FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO

LUCIA SALMONSON GUIMARÃES BARROS

HOPE, RISK PERCEPTION AND PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS

LUCIA SALMONSON GUIMARÃES BARROS

HOPE, RISK PERCEPTION AND PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS

Thesis presented to Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, for granting the title of Master in Business Administration.

Research Area: Marketing Strategy

Thesis Advisor: Prof. Dr. Delane Botelho

Barros, Lucia.

Hope, risk perception and propensity to indebtedness / Lucia Salmonson Guimarães Barros. - 2011.

139 f.

Orientador: Delane Botelho

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Expectativas racionais (Teoria econômica). 2. Percepção do risco. 3. Comportamento do consumidor. 4. Dívidas. I. Botelho, Delane. II. Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

LUCIA SALMONSON GUIMARÃES BARROS

HOPE, RISK PERCEPTION AND PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS

Thesis presented to Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo, Fundação Getúlio Vargas, for granting the title of Master in Business Administration

Research Area: Marketing Strategy

Approval date:

___/___/___

Thesis committee:

Prof. Dr. Delane Botelho (Thesis Advisor) Fundação Getúlio Vargas

Prof. Dr. José Mauro Hernandez Fundação Getúlio Vargas

To my parents Miriam and Leopoldo, and to my love Fernando, who have always showed support and a lot

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I feel very fortunate for the help and support I received from my family, friends, colleagues and professors, during this learning process. Without them, this journey would have not been possible.

First, I would like to thank my thesis advisor Delane Botelho for all the guidance I received during this process. His knowledge and encouragement not only guided this work, but was also an instrumental part of my formation as a marketing researcher.

Thanks to André Urdan and José Mauro Hernandez for their comments and

suggestions to my research project. And thanks to the professors and experts, Alda Almeida, Cristiano Lemke, Diógenes Bido, Eduardo Andrade, Eliane Brito, Felipe Zambaldi, José Afonso Mazzon, Luciano Thomé, Márcia Dantas, Rafael Goldszmidt, Roseli Porto and Valter Vieira, who kindly listened to me and gave me valuable advice to conduct this research.

I would like to thank Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPQ for the financial support received, which allowed me to dedicate my time to conduct this research.

I thank my colleagues at Centro Universitário FIEO for all the support and for helping me gathering students to participate on my field research.

Many thanks to my friends and family for their comprehension and a special thank to Fernando, who spent hours listening to how interesting the influence of hope on risk

perception and on propensity to indebtedness is. I also appreciate all the help received from my friends and family to gather people to be invited to participate on my experiment. And I would also like to thank all the people who agreed to participate on my research.

ABSTRACT

Hope is an important construct in marketing, once it is an antecedent of important marketing variables, such as trust, expectation and satisfaction (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Almeida, Mazzon & Botelho, 2007). Specifically, the literature suggests that hope can play an important influence on risk perception (Almeida, 2010, Almeida et al., 2007, Fleming, 2008, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005) and propensity to indebtedness (Fleming, 2008). Thus, this thesis aims to investigate the relations among hope, risk perception related to purchasing and consumption and propensity to indebtedness, by reviewing the existing literature and conducting two empirical researches. The first of them is a laboratory experiment, which accessed hope and risk perception of getting a mortgage loan. The second is a survey, investigating university students‘ propensity to get indebted to pay for their university tuition, analyzed through the method of Structural Equations Modeling (SEM). These studies found that hope seems to play an important role on propensity to indebtedness, as higher levels of hope predicted an increase in the propensity to accept the mortgage loan, independent of actual risks, and an increase in the propensity of college students to get indebted to pay for their studies. In addition, the first study suggests that hope may lead to a decrease in risk perception, which, however, has not been confirmed by the second study. Finally, this research offers some methodological contributions, due to the fact that it is the first study using an experimental method to study hope in Brazil and, worldwide, it is the first study investigating the relation among hope, risk perception and propensity to indebtedness, which proved to be important influences in consumer behavior.

SUMMARY

1. INTRODUCTION……….. 13

1.1. THEME………. 13

1.2. RESEARCH PROBLEM………...14

1.3 RELEVANCE……….14

1.4. STRUCTURE………16

2. THEORETICAL BACKGROUND………...17

2.1. WHAT HOPE IS ………...17

2.2. WHAT HOPE IS NOT………..24

2.2.1. EXPECTATIONS………...24

2.2.2. OPTIMISM……….25

2.2.3. CONFIDENCE ………27

2.2.4. FAITH……….27

2.2.5. DESIRE………...29

2.3. HOPE AND PURCHASE BEHAVIOR ………31

2.4. HOPE AND RISK PERCEPTION………33

2.5. HOPE AND PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS……….42

2.6. RISK PERCEPTION AND PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS……….46

2.7. HYPOTHESIS………...49

3. STUDY ONE………...51

3.1. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN AND PROCEDURE………...51

3.2. SCALES……….54

3.2.1. HOPE………..54

3.2.2. PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS………55

3.2.3. RESPONDENT‘S PERCEIVED RISK………..55

3.2.4. CHARACTER‘S PERCEIVED RISK………55

3.3. SAMPLE………56

3.4. RESULTS………..56

3.4.1. MANIPULATION CHECK………56

3.4.2. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE ON PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS…...57

3.4.3. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE ON RISK PERCEPTION………..58

3.4.5. THE INFLUENCE OF RISK ON RISK PERCEPTION………60

3.4.6. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE AND RISK PERCEPTION ON PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS………...61

3.4.7. SOME REASONS BEHIND THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE ON PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS……….63

3.4.8. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE AND RISK ON RISK PERCEPTION………..63

3.5. DISCUSSION………64

4. STUDY TWO………..66

4.1. RESEARCH PURPOSE ………66

4.2. QUESTIONNAIRE DESIGN………66

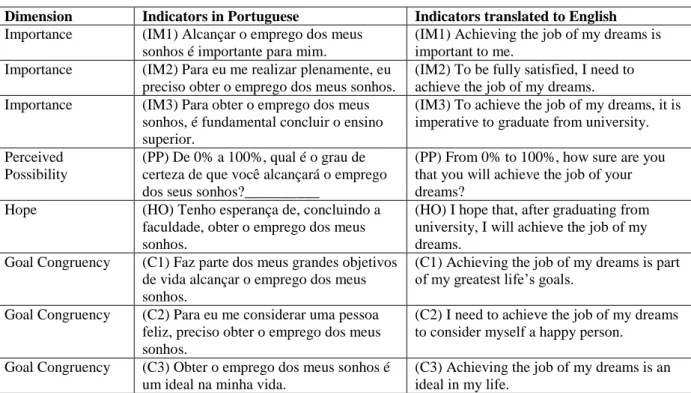

4.2.1. OPERATIONALIZATION OF STUDY VARIABLES……….67

4.2.2. SCALES………..67

4.3. SAMPLE………70

4.4. RESULTS………..70

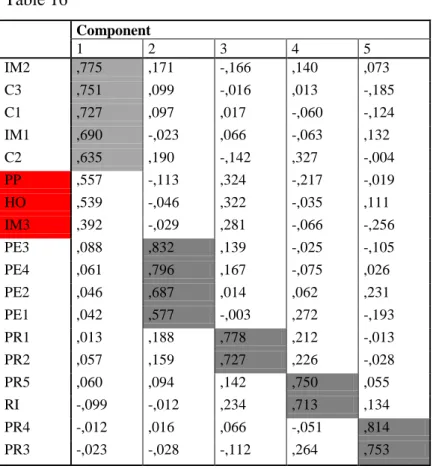

4.4.1. EXPLORATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS………..71

4.4.2. CONFIRMATORY FACTOR ANALYSIS………...73

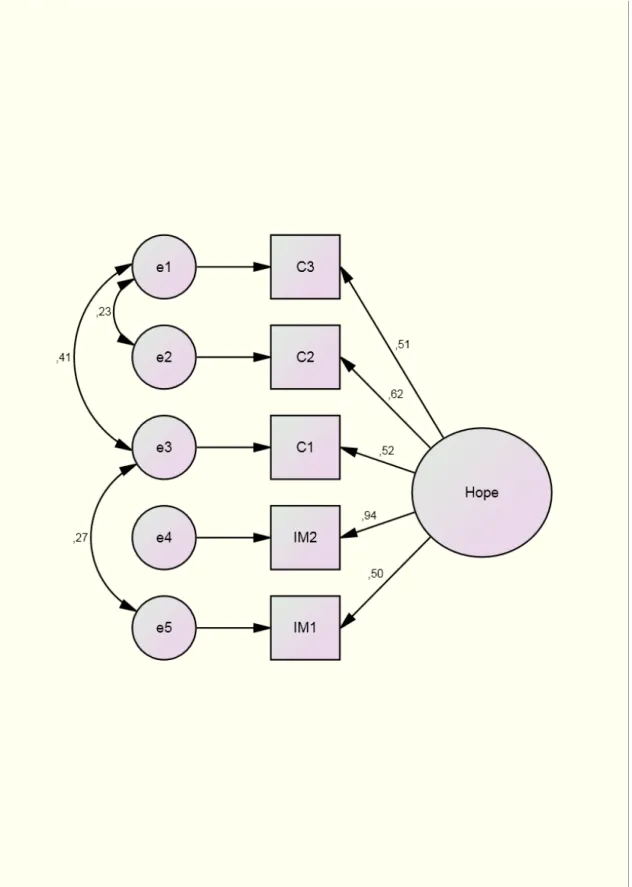

4.4.2.1. HOPE………73

4.4.2.2. PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS………..79

4.4.2.3. RISK PERCEPTION………..83

4.4.3. STRUCTURAL MODEL………...87

4.4.4. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE ON PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS…...89

4.4.5. THE INFLUENCE OF HOPE ON RISK PERCEPTION………..90

4.4.6. THE INFLUENCE OF RISK PERCEPTION ON PROPENSITY TO INDEBTEDNESS……….90

4.5. DISCUSSION………91

5. FINAL REMARKS……… 93

5.1. GENERAL DISCUSSION………93

5.2. STUDY LIMITATIONS ………94

5.3. MANAGERIAL AND PUBLIC POLICY IMPLICATIONS……….. 95

5.4. SUGGESTION FOR FUTURE STUDIES………95

REFERENCES………... 97

APPENDIX A –STIMULUS CONDITION 1………119

APPENDIX B –STIMULUS CONDITION 2………124

APPENDIX D –STIMULUS CONDITION 4………134

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

FIGURES

Figure 1. The Concept of Hope……….20

Figure 2. Key Risk Attenuation or Amplification Steps………...36

Figure 3. Theoretical Model of the Role of Hope on Risk Perception and Propensity to Indebtedness………..50

Figure 4. Propensity to Indebtedness‘ Means for the Four Experimental Conditions………..62

Figure 5. Model of confirmatory factor analysis of hope……….75

Figure 6. Model of confirmatory factor analysis of propensity to indebtedness………..80

Figure 7. Model of confirmatory factor analysis of risk perception……….84

Figure 8. Structural Model………87

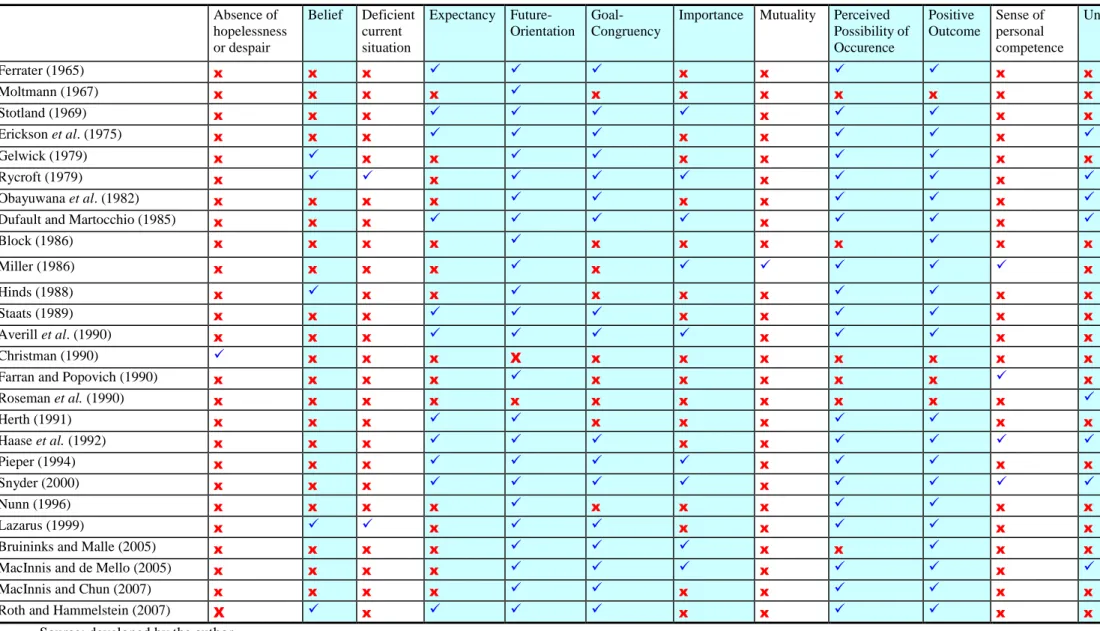

TABLES Table 1. Comparing the different definitions of hope………...19

Table 2. Commonalities and differences in the definitions of hope……….21

Table 3. Factors Influencing Risk Perception………...35

Table 4. Why Hope Should Reduce Consumers‘ Risk Perception………...39

Table 5. Factors associated with consumer debt behaviors………..43

Table 6. Experimental Design………...51

Table 7. Hope Manipulation……….52

Table 8. Risk‘s Manipulation………53

Table 9. Hope Manipulation Check………..57

Table 10. Risk Manipulation Check……….57

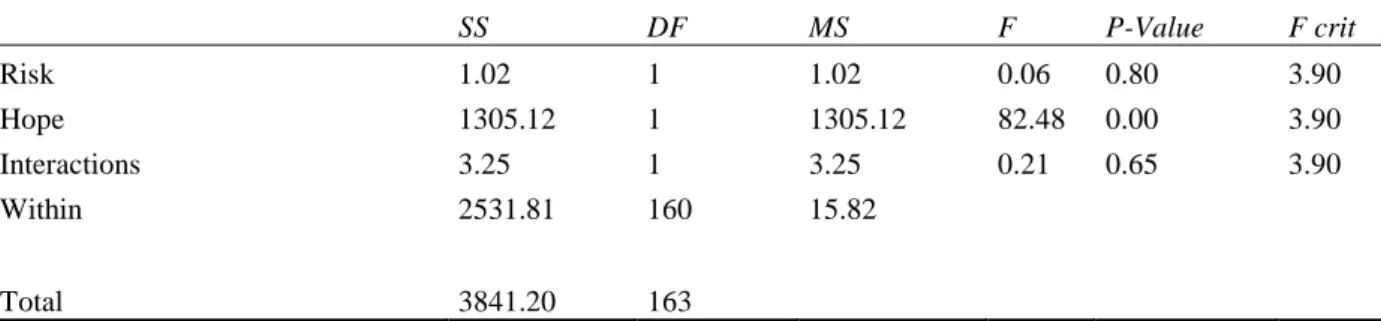

Table 11. Effect of Hope and Risk Perception on Propensity to Indebtedness……….61

Table 12. Effect of Hope and Risk on Risk Perception………64

Table 13. Hope Scale………68

Table 14. Propensity to Indebtedness Scale………..69

Table 15. Risk Perception Scale………...70

Table 16. Rotated Component Matrix………...72

Table 18. Hope Construct‘s Unstandardized Regression Weights………...76

Table 19.Hope Construct‘s Standardized Regression Weights……….76

Table 20. Hope Construct‘s Standardized Residual Covariances……….77

Table 21. Model fit for hope variable………...77

Table 22. Hope construct‘s reliability………...79

Table 23. Summary of Propensity to Indebtedness‘ Model‘s Parameters………79

Table 24. Propensity to Indebtedness Construct‘s Unstandardized Regression Weights…….81

Table 25. Propensity to Indebtedness Construct‘s Standardized Regression Weights……….81

Table 26. Propensity to Indebtedness Construct‘s Standardized Residual Covariances……..81

Table 27. Model fit for propensity to indebtedness variable ………....82

Table 28. Propensity to Indebtedness construct‘s reliability………82

Table 29. Summary of Risk Perception‘s Model‘s Parameters………83

Table 30. Risk Perception Construct‘s Unstandardized Regression Weights………...85

Table 31. Risk Perception Construct‘s Standardized Regression Weights………...85

Table 32. Risk Perception Construct‘s Standardized Residual Covariances………85

Table 33. Model fit for risk perception variable………...86

Table 34. Risk perception construct‘s reliability………..86

Table 35. Structural Model‘s Unstandardized Regression Weights……….88

Table 36. Structural Model‘s Standardized Regression Weights………..88

1.

INTRODUCTION

This initial chapter presents the theme of this thesis, the research problem and its relevance, in addition to the overall structure of this research paper.

1.1. Theme

In general, people hope everyday: when a man applies for a new job, he hopes to get it; when a mother sends her children to school, she hopes they will have a good future; when a person buys a lottery ticket, s/he hopes to win. Hope seems to be pervasive and because it can be found in everyone‘s mind, it has become an important construct in a number of fields, such as Philosophy (Bloch, 1986), Theology (Moltmann, 1967), Psychology (Aspinwall & Leaf, 2002, Averill, Catlin & Chon, 1990, Bruininks & Malle, 2005, F. B. Bryant & Cvengros, 2004, Lazarus, 1999, Roseman, Spindel & Jose, 1990, Snyder, 2000, Stotland, 1969), Nursery (Cutcliffe & Herth, 2002, Eliott, 2005, Herth, 1991, Kylmä & Vehvilainen-Julkunen, 1997, Morse & Penrod, 1999, C. H. Wang, 2000) and Medicine (Schneiderman, 2005, Wein, 2004).

Recently, hope was found to be also an important construct in marketing. Current research has suggested that hope is an antecedent of a number of important marketing variables, such as trust, expectation and satisfaction (A. R. D. Almeida, Mazzon & Botelho, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). However, despite its importance, little research has investigated hope in the marketing literature (de Mello & MacInnis, 2005, Fleming, 2008, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, Vanzellotti, 2007, V. A. Vieira, 2008).

One hopes when s/he has a goal (Snyder, 1994, Snyder, Cheavens & Sympson, 1997) and strongly believes it can be achieved. Goals are often related to consumption, either directly (e.g. to buy a car) or indirectly (e.g. to buy an airplane ticket to enjoy a wonderful vacation, Vanzellotti, 2007). So, hope has become increasingly important in the consumer behavior field.

relationship between hope and propensity to indebtedness has only been investigated by Fleming (2008)‘s qualitative research.

Now, it is important to test under an experimental design whether there is a causal relation between hope and propensity to indebtedness. It is also important to investigate if there are other variables mediating this relation, such as risk perception, what has already been suggested by MacInnis and de Mello (2005).

1.2. Research Problem

It has been suggested in the literature that high hope can lead to lower risk perception, which can lead consumers to harmful behaviors (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007, Fleming, 2008, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). For instance, a consumer who has a high level of hope can underestimate risks and be more prone to indebtedness (Fleming, 2008, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). Accordingly, hope has been shown to be an important element in the purchase of personal credit, which appears to be more likely to happen when consumers have income restrictions, what would make their current conditions much lower than the desired one (Clotfelter & Cook, 1989, Fleming, 2008, Hamilton, 1978, Lazarus, 1999).

Some authors suggest (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005) that risk perception in purchase decisions is lower when hope is strong. The reasons are that stronger levels of hope:

(1) increase the perception that the desired goal will happen,

(2) lower the perception of the likelihood of negative consequences, (3) and of their severities.

Even thought these authors have not empirically tested these propositions, those reasons make it reasonable for me to suppose that it is by lowering risk perception that hope influences the propensity to indebtedness.

risk perception would not necessarily lead to riskier behaviors (Becker, Nathanson, Drachman, & Kirscht, 1977, Langlie, 1977, Temoshok, Sweet & Zich, 1987).

So, this research aims to investigate the influence of hope on risk perception and on propensity to indebtedness. More specifically, I intend to answer the following questions: ―Does hope reduce risk perception?‖, ―Is risk perception an antecedent of propensity to indebtedness?‖, and ―Does hope increase consumers‘ propensity to indebtedness?‖.

1.3. Relevance

These research findings will contribute to existing literature in two ways:

(1) it will provide empirical evidence to a causal relation among hope, risk perception and propensity to indebtedness, which has already been pointed by theoretical and qualitative research;

(2) it will demonstrate whether it is possible to integrate two relations already found in the literature (hope and risk perception and hope and propensity to indebtedness) in a single model.

This research has also important managerial implications once:

(1) understanding such causes of debt contraction is especially important in the Brazilian context as Brazil is the country with the highest rate of instalment purchases in the world (58% of the population, from which 71% belongs to lower classes, Folha Online, 2009).

(2) if the hypotheses are confirmed, managers can use this information to stimulate hope if they want to increase sales through instalment payment.

(3) again, if the hypotheses are confirmed, managers should be careful in stimulating instalment purchases to people who would not be able to pay the instalments.

Moreover, this research has implications for public policies, due to the fact that preventing over-indebtedness should be a matter of concern for Brazilian government.

1.4. Structure

2.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This chapter reviews the literature about hope and its relation to purchase behavior, risk perception and propensity to indebtedness.

2.1. What Hope is

The concept of hope is important to a number of fields, such as Philosophy, Theology, Nursery, Medicine, and Marketing. However, due to conflicting definitions found in the literature, the concept of hope still need to be better developed (Eliott & Olver, 2007, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, Sigstad, Stray-Pedersen & Frøland, 2005, Vanzellotti, 2007) to be operationalized in an empirical research.

For instance, some scholars conceptualize hope as an emotion (A. R. Johnson & Stewart, 2004, Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994, Lazarus, 1999, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Nenkov, MacInnis & Morrin, 2009, Shaver et al., 1987, Vanzellotti, 2007) evoked in response to an uncertain but possible goal-congruent outcome. They understand that hope is a feeling of wanting something, but being unsure about the possibility of getting it (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Obayauwana et al., 1982, Rycroft, 1979).

In contrast, other scholars consider hope a cognitive set (Herth, 1991, Rubin, 2001, Snyder et al., 1991, 1996, 1997, Snyder, 1994, 1995, 2000, 2002) that is based on a

reciprocally-derived sense of successful agency and pathways. According to Snyder (1994, 1995, 2000, 2002), agency is ―the motivational component to propel people along their imagined routes to goals‖, while pathways are these imagined routes needed to achieve the desired goal. Together, they enhance each other, once ―they are continually affecting and being affected by each other as the goal pursuit process unfolds‖ (Snyder, 2000).

According to Day (1991), hope has both emotional and cognitive components. He explains that ‗hope involves a combination of belief, which has cognitive purport, and desire, which does not.‘ So, hope would be a construct which mixes a cognitive and an emotional component, at the same time.

that it is a reaction generated by an external environment‘s evaluation, which includes cognitions (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). In contrast, scholars who understand hope as a cognitive set explain that emotions arise from cognition related to hope, but are not hope per se (Ilardi et al. 2000, Snyder).

Author Definition What it is Field

Ferrater (1965) The perspective of having something with a probability of achieving it, resulting in a pleasure from the delightful future situation.

Cognition Philosophy

Moltmann (1967) The power to imagine the future. Not specified Theology

Stotland (1969) A necessary condition for action to achieve a goal that is a function of the perceived probability and perceived importance. Not specified Psychology Erickson, Post and Paige

(1975)

An expectancy that something desired will happen. Not specified Psychology

Gelwick (1979) A belief that what is desirable (goal congruent) and good is also possible. Cognition Theology Rycroft (1979) An attitude toward the future — a feeling or emotion about it that includes two features: we desire something we do not have;

and we desire something we believe we could or may gain.

Cognition Emotion

Psychology

Obayuwana et al. (1982) The feeling that what is desired is also possible or that events may turn out for the best. Emotion Medicine Dufault and Martocchio

(1985)

A multidimensional and dynamic life power characterized by a confident but uncertain expectation about achieving a personally significant goal.

Cognition Nursing

Block (1986) An anticipation of the future in a positive and liberating way. Emotion Philosophy

Miller (1986) An anticipation of a future which is good and based upon: mutuality (relationships with others), a sense of personal competence, coping ability, psychological well-being, purpose and meaning in life, as well as a sense of 'the possible'.

Cognition Nursing

Hinds (1988) A belief in one‘s own or one‘s relative‘s tomorrow. Not specified Nursing

Staats (1989) The expectation of desirable future events. Cognition Psychology

Averill et al. (1990) A positive valenced emotion, which arises when one appraises the probability of an attainment, which is important, as realistic. Emotion Psychology

Christman (1990) The absence of hopelessness or despair. Not specified Nursing

Farran and Popovich (1990) A subjective state that can influence realities yet to come. Not specified Nursing

Roseman et al. (1990) An emotion caused by an uncertain circumstance. Emotion Psychology

Herth (1991) Feelings and ideas, which have internal power from the certainty of positive expectancy. Cognition Nursing Haase, Britt, Conward,

Leidy, and Penn (1992)

An energized mental state involving feelings of uneasiness or uncertainty and characterized by a cognitive, action-oriented expectation that a positive future goal or outcome is possible.

Emotion Nursing

Pieper (1994) An emotion that occurs when what one is expecting is good signifying all that one longs for. Emotion Philosophy

Snyder (2000) A cognitive set comprising agency and pathways to reach goals. Cognition Psychology

Nunn (1996) A general tendency to construct and respond to the perceived future positively. Individual Difference

Psychology

Lazarus (1999) To believe that something positive, which does not presently apply to one's life, could still materialize. Emotion Psychology Bruininks and Malle (2005) An emotion that occurs when an individual is focused on an important positive future outcome. Emotion Psychology MacInnis and de Mello

(2005)

A positive valenced emotion which has three dimensions: goal congruency, uncertainty and importance. Emotion Marketing

MacInnis and Chun (2007) The degree to which one yearns for a positive and possible outcome. Emotion Marketing Roth and Hammelstein

(2007)

The expectancy that a possible event, which a person rates positively, will occur in the future. Emotion Psychology

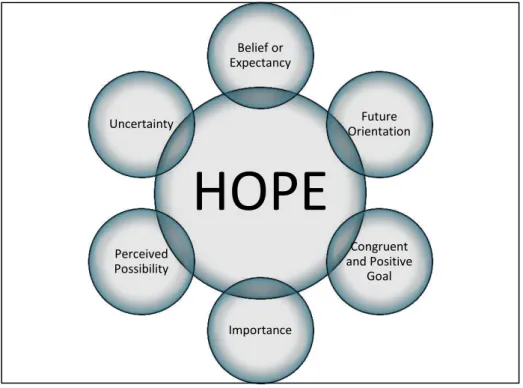

Due to this unclearness, the concept used here has been derived to what these definitions have in common: hope arises from the belief or expectancy1 that a future outcome2; which is positive and goal congruent3, important4, but uncertain5; can possibly be achieved6.

The characteristics of the concept of hope are illustrated in Figure 1 and the commonalities and differences in the definitions are illustrated in Table 2.

Figure 1. The Concept of Hope Source: developed by the author.

1 Ferrater Mora (1965), Stotland (1969), Erickson et al. (1975), Gelwick (1979), Rycroft (1979), Dufault and

Martocchio (1985), Hinds (1988), Staats (1989), Averill et al. (1990), Herth (1991), Snyder et al. (1991; 1996; 2000), Haase et al. (1992), Pieper (1994), Lazarus (1999), Roth and Hammelstein (2007).

2 Ferrater Mora (1965), Moltmann (1967), Stotland (1969), Erickson et al. (1975), Gelwick (1979), Rycroft

(1979), Obayuwana et al. (1982), Dufault and Martocchio (1985), Block (1986), Miller (1986), Hinds (1988), Staats (1989), Averill et al. (1990), Farran and Popovich (1990), Herth (1991), Snyder et al. (1991; 1996; 2000), Haase et al. (1992), Pieper (1994), Nunn (1996), Lazarus (1999), Bruininks and Malle (2005), MacInnis and de Mello (2005), MacInnis and Chun (2007), Roth and Hammelstein (2007).

3 Ferrater Mora (1965), Stotland (1969), Erickson et al. (1975), Gelwick (1979), Rycroft (1979), Obayuwana et

al. (1982), Dufault and Martocchio (1985), Block (1986), Miller (1986), Hinds (1988), Staats (1989), Averill et al. (1990), Herth (1991), Haase et al. (1992), Pieper (1994), Snyder et al. (1991; 1996; 2000), Nunn (1996), Lazarus (1999), Bruininks and Malle (2005), MacInnis and de Mello (2005), MacInnis and Chun (2007), Roth and Hammelstein (2007).

4 Stotland (1969), Rycroft (1979), Dufault and Martocchio (1985), Miller (1986), Averill et al. (1990), Pieper

(1994), Snyder (2000), Bruininks and Malle (2005), MacInnis and de Mello (2005).

5 Erickson et al. (1975), Rycroft (1979), Obayuwana et al. (1982), Dufault and Martocchio (1985), Roseman et

al. (1990), Haase et al. (1992), Snyder et al. (1991; 1996; 2000), MacInnis and de Mello (2005).

6 Ferrater Mora (1965), Stotland (1969), Erickson et al. (1975), Gelwick (1979), Rycroft (1979), Obayuwana et

al. (1982), Dufault and Martocchio (1985), Miller (1986), Hinds (1988), Staats (1989), Averill et al. (1990), Herth (1991), Haase et al. (1992), Pieper (1994), Snyder et al. (1991; 1996; 2000), Nunn (1996), Lazarus (1999), MacInnis and de Mello (2005), MacInnis and Chun (2007), Roth and Hammelstein (2007).

Table 2. Commonalities and differences in the definitions of hope

Absence of hopelessness or despair

Belief Deficient current situation

Expectancy Future-Orientation

Goal-Congruency

Importance Mutuality Perceived Possibility of Occurence Positive Outcome Sense of personal competence Uncertainty

Ferrater (1965) x x x x x x x

Moltmann (1967) x x x x x x x x x x x

Stotland (1969) x x x x x x

Erickson et al. (1975) x x x x x x

Gelwick (1979) x x x x x x x

Rycroft (1979) x x x x

Obayuwana et al. (1982) x x x x x x x

Dufault and Martocchio (1985) x x x x x

Block (1986) x x x x x x x x x x

Miller (1986) x x x x x x

Hinds (1988) x x x x x x x x

Staats (1989) x x x x x x x

Averill et al. (1990) x x x x x x

Christman (1990) x x x X x x x x x x x

Farran and Popovich (1990) x x x x x x x x x x

Roseman et al. (1990) x x x x x x x x x x x

Herth (1991) x x x x x x x x

Haase et al. (1992) x x x x x

Pieper (1994) x x x x x x

Snyder (2000) x x x x

Nunn (1996) x x x x x x x x x

Lazarus (1999) x x x x x x

Bruininks and Malle (2005) x x x x x x x x

MacInnis and de Mello (2005) x x x x x x

MacInnis and Chun (2007) x x x x x x x x

Roth and Hammelstein (2007) X x x x x x

Uncertainty is the first characteristic of hope‘s concept. It is important in the hope growth process and it helps to differentiate hope from other positive states, such as joy (Roseman, 1984, Roseman et al., 1990). The reason behind it is that goals with 100% of probability of attainment (e.g. it is certainly going to happen) do not require hope, while goals with 0% of probability (e.g. it is certainly not going to happen) do not produce hope (Averill et al, 1990). For example, I do not hope to buy food when I am at the grocery store, because I am certain that I will do so. I also do not hope to buy a Ferrari tomorrow because I am certain that this is something I will not do. Uncertainty appears when one perceives barriers to the desired goals (Snyder, 2000, 2002).

In addition, uncertainty is part of the hope‘s concept due to the fact that hope is future oriented - the second characteristic of the concept - which means that it focuses on outcomes that have not happened yet, which is agreed by most authors. In this sense, hope seems to be related to a way of seeing oneself not the way s/he really is, but how s/he would like to be, which was conceptualized by Markus and Nurius (1986) as ‗possible-selves‘. Moreover, some authors suggest that hope is not only a matter of looking to the future, but it is already a way of engaging purposely with the present to achieve the desired future (Heidegger, 1962, Snyder, 2000, Snyder et al., 1991).

Thus, hope can be described as a belief or a general expectancy, which is the third characteristic of its concept. The reason for it is that hope arises with an evaluation of

possibility, not probability. A person can hope even when the likelihood of a certain result is very low. There are cases in which people have demonstrated hope in overcoming serious diseases even in extreme situations (Lazarus, 1999), meaning that some people interpret even extremely low probabilities of surviving as an evidence of the recuperation‘s possibility (E. S. Taylor & Brown, 1988; E. S. Taylor, Kemeny, Reed, Brower & Gruenwald, 2000). This evaluation of possibility was called by Bluhm (2006) as subjective probability.

The fourth characteristic of hope‘s concept is the congruency with positive goals. It means that neither negative outcomes nor outcomes contrary to our wishes will produce hope. According to MacInnis and de Mello (2005), in a benign environment, goal congruency means that a favorable outcome could occur, while in an aversive or threatening environment, it means that a negative outcome could be avoided or solved. For example, I might hope for getting a salary raise (favorable outcome in a benign environment) or that I will not have cancer (avoiding a negative outcome in a threatening environment).

to these authors, yearning is ‗the degree of longing for a goal congruent outcome‘. Thus, there is no hope for ordinary subjects and the level of hope can vary according to the will

(MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). For this reason, people will not feel hope when they do not want to reach their goal anymore (Averill et al. 1990). For instance, I may hope to buy the latest computer, but when a new version is launched, I do not hope to buy that computer any longer.

The greater the importance given to an outcome, the greater its value and the more severe the consequences of a failure. This importance leads the person to mentally draw pathways to achieve the desired outcome, being capable of visualizing her(him)self in the future, in which current difficulties will be overcome (Snyder, 2000). Hope works as an incentive, an extra strength for the person to reach positive outcomes for the desired goals (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007). For its motivational characteristic, hope seems to be relevant, capable of influencing attitudes and purchase behavior (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005).

Finally, the sixth characteristic is the perceived possibility of the outcome. When one perceives a situation as possible, s/he starts to believe or to expect a certain result, which was already mentioned as hope‘s second characteristic. For example, when an ad suggest

possibilities in the product (‗Now, you can lose weight on your own terms‘), it provokes hope (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005).

Because of all these characteristics, contrary to Christman (1990), hope seems to be more than just the absence of hopelessness. For instance, I may not hope that I will find a new job not because I feel hopeless about it, but because it is just not important.

Nenkov, MacInnis & Morrin (2009) do not consider expectancy as part of hope, but as a different concept called hopefulness. However, because a number of authors consider it as part of hope (Averill et al., 1990, Dufault & Martocchio, 1985, Erickson et al., 1975, Ferrater, 1965, Haase et al., 1992, Herth, 1991, 1965, Pieper, 1994, Roth & Hammelstein, 2007, Snyder et al., 1991, 1996, 2000, Staats, 1989, Stotland, 1969), I understand that hopefulness, as described by Nenkov et al. (2009), is a characteristic of the concept of hope.

It is not a purpose of this thesis to define hope as either an emotion or cognition. According to A. R. D. Almeida (2010), I understand hope as a feeling, having both emotional and cognitive aspects.

2.2. What Hope is Not

When thinking about hope, a lot of words come to mind, such as: expectations, optimism, confidence, faith and desire. For this reason, to better understand the concept of hope, it is important to understand the concept of all these other constructs which are often related to it and to each other; and to know how to differentiate one from the others.

2.2.1. Expectations

Unlike hope, the expectation is a construct already extensively explored in the marketing literature (Fleming, 2008). Expectations are the perception of likelihood that reflects the perceived probability that an outcome will be achieved (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Vanzellotti, 2007). Although earlier scholars have defined hope as a synonym of expectations, I agree with the ones who advocate that these constructs are different for three reasons.

First, there is hope only when the outcome is goal congruent, while there are expectations for goal congruent, incongruent and irrelevant outcomes (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). For example, a person can have expectations about losing his/her job, but still hope to keep it (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007).

Second, there is only hope for important outcomes; while there can be expectations for ordinary ones (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). It seems that talking about hope involves more passion (Belk, Ger & Askegaard, 1997, 2003). MacInnis and Chun (2007) illustrate it saying that ‗one may have strong expectations that one‘s pen will write without smudging, but it is doubtful that feelings of hope over the same outcome are intense‘. Consistently, Vanzellotti (2007) found in her interviews that the word ‗expectations‘ instead of ‗hope‘ was used for more realistic and less passionate examples.

reason behind it is that hope is ‗linked with general uncertainty, not a specific expectation level, as one can also hope for things that are uncertain but either expected or unexpected (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005).

Even though he could not empirically confirm this hypothesis, Vieira (2008) suggests that expectations can be an antecedent of hope. His argumentation seems reasonable, once expectations provide the sense that an outcome is possible, which consequentially enhances hope. A. R. D. Almeida (2010) agrees that hope and expectations are different constructs, but she empirically found that hope is an antecedent of expectations.

Consistently, Calman (1984) explains that a good quality of life occurs when hope matches expectations, while when a goal that constitutes an expectation central to quality of life is severely threatened, the hopeful person may spend a large amount of energy fiercely defending that hope.

2.2.2. Optimism

According to Seligman (1991), optimism is a personality trait that makes one assume that negative outcomes are momentous and their causes are external. For this reason, a person who is optimistic has generalized joy-producing outcomes expectancies (Chang, 1998,

Scheier & Carver, 1985, Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, & Connor, 1987) and copes well with challenges of life (Carver, Scheier & Weintraub, 1989). Although both constructs are related to future oriented positive expectancies (Snyder et al., 2001) and are predictors of better coping strategies (Snyder, 2000), hope and optimism have important differences.

First, while optimism produces generalized expectations, for hope to exist, there must be a specific goal (F. B. Bryant & Cvengros, 2004, Bruininks & Malle, 2005, Snyder, 2000). This means that if I am an optimistic person, I will believe that ‗everything is going to be all right‘, while I hope that specific outcomes such as getting a new job or losing weight will happen. Also, hope is something experienced by everyone, in different parts of their lives, while only some people are optimistic. To illustrate it, Lazarus (1999) said that he is ‗a pessimist who hopes.‘

I join the gym or start a new diet. As optimism produces generalized expectations, the same pattern of behaviors does not happen.

The third difference is that while hope has a component of desire (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007, Bluhm, 2006, MacInnis and Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005), optimism appears to be separate from the ―wanting‖ states (Bruininks & Malle, 2005). The reason for that may be again the difference between general and specific outcomes, each being generated by one of these constructs.

Bruininks and Malle (2005) explain that hope and optimism also differ in how they are related to personal control. They illustrate it by contrasting the example of a student who may be optimistic about doing well on a test because she knows that she can study for it

beforehand with the case of hoping to recover from the flu, in which the person probably does not have the ability to heal himself and so experiences hope that he will recover quickly.

Another difference is the cause of hope and optimism. While hope can be caused by outcome congruent information (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005), optimism seems not to be caused by specific events (Bruininks & Malle, 2005). They explain the reason underlying this to be that optimism is sometimes referred to as a personality trait; thus, it would exist

independently from a particular situation.

In addition, Deneen (1999) explains that hope is a construct often related to faith, unlike optimism, which is just ‗the belief that things will improve‘. This difference seems reasonable, considering that hope is part of the values from many religions (N. H. Smith, 2005). Van Ness and Larson (2002) even suggested that hope can be a mediator between religiousness and mental health.

Finally, hope involves a perception of the possibility of negatives outcomes, because of the uncertainty characteristic. In contrast, optimism often excludes or weakens this

possibility (Lazarus, 1999). In other words, if I think that ‗everything is going to be all right‘, I do not think that something wrong might happen. But if I hope to get a new job, I think of the possibility of not getting it, which makes me try harder. The reason for it is that, unlike optimism, hope includes a felling of self-efficacy (Snyder, 2000). As a consequence, Bruininks and Malle (2005) suggest that optimism can be better described in terms of an individual perceiving an outcome as likely to occur than hope.

(2001), in a study of women with breast cancer, found something different: that these two variables were not even correlated.

2.2.3. Confidence

Confidence can be conceptualized as the perceived certainty about someone‘s future behavior (Das & Teng, 1998) or that some expectations will not be disappointed (Luhmann, 2000). According to this author, it ‗emerges in situations characterized by contingency and danger, which makes it meaningful to reflect on pre-adaptive and protective measures‘.

Consistently, self-confidence is the confidence in someone‘s own abilities (Bénabou & Tirole, 2002). Like hope, both confidence and self-confidence are related to positive expectations; however their concepts have the following differences.

Even though both hope and confidence arise from future uncertain situations, the uncertainty aspect seems stronger for hope (MacInnis & Chun, 2007). When one is confident that something will happen, s/he does not think about the likelihood of it not happening. If this person hopes for something, in contrast, s/he wants it to happen, but is aware of the possibility of an undesired outcome.

In addition, Howard and Sheth (1969) proposed that confidence is the inverse of perceived risk. Thus, confidence and risk perception should be the two polarities of the same construct. Here, I hypothesize a negative causal relation between hope and risk perception. Different from confidence, this means that hope and risk perception are different constructs, even though they are related.

2.2.4. Faith

The first difference is that, unlike faith, hope can be found in non-religious contexts (MacInnis & Chun, 2007). For instance, I may hope to go to heaven after death (religious context), but I can also hope to win the lottery (non-religious context). Specifically, hope in purchases and consumption seems to be seldom related to religion, but to the achievement of desired outcomes from a number of different natures.

The second difference is the role hope plays as an antecedent of different affective states. For example, Ai et al. (2005) found stronger correlations between hope and depression and between hope and anxiety than between faith and the same constructs.

The third difference concerns the time framing in which these states happen. While hope is always future oriented, faith can be future, present or past oriented. For instance, I can have faith that Jesus existed (past), that God is protecting me (present) or that I will go to heaven after death (future).

The fourth difference is related to yearning. While someone must want an outcome to happen when s/he has hope, the same does not happen with faith (Vanzellotti, 2007). The reason for it is that faith does not require an outcome (Vanzellotti, 2007). For instance, I may have faith in God and not want, wish, desire, yearn, expect or hope for any outcome to happen.

The fifth difference concerns the reaction towards these states. Vanzellotti (2007) found that while hope is action-driven, faith seems to lead to more passive behaviors. In her research, different from hope, a person who has faith has been described as someone reactive, who waits passively for the outcome to happen. This person seemed to leave his

responsibilities, giving them to someone else.

Another difference regards the uncertainty level. When a person has faith, s/he strongly believes that ‗everything is going to be all right‘, which shows a high degree of certainty. Differently, even when hope is strong, the person is still unsure about the

occurrence of the future outcome (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, Vanzellotti, 2007, Will, 2009). Some scholars consider faith as a part of hope (Lohachiwa, 2005), signalling that hope is a broader construct. One example is a research from Bays (2001), which found that faith in God was one of twelve elements in hope. Consistently, Farran, Salloway and Clark (1995) described hope as having four different processes: experiential, spiritual, rational thought and relational. Faith is part only of the spiritual one.

Dominican village. Another example is a study from Herth (1993), which found that faith in religion increased the level of hope of elderly people.

There are others, such as Block (1986), Tiger (1979), Benzein and Saveman (1998), H. Miyazaki (2004) and Will (2009), who consider hope to be a source of faith. In his point of view, imagined nonhuman agents such as God are manifestations of hope, which in turn, creates faith. Deneen (1999) shares the same opinion, explaining that hope is a refraction of faith in a transcendent entity.

Finally, someone‘s hope can be strengthened or weakened due to environmental clues, while the same does not happen with faith. On the contrary, faith seems to remain unaltered due to a belief in an inner force, such as God. In other words, hope is influenced by the environment while faith seems to depend on individual values (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005).

2.2.5. Desire

As said before, for hope to exist, the outcome must be important, which means that this outcome has to be desired beforehand. Because hope and desire are always related (A. R. D. Almeida, 2010, A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007, Averill et al., 1990, Belk et al., 1997, 2003, Downie, 1963, Erickson et al., 1975, Fleming, 2008, Frijda, 1986, Herth, 1989, Lazarus, 1991, 1999, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Menninger, 1959, Obayauwana et al., 1982, Roseman, 1991, Roseman et al., 1990, Rycroft, 1979, Shaver et al., 1987, C.A. Smith & Ellsworth, 1985, Snyder, 1994, 2000, Snyder et al., 1996, 1997, Stotland, 1969, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, Vanzellotti, 2007), it is not always easy to recognize if a certain behavior is guided by desire alone or if hope is also there. However, they are different (Bruininks & Malle, 2005) and it is important to understand the differences between these two constructs.

through dreams (Belk et al., 2003). For this reason, it seems reasonable that hope is more action-driven than desire alone (Snyder et al., 1991).

The second difference regards time framing. While hope is future oriented, desire can be also past and present oriented (Averill et al., 1990, Bruininks and Malle, 2005). For instance, I can desire to have chosen medical school instead of business school, but I do not hope I have made a different choice in the past. In this sense, desire can also be related to other affective states such as regret. I can also desire for something in the present, such as eating a chocolate cake.

This example may help me to explain the third difference, which is related to uncertainty. As mentioned before, hope needs a minimum degree of uncertainty to exist. Unlike that, I can desire something I am 100% certain that will happen. Again, if I have a chocolate cake in my fridge, I can desire to eat a piece of it, but I will not hope to do so, because I am certain I can do it. Consistent with it, Roseman et al. (1990) explained that ‗wanting and desire were elicited when conditions were judged as favorable for realizing the outcome, whereas hope was elicited when conditions were judged as difficult but the outcome was still attainable.

The fourth difference is about broadness. According to Slegers (2006), while hope is broad (e.g. I hope to lose weight and for this I can eat less, go to the gym or take medicines), desire is narrow (I want to run and nothing else will satisfy my desire for it). The author explains that desire is not open to options. Hope, in contrast, has to be broader because of the sense of uncertainty.

The fifth difference is related to inconsistent actions after them. While desire may lead to some inconsistent and even immoral behaviors (e.g. eating caloric food, cheating a partner, committing violence against someone) (Belk et al., 1997, 2003, Karlsson, 2003,), hope for desirable outcomes have consumers resist and avoid these behaviors (e.g. hope for losing weight, hope for a happy marriage, hope for true friendships) (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005).

Another difference is that hope seems to be related to more important outcomes than desire (Averill et al., 1990, Bruininks & Malle, 2005, Vanzellotti, 2007). Averill et al. (1990) also found differences in the nature of the outcome, ‗with hoped-for outcomes described as less materialistic, socially more acceptable, more enduring and/or in the future, and more abstract and/or intangible than the objects of wants or desire‘.

Thus, hope seems to be the next step after desire (Ellsworth and Smith, 1988, Lazarus, 1991; 1999). Belk et al., (2003) explained that desire follows a cycle. In this cycle, first one recognizes a lack; then, s/he desires to have an outcome; after that s/he hopes for it; then s/he acts to get it; and after achieving it, this process restarts.

2.3. Hope and Purchase Behavior

The purchase and consumption of goods and services are part of people‘s goals. People hope to look better, to feel more attractive, to lose weight, to have a beautiful house, to relax, etc. (MacInnis and de Mello, 2005). In this context, it seems reasonable that hope appears as an antecedent of a number of purchase and consumption behaviors. Consumption can be either the goal per se (e.g. to buy a beautiful house) or the means to achieve a greater goal (e.g. to buy cosmetics to feel more attractive) (MacInnis and de Mello, 2005, Vanzellotti, 2007).

In Rossiter and Foxall (2008)‘s theory, hope appears among the intervenient variables which affect consumers‘ response. For this reason, it is considered a positive reinforcement tool in a process of motivational incentive. In other words, hope would encourage consumers‘ action, which can be the evaluation, choice and purchase of several products.

In addition, hope can affect the way consumers process and understand advertisings. There is hope only when the goal is important, so when hope is high, involvement is also high. Considering that in situations of high involvement, people process information in a more systematic way, rather than using heuristic (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005), when hope is high, the way of processing information should switch from a heuristic to a systematic one.

This would make people pay more attention in the message‘s strength rather than in some background information, such as music or pictures (Eagly & Chaiken, 1993, Petty & Cacioppo, 1983). However, because there is a need for people to maintain their hope level, instead being affected by the message‘s strength, they should be affected by its goal congruency.

So, when with high hope, people tend to systematically look for congruent

This relation seems reasonable and hope messages are used for the promotion of many products. For instance, anti-winkles cosmetics‘ advertisings enhance hope of achieving young skin for a longer time (Vanzellotti, 2007). There are also a number of advertisings targeting the low-income consumer, which links the purchase of many products to the idea of dreams coming true (Fleming, 2008).

Another reason for hope to enhance attitudes towards advertising is that positive emotions impacts favorably in attitudes towards messages, independently of their strength (Bless, Mackie & Schwarz, 1992). Even though it is not clear whether hope is an emotion or not, even the scholars who defend its cognitive nature agrees that hope evokes positive emotions (Snyder, 2000).

MacInnis and de Mello (2005) and MacInnis and Chun (2007) explained that due to the fact that hope is an important antecedent of purchases and consumption, market tactics can evoke and increase consumer‘s hope. To do so, advertised messages should either: (1) suggest possibilities in the product; (2) suggest possibilities in the person; (3) suggest

possibilities in the process; (4) enhance perceived importance; (5) enhance the goal congruity of the outcome; (6) evoke positive fantasy imagery; (7) suggest that a product or service can resolve an approach avoidance conflict; (8) link usage of the product or service with higher order goals; or (9) stress achievement of the goal by similar other and aspirational groups.

Some of these tactics have already been tested by the literature. For example, by enhancing the goal congruity of the outcome, health claims were found to evoke more hope than nutrition information in food advertising (T. Wang, 2007). Hope could also be evoked from suggesting possibilities in the product, which could be preventing from a negative state or achieving a positive state (Poels & Dewitte, 2007).

Not only hope was found to lead to an increased attitude towards advertising, but T. Wang (2007) also found hope to be an antecedent of both product attitude and purchasing intention, strengthening the role hopes play in consumer and product behavior.

In addition, hope can be understood as a motivational state, which encourages people to act to achieve the desired and important goal (Snyder, 2000). It means that hope acts as an antecedent of planned purchases, which involves an effort (in contrast, for instance, with impulse purchases).

Moreover, as hope is future oriented, it is possible that when consumers look for specific products, they think about their relevance to their hoped self instead of their actual self (MacInnis & Chun, 2007). In other words, there may be a tendency for one to buy a product for what s/he hopes to be than for what s/he actually is. One example is a person who buys a new laptop because s/he hopes to need it for a new job which is still uncertain.

Finally, in purchase situations, hope was said to be an antecedent of some other variables, such as attitude (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, T. Wang, 2007), trust (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Vieira, 2008), expectations (A. R. D. Almeida et al., 2007) and satisfaction (MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). For this reason, it is reasonable to understand that hope is capable of influencing consumers‘ evaluation and choice.

2.4. Hope and Risk Perception

Risk can be conceptualized as the probability of events and the magnitude of their specific consequences (Bettman, 1973, Kaplan, Syzbillo & Jacoby, 1974, Kasperson et al., 1988, Lopes, 1995, J. W. Taylor, 1974). Thus, a very risky situation should involve both: high probability and severe consequences. In addition, a situation which is very likely to happen, but does not produce severe consequences should be perceived as equally risky as another situation, which is not very likely to happen, but produces severe consequences. However, the authors explain that the society uses a number of mechanisms to change the way risk

information is processed and, as a consequence, perceived. Thus, it is important to understand how risk perception (or perceived risk) is formed.

The concept of perceived risk was first explained by Bauer (1960) as a psychological, and subjective construct to explain some phenomena such as information seeking and brand loyalty. It reflects the extent to which a product or service is perceived to have uncertain, personal, and negative consequences (Bauer, 1960, M. Cunningham, 1979, M. S. Johnson, Sivadas & Garbarino, 2008, Solomon, 1999, Stone & Grönhaug, 1993). For example, A. D. Miyazaki and Fernandez (2001) argued that a positive feedback or personal experience could lower the perceived risk of buying online, which would let consumers to feel more

Risk perception is associated to the anticipation of negative outcomes (S. M. Cunningham, 1967, M. S. Johnson et al., 2008, Stone & Grönhaug, 1993) and can be explained under a number of different approaches (Sjöberg 2000). According to the author, technical risk is not the only factor in accounting for perceived risk.

According to Bettman (1973) perceived risk is composed by two components: inherent risk and handled risk. The author explains that inherent risk is the latent risk a product holds, while latent risk is the amount of conflict the product is able to arise when the consumer chooses a brand. J. W. Taylor (1974) complements, explaining that the two aspects that form perceived risk is the uncertainty about the outcome and the uncertainty about its

consequences.

Table 3

Factors Influencing Risk Perception

Factors References

Gender Barke, Jenkins-Smith, and Slovic (1997), Brody (1984), Gardner and Gould (1989), Steger and Witt (1989), Gwartney-Gibbs and Lach (1991), Stern, Dietz and Kalof (1993), Gutteling and Wiegman (1993), Slovic (1997), Slovic, Malmfors, Mertz, Neil and Purchase (1997), Weber, Blais and Betz (2002), Garbarino and Strahilevitz (2004).

Culture Douglas and Wildavsky (1982), Slovic (1997).

Risk Communication Combs and Slovic (1979), Fischhoff (1995), Clow, Baack and Fogliasso (1998), Chandran and Menon (2004), Chen (2007). Heuristics and biases Kahneman, Slovic and Tversky (1982), Slovic (1987).

Outcome‘s framing Tversky and Kahneman (1981), Kahneman and Tversky (1984), M. B. Brewer and Kramer (1986), van Schie and van der Pligt (1995), Highhouse and Yuce (1996), Raghubir and Menon (1998), Menon, Block, and Ramanathan (2002), Chandran and Menon (2004). Availability Combs and Slovic (1979), Sjöberg (2000).

Representativeness Tversky and Kahneman (1974)

Voluntariness Starr (1969)

Personality traits Farley (1986), Weber (1997, 1998). Familiarity with the hazard De Fleur (1966)

Information source Kasperson et al. (1988), Garbarino and Strahilevitz (2004). Personal experience Kasperson et al. (1988), Rothman and Salovey (1997). Information transfer about the risk Kasperson et al. (1988)

Social context Bandura (1973, 1977), Weber (1997, 1998), Kasperson et al. (1988). Catastrophic potential Slovic, Fischhoff, and Lichtenstein (1982), Renn (1985).

Effects for future generations Slovic (1980)

Attitude Sjöberg (2000)

Risk sensitivity Sjöberg (2000)

Risk target (the person itself or others) Slovic (1998), Sjöberg (2000). Time (consequences for the near or

distant future)

Chandran and Menon (2004)

Perceived controllability Slovic 1980, March and Shapira (1987).

Vulnerability Hayenhjelm (2006)

Involvement Rothman and Salovey (1997)

Mood and Positive Emotions Rothman and Salovey (1997), Chaudhuri (2002), Chandran and Menon, (2004).

Expectations Hassan, Kunz, Pearson and Mohamed (2006) Numeracy (how facile people are with

basic probability and mathematical concepts)

Lipkus, Samsa and Rimer (2001)

Specific fear Sjöberg (2000)

Source: developed by the author

Among these factors, availability is one of the most cited (Sjöberg, 2000). For this reason, according to Combs and Slovic (1979), frequent media exposure gives rise to a high level of perceived risk. In contrast, Clow et al. (1998) explain that ads‘ messages can give clues to reduce consumers‘ perception of risk.

belts, or eating highly carcinogenic aflatoxins in peanut butter. They call this distortion in perception as a social attenuation of the risk, which leads to an underresponse, as a

consequence. To better explain this distortion in perception, these authors propose a process by which individuals engage in a risk attenuation (or amplification) process, which is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Key Risk Attenuation or Amplification Steps

Source: developed by the author based on Kasperson et al. (1988).

Risk is a construct which has a multidimensional nature (Jacoby & Kaplan, 1972), involving economic, social, psychological, or physical domains (Bauer, 1960, Dholakia, 1997, M. S. Johnson et al., 2008, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis, de Mello & Patrick, 2004, Mitchell & Harris, 2005, Solomon, 1999) and the perceived risk in one domain can change the perceived risk in the other (A. R. D. Almeida & Botelho, 2008). For instance, the authors explain that non-financial risks can make financial risks to be perceived as higher.

Even these domains can be divided in sub-domains, depending on the situation. For instance, the economic or financial domain is often seen in a different way due to the

Risk perception has been recognized by the marketing literature as an important factor that would strongly influence consumer behavior (A. R. D. Almeida, 2010, Laroche, Bergeron & Goutaland, 2003, Kovacs & Faria, 2004, Solomon, 1999, Stone & Grönhaug, 1993),

mainly because choice is often associated with uncertainty (J. W. Taylor, 1974) and

possibility of loss (Bauer, 1960). Specifically, it is an important concept in service marketing, due to the fact that a service is intangible, variable and its production is inseparable from its consumption (Lewis & Chanmers, 2000, Zeithaml, Parasuraman & Berry, 1985). Thus, it is impossible to guarantee what the final outcome of a service will be, which makes its purchase a risky decision. Consumers perceive risk when a purchase is expensive, complex or difficult to understand (Solomon, 1999).

There are three reasons that underlie the importance of understanding consumer perceived risk (Mitchell, 1999). The first of them is that perceived risk theory has an intuitive appeal and is important in facilitating marketers seeing the world through their customers‘ point of view. The second reason is that it can be applied to a number of marketing

applications. Finally, perceived risk seems to be more influential at explaining consumer‘s behaviors as consumers usually are more concerned about avoiding mistakes than about maximizing utility in their decisions.

Recently, the literature suggested that hope can be one factor which influences risk perception (A. R. D. Almeida, 2010, Averil et al., 1990, Lazarus, 1999, Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005, Snyder 2002). First, it is important to contextualize risk in hoped for situations: every uncertain situation involves a certain degree of risk, because there is always the risk of not achieving the desired outcome. Because hope only exists for uncertain situations, it is always related to risk. However, hope seems to lead people to run the involved risk (Averill et al., 1990, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005), while fear would prevent them to do so (Bovens, 1999). People may decide to run the risk because they do not perceive it as too high, if compared to not hoped-for situations.

For example, Cooper, Woo, and Dunkelberger (1988) found that entrepreneurs tend to have an overly optimistic perception of the risks involved. One reason behind this decrease in the perceived risk may be high levels of hope to succeed in their new ventures. Another example is Hopfensitz (2006)‘s study, which found that hope predicted risk preferences in investment decisions.

beneficial ones, unlike most every day situations in which risk and benefits are positive correlated. The explanation for it is that this perception is affected by affective evaluations (Alhakami & Slovic, 1994). Again, these subjects‘ hope to get the benefits may be lowering the risk perception of the high beneficial situations.

Hope can be reflected in risk taking behaviors in all domains: economic, social, psychological and physical (MacInnis & Chun, 2007). For this reason, it is reasonable to understand that these risky behaviors may be related to a distortion in perceived risk.

The first reason supporting this relation between hope and risk perception was pointed by MacInnis and de Mello (2005). They explained that when searching for congruent

information, people may ignore information pointing to the likelihood of negative

consequences. So, high levels of hope may lower the perception of risks that a purchase or consumption process might involve.

This process has been found to happen for positive emotions in general, which reduce risk perception if compared to negative emotions (Chaudhuri, 2002). For instance, people believe a medical treatment to be riskier when their emotions are negative rather than positive (Bowen et al., 2003). If hope could be considered a positive emotion (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1994, Lazarus, 1999, MacInnis & Chun, 2007, MacInnis & de Mello, 2005) or could evoke them (Snyder, 2000), it would seem reasonable to infer that higher levels of hope lead to reduced risk perception.

The second reason is that defence mechanisms lead people to only pay attention to non-risky decisions aspects (MacInnis & de Mello, 2005). For example, a person who hopes to lose weight may ignore the side effects information displayed on a medicine label.

Third, because people tend to rely more on information which is congruent to their initial beliefs (Nisbett & Ross, 1980), they are more likely to terminate the process of searching for information earlier when the information found supports a desired conclusion than when it does not (Edwards & Smith, 1996). Thus, people high in hope may look for less information to avoid finding incongruent information. As a consequence, these people are led to believe that there is no incongruent information to be found.

Fourth, if risk information is processed, one is likely to counter-argument this

Fifth, hope brings to mind favorable images (MacInnis & Price, 1987), which can reduce the perception of consequences‘ severity. Thus, because of negative images being less latent, they seem less likely to happen, due to the fact that people tend to place too much weight on highly salient data (Kruglanski, 1989).

Finally, A. R. D. Almeida (2010) linked hope to perceived risk in her model, suggesting that hope is an antecedent of risk perception. The author empirically tested this relation in the context of plastic surgery, indicating that women who strongly hope to look more attractive perceive plastic surgery as less risky than women whose hope is weaker.

A summary of the reasons why hope should reduce risk perception is displayed in Table 4.

Table 4

Why Hope Should Reduce Consumers’ Risk Perception

Reason Source

When searching for congruent information, people may ignore information pointing to the likelihood of negative consequences.

MacInnis & de Mello (2005).

Positive emotions in general reduce risk perception if compared to negative emotions.

Chaudhuri (2002).

Defence mechanisms lead people to only pay attention to non-risky decisions aspects.

MacInnis & de Mello (2005).

People tend to terminate the process of searching for information earlier when the information found supports a desired conclusion than when it does not.

Edwards & Smith (1996).

If risk information is processed, one is likely to counter-argument this information or to change her/his own acceptance criteria.

MacInnis & de Mello (2005).

Hope brings to mind favorable images, which can reduce the perception of

consequences‘ severity. MacInnis & Price (1987). Because of negative images being less latent, they seem less likely to happen,

due to the fact that people tend to place too much weight on highly salient data.

Kruglanski (1989).

Source: developed by the author

From all domains cited before, the focus of this thesis will be on the perception of financial risk. There is financial risk when there is some monetary cost and the possibility of losing goods and money on this transaction (Solomon, 1999), monetary loss because of product‘s malfunction, cost of repair, cost of opportunity and functionality loss (A. R. D. Almeida, 2010, Hawkins, Mothersbaugh & Best, 2007).