The printing of this book was sponsoted by: der Uni/'mitdt Graz and vr:.,,_,.,L,::; urld Forschung dee Steiermdrkischen Landesregierung

Das Land

ermarkl

. -.... --. .-.~ -+ '1.fissenschaft und Forschung1)1bHograpluc Infotmadon publisbed by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek. 1he Deutsche Nationalbibliotbek lists tbis Dublicatioll in Ibe Deutsche NO!Jnn:llh, detailed data are available

ISBN 9783·593·59612,5

All rightl reserved. No paft of this book may be reproduced

means. electronic or mechanical, including or by "flY information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing ftom rbe publishers.

Copyright 2012 Campus Vedag GmbH, Frankfu1t-oll,Main Cover Campus Frankfllrt-on-Main

Cover illustration: www.fotolia.com/adamgolabek

Priming office and bookbinder: Beltz Druckpartner, Hemsbach Prill ted on acid Cree paper.

Printed in Germany

This book is also available an E·Book. For further information:

www.campus.de

Content

Introduction

1 Determinants

Effects of

Identity

Postmodern Ethnicity: Diversity and Difference

Albert 1;: Reiterer... 21

National Pride, Patriotism and Natiomlisrn: Methodolocical Ref1ections and Empirical

and Helmut lGt=vtlics... 45

National Identity and Attitudes towards Imrrup,-;rar in a Comparative

t·'ala and Rtli COJta-LojJe.l' 71

AIirosltn' 101

A Success

The Vision Kambarage Nyerere

Bell1adette lvIi/ller ...125

'Cntations of Atrocities and TIle Case of Darfur

l1le printing of ,his book was sponsored by: Forscimn'Esservice der Universitat Graz and

IPa~Land

?!~~!maYkl

~ llj'IJ'i3senschaft und F orschung

I:>lDllograpmc Information by the Demsche Nationalbibliothek.

The Deutsche Nationalbibliolhek lists rhis publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; derailed data are available in the Internet http://dnb.d-nb.de.

ISBl' 978-'3-593-3%12-5

rcproaucea or transmitted in any form Of by any means, electronic or mechanical, recording, or by any information storage and rccri",-"l system, without permission

© 2012 Campus Verlag GmbH, Frankfurr-on-Maln Cover design: Frankfurt-on-Main

CAYver illustration: w,vw'.loto.lia.coml'adanlgc)iaiJek

Printing office and bookbinder: Beltz Druckpanner, Hemsbach Printed on acid iree paper.

Printed in Germany

'[his book is a.Iso available as an E-Book. For Furrher information:

6 CONTENT

Prom

dllUllt11to Transnational Identity

The Boundaries

179 lVIF'rnnnT Trace

in the Central Countries

\ITalldalena hrcovd and lvHIIJ.riav Bahna ...201 Political Unification and the

On the Social Basis of Euro\Jca,n

ImtJJerf;ill ... 22·1 All or

lVlarkus

National and Transnational Identities of

l\ii(/J(.Jei BraNn and Walter Muller'

"Interethnic Alliances" and National An Analysis of Internet Fora Related to

Dieter Reicher

Institutional Tbeories of Education Supra-National

W

List of Scientific Publications of Max Hallcr.. ... 331

National Identity and Attitudes to\vards

Immigrants in a Comparative Perspective

1Jorge

Rui

i

I

National identity is one of the processes through which people huild a collecdve identity, by with others beliefs and memories about the nation. The Internadonal Social Survey Program of 2003/2004 on National IdeIltity asked respondents the importance attributed to a nation, family, and social

ethnic, religious and political group, in terms of its impact on their per sonal self-definition. 12 percent of the cidzeIls of a number of Euro pean Union countries2 considered nationality as a factor with

partance to their ranking below family and

sional group in the set of EU countries considered. In the same vein, 48

percent of EU citizens feel identified with the countries.

In this chapter we will the association herv;een the salience of a national identification and the contents comprised in that national

"iJ'_Lll.ll-'tily

and the attitudes towards those who do not share the same nation-towards l.UIHllF;"Ul

This question builds on an in.itial premise that emerges from Social Theory (SIT, Tajfel/Turner 1 This theory considers that the

of social has an impact on the we

think and act. Specifically, the of belonging to social or

group is an important dimension of personal identity. Moreover, the inte gration of this membership in the individual's self-definition often carries effects on the way we react to members of the group we belong to

and the members of the groups we do not belong (outgroups).

1 A version of this paper was included in the book Inc/usioll

Social Exclusion by Jose Sabra! and Vah and etUted by Imprensa de

Ciencias Sociais using part of the damselS considered here.

2 Countries from the EU (at the time of data collection) present in ISSP: Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and UK

72 JORGE \'.\LA !\I\D RCI COSTA-LoPES 73

However, not all groups have the same importance in our self-defini tion and, consequently, not all groups will have the same impact on the organization of our behaviour and attitudes. One of the factors determin ing the weight that a certain group has on the individual's behaviour, per ceptions and attitudes is not only the group membership in itself but also the strength of the feeling associated to that membership, i.e. the degree of identification (Ellemers et al. 1999). On our part, we propose that the meanings associated with these identities determine the orientation and intensity of intergroup attitudes.

Given the importance that national identity assumes, as shown by the data referred above, one should expect it to have a significant impact on the way we construe our relationship between those who share and those who do not share our national membership. In fact, this issue, and specifi cally the relationship between national identity and attitudes towards

immi

gration, is a topic of recurrent debate in the political arena in general (O'Rourke/Sinnott 2006). Thus, we approach an open issue and one which reaches today a particular acuteness'.

In the first part of this chapter we draw a brief overview of the studies on national identity and its impact on attitudes towards relevant OlltgroUpS and we present the hypotheses underlying the two studies that were carried out. The second part presents the first study: using ISSP and ESS (Euro pean Social Survey) data, we analyze the importance of a comparative ap proach to national identification (identification with the nation vs. identifi cation with Europe) in order to better understand its relationship with attitudes towards immigration. The third part presents tl1e second study that analyzes the impact of the meanings of identification (nationalism vs. patriotism) on the opposition to immigration and on the perception of immigrants as a threat. This second study was based on ISSP data. This chapter is thus framed by three important perspectives on the approach to national identity that are exceptionally personified in the oeuvre of Max Haller (e.g. Haller 1999; Haller/Rosegger 2003; Haller et al. 2009): the comparative perspective, the relationship between national identity and European identity and the impact of the meanings of national identity. We

3 For example, the debate on national identity promoted in France by President Sarkozy and his government elicited, by December the 30,h, 2009, 23,000 reactions registered in the official site of the debate. 40 percent of those reactions evoke topics related with immigration (see Le i>1onde 2010, January 7).

NATIO"AL IDENTITY AND ATTITCDES TOWARDS I;'OnGR.\NTS

combine these three aspects for providing a contribution to ilie under standing of attitudes towards immigrants and immigration.

National identity and intergroup attitudes:

a puzzling relationship

Social psychology literature hesitates to associate ingroup identification and negative attitudes towards other groups (e.g. McGarty 2001). In fact, the main theory about the topic in this disciplinary domain, Social Identity Theory (Tajfel/Turner 1979), has elicited approaches and empirical studies with ambiguous or even contradicting results on this matter. This theory defines social identity as a part of the individual's identity that derives from belonging to groups and the value associated '.\7ith that group membership. One of the fundamental tenets of the theory is that individuals like to think positively about the groups to which they belong because their self-esteem derives, at least in part, from a positive social identity. On the other hand, a positive social identity depends on a positive evaluation of the ingroup compared with relevant outgroups. Thus, we can explain both the emer gence of ingroup favouritism but also the derogation of other groups (out groups) (Tajfel/Turner 1979). That is, building on this theory, we should assume that the higher the identification with a group, the higher the fa vouritism towards that group and its members and, most likely, the stronger the negative attitudes towards other groups and the people within them.

For example, in the specific case of the relationship between national identification and attitudes towards immigrants, in a study conducted '.vith representative samples of four European countries (France, Germany,

Great Britain and the Netherlands), Pettigrew and Meertens (1995) showed

that the higher the identification with a nation, the higher the orientation for prejudice and discrimination of immigrants. Also Blank and Schmidt (1997, cited in Blank/Schmidt 2003) found empirical support for the exist ence of such a relationship using correlational data from national repre sentative samples (ISSP 1995: Austria, Italy, Germany, Russia, UK and USA). More recently, Wagner and colleagues (\\!agner et al. 2007) analysed the correlation between the level of national identification and the deroga tion of immigrants using longitudinal data from 600 German citizens.

74

JORGE V,UA ~~'-i[) RCI COSL\two measure points, separated by four years, the authors showed that association to be indeed positive.

The question, however, may be more complex a systematic

a correlation between national

between national identity and ethnocentrism. In the same of the Eurobarometer 47.1 (1997), conducted in 15

did not reveal a significant correlation between national L

towards oeople of a "different race, or culture"

these results are consistent with the of the moderators of the relationship between identifica

tion and the derogation of significant In Hinkle and

Brown (1990) reviewed 14 studies that tested the relationship between identification and

since this did not state a direct relationship between ingroup identHication and outgroup derogation

(11cCarty 2OCJl; Mummendey 1995). This what the initial ex~

periment by Tajfel and coUeagues showed matri

ces that served to attribute points to an and an ingroup. The study demonstrated that people favour members of their groups in detri

ment of members of other groups when positive resources.

when participants were asked to attribute to their

and the outgroup inste,ld of this of

favouritism ceased to manifest itself This

showed that this bias of favouring the is of what we

feel about the outgroup. \Ve can thus think of a dissociation between a towards the corre be conditions that facilitate an associa tion between group identification and outgroup discrimination and that may help to explain results such as those from and Meertens (1995) in the context of migration. For Hinkle and Brown hn)othesized that the relationship between identification and a negative

bias towards other groups depends on factors. These authors

proposed that ingroup identification may have different meanings and developed a taxonomy of groups that includes two orthogonal dimensions: imlividuaJism vs. coUectivism (see Triandis and the relational vs.

autonomous orientation (orientation for or not). Considering

NAT10",AL AND ATTITCDES TOWARDS r~LMrCdA"TS

this taxonomy, Hinkle and Brown argue that the relationship between ingroup identification and attitudes towards other groups will emerge only for individuals or groups with a collectivist and relational

orientation of comparisons). Brown and

(1992) this hypothesis: the association benveen

ingroup identification and intergroup bias was higher in the collectivist-relational than in any other quadrant. Also ~'1ummendey, Klink and Brown showed that national identification and the derogation of other groups may be independent, but when the comparison between the and the outgroup is highly salient in a given context, then these circumstances do facilitate the emergence of a

between national identification and the derogation of other groups. In our view, it important to focus on studies that have shown the

about the nation on the

between national outgroup attitudes. For example,

some studies indicate that when a represented as a set of entities (Billiet et ai. and not as a the odds of a positive rela tionship between identification and outgroup derogation are smaller. One could in fact invoke this hypothesis to explain the absence of a

between national and negative attitudes towards Switzerland and the UK (ISSP2003/2004), the same happening In

(see Billiet et al.2003), cOtll1tries often construed as a set of entities. More over, it is to consider the representation of the history of the nation as an factor in the relationship between national identifi cation and towards other groups (Citrin et al. 2001;

Within that vein of emnhasizing: the role or the nrevalem represen

lation of the examined the

between national identification and tw~chpr of peace or outgroup in the case of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

It is also within this context of the nation's rq::,res:enl:atl,::ms that we nroposed an exolanation for

in

attitudes. In a

well as in a data from ISSP

or even the study using data from ESS-2/2004 Vala et aL 2(08) we obtain, contrarily to what happens in the set of the

other countries, a dissociation between the of identifica

--- --- ---

---76 JORGE '.1,1 :IND ReI COSTA-LOPES

acti,'adon of national identity in makes the

of colonization salient the idea that Portuguese have a natural that are seen as different a trait that would explain t.he unique character of Portuguese colonial relationships) and inhibits the expression of explicit attitudes towards those '_~HllU'"

from the colo_nies (even though t11e same doesn't happen with less ex-see Val a et a1. \X'ithin the several trans-national da tasets and the studies we have conducted so only one exception was found: a study on the memory about the of Brazil in ,vbicb it is

shown that those who identify more with Portugal have a more of the slaves and the Indians than those who idendfv less In the present study, we examine two sets of hypotheses not yet tested in the literature on this domain_ The tust set of hypotheses huilds on pre

vious studies on comparative its impact on atdtudes to

wards immigration and studies its role within the relationship between values and attitudes towards immigration (Ramos/Vala The second

set of points to the

on attitudes towards immigration_ in this second case, we

sUldy the effect of national identity construed as patriotism vs. nationalism on attitudes towards immigration. \'Ve argue that the consequences of national identity on inter(!roup attitudes are better lmderstood when na·

tional context; moreover, we argue that

than the degree of national identification are the contents included in this national

Comparative identity, values and opposition to immigration

Ros, Huici and Gomez noticed how most of the work

social identitv and intergroup comparisons and differentiations point built on binary comparisons between an ingroup and an outgroup. Ros and colleagues introduced, then, the concept of

;,-lp"t'''' that when one studies the consequences of group iden

one should take into account the relations hetween social self identifications at different levels of abstraction. It should be clear that the

comparative component of social does not here to the ex.ist

..

NAT]Ol\c,\L IDENTITY ACiD ATTlTCDES TO\'fARDS I~IM!GRA,\TS 77

ence or inexistence of a comparison with outgroups but instead to the that identification with ingroups at different levels of abstrac

tion may mean. 1hus, identity may be defined as the

son between degrees of identification with two groups in different levels of inclusion (e.g. identification with a specific nation and with Europe). Ros and sustain that simultaneously considering identifications with more than a ca tegory / grou p allows to hetter unders tand

tudes. Similarlv. Haller (1999) had already pointed at the importance of and European idemitv to better

under-identification with the country than with

lion to immigration, a hypothesis not yet tested within the

between nadonal identification and attitudes towards immi On the other hand, and follov;ring previous studies that have shown that ellalitarian values facilitate the ~(T('nl-"nrf' nf; mm;GrMlnn while

conservation values facilitate its

ine the ~""h~'h ~O; represents the lllt:Ulam

between social values and opposition to immigration. the effects of national identity and comparative national on the

To

identity to immi!!ration. we used data from the

ISSP-derived from a collaboration between the Institute of Social Sciences of the of Lisbon (ICS-liL) and tl1e team of social psychologists of the of Lausanne. This collaboration and the comparison we are

L:XaUllnmg here emerged from the interest of contrasting two countries that :tinguished in terms of the relation each countJ:y has towards the an institution that represents the values considered in the Thus, we contrast a country that has a st'lble and consolidated membership in the European Union for more than twenty years

with a country that is not formally part of it and limits its bilateral treaties and limited economic

To analyse the relations between comparative national

and opposition to immigration we used data from the ESS-2!2004 ob tained in PortlU'al. Switzerland and Poland. In this case, we used questions

79

78 VAL\ ANLJ RCI COSTA-LoPES

induded in the basic questionnaire about social values and OppOSlt10n to and two complementary questions, included in the Portu

guese, Swiss and PoUsh version of the from a collaboration

of Lausanne) and the Institute of Philoso

;)01c10102:1' of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

interest of including Poland in the comparison

COllUllUlllg this interest of 'whether these

relation-on the relatirelation-on each country has towards the European Un

ion, we added to the two previous a country that had onlv

re-the EU bv the time of data collection ~, h 4

Comparative and attitudes towards

The was

regression as independent

variables the measme of identification but also two indices on beliefs about

immigrants. One of these indices different variables that seek to

with immig-ration at the level of instrumemal economic relative Gepd at the economic: level);' the other index aspects related to

4 \X'e the scientific collaboration of Domhique Joye from FORS, l:niversity of Lausanne and Franciszek Sztabinski and Pavel Sztobinski from the Polish Academl' of

Scie-nces.

'S"fit',~d"nd

assessed with the indicator "How dose do you fed Answers were coded to vary between 1 (NOt at all) to 4

"Do you think the number nowadays should be [ ...]" 1 (Increased a lot)

to 5 (Decreased a lot).

Economic threat perception "Immigrants are for the l'ortuguesci

economy", with answers coded from 1 (tOtally 2!:,cree) to 5 (totally disagree); Economic relative deprivatjon "Comparing with the immigrants economic situarjon, how do YOll evaluate yOllr economic situation? Your sil""tioo is [.. .]", J (l\luch better tban the immigrants,) to 5 (Much worse); Negative interdependence "Which of the

foliowing starcments better to yom , where answers

were: "Portu[!uese/Swiss workers have interests incompatible with immilo'fants' workers and immigrants should defend their interests

NATIONAL IDENTITY AND i\TTlTCDES TO\;;',\RDS HIMIGRANTS

are a threat at the cultural procedural relative

neasuring symboUc: and instrumental aspects related to op to Immigration were introduced in the regression analysis as con trol variables of the effect of national

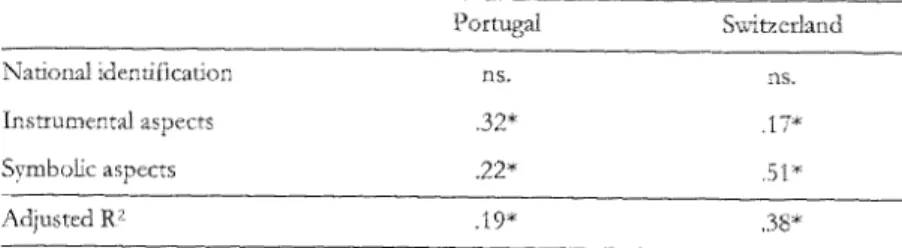

Table 1: on Switzerland National identification ns. ns. Instrumental aspects .32* .17* aspects .22* 51" .19* ,38* i\<1lUsted R"

Nofl:s: tI.f. nOt! StfPijlmnt .001

As described in Table 1, national identification in

is not a predictor of opposition to

tioned above_ this result

and with a representation of the country as a set of entities as opposed to one entity in t.he case of Switzerland. However, this result may simply indicate a dissociation between national identification and the derogation of other groups, as discussed and shown in

studi.es (sec Mummendey 1995; Brewer 1999), which would indicate that

national identification does not attj tudes (0

wards other groups or countries. this result indicate that

national identification, as other identifications, should be measured in a way when the is to assess the consequences of the sali

ence and of a given identifica60n on intergroup relations.

it be that when identification with the nation is hig-her than identification

with a superordinate category of the same attitudes

become ne!!ative? That is the question we now address.

8 Symbolic threat perception: "The culture aod values left by our ancestors will disappear in our country is not strongly controlled." Procedural relative deprivation: "In general, authorities are more sensitive to immigrants' than to the problems

people like you". In both cases, answers coded to vary between 1 (totally and 5 (totally agree).

-80 JOR(;E VAL~ ,~ND ReI COSTA-LoPES 81

et al. 1 Huict et al.

about the context of atti

tudes towards we propose that the

in identity terms, between the nation and a category such as

the hii2:her the a relevant outgroup,

such as the if we measure national it

we shaH obtain a measure of better reflects the salience and the of this dimension of social

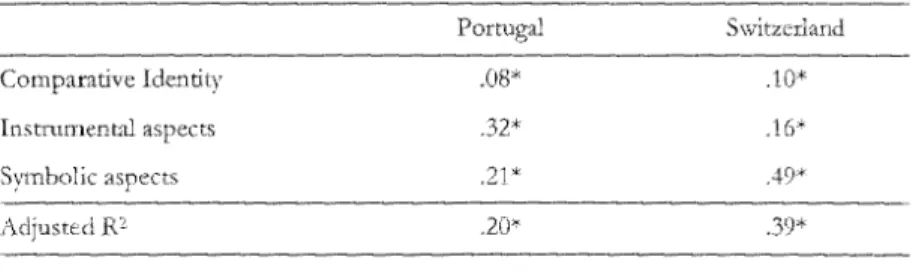

Table 2: lin Portugal Switzerland .08* .10* Instmrnental aspects .32* .16' aspects .4°*/ R2 .20'" .39* Notes:

*

p < .001To the effect of comparative Idenuty on OpposltJon to

we usc the same statistical procedures and ilie same control variables In this case, we observe (fable 2) that the higher the

identity, the higher the opposition to even when

,ve include in the same model. variables measuring- symbolic and instru mental aspects known to be potent in the explanation of attitudes towards

that the impact of

lower t11an the of threat

bolic and instmmental levels. Despite the bjstoric and current structural

the same pattern of response is obtained in and Swit

zerland.

9 identification was in an item that resulted from the

subtraction of the item of Identification with Europe ("How close do you fed to

Europe?)" from the item Identification with

NATlONi\L IDENTITY AND ,ATTITUDES TOWARDS IM)llGR.\NTS

national identity and attitudes towards HUHU,WlUUIl \X'e can now move further in the understanding of the role of

in determining attitudes towards In this new

we propose that the salience of comparative national

derives from values, i.e. is sustained constellation of

values and is inhibited we also propose

tl1at ulls comparative functions as a medi.ator of the effects of

social values on the evaluation

In

a study about the relationship between values and attitudes towards nigration in five countries (prance, Germany, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK), it has been shown that in aU analyzed countries with the exception of Portugal, the values defined by Schwartz (1 as self-trantolerance, concern for others and con

cern for nature) predict opposition to immigration. It was also

shown that the values of conservation of social order and social

countries

above, In the model we tested, the vallles of subset of

self-transcendence values related to the concern of

well-and conservation are considered Dredictors of oDDosition to immi

10 indicated how similar they thought the person described to be to

thcmsdves: "A man/woman that consi.ders importam that aU people in the world be

treated equally"; "A person who believes that everyone should have the same oppor tunities in !lEe'·; "A man/woman that considers important to listen to people who are different from hirnself/heJ:sel£"; person that even when with someone, still

wants to understand that person:' Answers were coded to vary between 1 ("Not at aU like me") to 6 ("Exactly like

82

JORGE VALA AND RU COSTA-LoPES83

The model predicts that the higher the COl'lservation, the the comparative identity; and the higher the comparative identity, the

the opposition to immigration. It also predicts that the the

universalisl'n, the hwer the comparative and the lower the opposi

tion to immigration.

These hypotheses were tested

Baron and Kenny

(1

ses arc dearly verified for all countries the values of conserva

tion. Concerning universalistic values, the was only verified for

Switzerland.

Results show, in all

opposition to the European identity national

from values of conservation and also that comparative is one of

the processes sustaining the relationship between conservation and oppo sition to immig:ration. The hypothesis that this same comparative identity is

related to universalistic values and mediates its to

for Switzerland.12

nationalism and are inde

pendent from universalistic but are Dositivelv associated in the

case of nationalism - or associated - in the case of europeism

to the values of conservation of social order. Probably in both countries,

and desDite their different historical paths and of

the of 1S

more 11eavlly Shaped by "instrumental" than universalistic values.

As a whole, these results indicate that to understand the of na

tional identity on the relation with other groups it is insufficient to

salience of identificadon, even comparative identification repre

sents an advancement on this domain. It is within this context

that we propose that to understand attitudes derived from na

tional identification. one should know the meanings associated to national

11 Respondents indicated "to what extent do you think [country] should :wow of a different race or ethnic gmup from most [country] to come and live here," Answers varied between 1 (Allow to 4 (Allow none).

121n and Poland, the effect of conservation is mediated

compararive identity: (Sobel test = p < .(J01); Poland (Sobel test 5.24. p <

NATIONAL IDENTITY AND ATTlTCDES TOWARDS I;VI:l!lGRANTS

1: between l!a/ueJ and to itt

mediateel !!Y (ESS-2/ 2004)

... ·!·~3h!) ..I9H ' -.14'"

...

".tI'''''''' ~ .19'** R'" [Q ~~ ... .16m .,!"'ft" to 112 Portf~gaj 2: ~ w(. .00 -.10"" ,06"~

Rl= .O~ ... ~ ... ll*H/f

.28"¥ ."",..",~"#!'" l~H' .,tJ!," Jlt!llfiIIIIf¥'~

84

J

O-RGE V ALA ."N D RCJ COST ,,-LOPES ]'.;ATIONAL IDENTITY AND ATTITeD TO\\-j\RDS IMMIGRA:-.iTS85

3: betlPerm value.> and oppoSItIOn to ZIT superiority and orientation towards and domination (Sidanius

mediated ~y identification (ES.\' 2/20(4) et a1. 1997; Bar-Tal 1993; Karazava is in this vein that Staub

(1997) distinguishes between blind (or nationalism) and

con-N everthcless what is really im

..

1!1 our analytlc is to know if this chstinction is present... ~

_.li9 h Y

_06 in common sense, even in an way, and also to know ,-vhether these

two dimensions of the content of national have different conse the relations between na

of contents national has been

Fcshbach and Sakano study which was

I

developed 1!1 the USA and in and that obtained similar factorialII

t ~'" structures for both countries in terms of four factors ''I'm

\:1"') IS'*'

,

~of being [ ...]"; "Being [ ...] is of my ,nationalism: "Conside

lj~ ring the moral and material of [...

J,

other countries should have~

2

forms of government similar to ours"; "The greater the influence of [ .. _] in

i

other countries, the better are"; internationalism: orientation towards

~

international cooperation; and civic libe/tie.>: orientation towards civic rights defense as the freedom to express points of view about the

country). These results were globally in Japan by Karazawa

National

patriotism, nationalism and attitudes

(2002). In turn, Huddy and I<hatib (2007) in a using data from theNational Social Survey (USA 1996), found three orthogonal factors:

immigration

national identity (deb'lee of and nationalism.

The that we now focus is to know whether national is There are a few studies that not onlv analyzed national idcntitv

con-or is not invested with different meanings in social thought and if those tents' but also

to different inter!!touo attitudes. and ethnocentrism. For results of a

on South Africa lared with ethnocentrism. In turn, Dowds and

data from ISSP, showed that exclusive nationalism correlates with xenonhobia. Also. Blank and Schmidt (20031. in studv dcvelooed in

entation toward competl is associated with tolerance and nationalism is associated

is consensual that these are distinct dimensions. with lower tolerance towards different foreigners.

after the work of [(osterman and Feshbach (1989; see also As a whole, results from these previous studies allow dIe formulation Feshbach 1987) and Staub (1997), patriotism has been associated with a of the hypothesis according to which common sense distinguishes between strong emotional connection to a country and its symbols and nationalism patriotism and nationalism, and that this first view of national identity is has been related to national identity contents like beliefs about the nation's dissociated from negative positions towards and perccption of

86 JORGE VM~A AND ReI COSTA-LoPES

and the second favors negative evaluations of immigration and the of immigrants as a threat both at the

level of resources.

To study these dimensions of national and their impact on atti

tudes toward we used data from collected in

and United Kingdom. These countries were chosen for three different approaches to state integration

et a1. J997). In fact, France represents a variation of an assimiiation ethnist ideoloQV and the UK

is

an of a civic111e indicators of nationalism and

most part hased on Kosterman and Feshbach (1989)'s scales.13 As depend

ent varialJles we measured both opposition to immigration and perception of symbolic threat (values and customs) and realistic threat (economic and

associated with immigrants (Stephan et al 2(05).

The first step of our study consistecl of a set of Confirmatory Factorial

of national . Following the literature

described above, we proposed the VDotheslS that these contents are orga' nized in tlvo correlated factors, Results shO\v indeed, in each and every country we obtained a solution with one factor of nationalism and one factor of patriotism15. We performed Confirmato

in each country and analyses of the indices showed a very

fit to the data in all 0 f them 16 4,5 and

13 Nationalism Indicators: "T having Portuguese ielentitv than the nationality of any other country in the world"; "11,c world would be a better place if people in other

were slrnilar to peoplel1

; "In generaL is a better cuuntry

than most other countries"; "People should support their country even when the country is wrong"; should defent! its interests even when that can lead to conflicts with other nations". Patriotism Indicators: "How proud are you of Portugal in each of lh" following: the way the democracy wotks; irs political influence .in the world; economic achievements; its social security system; its fair and equal treatment of all groups in the society; its hiswry,"

14 Since for this analytical step we were using items from the basic ql1estionnaire, common to all countries, we were able to include more countries in this analysis and it would not

infOlTI,aUVe or practical analyses in each country individually,

15 One item that would theoretically be includctl in the faclor of Patriortsm was excluded Wroutl of "Its history") as a preliminary analysis indicated that the model would better to the data if this item wasn't included,

16 For all three countries: X2(34, N between 1,06S and 1,1(1) 270.53, p<.OOl; CPI ,92;

GFI > ,96; AGE> ,95; lL'vfSEA <

m,

N,~TlON;\L IDENTITY AND ATTlTCDES TOWARDS LY!MIGRANTS 87

4:

J9*H

Bettenrol'ld

if

aU like, .,

-..r-

~~

*f"Betler wlIlltr), Ihilllllll)st -

~

6" u;j2tH

\\11etl \\1"ong

Contlids with

(lnations

l~t11***

Wll}' detll\1(raC}'

works

"

88 JORGE VALA Rcr COSTA-LOP:2S NATIO?'iAL IDENTITY AND AT1TITDES TOWARDS IMMIGRANTS

89

Rather llim: [C'OlINTR\lnatl\)ual

,{i2'n*

I---~--

--J-Rather han; [C'OlINTR\lnatiollal

.6)"'"

HeUer ,yorld if ;dllike.. ---Bettt't..\.YOrid ifalllikeH

~

;"ft';:'+' [ ."j'H

Better tounlly thail lIUl!;! 6~P** Better wunby than mOilt

r--

.1-1-"'"_~g.'l'~

5~\·+4:

SUPPllIt country \\iltll m-Oll_!!I wheum·oll.!!

.-I-I**" -14''*

Conflicts with (l nations l~t

.21*" 31**'

[ - - Wil)'

d~ll()~racy

\\\)rklih

War dl:1110uacy \\w!;:s(\)lItli(t~ wilh 0' natil)lls legit.

h

7)**;~ _~(i*h

[COllNTR\l illfllH!IKt it! tbewoJ!d [COtTN1Rll illfhlfflce in tbe-world -:~**'

6:.)-t:'~1 ECOlwmic arilll'Hmellts

E":OHVIllJr achim.'m~\lts>

'I

L~tHorial ~ttl~~t)·

I+-

45 * UIts sorial secmity .:'6'<+

Fail" and eqmd trenlml!nt of others Fait IUld eqmd trenhnelll of others

presents the while t:K presents the

countries are small but

levels both of nation scores of both nation-the socia-political syslem functioning

COSL\-LOPES N A.TlONAL IDENTlTY AND ATTlTCDES ,\RDS I~jMIG RANTS 91

90

Tahle 3: Patriotism and

Regression 3,5 3 £,5 I N<ltionaiisrr 1.5 PJtr!otJ~i1i 1 0,5

o

GC'!T1:fl'{The next step in the analysIs consisted of correlating these two dimensions of national identity contents with attitudes towards immlo-ratiol1. In order

to do that, we used nationalism and

variahles

fication were considered as control variables

with the dimensions of

tb e pre'l'iotls step, the results of the first regres schooling, the lower the opposition to

identification also

in a that the more

tbe higber the in table 3 tested the impact of in attitudes w\vards immi!:rration. Tbe results revealed that, in line with the

associated with (both at the perception of threat patriotism is associated c ~ '0

z:

CtE

§ ~ w "J ,~ < T'Jotes: ILr. = #control variables; b) Extended model 2003/2004 of Attitudes towards

"

"

l; '-< v -::l ~"

:::: " w N ce

""

N ::.:: :J ;;...., C N"

j

, "'!,

"; Co 00 , ex; *'"

N .""

~i

v 'JO , ,'"

,r) cl "": 0.. "! j( *,

c'"

I' ~ ":r.

,'"

N ,;, +'"

N C ")'"

'i --- + -c N ~ N + + * Ln'"

'"

("-'"

"! b + ro -: "! * '"'"

d -;j .~ ~ ~f

c"'

w,g

,~ OJ; 0"

2: < U Z,

'" * '"'"

+ '0 0.'""

-10 1;'6 Ib. ~ -0*

.2.::g

atp

<005; * Modelll)i!h92

93

."...

JORGE VALli lI"D RLl COSTA-LOPES

with lower opposition to and lower perceptions of threat. In

other words. as more pride is toward the national

less opposition is manifested to considered as threat. Our dissociation between

e\,er, results show that patriotism can facilitate positive attitudes towards

relevant outgroups, Eke This result needs more

in the future. For example, it would be necessary to understand if the association bet\.lieen patriotism and attitudes towards

a lower intolerance or a hir:her tolerance towards

Conclusions

In

this \ve addressed the issue of the extent to which the salience of identification with a countrywards those who do not share that

In this vein, we examined t\1;'O sets of

""j

J( )If",..""

takes on the studies about national

tionalized here as identification with the country minus identification with

Europe), its impact on attitudes towards immigration and exam

ines its role within the relationship between values and attitudes towards

The second set of proposes that the impact of

national identification on attitudes towards depends on which

of national identiD.' is considered.

ied the effect of national \'5. nationalism

on attitudes towards

values and attitudes towards

showed that the higber tbe comparative national

IS, salience of identification with tbe country than with Eu

more negauve the attitudes towards Results

showed also that the impact of values of conservation on attitudes towards is mediated by comparative national identitv: the hiQ:her the

NATIONAL IDENTITY AND A'J'TITCDES TOWARDS Ly!MIGR<~N

to the values of the tbe national

and the more the attitudes.

Our that the impact of universalistic values on attitudes to ..

would be mediated comparative national lUI_HlelLV

was omy vermen with the Swiss sample: in this case, we observed that a unlyersalism leads to a lower comparative identity (i.e. to higher identification with

In Portugal and Poland, universalistic values are associated with a tive attitude towards immigration, but this relationship is not mediated

a higher identification than with the country is dissociated from universalistic values.

This dissociation between and universalism

does not facilitate the ideal demands indeed

solidarity beyond national that future re

set of countries, the values on 'which builds 'within the I;;uropean context. This will allow for a better understanding of the two patterns of responses we ob tamed (Switzerland ,'s. Portugal and

At

the theoretical our results contribute to clarify the impact of on attitudes towards immie.ration bv showine that suchimpact when it overcomes the identifica

category. the identification

with a superordinate category, such as provides an of

"our world". The results we obtained in fact:, a new hypothesis to be considered in future studies: the double identification with the nation

a feeling of n~ntp.-t;

the and a

elusion and openness to "others", even if not Eutope,lt through identification with the nation and identification with the

Asa show that, to understand the impacts of na

tional with other groups, is insufficient to take

into account comparative identity

177 It should be noticed that ESS does not have direct guescions about natlonal and European identj(ication. Moreover. the ISSP wave on National Identity does not have questions on values. The results presented here were only due to collaboration between these specific countries.

94 JORGE VAL~ .A!,-;D RL:r COS'L\-LUPES 95

represents a slgnttlCant empirical advancement in this domain. It is wit101n this context that we propose that the understandimz of

derived from the identification \vith the the meanings associated with national

Meanings of national identity and attitudes towards Immlgr<1ll1

A factorial allowed the identification of two dimen

sions of the meaning of national identity, theorized by several authors Kosterman/Feshbach 1989: but also Staub

With the

from the immi[!ration Dolicy of each associated with

at the symbolic

and so, patriotism is associated with a lower op

and a lower threat \\That factors may

association between patriotism and

\Xle propose the that the in the

fi.111c6oning of the country a feeling of safety tbat

dissociates immigra60n [rom threat. In this case, the other is no as threat and its presence may be seen as a resource. The research presented here on the meanines of national

riotism and and its impact on attitudes towards

are s6mulating to the extent that show the importance of the contents

associated with a of identification to understand the meaning and

the personal and social repercussion of this same identification. In this the diversity of the irlpnriT~1'\r

associated with na60nal we suggest the study of dle of the nature of the nation on attitudes towards

about the nature of the nation, we find two dominant orientations with an impact on the concep tualization of national identity: one orientation that associates national

to an ethnic and genealogical of the nation: and

an-N IDENT1~Y ,IND .A.TTITl:DES TOW1\RDS I?O!1GRM-iTS

other one that associates it I.vith a civic and territorial perspective discussion see Habermas 1994; Smith 1999), The first assumes a

community and its perpetuation through descendancy. National identity

in this case, an "intrinsic" and natural issue based 00 and

cultural roots and common psychological and social characterisLics. The

second construes oational identity as a

associated to a defined territory, and accentuates the common institutions.

Between these two perspectives, some with subtle nu

ances, have been developed, such as the one that proposes tbat national is based on a combination of sub-groups, that are organized

mrougn institutions and civic participation in several processes,

namely processes (Castles/Miller 1

Moreover, it will be important to examine the relationship between d1ese representations of the nature of the natiun and the relations people

maintain with other groups, with immigrants. Our argument is that

to immigration and the perception of immigrants as a threat

will build upon m ethnist and not on the civic. Some of the

questions at the 2003 \vave of the ISSP could help 011 the empirical test of

did not allow to reconstruct those two

conceptions with enough \XTe hope that a new edition of the mod

ule of lSSP on national identity takes on this issue and deepens it, the pioneering work coordinated by Max Haller.

To sum up, this work revealed not only the and complexity of

the concept of national identity, but also the importance of its salience and its contents for a better understanding of attitudes towards immigration

and in a more way, this suggests in order to

understand the of idenrjfication with a group on the relations

with other groups, it is important to know not the of identifi

cation but also the

References

Reuben M./Kenny, David. A. (J "The Moderator·Medlator Variable Distinction in Social

Statistical Considerations",

nationaler Identitat in West· und national ill \Xlestern and Eaotern

1, No. 28: 19-54.

r

96 JORGE VAU\ Ru COSTA N,\TIOl'.o\.L IDEl'TJTY i'lTTlTl"DES TOWARDS IMi>lIGRAN'I'S 9

Daniel "Patriotism as Fundamental Beliefs of Group Members", Feshbach, "Individual National Attachment and t.he

Politics tlnd IlIdilJidualVol. 3: 62. Search for Peace: Psvcholo0cal Persbectives". A.I!{!re.r.ri'Je Bebal)ior VoL 13: 315

Bart/Beerten, Roeland (2003), "!\ational and Atti- 325.

iJl a Multinational State: A Renlication", Political

Peter "National in a United

Nationalism or Patriotism? Empirical Test with Data",

Pn:rh,,/navVol. 24: 289-312.

Lena

"Towards an Interactive Acculturation Model: A Social

Vol. 369-386.

Brewer, B. (1999), "The Psychology of Preiudice: In2toup Love or Out· group Hate?"

Brown, Rupert

.J.

et al. "Recognizing Diversity: Individualist-Col lectivist and Autonomous-Relational Social Orientations and their Ilnpl1catlorlsfor Intergroup Processes", Vol. 31: 327-342.

Brubaker, 28: 1-19.

of iunerican National bhmore, Richard

'''Je ne suis pas raciste,mais ... ': lropeenne. Analyse secondaire de

39-170.

sociaL Dos

CWlJJlit1JJmt, Content, Oxford.

Esses,

tition and Attitudes Toward

Model of Conflict"

Tamara (2001),

Immigrants and Immigration: An Instrumental Vol. 54: 699725.

Structure and Correlates of United States and

Sl11dy", in: Bar Tal Daniel/Staub En-in IL, US: 91-107.

11l11JJifJratiol1 in the Urtiled Sttltes, .Frana: and

Haller, Max (1999), "Voiceless Submission Of Deliberate Choice? and the Relation between National and European Identity",

F"Xllmp.,up

in: I,',n<'hP1cpr et aL Nations and Nationa! Identity. The Etlrobearl

Pprrlwf;'Jp. Chur/Zlirich: 263-269.

'''~'~'''J'L'''.U B.

Nadia National Identity,

Maria/G6mez,

y Identidad Culrural", in: Morales. Francisco Karazawa, .Minoru

Citizens" ,

and Political Involvement", Vol. : 63-77.

Herbert C. (1997), Processes in the Resolution of International Conflicts: from the Israeli·Palestinian Case", A.1JIIJrit"an

Vol. 52: 212-220. 222-241.

sheaf.

Rick/Feshbach, (1989), "Toward a Measure of Patriotic and

PCllchnLnOl! Vol. 10: 257-274.

...

8 JORGE ,\ND Ru COST.\-LOPSS "JilTlON.H IDENTlTY AND ATTlTl:DES TO'VARDS IMM1GRANTS 99

Vol. 7: 90-118.

Olivier "Docs Breed Xeno

Identification as a Predictor of InLOlcrance Toward Immi VoL 12: 115.

00 the Present: Social PolillCS", British of

Identidade nacional [National Lisboa.

"Social Identity does not Maintain that Identifica

tion Produces Bias, and Theory does not Mainta.in that

Saheoce is Identification: Two Comments on iYiUlllllJelllley Klink and Brown", Vol. 40: 173-176.

"Positive Distinctiveness and Social Discrimination:

Pr1l!:hulof"l' V()l. 25: 657-670.

J.

"Natiom,]isl1l and PaUiollsm N?tlon:d Idemiticatlun and Rei ectioll" Bi7tilhSori'1/ P,)'{hoIoPl' V(ll. 40: 1'19-172.

,'\ ttit udcs towards 1'-.0.4: 838-861.

Ramos,

Adc'ances in

, PQliti'il/

"Universals in the Content and Structure of Values: Tests in 20 Countries", in: Zanna, .Mark

IJJwho/DfN Vol. 25, San Diego, C/I..: 1-65.

Schatz, Robert Howard "On Varletles of N a·

tional Attachment: Blind versus Constructive Patriotism", Pulitical PrcclioloP1! Vol. 20: 151-174.

face between Erhnic and National lltt:achmem", P"blzc

61: 103-1033.

Sabral, nacional

l1ff·.SI,,"t:ltlnln, of

f nacionak<mo mana tiationalz:fJ1l in a

e a nacionalismo os pa.ta(11gm'ls of natjons and nationaljsm

,Analise Socia/Vol. 37: 1093-1126.

da identidade Somh, race and nation:

, Analise Social VoL 39: 2SS

Spinner-Halev, E. and Selt~Estcem",

jJp,··,j,pdi"p, on Politics Vol. 1: 515-632.

Staub, Ervin "Blind versus Constructive Patriotism: bededness in

Ervin 213

228.

sociais e mem01;a social: al1d social memory: Vol. 17: 385-405.

in 287 302.

Reeve Thomas F. "Race and Relative

IOO

JORGE Al'D Rn COSTA-LoPESNatio Ervin