly, Gertler and Kiyotaki (2010) uses a canonical version of a DSGE model with financial frictions and a calibrated loss to the balance sheet of financial intermediators to evaluate the policy responses from the Fed and the US Treasury. The conclusion is that the credit easing policy works to dampen the output decline by mitigating the increase in spreads.

The recent sovereign debt crisis represented a breakthrough for monetary policymaking also for the European Central Bank (ECB), which remained restricted to providing short term liquidity to the region’s banking system during most of the time. However, as the vicious cycle between falling sovereign bond prices of peripheral countries and shrinking banks’ capital positions threatened a severe disruption in economic activity, the ECB put up in place a heavy arsenal, inaugurating a program to purchase peripheral sovereign bonds (Security Markets Purchase – SMP) and providing three-year loans to financial institutions at unlimited amounts (Long Term Repurchase Operations – LTRO) , with a very broad spectrum of assets eligible for collateral.

At the height of the crisis in September 2012, the ECB launched the Outright Monetary Transactions program (OMT) – a revamp of the former SMP attached with fiscal conditionalities and structural reforms to enhance competitiveness –“to be in the position to safeguard the monetary policy transmission mechanism…” as well as “to safeguard the monetary policy transmission mechanism in all countries of the euro area…” (DRAGHI, 2012).

The combined size of balance sheet of the four major central banks6 skyrocketed from US$ 4.5 trillion in January 2008 to US$ 9.4 trillion in December 2012. Some empirical studies suggest that this huge balance sheet expansion provided meaningful results. Estimates of Pandl (2012), Meyer and Bomfim (2012), Li and Wei (2012) of the combined effects of the two first rounds of Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAP) and the Maturity Extension Program point to a decline of the 10-year yields of the US Treasury bond in the range of 80 to 120 basis points. Also, Fuster and Willen (2010) and Wright (2012) report significant declines in the external finance premium of corporate bonds and mortgage backed securities in US. Using

Federal Reserve Bank models, Chung et al (2012) estimate the first two LSAP provided a 3% boost to GDP and increased employment by 2 million jobs7.

Joyce, Tong and Woods (2011) compilation of estimates on the effects of the Bank of England’s quantitative easing program point to the range from 1.5-2% for real GDP and up to 1.5% for inflation in UK. Although the OMT has so far not been activated, its simple announcement has sent markets the message that the ECB would be in fact acting as a lender of last resort to Eurozone members states, pushing sovereign bond yields of Spain and Italy – the two major countries in the heart of the crisis – close to their lower levels since the burst of the Eurozone crisis in 2010. Since then, banks’ stock prices in the region rallied, the ECB’s surveys point to a halt in credit contraction, deposits outflows from banks in the periphery have stabilized and money market rates came down to normal levels. Though still a modest improvement, business confidence surveys in the region have started to rebound, signaling a positive feedback loop from stabilizing financial and credit markets to the economic activity.

Central banks have been also making use of communication tools to boost the amount of support to the economic recovery. Since 2009 the Federal Reserve has been making explicit guidance about the future course of the federal funds rate. The idea is that “forward guidance” about future actions can provide easier financial conditions through lower long term interest rates. In the end of last year, the FOMC moved even further with the forward guidance strategy, announcing explicit thresholds for future policy firming – an inflation rate higher than 2.5% and unemployment rate below 6.5%. Results of the communication tool are very tricky to quantify, but asset prices response to shifts in the Fed’ forward guidance is a point in favor to its effectiveness in shaping agents’ expectations about future policy action.

2.6 Challenges for policymaking in emerging markets

Although emerging countries were not at the epicenter of the crisis, the panic following the debacle of systemically important institutions in the U.S. in September 2008, cross-border shocks rapidly spread to their financial sectors, with severe consequences for the economic activity. Tanks to very sound macro and financial fundamentals conquered through

decades-long adjustment efforts, for the first time emerging nations were able to respond with counter-cyclical policies. It didn’t take long for most of those countries to rebound.

After a short lived bounce, structural issues related to debt overload, banking sector deleveraging and little room for maneuver from conventional policy stimulus weighted on advanced economies recovery. Providing high amounts of liquidity was therefore the major central banks’ policy tool of last resort, which affected international financial markets and resulted in spillover effects over emerging markets. Interest rate, risk and growth differential produced a strong demand for emerging market assets and aggressive capital inflows into those countries.

This environment posed a challenge to emerging markets’ policymakers, as the strong capital inflows added to inflationary pressures that were already creeping up due to the fast cyclical recovery. In particular, those flows exacerbated the pro-cyclicality of the financial sector operating through the bank landing channel: as they reduced the cost of funding, financial institutions relaxed credit standards and expanded lending operations, adding more stimulus to an already booming aggregate demand. This mechanism weakened the effects of the monetary tightening in place in many emerging markets, as the cost of funding is a major transmission channel through which monetary policy operates. More worrisome, it enhanced the vulnerability of the financial system to “sudden stops”, since a large part of this excessive lending was directed to riskier segments of the market at a time when they increased foreign currency mismatches. Credit linkages therefore moved to the core of conventional monetary policy, and proposals to a compressive framework contemplating both price and financial stability emerged.

Actually, the debate on how the central bank should react to asset price bubbles is not new. Motivated by the Japan’s property market burst in the 80’s, the U.S. stock market collapse in the 90’s and the many emerging markets crises over the past decades, some argued8 that central banks should react preemptively to wealth effects produced by lower external premium and the bank lending channels, as those effects would ultimately be transmitted to excessive consumption and higher inflation. Moreover, they reminded that even in an environment of price stability, excessively pro-risk behavior in the financial sector could foster asset bubbles.

However, the dominant view was that a clear separation principle should hold: use of the micro-prudential tools to promote financial stability and conventional instruments to

achieve price stability. At the same time, the consensus among policymakers and within the academic community was that identifying asset bubbles posed a big practical challenge, so that monetary policy should not target them9.

The last global financial crisis posed the playfield not only for central banks to incorporate the credit channel into their reaction functions, but also to consider explicitly the interactions between monetary policy and prudential regulation10. Therefore, a number of emerging markets central banks started to implement traditional prudential and regulatory guidelines into a macroeconomic context, with an eye on the rising systemic risk. This approach, named at “macroprudential” regulation, aimed at strengthening the financial system and avoiding potential excessive lending behavior on the upturn of the business cycle11.

The main macroprudential instruments deployed by the monetary and the regulation authorities to “lean against the wind of the financial cycle” were: higher capital and liquidity requirements during the expansion to guarantee buffers that could be used in downturns; more stringent and forward-looking provisioning rules; limits to concentration, loan size, debt-to-income levels, and currency mismatch; systemic capital surcharges12.

A number of studies attest that the macroprudential instruments were quite effective in terms of reducing the pro-cyclicality of financial systems and minimizing the systemic risks13.

Recently, a literature has emerged exploring analytically the inflationary and destabilizing effects of surges in capital inflow, as well as mutual interactions between macroprudential and conventional instruments in a standard DSGE model with a credit block and counter-cyclical rules14. Agénor, Alper and Silva (2012) show that sudden capital inflows generate an expansion in credit, activity, inflation and asset prices pressures. Besides, countercyclical regulation in the form of Basel III-type rules, based on real credit gaps (understood as the gap between the actual stock of credit and its long term trend) is effective

9 Bean (2003), Bernanke and Gertler (2001), Greenspan (2002), Mishkin (2008).

10See the report “Rethinking Central Banking” written by the Committee on International Economic Policy

Reform.

11 Agénor and Silva (2012a) provide a good review of the literature.

12 See the 2010 report of the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS) of the BIS for a compilation of the available macroprudential instruments and framework, as well as the experiences using them.

13

in promoting macroeconomic stability (lower volatility in output gap and inflation) and financial stability (lower volatility in FX rates and house prices).

2.7 The credit channel and monetary policy in Brazil

Bearing the sound macroeconomic pillars, Brazilian economy posted a very robust growth in the years preceding the great financial crisis, breaking with the two-decade long stagflation. The aggressive disinflation strategy put in place right after Brazilian electoral crisis of 2002, the pursue of high primary fiscal surpluses, and the adoption of a flexible exchange rate regime contributed to curb fears regarding debt sustainability, helped to enlarge businesses’ planning horizons and fostered the return of foreign capitals.

This environment of much reduced macroeconomic risk set the stage for a rapid expansion of the credit activity, which struggled during the periods of heightened uncertainty and lagged behind the level of penetration observed in most of other emerging market nations. From December, 2003 to September, 2008, Brazil witnessed a credit expansion from 24.6% of GDP to 40% of GDP.

As it was the case with most of emerging markets, Brazilian solid fundamentals didn’t prevent the country to be severely hit by the panic following Lehman Brothers’ collapse. In the last quarter of 2008, industrial production collapsed -60% ar, and loans (inflation-adjusted) fell 1.7% ar, and the exchange rate depreciated 18% .

Brazilian authorities took aggressive actions to offset the liquidity and credit crunch, the sharp capitals outflows and the large contraction in the economic activity. The Brazilian Central Bank lowered banks’ reserve requirements, provided foreign exchange lines of credit to the private sector, offered almost USD15 billion in spot market and exchange swap contracts totaling USD33 billion. Deposit guarantee schemes were introduced. Conventional counter-cyclical policies were also deployed. The Central Bank slashed the Selic rate by 500bp to 8.75%15. On the fiscal front, tax cut were put in place and the primary surplus lowered from 3.8% of GDP in 2008 to 2.5% of GDP in 2009. On the quasi-fiscal side, public sector’ banks expanded loan to the private sector by more than 3% of GDP.

The Brazilian economy responded quickly to that large amount of stimulus, and in the third quarter of 2009 the GDP resumed its upward trend. In 2010, signs of overheating were clear (GDP growth would reach 7.5% in that year), with inflationary pressures resulting

from supply and demand imbalances together with shocks from global commodity prices. As a result, the Brazilian Central Banks inaugurated another round of monetary policy tightening. As in many other emerging nations, Brazilian policymakers were facing the same challenging environment resulting from the combination of international “pull factors” (growth stagnant, low returns, private and public sector deleveraging and abundant liquidity in the advanced economies) and domestic “push factor” (fast growth, large interest rates, good fundamentals and high return for capital) which engendered massive capital inflows, part of which directed to the credit market.

In fact, credit operations in Brazil were again growing briskly. In the period between January, 2009 and December, 2010, credit-to-GDP ratio increased 3p.p. to 40.5%. The BCB was particularly concerned16 to specific sources of risk for financial stability, such as currency mismatch in banks’ balance sheets, the fast increase in households’ debt burden, the rise of riskier modalities (such as revolving credit lines and credit card loans), maturity expansion beyond prudent levels (especially in car loans, which passed 60 months in some cases) and deteriorating quality of collaterals. Those were particularly true for small and medium size-banks, as they could not rely on a significant deposit base. Moreover, as Sales and Barroso (2012) argument, the excessive credit growth weakened the transmission of the monetary policy tightening.

In December 2010, the Central Bank of Brazil inaugurated a round of macroprudential measures in order to anticipate potential sources of financial instability: increased bank reserve requirements to curb the transmission of global liquidity into the domestic credit market; higher capital requirements for some modalities in order to correct for deteriorating credit quality; new reserve requirements on banks’ short positions in the foreign exchange market and taxation in external credit inflows to reduce balance sheet foreign currency mismatches and avoid excessive FX volatility.

As Harris and Silva (2012) document, the increase reserve and capital requirements together with the Selic rate hikes were successful in reducing credit growth, affecting not only the volume of new loans, but also de interest rates and maturity. The reserve requirement on short foreign currency positions and the taxation were effective in taming capital inflows in derivative and spot markets, reducing vulnerabilities in the banking sector coming from balance sheets’ currency mismatches.

At the second half of 2011, Brazilian economy was already slowing down as a result of the policy tightening. That trend would be intensified in the following quarters by the renewed deterioration in the international scenario, resulting from a combination of very stressful events – the debt ceiling debate in the U.S. (which ultimately resulted in the cut of the country’s triple-A rating by Moody’s) and the escalation of the European sovereign debt crisis as it hit systemic countries (Spain and Italy), which brought the global financial systemic once again close to a halt.

Faced with such environment, the BCB reversed course in the monetary policy front in August, an initiated a series of cut that would ultimately bring the Selic rate 525bp down to 7.25%. With credit expanding at a more sustainable rate, the authorities also implemented a fine tuning on the macroprudential front, partially relaxing capital requirements for some credit modalities and exempting from taxation the foreign debt operations with maturity higher than two years.

Few works have dedicated attention to the credit channel of monetary policy in Brazil, the main reason being the fact that credit activity had only a small penetration in the economy until the second half of last decade. Therefore, it was relegated to the back seat in terms of its importance for the empirical understanding of how monetary policy operates.

In Nakane and Takeda (2002), the impulse response function from Vector Autorregressive Model (VAR) show that innovations in the policy rate after the supply of non-earmarket credit after four months.

Carneiro, Salles and Wu (2003) estimate the demand of firms for credit, treating the endogeneity problem between the volume of credit and interest rates. The results show that a contracionist monetary policy shock affects negatively the demand for credit.

2.8 Conclusion

The great financial crisis renewed academic and policymakers interest to better understand the linkages between developments in the financial sector and the real side of the economy. In this work, I presented a review of the literate on the subject, paying an especial attention to the close ties between the practice and theory of monetary policy.

The main conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- There has been a significant profusion of literature incorporating more realistic descriptions of financial frictions in general equilibrium models, relying in some form of external finance premium, either of borrowers or lenders.

- Different empirical techniques – either through calibrated/simulated DSGE models or reduced form models – revel that disruptions in financial intermediation were in the core of the unprecedented output contraction during the great financial crisis.

- Some models allow identifying fluctuations in the housing sector as a source of volatility in the balance sheet of banks and, therefore, can have relevant spillover effects to the rest of the economy by affecting banks’ capacity to lend.

- Limits to leverage, integrated sovereign bond markets and constrains to borrow abroad are channels thorough which shocks are transmitted internationally.

- It is general consensus that the extraordinary policy action during the height of the crisis contributed to limit economic downturn caused by disruptions in financial intermediation.

- Although theory is still lagging behind the practice in terms of non conventional monetary policy, some works have successfully incorporated the type of tools deployed during the global crisis in formal general equilibrium models.

REFERENCES

AGÉNOR, P. R.; SILVA, L. P. Macroeconomic stability, financial stability, and monetary policy rules. Journal of International Finance an Economic and Economic, Turlock, v. 15, n.2, p. 205-224, 2012.

AGÉNOR, P. R.; ALPER, K.; SILVA, L. P. Capital requirements and business cycles with credit market imperfections. Turkey: The World Bank, 2009. (Policy Research Working Paper, n. 5151)

AHMADI, P. Creidt shocks, monetary policy and business cycles: evidences from a structural time varying bayesian FAVAR. Frankfurt: Goethe University, 2009. Mimeo.

ALMEIDA, H.; CAMPELLO, M.; LIU, C. The financial accelerator: evidence from

international housing markets. Review of Finance, Philadelphia, v. 10, n. 3, p. 321-352, 2006. ANDRÉS, J.; LÓPEZ-SALIDO, J.; NELSON, E. Tobin's imperfect asset substitution in optimizing general equilibrium. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Columbus, v. 36, n. 4, p. 665-690, 2004.

AOKI, K.; PROUDMAN, J.; VLIEGHE, G. houses as collateral: has the link between house prices and consumption in the uk changed? Economic Policy Review, New York, v. 8 n. 1, p. 163-177, May, 2002.

BAI, J.; NG, S. Confidence intervals for diffusion index forecasts and inference for factor-augmented regressors. Econometrica, Chicago, v. 74, n. 4, p. 1133-1150, jul. 2006: BARROSO, J. B. R. B.; SALES, A. S. S. Coping with a complex global environment: a Brazilian perspective on emerging market issues. Brasília, 2012. (Working Paper Series, n. 292).

BAUMEISTER, C.; BENATI, L. Unconventional monetary policy and the great recession: estimating the impact of a compression in the yield spread at the zero lower bound. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 2010. (Working Paper Series, n. 1258)

BEAN, C. Asset prices, financial imbalances and monetary policy: are inflation targets

enough? Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements, 2003. (BIS Working Paper, n. 140). BELVISO, F.; MILANI, F. Structural factor-augmented VARs (SFAVARs) and the effects of monetary policy. The B.E. Journal of Macroeconomics, v. 6, n. 3, p. 1-46, 2006.

BERNANKE, C. B. S. Monetary policy since the onset of the crisis. In: ECONOMIC SYMPOSIUM, Kansas City. 31 Aug. 2012. Disponível em:

<http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20120831a.htm>.Acesso em: 25 fev. 2014.

______. The crisis and the policy response. London: London School of Economics, 13 Jan. 2009. Disponível em: <http://www.federalreserve.

gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20090113a.htm>. Acesso em: 25 fev. 2014. ______. The financial accelerator and the credit channel. In: CONFERENCE THE

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF ATLANTA , 21., Atlanta, 15 Jun. 2007. Disponível em: <http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/ speech/bernanke20070615a.htm>. Acesso em: 25 fev. 2014.

BERNANKE, B.; GERTLER, M. Should central banks respond to movements in asset prices? The American Economic Review, Nashville, v. 91, n. 2, p. 253-257, 2001.

BERNANKE, B.; GERTLER, M. Agency costs, net worth, and business fluctuations. The American Economic Review, Nashville, v. 79, n. 1, p. 14-31, 1989.

BERNANKE, B.; BOIVIN, J.; Eliasz, P. Measuring the Effects of Monetary Policy: A Factor-augmented Vector Autoregressive (FAVAR) Approach. The Quarterly Journal of Economics (MIT Press), v. 120, n. 1, p. 387-422, 2005.

BERNANKE, B.; GERTLER, M.; GILCHRIST, S. The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In: ______. The Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1. New York: Princeton University, 1999. Chap. 21, p. 1341-1393.

BEVILAQUA, A.; MESQUITA, M.; MINELLA, A. Brazil: taming inflation expectations. Brasília, jan. 2007. (Working Paper Series, n. 129).

BLANCHARD, O. What do we know about macroeconomics that fisher and wicksell did not? February 2000. (Working Paper Series, n. 7550).

BOIVIN, J.; GIANNONI, M.; STEVANOVIC, D. Dynamic effects of credit shocks in a data-rich environment. Social Science Research Network, New York, 2012. (FRB of New York Staff Report, n. 615).

BORIO, C.; LOWE, P. Asset prices, financial and monetary stability: exploring the nexus. Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements, 2002. (BisWorking Paper, n. 114). Disponível em: <http://www.bis.org/publ/work114.htm>. Acesso em: 21 fev. 2014.

CAMPBELL, J.; COCCO, J. How do house prices affecct consumption? Evidence from micro data.” Journal of Monetary Economics, Amsterdan, v. 54, n. 3, p. 591-621, Apr. 2008.

CARLSTROM, T.; FUERST, T. Monetary policy in a world without perfect capital markets. Cleveland: Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, 2001. (Working Paper, n. 0115,).

CARROLL, C.; OTSUKA, M.; SLACALEK, J. How large are housing and financial wealth effects? A new approach. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Columbus, Ohio, v. 43, n. 1, p. 55-79, Feb. 2011.

CARTER, C.; KOHN, P. On gibbs sampling for state space models. Biometrika, London, v. 81, n. 3, p. 541-553, 1994.

CECCHETTI, S.; GENBERG, H.; LIPSKY, J.; WADHWANI, S. Asset prices and central bank policy. Geneva: International Centre for Monetary and Banking Studies and Centre for Economic Policy Research, 2000. (The Geneva Reports on the World Economy 2).

CETORELLI, N.; GOLDBERG, L. Banking globalization and monetary transmission. Journal of Finance, New York, v. 67, n. 5, p. 1811-1843, Oct. 2012.

CHUNG, H.; LAFORTE, J. P.; REIFSCHNEIDER, D.; WILLIAMS, J. Have we

underestimated the likelihood and severity of zero lower bound events? Jan. 2011. p. 47-82. (Working paper, n.11-01).

CLAESSENS, S.; GHOSH, S. Macro-Prudential Policies: Lessons for and from Emerging Markets. In: EWC–KDI CONFERENCE FINANCIAL REGULATIONS ON

INTERNATIONAL CAPITAL FLOWS AND EXCHANGE RATES, 2., Hawai, 19–20 Jul. 2012. Disponível em: < http://www.g24.org/TGM/Macro-Prudential%20Policies.pdf >. Acesso em 22 fev. 2014.

CORREA, R.; SAPRIZA, H.; ZLATE, A. Liquidity shocks, dollar funding costs, and the bank lending channel during the european sovereign crisis. Nov. 2012. (International Finance Discussion Paper, n.1059).

CÚRDIA, V.; WOODFORD, M. Credit spreads and monetary policy. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2009. (Working Papers, n. 15289).

DEDOLA, L.; LOMBARDO, G. Financial frictions, financial integration and the international propagation of shocks. Economic Policy, Cambridge, v. 27, n. 70, p. 319-59, Abr. 2012. DEL NEGRO, M.; GIANNONI, M.; SCHORFHEIDE, F. Inflation in the great recession and new keynesian models. Staff Reports, New York, n. 618, May 2013.

EICKMEIER, S.; LEMKE, W.; MARCELLINO, M. The changing international transmission of financial shocks: evidence for a classical time-varying FAVAR. Frankfurt: Deutsche Bundesbank, 2011. (Discussion Paper Series 1: Economic Studies n. 05/2011).

FAVARA, G.; DE NICOLÒ, G.; RATNOVSKI, L. Externalities and macroprudential policy. Washington: International Monetary Fund, 2012. (Staff Discussion Note SDN/12/05).

FERRANTE, F. A model of housing and financial intermediation. New York, Sep. 2012. Disponível em: <https://files.nyu.edu/ff481/public/Ferrante_ Housing.pdf >. Acesso em 15 fev. 2014.

FIORE, F.; TRISTANI, O. Optimal monetary policy in a model of the credit channel. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 2009. (Working Paper Series, 1043)

FISHER, I. The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions. Econometrica, Chicago, v. 1, n. 4, p. 337-57, 1933.

FRIEDMAN, M.; SCHWARTZ, J. Monetary trends in the united states and the united kingdom: their relation to income, prices, and interest rates. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1982.

FUHRER, J.; OLIVEI, G. The estimated macroeconomic effects of the federal reserve's large-scale treasury purchase program. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2011. (Public Policy Briefs, n. 11-2).

FUSTER, A.; WILLEN, P. $1.25 trillion is still real money: some facts about the effects of the federal reserve's mortgage market investments. Boston: Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2010. (Public Policy Discussion Papers, n. 10-4).

GAMBACORTA, L.; MARQUEZ-IBANEZ, D. The bank lending channel: from the crisis. London: European Central Bank, 2011. (Working Paper Series, n. 1335).

GELMAN, A.; RUBIN, D. A single sequence from the gibbs sampler gives a false sense of security. In: BERNARDO, J. M.; BERGER, J. O.; DAWID, A. P.; SMITH, A. F. M. Bayesian statistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

GEMAN, S.; GEMAN, D. Stochastic relaxation, gibbs distributions and the bayesian

restoration of images. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, New York, v. 6, n. 6, p. 721-741, 1984.

GERTLER, M.; KIYOTAKI, N.. Financial intermediation and credit policy in business cycle analysis. In: FRIEDMAN, B. M.; WOODFORD, M. Handbook of macroeconomics.

Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2010. v. 3, p. 547-99.

GERTLER, M.; KARADI, P. A model of unconventional monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics, Amsterdam, v. 58, n. 1, p. 17-34, 2011.

GILCHRIST, S. Financial markets and financial leverage in a two-country world economy. In: AHUMADA, L.; FUENTES, J.; LOAYZA, N.; SCHMIDT-HEBBEL, K. Central banking, analysis, and economic policies book series. Santiago: Central Bank of Chile, 2004. p. 27-58. GILCHRIST, S.; ORTIZ, A.; ZAKRAJŠEK, E. Credit risk and the macroeconomy: evidence from an estimated DSGE model. Boston: Boston University, 2009. Disponível em:

<http://www.federalreserve.gov/events/ conferences/fmmp2009/papers/Gilchrist-Ortiz-Zakrajsek.pdf>. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2014.

GILCHRIST, S.; HIMMELBERG, C. Investments, fundamentals and finance. In:

BERNANKE, B.; ROTEMBERG, J. NBER macreoconomics annual. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1998.

GILCHRIST, S.; ZAKRAJSEK, E. Credit spreads and business cycle fluctuations. May, 2011. (NBER Working Paper, n. 17021).

GILCHRIST, S.; ZAKRAJSEK, E. Credit supply shocks and economic activity in a financial accelerator model. rethinking finance: perspective on the crisis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation and The Century Foundation, 2012.

GILCHRIST, S.; HIMMELBERG, E. C. Evidence on the role of cash flow for investment. Journal of Monetary Economics, Amsterdam, v. 36, n. 3, p. 541-72, 1995.

GILCHRIST, S.; HAIRAULT, J.; KEMPF, H. Monetary policy and the financial accelerator in a monetary union. Germany: European Central Bank, 2002. (Working Paper, n. 175). GILCHRIST, S.; YANKOV, V.; ZAKRAJSEK, E. Credit market shocks and economic fluctuations. Journal of Monetary Economics, Amsterdam, v. 56, n. 4, p. 471-493, 2009. GREENSPAN, A. Economic Volatility. In: ECONOMIC SYMPOSIUM, Kansas City. 30 Aug. 2002. Disponível em: <http://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/

speeches/2002/20020830/default.htm>. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2014.

GUERRIERI, L.; IACOVIELLO, M.; MINETTI, R. Banks, sovereign debt and the

international transmission of business cycles. Cambridge: NBER International Seminar on Macroeconomics, 2012. (Working Paper, n.18303).

cycle and deal with systemic risks. Brasília: Central Bank of Brazil, Sep. 2012. (Working Paper Series, 292).

HE, Z.; KRISHNAMURTHY, A. A model of capital and crisis. 2011. Disponível em: <http://www.kellogg.northwestern.edu/faculty/krisharvind/ papers/capital.pdf >. Acesso em: 15 fev. 2014.

HELBLING, T.; HUIDROM, R.; KOSE M.; OTROK, C. Do credit shocks matter? a global perspective. Washington: International Monetary Fund, 2010. (IMF Working Papers, n.10/261).

IACOVIELLO, M. House prices, borrowing constraints and monetary policy in the business cycle. American Economic Review, Nashville, v. 95, n. 3, p. 739-64, 2005.

IACOVIELLO, M. Housing in DSGE models: findings and new directions. In: BANDT, O.; KNETSCH, T.; PEÑALOSA, J.; ZOLLINO, F. Housing markets in europe: a macroeconomic perspective. Berlin: Hidelberg: Springer-Verlag, 2010. p. 3-16.

______. Financial business cycle. 2014. Disponível em:

<http://old.econ.ucdavis.edu/faculty/kdsalyer/LECTURES/Ecn235a/PresentationPapersF11/Ia coviello_FBC.pdf>. Acesso em 14 fev. 2014.

IACOVIELLO, M.; MINETTI, R. International business cycles with domestic and foreign lenders. Journal of Monetary Economics, Amsterdam, v. 53, n. 8, p. 2267-2282, 2006. INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. Challenges Arising from Easy External Financial Conditions. In: ______. Regional economic outlook: Western Hemisphere. Washington: International Monetary Fund, 2010. Chap. 3.

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND. Global liquidity expansion: effects on receiving economies and policy response options. In: ______. Global financial stability report. Washington, 2002. Chap. 4.

JERMANN, U.; QUADRINI, V. Macroeconomic effects of financial shocks. American Economic Review, Nashville, v. 102, n. 1, p. 238-271, Feb. 2012.

JOYCE, M.; TONG, M.; WOODS, R. The United Kingdom's Quantitative Easing Policy: Design, Operation, and Impact. Quarterly Bulletin, London, Q3, p.200-212, Sep. 2011. KAMBER, G.; THONISSEN, C. Financial intermediation and the international business cycle: the case of small countries with large banks. New Zeland: Reserve Bank of New Zealand, 2012.

KILEY, M. The aggregate demand effects of short- and long-term interest rates. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2012. (Finance and Economics

Discussion Series, 2012-54)

KIM, C. J.; NELSON, C. State-space models with regime switching. Cambrige: MIT Press, 1999.

KISHAN, R.; OPIELA, T. Bank Size, Bank Capital, and the Bank Lending Channel. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Columbus, Ohio, v. 32, n. 1, p. 121-141, Feb. 2000.

KIYOTAKI, N.; MOORE, J. Credit cycles. Journal of Political Economy, Chicago, v. 105, n. 2, p. 211-248, 1997.

KOLLMANN, R.; ENDERS, Z.; MULLER, G. Global banking and international business cycles. European Economic Review, Amsterdam, v. 55, n. 3, 2011: 407-26.

LI, C.; WEI, M. Term structure modelling with supply factors and the federal reserve's large scale asset purchase programs. Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, 2012.

LIM, C. et al. Macroprudential policy: what instruments and how to use them? Washington: International Monetary Fund., Oct. 2011. (Work Paper, n. 11/238)

MCCULLEY, P.; TOLOUI, R. Chasing the neutral rate down: financial conditions, monetary policy, and the Taylor rule. Newport Beach: Global Central Bank Focus, Feb. 2008.

MEYER, L.; BOMFIM, A. Not your father's yield curve: modeling the impact of qe on treasury yields. St. Louis: Macroeconomic Advisers, 2012.

MEYER, L.; SACK, B. Updated monetary policy rules: why don't they explain recent monetary policy. St. Louis: Macroeconomic Advisors, Mar. 2008.

MISHKIN, F. How should we respond to asset price bubbles? Financial Institutions Center; Oliver Wyman Institute’s. 2008. Disponível em: <http://www.

federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/mishkin20080515a.htm>. Acesso em 15 fev. 2014. MODIGLIANI, F; M. MILLER. The Cost of Capital, Corporation Finance and The Theory of Investment. American Economic Review, Nashville, v. 48, n. 3, p. 261-267, 1958.

PSALIDA, L.; SUN, T. Does G-4 liquidity spill over? Washinton: International Monetary Fund, 2011. (IMF Working Paper, n. 11/237).

RAVN, M.; UHLIG, H. On adjusting the hodrick-prescott filter for the frequency of observations. The Review of Economics and Statistics, Cambridge, v. 84, n.2, p. 371-75, 2002.

SHIN, H. Adapting macroprudential approaches to emerging and developing economies. Washington: The World Bank, May 2011.

SIMS, C. Interpreting the macroeconomic time series facts: the effects of monetary policy. European Economic Review, Amsterdam, v. 36, n. 5, p. 975-1000, 1992.

SMETS, F.; WOUTERS, R. Shocks and frictions in us business cycles : a bayesian dsge approach. Frankfurt: European Central Bank, 2007. (Working Paper Series, 722). STOCK, J.; WATSON, M. Implications of dynamic factor models for VAR analysis. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, 2005.(NBER Working Paper, 11467). TAYLOR, J. Monetary policy and the state of the economy. Washington: The Committee on Financial Services, 2008.

TERRIER, G. Policy instruments to lean against the wind in Latin America. Washington: International Monetary Fund, 2011. (IMF Working Paper, WP/11/159).

UEDA, K. Banking globalization and international business cycles: Cross-border chained credit contracts and financial accelerators. Journal of International Economics, Amsterdam, v. 86, n. 1, p. 1-16, 2012.

VAN DEN HEUVEL, S. J. Does bank capital matter for monetary transmission. Economic Policy Review, New York, p. 1-7, May, 2002.

3 CREDIT SHOCKS AND MONETARY POLICY IN BRAZIL: A STRUCTURAL FAVAR APPROACH

3.1 Introduction

The severe recession that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 renewed the interest of academic professionals and policymakers in properly understanding the linkages between the financial sector and the real economy. A number of recent analyses have started to focus on the role played by financial intermediation as a channel to monetary policy. These studies find that disturbances originating in the credit sector played an important destabilizing role on the economic activity in the U.S. and other major nations during the great financial crisis.

Recent empirical studies by Boivin, Giannoni and Stevanovic (2012), Gilchrist and Zakrajsek (2012), and Gilchrist, Yankov and Zakrajsek (2009) have found that credit shocks reinforced the downturn of the business cycle in the U.S. during the 2007-2009 crisis. Helbling, Huidrom, Kose and Otrok (2010) showed that these shocks were influential in driving the great global recession, while Ahmadi (2009) found, through a model with time-varying parameters, that credit spread shocks have a much stronger macroeconomic effect in the U.S. during recessions than in normal times.

In this work, I try to shed some light on the credit sector’s role in the business cycle in Brazil through a Structural Factor Augmented Vector Autorregressive model (SFAVAR). The structural nature comes from the fact that the estimation strategy generates principal components that have a clear economic interpretation. To assess the transmission of the credit shocks to the economy, I generate impulse response functions and carry out a variance decomposition analysis. In addition, I obtain counterfactual simulations in order to quantify the contribution of these shocks to the dynamics of the economic activity, inflation and monetary policy pursued by the central bank.