Universidade de Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro

ENHANCING BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF THE OLIVE MOTH,

PRAYS OLEAE (BERNARD) (LEPIDOPTERA: PRAYDIDAE) IN

ORGANIC OLIVE GROVES BY INCREASING FUNCTIONAL

BIODIVERSITY

Tese de Doutoramento em Ciências Agronómicas e Florestais

Anabela Cristina Marques da Nave Rodrigues

Orientadora: Professora Doutora Laura Monteiro Torres

Coorientadora: Doutora Mercedes Campos Aranda

Trabalho realizado no âmbito da Bolsa de Doutoramento SFRH/BD/34394/2008 pela Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT), financiada pelo Programa Operacional Potencial Humano (POPH) – Quadro de Referência Estratégico Nacional (QREN) – Tipologia 4.1 Formação Avançada,comparticipado pelo Fundo Social Europeu (FSE) e por Fundos Nacionais do Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Ensino Superior.

Os trabalhos realizados no âmbito desta tese de Doutoramento são parte integrante do projecto “Incremento da biodiversidade funcional do olival, no fomento da protecção biológica contra pragas da cultura” (Refª PTDC/AGR-AAM/100979/2008), tendo sido financiado por fundos FEDER através do Programa Operacional Factores de Competitividade COMPETE (Refª FCOMP-01-0124-FEDER-008685) e por Fundos Nacionais através da Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT).

vii Agradecimentos

Ao professor Pedro Amaro, do Instituto Superior de Agronomia, ISA, que na minha licenciatura na Universidade de Évora me sensibilizou para a importância da Protecção Integrada e me apoiou e acompanhou até ao Doutoramento. Foi o principal motor.

À minha orientadora Doutora Laura Torres, do Departamento de Protecção das Plantas, UTAD, que acreditou que também EU podia contribuir para o que considera os desafios de uma agricultura sustentável, minha mentora na investigação. O seu contributo muito ultrapassa o papel de um orientador. Trabalho de campo, de laboratório, convívio, partilhas, estadia por Vila Real. É difícil expressar em palavras o reconhecimento.

À minha coorientadora Doutora Mercedes Campos, da Estacão Experimental de Zaidín, Conselho Superior de Investigação Científica de Espanha, por todo o apoio e incentivo desde a fase inicial, condições que me permitiu no estágio em Granada, até este final.

À Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, pelos apoios concedidos.

À Associação de Agricultores para Produção Integrada de Frutos de Montanha, AAPIM; direcção, assessoria e técnicos, que me acolheram como se fizesse parte da equipa; cedência do laboratório, materiais, idas ao campo, acesso a olivais e confraternização.

À equipa da Estação Experimental de Zaidín, sob a coordenação da Doutora Mercedes, que me recebeu para a fase inicial do trabalho com crisopas; Mário, Belen, Luísa, Hermínia, Daniel. Fui muito bem acolhida, aprendi muito e guardo saudades da estadia por Granada.

À equipa do projecto “Incremento da biodiversidade funcional do olival, no fomento da protecção biológica contra pragas da cultura”, pela partilha de conhecimentos e momentos vividos nas várias reuniões e em particular ao Bartolomeu e à Darinka, bolseiros no projecto, pela seriedade do vosso trabalho e boa execução das tarefas que ficaram a vosso cargo.

Ao Dr. Mark Jervis e Dr. Carsten Muller, Universidade de Cardiff, Reino Unido e ao Dr. Howard Thistlewood, Pacific Agri-Food Research Centre, Canada, pelo apoio na investigação. À Doutora Ana Nazaré Pereira, da UTAD, pela cedência dos recursos do laboratório de Fitopatologia, equipa e material, e pela sua matinal simpatia.

Ao Carlos e à Ana do laboratório de Fitopatologia, da UTAD. A vossa sempre boa receptividade e apoio em muitas fases deste trabalho foi crucial.

Ao Doutor António Crespi, da UTAD, que me orientou para a inventariação da flora dos olivais e me ajudou na identificação. O que aprendi de plantas e o que todos estes trabalhos encheram de cor a minha vida e os laboratórios por onde passei!

viii

Ao Doutor Fernando Nunes, da UTAD, pela vertente química desta tese. Por conseguir sempre tempo para os “meus bichos e plantas” e desafios que fomos acrescentando. Todo o apoio da sua prestável equipa de bolseiros e disponibilidade sempre de um espaço nos laboratórios de química, permitiram irmos progredindo em tarefas que se tornaram indispensáveis para esta tese.

À Doutora Rita Teixeira, do Instituto Nacional de Investigação Agrária e Veterinária, pela identificação dos parasitoides e por ter permitido que colaborasse na identificação.

À Conceição Rodrigues, pelo apoio nas muitas tarefas e pela partilha de muitos dos bons momentos vividos por Vila Real. A atitude, alegria e amizade fizeram parte dos momentos positivos deste doutoramento. “Ó menina!”

À Catarina Lourenço. Partilhámos na AAPIM idas ao campo, trabalhos de laboratório também aos fins-de-semana, pensamentos, saberes, sabores e viveres.

Às minhas amigas do norte. À Fátima Gonçalves e à Cristina Carlos. A Fátima pelo seu exemplar profissionalismo e colaboração em TODAS as fases; campo, laboratório aos fins-de-semana, feriados e trabalho noites dentro. Porque os insectos em laboratório não param ao fim-de-semana e a Fátima foi muitas vezes sozinha esse “staff”. À Cristina com o seu sorriso e riso, por partilhar a investigação da vinha com a que fazíamos no olival. “Olhai!” O que vivemos por causa dos nossos doutoramentos. As horas no laboratório são difíceis de contabilizar como são também todas as restantes de tão boa confraternização; patuscadas, caminhadas, música, animais. Fazer parte desta equipa permitiu fazer este percurso com enorme prazer. Nas nossas diferenças construímos pontes para aprendizagem, partilha e amizade que mantemos.

Aos coautores dos trabalhos produzidos, porque somos pequenos enquanto individuais e grandes em bons grupos e boas parcerias.

À minha família, em particular ao Joaquim e à Eva por terem permitido tanta ausência e apoiado em momentos tão decisivos. A minha tese fez parte dos afazeres da família; fomos para trabalho de campo, para Granada, para eventos. As plantas e os insectos partilharam também a nossa casa.

Termino esta tese com 50 anos. Um percurso profissional e de vida. Um marco na minha existência e motivo de satisfação para mim e todos os que comigo viveram este caminho; me ajudaram, me desafiaram, me fizeram ver, pensar, viver, sentir, rir, partilhar dúvidas e descobertas, me ajudaram a crescer enquanto ser humano e me permitiram ter um desempenho positivo para o planeta e para a Ciência.

xi

Resumo

O presente estudo pretende aprofundar o conhecimento sobre as possibilidades oferecidas pelo fomento da biodiversidade do olival no incremento da protecção biológica de conservação contra a traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae (Bernard), considerada praga-chave da cultura em análise. Nesse sentido, procurou identificar-se um conjunto de espécies de plantas espontâneas do ecossistema olival, no centro e norte interior de Portugal, capaz de facultar, aos principais inimigos naturais de P. oleae, os recursos alimentares (e.g. pólen, néctar) essenciais ao seu bom desempenho, sem contudo beneficiarem a praga. Incidiu-se sobre espécies de inimigos naturais, reconhecidas como importantes na regulação das populações da praga em condições de não manipulação do habitat, i.e. o predador, Chrysoperla carnea e os parasitóides Chelonus

elaeaphilus, Apanteles xanthostigma, Ageniaspis fuscicollis e Elasmus flabellatus. No

desenvolvimento do estudo, que decorreu entre 2008 e 2012, adoptaram-se os princípios da Engenharia Ecológica, pelo que o mesmo se estruturou nas seguintes fases: a) identificação de plantas produtoras de flor espontâneas no olival, potencialmente interessantes enquanto fonte de alimento para inimigos naturais de P. oleae; para isso, efetuaram-se inventários florísticos em 39 olivais situados em diferentes regiões da Beira Interior e selecionaram-se 21 espécies para avaliação: Conopodium majus, Daucus carota, Foeniculum vulgare, Asparagus

acutifolius, Andryala integrifolia, Chondrilla juncea, Dittrichia viscosa, Sonchus asper, Echium plantagineum, Capsella bursa-pastoris, Raphanus raphanistrum, Lonicera hispanica, Silene gallica, Spergula arvensis, Trifolium repens, Hypericum perforatum, Calamintha baetica, Lavandula stoechas, Malva neglecta, Anarrhinum bellidifolium e Linaria saxatilis; b)

obtenção de exemplares de P. oleae e dos parasitóides a estudar; para isso, colheu-se em olivais de Trás-os-Montes e Beira Interior, nas três gerações da praga (filófaga, antófaga e carpófaga), material vegetal atacado (folhas, cachos florais e frutos, respectivamente), contendo lagartas e pupas. Este estudo permitiu atualizar o conhecimento sobre o complexo de parasitóides de P.

oleae em Portugal; obtiveram-se 23 taxa, que diferiram entre as gerações do fitófago e entre

anos e que incluíram as espécies: Diadegma armillata, Scambus elegans, A. xanthostigma,

Bracon crassicornis, C. elaeaphilus, E. flabellatus, Pnigalio agraules e A. fuscicollis. Outros

taxa, estes referidos pela primeira vez como fazendo parte do complexo parasitário de P. oleae em Portugal foram: Brachymeria sp., Haltichella sp., Hockeria sp., Chrysocharis sp.,

Tetrastichus sp. e Euderus albitarsis, bem como membros das subfamílias, Brachymeriinae,

xii

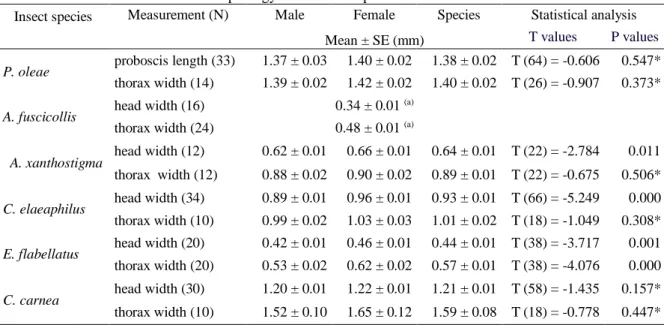

Pteromalidae; c) avaliação da possibilidade teórica de acesso de P. oleae e de cinco dos seus principais inimigos (i.e. os parasitóides A. xanthostigma, C. elaeaphilus, E. flabellatus e A.

fuscicollis e o predador C. carnea) ao néctar das espécies da flora selecionadas; para o efeito

analisou-se a arquitectura das flores, bem como a estrutura da armadura bucal e / ou a largura da cabeça e tórax da praga e dos seus inimigos, com recurso ao programa informático Digital Imaging Solutions (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH, Olympus Europa). Os resultados mostram que os auxiliares em estudo são capazes de alcançar o néctar da maior parte das espécies de plantas testadas e que P. oleae não é capaz de aceder ao néctar de cinco dessas espécies, nomeadamente A. integrifolia, C. juncea, D. viscosa, S. asper e L. stoechas; d) avaliação do efeito de diferentes açúcares que ocorrem na natureza (i.e. galactose, manose, trealose, melibiose, rafinose, melezitose, frutose, sacarose, glicose e maltose), bem como de flores de diferentes espécies de plantas anteriormente selecionadas, em parâmetros chave da biologia de P. oleae e dos seus inimigos em estudo nomeadamente, longevidade, período de pré-postura e de postura, e fecundidade); os quatro últimos açúcares testaram-se em relação a

P. oleae e a C. elaeaphilus, e a sua totalidade testou-se relativamente a C. carnea. Verificou-se

que a trealose, maltose, melibiose, glicose e frutose, beneficiaram C. carnea; por outro lado a sacarose e glicose tiveram efeito positivo na biologia de C. elaeaphilus, e a glicose, frutose, maltose e sacarose beneficiaram P. oleae. Também se verificou que as flores de C. majus, F. vulgare L. hispanica e A. acutifolius tiveram impacto positivo na fecundidade e longevidade de C. carnea, admitindo-se que para isso tenha contribuído o teor em trealose do seu pólen e/ou

néctar. No caso de P. oleae a longevidade foi incrementada com o acesso a A. integrifolia, E. plantagineum, H. perforatum, M. neglecta e L. stoechas.

Os resultados indicam que a flora residente no olival apresenta potencial para ser usada como infraestrutura ecológica no incremento da protecção biológica de conservação contra P.

oleae.

Palavras-chave: interacções tróficas, plantas espontâneas, olivicultura sustentável, protecção

xiii

Abstract

This study aims at broadening the knowledge about the role of the olive grove agroecosystem biodiversity in conservation biological control increment against the olive moth,

Prays oleae (Bernard), which is considered a key pest of the olive crop. We sought to identify

a group of spontaneous plants’ species in the olive grove ecosystem, from the center and interior north of Portugal, adequate to provide to the main P. oleae natural enemies essential food resources (e.g. pollen, nectar) crucial to their good performance and without benefiting the pest. The work focused on natural enemies´ species recognized as important in the control of the pest populations in unmanipulated habitat, i.e. the predator Chrysoperla carnea and the parasitoids

Chelonus elaeaphilus, Apanteles xanthostigma, Ageniaspis fuscicollis and Elasmus flabellatus.

The study took place between 2008 and 2012 in accordance with the principles of Ecological Engineering, thus being structured in the following stages: a) identification of spontaneous flowering plants from the olive grove agroecosystems potentially interesting as natural food sources to the P. oleae natural enemies; therefore, floristic surveys were made in 39 olive groves in different regions of Beira Interior and 21 species were selected: Conopodium majus, Daucus

carota, Foeniculum vulgare, Asparagus acutifolius, Andryala integrifolia, Chondrilla juncea, Dittrichia viscosa, Sonchus asper, Echium plantagineum, Capsella bursa-pastoris, Raphanus raphanistrum, Lonicera hispanica, Silene gallica, Spergula arvensis, Trifolium repens, Hypericum perforatum, Calamintha baetica, Lavandula stoechas, Malva neglecta, Anarrhinum bellidifolium and Linaria saxatilis; b) collection of P. oleae and parasitoids individuals for the

experiments; hence, olive tree leaves, floral branches and fruits containing larvae and pupae of the phytophagous were collected in olive groves located in Trás-os-Montes and Beira Interior regions during its three generations (phyllophagous, anthophagous and carpophagous, respectively). This allowed to update the knowledge about P. oleae parasitoids’ complex in Portugal; 23 taxa were obtained, which differed among P. oleae generations and studied years,

i.e. Diadegma armillata, Scambus elegans, A. xanthostigma, Bracon crassicornis, C. elaeaphilus, E. flabellatus, Pnigalio agraules and A. fuscicollis; other taxa, recognized for the

first time in Portugal as P. oleae parasitoids comprise: Brachymeria sp., Haltichella sp.,

Hockeria sp., Chrysocharis sp., Tetrastichus sp. and Euderus albitarsis, and members of the

subfamilies Brachymeriinae, Haltichellinae, Euderinae, Entedontinae, Meteorinae and Opiinae and the families Mymaridae and Pteromalidae; c) analysis of the theoretical nectar accessibility of the selected flora by P. oleae and five of its main natural enemies (i.e. the parasitoids A.

xiv

xanthostigma, C. elaeaphilus, E. flabellatus and A. fuscicollis and the predator C. carnea); thus

the flowers’ architecture and the structure of the mouthparts and / or the width of the head and the thorax of the pest and its enemies were studied using the computer program Digital Imaging Solutions (Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH, Olympus Europe). The results show that the entomophagous can reach the nectar of most plants’ species investigated whilst P. oleae is not able to access the nectar of five of them, namely A. integrifolia, C. juncea, D. viscosa, S.

asper and L. stoechas; d) analysis of the role of different sugars naturally occurring (i.e.

galactose, mannose, trehalose, melibiose, raffinose, melezitose, fructose, glucose, sucrose, and maltose) and of different flower’s species identified in key parameters of P. oleae biology and in its natural enemies under study (i.e. longevity, pre-oviposition and oviposition periods, and fecundity); all the sugars were tested regarding C. carnea and the last aforementioned four were studied in relation to P. oleae and C. elaeaphilus. It was found that trehalose, maltose, melibiose, glucose and fructose benefit C. carnea; sucrose and glucose had a positive impact in the biology of C. elaeaphilus, and glucose, fructose, maltose and sucrose benefited P. oleae biology. It was also found that the flowers of C. majus, F. vulgare L. hispanica and A. acutifolius increased the fecundity and the longevity of C. carnea, admittedly in relation to the

trehalose content of their pollen and/or nectar. The longevity of P. oleae was enhanced with access to A. integrifolia, E. plantagineum, H. perforatum, M. neglecta and L. stoechas.

As a whole, our results indicate that the resident flora of the olive grove agroecosystem have an important potential to be used as ecological infrastructure in the increment of conservation biological control against P. oleae.

Keywords: trophic interactions, spontaneous plants, sustainable olive, conservation biological

xv

Scientific publications

International peer-reviewed papers

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F.M., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Evaluating potential sugar food sources from the olive grove agroecosystems for Prays oleae parasitoid Chelonus

elaeaphilus. Biocontrol Science & Technology (submitted).

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Is there incompatibility between wild vegetation in the olive grove agroecosystems and conservation biological control of Prays oleae? Journal of Pest Science (submitted).

Nave, A., Crespí, A.L., Gonçalves, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources for natural enemies of insect pests. Ecological Research Journal (accepted).

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Teixeira, R., Costa, C.A., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Parasitoid complex of Prays oleae (Lepidoptera: Praydidae). Turkish Journal of Zoology (accepted).

Gonzalez, D., Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F.M., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Higher longevity and fecundity of Chrysoperla carnea, a predator of olive pests, on some native flowering mediterranean plants. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 36 (2): 1-10. (IF4.141; Q1; times cited: 1).

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Crespí, A.L., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Evaluation of native plant flower characteristics for conservation biological control of Prays oleae. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 106 (2): 249-257. (IF1.761; Q1; times cited: 1).

Gonzalez, D., Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Effects of ten naturally occurring sugars on the reproductive success of the green lacewing, Chrysoperla carnea. BioControl, 61 (1): 57-67. (IF1.767; Q1; times cited: 3).

National peer-reviewed papers

Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M.C., Nave, A., Falco, V., Arnaldo, P., Torres, L. 2012. Avaliação de plantas espontâneas do olival para fomento da protecção biológica de conservação. Revista de Ciências Agrárias, 35 (2): 250-254.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2012. Poderá o desempenho de Chelonus elaeaphilus beneficiar do acesso a fontes de açúcar? Revista de Ciências Agrárias, 35 (2): 244-249.

xvi

Poster presentations in international conferences

Adán, A., Bento, A., Budia, F., Campos, M., Cotés, B., González, M., Jerez, C., Paredes, D., Nave, A., Medina, P., Pascual, F., Pascual, S., Pereira, J., Porcel, M., Rei, F., Ros, P., Ruano, F., Ruíz, M., Sánchez, I., Santos, S., Seris, E., Torres, L., Viñela, E. 2010. RIESPO: Iberian network on the evaluation of efficacy and side effects of control treatments against olive pests. 8th International

Symposium on Fruit Flies of Economic Importance", September, Valencia, Spain.

Nave, A., Crespí, A., Campos, M., Torres, LM. 2009.Infestantes do olival com interesse potencial na limitação natural da traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae. XII Congresso da Sociedad Española de Malherbologia (SEMh) /XIX Congresso da Asociacion Latinoamericana de Malezas (ALAM)/ II Congresso Iberico de Ciencias de las Malezas(IBMC), 10-13 Novembro, Lisboa, Portugal. Vol 1: 39-42;ISBN: 978-972-8669-44-7.

Oral presentations in international conferences

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M.C., Nunes, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2012. Preliminary evaluation of sugars from flowering plants as food resources for Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae) in an olive agroecosystem. 5th IOBC/wprs Working Group “Landscape Management for Functional Biodiversity”, 7-10 May, Lleida, Spain. Bull OILB/SROP 75: 137-141; ISBN: 978-92-9067-252-4.

Nave, A., Porcel, M., Cotes, B., Fernandez, M.L., Barroso, H., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2011. Suitability of four naturally occurring sugars for adult Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae). VII Congreso Nacional de Entomología Aplicada y XII Jornadas de la SEEA, 24-28 October, Baeza, Spain.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2011. Does the occurrence of Saissetia oleae at the olive grove have a key role in the population dynamics of Chrysoperla carnea? XI International Symposium on Neuropterology, 16-22 June, Ponta Delgada, Açores, Portugal.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Crespí, A.L., Rei, F., Campos, M., Torres, L.M. 2011. Assessing the theoretical néctar accessibility on flowering weeds from the olive grove for the olive moth and three natural enemies. 5th IOBC/wprs Working Group-Integrated Protection of Olive Crops, 15-20 May, Jerusalém, Israel.

xvii

Poster presentations in national conferences

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Nunes, F., Campos, M., Torres, L.2011. Poderá o desempenho de Chelonus elaeaphilus beneficiar do acesso a fontes de açúcar? 9º Encontro Nacional de Protecção Integrada, 17-18 Novembro 2011, Escola Superior Agrária de Viseu, Viseu, Portugal. 70 ISBN: 978-989-97584-0-7.

Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M.C., Nave, A., Falco, V., Arnaldo, P., Torres,L. 2011. Avaliação de plantas espontâneas do olival para fomento da protecção biológica de conservação. 9º Encontro Nacional de Protecção Integrada, 17-18 Novembro 2011, Escola Superior Agrária de Viseu, Viseu, Portugal. 71 ISBN: 978-989-97584-0-7.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M.C., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2011. A gestão da flora espontânea do olival na conservação dos antagonistas da traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae (Bernard). Conferência Gestão e Conservação de Habitats e Flora Associada, 25 Março, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, Portugal.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M.C., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2010. Incremento da actuação da crisopa-comum, Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens), no olival em agricultura biológica. 3º Congresso Nacional de Agricultura Biológica, 18-19 Novembro, Braga, Portugal.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2010. O fomento da biodiversidade do olival no incremento da protecção biológica contra a traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae (Bernard). 12º Encontro Nacional de Ecologia, 18-20 Outubro, Porto, Portugal.

Oral presentations in national conferences

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2012. Poderão os adultos de traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae (Bernard) beneficiar do acesso a fontes de hidratos de carbono? VI Simpósio Nacional de Olivicultura. Mirandela. 15 a 17 de Novembro. Actas Portuguesas de Horticultura, 21: 229- 236; ISBN: 978-972-8936-12-9.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Rodrigues, M., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2011. Qual o papel do funcho-bravo, Foeniculum vulgare Miller na protecção biológica de conservação contra pragas do olival? 3º Colóquio Nacional de Horticultura Biológica/ 1º Colóquio Nacional de Produção Animal Biológica. Braga, 22 a 23 de Setembro 2011, p. 97.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F. 2011. Protecção biológica de conservação contra pragas: um estudo de caso. 2as Jornadas Nacionais de Olivicultura Biológica. “Olival: bens e serviços do ecossistema”. Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo, 9 e 10 de Setembro.

Nave, A., Crespí, A., Campos, M., Torres, L.M. 2009. A gestão do olival no fomento da limitação natural das populações de traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae (Bernard) – resultados preliminares relativos à

xviii

Beira Interior. V Simpósio Nacional de Olivicultura, Escola Superior Agrária de Santarém, 25 e 26 de Setembro.

Technical disclosure documents

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Torres, L. 2011. As crisopas. Auxiliares valiosos do olivicultor. Projecto Incremento da biodiversidade funcional do olival, no fomento da protecção biológica contra pragas da cultura. Refª PTDC/AGR-AAM/100979/2008.Vila Real, 4 pp.

Gonçalves, F., Nave, A., Torres, L. 2011. As apiáceas. Um tesouro de biodiversidade. Projecto Incremento da biodiversidade funcional do olival, no fomento da protecção biológica contra pragas da cultura. Refª PTDC/AGR-AAM/100979/2008.Vila Real, 4 pp.

Publications in national journals

Gonçalves, F., Nave, A., Torres, L. 2011. Os crisopídeos, sua importância no olival – medidas de valorização da sua actividade. O Segredo da Terra, 33: 38-40.

Nave, A., Gonçalves, F., Torres, L. 2011. Protecção biológica de conservação contra a traça-da-oliveira. Revista Frutas Legumes e Flores, 121: 30-33.

Torres, L., Nave, A., Gonçalves, F. 2008. Biodiversidade funcional na protecção contra pragas. Revista Frutas Legumes e Flores, 102: 25-26.

International cooperation

In the course of this thesis, international contacts were made and the help and cooperation of the following institutions and individuals were obtained:

1 Cardiff University, United Kingdom

- Mark A Jervis, Biosciences Department Professor 2 Cardiff University, United Kingdom

xix Table of contents

Resumo ... xi

Abstract... xiii

Scientific publications ... xv

International cooperation ...xviii

Table of contents ... xix

List of figures ...xxiii

List of tables ... xxv Chapter 1 General Introduction ... 27 1.1 General Introduction ... 29 1.2 References ... 33 Chapter 2 Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources for natural enemies of insect pests ... 37

Abstract... 39

Resumo ... 41

2.1 Introduction ... 43

2.2 Material and methods ... 45

2.3 Results ... 46

2.4 Discussion ... 51

2.5 References ………...……… 54

Chapter 3 Parasitoid complex of Prays oleae (Lepidoptera: Praydidae) ... 61

Abstract... 63

Resumo ... 65

3.1 Introduction ... 67

3.2 Materials and methods ... 68

3.3 Results ... 69

3.4 Discussion ... 77

3.5 References ... 78

Chapter 4 Evaluation of native plant flower characteristics for conservation biological control of Prays oleae ... 83

Abstract... 85

Resumo ... 87

4.1 Introduction ... 89

4.2 Material and methods ... 91

4.2.1 Insects ... 91

4.2.2 Plant species ... 92

xx 4.2.4 Flower morphology ... 94 4.2.5 Data analysis ... 95 4.3 Results ... 95 4.3.1 Measurements of insects ... 95 4.3.2 Measurements of flowers ... 95

4.3.3 Theoretical nectar accessibility ... 97

4.4 Discussion ... 98

4.5 References ... 100

Chapter 5 Effects of ten naturally occurring sugars on the reproductive success of the green lacewing, Chrysoperla carnea ... 105

Abstract... 107

Resumo ... 109

5.1 Introduction ... 111

5.2 Material and methods ... 112

5.2.1 Experimental insects ... 112

5.2.2 Sugar diet treatments ... 112

5.2.3 Development, fecundity and life table parameters ... 112

5.2.4 Data analysis ... 112

5.3 Results ... 113

5.4 Discussion ... 117

5.5 References ... 118

Chapter 6 Longevity and fecundity of C. carnea, a predator of olive pests, on some native flowering Mediterranean plants ... 125

Abstract... 127

Resumo ... 129

6.1 Introduction ... 131

6.2 Material and methods ... 133

6.2.1 Plant selection criteria ... 133

6.2.2 Chrysoperla carnea rearing ... 133

6.2.3 Effect of different flowers on the longevity and fecundity of C. carnea adults ... 133

6.2.4 Pollen and nectar sugar collection ... 135

6.2.5 Pollen and nectar preparation for sugar analysis... 135

6.2.6 Quantification of nectar and pollen sugar content ... 135

6.2.7 Statistical analysis ... 136

6.3 Results and Discussion ... 136

6.3.1 Effect of different flowers on C. carnea biological parameters ... 136

6.3.2 Nectar and pollen floral sugar composition and content ... 138

6.3.3 Effect of nectar and pollen floral sugar content on C. carnea reproduction and longevity ... 140

xxi

6.4 Conclusion ... 143

6.5 References ... 145

Chapter 7 Evaluating potential sugar food sources from the olive grove agroecosystems for Prays oleae parasitoid Chelonus elaeaphilus ... 149

Abstract... 151

Resumo ... 153

7.1 Introduction ... 155

7.2 Material and methods ... 156

7.2.1 Insects ... 156

7.2.2 Survival experiments ... 156

7.2.3 Flower nectar composition and content ... 157

7.2.4 Data analysis ... 157

7.3 Results ... 158

7.3.1 Survival experiments ... 158

7.3.2 Floral nectar sugar composition and content ………160

7.4 Conclusion ... 161

7.5 References ... 162

Chapter 8 Is there incompatibility between wild vegetation in the olive grove agroecosystem and conservation biological control of Prays oleae? ... 165

Abstract... 167

Resumo ... 169

8.1 Introduction ... 171

8.2 Material and methods ... 172

8.2.1 Plant species treatments ... 172

8.2.2 Sugars diet treatments ... 173

8.2.3 Insects ... 173

8.2.4 Effect of flowering plants on the biological parameters of P. oleae ... 173

8.2.5 Effect of sugars on the biological parameters of P. oleae ... 174

8.2.6 Data analysis ... 174

8.3 Results ... 175

8.3.1 Experiments with flowers ... 175

8.3.2 Experiments with sugars ... 178

8.4 Discussion ... 180 8.5 References ... 183 Chapter 9 Conclusion ... 187 9.1 Main Results ... 189 9.2 Future perspectives ... 192 9.3 Final remarks... 193

xxiii

List of figures

Chapter2

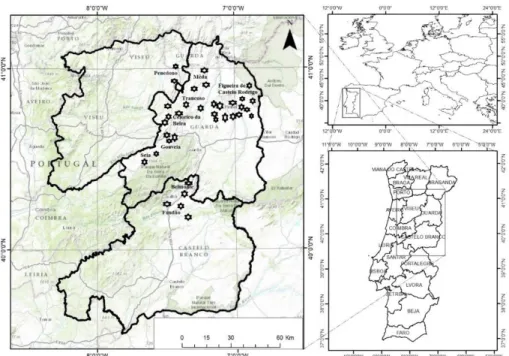

Figure 2.1 Map of study area showing the distribution of the groves where floristic surveys were done……….……. 46 Figure 2.2 Distribution (%) of the flowering plant species identified in the olive groves

by a) the most representative families and b) by physiognomic types…………... 49 Figure 2.3 Trophic interactions in olive grove agroecosystems………. 54 Chapter3

Figure 3.1 Distribution of the parasitoids collected by superfamily and family..…….. 70 Figure 3.2 Some of the parasitoids of P. oleae collected in this study, not yet identified

in Portugal………... 71 Figure 3.3 Canonical correspondence analysis between parasitoids and pest

generations. ……… 77 Chapter4

Figure 4.1 Measurements of Prays oleae and its studied natural enemies morphological parameters. ………. 94 Figure 4.2 Measurements of the flower morphology, shown for the case of Raphanus

raphanistrum. ……….. 95

Chapter5

Figure 5.1 Survival rate (solid line) and lifetime fecundity (dashed line) of C. carnea adults reared on different diets……… 116 Chapter6

Figure 6.1 a) Chrysoperla carnea adult feeding on Foeniculum vulgare flowers; both the nectar and pollen of these flowers have trehalose, a nutrient found to enhance predator’s performance, b) example of the climate chamber experiment aimed at evaluating the effect of 11 native Mediterranean plant species on the longevity and fecundity of C. carnea adults. Plants were randomly distributed on the benches within the climate chamber………... 134 Figure 6.2 a Nectar scatter plot obtained by representing PC1 vs. PC2. b Pollen score

plot obtained by representing PC1 vs. PC2. MSs monosaccharides, Treh. trehalose, Gal. galactose, Glu. glucose, Fru. fructose, Suc. sucrose, Meleb. melebiose, Melez. melezitose, Oss oligosaccharides, Fecund. female C. carnea fecundity, Long M C. carnea male longevity, Long. F. C. carnea female longevity ……… 141 Figure 6.3 a Projection of nectar flower species samples according to their sugar

content in PC1 and PC2 sample scores. b Projection of pollen flower species samples according to their sugar content in PC1 and PC2 sample scores……….. 142 Chapter7

Figure 7.1 Kaplan–Meier estimates of the survival functions for Chelonus elaeaphilus (a) females (n = 4 to 13) and (b) males (n = 6 to 10) reared on the sugar diets tested. Different letters indicate significant differences among treatments after pairwise comparison of the survival curves……… 158 Figure 7.2 Kaplan–Meier estimates of the survival functions for males and females of

xxiv

Figure 7.3 Examples of chromatogram obtained by HPAEC-PAD for the nectar of the studied plants: A) Echium plantagineum B) Lavandula stoechas C) Conopodium

xxv List of tables

Chapter2

Table 2.1 Flowering plant species from the ground cover of the studied olive groves (October /November of 2008). ... 47 Table 2.2 Biodiversity indexes of ground cover from the studied olive groves. ... 50 Table 2.3 Plant species identified in the present study, flowering period and references about

families of entomophagous insects visiting them. ... 53 Chapter3

Table 3.1 Percentage of larvae and pupae of P. oleae from which have emerged parasitoids in each generation and year of study. In parentheses the total number of individuals observed……….…. 69 Table 3.2 Parasitoids of larvae and pupae of P. oleae collected in all groves and studied years

by taxa, total number of individuals and percentage (%) from the total. ... 71 Table 3.3 Percentage (%) of larvae and pupae of P. oleae parasitized by each of the identified

species of parasitoids in each year and generation. ... 72 Table 3.4 Climatic characterization of the four years under study; temperature (Temp.) and

precipitation (Precipit.). ... 73 Chapter4

Table 4.1 Plant species selected in this study, corresponding criteria and flowering period. .. 93 Table 4.2 Measurements of insect morphology of the insect species studied. ... 96 Table 4.3 Flower species used and floral architecture measurements. ... 96 Table 4.4 Theoretical accessibility to floral nectar of the plant species studied by the insect

species. ... 97 Chapter5

Table 5.1 Average male and female longevity, pre-oviposition period, oviposition period, lifetime fecundity and daily fecundity (mean ± SE) of C. carnea fed with different diets in the adult stage. ... 114 Table 5.2 Mean (±SE) net reproductive rate (Ro), generation time (Gt), intrinsic rate of

natural increase (rm), finite capacity for increase (k), and population doubling time (Dt) of C. carnea fed with different diets in the adult stage and E. kuehniella eggs in the larval stage... 117 Chapter6

Table 6.1 Average male and female longevity, pre-oviposition period, oviposition period, and fecundity (mean ± SE) of C. carnea fed with different flowering plant species. ... 137 Table 6.2 Sugars composition and content (mean ± SE) of the flowering nectar and pollen

Mediterranean plants. ... 139 Chapter7

Table 7.1 Architecture characterization of flowers of the plant species. ... 158 Table 7.2 Lifespan (days) (mean ± SE) and 95% confidence interval of male adults of

Chelonus elaeaphilus fed on different sugar diets.. ... 158

Table 7.3 Sugar ratio classification of the studied wild flowering plant species from the olive grove agroecosystem……….160 Chapter8

xxvi

Table 8.1 Average (mean ± SE) of male and female longevity, pre-oviposition and oviposition periods and lifetime fecundity of P. oleae provided with different flowering plant species or with water only, in the phyllophagous generation. ... 176 Table 8.2 Average (mean ± SE) of male and female longevity, pre-oviposition and

oviposition periods and lifetime fecundity of P. oleae provided with different flowering plant species or with water only, in the anthophagous generation. ... 177 Table 8.3 Average (mean ± SE) male and female longevity, pre-oviposition and oviposition

period and lifetime fecundity of P. oleae provided with different flowering plant species or with only water, in the carpophagous generation. ... 178 Table 8.4 Average (mean ± SE) of male and female longevity, length of pre-oviposition and

oviposition periods and lifetime fecundity of P. oleae from the phyllophagous generation provided with different sugars, only water or an artificial diet. ... 179

27

Chapter 1

Chapter 1

General Introduction

Chapter 1 General Introduction

29 1.1 General Introduction

Prays oleae (Bernard, 1788) (Lepidoptera: Praydidae), is currently the principal insect pest

of olive groves in the Mediterranean Europe, and is therefore the primary target of management (Paredes et al., 2013). Although antagonized by a rich complex of natural enemies (Arambourg and Pralavorio, 1986), the impact of these beneficials is not always adequate, namely in northeastern Portugal, where Bento et al. (2001) estimated losses at up to 368 €/ha in the anthophagous generation and up to 535 €/ha in the carpophagous generation. In several regions the control of this pest depend on the use of organophosphorus and pyrethroids insecticides, with undesirable side effects, which may represent a serious constraint to the expansion of organic olive production.

On 25 September 2015, the 193 countries of the United Nations General Assembly adopted the 17 Sustainable Development Goals, and the second goal is dedicated to sustainable agriculture, and one of its targets is, “ensure sustainable food production systems and implement resilient agricultural practices, that help maintain ecosystems and progressively improve land and soil quality” (UN GA, 2015).

Moreover, the directive 2009/128/EC promotes sustainable production methods and establishes a framework to achieve a sustainable use of pesticides by reducing the risks and impacts of them on human health and environment.

For that, its first general principle include the protection and enhancement of important beneficial organisms, namely by the use of ecological infrastructures inside and outside the crops (Barzman et al., 2015).

While classical biological control was based on passive protection of existing antagonists by adequate plant protection programs and/or active release of commercially available antagonists, conservation biological control involves manipulation of the habitat to maximize the impact of natural enemies.

The goal of habitat management is to create a suitable ecological infrastructure within the agricultural landscape to provide resources for wild populations of natural enemies to enhance their impact on pests (Böller et al., 2004). Ecological infrastructures, which are mostly plant communities, provide with flowering plants the essential food sources for the maturation and reproduction of adult parasitoids as well as many predators. However, besides beneficial insects,

Chapter 1

General Introduction

30

many herbivores depend on floral food as well. The indiscriminate use of flowering species in or near crops can therefore lead to higher pest numbers.

In a study of Michigan-native flowering plants and their associated insects, herbivores and natural enemies responded similarly to various plant characteristics, albeit the relationships were weaker among herbivores (Fiedler and Landis, 2007). Given this potential duality, the choice of plants to be used in habitat management to support conservation biological control, should be chosen not only by their effects on predators and parasitoids but also by their influence on the numbers and condition of the herbivores that infest a specific crop (Sivinski, 2014). An increased awareness of this risk resulted in a new approach in conservation biological control aiming at making strategic use of plant biodiversity.

The vast majority of research on the use of flowering plants to support beneficial arthropods has focused on a few species of easily grown flowering plants with readily available seed (Fiedler

et al., 2008). Native plants can outperform recommended non-natives and also provide local

adaptation, habitat permanency, native biodiversity, reduce the risk of plants becoming weedy or invasive, and increase the potential success of the conservation investment (Alpert et al., 2000; Rejmánek, 2000; Isaacs et al., 2009).

Ideally, conservation plantings for beneficial arthropods should use plant species and genotypes native to the particular ecoregion in which they are used. As an example, some species, including Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Daucus carota L., Trifolium repens L. and Raphanus

raphanistrum L., are considered invasive in parts of their non-native ranges (USDA-NRCS, 2008;

Sivinski et al., 2011). Consequently, regional research efforts are needed to screen native plants for their potential to conserve beneficial arthropods (Isaacs et al., 2009).

The diversity and abundance of arthropods available to provide biological control in crop fields depends on the structure and composition of the surrounding landscape (Colunga-Garcia et

al., 1997; Thies et al., 2003; Schmidt and Tscharntke, 2005). Moreover, crop fields are ephemeral

habitats in which anthropogenic disturbances, such as tillage, pesticide application, and harvesting, require arthropods to frequently recolonize crops (Wissinger, 1997).

If biological pest control can be increased through conservation programs, the benefits will include increased farmer`s profit and reduced dependence on chemical pesticides (Isaacs et al., 2009).

Chapter 1 General Introduction

31

The main pillar of this approach is the conservation or introduction of plant diversity in agroecosystems (Lamichhane et al., 2016).

Thus, it seems reasonable that a first step in the addition of natural enemy-supporting plants to a particular agricultural landscape is to identify both the potential advantages and disadvantages of the various local flower-candidates (Sivinski, 2014). Agricultural producers and, ultimately, society will benefit from increased investment in understanding how to best utilize native plants in order to enhance arthropod-mediated ecosystem services (Isaacs et al., 2009).

There were plant/flower characteristics correlated to attractiveness to Lepidoptera and which might allow extrapolation to identify problematic flowers. Plants with greater floral areas tended to be more attractive, and this was also the case for hymenoptera (Sivinski et al., 2011; Al-Dobai

et al., 2012). Flower depth was also significantly related to attractiveness, and flowers pollinated

by moths often have long corolla tubes (Knudsen and Tollsten, 1993).

Because reintegration of native plants into agricultural landscapes has the potential to support multiple conservation goals, it will require the collaboration of researchers, conservation educators, and native experts (Isaacs et al., 2009).

The overall aim of the present investigation was to identify scope for improving the impact of natural enemies of P. oleae, with emphasis on Chelonus elaeaphilus Silvestri (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) and Chrysoperla carnea (Stephens) (Neuroptera: Chrysopidae), through the adoption of conservation biological control principles.

C. elaeaphilus is a common parasitoid of P. oleae in several olive-growing regions, as in

Trás-os-Montes and Beira Interior (Bento et al., 1998; Soares et al., 2005), where it can parasitize up to 79% of the carpophagous generation population (Bento et al., 2004). Chrysopid larvae are the major oophagous predators of the P. oleae accounting for over 90% predation in some regions and years (Ramos and Ramos, 1990). As in other olive-growing regions, C. carnea was the commonest species of chrysopid found in studies carried out in Trás-os-Montes olive groves (Bento

et al., 1999).

Habitat management can provide natural enemies with alternative hosts (DeBach and Rosen, 1991; Menalled et al., 1999; van Emden, 2013), shelter (Gurr et al., 1998), and non-host food (Baggen et al., 1999; Wilkinson and Landis, 2005). Both parasitoids and predators benefit from access to non-host food, especially nectar, pollen and often honeydew. At points in some parasitoid

Chapter 1

General Introduction

32

life cycles, access to sugars may be more important than host availability (Baggen and Gurr, 1998). Also predators often supplement their diets with plant resources, for instance the survival of adult

C. carnea is enhanced when access to sugar sources is available (Principi and Canard, 1984; Van

Rijn et al., 2006).

The present thesis is structured into nine chapters, seven of which correspond to papers that have been submitted, accepted or published in international scientific journals with referees. These chapters focus on specific issues that are important for the final goal of this work that is to enhance biological control of the olive moth, P. oleae, in organic olive groves by increasing functional biodiversity, so that these results can be useful to develop rational pest control and increase sustainability of this agroecosystem.

In addition to the introduction and conclusion, these chapters and the corresponding objectives are:

Second chapter, to do floristic surveys in olive groves in order to gain knowledge about flowering plant species from this agroecosystem potentially interesting to increase the conservation biological control of insect pests;

Third chapter, to survey P. oleae parasitoids, on the basis of samples collected in organic and integrated production olive groves from interior Center and North East regions of Portugal;

Fourth chapter, to assess if the olive moth, and five of its main natural enemies, can theoretically access the nectar from 21 flowering plant species previously identified in olive groves (i.e. Conopodium majus (Gouan) Loret, Daucus carota L., Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Asparagus

acutifolius L., Andryala integrifolia L., Chondrilla juncea L., Dittrichia viscosa (L.) Greuter, Sonchus asper (L.) Hill, Echium plantagineum L., Capsella bursapastoris (L.) Medik., Raphanus raphanistrum L., Lonicera hispanica Boiss. et Reut., Silene gallica L., Spergula arvensis L., Trifolium repens L, Hypericum perforatum L., Calamintha baetica Boiss. et Reut, Lavandula stoechas L., Malva neglecta Wallr., Anarrhinum bellidifolium (L.) Willd and Linaria saxatilis (L.)

Chaz.);

Fifth chapter, to evaluate the longevity and fecundity of C. carnea under laboratory conditions when fed on ten naturally occurring sugars (i.e. fructose, glucose, galactose, mannose, sucrose, trehalose, maltose, melibiose, raffinose and melezitose) compared to a control diet composed of 50% honey and 50% pollen;

Chapter 1 General Introduction

33

Sixth chapter, to evaluate the effect of providing flowers of 11 species previously identified in olive groves on the longevity and fecundity of C. carnea, in laboratory conditions;

Seventh chapter, to assess the possibilities offered by 11 native plant species from the olive grove in enhancing the fitness of the olive moth parasitoid C. elaeaphilus;

Eighth chapter, to study the theoretical compatibility between the presence of the flowering plant species in the olive grove agroecosystems with natural vegetation and the conservation biological control of P. oleae. The study was based on 15 flowering plant species: A.

integrifolia, C. bursa-pastoris, C. juncea, C. majus, D. viscosa, E. plantagineum, F. vulgare, H. perforatum, L. stoecha, L. saxatilis, M. neglecta, R. raphanistrum, S. gallica, S. asper and T. repens.

1.2 References

Al-Dobai, S., Reitz, S., Sivinski, J. 2012. Tachinidae (Diptera) associated with flowering plants.

Biological Control, 61: 230-239.

Alpert, B., Bone, E., Holzapfel. C. 2000. Invasiveness, invisibility and the role of environmental stress in the spread of non-native plants. Perspectives in Plant Ecology Evolution and

Systematics, 3: 52–66.

Arambourg, Y., Pralavorio, R. 1986. Hyponomeutidae. In: Arambourg, Y. (Ed.). Entomologie oleicole. Conseil Oleicole International. Madrid: 47-70.

Baggen, L.R., Gurr, G.M. 1998. The influence of food on Copidosoma koehleri (Hymenoptera: Encyrtidae), and the use of flowering plants as a habitat management tool to enhance biological control of potato moth, Phthorimaea opercullela (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae).

Biological Control, 11: 9–17.

Baggen, L.R., Gurr, G.M., Meats, A. 1999. Flowers in tri-trophic systems, mechanisms allowing selective exploitation by insect natural enemies for conservation biological control.

Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 91: 155-161.

Barzman, M., Bàrberi, P., Birch, A.N.E., Boonekamp, P., Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, S., Graf, B., Hommel, B., Jensen, J.E., Kiss, J., Kudsk, P., Lamichhane, J.R., Messéan, A., Moonen, A.C., Ratnadass, A., Ricci, P., Sarah, J.L., Sattin, M. 2015. Eight principles of Integrated Pest Management. Agronomy for Sustainable Development, 35: 1199-1215.10.1007/s13593-015-0327-9. [CrossRef] [ISI]

Bento, A., Torres, L.M., Lopes, J. 2001. Avaliação de prejuízos causados pela traça da oliveira,

Prays oleae (Bern.) em Trás-os-Montes. Revista de Ciências Agrárias, 24 (1-2): 89-96.

Bento, A., Cabanas, J.E., Pereira, J.A., Torres, L., Herz, A., Hassan, S.A. 2004. Effects of different attractive sources on the abundance of olive predatory arthropods and possible enhancement of their activity as predators on eggs of Prays oleae Bern. 5th International Symposium on Olive Growing. Izmir, 73 pp.

Chapter 1

General Introduction

34

Bento, A., Lopes, J., Campos, M., Torres, L. 1998. Parasitismo associado à traça da oliveira Prays

oleae Bern. em Trás-os-Montes (Nordeste de Portugal). Boletín de Sanidad Vegetal Plagas ,

24: 949-954.

Bento, A., Lopes, J., Torres, L., Passos-Carvalho, P. 1999. Biological control of Prays oleae (Bern.) by chrysopids in Trás-os-Montes region (northeastern Portugal). Acta Horticulturae, 474: 535-539.

Böller, E.F., Häni, F., Hans-Michael, P. (Eds). 2004. Ecological infrastructures: Ideabook on

functional biodiversity at the farm level. Temperate zones of Europe. Swiss Centre for

Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Switzerland, 212 p.

Colunga-Garcia, M., Gage, S.H., Landis, D.A. 1997. Response of an assemblage of Coccinellidae (Coleoptera) to a diverse agricultural landscape. Environmental Entomology, 26: 797–804. DeBach, P., Rosen, D. 1991. Biological control by natural enemies. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, UK.

Fiedler, A., Landis, D. 2007. Plant characteristics associated with natural enemy abundance at Michigan native plants. Environmental Entomology, 36: 878-886.

Fiedler, A.K., Landis, D.A., Wratten, S. 2008. Maximizing ecosystem services from conservation biological control: the role of habitat management. Biological Control, 45: 254–71.

Gurr, G.M., Van Emden, H.F., Wratten, S.D. 1998. Habitat manipulation and natural enemy efficiency, implications for the control of pests in Barbosa P. (ed.), Conservation biological

control. Academic Press, San Diego, pp 155–183.

Isaacs, R., Tuell, J., Fiedler, A., Gardiner, M., Landis, D. 2009. Maximizing arthropod-mediated ecosystem services in agricultural landscapes: the role of native plants. Frontiers in Ecology

and the Environment, 7: 196–203.

Knudsen, J., Tollsten, L. 1993. Trends in floral scent chemistry in pollination syndromes: floral scent composition in moth-pollinated taxa. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, 113: 263-284.

Lamichhane, J.R., Silke Dachbrodt-Saaydeh, Kudsk, P., Messéan, A. 2016. Toward a Reduced Reliance on Conventional Pesticides in European Agriculture. Plant Disease, 100 (1): 10-24. Menalled, F.D., Marino, P.C., Gage, S.H., Landis, D.A. 1999. Does agricultural landscape structure

affect parasitism and parasitoid diversity? Ecological Application, 9: 634–641.

Paredes, D., Cayuela, L., Gurr, G.M., Campos, M. 2013. Effect of non-crop vegetation types on conservation biological control of pests in olive groves. PeerJ 1: e116. doi: 10.7717/peerj.116. pmid:23904994

Principi, M.M., Canard, M. 1984. Feeding habits. In: M. Canard, Y. Séméria, T.R. New, Editors,

Biology of Chrysopidae, Dr. W. Junk Publishers, Boston, USA: 76–92.

Ramos, P., Ramos, M. 1990. Veinte años de observaciones sobre la depredacion oofaga en Prays

oleae Bern. Granada (España), 1970-1989. Boletín de Sanidad Vegetal Plagas, 16: 119-127.

Rejmánek, M. 2000. Invasive plants: approaches and predictions. Austral Ecology, 25: 497–506. Schmidt, M.H., Tscharntke, T. 2005. The role of perennial habitats for central European farmland

spiders. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment, 105: 235–242.

Sivinski, J. 2014. The attraction of lepidoptera to flowering plants also attractive to parasitoids (Diptera, Hymenoptera). Florida Entomologist, 97(4): 1317–1327.

Sivinski, J., Wahl, D., Holler, T., Al-Dobai, S., Sivinski, R. 2011. Conserving natural enemies with flowering plants; estimating floral attractiveness to parasitic Hymenoptera and attractions correlates to flower and plant morphology. Biological Control, 58: 208-214.

Chapter 1 General Introduction

35

Soares, M.F.D., Gomes, P.F., Simão, P.C.P.R., Veiga, C.M.F., Bento, A.A., Torres, L.M. 2005. Parasitismo associado à traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae Bernard, na Beira Interior Norte. Actas

do VII Encontro Nacional de Protecção Integrada, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra,

Coimbra, 6 e 7 de Dezembro de 2005: 371-378.

Thies, C., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Tscharntke, T. 2003. Effects of landscape context on herbivory and parasitism at different spatial scales. Oikos, 101: 18–25.

UN GA. 2015. Resolution A/RES/70/1 Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

USDA-NRCS. 2008. The Plants database. Baton Rouge, LA: National Plant Data Center. http://plants.usda.gov.

van Emden, H.F. 2013. Handbook of agricultural entomology. Wiley-Blackwell, Chichester, pp 334. ISBN 9780470659137

Van Rijn, P.C.J., Kooijman, J., Wäckers, F.L. 2006. The impact of floral resources on syrphid performance and cabbage aphid biological control. IOBC/WPRS Bulletin, 29(6): 149-152. Wilkinson, T.K., Landis, D.A. 2005. Habitat diversification in biological control: the role of plant

resources, pp. 305- 325. In: F. L. Wäckers, P.C.J. van Rijn, J. Bruin (eds.), Plant provided food for carnivorous insects. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

Wissinger, S.A. 1997. Cyclic colonization in predictably ephemeral habitats: a template for biological control in annual crop systems. Biological Control, 10: 4–15.

37

Chapter 2

Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

for natural enemies of insect pests

The content of this chapter was presented/ published in:

Nave, A., Crespí, A.L., Gonçalves, F., Campos, M., Torres, L. 2016. Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources for

natural enemies of insect pests. Ecological Research Journal (accepted) (Full paper).

Nave, A., Crespí, A., Campos, M., Torres, L.M. 2009.Infestantes do olival com interesse potencial na limitação natural da traça-da-oliveira, Prays oleae. XII Congresso da Sociedad Española de Malherbologia (SEMh) /XIX Congresso da Asociacion Latinoamericana de Malezas (ALAM)/ II Congresso Iberico de Ciencias de las Malezas(IBMC), Lisbon 10-13 November Vol 1: 39-42;ISBN: 978-972-8669-44-7 (Poster presentation).

Chapter 2

Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

Chapter 2 Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

39 Abstract

The olive groves from the Mediterranean region have a rich complex of natural enemies which regulates pest population, being estimated that there are three to four natural enemies for each olive pest.

Given this, and under a conservation biological control view, it is important the implementation of practices that maintain and enhance the reproduction, survival, and efficacy of such natural enemies. Therefore, the identification of native plant species that are selectively suitable for these natural enemies, by providing them food requirements (e.g. pollen, nectar, honeydew or alternative hosts) and shelter, is fundamental as a base for future ground cover and hedgerows selections. Thus, surveys were conducted in olive groves in one of the most important olive producing area of Portugal, in order to gain knowledge about wildflower species, from this agroecosystem potentially interesting to increase the conservation biological control.

A total of 100 species were identified from 80 genera and 29 families. The most represented families were Asteracea, Fabaceae, Brassicaceae, Poaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae and Plantaginaceae. These families are reported as favouring the populations of natural enemies of insect pests in many agroecosystems.

Results showed that resident flora of olive grove agroecosystem presents a diversity of potential enough to be exploited through as ecological infrastructure.

Ground cover from studied olive groves showed biodiversity (Margalef index = 3.6 ± 0.2), no dominance of species (Shannon-Wiener index = 2.3 ± 0.1), heterogeneity (Simpson´s index = 0.1 ± 0.01) and evenness (Hurlbert’s index = 0.92 ± 0.01).

Chapter 2

Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

Chapter 2 Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

41 Resumo

Os olivais da região do Mediterrâneo têm um rico complexo de inimigos naturais das pragas que regulam as suas populações, sendo estimado que existem três a quatro inimigos naturais para cada praga do olival.

Diante disso, e do ponto de vista da protecção biológica de conservação, é importante a implementação de práticas que mantenham e melhorem a reprodução, sobrevivência e eficácia de tais inimigos naturais. Portanto, a identificação de espécies de plantas nativas que são selectivamente adequadas para estes inimigos naturais, proporcionando-lhes os recursos alimentares (por exemplo, pólen, néctar, melada ou hospedeiros alternativos) e abrigo, é fundamental para futuras coberturas do solo e sebes. Assim, foram realizados inventários em olivais de uma das mais importantes áreas de olival de Portugal, a fim de adquirir conhecimento sobre espécies de flores silvestres, presentes neste agroecossistema, potencialmente interessante para aumentar a protecção biológica de conservação.

Um total de 100 espécies foi identificado a partir de 80 géneros e 29 famílias. As famílias mais representativas foram Asteracea, Fabaceae, Brassicaceae, Poaceae, Scrophulariaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Apiaceae, Lamiaceae e Plantaginaceae. Estas famílias são referenciadas como favorecendo as populações de inimigos naturais das pragas em muitos agroecossistemas.

Os resultados mostraram que a flora residente do ecossistema olival apresenta uma diversidade de potencial suficiente para ser explorada através de cobertura do solo, como infraestrutura ecológica.

A cobertura do solo nos olivais estudados apresentou biodiversidade (índice de Margalef = 3,6 ± 0,2), nenhuma dominância de espécies (índice de Shannon-Wiener = 2,3 ± 0,1), heterogeneidade (índice de Simpson = 0,1 ± 0,01) e uniformidade (índice de Hurlbert = 0,92 ± 0,01).

Chapter 2

Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

Chapter 2 Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

43 2.1 Introduction

The contribution of entomophagous arthropods (predators and parasitoids) in the conservation biological control of insect pests in the olive grove seems to be especially important, since these beneficial organisms are a large and relatively diversified group, whose efficiency can reach high levels in some regions (Ramos et al., 1983).

However, many entomophagous do not only feed on insects; they require other substances, both organic and inorganic (Landis et al., 2000; Lundgren, 2009), especially nectar, pollen and often honeydew.

Adults of numerous species of predators and parasitoids depend, wholly or mainly on carbohydrates as energy source (Jervis et al., 1993). Carbohydrates are essential to the good performance of these organisms, by the relevant role in critical aspects of their biology and behavior, such as longevity, fecundity (Olson and Andow, 1998) and the ability to search the host (Krivan and Sirot, 1997). Under field conditions, the natural enemies of pest`s get carbohydrates mainly from floral or extra-floral nectar and honeydew excreted by homoptera (Lundgren, 2009). Plant diversity enhances wildlife food and shelter availability (Potts et al., 2006) and maintains pest´s natural enemies, hence reducing the need for pesticides (Paredes et al., 2013; Lu

et al., 2014).

The coevolution of plants and insects allowed to establish mutual relations (Lundgren, 2009). Various studies confirm the existence of a direct link between certain phytocenoses and the abundance of predators and parasitoids, due to the supply of various nutrients contained in pollen and nectar, fundamental to the insect life cycles (Jervis et al., 1993; Colley and Luna, 2000; Casado

et al., 2002).

Therefore, plant species must be evaluated in terms of their potential interest in the increment of natural enemy populations, based on a set of criteria referred in the literature, e.g.: a) variety of plant families (Fiedler and Landis, 2007), b) attractiveness to natural enemies (Maingay et al., 1991), c) knowledge about their role on natural enemy populations (Maingay et al., 1991; Ambrosino et al., 2006), d) flowering phenology (Freeman-Long et al., 1998; Rebek et al., 2005), e) prolific production of pollen and/or nectar (Zhao et al., 1992), f) accessibility of floral resources (Baggen et al., 1999), g) presence in, or adaptation to agricultural areas (Nicholls et al., 2000), and h) multifunctional role (Rogers and Potter, 2004; Shrewsbury et al., 2004).

Chapter 2

Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

44

An appropriate structure and composition of the agricultural ecosystem, taking into account the ecological needs of the functional populations of natural enemies, coupled with a sound management of its components, could encourage pest control at levels below the economic threshold.

Regarding to the olive grove, herbaceous vegetation was associated with a consistent reduction of the abundance of serious pest of olives in the Mediterranean basin (Paredes et al., 2013). Moreover, parasitoids seems to be more abundant in organic olive groves, with cover cropping and biodiversity, than in conventional ones, with tillage combined or not with herbicide applications (Casado et al., 2002).

Recent studies suggest that, if properly selected, spontaneous flora can be valuable to provide food or shelter, for insect natural enemies, having the advantage compared to the exotic ones of being locally adapted and contributing to increase the natural biodiversity (Fiedler and Landis, 2007).

In the Mediterranean region the main insect pests of olive tree are, the olive fruit fly

Bactrocera oleae (Rossi), the olive moth Prays oleae Bernard, the olive psyllid Euphyllura olivina

Costa and the mediterranean black scale Saissetia oleae (Olivier). However, this olive pests have associated a rich natural enemy’s complex (e.g. Chrysopidae, Coccinellidae, Syrphidae and several families of Hymenoptera, especially belonging to the families of Braconidae, Chalcididae, Eulophidae, Ichneumonidae and Trichogrammatidae) which impact pest populations and whose survival, fecundity, longevity and effectiveness must be enhanced.

Thus, understanding the effects of vegetation complexity on plant–arthropod interactions is fundamental to, if is necessary, manipulate environmental spatial heterogeneity and to modify managed habitats to maintain ecosystem functioning and stability (Butler et al., 2007).

Agricultural producers and society will benefit from increased investment in understanding how to better utilize native plants to enhance arthropod-mediated ecosystem services (Isaacs et al., 2009).

Therefore, this study aimed to a) identify the species of spontaneous flora present in the natural ground cover of olive groves; b) characterize the species for the physiognomic type; c) evaluate the richness and diversity of species; and d) analyze the flora in terms of their potential to

Chapter 2 Native Mediterranean plants as potential food sources

45

improve ecosystem functional biodiversity by increasing populations of arthropods, on the basis of available literature about these groups of organisms.

2.2 Material and methods

In October and November of 2008 floristic surveys were done in 36 olive groves, with the soil covered with natural vegetation, located in the districts of Castelo Branco (39°48' N and °30' W), Guarda (40°32' N and 7°15' W), and Viseu (40°39' N and 7°54' W), in order to identify the plant species presents.

The distribution of the olive groves by district (Figure 2.1) was as follows: a) Guarda, 29 groves distributed by the counties of Mêda, Guarda, Gouveia, Seia, Trancoso, Figueira de Castelo Rodrigo, Celorico da Beira and Pinhel, b) Castelo Branco, five groves distributed by the counties of Belmonte, Covilhã and Fundão and c) Viseu, two groves, located in the county of Penedono. The diversity of characteristics from the sampled groves, allow them to be representative of the olive groves in the center and north of Portugal; different ages, young still more than 60 years, plant spacing variable, from 5 × 3 m, to 8 × 8 m, also scattered trees, from olive tree monovarietal to olive groves with several varieties (i.e. Galega, Cornicabra, Cobrançosa, Picual, Negrinha, Madural and Cordovil), and practicing Integrated Production or Organic Farming rules.

For the surveys, in each of the olive grove, 10 sampling units with 1 x 1m of surface were delimited at random. After, flowering plants were identified and the number of specimens was counted, in order to evaluate their abundance (Braun-Blanquet, 1979). Then, one plant of each species was collected and labelled for further confirmation in the laboratory, based on the keys of Iberian plants (Castroviejo, 1997). Moreover its life form was classified on the basis of the system of physiognomic types proposed by Raunkiaer (1934).

To characterise the biodiversity of the studied biotopes, four diversity indices were calculated: the Margalef richness index (d), the Shannon-Weaver diversity index (H’), Simpson’s species diversity (D), and the Hurlbert’s equitability index (E).