(6) Kilpatrick, Z. M., P. A. Greenber, and J. P. Sanford. Splinter hemorrhages-their clinical significance. Arch Intern Med 115:730-735, 1965.

(7) Price, W. H. Gallbladder dyspepsia. Br MedJ 2:138-141, 1963.

(8) Dawber, T. R., W. B. Kann and L. P. Lyell. An approach to longitudinal studies in a community: the Fra-mingham Study. Ann NY Acad Sci 107:539-556, 1963.

(9) Fox, J. P., C. E. Hall, and M. R. Councy. The Seattle Virus Watch. II. Objectives, study population and its observa-tion, data processing and summary of illnesses. Am J Epide-miol 96:270-285, 1972.

(10) Feinstein, A. R. Clinical Biostatistics. St. Louis, C.V. Mosby, 1977.

(11) Langmuir, A. D. Epidemiology of airborne infection. Bacteriol Rev 25:173-181, 1961.

(12) Morrison, A. S., H. K. Jick, and H. W. Ory. Oral contraceptives and hepatitis. A report from the Boston

Colla-borative Drug Surveillance Program, Boston University Med-ical Center. Lancet 1:1142-1143, 1977.

e

Editorial Comment

Dr. Barrett-Connor's article has been summarized for the Epidemiological Bulletin because it makes a sub-stantial contribution to the application of epidemiol-ogy in the field of disease prevention and control. It addresses a subject of current controversy and dis-cussion in many Latin American and Caribbean coun-tries, and is important for the organization of services, teaching of epidemiology, and research in the countries of the Region.

National Registry

of Tumor Pathology in Brazil

During the VI International Cancer Congress, held in Sao Paulo, in 1954, a discussion was held on the need for an international coding system for neoplasms. As a result, the Nomenclature and Statistics Committee of the International Union against Cancer accepted the Manual of Tumor Nomenclature and Coding (MOTNAC), published by the American Cancer Society in 1951, as the basis for an international coding system. MOTNAC was revised in 1968. In 1976 it was succeeded by the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O), published by the World Health Organization.

Recognizing the importance of a uniform coding system for neoplasms, the Pan American Health Organization published a Portuguese language version of MOTNAC in 1972 and a Spanish version in 1974. These translations were widely distributed in Latin America. Spanish and Portuguese language versions of ICD-O were published by PAHO in 1977 and 1978, respectively.

Because of a lack of national statistics on cancer, the existence of only a small number of tumor registries (hospital and population-based), and the need for data on the incidence of cancer in Brazil, the National Div-ision of Chronic Degenerative Diseases in 1975 deve-loped a program for oncological coding.

In 1975 and 1976, 50 courses were held in 49 cities,

describing the methodology and value of the National Registry of Pathology. These courses were attended by 2,912 participants: 283 pathologists, 516 physicians from other specialities, 1,200 medical students, and 913 paramedics. Subsequently, didactic kits for coding diagnostic information were provided to the 109 labora-tories which participated in the initial phases of the program. The results of this initial phase, with all the histopathological data collected in 1975, were pub-lished in the "Registro Nacional de Tumores" (Brazi-lian Ministry of Health, 1978).

The success of this endeavor by the National Division of Chronic Degenerative Diseases and the interest of pathologists in the program stimulated continued work. As a result, the registry expanded into a national program designed to obtain information on the inci-dence of cancer throughout the entire country; this program is known as the National Registry of Tumor Pathology (NRTP).

In 1978 an Agreement was signed by the Ministry of Health and PAHO's Latin American Center for Health Sciences Information (BIREME) in Sao Paulo, for the development of a computerized registry which facili-tates storage and rapid analysis of large amounts of data.

As the coordinating and executive center, in 1978 BIREME contacted a large number of laboratories, in

12

.

ment was as simple or obvious as the situation which appeared to exist in infeaious disease, progressively sophisticated mathematics were developed by epidemi-ologists and biostatisticians, at a time when most research in the field of infectious disease involved clini-cal observations or experiments conducted in the labor-atory. The danger is that goodness of fit sometimes substitutes for common sense or biologic plausibility

(10). Chronic disease epidemiologists are often in the awkward position of analysis without hypothesis; in the absence of either an agent or a unique outcome, they must perform hypothesis-seeking exercises. As good statisticians and epidemiologists know, the pitfalls of data dredging greatly exceed those of hypothesis test-ing. The multiple possible analyses render almost a certainty that some variables will be significantly asso-ciated with some diseases.

In the days before linear regression and multiple logistic function, many infectious disease epidemiolo-gists personally gathered and manually tabulated their data. This experience clarified the sometimes remarka-ble limitations of data-which by virtue of categoriza-tion and computerizacategoriza-tion may gain unwarranted credi-bility. Experience gained in the shorter time-frame of some infectious processes also provide valuable insights about the hazards of early assumption. Farr (11) demon-strated a remarkable correlation of cholera mortalitv and altitude in 19th century London but failed to con-sider water as the variable of interest. A recent report

(12) of an excess of hepatitis among young women using oral contraceptives would have profited by a con-sideration of the probable differences in lifestyle among women who chose oral contraceptives as compared to those without such contraceptive practices.

Many infectious disease epidemiologists come from the ranks of clinicians and laboratorians, and lack the skills traditionally considered in the purview of the chronic disease epidemiologists. These skills are now essential to the discovery of those variables which, in the presence of the necessary agent, determine infection, disease, and outcome. Whereas the infectious agent can usually be isolated and enumerated with precision, the extraneous factors which determine morbidity and mortality are more difficult to quantify. It is the task of epidemiology to find other methods to assess with pre-cision the contribution of these factors to infectious disease. The arbitrary separation of infectious disease from chronic disease epidemiology in teaching and research does disservice to this need.

Conclusion

Some scientific disciplines are best able to answer certain questions in medicine. Much of modern epide-miological effort has been directed toward investigat-ing problems regardinvestigat-ing which the rest of science has

few useful leads. Any disease, acute or chronic, which lacks either a logical structure or a plausible hypothesis is difficult to study. But the identification of a necessary agent, microbial or otherwise, does not answer all rele-vant and important questions any more than demon-stration of an associated variable confirms causality or predicts prevention.

Epidemiologically, acute diseases differ from chronic diseases in two major aspects: immediacy of response and uniqueness of observation. The lessons learned in infectious disease, where the agent and outcome were more readily available to test predictions, must be shared with those epidemiologists who-in their haste to assign causality-sometimes abandon biologic wis-dom in favor of quantitative ideology. Many- of the unanswered questions in acute/infectious disease epidemiology need to be addressed by those techniques currently attributed to and taught with chronic disease epidemiology. Acute and chronic disease epidemiolo-gists have important lessons to offer each other. A shar-ing of experience and methodologies could avert the unfortunate plethora of truly terrible data analyzed ad nauseam, or good data poorly interpreted. Once these lessons have been learned, we should discard the quali-fiers and call an epidemiologist an epidemiologist. Acute and chronic disease epidemiologists are not separate and unrelated species, any more than acute and chronic diseases can be neatly categorized.

(Source: Reprinted from Elizabeth Barrett-Connor, "Infectious and Chronic Disease Epidemiology:

Separate and Unequal?". Am J Epideniol

109(3):245-249, 1979.)

References

(1) Commission on Chronic Illness. Chronic illness in a

large city-The Baltimore study. In Chronic lllness in the United States. Vol. IV. Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1957.

(2) Schocket, A. L. and H. L. Weiner. Lymphocytotoxic antibodies in family members of patients with multiple scle-rosis. Lancet 1:571-573, 1978.

(3) Stewart, G. T. Limitations of the germ theory. Lancet

1:1977-2081, 1968.

(4) Emery, A. E. H., R. Anand, N. Danford, et al. Arylhy-drocarbonhydroxylase inducibility in patients with cancer.

Lancet 1:470-471, 1978.

(5) Weller, T. H. and C. W. Sorensen. Enterobiasis: its incidence and symptomatology in a group of 505 children. N Engl ] Med 224:143-146, 1941.

order to update information from those involved in the initial phase of the program, and to recruit new members.

Between February and December 1979, each partici-pating laboratory received training in the use of ICD-O, available in Portuguese as of 1978.

The number of laboratories enrolled in the program in 1975-1976 was 109. That number has increased to 306 in 1981 and covers 106 cities in 26 states. The laborato-ries are distributed as follows: 50 in medical schools ( 16.3 per cent) 14 in schools of dentistry (4.6 per cent), 22 in cancer hospitals (7.2 per cent), 10 in other specialized hospitals (3.3 per cent), 66 in general hospitals (21.6 per cent), and 144 private laboratories (47.0 per cent).

It has been estimated that the program involves 90 per cent of all laboratories and that it has collected informa-tion from more than 95 per cent of all cancer cases histologically diagnosed in Brazil.

Data collected by the program include the primary histological diagnoses from all anatomical sites as well as dysplastic lesions of the uterine cervix. These data originate from two sources: surgical pathology exami-nations and autopsies.

Cervical dysplasia data were collected because of the increasing number of cervical cancer detection pro-grams started throughout the country. Data were col-lected from 279 laboratories (91.2 per cent of all those who participated) and represent 401,851 diagnoses (369,767 primary cancer diagnoses of all anatomical sites and 32,084 of uterine cervical dysplasia). Of all diagnoses, 99.5 per cent were obtained from surgical pathology examinations and 0.5 per cent from auto-psies. Because of the large percentage of surgical pathology diagnoses, any overlap between surgical and autopsy diagnoses would not be significant.

The small number of diagnoses recorded for the leukemias were obtained chiefly from autopsies. The cytohematological diagnoses of the peripheral blood and myelograms are not included, since they were not under study in this phase of the program.

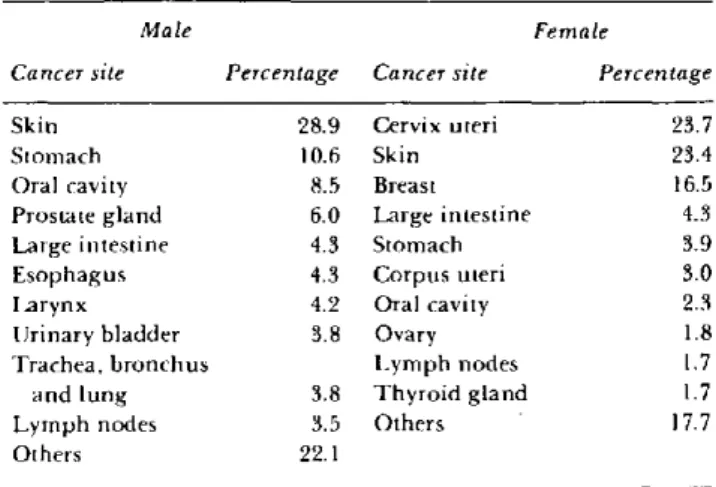

The data covering the period 1976-1980 have recen tly been published (in Portuguese and English in Cancer in Brazil: Histopathological Data) by the Ministry of Health of Brazil. The main purpose of the publication is to present information on the nature and extent of cancer in Brazil. It gives detailed information on labor-atory findings on the various cancer types by geogra-phical area, sex, and age. Table I presents a general view of the percent distribution by sex of the 10 leading primary cancer sites.

The NRTP program has as its immediate objectives to increase diagnostic precision and plan for future requirements for services and training in pathology. These data should provide excellent information lead-ing to the identification of research areas and add to the knowledge on cancer incidence in Brazil by relating

Table 1. Percent distribution of the 10 leading primary cancer sites, according to the National Registry of Tumor

Pathology, Brazil, 1976-1980.

Male Female

Cancer site Percenlage Cancer site Percentage

Skin 28.9 Cervix uteri 23.7 Stomach 10.6 Skin 23.4 Oral cavity 8.5 Breast 16.5

Prostate gland 6.0 Large intestine 4.3 Large intestine 4.3 Stomach 3.9 Esophagus 4.3 Corpus uteri 3.0 Larynx 4.2 Oral cavity 2.3 Urinary bladder 3.8 Ovary 1.8 Trachea, bronchus Lymph nodes 1.7 and lung 3.8 Thyroid gland 1.7 Lymph nodes 3.5 Others 17.7

Others 22.1

these histologically diagnosed cases to the population at risk.

Requests or correspondence should be addressed to:

Programa RNPT, Instituto Nacional de Cancer, Caixa Postal 22018, CEP 20237 - Rio de Janeiro, R.J., Braízil.

(Source: Cancer in Brazil: Histopathological Data 1976-80. Rio de Janeiro, National Cancer Control

Campaign, Ministry of Health, Brazil, 1982.)

Editorial Comment

The amount of data collected from diagnostic infor-mation sheds light on the magnitude of the cancer problem among the Brazilian population. The distri-bution of relative frequencies proceeding from the var-ious pathology centers has epidemiological value because it probably represents a great proportion of

diagnostically confirmed cases. Even though indicators

of risk in the population to the various types of cancer should be expressed in incidence rates, these data expressed in percentages are useful in order to approx-imate knowledge of frequencies and, mostly, to direct epidemiological research. The data presented in rela-tive frequencies for each state in Brazil by age group and sex reveals interesting geographic patterns of pathol-ogy which could spark research interest.

Regarding organization of cancer registries, the pub-lication referred to above is an indication of the efforts

needed to collect case data, that is, data that would become the numerator in an incidence rate. These efforts would justify the total collection of data which would include sources other than pathology laborato-ries, such as x-rays for the diagnosis of lung cancer. If the infrastructure of statistical data is well developed, then knowledge of other aspects such as population at risk, can be obtained.

This study in Brazil stimulates and motivates the intention to repeat the experience aimed at developing population-based registries in large cities which will point to research areas, indicate trends, aid in the follow-up of patients, and finally, be useful for evaluat-ing control programs, one of the central objectives in public health.

Reports on Meetings and Seminars

Fourth Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Diarrheal Diseases Control Programs'

At its fourth meeting, held in Geneva on 14-18 March 1983, the Technical Advisory Group (TAG) of the Diar-rheal Diseases Control (CDD) Program reviewed in depth the activities of the Program during 1981 and 19822. It noted with satisfaction the progress made to date and made recommendations3 with regard to future activities. Some of these recommendations are high-lighted below:

Health Services Component

* The Program should continue to support the preparation of plans of operation for national CDD programs, ensuring full integration with planning for primary health care (PHC).

* Increased emphasis should be placed on national training of health workers, including the development of additional national training centers, and efforts should be made to promote the inclusion of diarrheal disease control in the curricula of training institutions for health workers.

* Governments should maximize their commitment to hasten the implementation and expansion of nation-al CDD programs.

' Wkly Epidem Rec 58(24):181-188, 1983.

2 Third Program Report, 1981-1982. Unpublished document WHO/CDD/83.8. See Wkly Epidem Rec 58(21):157, 1983.

' The full report of the TAG (unpublished document WHO/CDD/83.7) is available in English and French and may be obtained from: The Program Manager, CDD Program, WHO, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland.

* The highest priority should continue to be given to the reduction of diarrheal mortality through oral rehy-dration therapy (ORT), while other control strategies to reduce diarrhea morbidity should also be promoted in cooperation with governments and other agencies and WHO programs.

* Every effort should be made to obtain better quality data on morbidity and mortality due to diarrheal dis-eases; arrangements for surveillance and reporting of control activities should be built into national pro-grams from their onset.

Research Component

* In the area of biomedical research, the Steering Committees should continue to play an active role in the management of the activities of the global Scientific Working Groups (SWGs); a particular effort should be made to stimulate activities in regions where such research is now receiving limited support.

* Operational research needs should be identified through meetings between national CDD program staff, national researchers, and WHO Program staff; greater attention should be given to research when for-mulating and evaluating national CDD programs. The Program should explore ways of strengthening nation-al operationnation-al research capacity, particularly in coun-tries with active CDD programs.

* The systematic reviews being carried out by the Program to define the most important of the potential interventions (in addition to ORT) for diarrhea control should be completed in 1983 and a full report presented at the next TAG meeting on their implications for research, for operations, and for linkages with other programs.

14