Discussing impact assessment on creative tourism:

A theoretical and analytical model

Elisabete Tomaz

Pedro Costa

Maria Assunção Gato

Ana Rita Cruz

Margarida Perestrelo

Setembro de 2020

WP n.º 2020/05

DOCUMENTO DE TRABALHO WORKING PAPER

Discussing impact assessment on creative tourism:

A theoretical and analytical model

Elisabete Tomaz*

Pedro Costa

Maria Assunção Gato

Ana Rita Cruz

Margarida Perestrelo

WP n. º 2020/05 DOI: 10.15847/dinamiacet-iul.wp.2020.05

1. INTRODUCTION ... 3

2. REVIEWING KEY IMPACT ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORKS ... 5

3. SUSTAINABILITY IN TOURISM IMPACT ASSESSMENT ... 8

4. ANALYSING CREATIVE TOURISM AND ITS IMPACTS ... 10

5. AN IMPACT ASSESSMENT MODEL FOR SUSTAINABLE CREATIVE TOURISM PROJECTS ... 13

6. CONCLUSIONS ... 17

REFERENCES ... 18

Discussing impact assessment on creative tourism:

A theoretical and analytical model

Abstract

Over the last decades, tourism has experienced exponential growth, expansion and diversification, being considered one of the most important socio-economic sectors, an essential source of income and employment for many territories (e.g. Bellini et al. 2017; Romão and Nijkamp 2017; Weidenfeld 2018). In response to the concerns about the negative impacts of tourism and to improve the relationship between hosts and tourists, culture-based creativity is seen as a path to create competitive advantages and improve more sustainable practices in the tourism field. Therefore, many cities and regions have sought to reinvent themselves as creative tourist destinations, by encouraging synergies between tourism and the cultural and creative activities to foster the development of new products, experiences and markets (Delisle and Jolin 2007; Duxbury and Richards 2019; Richards and Wilson 2007).

Despite the high attractiveness of large capitals and metropolises, small towns and rural areas can also benefit from the growth of tourist flows and the demand for less overcrowded tourist destinations. Alternatively, they can offer interactive, small-scale, unique and tailor-made experiences based on local culture, lifestyles, and values thus generating potential positive impacts on these communities (Richards and Duif 2018; Wisansing and Vongvisitsin 2019). In the discussion of tourism development models, sustainability has become an unavoidable frame of reference, introducing cultural, social and environmental concerns, in addition to the analysis of economic issues. In this vein, we consider the integration of culture as a fundamental dimension of the analysis, together and in interrelation with the economic, social and environmental dimensions. Although the impact assessment exercises have focused on predominantly economic indicators, there is an increasing number of methods that can determine and monitor more accurately the multiple links and impacts of tourist activities in local communities, and also address sustainability issues.

This paper has the objective of review the main theoretical and methodological approaches about impact assessment, to develop a comprehensive and operational framework capable of contributing to a better understanding the multifaced nature of creative tourism and their diverse impacts to support the formulation of policies for the sector and according to each context.

Keywords

Impact assessment; creative tourism; small cities; sustainable

JEL classification – D04 Microeconomic Policy: Formulation, Implementation, and Evaluation;

Z32 Tourism and Development

1. INTRODUCTION

Since the 1950s, there has been a steady growth in international tourist flows and the emergence of new tourist destinations (UNWTO 2017b; Schwab, Sala i Martin, and World Economic Forum 2016), accompanied by increasing criticism about the undesirable effects of tourism development, as the excessive massification, commercial exploitation and environmental damage of places or the disrespect for socio-cultural values and daily lives of host communities, among others. Consequently, new ideas and models have emerged in tourism literature under different labels such as ecotourism, cultural, sustainable, adventure, among other types (e.g. Holden 1984; Holden 2005; Cohen 1987; Sharpley 2002; Hall 2010; Pearce 1992; Lertcharoenchoke 1999; Eadington and Smith 1992).

The search for new tourism models also arises following the debate on the paradigm shift on development models: from modernisation theories, focused predominantly on economic growth, to a conception of development that seeks to balance economic, environmental, and social aspects to ensure its long-term sustainability (as discussed, for example, in Sharpley 2000; Sharpley and Telfer 2008; Dehoorne et al. 2014; Shaw and Sykes 2004; Hunter 1997; Hardy, Beeton, and Pearson 2002). The concept of sustainable development, popularised with the Brundtland Report (WCED 1987), and later confirmed as a guiding principle of international policy in the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development’s Rio Declaration (UN 1992), extended to different areas of research.

The first World Conference on Sustainable Tourism, with the adoption of the Lanzarote Charter for Sustainable Tourism (UNWTO 1995), in conjunction with the Agenda 21 for the Travel and Tourism Industry (WTTC, WTO, and Earth Council 1995) launched the discussion about tourism ecologically responsible, economically viable,

socially equitable for local communities and future generations (about the concept see, e.g., Fayos‑Solà 2015; Balas and Strasdas 2019). The World Tourism Organization (WTO) underlines the principal factors to designate sustainable tourism:

1) Make optimal use of environmental resources that constitute a key element in tourism development, maintaining essential ecological processes and helping to conserve natural heritage and biodiversity.

2) Respect the socio-cultural authenticity of host communities, conserve their built and living cultural heritage and traditional values, and contribute to inter-cultural understanding and tolerance.

3) Ensure viable, long-term economic operations, providing socio-economic benefits to all stakeholders that are fairly distributed, including stable employment and income-earning opportunities and social services to host communities, and contributing to poverty alleviation (UNEP and WTO 2005).

These new understandings required an adaptation of the methods of impact assessment to examine and communicate the causal link between the effects generated and the desired results, considering the available resources. Thus, it imposes a variety of questions regarding the formulated intentions, such as what kind of effects it produces, for whom, when, as well as how to measure them.

Despite the wide-ranging debate on impact assessment and various attempts to operationalise it, many issues remain unresolved not responding to the complexity of reality, the multidimensionality, multiplicity and time-range of impacts and specificity of each situation.

In creative tourism research, few studies try to systematically evaluate the multifaceted nature of these activities and their effects in local territories and communities according to sustainability criteria (Buaban 2016; Korez-Vide 2013a, 2013b; Qiu et al. 2019), which is part of their foundations. Furthermore, the adoption of a sustainability framework in the impact assessment processes in this field implies integrating culture alongside and interconnected with the economic, social and environmental dimensions to assess the multiple impacts of creative tourism accordingly each context and the type of experience.

The model here proposed was applied experimentally during the CREATOUR project allowing to perceive challenges, opportunities and constraints in the diversity of

situations found in pilot experiences of creative tourism in the particular context of small cities and rural areas.

2. REVIEWING KEY IMPACT ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORKS

In the last few decades, the literature on impact assessment has broadened in search of evidence to decision-making processes and hence to improve the accountability, innovation and learning of a particular project, program or policy (Gertler et al. 2016).

Several organisations have established their methodologies according to their priorities1. For example, the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) and Social Impact Assessment (SIA) are two systems established since the 1970s that have been employed in various countries to evaluate the consequences of specific actions on the physical environment and societies, respectively. Other approaches have been developed, among which stand out for their widespread acceptance since the 1990s, a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) (CEC 2001b; OECD 2006; Fischer 2007) and the Regulatory Impact Assessment (RIA) (OECD 1997, 2009)2. The first introduces environmental considerations at early phases of the decision-making process of policies, plans and programs, and the second considers the regulatory framework of the nation or region in which it is applied. In turn, the World Bank launched the “Development Impact Assessment Initiative” (2005) to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness of its development programs systematically.

At European level, this interest in impact assessment has increased especially after the work produced for the European Spatial Development Perspective (CEC 1999) and the White Paper on European Governance (CEC 2001a) to evaluate the impacts of EU policies and establish better regulation standards. In 2002, the EU introduced an integrated Impact Assessment model to aid to decision-making (EC 2002b) and the ESPON programme took the task of developing the Territorial Impact Assessment (TIA) method for an integrated analysis of the economic, social and environmental impacts in territorial development. Subsequently, the European Commission published guidelines to

1 For a variety of resources about impact assessment see

https://www.iaia.org/reference-and-guidance-documents.php

2 A review of documents on RIA produced by the OECD is available on http://www.oecd.org/regreform/regulatory-policy/ria.htm

conduct the impact assessment process (EC 2002a, 2005, 2009) and to provide better evidence-base on policy options in line with EU principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.

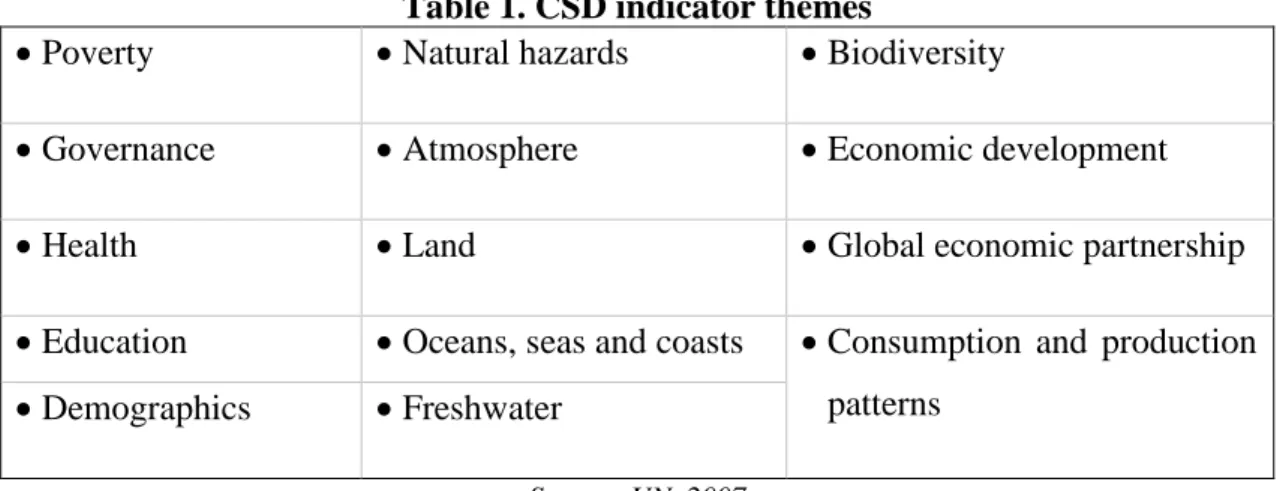

With the dissemination of the concept of sustainable development, several initiatives have been undertaken by international organisations to introduce sustainability principles in assessment processes. For example, in response to the 1992 Earth Summit and Agenda 21 appeals, the United Nation’s Commission on Sustainable Development (CSD) proposed in 1996 a qualitative and quantitative analysis based on a list of indicators and corresponding methodology sheets. The CSD Indicators of Sustainable Development have been tested and adopted in many countries as a basis for the development of their national indicator system. The first editions3 were organised into three primary domains: economic, environmental and institutional. This division has disappeared in the latest CDS revision (UN 2007) which set of 50 core indicators on sustainable development cross-14 cutting themes that are relevant and can be calculated in most countries, in a more extensive set of 96 sustainable development indicators (Table 1).

Table 1. CSD indicator themes

• Poverty • Natural hazards • Biodiversity

• Governance • Atmosphere • Economic development

• Health • Land • Global economic partnership

• Education • Oceans, seas and coasts • Consumption and production patterns

• Demographics • Freshwater

Source: UN, 2007

The OECD has also looked beyond economic growth to establish a framework capable of guiding member states on how to measure sustainable development. They worked on a collection of indicators that reflect the links between economic, social and environmental dimensions of sustainability and their interactions from which relevant indicators can be chosen and reported (see, for example, OECD 2004, 2000). To inform decision making and strategic planning in public investment projects, the so-called

3 “Indicators of Sustainable Development: Framework and Methodologies” (UN 1996) and “Indicators of

Sustainability Impact Assessment (SIA) focused on exposing the long-term multi-dimensional implications of policies, strategic plans and programs throughout the entire policy cycle (OECD 2016, 2010).

The European Union launched in 2001 the first Sustainable Development Strategy, which was renewed in 2006. It intended “to achieve continuous improvement of quality of life both for current and for future generations, through the creation of sustainable communities able to manage and use resources efficiently and to tap the ecological and social innovation potential of the economy, ensuring prosperity, environmental protection and social cohesion”4. To operationalise this vision, a Statistical Program Committee (chaired by Eurostat) developed a task-force to establish a system for Development Indicators (SDIs)5. The first monitoring report was published by Eurostat in 2005, based on the work of the SDIs Working Group. Revised in 2007, it now includes 122 indicators, as well as 11 contextual indicators to describe progress in the EU Sustainable Development Strategy.

In addition to international organisations, many countries and institutions have developed different approaches, models and monitoring tools that reflect the principles of sustainability (e.g. Sala, Ciuffo, and Nijkamp 2015; Singh et al. 2009; Waas et al. 2014; Gasparatos 2010; Bond and Morrison-Saunders 2011; OECD 2008).

More recently, the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were adopted by all United Nations Member States in 2015 to address global environmental, political and economic challenges. These have given rise to a set of SDGs indicators to be used in national statistical systems6.

Another contribution to our debate is the UNESCO Culture for Development Indicators (CDIS). It proposed a method to improve the data and knowledge about the multi-dimensional interdependencies between culture and development. This holistic

4 Council of the EU, Review of the EU sustainable development strategy, document 10117/06 of 9 June

2006.

5 Eurostat had already participated in the test of the initial set of indicators of the UN Commission for

Sustainable Development and based on these produced in 1996 and 2001 pilot studies.

6 United Nations Statistics Division “E-Handbook on Sustainable Development Goals Indicators” https://unstats.un.org/wiki/display/SDGeHandbook/Home. The Eurostat also developed a indicator set for regular monitoring of progress towards the SDGs in an EU context

approach established 22 core indicators that covered seven interrelated policy dimensions:

1) economy; 2) education; 3) governance; 4) social participation; 5) gender equality; 6) communication; and 7) heritage.

Despite the vast literature and the growing number of conceptual models for impact assessment, there are some issues and effects that remain invisible and that are not taken into account in evaluation practices. Moreover, the used instruments tend to focus on short-term impacts and quantitative indicators, provided with easily achieved data. Thus, not responding to the complexity of reality, the multidimensionality, multiplicity and time-range of impacts and specificity of the situations to be monitored.

3. SUSTAINABILITY IN TOURISM IMPACT ASSESSMENT

Research on tourism impacts has focused predominantly on the economic dimension as an examination of the connection between tourism development and economic growth, employment, productivity, expenditure using different methods, such as input-output models, cost-benefit analysis, Tourism Satellite Accounts, etc. (Stynes 1997; Tyrrell and Johnston 2006; Vellas 2011; Frechtling 2013; Pablo-Romero and Molina 2013; Figini 2019, among others).

However, in recent decades, the growing role of tourism and new understandings in this field have fostered the need to observe and consider sensitive and responsible environmental and socio-cultural practices, not just the economic effects of tourism activities, thus introducing the principles of sustainability as a key reference framework.

Consequently, the promotion of sustainable tourism models has led to a need to develop evaluation methods that reflect this integrated vision. Thus, the tourism impact assessment process should be able to determine and move more accurately the multiple current and future connections and impacts of tourism activities, developing a set of indicators that reflect the objectives of sustainability in the development of tourism (Ko 2003; 2005; Cernat and Gourdon 2007; McCool and Moisey 2008; Blancas et al. 2010; Torres-Delgado and Saarinen 2014; Torres-Delgado and Palomeque 2014; Asmelash and Kumar 2019, etc.).

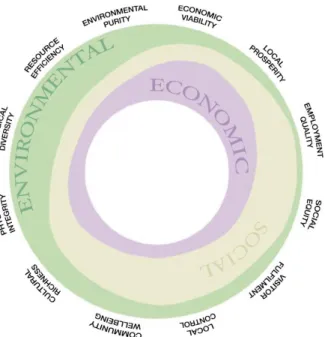

In this vein, international organisations such as the World Tourism Organization (WTO) published a series of technical and manual guidelines since the 1990s to promote the use of sustainable indicators in tourism (WTO 2004). In 2005, the WTO and the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) defined the concept of sustainable tourism as “tourism that takes full account of its current and future economic, social and environmental impacts, addressing the needs of visitors, the industry, the environment and host communities” (UNEP and WTO 2005). They also established a framework for tourism according to the three pillars of sustainable development (Error! Reference source not found.).

Likewise, the European Union launched the European Tourism Indicators System (EC 2013) as the result of the Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism (EC 2007) and the EU Sustainable Development Strategy (EC 2010). It defined a comprehensive monitoring system to evaluate European destinations concerning sustainability and subdivided into four categories:

1) destination management; 2) social and cultural impact; 3) economic value; and 4) environmental impact.

More recently, to strengthen tourism’s contribution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the United Nations Statistics Division has launched an initiative “Towards a Statistical Framework for Measuring Tourism Sustainability” (MST) to create indicators adapted to the achievement of the SDGs in the field of tourism to support decision-making (UNWTO 2017a). Despite the growing use of the SDGs targets by policy-makers and tourism players, there are

still difficulties in measuring and monitoring progress, contribution and impacts on the SDGs and what this means in practice for host communities.

Source: UNEP and UNWTO, 2005: 20. Figure 1. Sustainable tourism framework

In short, going beyond the vast reflection on the concept of sustainable tourism, we will then look at how to operationalise an analysis framework, adjustable to the circumstances of the location, scale and nature of each tourist initiative.

This process will involve the creation of indicators capable of translating an integrated and shared vision of sustainability by the different partners. The objective is to provide reliable, up-to-date and understandable information on the positive and negative repercussions on local communities and destinations, so that initiatives can be designed, accompanied by preventive or corrective measures to make tourist destinations and activities more viable and attractive.

4. ANALYSING CREATIVE TOURISM AND ITS IMPACTS

The growing competitiveness and diversity of tourism products and destinations as a result of the globalisation dynamics and new forms of production and consumption led to the exploitation of more and more initiatives that seek to take advantage of culture-based creativity experiences of tourism. The objective is, usually, to offer to visitors or tourists unique and authentic opportunities to immerse themselves in cultural dynamics and places that foster co-creation and learning with members of the host community. Besides, these experiences benefit from the growth of the cultural and creative sector and synergies with tourism, contributing to the development of new products, experiences and markets. Based on creative capital and the use of existing local resources, they are trying to respond to the needs and aspirations of communities and ensure visitor satisfaction (about this theme see, for example, Richards and Raymond 2000; Prince 2011; UNESCO Creative Cities Network 2006; Korez-Vide 2013b).

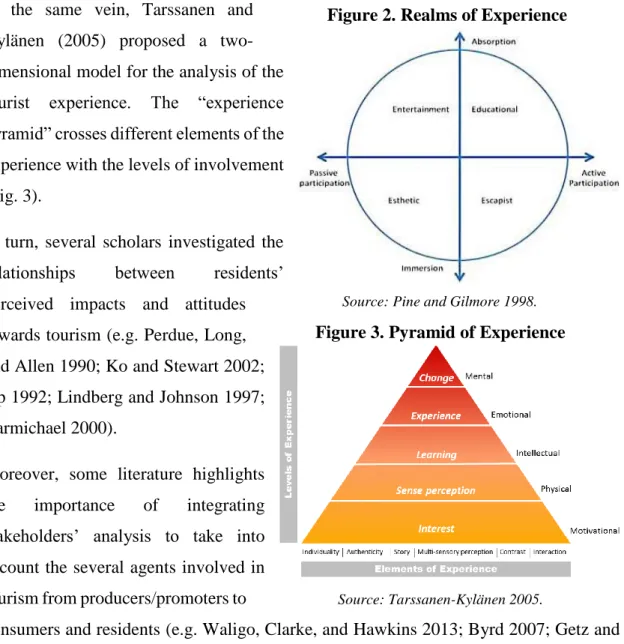

Several authors have tried to deepen the theoretical framework about tourist experiences, which are useful for the development of our model. Particularly interesting are the contributions of the “experience economy”, reflecting on the different experience realms (entertainment, education; aesthetics and escapism) and the level of participation (passive to active) and the emotional mode, that is, the way that memorable and unique experiences produce physical, personal, emotional, spiritual and intellectual sensations (Pine and Gilmore 1999) (Fig. 2).

In the same vein, Tarssanen and Kylänen (2005) proposed a two-dimensional model for the analysis of the tourist experience. The “experience pyramid” crosses different elements of the experience with the levels of involvement (Fig. 3).

In turn, several scholars investigated the relationships between residents’ perceived impacts and attitudes towards tourism (e.g. Perdue, Long, and Allen 1990; Ko and Stewart 2002; Ap 1992; Lindberg and Johnson 1997; Carmichael 2000).

Moreover, some literature highlights the importance of integrating stakeholders’ analysis to take into account the several agents involved in tourism from producers/promoters to

consumers and residents (e.g. Waligo, Clarke, and Hawkins 2013; Byrd 2007; Getz and Timur 2012).

These approaches are particularly useful for analysing the motivations, behaviours and perceptions of tourists, residents and promoters. In particular, in creative tourism, where the interactive process between the different actors is fundamental for the construction of the experience, it is necessary to consider these elements that influence the quality of the activities and the perceived impacts.

Although the concept of creative tourism has flourished as a more sustainable tourism model, preserving and valuing territories and communities without compromising their future, few studies in this field take into account sustainability criteria in their evaluation practices (Buaban 2016; Korez-Vide 2013a, 2013b; Qiu et al. 2019). One of the rare

Source: Pine and Gilmore 1998.

Source: Tarssanen-Kylänen 2005. Figure 2. Realms of Experience

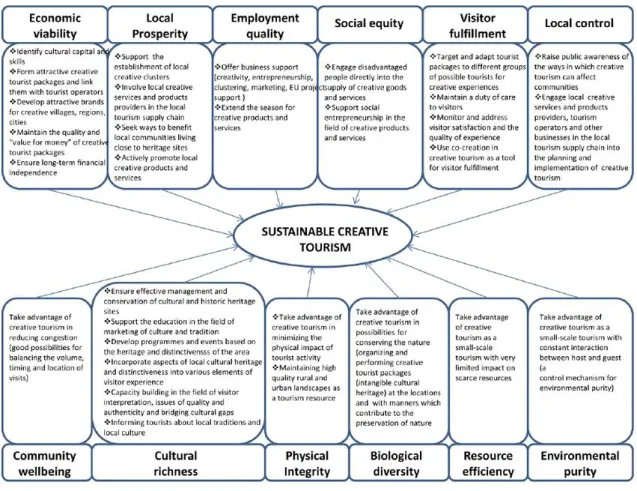

examples that tries to incorporate different dimensions of sustainability is the study developed by Korez-Vide (2013b) (see Fig. 4).

However, most of the published analyses that focus on the economic benefits of cultural and creative activities for tourism generally try to capture their direct and indirect impacts at the following four levels:

1. direct and quantifiable impacts (e.g. contributions to GDP, gross value added, employment and exports);

2. indirect and quantifiable impacts (e.g. multiplier effects on other sectors that are in inter-industrial relationships with creative industries and inter-consumption linkages);

3. direct and non-quantifiable impacts (e.g. creative inputs that contribute to increasing the level of industrial innovation and differentiation);

Source: Korez-Vide (2013b: 86)

4. indirect impacts and non-quantifiable impacts (e.g. contribution to improving quality of life, well-being, cultural diversity, citizenship and civic participation, identity, education).

In general, there are some conceptual and operational issues that are problematic, namely related to the nature of offered cultural and creative activities, their niche scale of operation, and the lack of systematic evidence of the multiple effects on territories and local communities.

More research is also needed to illuminate the relationships and networks that underpin creative processes to improve knowledge about these activities and their spill-over effects (Jeffcutt and Pratt 2002; Comunian 2010).

5. AN IMPACT ASSESSMENT MODEL FOR SUSTAINABLE CREATIVE TOURISM PROJECTS

As part of its participation in the CREATOUR project, this research team has developed an integrative impact assessment model that combines the multiple dimensions of sustainable development to measure the numerous impacts on the different territories. Taking into account the specificity of creative tourism activities, our model proposes an extension of conventional discourse on sustainability integrating culture as a dimension, but also as a resource and condition of development processes, and above all as a basis for, and result, sustainable development (as discussed by several authors, such as Hawkes 2001; Nurse 2006; Duxbury and Gillette 2007; Duxbury and Jeannotte 2012; Joost Dessein et al. 2015; UNESCO 2015; Soini and Dessein 2016; Meireis 2018).

Furthermore, the introduction of a cultural perspective into local and sustainable development planning recognises that the well-being of a community involves not only to improve social, economic and environmental conditions but also the vitality and quality of life of communities and places, through, for example, the cultural involvement, access, representation and expression of its members or the conservation and preservation of the diverse tangible and intangible forms of culture.

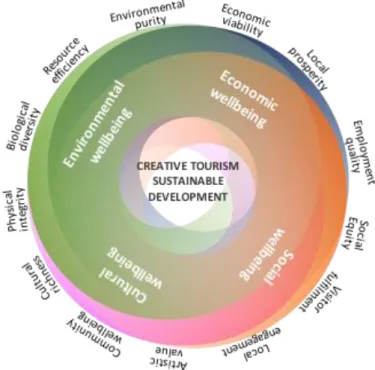

Thus, the proposed analytical model considers four intertwined dimensions of sustainable development: economic, social, environmental and cultural well-being.

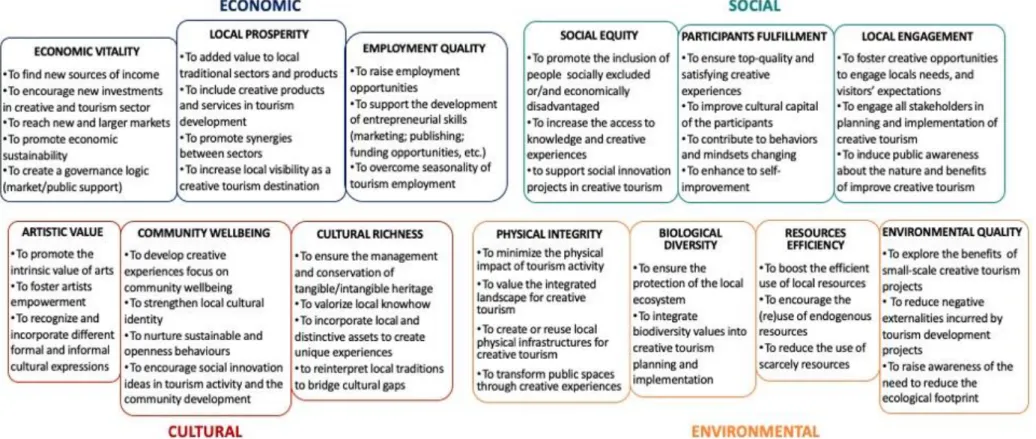

Subsequently, these are translated into thirteen sub-dimensions that allow the monitoring and assessment of the impacts of creative tourism practices (as illustrated in Fig. 5).

Accordingly, for each sub-dimension, a set of criteria that reflected sustainable objectives is presented, which contributes to designing the impact assessment framework of creative tourism (see Fig. 6).

Source: Authors’ elaboration, drawing upon the work of UNEP and UNWTO, 2005: 20) Figure 5. Creative Tourism Sustainable Development Model

Source: Authors ‘elaboration, inspired by Korez-Vide (2013: 86)

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt To understand how the territorial context influences the nature of the projects and the obtained effects, the following issues were considered in the application of this model:

• the resources involved (natural, cultural, physical and human) and the places where the experiences take place (from artisans’ ateliers to tourist itineraries).

• the set of actors involved or affected by these experiences (promoters, participants, inhabitants)

• the motivations/expectations that influence the nature and quality of the experience and, consequently, the type of satisfaction/dissatisfaction enjoyed.

• the contribution of cultural and creative activities to the development of these tourist experiences that encourage connections with culture and the local environment and more sustainable practices (Fig. 7).

Source: own elaboration.

The application and exploratory analysis of this model in the scope of the CREATOUR project have involved all the pilot initiatives in the discussion of these dimensions pointed to some challenges, opportunities and constraints in the diversity of situations found in creative tourism pilot initiatives. In the future, it will enable the creation of an operative toolkit to self-monitor the impacts produced on their territories and communities.

Fig. 8 Components of creative tourism experience

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt 6. CONCLUSIONS

This article aims to support the reflection on the role of creativity and culture in the development of tourist activities that can constitute sustainable experiences and alternatives to mass and overcrowded forms of tourism. To this end, it discusses the need to develop assessment tools in the field of creative tourism to identify potential, intentional or unintentional impacts that consider the economic, social, environmental and cultural dimensions of sustainable development.

Therefore, the proposed analysis model combines the various dimensions of sustainability for the well-being of communities, but at the same time underline the innovative and cultural nature of these interactive and reciprocal learning experiences as a form of tourism. In this sense, this integrative approach goes beyond traditional conceptions about tourism and its actors and sustainable development. This approach is also context-sensitive and aims to support the planning and evaluation of creative tourism. Thus, it considers the range of resources and places used but also the actors, their motivations/expectations and the satisfaction/dissatisfaction reactions to these experiences. Moreover, it appraises the contribution of cultural and creative activities to the development of these tourist experiences.

In conclusion, monitoring and evaluating the impacts on creative tourism is essential for participatory policymaking and the creation of satisfying experiences for tourists, residents and promoters, but also communities. It is a tool that is able to identify positive and negative repercussions to take preventive or corrective measures, build innovative solutions that improve the competitiveness of destinations, making them more viable and attractive.

However, the proposed model needs a broader and longer application to better understand the various impacts and to improve the methods to measure it on a given territory with their specificities, but also in the different sectors of activity and on the several participants.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt Acknowledgement

This work was developed within the CREATOUR project (no. 16437), which is funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT/MEC) through national funds and co-funded by FEDER through the Joint Activities Programme of COMPETE 2020 and the Regional Operational Programmes of Lisbon and Algarve.

REFERENCES

AP, John. 1992. “Residents’ Perceptions on Tourism Impacts.” Annals of Tourism Research 19 (4). Elsevier: 665–90.

ASMELASH, A.G., SATINDER, K. (2019) “Assessing Progress of Tourism Sustainability: Developing and Validating Sustainability Indicators”, Tourism Management 71 (April): 67-83. BALAS, M., STRASDAS, W. (2019) “Sustainability in Tourism: Developments, Approaches and Clarification of Terms - Paper". TEXTE 53/2019. On behalf of German Environment Agency.

Umweltbundesamt. Available at:

https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/sites/default/files/medien/1410/publikationen/texte_53-2019_paper-sustainable-tourism-en_190429.pdf.

BELLINI, N., GRILLO, F., LAZZERI, G., PASQUINELLI, C. (2017) “Tourism and Regional Economic Resilience from a Policy Perspective: Lessons from Smart Specialization Strategies in Europe”, European Planning Studies 25 (1): 140-53.

BLANCAS, F.J., González, M., LOZANO-OYOLA, M., PÉREZ, F. (2010) “The Assessment of Sustainable Tourism: Application to Spanish Coastal Destinations”, Ecological Indicators 10 (2): 484-92.

BOND, A.J., MORRISON-SAUNDERS, A. (2011) “Re-Evaluating Sustainability Assessment: Aligning the Vision and the Practice”, Environmental Impact Assessment Review 31 (1): 1-7.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt BUABAN, M. (2016) “Community-Based Creative Tourism Management to Enhance Local Sustainable Development in Kanchanaburi Province, Thailand.” Doctoral Thesis, University of Exeter. Available at https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/handle/10871/24246.

BYRD, E.T. (2007) “Stakeholders in Sustainable Tourism Development and Their Roles: Applying Stakeholder Theory to Sustainable Tourism Development”, Tourism Review. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

CARMICHAEL, B.A. (2000) “A Matrix Model for Resident Attitudes and Behaviours in a Rapidly Changing Tourist Area”, Tourism Management 21 (6): 601-11.

CEC (1999) ESDP - European Spatial Development Perspective: Towards Balanced and Sustainable Development of the Territory of the European Union. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publ. of the European Communities.

——— (2001a) “European Governance: A White Paper", COM(2001) 428 Brussels: Commission of the European Communities.

——— (2001b) Directive 2001/42/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Assessment of the Effects of Certain Plans and Programmes on the Environment. Official Journal, 197.

CERNAT, L., GOURDON, J. (2007) “Is the Concept of Sustainable Tourism Sustainable? Developing the Sustainable Tourism Benchmarking Tool”. Available at https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00557121

COHEN, E. (1987) “‘Alternative Tourism’ – A Critique”, Tourism Recreation Research 12 (2): 13-18.

COMUNIAN, R. (2010) “Networks of Knowledge and Support. Mapping Relations between Public, Private and Not for Profit Sector in the Creative Economy” 50th Congress of the ERSA: Sustainable Regional Growth and Development in the Creative Knowledge Economy, 19-23 August 2010, Jönköping, Sweden, European Regional Science Association.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt DEHOORNE, O., DEPAULT, K., MA, S-Q., CAO, H-H. (2014) “International tourism: Geopolitical dimensions of a global Phenomenon” in: Cao, B.Y., Ma, S-Q., Cao, H-H. (eds)

Ecosystem assessment and fuzzy systems management, vol 254. Springer, Cham.: 389-396.

DELISLE, M-A., JOLIN, L. (2007) Un Autre Tourisme Est-Il Possible? Éthique, Acteurs,

Concepts, Contraintes, Bonne Pratique, Ressources. Collection Tourisme. Québec: Presses de

l’Université du Québec.

DUXBURY, N., GILLETTE, E. (2007) “Culture as a Key Dimension of Sustainability: Exploring Concepts, Themes, and Models” Creative City Network of Canada. Centre of Expertise on Culture and Communities, Working Paper no.1. Available at

https://ci.nii.ac.jp/naid/10025271582/en/.

DUXBURY, N., JEANNOTTE, M.S. (2012) “Including Culture in Sustainability: An Assessment of Canada’s Integrated Community Sustainability Plans”, International Journal of Urban

Sustainable Development 4 (1): 1-19.

DUXBURY, N., RICHARDS, G. (2019) A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism. Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 1-14.

EADINGTON, W.R., SMITH, V.L. (1992) Tourism Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the

Development of Tourism, University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, PA.

E.C. (2002a) A Handbook for Impact Assessment in the Commission – How to do an Impact

Assessment. Brussels: European Commission.

——— (2002b) “Communication on Impact Assessment” COM(2002) 276 Final, from 5.6.2002. Brussels: European Commission.

——— (2005) Impact Assessment Guidelines. SEC(2005) 791, from 15.6.2005. with Annexes. Brussels: European Commission.

——— (2007) “Communication from the Commission – Agenda for a Sustainable and Competitive European Tourism” COM/2007/0621 Final. Brussels: European Commission.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt ——— (2009) Impact Assessment Guidelines. SEC(2009) 92. Brussels: European Commission. ——— (2010) “Europe, the World’s No 1 Tourist Destination – a New Political Framework for Tourism in Europe (COM(2010) 352 Final).” European Commission.

——— (2013) The European Tourism Indicator System: Toolkit for Sustainable Destinations. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

FAYOS‑SOLÀ, E. (2015) “Sustainability and Shifting Paradigms in Tourism”, PASOS. Revista

de Turismo y Patrimonio Cultural 13 (6): 1297-99.

FIGINI, P. (2019) “The Economic Impact of Tourism in the European Union.” Final Report Contract GRO-SME-17-C-091a/C of the European Commission, Executive Agency for Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises (EASME).

FISCHER, T.B. (2007) The Theory and Practice of Strategic Environmental Assessment:

Towards a More Systematic Approach, London; Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

FRECHTLING, D. (2013) “The Economic Impact of Tourism: Overview and Examples of Macroeconomic Analysis”, UNWTO Statistics and TSA Issues Paper Series.

GASPARATOS, A. (2010) “Embedded Value Systems in Sustainability Assessment Tools and Their Implications”, Journal of Environmental Management 91 (8): 1613-22.

GERTLER, P.J., MARTINEZ, S., PREMAND, P., RAWLINGS, VERMEERSCH, C.M.J. (2016) Impact evaluation in practice. The World Bank.

GETZ, D., TIMUR, S. (2012) “Stakeholder Involvement in Sustainable Tourism: Balancing the Voices”, in W.F. Theobald (ed.) Global Tourism. London: Routledge. 230-247

HALL, C.M. (2010) “Changing Paradigms and Global Change: From Sustainable to Steady-State Tourism”, Tourism Recreation Research 35 (2): 131-43.

HARDY, A., BEETON, R.J.S., PEARSON, L. (2002) “Sustainable Tourism: An Overview of the Concept and Its Position in Relation to Conceptualisations of Tourism”, Journal of Sustainable

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt HAWKES, J. (ed. 2001) The Fourth Pillar of Sustainability: Culture’s Essential Role in Public Planning. Victoria, Australia: Common Ground Publishing Pty Ltd in association with the Cultural Development Network.

HOLDEN, A. (2005) Tourism Studies and the Social Sciences, London; New York: Routledge.

HOLDEN, P. (ed. 1984) “Alternative Tourism: Report of the Workshop on Alternative Tourism with a Focus on Asia Chiang Mai”, Thailand: Ecumenical Coalition on Third World Tourism. HUNTER, C. (1997) “Sustainable Tourism as an Adaptive Paradigm”, Annals of Tourism

Research 24 (4): 850-67.

JEFFCUTT, P., PRATT, A.C. (2002) “Managing Creativity in the Cultural Industries”, Creativity

and Innovation Management 11 (4): 225-33.

DESSEIN, J., SOINI, K., FAIRCLOUGH, G., HORLINGS, L., (eds. 2015) “Culture in, for and as Sustainable Development. Conclusions from the COST Action IS1007 Investigating Cultural Sustainability”. Finland: University of Jyväskylä. Available at

http://www.culturalsustainability.eu/conclusions.pdf.

KO, D-W, STEWART, W.P. (2002) “A Structural Equation Model of Residents’ Attitudes for Tourism Development”, Tourism Management 23 (5). Elsevier: 521-30.

KO, T.G. (2005) “Development of a Tourism Sustainability Assessment Procedure: A Conceptual Approach”, Tourism Management 26 (3): 431-45.

KO, T.G. (2003) “Development of a Tourism Sustainability Assessment Methodology Based on Stakeholder Inputs: A Conceptual Approach”, International Journal of Tourism Sciences 3 (1): 17-46.

KOREZ-VIDE, R. (2013a) “Enforcing Sustainability Principles in Tourism via Creative Tourism Development”, Journal of Tourism Challenges and Trends 6 (1): 35-57.

——— (2013b) “Promoting Sustainability of Tourism by Creative Tourism Development: How Far Is Slovenia”, Innovative Issues and Approaches in Social Sciences 6 (1): 77-102.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt LERTCHAROENCHOKE, N. (1999) “Alternative Tourism”, Abac Journal 19 (2): 23-32.

Lindberg, Kreg, and Rebecca L. Johnson. 1997. “Modeling Resident Attitudes toward Tourism”,

Annals of Tourism Research 24 (2): 402-24.

McCOOL, S.F., MOISEY, R.N. (2008) “Frameworks and Approaches”, in S.F. McCool, R.N. Moisey, Tourism, Recreation, and Sustainability: Linking Culture and the Environment, 2nd

edition, 17-18. Wallingford (England); Cambridge (MA): CABI.

MEIREIS, T. (2018) “Sustainable Development and the Concept of Culture–an Ethical View”, in T. Meireis, G. Rippl (eds.) Cultural Sustainability: Perspectives from the Humanities and Social

Sciences, 47-59. London: Routledge.

Nurse, K. (2006) “Culture as the Fourth Pillar of Sustainable Development. Prepared for: Commonwealth Secretariat”, Small States: Economic Review and Basic Statistics 11: 28-40. Available at http://www.fao.org/sard/common/ecg/2700/en/Cultureas4thPillarSD.pdf.

OECD (1997) Regulatory Impact Analysis: Best Practices in OECD Countries. Paris: OECD Publishing.

——— (2000) “Towards Sustainable Development: Indicators to Measure Progress”, in

Proceedings of the OECD Rome Conference, Vol. 737. Paris.

——— (2004) Measuring Sustainable Development. Available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264020139-en.

——— (ed. 2006) “Applying Strategic Environmental Assessment: Good Practice Guidance for Development Co-Operation”. DAC Guidelines and Reference Series. Paris: OECD Publishing.

——— (2008) “Conducting Sustainability Assessments”. Available at https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264047266-en.

——— (2009) Regulatory Impact Analysis. OECD Reviews of Regulatory Reform. OECD Publishing.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt ——— (2010) Guidance on Sustainability Impact Assessment. OECD Publishing. Available at

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264086913-en.

——— (2016) Better Policies for Sustainable Development 2016. OECD Publishing.

PABLO-ROMERO, M.P., MOLINA, J.A. (2013) “Tourism and Economic Growth: A Review of Empirical Literature”, Tourism Management Perspectives 8: 28-41.

PEARCE, D.G. (1992) “Alternative Tourism: Concepts, Classifications, and Questions”, Tourism

Alternatives: Potentials and Problems in the Development of Tourism, 15-30.

PERDUE, R.R., PATRICK T.L., ALLEN, L. (1990) “Resident Support for Tourism Development”, Annals of Tourism Research 17 (4). Elsevier: 586-99.

PINE, B.J., GILMORE, J.H. (1999) The Experience Economy: Work Is Theatre & Every Business

a Stage, Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

PRINCE, S. (2011) “Establishing the Connections Between the Goals of Sustainable Development and Creative Tourism”, Student thesis. DiVA. Available at

http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-161160.

QIU, H., Fan, D.X.F., LYU, J., LIN, P.M.C., JENKINS, C.L. (2019) “Analyzing the Economic Sustainability of Tourism Development: Evidence from Hong Kong”, Journal of Hospitality &

Tourism Research 43 (2): 226-48.

RICHARDS, G., RAYMOND, C. (2000) “Creative Tourism”, ATLAS News 23: 16-20.

RICHARDS, G., DUIF, L. (2018) Small Cities with Big Dreams: Creative Placemaking and

Branding Strategies, New York: Routledge.

RICHARDS, G., WILSON, J. (eds.) (2007) “Tourism, Creativity and Development. Contemporary Geographies of Leisure”, Tourism and Mobility 10. London; New York: Routledge.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt ROMÃO, J., NIJKAMP, P. (2017) “Impacts of Innovation, Productivity and Specialization on Tourism Competitiveness – a Spatial Econometric Analysis on European Regions”, Current

Issues in Tourism, (August): 1-20.

SALA, S., CIUFFO, B., NIJKAMP, P. (2015) “A Systemic Framework for Sustainability Assessment”, Ecological Economics 119 (November): 314-25.

SCHWAB, K., SALA i MARTIN, X., World Economic Forum (2016) The Global Competitiveness Report 2016-2017. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

SHARPLEY, R. (2000) “Tourism and Sustainable Development: Exploring the Theoretical Divide”, Journal of Sustainable Tourism 8 (1): 1-19.

——— (2002) “Sustainability: A Barrier to Tourism Development?”, Tourism and Development:

Concepts and Issues, 319-37.

SHARPLEY, R., TELFER, D.J. (2008) Tourism and Development in the Developing World, London; New York, NY: Routledge.

SHAW, D., SYKES, O. (2004) “The Concept of Polycentricity in European Spatial Planning: Reflections on its Interpretation and Application in the Practice of Spatial Planning”,

International Planning Studies 9 (4): 283-306.

SINGH, R.H., MURTY, R., GUPTA, A.B., DIKSHIT, A. (2009) “An Overview of Sustainability Assessment Methodologies”, Ecological Indicators 9 (2): 189-212.

SOINI, K., DESSEIN, J. (2016) “Culture-Sustainability Relation: Towards a Conceptual Framework”, Sustainability 8 (2): 167.

STYNES, D.J. (1997) “Economic Impacts of Tourism”. Illinois Bureau of Tourism, Department of Commerce and Community Affairs.

TARSSANEN, S., KYLÄNEN, M. (2005) “A Theoretical Model for Producing Experiences – a Touristic Perspective”, Articles on Experiences 2 (1): 130-49.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt TORRES-DELGADO, A., PALOMEQUE, F.L. (2014) “Measuring Sustainable Tourism at the Municipal Level”, Annals of Tourism Research 49 (November): 122-37.

TORRES-DELGADO, A., SAARINEN, J. (2014) “Using Indicators to Assess Sustainable Tourism Development: A Review”, Tourism Geographies 16 (1): 31-47.

TYRRELL, T.J., JOHNSTON, R.J. (2006) “The Economic Impacts of Tourism: A Special Issue”,

Journal of Travel Research 45 (1): 3-7.

UN (ed. 2007) Indicators of Sustainable Development: Guidelines and Methodologies. 3rd edition,

New York: United Nations.

UNEP, and WTO (2005) Making Tourism More Sustainable – A Guide for Policy Makers. Paris: UNEP, Division of Technology, Industry and Economics.

UNESCO (2015) “UNESCO’s Work on Culture and Sustainable Development: Evaluation of a Policy Theme.” Final Report. Nov 2015. UNESCO. Available at

https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000234443.

UNESCO Creative Cities Network (2006) “Towards Sustainable Strategies for Creative Tourism”. Discussion Report of the Planning Meeting for 2008 International Conference on Creative Tourism. Santa Fe, New Mexico. USA.

WTO (1995) “Charter for Sustainable Tourism”, UNWTO Declarations 5 (4). UNWTO, Madrid.

——— (2017a) Tourism and the Sustainable Development Goals – Journey to 2030. World Tourism Organization.

——— (2017b) UNWTO Tourism Highlights: 2017 Edition. World Tourism Organization. VELLAS, F. (2011) “The Indirect Impact of Tourism: An Economic Analysis”, in Third Meeting of T20 Tourism Ministers. Paris, France.

WAAS, T., HUGÉ, J., BLOCK, T., WRIGHT, T., BENITEZ-CAPISTROS, F., VERBRUGGEN, A. (2014) “Sustainability Assessment and Indicators: Tools in a Decision-Making Strategy for Sustainable Development”, Sustainability 6 (9): 5512-34.

DINÂMIA’CET – Iscte, Centro de Estudos sobre a Mudança Socioeconómica e o Território Iscte- do Instituto Universitário de Lisboa

Sala 2W4 - D | ISCTE-IUL – Av. das Forças Armadas 1649-026 Lisboa, PORTUGAL

Tel. (+351) 210 464 031 / 210 464 197 | E-mail: dinamia@iscte-iul.pt | www.dinamiacet.iscte-iul.pt WALIGO, V.M., CLARKE, J., HAWKINS, R. (2013) “Implementing Sustainable Tourism: A Multi-Stakeholder Involvement Management Framework”, Tourism Management 36 (June): 342-53.

WCED (1987) Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development “Our Common Future.” Geneva: United Nations.

WEIDENFELD, A. (2018) “Tourism Diversification and Its Implications for Smart Specialisation”, Sustainability 10 (2): 319.

WISANSING, J.J., VONGVISITSIN, T.B. (2019) “Local Impacts of Creative Tourism Initiatives”, in N. Duxbury, G. Richards (eds.) A Research Agenda for Creative Tourism, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. 122-136.

WTO (ed. 2004) Indicators of Sustainable Development for Tourism Destinations: A Guidebook. Madrid: World Tourism Organization.

WTTC, WTO, and Earth Council (1995) Agenda 21 for the Travel & Tourism Industry: Towards Environmentally Sustainable Development. London; Madrid; San José, Costa Rica: World Travel & Tourism Council; World Tourism Organization; Earth Council.