Y

Histories of Medicine and Healing in the Indian Ocean'Vlorld: The Medieualand Early Modern Period, Volume One

Edited By Anna'ùØinterbottom and Facil Tesfaye

Histories of Medicine and Healing in tbe

lndian

Ocean'World: The Modern Period, Volume TwoEdited By Anna V/interborrom and Facil Tesfaye

Histories

of

Medicine and

Healing in

the

lndian

Ocean

World

The Modern

Period

Volume Two

Edited by

Ann o

Winterbottom ond

Focil Tesfoye

palgrave

macmilLan

#

HISÏORIES OF MEÞICINE AND HEALINC IN THE IND¡AN OCEAN WORTDSelection and editoriaI content @ Anna W¡nterbottom and Facit Tesfaye 2016

lndividuaI chapters @ their respect¡ve contr¡butors 201 6

Atl rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this

publication may be made without wr¡tten permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transm¡tted savé with written

permission. ln accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs

and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting ümited

copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6-l O

Kirby Street, London EClN 8TS.

Any personwho does any unauthorized act in relation to this pubtication

may be liable to criminal prosecution and civi[ claims for damages.

First published 2016by

PALCRAVE MACMILLAN

The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this

work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and patents Act 1 9Bg.

Patgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmil[an publishers

Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmitts,

Bas¡ngstoke, Hampshire, RC21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a divisíon of NatureAmerica, lnc., One

NewYork Plaza, Suite 4500, NewYork, Ny 1OOO4-1562.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies

and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Hardback ISBN: 978- 1-1 3 7-567 61-1

E-PUB ISBN: 978-1-1 37-56759-8

E-PDF ISBN: 978-1-1 37-56758-1

DOI: 10.1 os7 I 978 1 1 3 7567s8 1

Distribution in the UK, Europe and the rest of the wortd is by palgrave

Macmillano, a division of Macmillan publishers Limited, registered in

Ëngland, company number 785998, of Houndmitts, Basingstoke,

Hampshire Rc21 6XS.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-publication Data

Winterbottom, Anna,

1979-Histories of medicine and healing in the lndian Ocean wortd / Anna

Winterbottom and FaciI Tesf aye.

v.olumes cm.-(Palgrave series in lndian Ocean world studies) lncludes bibliographicaI references and index.

Contents: volume 1. The medieval and early modern period

-volume 2.The modern period

ISBN 978-1-1 37-567 61-1 (hardback : atk. paper)

1. Medicine-lndian Ocean Region-History. 2. Medicine-lndian

Ocean Region. 3. Medicine, Medieval-lndian Ocean Region. 4. Traditionat

medicine-lndian Ocean Region-History. 5.TraditionaI

medicine-lndian Ocean Region.6. Healing-lndian Ocean Region. Z. lndian Ocean

Region-History. L Tesfaye, Facil. ll. Title. R605.W46 2015

615.8'8091824-dc23

2015018001A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

These volumes

ore

dedicotedto

medicol workersoround

the worldList of lllustrations

Acknowledgments

1

Making Medical

ldeologies: IndenturedLabor

inMauritius

Yoshinø

Hurgobin

2

Treating Black Deathsin

Egypt: Clot-Bey,African

Slaves, and the Plague Epidemicof

1834-1835

George Micbael La Rue

3

Rockefeller PublicHealth in Colonial

India ShirishN.

Kauadi4

Colonial

Madness:Community

and Lunacyin

Nineteenth-Century

India

Anouska Bhattacharyya

5

RussianMedical Diplomacy

in

Ethiopia,

1.896-1913 RashedChowdhury

6

Tropical

Disease and theMaking

of

Francein

Réunion Karine Aasgaard Jansen7

Medicine on the Edge: Luso-Asian Encountersin

the Islandof

Chiloane, SofalaCristiana Bastos and

Ana

Cristinø RoqueI

Zigua

Medicine, betweenMountains

and Ocean: People, Performances, and Objectsin

HealingMotion

Jonathan R. Wølz

9

Indian

Ocean'Worlds: Tracing SouthAfrican

"Indigenous

Medicine"

lulie

LaplanteContents

27 6T 89 115 147 1,7't 1,97 1Xxi

'1. 21,9viii

Contents Concluding Rernarks MichaelN.

PearsonBibliography

Contributors

lndex

24s 255 275)77

lllustrations

Figures

1.72 175 1,787.1.

Indian

Ocean map showing Chiloane, Goa, and Macau7.2

Medical

Schoolof

Goa7.3

TheHarbor

and Islandsof

Chiloane(

rrcT-cDI-

0 4 83-1.9 s2)7.4

Excerptfrom

the registrybook of

theplant

samples collected by Ezequiel da Silva

(1883)'

IICT,

AHU,

Códice-SEMU -21, I 67.5

Gynandropsis gynandrag.L

Rastafarian sakmanne photographed duringour visit

of

the medicinal

plant

garden,part of

the Indigenous Knowledge Lead(Health)

Programof

South Africa'sMedical

ResearchCouncii

at theDelft laboratory

facility

in November 2007 1.84 186 35 39 185 234Tables

34 2.1 2.2 L.J 7,7Plague

mortality

inAlexandria,

Egypt,in

the epidemicof

1834-1835

Mortality

rates inAlexandria,

Egypt,in

the plagueepidemic

of

1834-1835

Plague deaths

in

Cairo

in

1835, byethnicityinationality

7

Medicine on

the

Edge:

Luso-Asian

Encounters

in

the

lsland

of

Chiloane,

Sofala

Cristiona Bostos ond Ana Cristino Roque

lntroduction

In this

chapter we

addresscolonial

perceptions

of African botanical

knowledge and healing practices

as expressedin

the

writings of two

different social actors, both

connected

with

the

Portuguese empire

in

the Indian

Ocean,

both

living in

the island

of

Chiloane

(Sofala,

Mozambique)

in

the

1870s:

Arthur

Ignacio da Gama,

a

graduate

of

the

Medical School

of

Goa (India) placed

in

Sofala

in

1,876;and

Ezequiel

da Silva, a third-generâtion

Portuguese

local

teacherwhose ancestors

had

first

movecl

from

Portugal

to

Macau

(China)

and

from

there

to

Mozarnbique.

lØe analyze

their

writings

within

the context

of the shifting

European

imperial politics in Africa

and

within

a large-scalecirculation of

people, things,

elementsof

knowl-edge,

practices, and

experiences acrossthe

Indian

Ocean.They stand

for

distinct

styles

of

circulation through the Indian

Ocean:

Arthur

Ignacio da

Gama

was part

of

a

flow

of

Goan skilled

professionals

who

sought

work

outside Goa and

saw themselves aspart of

aproj-ect

of civilizing

the

world

using moclern standards, European

medi-cine among them; Ezequiel da Silva

belonged

to

the more mobile

group

of

Indian-Ocean-born

Eurodescendants

who

lived close to

local populations

ancl usedlocal knowledge

for

practical

purposes,

I

177

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina RoqueGoan

Physicians

and

Empire

Between

1842

and1961,

hundredsof

young

menand

arnuch

smallernumber

of

women studied

rneclicine,surgery,

or

pharmacy

in

theMedical School

of

Goa.

After

graduation, many

of

them

served in

the

Portuguesecolonial health

servicesin Asia

and

Africa,

in

placeslike

Macau,

in

China, the

easternsection

of

the island

of Timor

nearAustralia, the

CapeVerde islands

in

the

mid Atlantic,

the

SØestAfrica

coast

of

Guinea, or,

in

larger

numlrers,

Angola and

Mozambique

(Figure 7.1 ). Regardless

of what

might

have been thepersonal

motiva-tion

behind

eachof

theindividual

trajectories,

thecollective

endeavorof

Goar-r physicians inAfrica

during

the nineteenthcentury

would

later

be celebrated as a

pillar of

the Portuguese empire.In oral

lore,

in

¡rub-lic

ceremonies,or in print,

Goan doctors were depicted

as thosewho

had

beenout

therewhere

no

one elsewanted

to

be,risking their

livesfor

the

safetyof

the troops

and

for

the noble mission

of treating

theindigenous populations. Rather than products

of

empire, Goan

physi-cians were

presenteclâs

agentsof

empire-building.

Suchviews

weresoiemnly

expressedat the

centennial anniversary celebrations

of

themedical school

in

1942.1Yledicine on

the

Edge

173Given the

political

armosphereof the

1940s,it

isnot surprising

that

the government-appointed directors

of

the school

choseto

cheer, cel-ebrate,and befriend the

Portugueseadminjstration,

prescnt and

past,rather

than criticize it. Indian

nationalism was at its peak, the

British

rule

in the

subcontinent was near

the

end, and Goa was

thcn-after

having

been neglectedto

quasi-irrelevance

through

theeighteenth

andnineteenth

centuries-under

pressure

to

take

advantage

of

its

con-nections

to

Portugal and

keep

away

from

the surrounding

upheav-als.

lØhen India

becamea new nation,

in

1947, Goa

remained

oneodd

"Portuguesepirnple on the

faceof Mother India,"

asin

the

quoteattributecl to Nehru.

Neither diplomac¡ nor

thenationalist

struggleof

the satyagrahas

through the

1950s,or international

pressure, changedthe

stubborn position

of

Salazar's

Portugal;

the annexation

to

theIndian Union

occurred

only in

1,961,, after adisplay

of military

power

followed by

peaceful surrender.

In

1987, Goa

becamea

state

of

theIndian

Union,

after

a

referendum

(the 1967 Opinion Poll)

in

which

Goans showed

their

preferencefor

remaining

asmall

staterather than

merging

with

Maharashtra.2

Back

in

the

1940s,

Goa was

ât

the

crossroads

of

major

changesin

world politics. The

Portugueseadministration

insisted

on

follow-ing

anidiosyncratic path

againstdecolonization

and presentedempire

as an

imagined transcontinental

community in which different

identi-ties

happily

combined

with

one

another

and merged

in

a

single

des-tiny.

Goa was assigned aprominent

role

in that

imagined community.

Goa

wasthe

evidencethat

Westand

Eastcould

meet.Goa

evoked the golden ageof

sea trade, great churches, and heroes like Vasco da Gama and FrancisXavier. Lusotropicalism,

theideological

cementfabricated

in the

1950s and adopted

in the

1960s

by

the

Portuguesejust at

themoment

when the

European empires were collapsing

for

good,

wasyet

to

be available

with

its repertory

of

friendly colonialism and of

Portuguese

easywâys

in

the

tropics.3

In

the

L940s,

the rhetoric of

empire was

still

about

conquest, precedence,braver¡

and thecivilizing

mission. Those were also

the

key

words

in

the

speechesmade

at

thecentennial

of

themedical

school.It

is

not

clear whether

those

who

actually

served

in

the African

health

serviceswere imbued

with

the

senseof

mission

that

was later

attached

to

their

trajectories.

Did

they

chooseserving

in

Africa

andcaring

for

theAfrican

bodies and

souls,or

was

their route

more

of

a contingency?Did

they take sideswith

the Portuguese and feelthat they

were treated

like

equalsin

a sharedmission of

civilizing

by colonizing,

or

were they treated

ascolonial

subjectsand kept

in

secondary roles?On other

occasions, we have addressed theambiguities

experienced byllJI?1-{Ìt 'rt,iiÀl!

. .,-.-f '','"'!. ì'-:

174

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina RoqueGoan

doctors in

Africa.

In this

chapter we readfurther into

thewriting

of

one

of

those doctors,

Arthur Ignacio da

Gama, and compare him

with

hiscontemporary

Ezequiel da Silva.Both

menlived

in

the

islandof

Chiloane

(Sofala)during

the

1870s.4Arthur

Gama:

A

Christian

Brahmin

from

the Goa

Medical School

Arthur Ignacio da

Gama

was born

in

1851 inVerna,

Salcete,into

afamily

of

Christian

Brahmins.

He

attended medical school

in

nearbyPanjim and

graduated

in

1875.5Although we do not know

enoughabout his childhood and

teenageyears

to

assertwh¡

when, and

if

he

wanted

to

become adoctor, we

know that

it

was

achoice

of

elec-tion

among

the

social

group

with

the peculiar

referenceof

Christian

Brahmins, about

whom

somecomment should

be made.Christianized

since

the sixteenth

century,

when

pressured

by

thePortuguese

to

convert

or

otherwise

leavetheir

land-which

somepre-ferred

to

do, and fled

to

the neighboring counties6-many

families

had adopted

the

language,religion, clothing,

architecture, and

tastesof

the Portuguese,while

keepingrelatively intact

their

role

in

thelocal

social

hierarchies.

Christian Brahmins

represented

the upper

crust

of

the accommodation

between

the

European

wâys

and the

caste-evoking

traditional

social hierarchy.

Highly influential in

the Catholic

Church, Brahmins

competed

with

the

Chardo, another prominent,

caste-evoking

group

that wâs influential

in

other

spheres,and with

the small rninority

of

Luso-descendants,who claimed direct

lineagefrom the ruling

Portugueseand

receivedthe highest privileges

in

theadministration.T

Some

Christian Brahmins had long

beenfamiliar

with

medicine,by learning

from their

elders,

from

assisting Portuguese

physiciansand

surgeons

in

the

military

or

religious hospitals,

or

yia

one-on-one

transmission

of

knowledge

by

the

headphysician

in

charge. Theinstitutionalizatíon

of

the

Medical School

of

Goa-which

should

be

credited

to

this group, who provided

the

majority

of

the

student

body-should

be seen as one stepin this

process,râther than

aninitia-tive of

the Portugueseadministration.s Partly

acontinuation of

along

process,

and

partly

arupture with

the pastand

anâttempt

to

endorseEuropean

modernit¡

the

school

allowed no

compromise

with

tradi-tional

medicines(Figure 7.2).Wh,atever

might

have been the students'previous

knowledge

of

local

healing

traditions, they were

supposedto

leayeit

outside the

walls

of

the Maquineses palace, where,

in

theA ¡oss¿ Frcol¡, nåo é o ûiste êdif¡cio plôntôdo i mårgem do M¿ndov,. Náo !åÕ ås iuås divi5ó65 intårnas æbret e monóton¿r, que o c€racterizam E à ruð evÕluçáo lenlð ðås progrêsiva j é a voz dor seus profelrores vieos ou.noilo, que nela tr¿ba

lh¡rôð! trabålh¡m ôihdåt é o ê€o de¡sa¡ vozes que ¡a'ndo de um obscuro cantrnho roam pelo mundo r¡lairo. Ê estê o facho iuminoso que ma¡cå a 5ua existêñc¡ð d! rane ete longo periodo êo meio de de¡rocada dås ånt€as conqu,stås ¿firn,êndo ainda c bendirendo a glóriâ dG uñt îsçåopeq!€ns no seu territónô ós! grande na sðlvé, Escola Médicâ d€ Goa, måe carinhosa qus ¿mbàla¡tos nor vossor braços 6morosor l¿ntor filhor que na ruô pótrið € n¿¡ duar Áft'øs deram o melhor rJo çeu

*forço parr .mpôrô. ¡ vidå d6 tantot pionêios då c¡vrh¡åçåo.

Nirguém * leñbra hoþ dos obscuros ioldados. mâs irso pou€o impotð S€n

ti.d às ondôi ftg¡dorô: do ódro o malquerenga mas falará mais alto seu verd¿de'ro

dorøimento. O facho de glório da Ê¡cola Médica. nåo ôstó nst måos deste nem daqæle ; somo:todos nó¡ os cor¡e<Jores do lucano. alumiando o caminho dc pôssado do pr€sntea dô futuro, .m obo út¡l ê proveito3a À huúùôidad€. Somo: como ¿s

abelhar quo na colmeia fab¡icm em sílêncio o mê|, e nenhuma se arroga o drrerto ¡ p.im¡¡,¡ ¡o tæb¡lho. A glória da Escola MËrtis de Go¡ é ¿ glória dã N¿çáo nelte reñolo O¡ie¡tâ. Ê' o eco do parsado æomodado às atrcuñlànci¿i prè5entes no

ooinho do pÞgc$o.

Eodt¡ ¿ nos¡¡ Ëscoia Médic¡ n¡ ¡ua snb ctu!ôdå I

Woli-ñao d¡ Etlv¡

( Dd Àlocdç¡d profdidâ t{lo Caotcn{íÒ dù llsóla )

ßigure7,2

Medical School of GoaSource: l. Pacheco and D. E. Figueiredo (7960), Escola Médico-Cirurgica de Goa-Esboço

Hi stórico (Bastorá: Tipografi a Rangel)

annex

of

the

military hospital, facing

the

Mandovi

River, the

schoolhad functioned

sinceits

foundationin1"842. Meanwhile, life went

onbeyond

the

school

walls,

and

headphysicians

reported that

studentsand

graduates

were so

immersed

in

local healing

that

they would

rather

usetraditional

medicines

when sick

and, sometilnes, included

them

in their clinical

practice.e\üe

do

not know if

the young

Arthur

Gamahad much exposure

to

traditional

medicinesbefore

heattended medical school.

Síe doknow

Medicine on

the

Edge

175Iseda llúd¡ro-tirúrgi{iâ ds ütra

176

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina Roquethey

were not

encouraged

in

its

all-European

curriculum,

fashioned

after those

of

the

Medical-Surgical

Schools

of

Lisbon and

Porto,

which

had started

in

1836, offering

âmodern, hands-on

training,

asopposed

to

the

old

scholastic

ways

of

the

legendary

University of

Coimbra.

rühether

Arthur

hadhands-on

training

or

satthrough

amore

scho-lastic type

of

teaching

is

debatable.

There

is

evidence

that

studentsobjectecl

to

using

their

hands

in

generaland

in

dissectionsin

particu-lar; faculty

members condescendingly accommodated

themselvesto

the use

of

anatomical models rather than human

corpses,which,

they

claimed, were

in

shortageat

the hospital.l0 Therefore,

it

is

likely that

Arthur did not

haveto perform

dissections aspârt

of

his

schoolwork

routine.

He attended classes lecturedin

Portuguese byPortuguese-born

professors

or

by Goan doctors trained

in

Portugal;

hetook

his

examsin

Portuguese,after studying

French, Portuguese,or

Englishtextbooks,

and

used supplies shippedfrom

Europe. He

learnedwhat

was

learnedin

Europe, and

cameout

of

school

with

a

degreein

European

medi-cine.

Then

hewent on

to Africa.

From Goa

to

Mozambique

Besides

Africa, what

other options were

therefor

the

graduatesof

theMedical

School

of

Goa?Not

that

many.

Someof Arthur's

classmateswould

never evenprâctice medicine;

anumber

of

them

went into

thepublic administration, something

that

a

college

degree-regardless

of

its discipline-helped

make

possible.ll

Opening

a local clinic

washardly viable;

at

the time,

not

even

the higher-ranking

Portuguese-certified

physicians

stationed

in

India could make their living from

the earnings

of

aprivate prâctice.

Theycomplained

that

there wasnot

enough

local

clientelefor their

services,noting that most

peoplewould

rather

goto

traditional

healers, and theonly

clientsfor

Europeanmed-icine were

thefew

Portuguese residentswho felt entitled to

be treatedfor

freeby

their

compatriots.12Entering

a career as arnilitary

physician was a morelikely option

for

the graduates

of

theMedical

Schoolof

Goa,and many

of

them found

that this path

led them

to

distant

locations

in Asia

and

Africa.

Someof

their routes followed preexisting paths and

connections

through

the

Indian

Oceanand

into

theAtlantic, with

Portugal

as one possibledestination,

but

also

including

Bomba¡ the Gulf, and other parts of

the

world

asviable

placesto

settle, serve,come back

from,

and

even-tually go back

to, in

one

or

another's generation.

Thesetrajectories

followed broadly

the routes framed by

EngsengHo for

the

centuries-Yledicine on

the

Edge

177old

spreadof Muslim families throughout the Indian

Ocean,

aswell

as those

recently depicted

in

detail by Pamila Gupta,

SelmaCarvalho,

and

Stella Mascarenhas-Keyes

for

Goan

diasporas

in

Mozambique,

the

Gulf,

and East Africa.13Among

the many routes

acrossthe Indian

Ocean,the

path

to

thecoast

of Mozambique had

beenattracting

generations

of

Goans

and otherpopulations from

thenorthwestern

coast ofIndia.la Mozambique

had

beenunder the jurisdiction

of

Goa

until

the

eighteenth century

and many Goan families

extendedtheir trans-Indian

Oceannetworks

into

the

eastern coastof Africa;

when

JoãoJulião

daSilva referred

to

the

district of

Sofala, helisted

Goans asregular

residents.l5Collating

anumber

of different

sourcesfor

the nineteenth century,

we were able

to identify

40

graduatesof

theMedical

Schoolwho

held

official positions

in

the health

servicesin

Mozambique

(seeâppen-dixT.L).Willingly or unwillingly,

they provided

a steadyworkforce

ata

relatively low

cost

for

the

Portuguesegovernment, given

that their

training

had

mostly

beenself-financed and

their

earnings were

mea-ger.

Goan

graduateswere

kept in

secondarypositions and

could only

progress

in

their

careersif

they went

for further training in

Portugal-which most

did

not.

Many

complained

about

what

they

regardedas

an intrinsically

unfair

system

that

made

them eternal

subalterns,regardless

of

their

quality.l6

Adding insult

to

injur¡

some hadto

work

under

Portuguesesupervisors

who

scornedtheir

medical

degrees andlaced

their

comments

with

anti-Asian

prejudice.lTDespite

thesediffi-culties,

the

idea

that

Goans

would provide the ideal workforce for

the

Portuguesehealth

servicesin Africa

was

first

suggestedby

aGoan

doctor; not just

any doctor,

but

Rafael

Antonio

Pereira (1847-1.91.6),a

Benaulim-born

Christian

Brahmin

who

studiedmedicine

in

Portugal

and returned

to

Goa,where

heattained higher positions and directed

the medical

servicesbetween

1884 and 1893.

At

a time when

theschool was under

siegeand the

Portugueseadministration

consideredclosing its

doors, Rafael Pereira developed anargument about

thespe-cial

qualities

of

Goan doctors

for

the

colonial

services:they were

thebest intermediaries between Europeans and

Africans,

knowledgeable

enough

to

bethe carriers

of

civilization,

and accustomed

to tropical

harshness

and

illnesses.lsThe

sameline

of

argument

was later

pre-sentedto

the

Portugueseparliament

in favour of

the

Medical

Schoolof

Goa-with

success.leYet before Goan physicians were

defined

as thedoctors of

empirein

Africa, their

livesin

the

colonial

outposts were

often random

experi-ences

of

disorder and

improvisation

under

harshconditions

andwith

l7B

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina Roqueown, albeit carrying

a senseof

mission,that

Arthur

Gama actedwhen

he

took

hisposition

Chiloane,

in

1.876,at

theyoung

ageoÍ

25, where

he

would

stayuntil

hispremarure

deathin

1882.Into

the

lsland

of

Chiloane

The capital

of

the Sofala District was transferred

from

the

main-land

port

of

Sofala

to

the Island

of

Chiloane, located nine

leaguessouthward,

in

theyear 1860,

owing to

environmental constraints and

political instability that included warfare and retaliation by African

groups.20

Portuguese

sailors had

been

using the island

as

an

alter-native

to

the mainland

port of

Sofala since

the mid-sixteenth

cen-tur¡

but

there was

no political

or military role

assignedto

the

place(Figure

7.3).

Described

in

the

sourcesas

of

"six

leaguesnorth

andsouth, and the

same eâst

and

west,"21it

was either

presented as

apotentially

welcoming location

for

settlers,with

its

deep and shelteredba¡ well

supplied

with

pastures,fish, wood,

andplant

resources,or

asa

barren

desertwith

no

comparison

to

the

fruitful

land

of

the

conti-nent where people had

their

farms. In

the absenceof

anofficial

census,it

is

believedthat until the

1860s the island was

inhabited

seasonallyby fishermen

or

used âs âsort

of

trade station,

for

transshipment

anddistribution of

goods, bylocal

traders.In

1890, there wereabout

threethousand

peoplein

the place,of which

fifty

were classified âs"white"'

Figure

7.3

The Harbor and Islands of Chiloane (IICT-CDI-0483-19521. (courtesyof the Historical Overseas Archive [AHU] and the Tropical Research Institute [IICT],

Lisbon.)

Medicine on

the

Edge

179there were eight

European-descent"children

of

the land," plus

someLuso-Asian families,

while the majority were drawn from the

indig-enous population.22

\lhen

Arthur

Ignacio

da

Gama was appointed

to

Chiloane, in

1876,he

was estrangedby

what

heconsidered its wilderness, and did

not

abstain

from exhibiting

his

impressionsin

theofficial

report.23 Incontrast

with

Ezequiel

da

Silva'sappreciative depictions

of

the

place (seeinfra),

Gama's

writings

were

all

about disillusionment

with

thelocal lack

of

infrastructure, lack

of

civilization, lack

of

perspectives,and lack

of

viability. He

suggestedthat

the

Portuguese

administra-tion

should

not

insist

on colonizing

the

place,which might better

beleft

to

the clouds

of

insectsthat

emanated

from its

swamps.24In

hisopinion,

therewere more

appropriate

environments

for

settlersin

themainland;

hedid not

referto

the reasonswhy

thecapital

hadmoved

to

the island

in

the

first

place.The

Portuguesewould

indeed move back

to

the mainland

in

duetime;

in

1.892,the capital

of

Sofalawâs

trans-ferred

to

Chiveve,renamed

City of

Beira

in

1907,

which would

havea

notorious

future

asMozambique's

secondcity.

Gamawould not

live

to

seethe new

capital:

hedied

in

1882, succumbing

to

the

feversthat

plagued the

island.Ahead

of

Gama

were the many

tasks

assignedto

colonial

physi-cians.

They

had

to

handle

the patients-mostly

soldiers

and

settlers, asthe indigenous

populations

were

reluctant about

receiving medical

care

from

the Portuguese;2sthey

hadto report

to

their

superiors

in

theMinistry of

Navy

themorbidity

andmortality

figures;

andthey

hadto

provide

aninventory

of

the

causesbehind

thehealth conditions

in

theplace, according

to

the

prevailing

beliefs

on the

influence

of

climate

on

human

health.

Apart

from

these duties,

they

also

had

to

act

asnaturalists

and gather

scientific

data,

samples,and

objects;

they

hadto

observe,collect, and

report on

zoological, botanical, and

mineral-ogical matters. They were required

to

send specimens,plants, grains,

seeds,

and whatever objects

might

beof

interest

to

the

museums andscientific

collections

of

the

kingdom-such

as the

Real

Gabinete

deHistória Natural

daAiuda in

Lisbon, the

institution that

later

evolvedinto

theMuseum

of Natural

History.26People

in

theposition

of

Gama were

pressuredto

compile,

amass,and

report, not just

for

the

sake

of

knowledge

as

a goal,

but

alsobecause

knowledge

was a commodity

in

the

inter-European

compe-tition for

the political and

economic

control

of

Africa. Lisbon

wasa

center

of

knowledge compilation,

with

multiple outsourced

datagâtherers,

but

the

whole

endeavor

did not

match up

to the

ambitious

claims held

by Portuguesegovernments

for Africa. Colonial

officers

in

I

IlB0

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina Roquethe

field

wererequired

to

helpfill

the gaps.Explorers

sponsored by theGeographical Society

had the

mandate

to

map river

sources,moun-tains, and

potential

mines.27 Practicing physicians hadto compile local

knowledge

on plants

and

remedies.In

a

booklet clearly

madefor

thepurpose

of

inter-European competition, Joaquim

Almeida

Cunha,

anofficer

of

the colonial administration

in

Mozambique,

gathered

theknowledge on medical plants that had

beencompiled

in

thefirst

placeby

Ezequiel da Silvain

Chiloane.28Arthur

Ignacio da

Gama

did not show

much personal interest

in

the

medical

usesof

local plants.

Hewrote

thereport

using secondhandknowledge,

for,

heclaimed,

hecould

not afford

the

time to

go

out in

the

field to

collect data when

he was needed as adoctor in what

wasoften

alife-and-death

struggle.He

wasneither

eâgerto

survey,collect,

and

report on

the minerals,

flora,

and fauna,

nor to know

the

indig-enous peoples close

enough

to

report their

lifestyles

and ship their

artifâcts into

somedistant

Etrropean destination;

hewas

not

trained

as a

knowledge-collector,

but

as adoctor,

who did not

rrade

his place at thepatient's

bedsidefor

theoutdoors, wandering

for

bits

and piecesthat might,

or might not,

berelevant

for

humankind.2eFor

someonewho

was sononchalant about

datacollecting,

Gama'sdepiction

of

the healing

rituals

practiced by

theindigenous

peoplesof

Chiloane

isimpressive-making it

asort

of

ethnomedical narrative all

too similar

to

those

produced

in

the twentieth

century.

He

depictedthe role

of

the "inhamessoro"

(nyamasoro),

the

people's

quest for

hís

or

her

services,the

sort of afflictions

they

brought

to

the

healers,the worldview they

espoused,the

instruments,

gestures, dress code,sounds, smokes, substances,

and

other material

elementsinvolved in

diagnosis

and treatment.

He

also made anattempt

to attribute

mean-ing to all

thesethings.

His

prejudice, though, was parenr

all through

the

narration.

Gamacould not

helpbut

formally

distancehimself

from

traditional

healing, perhaps as agood

child of

hisalma

mater, perhapsas someone

who

hadto

always emphasize, morethan

otherswho took

it for

granted,

his Europeaness and hiscommitment

to civilization

andscience.

Trying

to

be objective,

yet

unsympathetic, Gama displayed

hisprejudice

against

African islanders'

lifestyles,

which he

regarded

asmarked

by

a

negligent attitude

of

living

for

the moment,

founded

upon

what

we

would

refer

to

today

as genderinequities: women

hadto perform

all

the

hard

labor, and men

measuredtheir wealth

by

thenumber

of

wives

they

controlled.3OGama's

opinions

seemro

accordwith

the

establishedviews about Africans held by

Portuguese settlers,lYedicine on

the

Edge

lBladministrators, and missiolaries.

\íhat

stands

out

in

his writings

isthat

despite his distanceand disdain

for

empirical

work,

heprovides

adetailed, ethnographic-like account

of African

healing.

Could

he haveobtained

it

from

Ezequiel

da Silva,who

was

soimmersed

in

the local

life to

thepoint

of

being depicted as a Ganga, the"halfway

witch-doc-tor,"

by the

officer

Cunha

in

1883?Or

perhapsfrom

Cunha

himself?With no

record

of their interaction, we

can

only

guessby

comparing

their

writings-and

conclude

that

Gama's

depiction

is

a much

more

diluted and

impressionist approach

to

local

knowledge

than

that of

Ezequiel,

who

wasfully

immersedin

local culture.

Plants, Healing,

and Knowledge

It

is unlikely that

in

such

a small

place as Chiloane

Arthur

Ignacio

da

Gama and Ezequiel

da

Silva never met,

asboth

were

part

of

theinner circle

of thoseupon

whom

the Portugueseauthorities relied' The

Portuguese

community living in

Sofala hadalways

beenquite

small.'11 Peoplefrom

Portugal (reinóis) were very

few

and most

of

thosewho

qualified

as Portuguesehad

first

gone

to

India or Macau

before

set-tling

in

Sofala. There

were also convicts

or

prisoners,

who did

not

represent

mainstream European culture.

In

other words,

the

local

Portuguese

community

wassociall¡

culturall¡

andhistorically

distant

from

Europe; theymight

rather

be regarded asbelonging

to

theIndian

Ocean'Vlorld

(IO\ø). Unlike

Gama,who

had comefrom India

imbued

with

a senseof

mission

about

rescuingand

"civilizing"

Africans,

peo-ple

like

Ezequiel

did not

feel

obliged

to follow

any external

agendaregarding

theindigenous

peoples-in

fact,

Ezequiel andhis folks

were regardedby

the Portugueseauthorities

ashalfway

nativeswho

sharedmuch

of

the lifestyle

of

the actual indigenous

population.

Ezequiel was

the

son

of

Zacarias

Herculano da

Silva,

who

began his career as amilitary

man

in

Sofala

in

1810.

His

grandfathers were

João

Julião

da Silva, a second-generation Portuguesewho

wasborn in

Macau in1769

and movedto

Sofalain

1'790, and FranciscoHonorato

da

Costa,

who

in

the early

níneteenth

century had

beendirector of

the

"Cassangefair,"

atrading

post

in the

Cuango,

Angola.

Ezequiel'sfamily

was closely connected

to

the

Portuguesecolonial

administra-tion, like many

others;

unlike many

others, however,

was their

pro-found

knowledge

of Africa

and

of

the

experienceof

the IO\ü. Joining

the

Portugueseadministration at

ayoung

age,Ezequiel da Silva

took

the

position

of

schoolteacherin

Chiloane. He

was

aheady therewhen

l82

Cristiana Bastos and Ana Cristina RoqueBesides

their

differences

in

social background

and

education,

Ignacio and Ezequiel had different worldviews and different

atti-tudes

about the

place

they were

in

and the

people

who lived

there.Ignacio

was âpasserby; Ezequiel was

aresident.

Ignacio

wasan

out-side observer; Ezequiel

was part

of

the community.

Those

different

positions are apparent

in

the ways they

observe

and

describe

theisland

of

Chiloane, its

characteristics, resources,

and potentialities.

The

worthless,

unsuitable island

described

by Ignacio is referred to

by

Ezequiel da Silva as

a

complex

ecosystem,providing

different

resources

that local

people

knew how

to

useand capitalize

upon.32Unlike

Ignacio's, Ezequiel's observations were the

direct

result

of

hisown knowledge

of

the region. He combined observation and

living

experier-rce

in

acontinuous

learning

processlegitimized by local

tra-ditional

usesand practices. Therefore

he was ableto look

far

beyond

the

"poor

lanclsof

Chiloane,"

identifying

resources

and

potentiali-ties,

namel¡ medicinal

herbs

and plants that,

once analyzed,

could

come

to

integrate the

Western

pharmacopoeia and be

a

source

of

income

for

the

colony.33Informing

on thedifferent medicinal

herbs andplants existing in

theisland

of

Chiloane,

Ezequiel da Silvaprovides

dataon

thelocal

ecosys-tem and specificdifferent habitats-sandy

lands, sandydry

lands,wet-lands,

sandywetlands, mangroves,

beaches,and coastal

lagoons-all

of

them testifying

to

the island's

biodiversity

and his

own

knowledge

on

the

territory. For this

reasonCunha

refersto him

asa

Ganga, the

"graduate

healer,"

the

one

to

beconsulted whenever the

community

had a health

or

apolitical

problem.3a \ü/heninforming on traditional

knowledge

andpractices related

to

theknowledge,

identification,

and useof

medicinal

flora,

Ezequiel showshow

he wasân insider

to

local

culture. Moreover,

he suppliesadditional information

on theway

peo-ple

exploit

and manage thelocal natural

resources.This "being

part of

the

group"

became essentialeither

to report

usesand

prove its

effec-tiveness

or to

substantiate

traditional

knowledge.

As

a physician

and having to

face the

many difficulties

related

to

the

operability

and effectivenessof

thehealth

servícesin Mozambique

(lack

of

funds

to

guarantee

basicoperating

services,lack of

facilities,

lack

of

human and technical

resources,and

lack of

medicines), Gama gavepriority

to clinical

observations,

seekingto

act according

to

hisscientific background

and neglecting â moreempirical approach to

thelocal medical solutions. This approach

would

haverequired long-term

research,

for which

he

had no time

to

spareand was

not

convinced

would

beworthwhile.

35Medicine on

the

Edge

lB3Thus,

although both Ignacio

and Ezequiellooked

into

theproblems

of

disease and healing,their

perspectives wererather different. Ignacio

advocated

the

defenseof

scientific medicine

and its role

asa

vector

of

civilization; whether

or

not

he might be personally

sympathetic

to

traditional

healing,

or

even exposed

to

it

outside medical

school,his formal training was

all

about rejecting the argument that

non-European knowledge

might

bevalual'rle

and

effective;

for

him, only

European

medicineshould

besupported,

used, andpromoted.

In

sucha

corner

of

the

world,

with

so

many

adversaries,he

might

have

felt

that

histask

was immenseand

perhaps he wasalone

as thepaladin of

scientific

medicine.Unlike lgnacio,

Ezequiel waswell

âwareof

hislack

of "scientific training" in

medicine;

on

the

other

hand,

he hacl apro-found

knowledge

of

the place,its

resources, and the usespeople

madeof

them-particularly

in

the

field

of

herbal medicine.

He

stressed theimportance of making a rigorotts and

systematic survey

of

the

local

medicinal-pharmaceutical flora, which

recluiredlearning about

its usesfrom

the local

practitioners;

the results

of

such research, he foresaw,would

have animpact

not only in

Sofala andMozambique but

alsoin

the

other

Portuguese overseasterritories

and

evenin

Europe.36This particular position

of

Ezequiel

doesnot

mean he completely

supported

the healing practicesperformed

by thelocal

healers.In fact,

though he

understood

the role

of

the

healers

in

the

communit¡

hewas very critical

of

their performance and

even

doubted

that

their

prâctices

could

beaptly

namedmedicine, although

hereferred to them

as

"Kaffir

medicine."37He

distinguished

clearly

between

the

healer'sperformance

and thehealing properties of certain plants when applied

to practical

situations.

He

regarded

the

healers' procedureswith

sus-picion;

only

in

a very few situations

did

he consider

the

efficacy

of

the

way

the

healer acted.As

for

the

medicines used,they were

worth

considering

becausethey proved

to

be effective.3s 'SØhilepointing

out

the lack

of

a

pharmacopoeia

in

the

Slesternsense and the

difficulty

of compiling

recipesin

the absenceof

preestab-lished

doses, Ezequiel'swork

combined modern scientific methods

of

registry

andcollection

of

samplesfor

study (Figure

7.4

andTable

7.1')with traditional

proceduresof

diagnosisand

treatment.3eEzequiel's

work

revealsa profound

knowledge

of

Sofala'snatural

environment and

of

the

local

phytotherapeutic practices

basedon

theperceived

relationship

between

disease,plant, and habitat

of

occur-rence.His

aim was

to identify

possible solutions

for

health problems

both in

Sofala andin other

regionsunder

Portugueserule.

He collectedi.,

l84

CristianaBafos

and AnaCrilina

Roque/,,!//t ¿ ,/n/

'/ t'/e/ia

Table

7.1

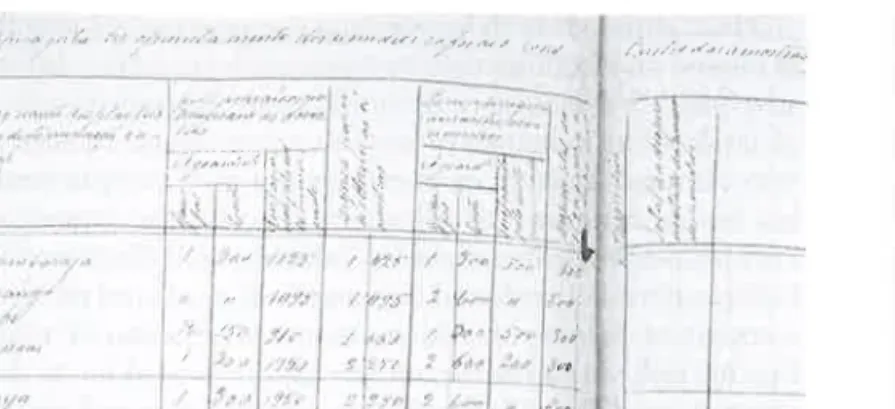

Registry table fo¡ the collected samples. Reproduction of the table usedby Ezequiel da Silva for the registry of the medicinal herbs and plants collected (AHU Manuscript, fl.8v-9)

Number of plants providing these samples 3

.: i (t ,l .1 /.";,,:ì..jI \

ì

t /t.1.|,, .r/,. ' /)¿, ./ it 1J,

,7¿" Root Leave Resin Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces C)ctâves 1\

/.J /' '.t / Bark Designation of the speciesof the several samples

and weight

Figure

7.4

Excerpt from the registry book of the plant samples collected by Ezequielda Silva (1883),

IICI

AHU, Códice-SEMU_2186. (courtesy of the Historical OverseasArchive [AHU] and the Tropical Research Institute [ICT], Lisbon.)

used

in

Chiloane and

SofalaDistrict,

and compiled the

different

reci-pes

listed

in

1883 by Cunha

in

his

booklet.a0As often

acknowledged,

"one could

take considerable

advantagesfrom

the

useof

most

of

thesemedici¡ss"-¿¡d

thus

headvocated

theuse

of

the local medicinal

flora

and its study (including both plant

potentialities and

habitat of

occurrence), assumingthat

certain health

problems,

in

other regions,

could

beavoided

with

the

introduction of

specific

medicinal plants

that did not grow nâturally

there.alEzequiel

illustrated

thispoint

with

the cases ofDurura,

Chicarafunda,

Gambacamba,

andMutiuari.

Durura

andChicarafunda,

if

introduced

into

regionswith similar

habitats, could provide possible solutions to

decrease

the

neonatal

mortality

rate.

That could

be

the

casefor

theInhambane

District

(south

of

Sofala),noted

Ezequiel,who knew that

none

of

those

plants were growing

there

either

becausehe had

theopportunity

to

gothere

or

because he had agood

informant

on

rhosematters.42

As

for

Gambacamba and

Mutiuari,

introducing them

to

other

areas

could

provide

good local

substitutesfor

the marshmallow roots

(Abhaea

officinalis)

and the extract

of liquorice (Glycyrrhiza

glabra),

thereby

minimizing

theconstant failures of

these drugsin

thepharma-cies

of

hospitals and health

care centers.Knowing

the

diversity

and specificity

of

eachhabitat

and the way

it

influences

the

occurrence

or

absenceof

certain

speciesand,

con-sequently,

the fact that they are

used

there

or

not, Silva

underlines

that the

useof

each

plânt

for

the treatment

of

a

specific

disease isLocal name Goche

Type and

habitat

Trailer with long and rough leaves living in sandy areasAreas of

ocurrence

Chilluane Island and SofalaQuantities used Root Bark Leave Resin Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces Octaves Pounds Ounces Octaves

Medicinal

vi¡tues

Fevers, marsh-fevers, and urinary problems Preparation andapplication

Decoction of the leaves, branches, and roots. Drink hot for

the fevers and cold for the urinary problems

Efficient ¡esults in both cases though it seems that it is not relevant the fact it is taken hot o¡ cold. The reason I mention this is because I was told these were the right procedures accordingly to each disease.

l86

CristianaBafos

and Ana Cristina Roquean important

part of

the cultural

heritage

of

each

communit¡

thusrevealing

both

asolid knowledge of

thelocal natural

resources and the capacityof

usingthem to

solvetheir

basic needs.a3This explained how,

in

asmall island

such asChiloane,

theinhabitants

of

the

sandy landsknew that

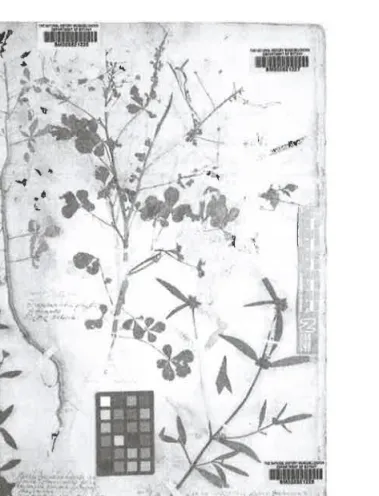

the leaves andflowers oÍ Muanga (Gynandropsis gynandra)

(Figure 7.5)

would

heal

fevers associatedwith

colds,

while

those

liv-ing

in

the mangrovesof

the

sameisland, where Muanga do

not

occur,knew

that Mutungumuja

leaveswould

cure the same symptoms.a4lYedicine on

the

Edge

lB7All

these referencesunderline what

is

common knowledge

basedon life

experience and

traditional

use,complementing the more

spe-cific

know-how

of

the

traditional

healei

that no

community

candecline,

with

that

of

each

specific habitat,

so

that

people

find

dif-ferent solutions

to

solve

trivial

daily problems always

in

view of

preserving

their

balance and welfare as

a

community. Just as in

Paracelsus's

saying

that

"each

country

has specific

diseases

andfor

each country

nature provide[s]

the

solution

to

heal

them,"46Ezequiel's

findings reveal different types

of

herbs and plants

with

medicinal

virtues-in

wetlands, salt-marshy

areas,

dried,

or

sandy

lands.

These

herbs were applied

to

solve

or

slow down the

most

common

ailments and

diseases.Concluding

Note

In

brief,

in

the context

of

establishing the

Portuguese

colonial rule

in

Mozambique

there

is

evidence

that

many

âctors-Africans,

Europeans,

Luso-Africans, and Luso-Asians-were involved

in

dif-ferent forms

of

knowledge

exchanges, someof

them

with

therapeu-tic

value. The

brief

analysis

of

two

different colonial actors who

lived at

the

sametime in

the island

of

Chiloane, Sofala, and referred

to

local knowledge

of

plants and healing

practices,

show

that

thescope

of

interactions

acrossthe

Indian

Ocean ismultisided,

complex,

and irreducible

to

a monolithic understanding

of

the relationship

between colonizers

and colonized, foreigners and

locals,

and

exter-nal

and indigenous knowledge.

Arthur

Ignacio

da

Gama

went

to

Mozambique like many

of

his

Goan

peers-a

colonial

subject

born

into a local

elite, achieved

higher education

in

Goa,

and started

hiscareer

in colonial

medicine by serving

in Africa.

In

Africa

he enactedEuropeanness

and

expressed

reservations regarding

the

lifestyles

of

local populations,

their

healing practices, and

their

knowledge

about

them-ât

least, those

that

he

got

to

partially know.

Ezequiel

da Silva,

on

the

other

hand, was

athird-generation

Eurodescendant

whose grandparents had

beencrossing the

Indian

Oceanand serving

the

empire

in

severallocations. He lived

closer

to

local populations

and adopted much

of

their knowledge-particularly

in

matters

of

potentially

healing plants,

which

hecompiled

carefully. Ezequiel

hadno higher training, yet

he

usedhis skills

and

proximity

to the

local

population

to gather knowledge

andmake

it

available

to

thecolonial

and

European circles,

which

used

them

in

ways

that

areyet

to

beknown in detail

and

deservefurther

research.-ffiffi

$

t

? I¡

"ffiffi

L*t

Þ ,é.t

,'.ff 'E. ì¡hç

t/ -i I I i{Þ

I

I Ì,:\ì

"4,l! T(

IÅ

¡"ffiffiì

{'

I .1 ¡ J Irümffiur

Figure 7..5 Gynandropsis gynandra

Source: Hermann Herbarium, Natural History Museun, London

![Figure 7.3 The Harbor and Islands of Chiloane (IICT-CDI-0483-19521. (courtesy of the Historical Overseas Archive [AHU] and the Tropical Research Institute [IICT], Lisbon.)](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok_br/19292002.993507/9.1262.157.601.532.797/islands-chiloane-courtesy-historical-overseas-tropical-research-institute.webp)