A REUMATOLOGIA NAS ARTES PLÁSTICAS

RHEUMATOLOGY IN ART

Telo de Morais

Hospitais da Universidade de Coimbra Hospitals of the University of Coimbra

A R E U M A T O L O G I A N A S A R T E S P L Á S T I C A S

R H E U M A T O L O G Y I N A R T

Telo de Morais

*Many thinkers, especially philosophers, have de-bated the idea of beautiful, as well as of what Art is, and what its traits, parameters and aims are. The vast majority considers that art is obtained when one is able to reach what is beautiful. But what is beautiful anyway? An object, a living being corre-sponding to an universally recognised ideal and lacking a concept? What causes liking, an aim wi-thout end, still in the line of Kant? Or, according to Hegel, beautiful is “the sensitive manifestation of what is true”? Let us add that it can be faced as fol-lowing: semantically, psychologically, metaphysi-cally, ethically and axiologically. The latter is more applicable to contemporary thought, since beauty is, in itself, a value, independent of what is real and metaphysical. For Scheler, the aesthetic values are spiritual and superior to the vital and useful ones. Bearing in mind the planned topic, we are in-terested in assembling some statements by Mar-tin Heidegger, contained in his book The Origin of the Work of Art. Here are some of them:

‘Where and how does art exist? Art is nothing but a word to which nothing real corresponds any-more. It can exist as a collective idea in which we gather all those things, which only in art are real: the works and the artists’.

‘The philosopher by faith can guarantee that God has created all things, all human and non human beings, but not the matter-form, nor even the equipment, and even less the works of art. These are men’s creations.’

‘The truth means today, and since long ago, a harmony between knowledge and its objective (...) But this essence of the truth, to us current, the right-ness of representation (Vorstellen) depends abso-lutely on the truth as non concealment.’

‘The putting-to-work-of-truth makes the dis-quieted abyss arise, and subverts the familiar and that which is considered so. (...) art is, in its essen-Muitos pensadores, em especial filósofos,

discuti-ram a noção do belo, bem como o que é a Arte, seus atributos, parâmetros e finalidades. A grande maio-ria considera que a arte se cumpre quando atinge o belo. Mas, afinal o que é o belo? Um objecto, um ser vivo que corresponde a um ideal uni-versalmente aceite e sem necessidade de conceito? O que causa agrado, finalidade sem fim, ainda na linha de Kant? Ou, segundo Hegel, o belo é «a mani-festação sensível do verdadeiro»? Acrescente-se que ele pode ser encarado dos seguintes modos: semântico, psicológico, metafísico, ético e axio-lógico. Este último é o mais aplicável ao pensa-mento contemporâneo, pois que a beleza é, por si mesma, um valor, independente do real e do me-tafísico. Para Scheler os valores estéticos são es-pirituais e superiores aos vitais e aos de utilidade.

Tendo em mente o tema proposto, interessa--nos respigar algumas afirmações de Martin Hei-degger contidas no seu livro «A Origem da Obra de Arte». Eis uma pequena parte delas:

«Onde e como é que há arte? A Arte não é mais do que uma palavra à qual nada de real já corres-ponde. Pode valer como uma ideia colectiva na qual reunimos aquelas coisas que da arte somente são reais: as obras e os artistas.»

«O filósofo pela fé pode asseverar que Deus criou todas as coisas, todos os entes humanos e não hu-manos, mas não a matéria-forma e nem sequer apetrechos, muito menos obras de arte. Estas cria-ções cabem ao homem.»

Verdade quer dizer hoje, e desde há muito, a concordância do conhecimento com o seu objecto.» ... «Mas esta essência da verdade, para nós corrente, a justeza da representação (Vorstellen) depende em absoluto da verdade como desocultação.»

«O por-em-obra-da-verdade faz irromper o abismo intranquilizante, e subverte o familiar e o que se tem como tal.» «...a arte é, na sua essência,

*Chefe de Serviço jubilado de Imagiologia dos Hospitais da Universidade de Coimbra

*Jubilee Head of Service of Imageology, Hospitals of the University of Coimbra

uma origem: um modo eminente como a verdade se torna ente, isto é, história.»

Sobretudo os dois últimos parágrafos explicam a razão que tem levado tantos artistas a represen-tar seres humanos com doenças que, por serem deformantes, sobressaem em pinturas famosas e até em esculturas de insólito grotesco ocorrendo nas mais antigas. Executadas na época greco-ro-mana, encontram-se reproduzidas numa impor-tante publicação belga editada em Bruxelas e inti-tulada «Les affections rhumatismales dans l’art e dans l’histoire» com a colaboração de distintos autores, sob a direcção de Thierry Appelboom.

Na pintura, foi especialmente durante os perío-dos renascentista e barroco que enfermos reuma-tismais surgiram em quadros de mestres de reno-me mundial. Sublinhe-se, no entanto, que, muitas vezes, estabelecer um diagnóstico por intermédio de obras pictóricas não passa de mera presunção. Já o não menos documentado livro «La Reu-matologia en el Arte» do nosso bem conhecido e apreciado Professor António Castillo e da Dr.ª Sonsoles Castillo Aguilar, dado à estampa pela Editorial Médica Internacional S.A. no ano anteri-or ao do já citado, igualmente enriquecido com numerosas reproduções, se espraia por belas obras da mitologia e por doenças de diferentes etiopatogenias, desde afecções congénitas, in-cluindo o nanismo acondroplásico, a picnodisos-tose e a de Ehlers-Danlos, a poliomielite, tinhas, a enorme rinofima do magistral quadro de Ghirlan-daio «Retrato de um velho com um menino».

É, de facto, ponto assente que o belo (bom, em nosso entender) e o bonito nem sempre coinci-dem. A obra de arte, toda aquela que é digna de ser apelidada desta maneira, não depende do bonito, do que é lindo. É antes o resultado dos seus valores estéticos e de verdade autêntica, imanente.

Entrando no campo da patologia e com o pro-pósito de não repetir texto e iconografia das exce-lentes publicações já referidas, comecemos pela espondilite anquilosante ou ancilosante que, en-tre as várias designações, conta com as de es-pondilite reumatóide e de pelvieses-pondilite reu-matismal.

Como é sabido, anatomopatologicamente tra-ta-se de um processo inflamatório crónico que em mais de metade dos casos se inicia por uma sín-drome sacro-ilíaca (sacro-iliite) bilateral e dolorosa. Seguem-se fenómenos de entesopatia como consequência da calcificação ligamentar, con-drólise, necrose fibrinóide da cartilagem, a qual

ce, an origin: an eminent way of turning the truth into being, that is, history.’

The two last paragraphs, mainly, explain the reason which as led so many artists to represent diseased human beings that, for being deformed, stand out in famous paintings and even sculp-tures of unusual grotesque, which appear in the most ancient of them. Executed in the Greco-ro-man period, they are reproduced as part of an important Belgian publication edited in Brussels under the title Les affections rhumatismales dans l’art et dans l’histoire, counting on the co-opera-tion of several distinguished authors and the organisation of Thierry Appelboom.

In painting, it was especially between the re-naissance and the baroque that people with rheumatic infirmities appeared in paintings by worldly renowned masters. However, it should be highlighted that establishing a diagnosis through pictorial works is often but mere conjecture.

The also well documented book La Reumatolo-gia en el Arte by the well-known and appreciated Professor António Castillo and Dr. Sonsoles Castillo Aguilar, edited by Editorial Médica Inter-nacional S.A. in year before the already men-tioned one, and also enriched by plenty of repro-ductions, extends itself through beautiful works of mythology and through diseases of different etiopatogenies, going from congenital condi-tions, including acondroplasic dwarfism, picno-disostosis and Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, polio-myelitis, tinea, the enormous rinophima in the magisterial painting by Ghirlandaio, “Portrait of an old man with a boy”.

In effect, it is common knowledge that what is beautiful (good, in our point of view) and handso-me do not always coincide. The work of art wor-thy of so being called does not depend upon what is handsome, upon what is pretty. Then again, it results from its aesthetic values and of authentic, immanent truth.

Entering the field of pathology, and trying not to be repetitive in terms of text and iconography of the already mentioned excellent published works, we would like to start with ankylosing or anchylosing spondylitis, that, among other desi-gnations, is called rheumatoid spondylitis and rheumatic pelviespondylitis.

As it is known, in terms of anatomopatology it is a chronic inflammatory process initiated in over half of cases by a bi-lateral and painful sa-croiliac syndrome (sacroiliitis). Here follow en-A R E U M en-AT O L O G I en-A N en-A S en-A R T E S P L Á S T I C en-A S / R H E U M AT O L O G Y I N A R T

tesopathy phenomena as a con-sequence of tendon calcification, chondrolysis, and cartilage fi-brinoid necrosis, which usually evolves into sinostosis. Then co-mes the typical radiological look of a “bamboo spine”. From the outside, the kytosis with rigidi-ty in the cervical region itself (Fig. 1 and 2).

This medical condition, as well as chronic evolutive polyarthritis (CEP) in adolescents and adults, Reiter’s Syndrome and psoriasic arthritis, are the main inflamma-Figura 1. Grécia, 510-500 a.C. – «Relevo em mármore»

(pormenor) – Museu Nacional de Atenas. Cena em que dois jovens se divertem conduzindo uma luta entre um cão e um gato. Dos assistentes, um deles ampara-se no ombro do jovem que segura o gato e também numa ben-gala que usa na mão esquerda, sofre da coluna, com pro-nunciada cifose dorsal. É manifesta a grande dificuldade em se movimentar.

Greece, 510-500 a.C. – “Relievo in marble” (detail) – Na-tional Museum of Athens. Scene in which two young peo-ple entertain themselves with a fight between a dog and a cat. Two spectators, one of which is leaning onto the shoulder of the young man holding the cat and also on a cane in his left hand. He suffers from his back and has a distinct dorsal kiphosis. The great difficulty in moving is obvious.

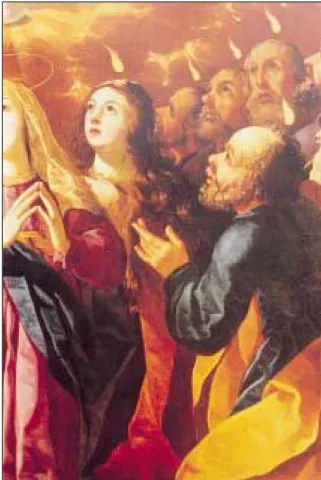

Figura 2. Josefa de Ayala (mais conhecida por Josefa de

Óbidos) – «Pentecostes» (pormenor), cerca de 1650--1660. O apóstolo S. Pedro revela gibosidade dorsal e mo-derada deformação das mãos.

Josefa de Ayala (better known as Josefa de Óbidos), “Pentecostes” (detail), approximately 1650-1660. The apostle Peter reveals dorsal gibbosity and moderate hand deformation.

geralmente evolui para a sinostose. Surge, então, o típico aspecto radiológico de coluna em «cana de bambu». Exteriormente a cifose com rigidez atin-ge a própria região cervical (Fig. 1 e 2).

Esta afecção, bem como a poliartrite crónica evolutiva (P.C.E.) do adolescente e do adulto, a síndrome de Reiter e a artrite psoriásica, cons-tituem as principais síndromes da poliartrite inflamatória (PAI, em língua inglesa API).

A artrite degenerativa ou artrose é, pelo me-nos em parte, consequência do envelhecimento da pessoa e, por isso, bastante frequente, com maior incidência na mulher após a menopausa. Ataca diversas articulações, sendo particular-mente detectável nas metacarpofalangicas e nas interfalangicas.

O aspecto é o de nódulos de predomínio dorsal sobre excrescências ósseas. Nas interfalangicas distais denominam-se nódulos de Heberden e nas proximais nódulos de Bouchard (Fig. 3, 4 e 5).

tory polyarthritis (IPA, in Portuguese PAI) conditions.

Degenerative arthritis or arthrosis is,

at least partially, a consequence of ageing and, thus, very frequently, affects espe-cially women after the menopause. It harms several joints, being especially identifiable in metacarpo-phalangeal and interphalangeal joints.

Its appearance is of a predominance of dorsal nodules over bone excrescence. In the distal interphalangeal joints they are called Heberden nodules, as in the proxi-mal interphalangeal joints they are na-med Bouchard nodules (Fig. 3, 4 and 5).

A systemic rheumatic disease,

rheu-matoid arthritis occurs preferably in the

small joints. In the hands as in the feet, proximal interphalangeal, metacarpo-phalangeal and metatarsometacarpo-phalangeal, carpo and tarso joints are mainly affec-ted. Restricting ourselves solely to what matters, changes in the adjacent periar-ticular soft tissues, dislocations, luxations and consequent deformities are to be referred. Concerning the hands, we can then detect fingers in ‘boutonniere’, resulting from the flexure posi-tion of the proximal interphalangeal joints and hyperextension of the distal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 6).

A R E U M AT O L O G I A N A S A R T E S P L Á S T I C A S / R H E U M AT O L O G Y I N A R T

Figura 5. Mestre do Sardoal ou monogramista MN (antiga

atribui-ção) - «S. Pedro», 1º quartel do séc. XVI, Sardoal, Igreja Matriz. Sinais de artrose, embora o 2º, 3º e 4º dedos esbocem encurvamento em «botoeira».

Master of Sardoal or MN monogrammer (ancient attribution) – “Saint Peter”, 1st quarter of the sixteenth century, Sardoal, Igreja Matriz. Signs of arthrosis, although the 2nd, 3rd and 4th fingers show ‘boutonniere’ deformity.

Doença reumática sistémica, a artrite reuma-tóide mostra preferência pelas pequenas articu-lações. Quer nas mãos, quer nos pés, as interfa-langicas proximais, metacarpo e metatarsofalan-gicas, carpo e tarso são locais de eleição. Cingin-do-nos apenas ao que importa, refiram-se

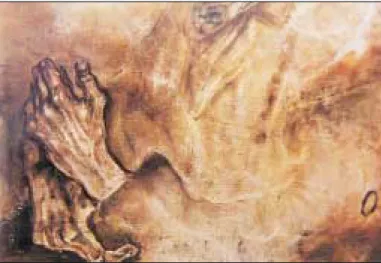

altera-Figuras 3 e 4: Oskar Kokoshka – «Retrato de A.Forel» e pormenor

das mãos com os típicos nódulos desta afecção – Museu estatal, Mannheim.

Oskar Kokoshka – Portrait of A. Forel” and detail of hands with the nodules typical to this condition – State Museum, Mannheim.

ções dos tecidos moles periarticulares adjacentes, desalinhamentos, luxações e consequentes deformidades. A nível das mãos vêem-se, então, dedos em «botoeira» que resultam da posição de flexão das interfalangicas proximais e hiperextensão das interfalangicas

dis-We believe that it is not possible to classify the cause of hand deformation, a specificity that can be identified in the figures of the mentioned Mas-ter of Sardoal, such as in the magnificent pain-tings (Fig. 7 and 8).

As to chronic gouty arthropathy, it is cha-racterised by the presence of topha, which com-monly appear at a later stage. They are detected in the soft tissues of the auricular pavilion, feet, hands, etc. The periarticular topha are set eccen-trically along the extensor surface (Fig. 9). In this condition, some topha reach the cortical of the tubular bones or subcondral bone, but in the lat-ter mentioned areas, as well, besides, in other tis-sue or topographic locations, are not important to the discussed topic.

It is called psoriasic arthropathy, because in approximately 15% of the cases it is not distin-guished from rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and also because it causes spindle-shaped tumefaction of the soft tissues, with ‘sausage’ fingers. As to the rest, in terms of criteria for diagnosis, the absence of the rheumatoid factor is relevant.

Focusing on deformation in the hands was a notorious circumstance, since they are as evident in the works of many famous artists, expressing the visible reality, Hegel’s “thruth”. Nevertheless, we do admit that in the case the Masters of Sardoal (Fig. 10) and of the retable of Abrantes (Fig. 11) it is nothing more than a mere question of style.

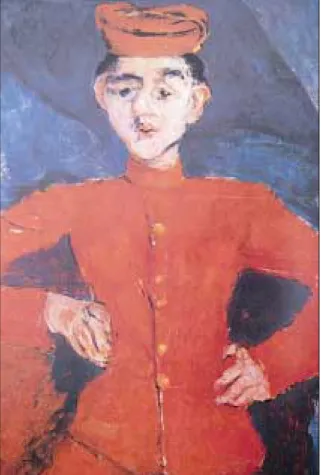

In Fig. 12, the hallux-valgus of the baby Jesus Figura 6. Chaim Soutine – «Le chasseur de chez

Maxim’s». Este jovem adulto, corretor de profissão, possui mãos de inequívoca artrite reumatóide. Também os dedos podem apresentar-se em «pescoço de cisne» por flexão metacarpofalangica e interfalangica distal, com hiperexten-são interfalangica proximal. Em alguns casos o polegar as-sume morfologia em Z ou em «baioneta».

Chaim Soutine , “Le chasseur de chez Maxim’s”. This young man, a broker, has un-doubtedly signs of rheumatoid arthritis in his hands. The fingers can also be in ‘swan-neck’, through flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joint and distal interphalangeal joint, with hy-perextension of the proximal interphalangeal joint. In some cases, the thumb shows mor-phology in Z-shape or ‘hitchhikers’ thumb’.

Figura 7. «Assunção da Virgem» (pormenor) – Museu Nacional de

Machado de Castro.

tais (Fig. 6).

Cremos não poder classificar a causa da defor-mação das mãos, particularidade identificável nas nas figuras do mencionado Mestre do Sardoal como, por exemplo, nos magníficos quadros ex-postos nas Figuras 7e 8.

Quanto à artropatia gotosa crónica, ca-racteriza-se pela presença de tofos que em regra aparecem numa fase tardia. Detectam-se nos teci-dos moles do pavilhão auricular, pé, mão, etc... Os periarticulares dispõem-se excentricamente ao longo da superfície extensora (Fig. 9). Nesta afec-ção alguns tofos atingem a cortical dos ossos tubu-lares ou osso subcondral, mas estas últimas zonas, como, aliás outras localizações teciduais ou to-pográficas, não importam ao tema proposto.

Nomeia-se a artropatia psoriásica porque em cerca de 15% dos casos ela é indistinguível da artrite reumatóide (AR) e ainda por causar tume-facção fusiforme dos tecidos moles, com dedos em «salsicha». De resto, nos critérios de diagnós-tico, é relevante a ausência de factor reumatóide. Foi notória a ênfase dada à deformação das mãos, visto que elas são tão evidentes nas obras de muitos artistas célebres, traduzindo a

reali-A R E U M reali-AT O L O G I reali-A N reali-A S reali-A R T E S P L Á S T I C reali-A S / R H E U M AT O L O G Y I N A R T

Figura 10. «Calvário» (pormenor), cerca de 1500 –

Igre-ja da Misericórdia.

“Calvário” (detail),approximately 1500 – Misericórdia Church.

Figura 8. «S. Vicente» (pormenor) – Museu

de Beja.

“Saint Vincent” (detail) – in the Museum of Beja

Figura 9. Jack Levine – «Benvinda a casa». Lauto repasto sugestivo de

pacientes gotosos. Deformação das mãos dos quatro homens idosos, em dois dos quais se distingue ingurgitamento vascular nas têmporas. Jack Levine – “Welcome Home”. Lavish meal suggesting patients with gout. Deformations in the hands of four elderly men, being that in two of them we can observe vascular swelling in the temples.

dade visível, o «verdadeiro» de Hegel. Admitimos, porém, que nos casos do mestre do Sardoal (Fig. 10) e do mestre do retábulo de Abrantes de Frei Carlos (Fig. 11), se trate antes de simples questões de estilo.

Já na Figura 12, o inquestionável hallux-valgus do Menino Deus deverá ser atribuído ao modelo escolhido pela nossa afamada pintora.

Demonstrada a tese que o feio, aquilo a que alguém chama o «belo horrível», incluindo a doença, os aleijões, podem integrar a obra de arte e até valer como tema central, recorde-se, entre outras, a «fase negra» de Goya, a trágica «Parábo-la dos cegos», 1568, de Pieter Brueghel – Galeria Nacional de Capodimonte, Nápoles.

Mais recentemente, a deformação física do ho-mem artisticamente provocada, propositada, verificou-se na Escultura com: Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, Kenneth Armitage, Eduardo

is already unquestionable, which should be ascribed to the model chosen by our famous painter.

Being thus the thesis demonstrated, that what is ugly (what someone called the “horrible beau-ty”, including diseases, deformities, can be a part of the work of art and even be given the place of main theme. We should remember, among oth-ers, Goya’s “dark phase”, the tragic “Parable of the Blind”, 1568, by Pieter Brueghel, National Gallery of Capodimonte, Naples.

More recently, men’s artistically provoked physical deformation, intended, is presented in sculpting in the works of Henry Moore, Alberto Giacometti, Kenneth Arrnitage, Eduardo PaoIoz-zi, etc., and in painting in the works of James Ensor, PabIo Picasso, Asger Jom, André Masson, Jean Dubuffet, Francis Bacon, as well as in many others. How many wonderful works of art! Figura 11. De Frei Carlos, «Aparição de Cristo à Virgem»

(pormenor), 1529 – Lisboa, Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga. “Aparição de Cristo à Virgem” (detail), by Friar Carlos, 1529 – Lisbon, National Museum of Ancient Art

Figura 12. Josefa de Ayala - «O Menino Jesus Salvador do

Mundo» – cerca de 1660-1670,

by Josefa de Ayala,“O Menino Jesus Salvador do Mundo”, approximately 1660-1670,

A R E U M AT O L O G I A N A S A R T E S P L Á S T I C A S / R H E U M AT O L O G Y I N A R T

To conclude, we choose a painting (fragment) by the young painter Sara Maia (Fig. 13), already represented in the Berardo and Culturgest Collections, which speaks for itself. None the less, about these unusual characters, Susana Neves concludes her lucid criticism the following way:

“...They derive from an authentic impulse and readdress the notion of Beau-tiful. Shaking the usual identification between beauty and being agreeable, they broaden the concept to introduce into it the value of the strength which agitates the image, making it unforgettable and polemic.

The antithesis of boredom.”

As a conclusion, this extract corrobo-rates our perspective.

Figura 13. Quadro de Sara Maia.

Sara Maya’s picture.

Paolozzi, etc., e, na Pintura: James Ensor, Pablo Picasso, Asger Jorn, André Masson, Jean Dubuf-fet, Francis Bacon e bastantes mais. Quantas ma-ravilhosas obras de arte!

A finalizar, escolhemos um quadro (fragmen-to) Fig. 13, da jovem pintora Sara Maia, represen-tada já nas Colecções Berardo e Culturgest, que fala por si. Não obstante, Susana Neves àcerca destas invulgares personagens, conclui assim sua lúcida crítica:

«... Derivam de um impulso autêntico e reequa-cionam a noção do Belo. Sacudindo a habitual identificação de beleza com o ser agradável alargam o conceito para inserir nele o valor da força que agita a imagem, tornando-a inesquecí-vel e polémica.

A antítese do tédio.»

Este excerto vem corroborar, como remate, o nosso parecer.