·.

" I;

•

Fundação Getulio Vargas

E

p

G

E

Escola de Pós-Graduação em Economia

Seminários de Pesquisa Econômica 11

(2ª

parte)

J

Steve De Castro

(UNb)

~~DEBA.NiD~8EDm

aESESTA.NiCE

TO,

caE.&,TEVE DmSTaUCTEON E.

SCHUBPETEaEA,Ni GaOWTB

THmO~Ttt

LOCAL:

DATA:

HORÁRIO:

Fundação Getulio Vargas

Praia de Botafogo, 190 - 10° andar

Sala 1021

20'l0/94 (quinta-feira)

15:30h

'marf.

Coordenação: Prof Pedro Cayalcanti Ferreira

I,Tel: .536-\)3.5~

F

.,

-

1

· .-

~

',l

DEMAND-SIDE RESIST ANCE TO CREA TIVE DESTRUCTION IN SCHUMPETERIAN GROWTH THEORY

by Steve De Castro' Departamento de Economia Universidade de Brasilia August 1993 Abstract

The Schumpelerian model of endogeno~s growlh is generalized with lhe introduction of

stochastic resislance. by agenls other Ihan producers. to lhe innovations which drive growth. This causes a queue to be formcd of innovations, alrcady discovered, bUI

waiting to be adopled~ A slationary stochastic equilibrium (SSE) is obtained when the

queue is stable~ It is shown that in the SSE, such resistance will always reduce lhe

average growth iate hut it may increa~e wclfare in certain silualions. In an example, Ihis

is when innovatiuns are small anti monopoly power great. The cont1icl hetween this welfare motive for resistance and those of rent-seeking innovalors.may well explain why growth rates differ.

Keywords: cnJugenous growth, Schumpeterian, demand-side resistance, qucue

• I am graleful 10 CNPq, lhe Brazilian !'Ialional Rescareh Council. fur a fellowship in 1992-3 and 10 CEME, Frce Universily uf Brusse!> (ULB) for Ils hospilalily and slimulus, for rcse3fch~

I

#

Introduétion

In 1870, Ireland, Spain, Portugal, Chile and Argentina were among the twenty richest countries. In 1830,60% of industrial production was in the third world. By 1900, the share was 1I % (Bairoch (1982». lt is implausible that such dramatic variations in long-run performance can be explained by production-side frictions alone. In this paper, we show how wider resistance to technological change, by agents other than producers, may increase welfare by reducing the social inefficiency of the imperfect competition required to reward the innovations which cause growth. The social tension between this welfare motive for resistance, which is shown here always to reduce growlh, and those

ofrent-seeking innovators, may well be the source of what makes growth rates differ.

We generalize the stochastic framework developed by Aghion and Howitt (1992), and Grossman and Helpman (1991, Chapter 4, 1991a), by inlroducing demand-side resistance to innovations. There, better lechniques for producing one or more intermediates are created at random intervals in a Poisson process, by competitive research activities, and gain immediale .adoplion by a sequence of monopolies in each intermediate. Old and new lechniques cannol coexist in use age. This is the result of a Ídnd of strategic behaviour by each new monopolist which we will question at the end. For simplicity and as in most of Aghion and Howitt, we have a single inlermediate.

Innovations now are not available for adoption until they pass an evaluation which consumes only time, and which is separate from the interaction between research firms and the monopolist. The procedure is modelled here as a simple queue, formed of

innovations not yet liberated for adoption. The mean service rate of lhe queue can be

unambiguously idenlified as coming from oUlside the research and produclion spheres and acts to retard the flow of innovations through the economy.

The characleristics of a single server queue with Poisson arrivals and exponential service time. are mobilized lo describe and analyse a stationary stochastic equilibrium (SSE) in the Aghion and Howitt model. Since the arrival process for innovations is identical. the queue is a generalization when it is formed by innovalions wailing lo be adopted.

Early recent auempts to make endogenous lhe technical progress necessary to sustain growth within lhe neoclassical paradigm (Romer ( 1986), Lucas ( 1988» stress the argumenl thal for R&D activily to be inlenlional. it musl be rewardcd. From Eulcr's

392

lO . '

theorem: if the two factors in Solow's aggregate production function receive their marginal products. there would be nothing lef! over for rewarding R&D. Preserving the paradigm requires some form of irI)perfect competition.

The models we study here abandon the notion of an aggregate production function. They use Schumpeler's ide a that new techniques also deslroy the rents captured by old ones, the creative destruclion he thought was central to capitalismo Despite the obsolescence they cause, the innovations can sustain growth under certain assumptions, even without the accumulation of physical capital. This fealure ought to be especially attractive to old-Cambridge types and even to one or two Oxford chaps (Seou (1989), for example). There is nevertheless, implicit saving and inveslment behaviour behind the financing of research.

The microeconomics of the production side carne from the partial equilibrium contexl of lhe palenl race lileralure (see Tirole (1988), Chapler 10). lnnovating agents seek renls in Iheir own sectors, but for growlh Iheory. feedbacks are added to get intertemporal general equilibrium. For example, more output in other sectors increase the cost of research Ihrough competition for.skilled labour; also lhe expeclation of increased future research reduces currenl research because of its reduced expecled rents due to possible earlier obsolescence ofits innovations.

Some recent related work by Romei (1990), and Grossman and Helpman (1991, Chapler 3), also make the R&D activity explicil. However. lhe innovations create entirely new produclS (varicly) ralher Ihan as here, improved versions of old ones (quality). The elemenl of obsolescence or crealive destruclion is missing in these because lhe new products arrive to sit si de by side (horizonlally) with existing ones, in lhe produclion or utilily funclions they enter.

We use llie Aghion and Howiu (1992) framework and notalion Ihroughout and

refer lo il as A&H. The lechnical conlribution of our generalizalion is 10 show how

stochaslic lags belween innovalions and adoplions ean be treated there. The main economic result is Ihat in the SSE. demand-side resistance will always reduce lhe average growth rate, bul it will increase welfare in certain situalions. In A&I1's linear research, Cobb-Douglas example, Ihis is when innovalions are small and monopoly power grea!.

The spiril of demand-side resislance is captured in a suggestion by A&H (foolnote 4, p. 328) Ihat, inslead of innovations gaining complete adoption immedialely. each could be made to pass through a process of gradual diffusion in which its productivity

parameter (At) would follow a predelermined path asymtotically approaching lhe full design value. To lhe extenl lhat the gradual diffusion is not caused by the optimizing behaviour of firms. it can be interpreted as resistance from consumers. It may also have desireable welfare effects of lhe kind found here.

1.The queue of innovations

The innovations arrive in a Poisson processo from a competilive research seclor as in A&H. but now they must pass through a service mechanism before being made available to be bought by a new monopolist and used. in place of the previous

innovation. to produce a more efficient intermediate good. If there were no service

mechanism to delay the availabilily of lhe innovation. lhe mode) would be identical to A&H. Even if the arrival rate of innovations is much slower than the service rate. the service mechanism would stiU block the (arriving) successful innovation from immediate availability and adoption.

In lhe present version of our model then. the queue is formed of innovations t.

t = 1.2 ...• a1ready discovered but waiting for adoption during an interval TI(t) of time t

whose distribution would depend on the constant. exogenous. service parameter 11. as wel1 as the arrival parameter. Ã.$nl{t) at time t. As in A&H. the latter can vary with the number of skilled workers. nl(t). allocated to research. Innovations cannot jump the queue. even though they are superior - the queue discipline is first come. first served. The idea is that each innovation is examined and debated by Ihird parties in some separate processo before it passes to producers for adoplion. The slochaslic independence of lhe service mechanism f tOm the research and adoption sectors means we can use it to

represent consumer behaviour of some type. However until ÍI can be tied more explicilly

to preferences. it can also represent wider economic interests or even a govemment of this type.

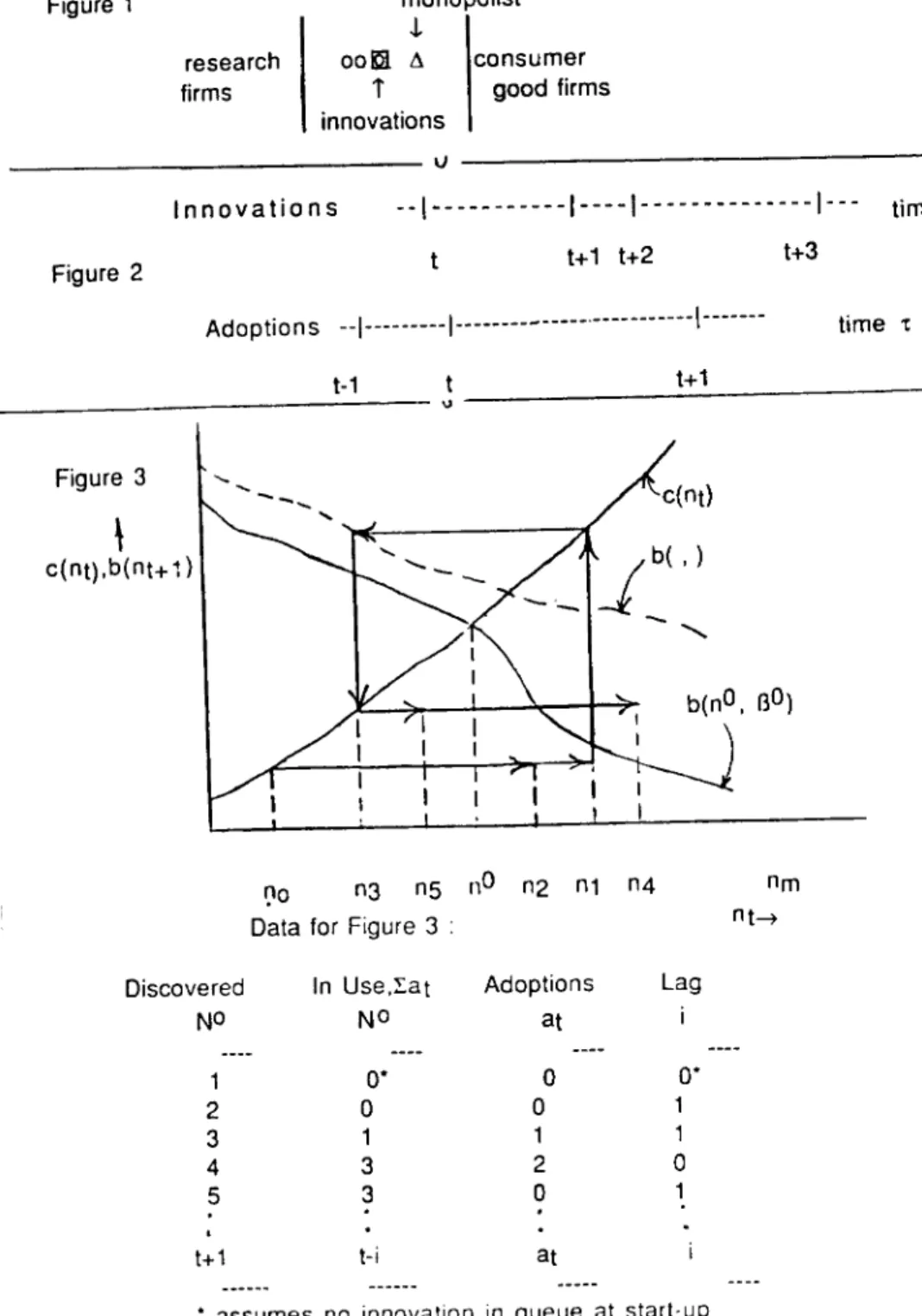

In figure I. we give a picture of lhe queue of innovations at a given instanl t. In

the figure there are 3 innovations waiting lo be adopted. including one in the service bay.

The triangle is lhe monopolist. the only supplier of lhe inlermediale The single consumer good is produced competitively with unskilled labour and the inlermediate and a constant retums production function.

[Figure 1 hereJ

394

,.

,,'

The characteristics of this queue are well worked out when mean arrival and service rates are constant. In particular. provided lhe arrival rate is less than the the service rate. the syslem reaches a statistical equilibrium defined as a limiting probability distribution Pj for the number of items j in the queue. This equilibrium is slationary because it has the property that if the number of items in the system aI any time t is given

according to the probabiJity distribution Pj • Ihen for any small interval dt > O. Pj is also

the probability Ihat j Ílems are in the syslem at time t+dt. The value of Pj can also be interpreled as the limiling fraction of an arbitrarily long period of lime during which lhe

queue conlains j items (see Wagner (1969). Chapler 20.5).

Although lhe mean arrival rate Ã.$nl{t) can vary over time. we will use lhe nOlion of a stationary stochastic equilibrium(SSE) to define Irajectories where the sequence of allocalions of skilled workers lo research. nl. is conslant. nO. For the economy lo reach

such an equilibrium. À${nO) must be less than

'.L

The probability distribution Pj. whichgives the statistical equilibrium for the queue of innovations. would contain al1 lhe analylical results we would need.

A&H used a slationary perfect foresighl equilibrium. defined to be an equilibrium in which agenls' expectalions are fulfilled and lhe skilled labour split belween research. nt. and inlermediale produclion. N-nt. is conslant over time. Even though both Ihese hypolheses are also mobilized for the SSE. we are reluclant lo use lhe same lerminology because lhe basic dynamic condition linking current and future allocations (nl. nl+I). is not fixed as in A&H. The stochastic delay between discovery and adoption intervenes and complicales lhe Iransienl Irajeclories. despile lhe common behavioural assumptions about rcsearch firins and lhe monopolist.

If analylical expressions can be oblained for lhe Iransient de\Jy dislributions. then

our dynamic condition cm. also be fixed. From qucuing lheory. il i~ possibJe lo oblain

Ihese dislribulions for lhe case of conslan! mean arrival and servi cc rales. Here lhe mean arrival rale is nOI only variable but would depend on lhe queuing lime. Even wilh lhe perfect foresight assumplion. obtaining lhe lransient distribulions wnuld be no mean feal.

Neilher money nor governmenl appears and lhe single consumer good is lhe numeraire lhroughoul.

The Iwo market equilibrium condilions in lhe research and intermediale good seclors are now derived. One is lhe free-enlry condilion for compelilive equilibrium for

r

research fmns. The other is lhe no-arbitrage condition for the value of an innovation lo a new inlerrnediale-good producer who under certain assumptions, is able immediately to drive the previous incumbenl from lhe market. These assumptions will be questioned in Section 3 below, l:iut for the moment we shall use them as in A&H, to maintain the sequence of monopolists. They also leave each monopolist with no incentive to do research himself.

Although the two condilions play the same role as in A&H, there are important differences introduced in both, by lhe fact that adoptions are not now immediale. To see this we can use figure 2 to follow each innovation t through time t lo evenlual adoplion.

[Figure 2 here}

In figure 2, we see lhal one or more adoplions of previollsly discovercd innovalions can occur during the interval of search for a new one. For examplc. ai lhe start of lh,e search for the (1+1)st innovation, the (1-1)st was in use. When lhe l-Ih is adopted during this search, lbis will change at once both lhe equilibrium wage rale and the allocation of skilled workers between research and interrnediate manufacluring.

However, the Poisson arrival process has lhe property which frees lhe decision as

to the levei of research lo conduct at any time 't, from dependence on whal went on before

t. For this, it is said to have no memory. It allows the specification of lhe profil maximization objeclive of each research firm as inslantaneous decisions taken ai every date t. t is omitted to Iighten lhe notation. Assuming that the (t-i)-th innovation is in use when the (t+ I )st is discovered, we would have in any small inlerval dt :

max Â.<ll(Zt_io St-i)dtvt+1 - Wt-iZt-idt - w:_iSt-idt

with respecl 10 Zt-i. St-i, where Zt-i, St-i, Wt-i. w:_i are the skilled and specialized labour

and their wage rates ai time t during the research for lhe (t+ I )st innovation. and

i = O, 1,2 .... is lhe lag belween the most recent innovation discovered and the one in

use. The no-memory property is used to specify the probability of discovery of the innovation during t and adt as Â.<ll(Zt-i, st-i)dt. It does not depend on the amount of research done before t.

One other change in this maximizalion wbich the queue.causes is in the value to an (outside) researeh firmo of lhe (1+l)st innovation, shown as vl+1 and not Vl+(' The two

396

,.

..

'are equal only if the innovation is adopt.:d immediately, as in A&H. Since there will usually be a delay Tt+1 between discovery and adoption, research firms wjl! discount the value Vt+1 paid by lhe monopolisl, if we assume Ihal the latter pays only when lhe innovation is released by the service mechanism. If he pays at discovery, then he would

wanl lO discount his future profits. In perfecI capital markels it comes to the same thing.

We assume lhe forroer and get:

(1.1) Vt+l = Vt+IPt+l

where Pt+1 '" Je-rTt+I f(Tt+l)dTt+1 is the delay discounl faclor.

The probabilily distribulion for the delay f(Tt+l) will vary wilh lhe Slale of lhe queue. Whal is more important here however is Ihal lhe dislribulion. like Vl+

I, does not

depend on lhe currenl decision variables of lhe research firms(zl_i, St-i). We oblain therefore a Kuhn- Tucker condilion for the industry qlúle e10se to thal of A&H:

(1.2)

Wt-i

~ Â.$'(nt-i)Vl+~PI+I,

nt-i~

O wilh ai leasl one equalitywhere $(nl-i) is defined lo be <ll(nt_i, R). R is lhe 10lal flow of specialized labour, fulIy employed in equilibrium, and only by lhe research seclor.

Even if there is never any innovalion waiting in lhe queue, A&H's condition would slilI be slighlly different, because lhe service mechanism would block immediate adoplion. This shows up in lhe slochastic delay discount factor PI+ I on lhe RHS of ( 1.2).

The second condition, no arbitrage, is derived from lhe value,V

I+1• to an outside

research firm, of an innovalion when il is sold lO a new monopolis\. The condilion relales the latter's expecled equity relurns lo lhe inleresl rale on a riskless bond paying rale r, wbich is also lhe discounl rale because lhe marginal ulility of consumplion is assumcd constan\. Equily c1aims pay dividends 1t1+ldt in a lime inlerval of lenglh dto Also wilhin this dt, a new innovalion may be released by lhe service mechanism of lhe queue with probability Jldt, in which case lhe exlant monopolist will forfeil ali of his income potentia! and suffer a capilalloss of size VI+I. The value VI+1 paid lo lhe research firm for the innovalion musl also be such Ihal the saroe inveslmenl in a riskJess bond at inlerest rale r, should yield lhe same relurn as equily invcsled in lhe monopoly. In the equalion, lhe dt is already cancclled oUI :

397

~

~

~

(1.3) Xt+\ -~Vt+1 = rVt+\ or Vt+\ = Xt+\/(r+~)

No\ice that the lag counter i does not appear in tbis eondition beeause the arrival of an innovation does not have any direet effeet on the intennediate monopoly. The queue of innovations blocks tbis.

For the same reason, the intennediate moncipol!st's price and quantity decisions

are identieal to that of A&H (see their Seetion 2.8). That is, the following funetions go

through:

CIlt

=

õ)(XI), oo'< O for XI > O, limxl-+o &=

00 , IimxI-+~ & = O(1.4)

XI = Alit( 011)' it > O and strictly deereasing for CIlt > O,

where 011 == wll AI is the produetivity-adjusted wage for skilled labour, and oo(x)

F(x) + xP'(x) is the marginal-revenue funetion, assumed to be downward-sloping and satisfying Inada-type conditions. F(x) is the reduced form of the production funetion for the consumption good Ylo when ali the fixed quantity M, of unskilled labour is employed,

giving YI = AIF(xt). When the intermediate good in use is the latest Xlo the productivlty

parameter AI is given by AI

=

Aoy..

Each innovation raises productivity by a fixed factory> 1.

All the other assumptions of A&H are valido Consumption good production is perfectly competi tive, and it uses only unskilled labour so that there is no feedback [rom it to the intermediate good monopolist Jhrough the labour market. The inlermediale is

produced using skilled labour alone with lhe linear lechnology XI = L, ~ N, where L, is

the input flow of skilled labour, and N is ils total availability, a constant.

2. The analysis of the stationary stochastic equilibrium (SSE)

2.1 Characterization ofthe SSE

Using the two equilibrium conditions (1.2) and (1.3), lhe expressions for lt, and

011 in (1.4), and the requirement of market c\earing for skilled labour (N

=

n, + x,), lhebasic condition is obtained for the allocalion over lime of the fixed 110w of skilled labour

398

(N) between research nl, and intennediate manufaelure, Xt, in the A&H eeonomy with demand-side resistanee to innovations:

(2.1)

õ)(N-nl-i)/Àcjl(n,_i)

~

1")'if(Õl(N-n,+,) /31+III(r+/1),nl-i ~ O, with alleasl one equality.

Condilion (2.1) relales the (skilled) researeh employment, nt-i, during the

~earch

for the (t+ 1 )st innovation, to the researeh employment during the use of lhe (t+ 1 )st

innovalion, nl+l· The fonner ineludes the lag eounter i. When i

=

O, the latest innovationis in use when lhe nexl is diseovered.

The two sides of lhe

ba.~ie

condition (2./) can be defined in a manner similar toA&H's, lo be c(n'_i) and b(nl+ I, /3,+ I), lhe marginal COSI and bcnefit of research respeclively. The extra slochaslic variable /3'+1 whieh appears in b(.) also depends, Iike

nl+\, on time T, because the distribution for the dclay Tt+1 betwcen discovery and

payment at adoption, is stable only in lhe SSE. Note also Ihat lhe denominalor of b(.), the risk-modified inleresl rale, now depends on lhe mean service rate /1, that is, on the rale of release and Iherefore the adoplion rale of innovations, and nOI as before, on Iheir arrival rale, Àcjl(n,+J}.

These differences would eause importanl modifications to A&H's figure. Now,

there would be a range of b(.)

curve~,

depending on lhe current probabilily distribulionfor the delay. This means Ihal a given value for n" read inlo lhe c(.) curve, can delermine more Ihan one valuc for n'+1 depending on lhe dale I . Aleach dale howcver, n, \ViII fix a singlc nl+l, oblained using lhe CUrrent dislribulion. A sceond modification is caused by the lag belween discovery and adoption. If no discovery OCcurs when an innovalion t is in use, Ihen n, \ViII delermine no fUlure levei of rcsearch.

[Figure 3 here J

Figure 3 was prepared using a specific numerical example, given in its accompanying lable, of a sequence of discoveries and adoptions. To simplify mallers, lhe example assumes Ihat no innovations were in lhe queue aI start-up. One of course, was in use, the O-th. Now, no fixes both nl and n2 because innovations 1 and 2 were discovered when the O-Ih was in use. However, n2 does not fix any fulure leveI beca use when 2 was in use, none was discovered.

~ CD

c:

~~

Z n

01> ;';> C"ls:

;r:.'l=-0 ; . ;r:.'l=-0 Ci)Õ!!l:c

~'~ 6::'11S

~c:::c

m ~tn;;2

i

To iIlustrate how the lag eounter i is ealculated, we note firstly that sinee no innovations were in the queue at start-up, i has zero initial value, Seeondly, when the seareh for the 4-th began, the 1st was still in use. But there were 2 adoptions during this

search, 50 that when lhe 4-lh was found, the 3rd was in use - lhe latest, and 50 i will be

zero.

The sequenee of researeh alloeations {ntl ~ that satisfies the basic e'ondition in

(2.1) as an equality, that is, when nt> O for ali t, will still be defined as one possible perfeet foresight equilibrium. However lhe allocations can follow a much more complex panem lhan A&H's counterclockwise spiral.

For every n such that À.cj)(n) < 11, say n < "m, the queue will eventually reach a

statistical equilibrium where the distribution for the delay time, Tt+I, would be stationary

and known - an exponential with parameter p(n)

=

11(1-À,cj)(n)/I1) (Wagner (1969, p.857».

The expression for lhe delay discount factor Pt+1 for Vt+l can then be obtained:

Pt+l = p(n}/(r+p(n)}

The positive value of n, nO, which satisfies the basic condition (2.1) will then be given by:

(2.2)

ro

(N-nO)/À,cj)'(nO)=

{yit(ii>(N-nO»/(r+I1)} {p(nO)/(r+p(nO»}, for nm > nO> O.For comparison with A&H, the stationary PFE value of

~

> O, for the systemwilhout demand-side resistance, is given by (see A&H's 3.3, p. 333):

ii>(N-~/À,cj)'(~) = yit(ii>(N-6»/(r+À.cj)(~).

Note that the RHS of (2.2) b(nO), comprises 2 factors, the second, containing penO), being the new delay discount factor which is always less than I. With similar arguments to A&H, one can.show that there is an unique nO> O which will yield aSSE. For example, if nO is allowed IOvary parametrically in (2.2), lhen c(n) and b(n) will have lhe same shapes as c(nt) and b(nt+l) there.

However, nt

=

't'(nHJ} would not now be stationary, and so the two-cyc1eequilibrium will beco me highly improbable.Nevertheless, a different kind of no-growth 400

r .'

trap may exist because the transient distribution for the delay Tt+1 and for the number of ador:ions i during search, may be such as to shut down research and hencç growth at any date, 1:.

2.2 8alanced growth in cite SSE

In the SSE, if one exists, the queue of innovations not yet adopted would be in

statistical equilibrium, with constant mean arrival and service rates, À.cj)(ri0 ) and 11

respectively. In this equilibrium, the distribution of the inter-arrival times of innovations wiCI be the same as the distribution of the use time of each: The time between each adoption (L'1I, L'12, ... ) would be a sequence of IID variables, exponentially distribllted

with parameter Àcj)(n

o).

Thus the ~Iochastic proct:s~ Jriving output in lhe SSE is iJcntical to Ihat of A&I1,

except for lhe value of nO. From lhe same argumcnts as in Ihcir section 3.C, it can be

shown that the discrete sequence of obs~rvations on the log of output follow5 a random

walk with constant positive drift. The economy's average growth rate(AGR) and its vanance(VGRl are given by:

(2.3) AGR = À4>(nO)lny, VGR = À<jl(nO)(lny )2

The AGR can bc eompared with A&H's through the value of nO. The service

pararneter 11 does not enter explicitly into the determination of the AGR; its intluence is

exprcssed through nO. If nO > (l, then our AGR will be unambiguously greater.

I1owC\cr, the cfkct on social welfan: of I1mllst aho be taken into account, and wc !Um to this next.

2.3 Soc;a!ll'd!are ;11 lhe SSE

If we makc the assurnption that the serviee lIlechanisrn does not rnakc any direct positivc contribution to social welfare, we must use lhe same rneasure as in A&H. That is, social wclfare should bc measured as if the innovations were adopted immediately, without demand-siJc resistance. The planner's objective is as before to maximize the

expcctcd prc,cnt valuc of consumption tlows y(1:J, given the innovation proccs~ is

Poisson with paramcter ÀQ(ntl. Since every innovalion raiscs y(1:) by the same factor, '(.

401

the optimal policy will again consist of a fixed levei of research, n. The planner choo~es n to maximise U:

u

=

Je-rt~p(t,t)AIF(N-n)dt

°

(Ã.4!(n )t)te-À$(n)t

where P(.) == t! is the probability that there will be exactly t atloptions up

to time t.

The socially optimallevel of research n* which maximizes'U will be given by the sarne first-order eondition for an interior maximum as in A&H's equation 4.4:

F(N-n*) À$'(n*)

(y-I )F(N-n*) r-À$(n*)(y-I)

Once again, the qllestion tums on whelher or not nO < n* Additionally, there is

interest in whether or nol nO> {)- for ~ > O.

Since we have the adtlitional parameter ~ to play with, we can also ask whelher

there will always exist an optimal value of~, ~ *, which can make the value of nO eqllal

n*. That is with ~ *, if it exists, the laissez-fàire sollltion will also bc welfare maximizing

in the SSE.

Now it was shown by A&II (Seclion 4) thal

tJ

can he greater or less lhan n',meaning that lhe laisscz·faire AliR Illay bc more or Icss lhan lhe optimal :\(iR. In lheir linear research, Cobb-Douglas example, where the appropriabilily anti

Illonopoly-distortion effects are eombined in the factor (I-a) in lhe equation (3.4) tlelermining

fl.

these together lentl to make the laisscz-faire AGR less lhan oplimal. 1I0wc\'cr, whcn

there is mueh monopoly power ( a dose to zero) anti innovations are small (y close lO I).

the business-stcaling dfects dominale, and

tJ>

n* anti lhe laissez-f.lirc AGR is gn:atcrthan the optimal.

2.4 SociallVelfare and growlh in lhe SSE

The tir,l irnportanl result in this ~cclion is thal any posilive dcmand-sidc rcsi,lancc

will always bc wnrsc for growlh. Thal is, nO < fl for ali Jl > O. Onc consl"Llllcnce is Ih<11

402

,

.'

reslstanee will only improve welfare when fl> n *. On the other hand, when

fl

< n *, anypo~itive resistanee will be worse for both welfare and growth. A&H's linear

Cobb-Douglas example allows an eeonomie interpretation. There, fl < n* was the case where

large size of innovations (y» I), coineided with little monopoly power (a dose to I).

The second important finding is that the mean service rate ~ has two opposing

comparative-statics effects on nO, the SSE researeh allocation. We cannot yet decide which will dominate. However, no matter which dominates, there will be cases where, in the presence of demand-side resistance, it may be possible to increase welfare by shifting

~. If ~ increases na and nO < n*, then increasing ~ will increase both welfare and

growth; similarly, if ~ decreases nO and nO > n *, again we can get the two pay-offs. For

the other cases, one may get either growth or welfare or neither.

To show lhat nO <

fl

for ali Jl > O, we compare the two terms in b(n) whichmultiply the one common to both modcls, yit(ÕJ(N-n». Since c(n) is itlentieal in both, the larger term will give a bigger solution value for n. The term in A&H is larger, narnely:

1 I p(n)

>

-(r+À$(n» (r+~) (r+p(n))

because ~ > Àq,(n) in the SSE, and the oelay discount factor is always less than \.

The compurati\"e-slatics effeets of ~ on nO, will depend on how it shifts the b(n)

function, sinee ~ does not appear in c(n). b(n) is comprised of two factors and ~ appears

in both. The dcIay discount faclor wil~ inerease with ~ for each n, which means less

discollllting hecausc the highcr servicc rale will cause less dclay in lhe qucue for givcll

arrival rales. However, the olher faclor will decrease wilh ~ because there will be more

creative clcqruction which shortens the expected lifetime of each monopoly and hence its value.

The final result of these two opposing effects is still under investigation.

3.0thcr issues not yet studied and suggestiolls for new directions

There is a wide range of issues ,till to be invesligated 'in this extension of A&H. Instead of listing them in detail, wc shall raise here whal is perhaps lhe central problem in

403

I

bOlh models and lhal is lhe funclioning of lhe sequence of 1Il0nopoltes In lhe inlermediate good seclor.

A&H took great care lo show lhe condilions under which each new monopolist will: (a) be able to wipe out the previous incumbent from lhe market for the intermediate-lhe discussion of draslic or non-drastic innovations; (b) nol have an incentive lo do research himse1f-lhe replacement versus the rent dissipation effecl; and (c) nol acl slralegically to delay the arrival of lhe nexl innovalion by increasing his demand for skilled labour and t'JUs inducing higher wage rales ih lhe research sector - the strategic monopsonic effecl.

The lag between innovations and adóptions will probably introduce modifications to ali of these conditions.

However, almost all the conditions for restricting and simplifying the behaviour of each monopolist used by A&H and hence here, had some arbitrary and/or objectionable feature. For example, the conditions (a) to justify the monopolist wiping out the previous incumbent is an imperfect equilibrium in the game theoretic sense, for the case of non-drastic innovations. As they point out at the end of Section 6, profits can

be higher for.the incoming monopolist if he were to offer to share these wilh lhe previous

incumbent who, in return, would agree not to compete, even though the higher price charged makes continued production viable for him.

The strategic monopsonic effect is ignored by A&H'because it derives from lhe othcrs - that there will survive only one inlermediate firm between each innovalion/adoption.Their suggesled remedy - many different intemlediate goods, each a local monopoly and cach needed as input to the consumer good, is virtually a new mode!. Introducing our queue there may be one (Jossible line of future research.

The real challenge though, would seem to be a direction in which one can get coexistence of firms producing different qualities (vintages) of the same intennediate, and where the demand-side resistance is more coherently integrated with thespecification of consumer preferences. Then we should be better equipped to tackle the international economy.

404

;

.0

References

Aghion, Philippe ahd Peter Howitt (1992), "A model of growth through creative

destruction", Ecol/ometrica 60, March, 323-351.

Aghion, Philippe and Peter Howitt (1992), "Endogenous technical change: The Schumpeterian perspective'\ paper presented at the Kiel Institute Conference on Economic Growth in the World Economy.

Bairoch, Paul (1982), "Intemational industrial leveis from 1750 to 1980", J. of Europ.

Econ. History 11,269-333

Grossman, Gene M. and E. Helpman (1991), Innovatiol/ and Growtlr in the Global

Economy, MIT Press.

Grossman, Gene M. and E. Helpman (199Ia), "Quality ladders in the thcory llf growth",

Revim' of Ecol/omic Stlldies 58, 43-61.

Lucas Jr, Robert (1988), "On the mechanics of economic development", 1. of Monet.

Econ. 22, 3-42.

Romer, Paul M. (1986),"lncreasing returns and long-run growth", J. of Pol. Ecoll. 94,

1002-37.

Romer, Paul M. ( 1990)," Endogenous technical change", 1. of Pol. EcO/I. 98,71- \02.

Scott, Maurice FitzGerald (1989), A New View of Economic GrolVtlr, Oxford U.P.

Tirole, Jean (1988), Tire 17leory of Industrial Organization, MIT Press.

Wagner, Harvey (1969), Principies ofOperations Research, Prentice-Hal!.

Figure 1 research firms monopolist

J.

OOm

t1i

innovations consumer good firms____________________________ v

Innovations-- 1- ---1- ---1- ---1- --

time 't Figure 2 t t+1 t+2 t+3 Adoptio n s--1---

---1---~1 t t+1 ____________________________ v Figure3

I"---

...\

....

c(nt).b(nt+ 1)"

~o

n3 ns nO n2 n1 n4Data for Figure 3 :

Discovered In UseJ:at Adoptions Lag

NO

NO

at 1O·

O

O·

2O

O

3

1 1 1 4 3 2O

S

3

O

t+ 1 t-i at• assumes no innovation in queue ai slart-up

406 nm nt~ time 't 1 ••

---~~~---

,-r

Jl:filD IlEN IOI.UIMONSEN