367

Radiol Bras. 2013 Nov/Dez;46(6):367–371

Preparation and management of complications in prostate

biopsies

*

Preparo e manejo de complicações em biópsias de próstata

Chiang Jeng Tyng1, Macello José Sampaio Maciel2, Bruno Lima Moreira2, João Paulo Kawaoka

Matushita Jr.2, Almir Galvão Vieira Bitencourt3, Miriam Rosalina Brites Poli4

Transrectal ultrasonography-guided biopsy plays a key role in prostate sampling for cancer detection. Among interventional procedures, it is one of the most frequent procedures performed by radiologists. Despite the safety and low morbidity of such procedure, possible complications should be promptly assessed and treated. The standardization of protocols and of preprocedural preparation is aimed at minimizing complications as well as expediting their management. The authors have made a literature review describing the possible complications related to transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biopsy, and discuss their management and guidance to reduce the incidence of such complications.

Keywords: Prostate; Needle biopsy; Interventional ultrasonography; Complications.

A biópsia transretal da próstata guiada por ultrassonografia tem papel fundamental na coleta de amostra para o diagnóstico do câncer prostático. Dentro do contexto intervencionista, constitui um dos principais procedimentos rea-lizados pelo radiologista. Embora seja segura e com baixa morbimortalidade, complicações devem ser prontamente avaliadas e tratadas. O uso da padronização das condutas e do preparo antes do procedimento tem a finalidade de minimizar as complicações, assim como agilizar o seu tratamento. Dessa forma, o objetivo deste trabalho foi fazer uma revisão da literatura sobre as complicações relacionadas à biópsia transretal de próstata guiada por ultrassonografia, discutir seu manejo e orientações para reduzir sua incidência.

Unitermos: Próstata; Biópsia por agulha; Ultrassonografia de intervenção; Complicações.

Abstract

Resumo

* Study developed at A.C. Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

1. Master, Titular in Charge of the Sector of Intervention, Imaging Department, A.C. Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

2. MDs, Residents, Imaging Department, A.C. Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

3. PhD, Chairperson of the Imaging Department, A.C. Ca-margo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

4. MD, Titular in Charge of the Sector of Ultrasonography, Imaging Department, A.C. Camargo Cancer Center, São Paulo, SP, Brazil.

Mailing Address: Dr. Chiang Jeng Tyng. A. C. Camargo Can-cer Center. Rua Professor Antônio Prudente, 211, Liberdade. São Paulo, SP, Brazil, 01509-010. E-mail: chiangjengtyng@gmail. com.

Received April 13, 2013. Accepted after revision June 7, 2013.

Tyng CJ, Maciel MJS, Moreira BL, Matushita Jr JPK, Bitencourt AGV, Poli MRB. Preparation and management of complications in pros-tate biopsies. Radiol Bras. 2013 Nov/Dez;46(6):367–371.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

Preprocedural antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for all patients. This concept is based on the fact that 16% to 100% of cases of biopsy with no prophylaxis pre-sented either asymptomatic bacteriuria or transient bacteremia, increasing the risk for infectious complications such as urinary tract infection, sepsis and Fournier’s syn-drome(8). The antibiotic must have a

spec-trum for bacteria from the flora of the skin, rectum and genitourinary tract. Studies describe Escherichia coli as the main etio-logic agent of infections after biopsies, but Streptococcus faecalis and bacterioid or-ganisms are also frequently reported. The utilization of broad spectrum antibiotics is a common practice, but guidelines should be locally developed according to the mi-crobiological profile, taking the regional antibiotic resistance into consideration.

In a meta-analysis, Zani et al. have dem-onstrated that preprocedural antibiotic pro-phylaxis reduces significantly the risk for bacteriuria, bacteremia, fever, urinary tract infection and hospitalization(9). No

signifi-and results have already been widely stud-ied(4,5).

Such procedure is relatively simple, rapid and safe, with low morbimortality. Generally, the complications are mild, but some precautions should be taken in the patients’ preparation in order to avoid more severe complications. Despite the already published guidelines(6,7), there is a lack of

standardization of such procedure in Bra-zil, so different types of preparation are adopted by the different institutions.

The present study aimed to review the literature on complications related to trans-rectal US-guided prostate biopsy, discuss its management and directions to reduce its incidence.

PREPROCEDURAL ORIENTATIONS

Every patient undergoing such proce-dure must be previously instructed and in-formed about risks and possible complica-tions. The patients’ preparation for trans-rectal US-guided prostate biopsy is still a controversial issue.

INTRODUCTION

Recent studies published in Brazil have highlighted the relevance of interventional radiology to collect appropriate material for the diagnosis of several diseases in dif-ferent organs(1–3). In this context,

cant difference was observed between the administration pathways, whether oral or systemic.

Currently, quinolones (ciprofloxacin, for example) are the antibiotics of choice, since oral administration allows a good absorp-tion, reaching good levels in prostatic tis-sue(10–12). Still there is a lack of consensus

about the regimen duration. Several stud-ies have compared a single-dose regimen with a three-dose regimen (one dose 30 to 60 minutes before the procedure and con-tinuation for the two following days). Evi-dences suggest that a single dose is as effec-tive as the prophylaxis with multiple anti-biotic doses(13–15). Considering all the

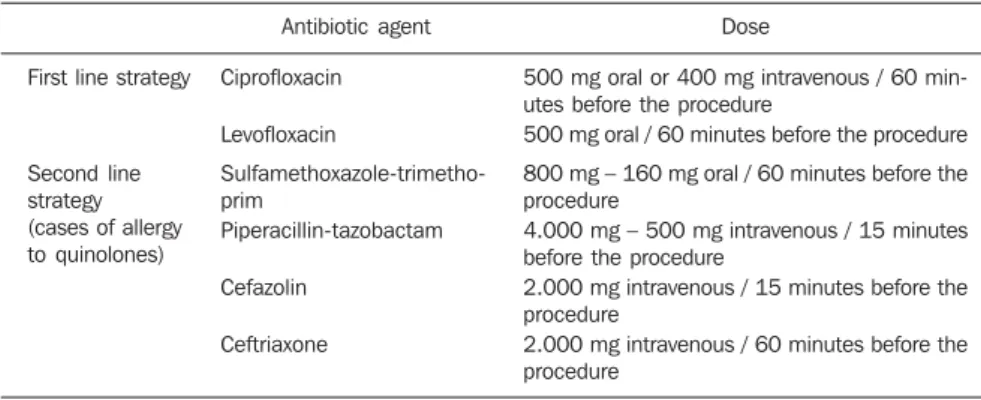

evi-dences described in the literature, availabil-ity, convenience e cost, the authors recom-mend antibiotic prophylaxis with oral 500 mg ciprofloxacin taken one hour before bi-opsy. In patients with major risk factors, such as diabetes, immunodepression, recent use of corticoids, severe urinary dysfunction or prostate volume > 75 g, antibiotic therapy may be maintained for three days, in spite of the lack of evidences in the literature justifying such strategy. In patients with history of allergy to quinolones, sulfame-thoxazole-trimethoprim, piperacillin-tazo-bactam, cefalosporines or aminoglycosides may be utilized. Table 1 describes the rec-ommended doses of antibiotic therapy.

The wide utilization of quinolones has increased the rate of infections by resistant strains of E.coli. The additional utilization of intravenous aminoglycoside reduces the risk of such infection in institutions where this problem has been documented(16,17).

Patients under risk for development of en-docarditis or infection of prosthetic heart valves, cardiac pacemakers or implanted cardiac defibrillators, benefit from the

as-sociated use of intravenous ampicillin and gentamicin before the procedure, followed by oral quinolone for 2–3 days.

Bowel preparation

Bowel preparation before transrectal biopsy of prostate, either by means of en-ema, suppository or povidone lavage, is based on the assumption that such prepa-ration would reduce the incidence of infec-tious complications by bacteria present in the rectal ampulla. Considering the fact that the rectum contains feces only during defecation, the routine utilization of pre-biopsy bowel preparation is questionable. Some authors believe that such preparation might even increase the level of bacteria in the rectum since it liquidizes the feces in the sigmoid colon and also impairs the quality of the sonographic images because of the air inserted during the prepara-tion(18).

Evidences demonstrate that there are no significant difference in the rates of infec-tious complications among patients submit-ted or not to bowel preparation, since they have undergone antibiotic prophy-laxis(18,19). Thus, some authors support that

bowel preparation increases the cost of the procedure and the discomfort of the patient with no additional benefit. For this reason, patients submitted to appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis do not require pre-biopsy bowel preparation.

Anticoagulant and antiplatelet agents

Many of the patients submitted to pros-tate biopsy present with increased cardio-vascular risk and continuously use antico-agulant agents or antiplatelet therapy. The decision about discontinuing or continuing such therapies should be made in

conjunc-tion with the assisting physicians, taking the risks for bleeding and cardiovascular events into consideration.

Although prospective studies with pa-tients under continuous use of low doses of acetylsalicylic acid (AAS) submitted to transrectal prostate biopsy have not dem-onstrated any increase in the incidence of severe hemorrhagic complications(20,21),

most urologists recommend discontinua-tion of the therapy. AAS and other nonste-roidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be discontinued three to five days before the biopsy, while clopidogrel should be discon-tinued seven days before, and ticlopidine, 14 days before the procedure(22,23).

As regards the use of anticoagulant therapy with coumarins, the lack of evi-dences about post-biopsy hemorrhagic complications in such patients suggests that such therapy should be discontinued four to five days before the procedure(24,25).

Fur-ther studies are necessary to change such practice and establish some recommenda-tions according to the risk for thrombosis and indication for anticoagulation(26).

Pa-tients with history of acute venous or arte-rial thromboembolism in the last month preceding the biopsy should undergo the procedure as an inpatient, and with the anticoagulant therapy replaced by intrave-nous heparin. In cases of patients with other indications for anticoagulant therapy (for example, metal heart valves, recurrent venous thromboembolism or atrial fibrilla-tion) and lower risk for embolic events, the therapy may be changed to subcutaneous or low-molecular-weight heparin.

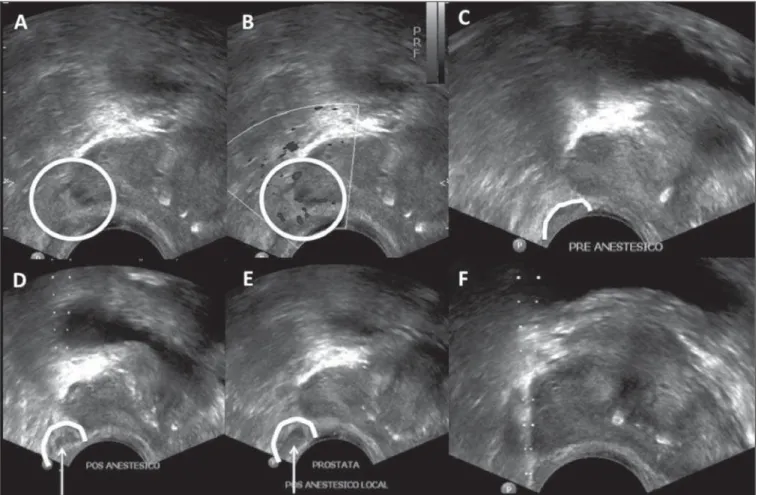

Anesthesia

Although transrectal prostate biopsy is generally well tolerated without the use of anesthesia(27), the pain and anxiety related

to the procedure may lead to unfavorable outcomes besides influencing the decision of the patient about undergoing a new bi-opsy. Randomized studies have demon-strated that the use of topic anesthetics alone does not reduce the pain(28–30). Thus,

local anesthesia or sedation should be rou-tinely performed in order to reduce the patient’s discomfort during the procedure, particularly in younger patients and during procedures requiring the collection of a greater number of specimens.

Table 1 Antibiotic prophylaxis and recommended doses.

First line strategy

Second line strategy (cases of allergy to quinolones)

Antibiotic agent

Ciprofloxacin

Levofloxacin

Sulfamethoxazole-trimetho-prim

Piperacillin-tazobactam

Cefazolin

Ceftriaxone

Dose

500 mg oral or 400 mg intravenous / 60 min-utes before the procedure

500 mg oral / 60 minutes before the procedure

800 mg – 160 mg oral / 60 minutes before the procedure

4.000 mg – 500 mg intravenous / 15 minutes before the procedure

2.000 mg intravenous / 15 minutes before the procedure

Sedation with a hypnotic agent (for ex-ample, midazolam or propofol) is generally performed by an anesthetist. Such tech-nique promotes great satisfaction and is widely accepted by patients for reducing the discomfort secondary to the transducer positioning and the patient’s fear in relation to the procedure, providing a calm environ-ment for its performance(31,32). However, an

anesthetic agent should be associated to prevent postoperative pain; fentanyl is the most utilized in such cases. But such asso-ciation is not free from risks, as cases of respiratory depression may occur due to the interaction between fentanyl and propo-fol(31). It is important that patients that are

candidates to biopsy with sedation undergo a preanesthetic assessment to determine the surgical risk and for a better anesthetic planning. The patient must be appropriately monitored during the procedure which should be preferentially performed in a hospital environment.

In cases where sedation is not per-formed, local anesthesia with periprostatic nerve block is highly recommended. Sev-eral techniques have been described; among them the most accepted one is the injection of 5 ml of 2% lidocaine using a 7 in / 22 gauge spinal needle into the peripro-static nerve pathway, at the junction be-tween the seminal vesicles and the base of the prostate, bilaterally (Figure 1). Evi-dences demonstrate that such a technique allows for a satisfactory management of the pain, without increasing the incidence of complications(32–35).

Systemic arterial hypertension

No evidence is found in the literature to indicate an increase in the risk for compli-cations after transrectal prostate biopsy in patients with high arterial pressure levels during the procedure. But, theoretically, there is an increased risk for bleeding in such cases. Additionally, the presence of

arterial hypertension increases the risk for cardiovascular events during surgical pro-cedures. Special care should be taken with patients undergoing procedures under se-dation, considering that anesthetics may increase the systemic arterial pressure and the cardiac frequency(36,37).

In general, such procedure should be avoided in patients with systolic pressure > 170 mmHg or diastolic pressure > 110 mmHg. Patients under chronic use of anti-hypertensive drugs should maintain their regular medication, even in the day of the procedure. The reduction of blood pressure levels could be achieved with either oral or parenteral administration of antihyperten-sive drugs.

POSTPROCEDURAL ORIENTATIONS

The patients should be advised about rest, liquids ingestion, antibiotic prophy-laxis and post-biopsy follow-up. At any

patient discharge after transrectal US-guided prostate biopsy, one must be sure that he has understood the potential com-plications from the procedure, requiring medical assistance in case of fever or other signs of infection, urinary obstruction/re-tention or persistent bleeding. Patients with urethral catheter or diabetes mellitus re-quire a more strict monitoring in relation to signs of sepsis.

COMPLICATIONS

Transrectal US-guided prostate biopsy is generally a well tolerated procedure with no complication. The rates of discomfort and major complications do not depend on the number and site of punctures made with the biopsy needle and their incidence is not higher in patients submitted to an initial biopsy or rebiopsy after some weeks(38,39).

Minor complications

A small urinary and/or rectal bleeding is expected after prostate biopsy, but is gen-erally self-limited and does not require any intervention. Hematospermia is the most frequent complaint from patients (6.5% to 74.4% of cases), followed by hematuria (up to 14.5% of cases) and rectal bleeding (2.2% of cases). Such complications may persist for up to two weeks, with a progres-sive decrease in their intensity(40,41).

Major complications

The rate of severe complications related to transrectal US-guided prostate biopsy is low. Infection, hemorrhage and urinary ob-struction are the most common severe com-plications from such procedure. Hospitaliza-tion is required in up to 1.6% of patients(42).

Infections related to the procedure or febrile episodes are reported in up to 6.6% of cases, with urosepsis caused by aerobic bacteria in 0.3% of cases(42). In the

litera-ture, septicemia caused by anaerobic organ-isms is reported with low frequency. Prebiopsy antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the rate of urinary tract infection, but some patients are at risk for severe infectious complications independent of the prophy-laxis. The main risk factors that are predic-tive for sepsis include the presence of ure-thral catheter and diabetes mellitus(43,44).

The treatment of urinary infection related

to prostate biopsy with oral antibiotics (such as quinolones and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim) is generally sufficient, al-though hospitalization and intravenous antibiotic therapy may be necessary(42,45).

Antimicrobial treatment may be altered on the basis of the clinical response and the results of uroculture and antibiogram. Acute bacterial prostatitis is relatively uncommon and is characterized by perineal pain, fever, chills, irritative micturition symptoms (mic-turition urgency, polacyuria and dysuria) and even acute urinary retention. Such complication must be promptly assessed and treated otherwise there is a risk for pro-gressing to sepsis, development of prostatic abscess and dissemination to adjacent or-gans such as epididymis and testis(46).

Urinary obstruction/retention (including obstruction by clot or secondary to the lo-cal postbiopsy inflammatory alterations themselves) is described in 0% to 4.6% of cases(42). The assessment of post

micturi-tion residue must be made in symptomatic patients. Therapy with alpha-adrenergic blockers may be initiated in patients with residual urinary volume < 100 ml, while insertion of a low-caliber urethral catheter or cytostomy may be necessary in patients with greater residual volumes.

Severe rectal bleeding requiring inter-vention is a rare complication, occurring in up to 1% of cases(47). The management of

patients with significant hemorrhage at the moment of biopsy is described in the algo-rithm below. In hemodynamically stable

patients with active rectal bleeding, manual (digital) compression of the prostate (or compression with the sonographic trans-ducer) is the primary strategy line. A set of gauzes applied to the rectum may be uti-lized(48). As direct pressure is applied over

the prostate, the vital signs of the patient are monitored and the coagulation parameters are verified and corrected as necessary. The rectal insertion of a Foley catheter with an inflated (50 ml) balloon has shown to re-duce hemorrhage(49); but the routine use of

such technique to prevent bleeding is not supported, since it causes unnecessary dis-comfort for a borderline benefit. Neverthe-less, such technique may be used for tem-porary management of the bleeding until a resolutive intervention is performed. In case the bleeding remains active or the pa-tient is hemodynamically unstable, an en-doscopic intervention (for epinephrine in-jection or clipping) or surgery (for example, ligature) should be performed(47,50).

Any patient with a major complication related to the procedure should be assessed and followed-up by an experienced urolo-gist.

CONCLUSIONS

Radiologists involved in the perfor-mance of transrectal US-guided prostate biopsy should know the complications re-lated to the procedure as well as their man-agement. The guidance on preprocedural preparation is fundamental to reduce the

Algorithm for management of active rectal bleeding following prostate biopsy. persistent bleeding

refractory bleeding or hemodynamically unstable patient

Active rectal bleeding

Manual (digital) compression or compression with the US transducer (a set of gauzes may be

Insertion of a Foley catheter (50 mL) for temporary management until an endoscopic or surgical procedure is performed

Endoscopic intervention (for epinephrine injection or Endo Clip™) or surgical intervention (ie, ligature)

➤

➤

incidence of severe complications. In such a context, antibiotic prophylaxis should be routinely performed.

REFERENCES

1. Chojniak R, Pinto PNV, Tyng CJ, et al. Computed tomography-guided transthoracic needle biopsy of pulmonary nodules. Radiol Bras. 2011;44:315– 20.

2. Chojniak R, Grigio HR, Bitencourt AGV, et al. Percutaneous computed tomography-guided core needle biopsy of soft tissue tumors: results and correlation with surgical specimen analysis. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:259–62.

3. Ceratti S, Giannini P, Souza RAS, et al. Ultra-sound-guided fine-needle aspiration of thyroid nodules: assessment of the ideal number of punc-tures. Radiol Bras. 2012;45:145–8.

4. Scherr DS, Eastham J, Ohori M, et al. Prostate bi-opsy techniques and indications: when, where, and how? Semin Urol Oncol. 2002;20:18–31. 5. Smeenge M, de la Rosette JJ, Wijkstra H. Current

status of transrectal ultrasound techniques in pros-tate cancer. Curr Opin Urol. 2012;22:297–302. 6. Dall’Oglio MF, Crippa A, Faria EF, et al.

Diretri-zes de câncer de próstata. Rio de Janeiro: Socie-dade Brasileira de Urologia; 2011.

7. Rocha LCA, Silva EA, Costa RP, et al. Biópsia de próstata – projeto diretrizes. Sociedade Brasi-leira de Urologia. Rio de Janeiro: Associação Médica Brasileira e Conselho Federal de Medi-cina; 2006.

8. Puig J, Darnell A, Bermúdez P, et al. Transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy: is antibiotic prophylaxis necessary? Eur Radiol. 2006;16:939– 43.

9. Zani EL, Clark OA, Rodrigues Netto N Jr. Anti-biotic prophylaxis for transrectal prostate biopsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(5):CD006576. 10. Aron M, Rajeev TP, Gupta NP. Antibiotic prophy-laxis for transrectal needle biopsy of the prostate: a randomized controlled study. BJU Int. 2000; 85:682–5.

11. Muñoz Vélez D, Vicens Vicens A, Ozonas Mora-gues M. Antibiotic prophylaxis in transrectal prostate biopsy. Actas Urol Esp. 2009;33:853–9. 12. Bootsma AM, Laguna Pes MP, Geerlings SE, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis in urologic procedures: a systematic review. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1270–86. 13. Lindstedt S, Lindström U, Ljunggren E, et al. Single-dose antibiotic prophylaxis in core pros-tate biopsy: impact of timing and identification of risk factors. Eur Urol. 2006;50:832–7. 14. Shigemura K, Tanaka K, Yasuda M, et al. Efficacy

of 1-day prophylaxis medication with fluoroqui-nolone for prostate biopsy. World J Urol. 2005; 23:356–60.

15. Shandera KC, Thibault GP, Deshon GE Jr. Effi-cacy of one dose fluoroquinolone before prostate biopsy. Urology. 1998;52:641–3.

16. Hori S, Sengupta A, Joannides A, et al. Chang-ing antibiotic prophylaxis for transrectal ultra-sound-guided prostate biopsies: are we putting our patients at risk? BJU Int. 2010;106:1298–302. 17. Steensels D, Slabbaert K, De Wever L, et al. Fluoroquinolone-resistant E. coli in intestinal flora of patients undergoing transrectal

ultra-sound-guided prostate biopsy – should we reas-sess our practices for antibiotic prophylaxis? Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:575–81.

18. Zaytoun OM, Anil T, Moussa AS, et al. Morbid-ity of prostate biopsy after simplified versus com-plex preparation protocols: assessment of risk fac-tors. Urology. 2011;77:910–4.

19. Carey JM, Korman HJ. Transrectal ultrasound guided biopsy of the prostate. Do enemas de-crease clinically significant complications? J Urol. 2001;166:82–5.

20. Giannarini G, Mogorovich A, Valent F, et al. Con-tinuing or disconCon-tinuing low-dose aspirin before transrectal prostate biopsy: results of a prospec-tive randomized trial. Urology. 2007;70:501–5. 21. Maan Z, Cutting CW, Patel U, et al. Morbidity of

transrectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biop-sies in patients after the continued use of low-dose aspirin. BJU Int. 2003;91:798–800.

22. Mukerji G, Munasinghe I, Raza A. A survey of the peri-operative management of urological patients on clopidogrel. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009; 91:313–20.

23. El-Hakim A, Moussa S. CUA guidelines on pros-tate biopsy methodology. Can Urol Assoc J. 2010;4:89–94.

24. Ihezue CU, Smart J, Dewbury KC, et al. Biopsy of the prostate guided by transrectal ultrasound: relation between warfarin use and incidence of bleeding complications. Clin Radiol. 2005;60: 459–63.

25. Ghani KR, Rockall AG, Nargund VH, et al. Pros-tate biopsy: to stop anticoagulation or not? BJU Int. 2006;97:224–5.

26. Kearon C, Hirsh J. Management of anticoagula-tion before and after elective surgery. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:1506–11.

27. Irani J, Fournier F, Bon D, et al. Patient tolerance of transrectal ultrasound-guided biopsy of the prostate. Br J Urol. 1997;79:608–10. 28. Yurdakul T, Taspinar B, Kilic O, et al. Topical and

long-acting local anesthetic for prostate biopsy: a prospective randomized placebo-controlled study. Urol Int. 2009;83:151–4.

29. Szlauer R, Gotschl R, Gnad A, et al. Comparison of lidocaine suppositories and periprostatic nerve block during transrectal prostate biopsy. Urol Int. 2008;80:253–6.

30. Song SH, Kim JK, Song K, et al. Effectiveness of local anaesthesia techniques in patients undergo-ing transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy: a prospective randomized study. Int J Urol. 2006;13:707–10.

31. Barbosa RAG, Silva CD, Torniziello MYT, et al. Estudo comparativo entre três técnicas de anes-tesia geral para biópsia de próstata dirigida por ultrassonografia transretal. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2010;60:457–65.

32. Song JH, Doo SW, Yang WJ, et al. Value and safety of midazolam anesthesia during transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Korean J Urol. 2011;52:216–20.

33. Bingqian L, Peihuan L, Yudong W, et al. Intra-prostatic local anesthesia with periIntra-prostatic nerve block for transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2009;182:479–83.

34. Ashley RA, Inman BA, Routh JC, et al. Prevent-ing pain durPrevent-ing office biopsy of the prostate: a

single center, prospective, double-blind, 3-arm, parallel group, randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2007;110:1708–14.

35. Kuppusamy S, Faizal N, Quek KF, et al. The effi-cacy of periprostatic local anaesthetic infiltration in transrectal ultrasound biopsy of prostate: a pro-spective randomised control study. World J Urol. 2010;28:673–6.

36. Wolfsthal SD. Is blood pressure control necessary before surgery? Med Clin North Am. 1993;77: 349–63.

37. Eagle KA, Berger PB, Calkins H, et al. ACC/AHA guideline update for perioperative cardiovascular evaluation for noncardiac surgery – executive summary a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Up-date the 1996 Guidelines on Perioperative Car-diovascular Evaluation for Noncardiac Surgery). Circulation. 2002;105:1257–67.

38. Rodríguez LV, Terris MK. Risks and complica-tions of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsy: a prospective study and review of the literature. J Urol. 1998;160:2115–20. 39. Djavan B, Waldert M, Zlotta A, et al. Safety and

morbidity of first and repeat transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsies: results of a pro-spective European prostate cancer detection study. J Urol. 2001;166:856–60.

40. Ecke TH, Gunia S, Bartel P, et al. Complications and risk factors of transrectal ultrasound guided needle biopsies of the prostate evaluated by ques-tionnaire. Urol Oncol. 2008;26:474–8. 41. Loeb S, Carter HB, Berndt SI, et al. Complications

after prostate biopsy: data from SEER-Medicare. J Urol. 2011;186:1830–4.

42. Chiang IN, Chang SJ, Pu YS, et al. Major com-plications and associated risk factors of transrectal ultrasound guided prostate needle biopsy: a ret-rospective study of 1875 cases in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc. 2007;106:929–34. 43. Simsir A, Kismali E, Mammadov R, et al. Is it

possible to predict sepsis, the most serious com-plication in prostate biopsy? Urol Int. 2010;84: 395–9.

44. Lange D, Zappavigna C, Hamidizadeh R, et al. Bacterial sepsis after prostate biopsy – a new perspective. Urology. 2009;74:1200–5. 45. Lindert KA, Kabalin JN, Terris MK. Bacteremia

and bacteriuria after transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy. J Urol. 2000;164:76–80. 46. Sharp VJ, Takacs EB, Powell CR. Prostatitis:

di-agnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2010; 82:397–406.

47. Brullet E, Guevara MC, Campo R, et al. Massive rectal bleeding following transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. Endoscopy. 2000;32:792– 5.

48. Maatman TJ, Bigham D, Stirling B. Simplified management of post-prostate biopsy rectal bleed-ing. Urology. 2002;60:508.

49. Kilciler M, Erdemir F, Demir E, et al. The effect of rectal Foley catheterization on rectal bleeding rates after transrectal ultrasound-guided prostate biopsy. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:1344–6. 50. Braun KP, May M, Helke C, et al. Endoscopic