U

NIVERSIDADE DEL

ISBOAF

ACULDADE DEC

IÊNCIASUnravelling mechanisms of reproductive isolation

between two sister species of Iberian voles

Doutoramento em Biologia

Biologia Evolutiva

Margarida Alexandra de Sousa Carvalho Tavares Duarte

Tese orientada por:

Doutora Cristiane Bastos-Silveira

Professora Doutora Maria da Luz Mathias

Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de Doutor

U

NIVERSIDADE DEL

ISBOAF

ACULDADE DEC

IÊNCIASUnravelling mechanisms of reproductive isolation

between two sister species of Iberian voles

Doutoramento em Biologia

Biologia Evolutiva

Margarida Alexandra de Sousa Carvalho Tavares Duarte

Tese orientada por:

Doutora Cristiane Bastos-Silveira

Professora Doutora Maria da Luz Mathias

Júri:

Presidente:

• Professor Doutor Pedro Miguel Alfaia Barcia Ré Vogais:

• Doutor Gerald Heckel

• Professor Doutor Carlos Manuel Martins Santos Fonseca • Professor Doutor António Paulo Pereira de Mira

• Doutora Susana Sá Couto Quelhas Lima Mainen

• Professora Doutora Maria da Luz da Costa Pereira Mathias

• Professor Doutor Octávio Fernando de Sousa Salgueiro Godinho Paulo

Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de Doutor

Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (SFRH/BD/70646/2010; PTDC/BIA-BEC/103729/2008; UID/AMB/50017); FCT/MEC; FEDER

The Ph.D. candidate was awarded with studentship SFRH/BD/70646/2010, financed by Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia (FCT).

The present Ph.D. project was developed under PTDC/BIA-BEC/103729/2008 ”Understanding the origin and persistence of Microtus species in the Iberian Peninsula: the genetical, behavior and ecological forces” (FCT), coordinated by Cristiane Bastos-Silveira. It was also supported by Centro de Estudos de Ambiente e Mar through National (UID/AMB/50017 and FCT/MEC) and European (FEDER, within the PT2020 Partnership Agreement and Compete 2020) funds.

The present Ph.D. dissertation should be cited as:

Duarte MA (2016) Unravelling mechanisms of reproductive isolation between two sister species of Iberian voles. Dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências,

“Success is not final, failure is not fatal: it is the courage to continue that counts.”

Preliminary notes

According to the Post‐graduate Studies Regulation (Diário da República, 2.ª série, N.º 57, published on the 23th of March, 2015), the present dissertation includes papers published in ISI-indexed scientific journals and manuscripts in preparation for submission.

These papers are included in Chapters 2, 3, 4 and 5, and were formatted according to the dissertation style, except for specific requirements made by the scientific journals, such as references and measurement units.

The Ph.D. candidate is presented as the first author since it was responsible for the scientific design, data collection, analysis of the results and writing of the papers, under the supervision of Cristiane Bastos-Silveira (primary supervisor) and Professor Maria da Luz Mathias (secondary supervisor).

Lisbon, 25th of July, 2016

Table of contents

Preliminary notes ... I Acknowledgments ... III Resumo ... IX Abstract ... XV

Chapter 1 - General Introduction ... 1

1.1 The genus Microtus ... 3

1.1.1 Microtus voles of the Iberian Peninsula ... 5

1.2 Iberian sister species ... 6

1.2.1 The Lusitanian pine vole ... 8

1.2.2 The Mediterranean pine vole ... 10

1.2.3 Mating system ... 12

1.2.4 Reproductive isolation barriers ... 13

1.3 Aims and hypotheses ... 16

1.4 References ... 18

Chapter 2 - Candidate genes related to odour cues communication ... 29

2.1 Olfactory receptors ... 31

2.1.1 Abstract ... 31

2.1.2 Keywords ... 32

2.1.3 Introduction ... 32

2.1.4 Materials and methods ... 34

2.1.5 Results and discussion ... 36

2.1.6 Acknowledgments ... 43

2.1.7 References ... 43

2.1.8 Supplementary material ... 51

2.2 Major histocompatibility complex I and II ... 60

2.2.2 Keywords ... 60

2.2.3 Introduction ... 61

2.2.4 Materials and methods ... 63

2.2.5 Results and discussion ... 66

2.2.6 Acknowledgements ... 69

2.2.7 References ... 69

Chapter 3 - Urinary protein expression ... 75

3.1 Urinary protein expression ... 77

3.1.1 Abstract ... 77

3.1.2 Keywords ... 77

3.1.3 Introduction ... 78

3.1.4 Materials and methods ... 80

3.1.5 Results and discussion ... 82

3.1.6 Acknowledgments ... 86

3.1.7 References ... 86

Chapter 4 - Partner preference ... 89

4.1 Partner preference in an artificial syntopic environment ... 91

4.1.1 Abstract ... 91

4.1.2 Keywords ... 92

4.1.3 Introduction ... 92

4.1.4 Materials and methods ... 93

4.1.5 Results ... 94

4.1.6 Discussion ... 96

4.1.7 Compliance with ethical standards ... 99

4.1.8 References ... 99

4.2 Pair bonding behaviour ... 104

4.2.1 Abstract ... 104

4.2.2 Keywords ... 105

4.2.4 Materials and Methods ... 108

4.2.5 Results ... 111

4.2.6 Discussion ... 114

4.2.7 Acknowledgments ... 120

4.2.8 References ... 120

Chapter 5 - Putative sperm-binding region of zona pellucida 3 ... 129

5.1 Putative sperm-binding region of zona pellucida 3 ... 131

5.1.1 Abstract ... 131

5.1.2 Keywords ... 132

5.1.3 Introduction ... 132

5.1.4 Material and methods ... 134

5.1.5 Results ... 138

5.1.6 Discussion ... 144

5.1.7 Acknowledgements ... 146

5.1.8 References ... 147

5.1.9 Supporting information ... 156

Chapter 6 - General Discussion ... 167

6.1 Discussion & Conclusion ... 169

6.1.1 Hypothesis 1 ... 169 6.1.2 Hypothesis 2 ... 171 6.1.3 Hypothesis 3 ... 174 6.1.4 Hypothesis 4 ... 175 6.2 Future directions ... 177 6.3 References ... 178 Annex ... 187

Acknowledgments

Firstly, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Cristiane Bastos-Silveira, for her unconditional support and ability to challenge me throughout this Ph.D. project. You were always more than a supervisor and our friendship will always be treasured. Secondly, to Professor Maria da Luz Mathias for all the insightful comments and counselling provided these past years.

I will also like to thank all my fellow colleagues, particularly Patrícia Sardinha, my partner in crime at the Museu de História Natural e da Ciência (MUHNAC), for all the support during the good, the bad and the ugly; Joaquim Tapisso and Rita Monarca for all the assistance with behavioural testing and statistical analyses; and to Isabel Queirós Neves, Ana Sofia Quina and Sofia Gabriel for the encouragement during these past years.

For their support and interest I have to thank Catarina Mateus, Judite Alves, Alexandra Cartaxana and Luís Ceríaco from MUHNAC; and Isa Matos, Silke Waap, Mónica Silva and D. Branca from the Faculdade de Ciências da Universidade de Lisboa.

A special thanks is due to Gerald Heckel (Institute of Ecology and Evolution, University of Bern) for all the theoretical discussions throughout the years and for enabling me to enrich my molecular biology data with his precious Microtus samples. I would also like to thank Heidi Lischer for all the support with the repeated random haplotype sampling analysis and the sweet Susanne Tellenbach for technical assistance.

At the Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology (University of Coimbra) I would like to thank Bruno Manadas for his availability and assistance with proteomic analyses.

I also acknowledge the support of my FCULian friends Inês Silva, Ana Filipa Parreira, Ana Mónica Gabriel, Márcia Pinheiro, Fernanda Baptista, Marina Ribeiro and Frederico Rodrigues; and the Doroteias “gang”, particularly the wanderlust Susana Gasalho.

For proofreading the present dissertation I would like to thank John Lee from the Champalimaud Foundation. Thanks are also due to Micael Fonseca for custom drawing all illustrations present in each chapter’s cover page.

My sincere thanks also go to my current Champalimaud Research mates from Lima, Mainen and Renart Labs, and Vivarium and Glasswash and Media Preparation Platforms, particularly Silvana “Banas” Araújo, Susana “Sue” Valente, Diogo Matias, Luís Moreira, Raquel Tomás, Ana Margarida Nunes, João Pereira and Patrick Teca. Without their support, interest and insights the task of finishing my Ph.D. dissertation would have been much more difficult. Moreover, I would also like to thank my “handler” Susana Lima and “boss” Zachary Mainen, for giving me a warm welcome to this great institute and for supporting this last stretch of my Ph.D. marathon. It is a pleasure to wake up every day knowing that I am a part of the multidisciplinary Champalimaud Research family.

For supporting my academic and personal life unconditionally I would like to thank my parents. Without them nothing would have been possible. Also, a tight and long hug to the forth member of the family, my petit chat, the most beautiful cat that I will ever seen and that left me with eighteen years of treasured memories.

Lastly, the biggest of acknowledgments to Pedro for supporting and encouraging me throughout the Ph.D. journey and in my most recent endeavours. Having you by my side has made all the difference.

Resumo

Este projeto de Doutoramento constituiu um primeiro passo na clarificação de mecanismos de isolamento reprodutor entre duas espécies de roedores que divergiram muito recentemente, apenas há 60,000 anos: o rato-cego Microtus

lusitanicus e o rato-cego Mediterrânico Microtus duodecimcostatus. Este episódio

evolutivo constitui um dos eventos de especiação mais recentes em espécies do género Microtus.

O isolamento reprodutor é essencial ao processo de especiação entre populações divergentes e à manutenção de unidades taxonómicas distintas, como é o caso de M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus. Dois tipos de isolamento, pré- e pós-copulatório, poderão prevenir a hibridação de duas espécies. Enquanto que as barreiras pré-copulatórias previnem o comportamento reprodutor heterospecífico e promovem a cópula conspecífica, i.e. entre indivíduos da mesma espécie; as barreiras pós-copulatórias afectam a fertilização do oócito por um espermatozóide de uma espécie diferente, a viabilidade do híbrido e possível esterilidade do mesmo.

Estas espécies irmãs Ibéricas apresentam uma área de distribuição em alopatria, com M. lusitanicus mais a Norte e M. duodecimcostatus mais a Sul da Península; e em simpatria, onde ambas as espécie ocorrem, localizada no centro da Península Ibérica, cobrindo parte de Portugal e Espanha.

Dados de citocromo b e microssatélites, obtidos no decorrer do projeto PTDC/BIA-BEC/103729/2008, revelaram discordância citonuclear numa grande área de simpatria em Portugal, indicando uma introgressão histórica de DNA mitocondrial de M. duodecimcostatus para M. lusitanicus.

Um isolamento reprodutor incompleto entre estas espécies irmãs na natureza é sugerido pela existência de apenas dois possíveis híbridos numa amostragem de aproximadamente trezentos indivíduos. Esta observação é complementada por dados de escolha de parceiro, através da urina, que revelaram uma preferência por odores conspecíficos a heterospecíficos, indicando a presença de isolamento

comportamental pré-cópula. Barreiras gaméticas foram igualmente sugeridas entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus devido a um menor sucesso da reprodução heterospecífica versus conspecífica, em condições laboratoriais. Esta observação revela que a fertilização entre ambas as espécies poderá nem sempre ocorrer após a cópula, provavelmente devido a incompatibilidades no reconhecimento oócito-espermatozóide.

Consequentemente, este projeto de Doutoramento focou-se em mecanismos de isolamento reprodutor entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus, nomeadamente em barreiras comportamentais pré-copulatórias e em barreiras gaméticas pós-copulatórias. Cinco objetivos específicos foram considerados: 1) identificar genes candidatos relacionados com a comunicação através do odor; 2) analisar a expressão de proteínas na urina de ambas as espécies; 3) inferir se ambas as espécies favorecem a cópula conspecífica em oposição à heterospecífica; 4) determinar se ambas as espécies apresentam uma ligação do casal reprodutor, indicativa de um sistema monogâmico social; 5) investigar o papel da proteína de reconhecimento do espermatozóide, zona pellucida 3 como barreira de isolamento gamético.

Os resultados obtidos permitiram testar as seguintes hipóteses: 1) a comunicação através do odor é uma barreira reprodutora comportamental ativa entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus; 2) M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus preferem copular com indivíduos conspecíficos a heterospecíficos, na presença de potenciais parceiros de ambas as espécies; 3) M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus são espécies monogâmicas sociais; e 4) a região putativa de ligação ao espermatozóide do ZP3 é uma barreira de isolamento reprodutor gamética, que afecta o acasalamento heterospecífico de M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus.

Relativamente à análise de mecanismos relacionados com a comunicação através do odor, dois tipos de genes candidatos foram analisados: 1) receptores olfactivos, Olfr31 e Olfr57, ao nível das proteínas receptoras de sinal; e 2) MHCI e MHCII ao nível das proteínas emissoras de sinal. Foram ainda examinadas urinas de M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus de forma a inferir-se se existem, ou não,

proteínas urinárias específicas de espécie que possam estar a contribuir como barreiras comportamentais na escolha de parceiro. Tendo em conta a hipótese colocada, determinou-se que os receptores olfactivos Olfr31 e Olfr57 provavelmente não estão relacionados com o isolamento reprodutor de ambas as espécies, visto haver baixa variabilidade genética e ausência de seleção positiva em diversos aminoácidos localizados na zona de reconhecimento de partículas odoríferas. Devido a constrangimentos metodológicos, não foi possível aferir se MHCI e MHCII apresentam um papel relevante no isolamento reprodutor entre M.

lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus. Adicionalmente, dados de proteómica utilizando

a urina de ambas as espécies questionaram o papel das MUPs (major urinary proteins), em particular o MUP20 (Darcin), como barreiras comportamentais. Este poderá ser clarificado através da análise futura de uma maior amostragem de urinas de ambas as espécies e sexos.

Considerando a hipótese de que M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus preferem reproduzir-se conspecificamente a heterospecificamente, na presença de potenciais parceiros de ambas as espécies, foram simulados dois ambientes de sintopia artificiais com uma macho e fêmea de cada taxon. Num deles houve uma clara dominância e agressividade de M. duodecimcostatus para com M. lusitanicus, levando à morte do macho M. lusitanicus e ao cancelamento desse ambiente artificial. Duas ninhadas conspecíficas de M. duodecimcostatus nasceram durante este ambiente. Por oposição, na outra simulação de sintopia foi observada tanto cópula heterospecífica entre a fêmea M. duodecimcostatus e o macho M. lusitanicus, como conspecífica entre ambos M. lusitanicus. Enquanto ambas as fêmeas e o macho M. lusitanicus socializavam diariamente e partilhavam o ninho, o macho M.

duodecimcostatus manteve-se sempre associal e isolado dos restantes animais,

havendo criado um ninho próprio. Duas ninhadas foram geradas durante este ensaio. A genotipagem de todos os filhotes revelou que uma das ninhadas era conspecífica de M. lusitanicus e a outra heterospecífica resultante do cruzamento entre a fêmea M. duodecimcostatus e o macho M. lusitanicus. Estes resultados confirmaram parcialmente a hipótese de que M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus

preferem reproduzir-se conspecificamente, visto terem sido geradas três ninhadas conspecíficas e apenas uma heterospecífica. Creio que neste caso particular a hibridação entre estas espécies irmãs foi possível devido ao papel da variabilidade comportamental individual na escolha de parceiro. Esta possível barreira comportamental entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus em sintopia deverá ser considerada em estudos futuros.

A hipótese seguinte considera que M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus são espécies monogâmicas sociais. O sistema de acasalamento foi inferido através de ensaios de comportamento recorrendo a um olfactómetro, de forma a testar a ligação entre membros de um mesmo casal reprodutor estável através de uma escolha entre o odor do parceiro ou de um estranho, naïve ou experiente ao nível sexual. Em todos os cenários testados, à exceção de um, verificou-se uma preferência pelo odor do parceiro. A exceção foi observada quando os machos tiveram de escolher entre a parceira e uma fêmea naïve. Os resultados obtidos confirmaram a presença de uma ligação entre os membros do casal, característica de um sistema monogâmico social, com possibilidade de cópula extra-casal por parte do macho. Essa possibilidade poderá aumentar o sucesso reprodutor dos machos numa situação de aumento de recursos naturais. Assim sendo, coloco a hipótese de que na natureza, em sintopia, a monogamia social poderá atuar como barreia comportamental indireta entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus.

A barreia gamética foi inferida através da análise evolutiva da região putativa de ligação ao espermatozóide da glicoproteína do oócito zona pellucida 3, baseada em várias subfamílias de roedores da família Cricetidae. Este estudo refutou o papel desta região, localizada no exão 7, como barreia gamética entre várias espécies de cricetídeos, incluindo entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus. Era expectável encontrar uma grande variação entre os aminoácidos das duas espécies, existindo uma sequência específica de espécie, de forma a impedir fertilizações heterospecíficas. No entanto encontraram-se sequências partilhadas entre diferentes espécies, incluindo M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus, e diferentes deleções de aminoácidos na região putativa de ligação ao

espermatozóide e/ou numa zona adjacente, que poderão afectar a estabilidade da ligação entre oócito-espermatozóide e consequentemente a especificidade da fertilização. Assim sendo, estes resultados refutam a postulação que esta região da zona pellucida 3 é uma barreia de isolamento gamético.

Concluindo, os resultados deste projeto de Doutoramento sugerem que o isolamento reprodutor entre estas espécies irmãs está associado a barreiras múltiplas, e não a apenas uma, e que ainda está incompleto, permitindo a ocorrência de hibridações esporádicas na natureza. Os resultados sugerem ainda um possível papel de proteínas urinárias na discriminação ao nível de espécie através do odor; confirmam a existência de um sistema monogâmico social para ambas as espécies, podendo constituir uma barreia de isolamento comportamental indireto entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus; revelam que a variabilidade comportamental individual poderá desempenhar um papel significativo no isolamento reprodutor entre M. lusitanicus e M. duodecimcostatus; e refutam a região putativa de ligação ao espermatozóide da zona pellucida 3 como barreia gamética.

Palavras-chave: Microtus lusitanicus; Microtus duodecimcostatus; isolamento

Abstract

The present Ph.D. project constituted a first step in understanding mechanisms of reproductive isolation between two recently diverged sister species: the Lusitanian pine vole Microtus lusitanicus and the Mediterranean pine vole Microtus

duodecimcostatus.

Reproductive isolation is essential to speciation, and two types of isolation, pre- and post-mating, may prevent hybridization between two species. While pre-mating barriers prevent copulation and promote conspecific reproduction, post-mating barriers affect the success of heterospecific fertilization and hybrid viability, and potentiate its sterility.

M. lusitanicus diverged from M. duodecimcostatus approximately 60,000 years

ago, constituting one of the most recent speciation events among Microtus sp. voles. While M. lusitanicus inhabits the Northern region of the Iberian Peninsula, reaching the French Pyrenees, M. duodecimcostatus occupies Southern Iberia and part of the South of France. There is also a sympatry area of distribution, where both species occur, located in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula, covering parts of Portugal and Spain.

Analyses on cytochrome b and microsatellites have uncovered a cytonuclear discordance over a large geographic area in Portugal, indicating a historical introgression of mitochondrial DNA from M. duodecimcostatus to M. lusitanicus. An incomplete reproductive isolation in nature is also suggested between both voles since two possible hybrids were detected in a sample size of nearly three hundred individuals. Moreover, behavioural isolation was hinted at, since there is a preference for conspecific over heterospecific odour cues. The gametic isolation barrier was proposed since heterospecific mating, in laboratory conditions, is less reproductively prolific than conspecific mating. This result suggests that fertilization between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus may not always occur after copulation, probably due to incompatibilities in the sperm-oocyte heterospecific recognition.

Considering these previous findings, the present Ph.D. project focused on M.

lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus reproductive isolation, particularly on

pre-mating behavioural and post-pre-mating gametic isolation barriers. It comprises five specific aims: 1) identify candidate genes related to odour cues communication; 2) analyse the expression of urinary proteins in both species; 3) infer if both species favour conspecific to heterospecific mating; 4) determine if both species present a pair bond, indicative of a monogamous mating system; and 5) evaluate the role of the sperm-binding protein zona pellucida 3, as a gametic isolation barrier.

Four hypotheses were tested: 1) odour cues communication is an active behavioural reproductive barrier between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus; 2) M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus prefer conspecific to heterospecific mating in the presence of potential mates of both species; 3) M. lusitanicus and M.

duodecimcostatus are socially monogamous; and 4) the putative sperm-binding

region of zona pellucida 3 is a gametic isolation barrier that impairs heterospecific mating between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus.

The results of the present Ph.D. project suggest that reproductive isolation between these sister species relies on multiple barriers and is still incomplete, enabling sporadic hybridization in nature. Overall, results also indicate that urinary proteins may play a role in species-specific discrimination; confirm social monogamy as the mating system of both voles, being a possible indirect behavioural isolation barrier at syntopy; reveal that individual behavioural variability may contribute to the behavioural isolation between M. lusitanicus and

M. duodecimcostatus; and refute the putative sperm-binding region of ZP3 as a

gametic barrier.

Keywords: Microtus lusitanicus; Microtus duodecimcostatus; reproductive isolation;

Chapter 1

1.1 The genus Microtus

Voles of the speciose genus Microtus Schrank, 1798 are small herbivores that inhabit the Northern Hemisphere, mostly open grasslands, but also forests and highland habitats (Figure 1) (Getz, 1985; Hoffmann & Koeppl, 1985; Mitchell-Jones et al., 1999; Nowak, 1999).

Figure 1– Species richness distribution of Microtus genus extant taxa, across the Holarctic. Darker areas correspond to a higher richness (plotted in Quantum GIS 1.8.0, using digital distribution maps of the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, 2016).

The genus Microtus holds nearly half of the Arvicolinae species (e.g. Musser & Carleton, 1993) and are an example of a recent and rapid radiation, which occurred 1.2-2 million years ago (Mya), resulting in 65 extant species (Musser & Carleton, 1993; Chaline et al., 1999; Nowak, 1999). The only mammalian genus with similar diversity across the Holarctic is Sorex Linnaeus, 1758 (Soricidae, Insectivora), which started to differentiate approximately 11.5Mya (Fumagalli et al., 1999), a long time before Microtus.

The genus Allophaiomys Kormos, 1933, a descendant of Mimomys Forsyth-Major, 1902, seems to be the ancestor of Microtus voles (Chaline & Graf, 1988). It appeared in Southern Asia during the Late Pliocene and in Europe at the beginning of the Pleistocene (Chaline & Graf, 1988). The original Asian stock diverged into many lineages, some of which migrated to North America, through the Beringian land bridge, during the last glaciation (Chaline & Graf, 1988). European and North American species appear to have diverged directly from

indirectly (Repenning, 1992), through a morphological intermediate, similar to

Lasiopodomys Lataste, 1887. On the other hand, in Southern Asia, voles may have

diverged directly from Pliocene Mimomys (Chaline & Graf, 1988; Garapich & Nadachowski, 1996; Conroy & Cook, 1999).

Many independent colonization events have originated the current Microtus Holarctic distribution (Fink et al., 2010). Ancestors of extant Microtus species colonized the European and North American continents repeatedly, in several independent events, on similar colonization routes during their radiation (Fink et al., 2010); instead of only three independent colonization events, one per continent, as previously suggested (Brunet-Lecomte & Chaline, 1991; Chaline et al., 1999).

The genus Microtus is characterized by inconsistent systematics. Taxonomic classifications are particularly difficult due to its rapid radiation and frequent gradual variation in morphological and molecular traits between extant taxa (Mitchell-Jones et al., 1999). Some Palearctic and Nearctic fossil specimens are dated from Late Pliocene (Van der Muelen, 1978; Repenning, 1992; McKenna & Bell, 1997; Chaline et al., 1999), however paleontological information is missing for most extant species or appear relatively late (Tamarin, 1985). The oldest fossil records are dated to the Middle Pleistocene, about 0.7-0.5Mya (Rabeder, 1986; Richmond, 1996; Chaline et al., 1999), suggesting that some taxa may have speciated due to the last glaciation (e.g. Chaline & Graf, 1988; Brunet-Lecomte & Chaline, 1990). Although these fossil records are some of the most detailed, considering extant rodent genera (Gromov & Polyakov, 1977; Rabeder, 1981; Rekovets & Nadachowski, 1995), they are still incomplete in order to provide a reliable evolutionary history of this speciose genus.

This genus classification has been mostly based on paleontological and morphological characteristics, particularly through dental criteria, which allow discrimination of most taxa, both extant and already extinct, with the exception of cryptic species (Chaline, 1987). Biochemical and chromosomal data have also helped to enlighten some evolutionary and taxonomic issues (Chaline, 1987). Only

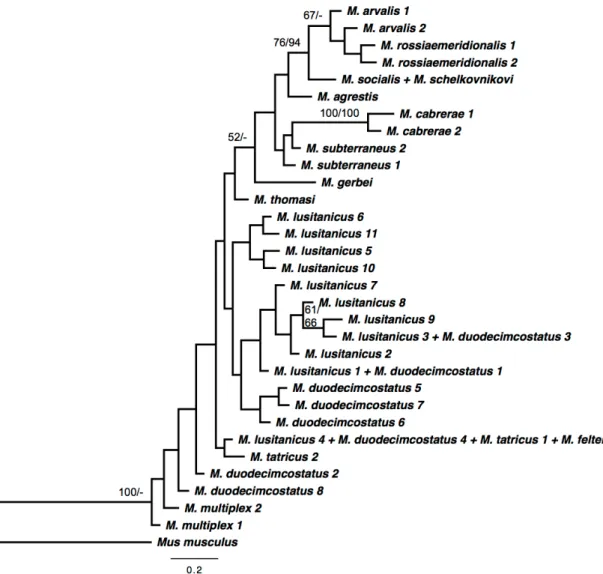

more recently has molecular data been applied in order to infer Microtus genus phylogeny and evolutionary history, using both mitochondrial (Conroy & Cook, 1999; Conroy & Cook, 2000; Galewski et al., 2006; Robovsky et al., 2008; Jaarola et al., 2004; Fink et al., 2010) and nuclear data (Galewski et al., 2006; Fink et al., 2006; Fink et al., 2007; Robovsky et al., 2008; Acosta et al., 2010a, b; Fink et al., 2010). Molecular analysis of the speciose Microtus radiation demonstrated the importance of geographic isolation, with subradiations in Europe, Asia and North America, and secondary colonizations (Fink et al., 2010). Moreover, phylogeographical studies also uncovered relatively deep divergence between parapatric evolutionary lineages within recognized taxa (Jaarola & Searle, 2002; Brunhoff et al., 2003; Fink et al., 2004; Heckel et al., 2005). These results may indicate that the taxonomic status of some of these current lineages could change to new species in the future (e.g. Microtus agrestis (Linnaeus, 1761): Hellborg et al., 2005; Beysard et al., 2012; Paupério et al., 2012; M. arvalis (Pallas, 1778): Heckel et al., 2005; Braaker & Heckel, 2009). Hence, in the recent speciose Microtus genus, there is evidence of ongoing speciation.

1.1.1 Microtus voles of the Iberian Peninsula

During the last glaciation, most of northern and central Europe was inhospitable to temperate species (Dawson, 1992). Nevertheless, there were regions in the Mediterranean peninsulas that presented a temperate climate and vegetation (Huntley, 1988; Bennett et al., 1991); hence, some species, such as

Microtus ancestors, migrated to these Mediterranean refugia and speciated.

One of these refugia, and a hotspot of endemism, is the Iberian Peninsula. It is comprised of Portugal, Spain and Andorra, and is separated from the rest of Europe by the Pyrenees. The Microtus genus is represented in this peninsula by six taxa: M. agrestis, M. arvalis, M. cabrerae Thomas, 1906, M. duodecimcostatusde Selys-Longchamps, 1839, M. gerbei (Gerbe, 1879) and M. lusitanicus (Gerbe, 1879) (IUCN, 2016). From these, only M. cabrerae and M. lusitanicus are endemic. Two sister species are also present in this refugium, being the closest relatives from their

phylogenetic clade: M. duodecimcostatus and M. lusitanicus (Jaarola et al., 2004; Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012).

1.2 Iberian sister species

The Lusitanian pine vole Microtus lusitanicus and the Mediterranean pine vole

Microtus duodecimcostatus are sister species from the Terricola subgenus, sharing a

common ancestor and a very close evolutionary relationship. These small arvicolids are classified as separate taxa based on morphological, ecological and cytogenetic differences (e.g. Cabrera, 1914; Ellerman & Morrison-Scott, 1951; Spitz, 1978; Madureira, 1981; Mathias, 1996; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Mira & Mathias, 2007; Santos et al., 2009a, Santos et al., 2009b; Santos et al., 2010; Gornung et al., 2011; Santos et al., 2011).

Persistence of a rhombus in M3 teeth suggested that their ancestor lineage was one of the first to split from Allophaiomys, approximately 1.2-1.6Mya (Chaline, 1974; Chaline & Mein, 1979); however, biochemical data do not support this assumption (Chaline & Graf, 1988). Presently, it is considered that M.

duodecimcostatus probably derived indirectly from an Iberian Allophaiomys taxon,

probably Allophaiomys chalinei Alcalde, Agustí & Villalta, 1981, while M. lusitanicus diverged from M. duodecimcostatus, approximately 60,000 years ago (Chaline, 1966, 1972; Brunet-Lecomte et al., 1987, Brunet-Lecomte & Chaline, 1991). The intermediate ancestral taxon, from which M. duodecimcostatus could have differentiated, was probably Microtus brecciensis (Giebel, 1847) (Chaline, 1987).

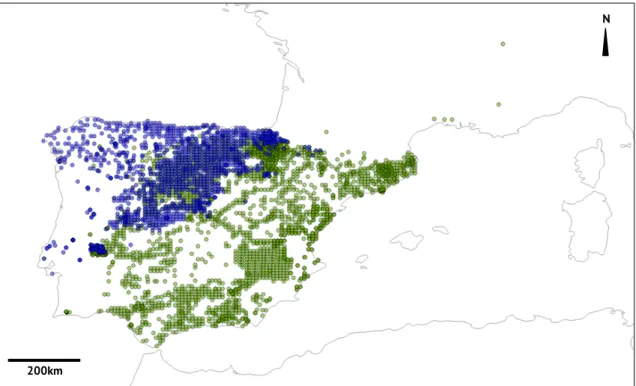

Geographically, M. lusitanicus occupies Northern Iberia, reaching the French Pyrenees (Mira & Mathias, 2007), while M. duodecimcostatus inhabits Southern Iberia and part of the South of France (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007) (Figure 2). These voles present a sympatry area of distribution, where both species occur, located in the middle of the Iberian Peninsula, covering parts of Portugal and Spain, reaching the Pyrenees (Madureira, 1984; Mitchell-Jones et al., 1999; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Mira & Mathias, 2007) (Figure 2).

Figure 2– Capture locations of M. lusitanicus (blue) and M. duodecimcostatus (green) based on geographical coordinated available on the Global Biodiversity Information Facility and

Bastos-Silveira and colleagues (2012) (plotted in Quantum GIS 1.8.0).

M. lusitanicus allopatric populations present higher M1 teeth morphological

variability than M. duodecimcostatus, suggesting that M. lusitanicus has possibly occupied a broader range of distribution in the past and that ecological competition may be occurring in the sympatry areas, between both species (Brunet-Lecomte et al., 1987).

M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus present the same karyotype 2n=62,

differing in sex chromosome morphology, constitutive heterochromatin, rDNA sites and satDNA patterns (Gornung, 2011).

A mitochondrial cytochrome b (Cytb) phylogeny on the Microtus genus revealed 4-5% genetic divergence between allopatric M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus individuals (Jaarola et al., 2004). This is the lowest genetic divergence found among Microtus taxonomically recognized taxa (Jaarola et al., 2004). More recently, Cytb and microsatellites analyses have discovered a cytonuclear discordance over a large geographic area in Portugal, suggesting a historical introgression of mitochondrial DNA from M. duodecimcostatus to M. lusitanicus

200km

(Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012). This study also disclosed a relatively advanced speciation process, based on two clear microsatellites genetic clusters, composed of allopatric and sympatric individuals, corresponding to each species morphologically identified individuals.

Concerning nuclear molecular markers, it has been suggested that the p53 gene is involved in the divergence between both sister voles (Quina et al., 2015), possibly due to its association with ecological stress such as hypoxia, and consequently to a fossorial life-style.

1.2.1 The Lusitanian pine vole

Natural populations of M. lusitanicus are organized in small family groups, which occupy complex burrow systems, excavated using the feet and incisor teeth (Mira & Mathias, 2007). Underground galleries consist of superficial (≈15cm) and deeper tunnels (<40cm), with cameras for the nest or storing food (Mira & Mathias, 2007).

M. lusitanicus reaches 77.5-105mm and 14-19g (Mira & Mathias, 2007). The

body shape of this vole reveals a semi-fossorial life-style. Its cylindrical body is covered by a dark grey to sepia pelage in the back and exhibiting a grey belly (Figure 3), where it presents two pairs of inguinal nipples.

The large head terminates with a blunt snout and a small mouth, with slightly projecting upper incisors. Coherently to its subterranean living, M. lusitanicus has small eyes, ears (6.5-10mm) and feet (13-16mm) (Figure 3).

Females reach sexual maturity at 35 days of age, while the sexual maturation of males is only reached at 50 days (Mira & Mathias, 2007). In nature, the number of embryos per litter varies from one to five (Madureira, 1984). Pups are born naked and blind, weighing about 1.5g and measuring 15mm (Mira & Mathias, 2007). Hair begins to appear within three days (Figure 4) and after two weeks they look like miniature adults. Captive births occur every 28 days and a post-partum oestrus and gestation lasts 22-24 days (Mira & Mathias, 2007).

Figure 4– Photograph of three M. lusitanicus pups, one week old, from the animal facility colony

(see Chapter 4) © Duarte, M.A.

The Lusitanian pine vole occupies diverse habitats, ranging from meadows, pastures, riversides and woods to agricultural areas, such as apple orchards and carrot crops (Mathias, 1999; Mira & Mathias, 2007; Santos, 2009). Its diet varies throughout the year. In the winter and spring M. lusitanicus eats mostly leaves and stems, while during the summer and autumn it consumes mainly subterranean parts of herbaceous plants, showing a preference for geophytes (Mathias, 1999; Mira & Mathias, 2007).

Studies on population dynamics in natural habitats are inexistent; however, in fruit orchards, common densities range from 100-200 individuals per hectare, exceeding 300 individuals per hectare in extremely favourable conditions (Mira & Mathias, 2007). Occasionally, M. lusitanicus is considered a pest when it reaches

high densities, leading to a 10-15% loss in fruit orchards (Bäumler et al., 1984; Mira & Mathias, 2007). This situation is enabled by sprinkler irrigation, a very common practice that promotes the growth of weeds near the tree trunk, leading to an increase of moisture and soil disaggregation, an optimal condition for this vole.

M. lusitanicus is a usual prey of the barn owl Tyto alba (Scopoli, 1769), tawny

owl Strix aluco Linnaeus, 1758 and some small/medium sized terrestrial carnivores (Mira & Mathias, 2007).

1.2.2 The Mediterranean pine vole

M. duodecimcostatus is bigger and more robust than M. lusitanicus, reaching

80-110mm and weighing 19-32g (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Coherently to its subterranean living, and similarly to M. lusitanicus, it presents small eyes, ears (7.5-10mm) and feet (14.5-18.5mm) (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Its pelage is yellowish brown tone, with a characteristic ochre edge separating the back from the belly, where it exhibits two pairs of inguinal nipples, like its sister species (Figure 5).

Figure 5– Photograph of an adult M. duodecimcostatus from the animal facility colony (see Chapter 4) © Duarte, M.A.

Still, the light and dark shades of its pelage vary by area of distribution (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). The 23-35mm tail is grey, unlike M. lusitanicus’ which is always bicoloured (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). M. duodecimcostatus also features a strong neck musculature, prominent upper incisors, developed premaxilla and diastema, revealing that it is perfectly adapted to a semi-fossorial life-style (Madureira, 1982; Mathias, 1990).

This vole becomes sexually mature at 60-70 days of age (Mira, 1999). The breeding season is variable and gestation lasts 24 days (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Pups are born naked and blind, weighing 2-3g (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Two-week old pups present the appearance of an adult, similarly to M. lusitanicus. In nature, the number of embryos per litter ranges from one to five (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007) (Figure 6).

Figure 6– Photograph of two M. duodecimcostatus pups, three days old, from the animal facility

colony (see Chapter 4) © Duarte, M.A.

In terms of behaviour, M. duodecimcostatus is characterised by being more aggressive and less social than M. gerbei (Gerbe, 1879). M. duodecimcostatus also uses substrate-borne signals more commonly than acoustic repertoires, conversely to less aggressive M. gerbei (Giannoni et al., 1997).

This Iberian vole occupies both natural and agricultural areas of Mediterranean influence, being conditioned by the existence of stable, moist, herbaceous and easy to dig soils (Mira & Mathias, 1994; Paradis, 1995; Mira, 1999; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Santos, 2009). Its diet is mostly based on subterranean plant parts, although aerial parts may also be consumed (Borghi & Giannoni, 1997; Cotilla &

Palomo, 2007). Analogously to M. lusitanicus, there are reports of high consumption of geophytes (Soriguer & Amat, 1980), namely the subterranean parts of Oxalis pes-caprae Linnaeus 1753 (Bäumler et al., 1984; Mira 1999).

In normal conditions, M. duodecimcostatus presents densities of 100-400 individuals per hectare, whereas with favourable conditions, such as in irrigated crops, it can reach high annual average densities of 390 individuals per hectare (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). This can be extended to 900 individuals per hectare in extraordinary favourable conditions (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). In such scenarios M.

duodecimcostatus can be considered a pest and may lead to 5-10% loss in fruit

orchards (Bäumler et al., 1984; Vinhas, 1993; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007).

Its complex burrows comprise tunnels varying between 10-50cm of depth, which may increase to 1m during summer, when M. duodecimcostatus searches for soil moisture (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Galleries are highly branched and usually have a single nest for the family group and chambers for storing food, as M.

lusitanicus (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007). Galleries of both voles can be differentiated

because M. duodecimcostatus leave small monticules of soil near de openings, while M. lusitanicus do not (Purroy & Varela, 2005; Santos et al., 2009b).

The underground habits of M. duodecimcostatus are a very effective defensive strategy, so that it can only be caught when surfacing, by predators such as Tyto

alba and small/medium sized carnivores, similarly to M. lusitanicus (Cotilla &

Palomo, 2007).

1.2.3 Mating system

Natural populations of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus present a balanced sex ratio (Paradis & Guédon, 1993), K selection strategy (Guédon et al., 1991b; Guédon & Pascal, 1993; Ventura et al., 2010) and reduced litter size (1-5 pups) (Guédon et al., 1991a, b).

Spatial overlap and similar home range for both sexes were observed in M.

Krebs, 1991; Santos et al., 2010). This vole lives in small groups, composed of a couple and its pups, and with nests shared by males and females, or one female and one sub-adult (Mira & Mathias, 2007; Santos, 2009).

M. duodecimcostatus is also socially organized in small family groups (Paradis &

Guédon, 1993; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007) and, similarly to M. lusitanicus (Madureira, 1982; Heske & Ostfeld, 1990; Ventura et al., 2010), presents a sexual monomorphism in terms of adult weight (Mira, 1999) and relatively small testis in adult males (Montoto et al., 2011).

These ecological and reproductive characteristics suggest that both sister species present a monogamous mating system.

1.2.4 Reproductive isolation barriers

Reproductive isolation is essential to speciation (Dobzhansky, 1937; Mayr, 1942; Mayr, 1970). Biological, morphological, phylogenetic and genetic species concepts agree that reproductive isolation mechanisms are fundamental to recognize a diverging population as a new species (Cracraft, 1997; Baker & Bradley, 2006); thus it is important to analyse how heterospecific mating is avoided. Two types of isolation may act against hybridization between two species: pre-mating and post-mating reproductive barriers (Coyne & Orr, 2004).

Pre-mating barriers prevent copulation and promote conspecific reproduction: • Geographical isolation: species are separated by a physical barrier, such as

a river or a mountain;

• Ecological/spatial isolation: species do not meet because they inhabit different habitats, even if they occur in the same geographical region; • Temporal isolation: species present different sexually active periods; • Behavioural isolation: potential mates meet, but show a preference for

conspecifics over heterospecifics.

On the other hand, post-mating barriers affect fertilization, viability and sterility:

• Mechanical isolation: copulation is attempted, but is physically impossible, due to incompatible genitalia;

• Gametic isolation: the female immune system attacks the heterospecific sperm, after copulation; or gametes are incompatible and fertilization does not occur;

• Zygotic mortality: the egg is fertilized, but the zygote does not develop; • Hybrid unviability: the hybrid embryo forms, but with a reduced viability; • Hybrid sterility: the hybrid is viable, but as an adult it is sterile;

• Hybrid breakdown: first generation (F1) is viable and fertile, but further hybrid generations (second generation and backcrosses) may be unviable or sterile.

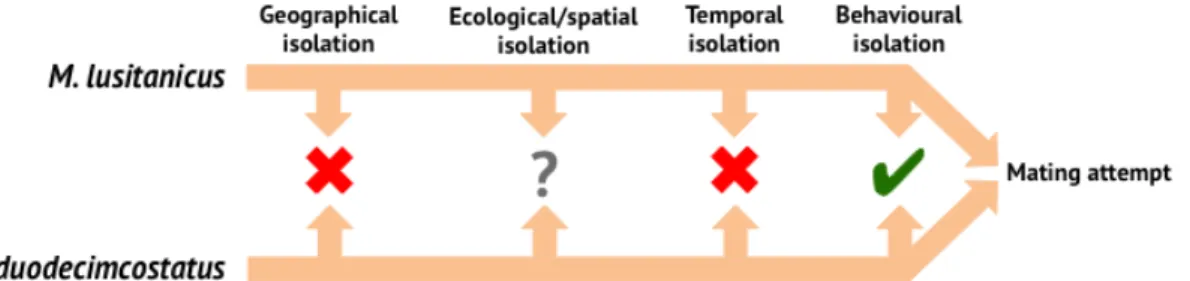

Sister species M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus share a considerable sympatry area (Figure 2). Additionally, physical barriers, such as mountains and rivers, do not seem to affect the distribution of these voles, because they inhabit low and high altitude locations (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Mira & Mathias 2007) and are proficient swimmers (Giannoni, 1993, 1994). Thus, it is very unlikely that geographical isolation acts as a reproductive barrier between these taxa (Figure

7).

Ecological/spatial isolation is also improbable because M. lusitanicus and M.

duodecimcostatus inhabit similar habitats (Mira & Mathias, 1994; Paradis, 1995;

Mathias, 1999; Mira, 1999; Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Mira & Mathias, 2007) and occurred in syntopy in the past, since fossils from both voles were discovered in the Caldeirão cave (Tomar, Portugal) (Póvoas et al., 1992) and in the la Buena Pinta cave (Pinilla del Valle, Spain) (López-García, 2008) (Figure 7). Nevertheless, it is unknown if in the present day there are syntopic locations as well.

Furthermore, both species present similar sexually active periods (Cotilla & Palomo, 2007; Mira & Mathias, 2007), showing that temporal isolation does not seem to affect M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus reproductive isolation (Figure 7).

Conversely to the previous barriers, pre-mating behavioural isolation has been suggested by a preference for conspecific individuals over heterospecific (Soares, 2013) (Figure 7).

Figure 7– Pre-mating reproductive barriers involved in M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus reproductive isolation. Cross = absent; check = present; ? = undetermined.

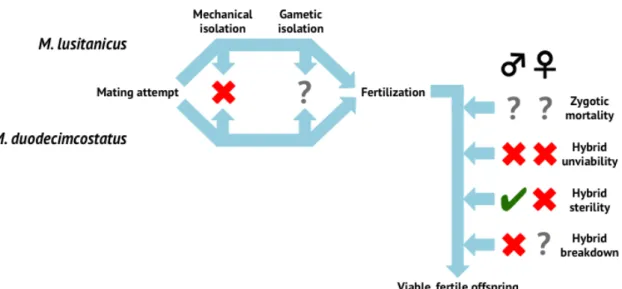

Regarding post-mating barriers, M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus can produce F1 hybrids in captivity (Wiking, 1976; Soares, 2013) and nature (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012), reaching adulthood (Soares, 2013), revealing that mechanical isolation and the hybrid unviability barrier are very implausible (Figure 8). Zygotic mortality cannot be, however, discarded, since embryonic data is currently unavailable.

Male hybrids are infertile (Soares, 2013), according to the Haldane rule (Haldane, 1922), making further hybrid generations improbable, being coherent to the results presented by Bastos-Silveira and colleagues (2013) (Figure 8). These observations indicate that the hybrid sterility barrier is active and, consequently, the hybrid breakdown barrier is absent (Figure 8). Concerning the female hybrids, it is known that they are fertile (Soares, 2013), but additional data on second generation and backcrosses fertility is needed to discard the hybrid breakdown barrier for this gender (Figure 8).

Lastly, a partial gametic isolation seems to exist, because M. lusitanicus and M.

duodecimcostatus can produce F1 hybrids, both in the lab (Wiking, 1976) and in

nature (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012), however heterospecific mating, in laboratory conditions, is less productive in terms of reproductive success than conspecific

mating (Soares, 2013), suggesting that fertilization may not always occur (Figure

8).

Figure 8– Post-mating reproductive barriers involved in M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus reproductive isolation. Barriers after a successful fertilization are specified per gender. Cross = absent; check = present; ? = undetermined.

Hence, both pre-mating and post-mating barriers seem to be responsible for M.

lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus reproductive isolation (Figure 7 and 8).

1.3 Aims and hypotheses

Considering that M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus incomplete reproductive isolation in nature seems to be associated to more than one barrier, possibly related to behavioural (pre-mating) and gametic isolation (post-mating), the present Ph.D. project comprised five specific aims:

• Identify candidate genes related to odour cues communication (Chapter

2);

• Analyse the expression of urinary proteins in both species (Chapter 3); • Infer if both species favour conspecific to heterospecific mating (Chapter

4 – 4.1);

• Evaluate the role of the sperm-binding protein ZP3 (zona pellucida 3), as a gametic isolation barrier (Chapter 5).

The results obtained enabled to test the following hypotheses:

• Hypothesis 1: Odour cues communication is an active behavioural reproductive barrier between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus. Most mammals rely on chemosensory systems for communicating in a social context, either intra- or inter-specifically, using odour cues excreted in urine, faeces, saliva, sweat or milk (reviewed in Wyatt, 2003; Liberles, 2014). Hence, for the present hypothesis, a double approach was performed and focused both on odour cues (major histocompatibility complex I and II peptides) and respective receptors (olfactory receptors) to infer their potential role in the pre-mating reproductive isolation between

M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus. In addition, proteomic analyses on

the urine of M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus were performed in order to test the possible role of particular urinary proteins in odorous communication associated with species-specific mate choice.

• Hypothesis 2: M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus prefer conspecific to heterospecific mating in the presence of potential mates of both species. It is known that these voles can produce F1 hybrids in captivity (Wiking, 1976; Soares, 2013) and nature (Bastos-Silveira et al., 2012). However, hybridization in nature is a very rare event and in captivity it is only possible because either the subjects mate heterospecifically, “forced”, or remain sexually naïve. Thus, to test the present hypothesis two artificial syntopic environments were established, for the first time, and populated with animals from each species and genders. The generated litters were genotyped in order to determine the maternal/paternal origin, and consequently if hybridization occurred or only conspecific mating was favoured.

• Hypothesis 3: M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus are socially monogamous.

Ecological and reproductive characteristics suggest that both sister species present a monogamous mating system (e.g. Madureira, 1982; Heske & Ostfeld, 1990; Guédon et al., 1991a, b; Guédon & Pascal, 1993; Paradis & Guédon, 1993; Mira, 1999; Santos, 2009; Ventura et al., 2010; Santos et al., 2010; Montoto et al., 2011). Nevertheless, behaviour assays, such as partner preference and selective aggression tests, and fieldwork paternity inference, had not been performed until the present day in order to clarify the type of monogamy exhibited by both voles. Here, partner preference tests were performed, using urinary and faecal odour cues, in order to determine if M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus conspecific couples reveal a pair bond, indicative of social monogamy.

• Hypothesis 4: The putative sperm-binding region of ZP3 is a gametic isolation barrier that impairs heterospecific mating between M. lusitanicus and M. duodecimcostatus.

Mating between subjects of both species, in captivity, is less reproductively successful than between conspecifics (Soares, 2013). This observation suggests that fertilization of heterospecific gametes may not always occur. Therefore, in this hypothesis, the putative sperm-binding region of the ZP3 was tested as one of the control mechanisms that affect putative hybridizations after successful mating. This region is historically related to species-specific fertilization (Wassarman & Litscher, 1995; Wassarman, 1999; Wassarman et al., 2005); thus, it presents a potential role as a gametic barrier.

1.4 References

Acosta MJ, Marchal JA, Romero-Fernández I, Megías-Nogales B, Modi WS, Sánchez Baca A (2010a) Sequence analysis and mapping of the Sry gene in species of the subfamily Arvicolinae (rodentia). Sex Dev 4(6):336–347

Characterization of the satellite DNA Msat-160 from species of Terricola (Microtus) and Arvicola (Rodentia, Arvicolinae). Genetica 138(9-10):1085–1098

Baker RJ, Bradley RD (2006) Speciation in mammals and the genetic species concept. J Mammal 87(4):643–662

Bastos-Silveira C, Santos SM, Monarca R, Mathias ML, Heckel G (2012) Deep mitochondrial introgression and hybridization among ecologically divergent vole species. Mol Ecol 21:5309–5323

Baümler VW, Naumann-Etienne C, Godinho J, Grilo C, Sezinando T, Vinhas A (1984) Schadliche feldnager in Portugal. Anz Schadlingskde, Pflazenschutz, Umweltschutz 57:134–138

Bennett KD, Tzedakis PC, Willis KJ (1991) Quaternary refugia of north European trees. J Biogeogr 18:103–115

Beysard M, Perrin N, Jaarola M, Heckel G, Vogel P (2012) Asymmetric and differential gene introgression at a contact zone between two highly divergent lineages of field voles (Microtus agrestis). J Evol Biol 25:400–408

Borghi CE, Giannoni SM (1997) Dispersal of geophytes by mole-voles in the Spanish Pyrenees. J Mammal 78:550–555

Braaker S, Heckel G (2009) Transalpine colonisation and partial phylogeographic erosion by dispersal in the common vole Microtus arvalis. Mol Ecol 18:2518–2531

Brunet-Lecomte P, Chaline J (1991) Morphological evolution and phylogenetic relationships of the European ground voles (Arvicolidae, Rodentia). Lethaia 24(1):45–53

Brunet-Lecomte P, Brochet G, Chaline J, Delibes M (1987) Morphologie dentaire comparée de Pitymys lusitanicus et Pitymys duodecimcostatus (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) dans le nord-ouest de l'Espagne. Mammalia 51:145–158

Brunhoff C, Galbreath KE, Fedorov VB, Cook JA, Jaarola M (2003) Holarctic phylogeography of the root vole (Microtus oeconomus): implications for late Quaternary biogeography of high latitudes. Mol Ecol 12(4):957–968

Cabrera A (1914) Fauna Ibérica: Mamíferos. Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid

Chaline J (1966) Une exemple d’évolution chez les arvicolids (Rodentia): les lignées Allophaiomus-Pitymus et Microtus. C R Acad Sci Hebd Seances Acad Sci D 263(17):1202–1204

Chaline J (1972) Le role des Rongeurs dand l’éboration d’une biostratigraphie et d’une stratigraphie climatique fine du Quaternaire. Mém Bur Rech Géol Min

77:275–379

Chaline J (1974) Un nouveau critère d’étude des Mimomys, et les rapports de

Mimomys occitanus, Mimomys stehlini et de Mimomys polonicus (Arvicolidae,

Rodentia). Acta zool cracov 19:337–356

Chaline J (1987) Arvicolid Data (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) and Evolutionary Concepts. Evol Biol 21:237–310

Chaline J, Graf J-D (1988) Phylogeny of the Arvicolidae (Rodentia): Biochemical and Paleontological Evidence. J Mammal 69(1):22

Chaline J, Mein P (1979) Les Rongeurs et l’évolution. Doin Éditeurs, Paris

Chaline J, Brunet-Lecomte P, Montuire S, Viriot L, Courant F (1999) Anatomy of the arvicoline radiation (Rodentia): palaeogeographical, palaeoecological history and evolutionary data. Ann Zool Fennici 36(4): 239–267

Conroy CJ, Cook JA (1999) MtDNA evidence for repeated pulses of speciation within arvicoline and murid rodents. J Mamm Evol 6(3):221–245

Conroy CJ, Cook JA (2000) Molecular Systematics of a Holarctic Rodent (Microtus: Muridae) J Mammal 81(2):344–359

Cotilla I, Palomo LJ (2007) Microtus duodecimcostatus (de Selys-Longchamps, 1839). In: Palomo LJ, Gisbert J, Blanco JC (eds) Atlas y libro rojo de los mamíferos terrestres de España. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Madrid, pp 422–425

Coyne JA, Orr HA (2004) Speciation. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland

Cracraft J (1997) Species concepts in systematics and conservation biology: an ornithological viewpoint. In: Claridge MF, Dawah HA, Wilson MR (eds) Species: the units of biodiversity. Chapman & Hall; London

Dawson AG (1992) Ice Age Earth: Late Quaternary Geology and Climate. Routledge, London and New York

Dobzhansky T (1937) Genetics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York

Ellerman JR, Morrison-Scott TCS (1951) Check list of Palearctic and Indian mammals. British Museum, London

Fink S, Excoffier L, Heckel G (2004) Mitochondrial gene diversity in the common vole Microtus arvalis shaped by historical divergence and local adaptations. Mol Ecol 13(11):3501–3514

Fink S, Excoffier L, Heckel G (2006) Mammalian monogamy is not controlled by a single gene. P Natl Acad Sci USA 103(29):10956–10960

Fink S, Excoffier L, Heckel G (2007) High variability and non-neutral evolution of the mammalian arginine vasopressin receptor. BMC Evol Biol 7, e176

Fink S, Fischer MC, Excoffier L, Heckel G (2010) Genomic Scans Support Repetitive Continental Colonization Events during the Rapid Radiation of Voles (Rodentia: Microtus): the Utility of AFLPs versus Mitochondrial and Nuclear Sequence Markers. Syst Biol 59:548–572

Fumagalli L, Taberlet P, Stewart DT, Gielly L, Hausser J, Vogel P. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of Sorex shrews (Soricidae: insectivora) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence data. Mol Phylogenet Evol 11(2):222–235

Galewski T, Tilak MK, Sanchez S, Chevret P, Paradis E, Douzery EJ (2006) The evolutionary radiation of Arvicolinae rodents (voles and lemmings): relative contribution of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies. BMC Evol Biol 6:80.

Garapich A, Nadachowski A (1996) A contribution to the origin of Allophaiomys (Arvicolidae, Rodentia) in Central Europe: the relationship between Mimomys and

Allophaiomys from Kamyk (Poland). Acta zool craoc 39(1):179–184

Guédon G, Pascal M (1993) Dynamique de population du campagnol provençal (Pitymys duodecimcostatus de Sélys-Longchamps, 1839) dans deux agrosystémes de la région montpelliéraine. Rev Ecol – Terre Vie 48:375–398

(Pitymys duodecimcostatus de Sélys-Longchamps, 1839) (Rongeurs, Microtidés) I. La reproduction. Mammalia 55:97–106

Guédon G, Pascal M, Mazouin F (1991b) Le campagnol provençal en captivité (Pitymys duodecimcostatus de Sélys-Longchamps, 1839) (Rongeurs, Microtidés) II. La croissance. Mammalia 55:397–406

Getz LL (1985) Habitats. In: Tamarin RH (ed) Biology of New World Microtus. The American Society of Mammalogists, Special Publication 8, pp. 286–309

Giannoni SM, Borghi CE, Martinezrica JP (1993) Swimming ability of a fossorial Iberic vole Microtus (Pitymys) lusitanicus (Rodentia, Microtinae). Mammalia 57(3):337–340

Giannoni SM, Borghi CE, Martinezrica JP (1994) Swimming ability of the Mediterranean pine vole Microtus (Terricola) duodecimcostatus. Acta Theriol 39(3):257–265

Giannoni SM, Marquez R, Borghi CE (1997) Airborne and substrate borne communications of Microtus (Terricola) gerbei and M. (T.) duodecimcostatus. Acta Theriol 42(2):123–141

Gornung E, Castiglia R, Rovatsos M, Marchal JA, Díaz de la Guardia-Quiles R, Sanchez A (2011) Comparative cytogenetic study of two sister species of Iberian ground voles, Microtus (Terricola) duodecimcostatus and M. (T.) lusitanicus (rodentia, cricetidae). Cytogenet Genome Res 132(3):144–150

Gromov V.J, Polyakov IY (1977) Fauna of the SSSR: Mammals III, 8: voles (Microtinae). Nauka, Leningrad

Haldane JBS (1922) Sex ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J Genet 12(2):101–109

Heckel G, Burri R, Fink S, Desmet J-F & Excoffier L (2005) Genetic structure and colonization processes in European populations of the common vole Microtus

arvalis. Evolution 59(10):2231–2242

Hellborg L, Gündüz I, Jaarola M (2005) Analysis of sex-linked sequences supports a new mammal species in Europe. Mol Ecol 14(7):2025–2031

Heske EJ, Ostfeld RS (1990) Sexual dimorphism in size, relative size of testes, and mating systems in North American voles. J Mamm 71(4):510–519

Hoffmann RS, Koeppl JW (1985) Zoogeography. In: Tamarin RH (ed) Biology of New World Microtus. The American Society of Mammalogists, Boston, pp 84–115

Huntley B (1988) Glacial and Holocene vegetation history: Europe. In: Huntley B, Webb T III (eds) Vegetation History, Kluwer, Dordrecht

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species (2016) http://www.iucnredlist.org

Jaarola M, Searle JB (2002) Phylogeography of field voles (Microtus agrestis) in Eurasia inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Ecol 11(12):2613–2621

Jaarola M, Martínková N, Gündüza I, Brunhoff C, Zima J, Nadachowski A, Amori G, Bulatova NS, Chondropoulos B, Fraguedakis-Tsolis S, González-Esteban J, López-Fuster MJ, Kandaurov AS, Kefelioğlu H, Mathias ML, Villate I, Searle JB (2004) Molecular phylogeny of the speciose vole genus Microtus (Arvicolinae, Rodentia) inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequences. Mol Phylogenet Evol 33(3):647–663

Lambin X, Krebs C.J (1991) Spatial organization and mating system of Microtus

townsendii. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 28:353–363

Liberles SD (2014) Mammalian pheromones. Annu Rev Physiol 76:151-175 López-García JM, Blain HA, Cuenca-Bescós G, Arsuaga JL (2008) Chronological, environmental, and climatic precisions on the Neanderthal site of the Cova del Gegant (Sitges, Barcelona, Spain). J Hum Evol 55(6):1151−1155

MacGuire B, Pissuto T, Getz LL (1990) Patterns of visitation in prairie voles (Microtus ochrogaster) reveal a role for males in population regulation. In: Tamarin RH et al. (eds) Social Systems and Population Cycles in Voles. Advances in Life Sciences, Birkhäuser Verlag, Basel, pp 89–100

Madison DM (1980) An integrated view of the social biology of Microtus

pennsylvanicus. Biologist 62:20–33

Madureira ML (1981) Discriminant analysis in portuguese pine voles: Pitymys

lusitanicus Gerbe and Pitymys duodecimcostatus de Sélys-Longchamps (Mammalia:

Madureira ML (1982) New data on the taxonomy of portuguese Pitymys. Arq Mus Bocage A I:341–368

Madureira ML (1984) A biologia de Microtus (Pitymys) duodecimcostatus de Sélys-Longchamps, 1839 e M. (P.) lusitanicus Gerbe, 1879 em Portugal (Arvicolidae, Rodentia): taxonomia, osteologia, ecologia e adaptações. Dissertation, Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa

Mathias ML (1990) Morphology of the incisors and the burrowing activity of Mediterranean and Lusitanian Pine Voles (Mammalia, Rodentia). Mammalia 54: 301–306

Mathias ML (1996) Skull size variability in adaptation and speciation of the semifossorial pine voles Microtus duodecimcostatus and M. lusitanicus (Arvicolidae, Rodentia). In: Proceedings of The First Congress of Mammalogy, Museu Nacional de História Natural, Museu Bocage, Lisbon, pp 271–286

Mathias ML (1999) Guia dos Mamíferos Terrestres de Portugal Continental, Açores e Madeira. Instituto da Conservação da Natureza, Lisboa

Mayr E (1942) Systematics and the origin of species. Columbia University Press, New York

Mayr E (1970) Populations, species, and evolution. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

McKenna MC, Bell SK (1997) Classification of mammals; above the species level. Columbia University Press, New York

Mira A (1999) Ecologia do rato-cego-mediterrânico, Microtus (Terricola)

duodecimcostatus (Rodentia, Muridae), em pomares de citrinos. Dissertation,

Faculdade de Ciências, Universidade de Lisboa, Lisboa

Mira A, Mathias ML (1994) Conditions controlling the colonization of an orange orchard by Microtus duodecimcostatus (Rodentia, Arvicolidae). Pol Ecol Stud 20:249–255

Mira A, Mathias ML (2007) Microtus lusitanicus (Gerbe, 1879). In: Palomo LJ, Gisbert J, Blanco JC (eds) Atlas y libro rojo de los mamíferos terrestres de España. Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Madrid, pp 418–421

Mitchel-Jones AJ, Amori G, Bogdanowicz W, Kryšrufek B, Reijnders PJH, Spitzenberger F, Stubbe M, Thissen JBM, Vohralík V, Zima J (1999) The Atlas of European Mammals. T & AD Poyser, London

Montoto LG, Magaña C, Tourmente M, Martín-Coello J, Crespo C, Luque-Larena JJ, Gomendio M, Roldan ERS (2011) Sperm competition, sperm numbers and sperm quality in muroid rodents. PLoS One 6(3):e18173

Musser GM, Carleton MD (1993) Family Cricetidae. In: Wilson DE, Reeder DM (eds) Mammal species of the world: a taxonomic and geographic reference. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, pp 955–1189

Nowak RM (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World. Sixth Edition. Volume II. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore

Paradis E (1995) Survival, immigration and habitat quality in the Mediterranean pine vole. J Anim Ecol 64:579–591

Paradis E, Guédon G (1993) Demography of a Mediterranean microtine: the Mediterranean pine vole, Microtus duodecimcostatus. Oecologia 95:47–53

Paupério J, Herman JS, Melo-Ferreira J, Jaarola M, Alves PC, Searle JB (2012) Cryptic speciation in the field vole: a multilocus approach confirms three highly divergent lineages in Eurasia. Mol Ecol 21:6015–6032

Póvoas L, Zilhão J, Chaline J, Brunet-Lecomte P (1992) La faune de rongeurs du Pléistocene supérieur de la frotte de Caldeirão (Tomar, Portugal). Quaternaire 3(1):40–47

Purroy FJ, Varela JM (2005) Mamíferos de España. Península: Baleares y Canarias. Lynx Edicions. Barcelona

Quina AS, Bastos-Silveira C, Miñarro M, Ventura J, Jiménez R, Paulo OS, Mathias ML (2015) P53 gene discriminates two ecologically divergent sister species of pine voles. Heredity 115(5):444–451

Rabeder G (1981) Die Arvicoliden (Rodentia, Mammalia) aus dem Pliozän und dem alterem Pleistozän von Niederosterreich. Beitr Palaont Osterr 8:1–343

Rabeder G (1986) Herkunft und fruhe Evolution der Gattung Microtus (Arvicolidae, Rodentia). Z Saugetierkd (Mamm Biol):51:350–367