Hemoglobin levels and

prevalence of anemia in

pregnant women assisted in

primary health care services,

before and after fortiication of

lour*

Níveis de hemoglobina e prevalência

de anemia em gestantes atendidas

em unidades básicas de saúde, antes

e após a fortiicação das farinhas

com ferro

Claudia Regina Marchiori Antunes Araújo

ITaqueco Teruya Uchimura

IIElizabeth Fujimori

IIIFernanda Shizue Nishida

IGiovanna Batista Leite Veloso

IVSophia Cornblutz Szarfarc

VI Paranaense Adventist Faculty, Ivatuba, PR.

II Department of Nursing at the State University of Maringá. Maringá, PR.

III Department of Collective Health at the School of Nursing of the University of

São Paulo, São Paulo, SP.

IV Positivo University. Curitiba, PR.

V Department of Nutrition at the University of São Paulo. São Paulo, SP.

* Funded by the CNPq (Process number 402295/2005-6).

Correspondência: Claudia Regina Marchiori Antunes Araújo. Adventist Faculty of Pa-raná. Rua Honorata Tereza da Rocha, 397, Vila Brasil, 86990-000 Marialva, PR. E-mail: clauaraujo@usp.br

Abstract

We evaluated hemoglobin-Hb levels and prevalence of anemia in pregnant women before and after fortification of flour. It was developed a study to evaluate inter-vention, of the type before and after, with independent population samples. Study was conducted in primary health care services in Maringá, PR. We assessed 366 and 419 medical records, Before and After implementation of fortiication. Pregnant women with Hb < 11g/dL were considered anemic. Data were submitted to multiple linear regression analysis. There was low prevalence of anemia affecting 12.3% and 9.4% pregnant women Before and After for-tiication (p > 0.05), but the Group After the fortiication had higher Hb levels (p < 0.05). Hb levels associated with Group, gestational age, previous pregnancy number, employ-ment and marital status (p < 0.05). Although the fortiication of lour may have had role in increasing the mean hemoglobin, we need consider the contribution of other variables not investigated.

Resumo

Avaliaram-se níveis de hemoglobina-Hb e prevalência de anemia em gestantes, antes e após a fortiicação das farinhas. Estudo de avaliação do tipo antes e depois, com amostras populacionais independentes, realizado em unidades básicas de saúde de Maringá, PR. Foram avaliados 366 pron-tuários de gestantes Antes da fortiicação obrigatória das farinhas, e 419 Após a forti-icação. Gestantes com Hb < 11g/dL foram consideradas anêmicas. Realizou-se análise de regressão linear múltipla. Veriicou-se baixa prevalência de anemia que afetava 12,3% e 9,4% das gestantes, Antes e Após a fortiicação (p > 0,05), porém o Grupo Após a fortiicação obrigatória apresentou média de Hb mais elevada (p < 0,05). Evidenciou-se associação entre Hb e Grupo, idade gestacional, gestação anterior, ocupação e situação conjugal (p < 0,05). Embora a fortiicação de farinhas possa ter um papel no aumento da média de hemoglobina, é preciso considerar a contribuição de outras variáveis não investigadas.

Palavras-chave: Anemia. Hemoglobinas. Deiciência de ferro. Gestantes. Alimentos fortiicados. Cuidado Pré-Natal.

Introduction

Iron-deficiency anemia is still a glo-bal problem and the most frequent and alarming nutritional deficiency in terms of collective health. Unlike the decreasing trend of other nutritional deicits, anemia continues to be present in all continents and social groups, although its occurrence remains associated with negative socio--environmental conditions1-2.

Pregnant women represent one of the most vulnerable groups, due to the high iron requirement to meet both the mother’s and the fetus’ needs3. It is estimated that 52% of pregnant women in developing countries have anemia, whereas this proportion is 23% in developed countries1. Although national data are not available, a review of studies that have been published in the last 40 years showed that the prevalence of ane-mia during pregnancy is high, despite the policies implemented to ight this disease4. Recent data from the Pesquisa Nacional de Demografia e Saúde da Criança e da Mulher (PNDS – National Demographic and Health Survey of Children and Women)5 showed a reduction in the prevalence of anemia in children aged between six and 59 months, although the same was not observed among non-pregnant women of childbearing age, who had a high rate of anemia, with a preva-lence of 29.4% in Brazil and relevant regio-nal differences. This is an alarming fact, as nearly one third of women of childbearing age already have anemia before becoming pregnant, in addition to the gestational period being the most critical in terms of body iron requirement.

de Suplementação de Ferro (National Iron Supplementation Program) in 200510.

Among the set of strategies aimed at iron-deiciency anemia control and reduc-tion implemented in Brazil, the regulareduc-tion of wheat and corn lour fortiication with iron and folic acid of December 2002 should be emphasized11. However, this resolution esta-blished an 18-month period for companies to meet the regulation, so that fortiication only became mandatory in June 2004.

Although the results of fortiication are expected in the long term, positive effects can be observed more quickly as physiologi-cal needs increase1. Thus, the present study aimed to assess hemoglobin levels and the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women, before and after lour fortiication with iron, with the purpose of understanding more about the impact of this intervention and enabling a point of reference for the evolu-tion of this problem in the city of Maringá, PR, Southern Brazil. Researchers expect that the results of this study will help to improve local anemia prevention and control progra-ms for pregnant women, including nursing interventions during prenatal care12.

Methods

The present subproject, approved by the State University of Maringá Research Ethics Committee (Oficial Opinion number 095/2006), was part of a broader research project*. This study was designed to assess a before-and-after intervention in inde-pendent population samples and it was developed in 22 of the 23 primary health units of the city of Maringá, state of Paraná. Data were obtained from the medical records of pregnant women cared for during prenatal follow-up in two periods: Before mandatory flour fortification, including pregnant women who had given birth be-tween June 2003 and May 2004 and others who had given birth at least one year after the effective implementation of the strate-gy, including pregnant women whose last menstruation occurred between June 2005 and May 2006. In 2004, before fortiication,

the public prenatal care service in Maringá covered approximately 45% of births; in 2006, after mandatory flour fortification with iron, nearly 56% of pregnant women received prenatal care in the city’s public service (Data from the SISPRENATAL and SINASC).

The minimum sample size of each group was calculated according to the following formula: n=Z2PQ./d2, where n=minimum sample size; Z=confidence coefficient, whose value adopted was 1.96 for an alpha of 0.05; P=prevalence; Q=prevalence com-plement (Q=1-P); and d=maximum error in absolute value. Considering the fact that there are no national studies in Brazil that have estimated the dimension of the pro-blem in pregnant women, a value of P=0.50 was adopted, which corresponds to a greater relationship between P and Q and expected accuracy d=5%. Thus, the following was obtained: n=1.962x0.50x0.50/0.052 = 384.

records were replaced for this group. The medical records of pregnant women who had problems associated with blood loss or hemoglobinopathies that justiied the continuing reduction in Hb were ex-cluded. The inal sample was comprised of 785 pregnant women: 366 in the Before mandatory lour fortiication group and 419 in the After fortiication group.

Data collection occurred between 2006 and 2007 and only included low-risk preg-nant women, whose medical records had at least the following information: date of the irst consultation, date of the last menstrua-tion, date of the blood test and Hb test result. In addition, socioeconomic-demographic data (age, level of education, employment and marital status) and gynecological--obstetric and prenatal history (gestational age, weight and height in the irst prenatal consultation, number of previous pregnan-cies and number of prenatal consultations). Maternal age was categorized as less than 20 years and equal to or more than 20 years; level of education as less than 8 years of education and equal to or more than 8 years of education; employment as having a paid job and unpaid job; marital status as with and without a partner; gestational age in the beginning of prenatal care as irst trimester (1 to 13 weeks), second tri-mester (14 to 27 weeks) and third tritri-mester (28 weeks and more)13; number of prenatal consultations as less than 7 consultations and equal to or more than 7 consultations; and number of previous pregnancies as none and one or more previous pregnan-cies. Nutritional status was categorized according to the Brazilian Ministry of Health recommendations14: low weight; adequate weight; and overweight/obesity.

Data on Hb referred to the first test requested in the irst prenatal consultation and, consequently, researchers considered that pregnant women were not receiving iron supplementation. Pregnant women with iron supplementation at the time of blood collection were not included in the sample. This was possible because the city has a relective tool attached to the medical

records, which is completed with data from the prenatal card, thus enabling informa-tion about the beginning of prenatal care and laboratory test results to be obtained, even when performed in other services. All tests were performed in the city’s Central Laboratory, which uses a Cell-Dyn 3000 (Abbott) automated cell counter to analyze Hb. Gestational age at the time of Hb as-sessment was calculated, considering the date of the last menstruation and the date of blood test. Pregnant women with an Hb count lower than 11.0g/dL1 were considered to be anemic. Data on Hb were analyzed according to the gestational trimester when the test was performed13.

Data analysis was performed with Epi-Info 6.0, Statistica 7.1 and Statistical Package for Social Sciences – SPSS, version 11.0. Chi-square test, Student’s t-test and variance analysis were used to analyze the data. Aiming to investigate the possible inluence of the variables studied on Hb levels, these data were submitted to multi-ple linear regression analysis. Hb level was considered as the dependent variable and the Non-fortiied and Fortiied groups and prenatal, obstetric, socioeconomic and de-mographic characteristics were considered as predictive variables. Variables that sho-wed an association in the bivariate analysis, with a signiicance level of 20% (p<0.20), were included in the model to prevent the exclusion of potentially important variables. A signiicance level of 5% (p<0.05) was used to identify associations.

Results

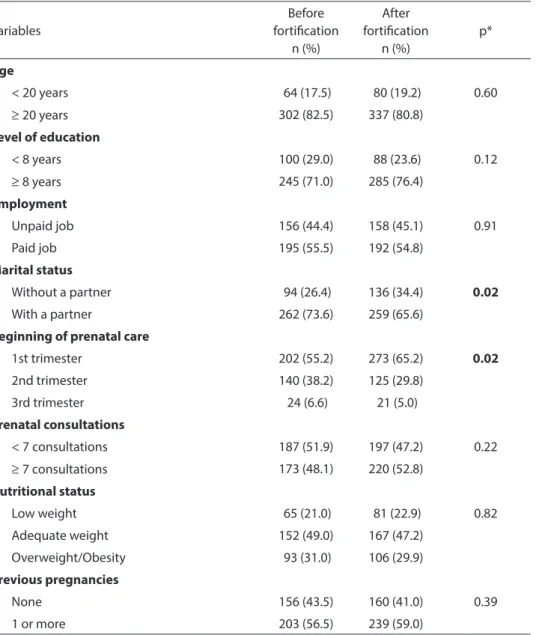

Table 1 shows the characteristics of pregnant women according to Groups, which differed in terms of marital status and beginning of prenatal care. A signiicantly higher proportion of pregnant women in the After mandatory lour fortiication group did not have a partner (8% and higher) and began prenatal care in the irst trimester (10% and higher).

weeks in the beginning of prenatal care, while that of the After fortiication group was 12.8±6.5 weeks (p<0.0001). Groups were homogeneous in terms of the other variables analyzed: a similar proportion of adolescents (<20 years); more than two thir-ds had completed primary school and more than half had a paid job; almost one third of both groups were overweight/obese and one ifth had low weight; the great majority

had already had at least one previous preg-nancy; and approximately half had had at least seven prenatal consultations (Table 1).

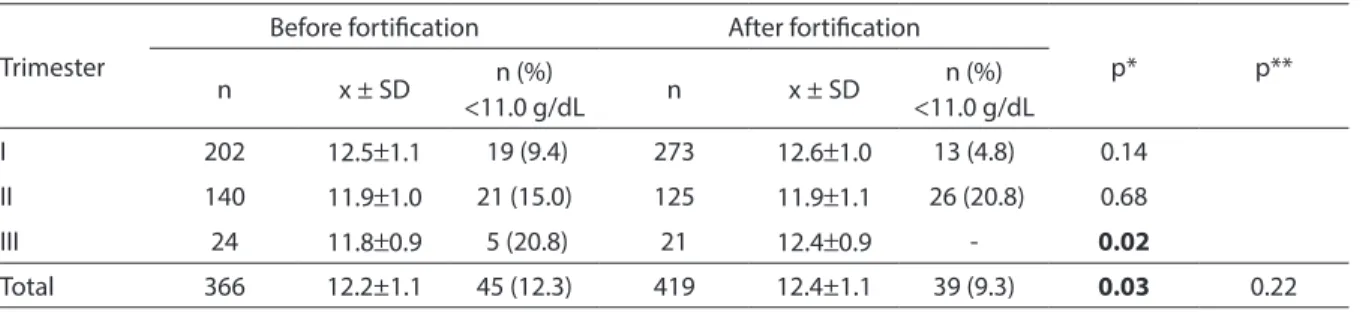

Mean Hb values differed significan-tly between Groups (p=0.03), although this difference referred to the third ges-tational trimester (p=0.02). Despite the frequency of anemia having been slightly lower in the After mandatory lour forti-ication group (9.3%), when compared to

Table 1 - Characteristics of pregnant second group before and after the mandatory fortiication of lour. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Tabela 1 - Características das gestantes segundo Grupos Antes e Após a fortiicação obrigatória das farinhas. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Variables

Before fortiication

n (%)

After fortiication

n (%)

p*

Age

< 20 years 64 (17.5) 80 (19.2) 0.60

≥ 20 years 302 (82.5) 337 (80.8)

Level of education

< 8 years 100 (29.0) 88 (23.6) 0.12

≥ 8 years 245 (71.0) 285 (76.4)

Employment

Unpaid job 156 (44.4) 158 (45.1) 0.91

Paid job 195 (55.5) 192 (54.8)

Marital status

Without a partner 94 (26.4) 136 (34.4) 0.02

With a partner 262 (73.6) 259 (65.6)

Beginning of prenatal care

1st trimester 202 (55.2) 273 (65.2) 0.02

2nd trimester 140 (38.2) 125 (29.8)

3rd trimester 24 (6.6) 21 (5.0)

Prenatal consultations

< 7 consultations 187 (51.9) 197 (47.2) 0.22

≥ 7 consultations 173 (48.1) 220 (52.8)

Nutritional status

Low weight 65 (21.0) 81 (22.9) 0.82

Adequate weight 152 (49.0) 167 (47.2)

Overweight/Obesity 93 (31.0) 106 (29.9)

Previous pregnancies

None 156 (43.5) 160 (41.0) 0.39

1 or more 203 (56.5) 239 (59.0)

the Before fortiication group (12.3%), this difference was not statistically signiicant. Nonetheless, high frequencies of anemia (20.8%) stood out in the second and third gestational trimesters of the After and Before mandatory lour fortiication groups, respectively (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the results of the multiple linear regression analysis. After adjusting for confounding variables, researchers observed that pregnant women of the After mandatory lour fortiication group had a mean Hb concentration that was 0.17g/dL higher than that of the Before fortiication group. Pregnant women with a paid job and a partner also showed higher Hb levels. Negative coeficients were identiied for the “gestational age in the irst consultation” and “number of previous pregnancies” variables, with significant decreases in Hb levels as the gestational age in the irst prenatal consultation and the number of

previous pregnancies increased.

Discussion

The assessment of the effect of programs and interventions must be performed ac-cording to pre-established goals, although such aspect is not usually included in the planning stage. Thus, an alternative to as-sess interventions is to compare results of prevalence surveys based on baseline data, when such are present in the beginning of the program, to subsequent indings15. Considering the fact that studies on the pre-valence of anemia among pregnant women in Brazil are restricted to speciic popula-tions, thus preventing the generalization of indings4, and that the city of Maringá, PR, does not have reference data, a before-and--after study was designed, including two independent groups of pregnant women.

The selection of pregnant women to

Table 2 - Mean of Hb and the proportion of pregnant women with anemia (Hb < 11.0 g / dL) second gestational trimesters and Groups Before and After the mandatory fortiication of lour. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Tabela 2 - Médias de Hb e proporção de gestantes anêmicas (Hb < 11,0g/dL) segundo trimestres gestacionais e Grupos Antes e Após a fortiicação obrigatória das farinhas. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Trimester

Before fortiication After fortiication

p* p**

n x ± SD n (%)

<11.0 g/dL n x ± SD

n (%) <11.0 g/dL

I 202 12.5±1.1 19 (9.4) 273 12.6±1.0 13 (4.8) 0.14

II 140 11.9±1.0 21 (15.0) 125 11.9±1.1 26 (20.8) 0.68

III 24 11.8±0.9 5 (20.8) 21 12.4±0.9 - 0.02

Total 366 12.2±1.1 45 (12.3) 419 12.4±1.1 39 (9.3) 0.03 0.22

* The p value refers to the t-Student test / *O valor de p refere-se ao teste t-Student

** The p value refers to Chi-square test / ** O valor de p se refere ao teste Qui-quadrado

Table 3 - Parameters of multiple linear regression for mean hemoglobin levels and studied variables. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Tabela 3 - Parâmetros da regressão linear múltipla para níveis médios de hemoglobina e as variáveis estudadas. Maringá, PR, 2007.

Variables β Standard Error p-value

After fortiication group * 0,172 0,081 0,034

Employment (has a paid job)* 0,231 0,080 0,004

Marital status (with a partner)* 0,306 0,089 0,001

Gestational age in the irst prenatal consultation -0,034 0,006 <0,001

Number of previous pregnancies -0,103 0,033 0,002

assess the effect of fortiication considered two aspects: the irst, already mentioned in the present study, is that the group analyzed is one of the most vulnerable to anemia; and the second, which enabled this study to be developed, is the fact that the prenatal care provided by public health services guaran-tees that a Hb test will be performed for all pregnant women having their irst prenatal consultation14. However, the dificulty in establishing the diagnosis of anemia du-ring pregnancy should be considered, as hemoglobin concentration changes with the hemodilution that occurs at this time in a woman’s life16. Based on such dificulty, hemoglobin levels were analyzed according to gestational trimester.

Although data was obtained from medical records, an aspect that should be taken into consideration due to quality of information, this method enabled the assessment of a great number of pregnant women. Consequently, the present study stands out because it provides a reference diagnosis of anemia in women cared for in public services of the city of Maringá, PR, and because it shows an evolution of this problem.

Data analysis showed that the two Groups of pregnant women studied were signiicantly different in terms of marital status and beginning of prenatal care. The proportion of pregnant women without a partner increased from one fourth in the Before mandatory lour fortiication group to one third in the After fortiication group. As the occurrence of anemia is dependent on negative socioeconomic-environmental conditions2,17 and women without a part-ner usually tend to have greater inancial dificulties, this difference could cause the After fortiication group to have a higher prevalence of anemia and lower Hb levels, although this was not observed here. The effect of lour fortiication remained, despite pregnant women with a partner having a mean Hb concentration that was 0.30g/dL higher than that of pregnant women without a partner in the multiple analysis, which controlled confounding variables.

With regard to the beginning of prena-tal care, it was observed that two thirds of pregnant women in the After fortiication group started it in the irst trimester, com-pared to half of the Before fortification group. This fact can partly explain the lower prevalence of anemia found in the After fortiication group, considering the inluence of gestational age on hemoglobin levels3. However, mean Hb levels did not differ in the irst and second gestational trimesters. Only in the third trimester were the means higher in the After fortiication group. With the adjustment of confoun-ding variables, the higher the gestational age in the irst prenatal consultation, the lower the mean Hb concentration, which decreased 0.03g/dL per week of gestation in the beginning of prenatal care. Thus, the higher proportion of pregnant women who began prenatal care in the irst trimester significantly affected the results of this study, whether these were higher mean Hb levels or lower prevalence of anemia in the After lour fortiication group. Despite the maintenance of the positive effect of forti-ication after controlling for confounding variables, it is important to consider the fact that other social policies implemented apart from lour fortiication, such as the income transfer programs which enabled an increase in the power of purchase of poorer families and greater access to food, health and sanitation, and that other varia-bles not analyzed in this study could have contributed to the more positive Hb levels observed in the results. These levels had a statistically signiicant variation, although slight and of low clinical relevance.

ranging between 5% and 20%, according to the classiication proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO)1. A recent study developed in the semi-arid region of the state of Alagoas found a prevalence of 50% of anemia in pregnant women18, while the prevalence observed in primary health units in the city of Cuiabá was 25.5%19, revealing a result that was very different from that found in Maringá. Thus, researchers conir-med the alarming results of anemia found by the PNDS5 in women of childbearing age, which affects 39% of this population in the Northeast region. In Mexico, although a re-duction has been observed, the prevalence of anemia in pregnant women remains at 20%20, indicating that this public health problem has not been resolved21.

The social determination of anemia in our environment has been well documen-ted in children22,23,24. In pregnant women, in the 1980s, this nutritional deiciency was associated with socioeconomic conditions that were characteristic of class situations25. Considering the fact that the South region shows the best social indicators when compared to the other regions26, the low prevalences of anemia found in this study conirm the inluence of such variables on the development of iron deiciency.

The possibility of these low prevalences of anemia preventing the effect of fortiica-tion from being observed should be taken into consideration, similarly to another study that also found a low prevalence of anemia in pregnant women cared for in a primary health unit of the city of São Paulo, before (9.2%) and after (8.6%) lour fortii-cation, without a signiicant difference27.

However, a study conducted with a population of pregnant women with a high prevalence of anemia observed a signiicant reduction in the rate of this disease, which decreased from 28.9% to 7.9%. According to the author, although the variables not investigated could have contributed to this result, mandatory fortiication was essential as there was a signiicant increase in mean iron intake by the pregnant women stu-died during the period immediately before

and one year after the implementation of mandatory lour fortiication with iron28. It should be emphasized that, although the Brazilian government regulated lour forti-ication in December 2002, it is possible that companies used the deadline of 18 months to regularize their status, so that fortiication actually became effective in July 2004, when it became mandatory11 .

However, this result was not observed in a study that assessed the effect of lour fortiication in children, even in a group with high prevalence of anemia, as this prevalence varied from 30.2% to

41.5% and subsequently to 37.1% in the three stages of the study: baseline, one year after the implementation of fortiication, and two years after this implementation, respectively24.

It should be emphasized that aspects associated with the pregnant women’s diet were not analyzed in the present study. Nonetheless, a study that assessed the intake of foods subject to mandatory fortiication with iron by pregnant women cared for in prenatal consultations showed that the iron intake did not meet the recom-mendation for this population30. Likewise, a study that assessed eating habits and the intake of food sources of iron, whether na-tural or fortiied, by women of childbearing age found that non-pregnant women met the iron requirement with the additional lour fortiication recommended, whereas pregnant women did not31. Thus, authors emphasized the need to promote other anemia prevention and control actions with lour fortiication.

irst trimester; from 9.2% to 43.9% in the second trimester; and from 10.9% to 52.3% in the third trimester4.

However, mean Hb concentrations differed significantly between Groups, decreasing with the development of the pregnancy in the Before mandatory lour fortiication group, but increasing in the last trimester of the After fortiication group. The fact that the mean Hb concentration of the After fortiication group was signiicantly higher in the third gestational trimester could suggest that this concentration was more influenced by gestational aspects inherent in the second trimester than by external factors, so that the positive effect of lour fortiication can only be observed in the last trimester.

Although there were no differences in the prevalence of anemia after adjustment for confounding variables, the results sho-wed the positive effect of lour fortiication on Hb levels, indicating an increase of 0.17g/ dL in the After fortiication group, compared to the Before fortiication group. This result was not observed in a similar study conduc-ted in the city of São Paulo22.

An association between Hb levels and the “employment” variable was observed, so that the mean Hb concentration of pregnant women with a paid job was 0.23g/dL higher than that of women who did not work. This variable did not differ between groups; however, this result suggests an association between anemia and social conditions2. In addition, the number of previous pregnan-cies had a signiicant negative effect on Hb, which was 0.10g/dL lower per additional previous pregnancy. This result corroborates those of other studies, which found lower Hb concentrations in pregnant women with a higher number of previous pregnancies32 and an association between anemia and a number of pregnancies higher than three33.

The results of the present study must be interpreted with caution, as many other variables may interfere with the occurrence of anemia, in addition to fortiication. Thus, it is recommended that other studies be developed.

Conclusions

Considering the fact that, in our en-vironment, data on anemia in pregnant women are accurate and show a great va-riation in different places, the present study stands out as it provides an important point of reference for the city of Maringá-PR in particular and for the country in general. The reason for this is that it assessed a representative sample of pregnant women cared for in all primary health units of this city.

The fact that this study analyzed he-moglobin levels and the occurrence of anemia, before and after the regulation of flour fortification, enables a baseline or reference diagnosis and the evolution of the problem at least one year after the effective implementation of the strategy. There were no differences in the low prevalences of anemia, both before and after lour fortiica-tion. These results are important and serve as positive feedback for the city’s public health services and health professionals who work there.

Despite the small variation in Hb levels found, which seems to have little meaning from a clinical perspective as the values were above the cut-off point for anemia, this difference was statistically signiicant and the Hb levels were higher in the After fortiication group. Consequently, even with the differences observed between groups, it is possible to assume that the lour fortiica-tion strategy has contributed to this result, although one should not ignore the contri-bution of other aspects not analyzed that were associated with different social policies implemented during this period. However, this result does not reject the importance of prenatal care and drug supplementation with ferrous sulfate during pregnancy.

conducted, using more extensive metho-dologies and aiming to effectively assess

the impact of lour fortiication on anemia control.

References

1. WHO-World Health Organization. Iron deficiency

anaemia – assessment, prevention and control: a guide

for programme managers. Geneva; 2001.

2. Batista M Filho, Souza AI, Bresani CC. Anemia como

problema de saúde pública: uma realidade atual. Ciênc

Saúde Colet 2008; 13(6): 1917-22.

3. Souza AI, Batista M Filho, Ferreira LOC. Alterações

hematológicas e gravidez. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter

2002; 24(1): 29-36.

4. Côrtes MH, Vasconcelos IAL, Coitinho DC. Prevalência de anemia ferropriva em gestantes brasileiras: uma

revisão dos últimos 40 anos. Rev Nutr 2009; 22(3):

409-18.

5. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Pesquisa nacional de

demografia e saúde da criança e da mulher PNDS 2006: Dimensões do processo reprodutivo e da saúde da

criança. Brasília (DF); 2009.

6. Uchimura TT, Szarfarc SC, Latorre MRDO, Uchimura NS,

Souza SB. Anemia e peso ao nascer. Rev Saúde Pública

2003; 37: 397-403.

7. Rocha DS, Pereira M Netto, Priore SE, Lima NMML, Rosado LEFPL, Franceschini SCC. Estado Nutricional e Anemia ferropriva em gestantes: relação com o peso da

criança ao nascer. Rev Nutr 2005; 18(4): 481-9.

8. Zimmermann MB, Hurrell RF. Nutritional iron

deiciency. Lancet 2007; 370(9586): 511-20.

9. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Programa de Assistência

Integral à Saúde da Mulher. Brasília (DF): Instituto

Nacional de Alimentação e Nutrição; 1982.

10. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde.

Departamento de Atenção Básica. Manual operacional

do Programa Nacional de Suplementação de Ferro.

Brasília (DF); 2005.

11. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária. Resolução - RDC nº 344, de 13 de dezembro de 2002. Aprova o Regulamento Técnico para a Fortiicação das Farinhas de Trigo e das Farinhas de Milho com Ferro e Ácido Fólico. Diário Oicial da União. 13 de dezembro de 2002.

12. Barros SMO, Costa CAR. Consulta de enfermagem a gestantes com anemia ferropriva. Rev. Latino-Am.

Enfermagem 1999; 7(4): 105-11.

13. Fujimori E, Laurenti D, Nunez de Cassana LM, Oliveira IMV, Szarfarc SC. Anemia e deiciência de ferro em

gestantes adolescentes. Rev Nutr 2000; 13(3): 177-84.

14. Ministério da Saúde (BR). Pré-natal e puerpério: atenção

qualificada e humanizada – manual técnico. Brasília

(DF); 2005.

15. Pereira MG. Epidemiologia: teoria e prática. Rio de

Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan; 2007.

16. Souza AI, Batista Filho M. Diagnóstico e tratamento das anemias carências na gestação: consensos e

controvérsias. Rev Bras Saúde Mat Inf 2003; 3(4): 473-9.

17. Silva SCL, Batista Filho M, Miglioli TC. Prevalência e fatores de risco de anemia em mães e ilhos no Estado

de Pernambuco. Rev Bras Epidemiol 2008; 11(2): 266-77.

18. Ferreira HS, Moura FA, Cabral Júnior CR. Prevalência e fatores associados à anemia em gestantes da região

semiárida do Estado de Alagoas. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet

2008; 30(9): 445-51.

19. Fujimori E, Sato APS, Araújo CRMA, Uchimura TT, Porto ES, Brunken GS et al. Anemia em gestantes de

municípios das regiões Sul e Centro-Oeste do Brasil. Rev

Esc Enferm USP 2009; 43 (n. esp 2): 1204-09.

20. Shamah-Levy T, Villalpando-Hernández S, García-Guerra A, Mundo-Rosas V, Mejía-Rodríguez F,

Domínguez-Islas CP. Anemia in Mexican women: results

of two national probabilistic surveys. Salud pública Méx

2009; 51(S4): 515-22.

21. Casanueva E, Regil LM, Flores-Campuzano MF. Anemia por deiciencia de hierro en mujeres mexicanas en edad

reproductiva: historia de un problema no resuelto. Salud

pública Méx 2006; 48(2): 166-75.

22. Fujimori E, Duarte LS, Minagawa AT, Laurenti D, Monteiro RMJM. Reprodução social e anemia infantil.

Rev. Latino Am Enfermagem 2008; 16(2): 245-51.

23. Leal LP, Osório MM. Fatores associados à ocorrência de anemia em crianças menores de seis anos: uma revisão

sistemática dos estudos populacionais. Rev Bras Saúde

Matern Infant 2010; 10(4): 417-39.

24. Leal LP, Batista Filho M, Lira PIC, Figueiroa JN, Osório MM. Prevalência de anemia em fatores associados em

crianças de seis a 59 meses de Pernambuco. Rev Saúde

Pública 2011; 45(3): 457-66.

25. Martins IS, Alvarenga AT, Siqueira AAF, Szarfarc SC, Lima FD. As determinações biológicas e social da doença: um

estudo de anemia ferropriva. Rev Saúde Pública 1987;

21(2): 73-89.

26. IBGE. Pesquisa Nacional por Amostra de Domicílios

2009. Disponível em http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/

27. Sato APS, Fujimori E, Szarfac SC, Sato JR, Bonadio IC. Prevalência de anemia em gestantes e a fortiicação de

farinhas com ferro. Texto Contexto Enferm 2008; 17(3):

481-9.

28. Côrtes MH. Impacto da fortificação de farinhas de trigo e

milho com ferro nos níveis de hemoglobina das gestantes atendidas pelo pré-natal do Hospital Universitário de

Brasília/DF [dissertação de mestrado]. Brasília (DF):

Universidade de Brasília; 2006.

29. Assunção MCF, Santos IS, Barros AJD, Gigante DP, Victora CG. Efeito da fortiicação de farinhas com ferro

sobre anemia em pré-escolares, Pelotas, RS. Rev Saúde

Pública 2007; 41(4): 539-48.

30. Vasconcelos IAL, Côrtes MH, Coitinho DC. Alimentos sujeitos à fortiicação compulsória com ferro: um estudo

com gestantes. Rev Nutr 2008; 21(2): 149-60.

31. Sato APS, Fujimori E, Szarfarc SC, Borges ALV, Tunechiro MA. Consumo alimentar e ingestão de ferro de gestantes

e mulheres em idade reprodutiva. Rev Latino Am

Enfermagem 2010; 18(2): 247-54.

32. Guerra EM, Barreto OCO, Vaz AJ, Silveira MB. Prevalência de anemia em gestantes de primeira consulta em centros de saúde de área metropolitana,

Brasil. Rev Saúde Pública 1990; 24(5): 380-6.

33. Vitolo MR, Boscaini C, Bortolini GA. Baixa escolaridade como fator limitante para o combate à anemia entre

gestantes. Rev Bras Ginecol Obst 2006; 28(6): 331-9.