w w w . e l s e v i e r . p t / r p s p

Special

article

Commentary:

Reducing

inequalities

in

child

obesity

in

developed

nations:

What

do

we

know?

What

can

we

do?

Nicholas

Freudenberg

CityUniversityofNewYorkSchoolofPublicHealth,HunterCollege,NewYork,UnitedStates

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:Received8September2012 Accepted23October2012 Availableonline26January2013

Keywords: Childobesity Healthinequalities Healthpolicy

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Inequalitiesinchildobesitywithinandamongnationsresultfromunequaldistribution ofresourcesandenvironmentsthatpreventunhealthyweightgain—healthyfood, oppor-tunities for physicalactivity,primary and preventivehealth care, and protectionfrom stressors.Whilesomedevelopednationshaverecentlyslowedtheincreaseinchild obe-sity,nonehassuccessfullyreversedthegrowingconcentrationofchildobesityamongthe pooranddisadvantaged.Thiscommentaryreviewstheevidenceonpatternsandcausesof unequaldistributionofchildobesityindevelopednationsandanalyzestheimplicationsfor thedevelopmentofinterventionstoreducetheseinequalities.

©2012PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.

Comentário:

Reduzir

desigualdades

na

obesidade

da

crianc¸a

em

países

desenvolvidos.

O

que

conhecemos?

O

que

podemos

fazer?

Palavras-chave: Obesidadeinfantil Desigualdadesemsaúde Políticasdesaúde

r

e

s

u

m

o

Asdesigualdadesnaobesidadeinfantildentrodecadaeentreosdiversospaísesresultam dadistribuic¸ãodesigualdosrecursosedeambientesqueprevinemoganhonãosaudável depeso:alimentossaudáveis,oportunidadesparaapráticadeatividadefísica,cuidados desaúdeprimáriosepreventivoseprotec¸ãodosfatoresdestress.Apesardealgunspaíses maisdesenvolvidosteremrecentementeconseguidodiminuiroaumentodaobesidadenas crianc¸as,nenhuminverteucomsucessoa concentrac¸ãocrescentedaobesidadeinfantil entreosmaispobresedesfavorecidos.Estecomentáriopretendereveraevidência exis-tentequeraoníveldospadrões,querdascausasdadistribuic¸ãodesigualdaobesidadenas crianc¸asempaísesdesenvolvidos,eanalisaasimplicac¸õesparaodesenvolvimentodas intervenc¸õescomvistaàreduc¸ãodessasdesigualdades.

©2012PublicadoporElsevierEspaña,S.L.emnomedaEscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.

Introduction

and

background

Childobesityisaprobleminitselfandaharbinger of seri-oushealth,social,andeconomicproblemsformanyoftoday’s

E-mailaddress:nfreuden@hunter.cuny.edu

overweightandobesechildren.Absenttransformative inter-ventionstoreducechildobesity,weriskleavingourchildren andgrandchildrenaworldinwhichtheirlifespansand qual-ityoflifeareworsethanforthecurrentgeneration,aterrible legacy. While increases in child obesity in recent decades

0870-9025/$–seefrontmatter©2012PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.

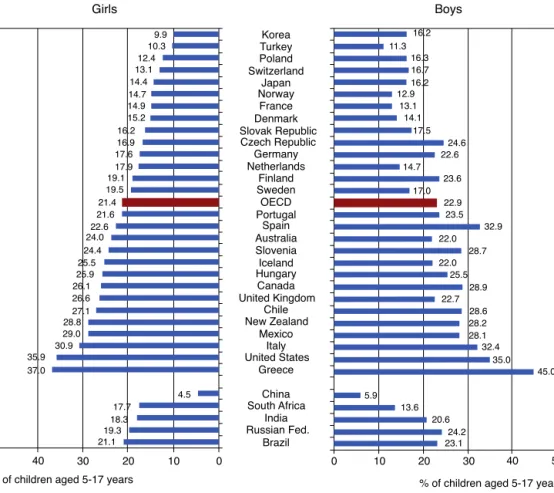

Children aged 5-17 years who are overweight (including obese), latest available estimates Girls Korea 9.9 16.2 11.3 16.3 16.7 16.2 12.9 13.1 14.1 17.5 24.6 22.6 14.7 23.6 17.0 22.9 23.5 32.9 22.0 28.7 22.0 25.5 28.9 22.7 28.6 28.2 28.1 32.4 35.0 45.0 5.9 13.6 20.6 24.2 23.1 10.3 12.4 13.1 14.4 14.7 14.9 15.2 16.2 16.9 17.6 17.9 19.1 19.5 21.4 21.6 22.6 24.0 24.4 25.5 25.9 26.1 26.6 27.1 28.8 29.0 30.9 35.9 37.0 4.5 17.7 18.3 19.3 21.1 50

% of children aged 5-17 years % of children aged 5-17 years

Source: International Association for the Study of Obesity (2011).

Statlink: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/888932523994 50 40 30 20 10 0 0 10 20 30 40 Turkey Poland Switzerland Japan Norway France Denmark Slovak Republic Czech Republic Germany Netherlands Finland Sweden OECD Portugal Spain Australia Slovenia Iceland Hungary Canada United Kingdom Chile New Zealand Mexico Italy United States Greece China South Africa India Russian Fed. Brazil Boys

Fig.1–Childrenaged5–17yearswhoareoverweight(includingobese),latestavailableestimates.

haveaffected allsocial classes,countriesand cultures,the burdenofobesityanditslifetimeadverseconsequencesare notequallydistributed.Healthofficials,healthprofessionals, researchersandpolicymakersinmanycountrieshavecalled forcomprehensiveactiontoreducetheratesofchildobesity butlessattentionhasbeenfocusedonactingtoreducethe wideandgrowinginequalitiesinchildobesity.

Giventhe risingratesofdiet-related non-communicable diseasesinlow,middleandhighincomenations,anyfailure tomakeinequalityreductionaprioritywillwidenthealready largesocioeconomicandracial/ethnicgapsinoverall prema-turemortalityandpreventableillnesses.Thus,takingaction toreduceinequalitiesinratesofchildobesityisanessential componentofachievingnationalandglobalgoalsofachieving healthequality.

In this commentary, I review what is known about the scope,magnitudeanddistributionofchildobesitywithafocus ondevelopednations;summarize the currentliteratureon its causes; and then analyze the options for interventions toreduce inequalitiesin childobesity. The broader goal is toinform the developmentof moreeffective interventions toreducing inequalities in childobesity. Given risingrates ofchildobesityinmiddleincomeandemergingnations,the experiencesinoftheUnitedStates,Europeandotherwealthy countriesmayprovideinsightsthatcanhelpothercountries avoidsomeofthegrowingburdenofchildobesity.

The

scope,

magnitude

and

distribution

of

inequalities

in

child

obesity

Inthelastfewyears,severalreviewshavesummarizedwhat isknownaboutthedistributionofchildobesitywithinand betweennations.AnupdatefromtheOrganizationfor Eco-nomicDevelopment,asshowninFig.1, reportsthat for5– 17 years oldgirls,the latestdataavailableshow thatrates ofoverweight (includingobesity)range from4.5percentin Chinato37percentinGreece;forboysaged5–17therange is5.9percentalsoinChina,to45percentinGreece.1Ofthe

33 countriesforwhichdataare reported,15 nationsreport rates of overweight of more than 20 percentfor girls and 20nationsreportratesofoverweightofmorethan20percent forboys.Inmostcountries,theOECDreportshows,boysaged 5–17havehigherratesofoverweightthangirls.InEngland, FranceandtheUnitedStatesbutnotinKorea,childrenshow socialinequalitiesinoverweightrates.Thereportconcludes that forchild obesityas well asadultobesity, “there isno clear sign of retrenchment ofthe epidemic, despitemajor policyefforts focusedonchildreninsomeofthe countries concerned.”1(p.1)

In a study analyzing the relationship between income inequality and obesity in 19 European and North Ameri-can countries, Wilkinson and Pickettt found that that for

13–15 year olds, developed nations with higher levels of incomeinequality havehigher rates of obesity among13– 15years.2(p.93)Atthehighendoftheincomeinequality/teen

obesityassociationweretheUSA,PortugalandtheUK;atthe lowendwereSweden,FinlandandNorway.Similar relation-shipswerefoundforadultwomenandmen.3

Thesenationalratesmasksubstantialdifferenceswithin nations.InChina,forexample,citiessuchasShanghaiand Beijingreportdramaticallyhigherratesofchildobesitythan doinlandcitiesorruralareas.4Todate,thesocialgradientin

childobesityinChinadoesnotfollowpatternsinobservedin mosthigherincomenations.

Several studies have examined demographic correlates of child overweight in Europe. For example, one study of preschoolchildrenaged4–7insixnations(Germany,Belgium, Bulgaria Greece,Poland, and Spain) found that childrenof parentswithhigh body mass index(BMI) or low socioeco-nomicstatuswereathigherriskofoverweightandobesity thantheirrespectivecounterparts.5 Parentalinfluencescan

begenetic,metabolic(e.g.,overweightmothersarelesslikely tobreastfeed),behavioral,orenvironmental(e.g.,lowincome parentsaremorelikelytoliveinmoreobesogenic commu-nities). Another review ofEuropean studies on differences inoverweightamongchildrenfrommigrantandnative ori-gin found that migrant children, especially non-European migrants,wereathigherriskforoverweightandobesitythan theirnativecounterparts.6

In the United States, a recent reviewfound “persistent andhighlyvariable disparitiesinchildhoodoverweightand obesity within and among states, associated with socio-economic status, schooloutcomes, neighborhoods, type of health insurance, and quality of care”.7(p.347) According to

theNationalSurveyofChildren’sHealth,Black,Hispanicand PacificIslanderchildrenaged10–17yearsold haveratesof overweightandobesitysubstantiallyhigherthanwhiteand Asianchildren.8Thesedifferencesinobesityratesalsotrack

differences in householdincome and educational achieve-ment byrace/ethnicity, showingthe clustering ofdifferent formsofinequality.Obesity andoverweight are also corre-latedwithparentaleducationwithchildrenofparentswith lesseducationhavinghigherratesthanchildrenofmore edu-catedparents.From2003to2007,obesityprevalenceforall 10–17yearoldsincreasedby10percentbutforchildrenin low-education, incomeor unemploymenthouseholds by 23–33 percent.9 Children with public insurance, single mothers,

livinginHispanicSpanish-languagehousehold,andin neigh-borhoodswithnoparkorrecreationcenterhavehigherrates of obesity/overweight than their respective counterparts.7

Anotherreviewreportedthatseveralstudiesfound substan-tial differences inthe distribution of early liferisk factors forchildobesitysuchasinfantfeedingpractices,sleep dura-tion, child’s diet, and patterns of physical and sedentary activities.10

Dothesesocioeconomic,racial/ethnicandgender dispar-ities in rates of child obesity constitute an injustice? The theories of philosophers Amartya Sen, Martha Nussbaum and others suggest they do.11,12 In this view, social

con-ditions that deprive one sector of the population of the opportunitytoachievetheirfullpotentialforwell-beingand fullparticipation insociety are unjust. Clearly, the health,

socialand economic consequencesofchild obesityburden individuals,familiesandcommunitiesforlife.Thus,the dif-ferential distribution of the conditions that contributes to obesityservetomaintainorexacerbatethesocialandhealth inequalitieswithinandamonglow,middleandhighincome nations.13

Drivers

of

inequality

of

child

obesity

Public policy discussionsabout obesity often failto distin-guishbetweendriversofobesity(i.e.,prevalence)anddrivers ofinequalitiesinobesity(i.e.,disparitiesorinequalities).Most basically,theprevalenceofobesitywillincreasewhengrowing proportionsofthepopulationincreaseconsumptionofhigh calorie,lownutrientfoodsanddecreasethephysicalactivity neededtoburnthesecalories.Thisdescribesthesituationin mostoftheworldtoday.

However,inequalities inhealth– and obesity– are pro-duced when healthy and unhealthy living conditions and opportunity structures are differentially distributed among thepopulationsofdifferentnations,regionsorlocalities, lead-ing to differences in the rates of increase in obesity and thereforeinequalities initsdistribution. Thusitispossible toreducethe prevalenceofobesitywithout addressingthe distribution.

Many national and municipal governments are taking actiontoaddressthemaindriversofelevatedBMIsbutfew areactingaggressivelytochangethedistribution.Theresult ofsuchpoliciescanbethatthebetteroffbenefitmorefrom interventionsthanthepoor,thusactuallywideningthegap. Forthoseseekingtoreducethehealthburdenofchildobesity, finding ways tochange the distribution ofobesogenic envi-ronmentsisasimportantasreducingtheprevalenceinthe populationasawhole.

In both the United States and Europe, child obesity is becoming concentrated inlow incomecommunities.Given its role inthe etiologyofnon-communicablediseases, this suggests a vicious circle of increasing concentration of childobesity,earlyonsetofnon-communicablediseasesand wideningsocioeconomicinequalitiesinprematuremortality andpreventableillness.

Differentialdistributionofthreeresources–food,physical activityopportunities,andhealthcare–hasbeenidentified asmaindriversofinequalitiesinchildobesity.14These

fac-torsoperateattheglobal,national,regional,communityand individuallevelstoproducedifferingratesofobesityamong differentsocialgroups.Tosummarize,marketforces,public policiesandsocialfactorsinteracttodifferentiallydistribute accesstoaffordablehealthyandunhealthyfood, opportuni-tiesforsafephysicalactivity,andaccesstotheprimaryand preventivehealth servicesthat canreducethe riskof obe-sity. ThisdifferentialdistributionofwhatSwinburnetal.15

andothers havelabeled“obesogenicenvironments”creates inequalitiesinchildobesity.

WilkinsonandPickett2proposeafourthdriverfor

inequal-ities in obesity: social stressors associated with the social gradient and income inequality.They arguethat “the psy-chosocialeffectsofinequalitymaybeparticularlyimportant becausetheycaninfluenceallotherpathways:sedentarism,

caloric intake, food choice and the physiological effects of stress.”3(p 673) They fault the more behavioral

explana-tions of obesity for their failure to address “the reasons why people continue to live a sedentary lifestyle and to eat an unhealthy diet, and how these behaviors provide comfort.”

Driversofinequalitiesinchildobesitycanbeconsidered the “cause of the causes”,16 the underlying determinants

of the multiple social and behavioral correlates of higher BMIs.Understandingtheprecisemechanismsbywhicheach ofthesedriversoperates ateach leveloforganization ata particulartimeandplaceisacriticalfirststepineliminating inequalitiesinchildobesity.Rankingthecausalimportance andthefeasibilityofchangeateachlevelforeachdriveris asecondcriticalstep.Thisanalysiscanleadtoprioritiesfor action.Basedonsuchanalyses,healthofficialsandpolitical leaderscangivethemostattentiontothemosteffectiveand feasiblepolicies,programsandservices.Thisapproachhasthe potentialtomakemeaningfulchangesinthemostpowerful causalpathways.

Health inequalities intersect with and are produced by other formsof inequality such as income, education, and transportation inequalities, creating a cascade of inequali-tiesthatoperateacrossgenerations.Forexample,inadequate schoolingdeprivesparentsoftheknowledgeandskillsto pro-tecttheirchildrenagainstobesityandtheincometoafford healthierfood andmoreopportunitiesforphysicalactivity. Low-incomeneighborhoodsmaylackhealthierfoodchoices andalsothetransportationsystemsthatwouldmakeiteasy forresidents totravelto supermarkets outside the neigh-borhoodthatdoofferhealthier food.Higher ratesofcrime in low-income neighborhoods may dissuade parents from encouragingtheirchildrentoplayoutside,thusfurther expos-ingthemtolongerhoursoftelevisiontime,itselfassociated withsedentarismandunhealthydiets.Moreover,the cumu-lativeburdensofpovertyandinequalitycreatestressorsthat cascadedownthesocialgradient,concentratingamongthe poorest.Aspreviouslydescribed,theseaccumulating stress-orscanincreasebehaviorsassociatedwithobesity.Toreduce inequalitiesinchildobesity,we’llneedtofindnewwaysto interruptthiscascadeatvariouslevelsoforganization.Thus, intersectoralapproachesthatincludefood,education, crim-inaljustice,andtransportationsectorsareakeyelementof effectiveresponses.17

Interventions

to

reduce

child

inequalities

Giventhecomplexityofthepathwaysandmechanismsthat shapetheprevalenceanddistributionofchildobesityno sin-gle intervention can reverse the trends of the last two or threedecades.Rather,healthauthoritiesatalllevelsof gov-ernment,inpartnershipwithothergovernment,civilsociety andbusinesssectors,willneedtocreateaportfolioof pol-icy,programmaticandeducationalinterventions.Mappingthe systemsthatcontributetoinequalitiesinchildobesityandthe relativecontributionsofsingleandmultipledeterminantswill helptosetprioritiesforaction.

Severalrecentreviewssummarizetheavailableevidence oninterventionstoreducechildobesity.14,18,19Several have

focusedspecificallyon policyinterventionsand dissemina-tionandsustainabilityissues.20–24Theinterventionsshownto

beeffectiveconstitutethebuildingblocksforthemulti-level, multi-sectorportfoliosofinterventionsthatwillbeneededto reducechildobesity.Twokeypointsshouldinformthe cre-ationofthesemorecomprehensiveresponses.First,reducing the unequaldistributionofchildobesityamongpopulation groupsrequiresunderstandingandaddressingthepreviously describeddriversofinequalities,notsimplyitsindividuallevel determinants. Second, a portfolio of interventions, like an investmentportfolio,must bebalancedamongsectorsand between long and short term and high risk, high payoff andlowerriskbutlowerpayoffapproaches.New methodolo-gieslikeportfolioreview25,26 andsystemsscience,27–29 both

stillinearlystagesofdevelopment,willneedtobeappliedto thistask.

The literature on child obesity and more broadly on healthinequalitiessuggestsseveralinterventiondimensions that portfolioplannersshouldconsider.Theseover-lapping but conceptuallydistinct dimensionsare bestconceivedas continua rather than dichotomies. The five I will briefly consider here are: upstream vs. downstream; targeted vs. universal;localvs.national;educationvs.regulation;and vol-untary vs. mandatory. The taskfor plannersis toselect a portfolioofinterventionsthatincludeanappropriatebalance ofthesecharacteristics.

Upstreamvs.downstream:Changedriversofinequalities

Upstream interventions to reduce child obesity tackle the social forces that push some populations into social cir-cumstancesthatelevatetheriskforobesityandthatcreate obesogenicenvironments.Downstreamonesseektomitigate theconsequencesoftheseenvironments.Upstream interven-tionstoshrinkinequalitiesinchildobesitywithinoramong nations seek to modify the social forces that inequitably distribute poverty,marginalization,cumulativeexposureto stressors,accesstohealthyfood,exposuretounhealthyfood marketing,opportunitiesforphysicalactivityandaccessto theprimaryandpreventivehealthservicesthatcanreduce childobesity.

Examplesofupstreaminterventionsincludetax,workand socialbenefitspoliciestoreduceincomeinequality,poverty, andsocialmarginalization,allfactorsrepeatedlyassociated with inequalities in child obesity. They also include trade agreementsandregulationsthatlimittherightsofthefood industrytoproduceandmarketunhealthyfoodtochildren, often targeting low income populations.30,31 Downstream

interventionstoreduceinequalitiesprovidepopulations expe-riencing higher rates of obesity with enhanced access to services and programs designed to reduce obesity at the individual level.Morebroadly, PaulFarmerhaslabeled this strategy the “preferentialoption forthe poor”, basing it in part on Christiantheology.32 By givingpopulations of

chil-dren mostexposed tothe socialfactors thatcause obesity firstoptionsforhealthierfood,moreopportunitiesfor phys-icalactivityandenhancedaccesstopreventiveandprimary healthcare,healthauthoritiescanbegintowhittleawaythe handicapsimposedbylivinginamoreriskyenvironment.

Targetedvs.universal

Targetedinterventionstoreducechildobesityfocuson popu-lationsathighestriskwhileuniversalonesprovidebenefitsto theentirepopulation.Toillustrate,somenationsand munici-palitiesprovidefree,healthyschoolmealstoallchildrenwhile others limit this offer only tothose livingin poverty. The firstapproachhastheadvantageofnormalizingthebenefit andreducinganystigmaassociatedwithfreeschoolfood.In practice,itoftenbenefitsthepoormost,becausetheyhaveless accesstohealthyfood outsideschools. Universalprograms alsowinpoliticalsupportfromallsectorsofthepopulation, makingthemlesssubjecttocutbacksintimesofeconomic decline,preciselywhentheyaremostneeded.

Targeted approaches are less expensive and focus resourcesonthose mostinneedbutare especially vulner-able during periodsof austerity. Targeted approaches may alsomagnifydiscriminationorsocialisolation.33Other

exam-plesoftargetedapproachesaredistributinghealthyfoodin poorcommunities,zoningrestrictions onfastfood inhigh obesityorhigh poverty neighborhoods,nutritioneducation inlow incomecommunities,and newparks inhigh crime areas.Universalapproachesincludelimitsonfoodadvertising tochildren,calorielabelinginrestaurantsandfastfood out-lets,mandatedandenforcedphysicalactivityinallschoolsor progressivetaxestoreverseincomeinequality.Both univer-salandtargetedapproachescancontributetoreductionsin inequalitiesinchildobesity.

Educationvs.regulation

Athirddimensionofinterventions isthe balance between educationandregulation.Educationalinterventionsarebased onthediagnosisthatindividualslackinformation,knowledge orskillstoavoidobesity;theprescriptionistoprovidelearners withthemissingingredient.Regulations,ontheotherhand, diagnosetheproblemswithininstitutionsandorganizations andprescribestate-mandatedorganizationalchangeasthe remedy.

Inpractice,thetwoapproaches canbecombined. Inter-ventionstooffercaloriepostingandnutritionlabelsonfood, forexample,mandate commercial outletstoprovidethese services to individuals, who will presumably make more informed choices based on this information. In addition, studiesshowthatcalorielabelingmayleadorganizationsto reformulateproducts,anorganizationalchange.34Campaigns

toeducate womenaboutthe benefitsofbreastfeedingand therisksofinfantformulaandtoimprovenutrition educa-tioninthe schoolsare educationalapproaches.Endingthe distributionoffreeinfantformulainhealthsettings,banning thepromotion ofobesogenic foodstochildren,and setting standardsonfoodportionsizeandnutrientdensityillustrate aregulatoryapproach.Ingeneral,regulatoryapproachesare moreefficientthaneducationbecausetheybypassthe diffi-culttaskofchangingmanyindividuals.However,regulations alsoelicitmorepoliticaloppositionfrominterestgroupswho maylose profitsasaresult.Regulatoryapproachesmay be moreeffectiveinreachingvulnerablepopulations,whomay lackthetime,resourcesorprioreducationalbackgroundto takefulladvantageofeducationalinterventions.

Localvs.national

Afourthdilemmafacingplannersseekingtoreducechild obe-sityishowtofindtherightbalancebetweenworksatthelocal versustheregionalornationallevels.Driversofprevalence andunequaldistributionoperateatallthreelevelsand juris-dictionsvaryinhowresponsibilitiesforfood,physicalactivity and healthcarepoliciesare allocated.Ingeneral,operating athigherlevelsoforganizationismoreefficient,asasingle policy change canbenefitthe country as awhole. Inlarge countries,however,nationalgovernmentsmayhavedifficulty inimplementingpoliciesnationwideandlocalorregional gov-ernments may resistnational mandates, especially if they arenotgivenadequateresourcestofulfilltheseobligations. National policiesmayalsogeneratehigherlevelopposition fromspecialinterestgroups,e.g.,thefoodindustry,making policychangemoredifficult.

Insomecases,localchangescansetthestagefornational ones. In the United States, forexample, several cities and statesrequiredcalorielabelinginfastfoodchainrestaurants, apolicythatthenbecamepartofthenationalAffordableCare Act.35Somelocalpoliciesthatmaycontributetoreductions

ininequalitiesinobesityareeffortstosubsidizesuper mar-kets and other stores that sellhealthy foods in poorarea; improvedaccesstobicycling,walkingandmasstransit,rather thanautomobiletravel;localinitiativestosupporturban agri-culture; and municipal taxes on sugarybeverages orother unhealthyproducts.Nationalpoliciesmaybemore appropri-ateforfunctionsthatusuallyoperateonlyatthenationallevel: rulesforfoodadvertisingtochildren,nationalstandardson sugarandfatforfoodformulation,andhealthcare reimburse-mentfornutritioncounseling.

Both local and national interventions can contribute to reductionsininequalitiesinchildobesity.Perhapsthe great-estriskforlocalapproachesistofallintothe“localtrap”36in

whichlocalauthoritiesassumethatfactorsdriving inequali-tiesinchildobesitycanbefullyaddressedatthelocallevel wheninfacttheyaregeneratedandoperateatalllevels.

Voluntaryvs.mandatory

A fifth dimension to consider is voluntary approaches, in which companies and other organizations are encouraged tochangeobesogenicpracticesversusmandatoryones (usu-allygovernmentregulation)thathavethepowerofthestate behindthem.

The rationale forvoluntary approaches isthat they tap intotheexpertiseoftheorganizationsthatneedtomakethe changes(e.g.,thefoodindustryinformulationoffood prod-uctsforchildren);donotrequireanextensiveenforcement apparatus;anddonotunnecessarilyextendthepowerof gov-ernment.Theproponentsofregulatoryapproachesrespond that empirical investigations of voluntary standards often showlimitedeffectiveness,adherenceisdifficulttoestablish, and that theycede avitalpublic role inprotecting health. Inpractice,asshownrecentlyintheUnitedStates,despite lipservicetovoluntaryapproachestolimitingmarketingof unhealthyfoodtochildren,thefoodindustryoftenopposes evenvoluntarystandards.37

Arelateddebateistodeterminetheappropriaterolefor special interests in setting obesity policy. Thefood indus-try has called forpublic private partnerships toset policy whilesomeadvocatesandresearchershavearguedthatthis presentsinherentconflictsofinterestsincefoodcompanies are legally required to maximize profits, not protect child health.38Theseadvocates suggestpublichealth

profession-alsandfoodcompaniescannegotiateagreementsbutneedto acknowledgetheirsometimesconflictinginterests,not pre-tendthatallshareacommongoal.

Towardtransformativepoliciesandprograms

Beyond these five dimensions of interventions to reduce inequalitiesinchildobesityisabroaderclashbetweenthose whoadvocateincrementalandtransformativechangesinour approachtochildobesity.Intherealworld,arguethe incre-mentalists,onlymodestchangeispoliticallyfeasible;reducing foodintakebya50–100caloriesadayorincreasingdaily phys-icalactivityby10minissufficient,ifsustainedtobringabout measurabledeclinesinobesity.Adoptingthelanguageofharm reduction,proponentsofincrementalchangeargueitisbetter tomakesmallchangesthannoneatall.Theyalsoclaimthat incrementalchangescanleadtoa“tippingpoint”inwhich littlechangessnowballintomoremeaningfulones.

Transformativereformersrespondthattodatethe mod-estchangesinpoliciesandprogramsrelatedtochildobesity havenotledtoreversalsoftheprevalenceordistributionof childobesity,eveninplaceswithmorecomprehensive pro-grams.Theyalsoworrythatincrementalchangesmayco-opt thedemandformoremeaningfulchange.

Windows

of

opportunity:

Trapdoors

of

risk

Inthelastdecade,theproblemofchildobesityhasattracted growingattentionfrompolicymakers,themedia,health offi-cials and others. International organizations, national and municipalgovernmentsandcivilsocietygroupshavemade the reductionofchild obesitya muchhigher prioritythan inthe past.Somerecentevidencesuggests thattherateof increasehasslowedorperhapsstabilizedinsomecountries, apositivedevelopment.Butasyetreductionsininequalities inchildobesity havenot beendocumented, and infact in someplaces continuetowiden. Tochange this distressing realitywillrequireidentifyingnewwindowsofopportunity forchangeaswellasemergingtrapdoorsthatcanjeopardize possiblesuccesses.Byseizingtheformerandavoidingthe lat-ter,itmaybepossibletocreatepoliciesthatcanshrinkcurrent inequalitiesinchildobesity.

Windowsofopportunity

Astheeconomiccrisisof2008hasfurtherwidenedalready high levels of income inequality in developed nations, a growingchorusofcriticshaspointedoutitsadversemoral, political,socialandeconomicconsequences.2,39,40Thiswider

awarenessofinequalitypresentspublicofficialsand health authoritieswithanopportunitytoproposestructuraland pol-icysolutionsandtocontesttheausterityalternative,described

inthenextsection.IntheUnitedStates,Europeandaround theworld,electedleaders,socialmovements,andgrassroots mobilizationsaredemandingthatpolicymakerstakeactionto reduceinequalities.Specifyingtheobesityandhealth-related costsinducedbyrisinginequalitycanquantifythe opportu-nitycostsofnotactingtoreduceinequality.

Similarly, child obesity and especially the adult obesity and chronic diseases thatinevitably follow it contributeto therisingcostofhealthcare.TheUnitedStates,theUnited Kingdomandothernationsarestrugglingtore-organizetheir healthcaresystemstomaintainqualitywhileloweringcosts. In this climate,shrinking the flow ofdiet-related diseases intohealthcaresystemisapromisingstrategyforlowering costs. Reducingobesity prevalencebydevelopingstrategies thatmostbenefitlow-incomechildrenhasseveraleconomic benefits:comparedtoadultstrategies,itmaximizes opportu-nitiesforcost-savingprevention;itimprovesthehealthofthe low-incomepopulationsmostlikelytodependonpublic fund-ingfortheirhealthcare,eveninhealthsystemsthathavea strongpublicsector;anditbenefitsmostthedisadvantaged populationsmostlikelytohaveahighburdenofothercostly healthproblems.

Anotheropportunityforlinkingeffortstoreduce inequali-tiesinchildobesitywithotherpubliceffortsisthegrowing global movement to controlnon-communicable diseases.41

Child obesityisakeydriverofrisingrates ofNCDsinlow, middleandhighincomenations;reducingitsincidenceand its unequal distribution is a prime strategy for achieving the global goal of reducing the burden of NCDs. A recent WHOreportforEuroperecognizestheimportanceof reduc-inginequalitiesinchildobesityaspartofaEuropeanstrategy forthepreventionandcontrolofNCDs.42

Finally,thegrowthofafoodjusticemovement,initiallyin developednationsbutnowaroundtheworld,canbecomean importantallyforthepolicychangesneededtoreducethe prevalence and unequal distribution ofchild obesity.43,44,45

Afoodjusticemovementthatunderstandsandcanexplain the linksbetweenobesity, foodinsecurity, noncommunica-blediseaseepidemics,climatechangeandunsustainablefood systems can bea powerfulforce for change, acatalystfor mobilizationatthecommunity,regional,nationalandglobal levels.

Trapdoorsofrisk

Thecurrentmomentalsopresentschallengesthatcan under-mineanyprogressinreducinginequalitiesinthedistribution ofchildobesity.Mostdramatically,theausterityideologythat hasemergedinresponsetothe2008globaleconomiccrisis threatens todeprivegovernmentsofthefundingand man-datetoactaggressivelyagainstchildobesity.46,47Asrestoring

economicgrowth andfreeingmarket forcesbecomehigher prioritiesthanreducinginequalityorimprovinghealth,many governmentsupportedprogramscreatedinordertoreduce childobesityoritsfundamentaldriversareatriskofcutbacks or elimination. At the same time, multinational corpora-tionsandtheiralliesargueforderegulationandprivatization, deprivinggovernmentsoftheregulatorytoolsneededto pro-tect childrenfromaggressivemarketingofunhealthy food. IntheUSandtheUK,foodcorporationsandsomepolitical

leadersareproposingtoturnovermoreresponsibilityfor stan-dardsforhealthyfoodtothefoodindustryitself,amovethat promisesmore,notlesschildobesity.37,38

Conclusion

Continuing increases in child obesity and the persistent inequalitiesinitsdistributionthreatenpopulationhealthand socialjusticeinlow,middleandhighincomenations.While moreresearchisneededonthecausesandconsequencesof inequalitiesinchildobesity,forthemostpart,weknowwhat needstobedone.Theeconomicandpoliticalforcesthatcreate moreobesogenicenvironmentsforallpeople,butespecially thoselivingatlowerlevelsofthesocialgradient,needtobe confronted.Nosingleinterventionwillachievetheseresults. Butbydevelopingaportfolioofpolicies,programsand ser-vicesthatcantransformthefood,physicalactivityandhealth careenvironmentsthat contributetothe increasing preva-lenceandunequaldistributionofchildobesity,wecanbegin toreversethealarmingtrendsofthelastthreedecades.

Atthesametime,bymitigatingthesocialstressorsthat accumulateamongthoselivingloweronthesocialgradient andthatalsoincreasetheirriskforobesity,wecan acceler-atethatreversal.Whatisneededisnotmoreevidencebut thepoliticalwillandthemobilizationthatwillbeneededto makethatchange.Fortunately,thistypeofchallengeisone thatpublichealthanditsallieshavemetmanytimesbefore. Whatremainstobedoneistotranslatethelessonslearned fromourpastsuccessestothetaskathand.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorhasnoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. OrganizationforEconomicDevelopment.Obesityupdate2012 [Internet].Paris:OECD;2012[cited2012Apr12].Availableat:

http://www.oecd.org/els/healthpoliciesanddata/49716427.pdf

2. WilkinsonR,PickettK.Thespiritlevel:whymoreequal societiesalmostalwaysdobetter.London,UK:AllanLane; 2009.

3. PickettKE,KellyS,BrunnerE,LobsteinT,WilkinsonRG. Widerincomegaps,widerwaistbands?:anecologicalstudy ofobesityandincomeinequality.JEpidemiolCommunity Health.2005;59:670–4.

4. ChenCM.OverviewofobesityinMainlandChina.ObesRev. 2008–2009;Suppl.1:14–21.

5. VanStralenMM,teVeldeSJ,vanNassauF,BrugJ, GrammatikakiE,MaesL,etal.WeightstatusofEuropean preschoolchildrenandassociationswithfamily demographicsandenergybalance-relatedbehaviors:a pooledanalysisofsixEuropeanstudies.ObesRev.2012;13 Suppl.1:29–41.

6. LabreeLJ,vandeMheenH,RuttenFF,FoetsM.Differencesin overweightandobesityamongchildrenfrommigrantand nativeorigin:asystematicreviewoftheEuropeanliterature. ObesRev.2011;12:e535–47.

7. BethellC,SimpsonL,StumboS,CarleAC,GombojavN. National,state,andlocaldisparitiesinchildhoodobesity. HealthAff(Millwood).2010;29:347–56.

8.USDepartmentofHealth,HumanServices,HealthResources, ServicesAdministration,Maternal,ChildHealthBureau.The NationalSurveyofChildren’sHealth2007.Rockville,MD:U.S. DepartmentofHealthandHumanServices;2009.

9.SinghGK,SiahpushM,KoganMD.Risingsocialinequalities inUSchildhoodobesity,2003–2007.AnnEpidemiol. 2010;20:40–52[Erratumin:AnnEpidemiol.2010;20:250]. 10.DixonB,Pe ˜naMM,TaverasEM.Lifecourseapproachto

racial/ethnicdisparitiesinchildhoodobesity.AdvNutr. 2012;3:73–82.

11.SenA.Whyhealthequality?In:AnandS,PeterF,SenA, editors.Publichealth,ethicsandequity.Oxford,UK:Oxford UniversityPress;2004.p.21–33.

12.NussbaumMC.Womenandhumandevelopment:the capabilitiesapproach.Cambridge,UK:CambridgeUniversity Press;2000.

13.BlacksherE.Children’shealthinequalities:ethicaland politicalchallengestoseekingsocialjustice.HastingsCent Rep.2008;38:28–35.

14.KulpersYM.Focusingonobesitythroughahealthequitylens. ObesRev.2012;13Suppl.1:29–41.

15.SwinburnB,EggarG,RazaF.Dissectingobesogenic environments:thedevelopmentandapplicationofa frameworkforidentifyingandprioritizingenvironmental interventionsforobesity.PrevMed.1999;29:563–70. 16.MarmotM.Socialdeterminantsofhealthinequalities.

Lancet.2005;365:1099–104.

17.LoureiroMI,FreudenbergN.Engagingmunicipalities incommunitycapacitybuildingforchildhoodobesitycontrol inurbansettings.FamPract.2012;29Suppl.1:i24–30. 18.SummerbellCD,MooreHJ,VögeleC,KreichaufS,Wildgruber

A,ManiosY,etal.Evidence-basedrecommendationsforthe developmentofobesitypreventionprogramstargetedat preschoolchildren.ObesRev.2012;13Suppl.1:129–32. 19.WatersE,deSilva-SanigorskiA,HallBJ,BrownT,CampbellKJ,

GaoY,etal.Interventionsforpreventingobesityinchildren. CochraneDatabaseSystRev.2011:CD001871.

20.BrennanL,CastroS,BrownsonRC,ClausJ,OrleansCT. Acceleratingevidencereviewsandbroadeningevidence standardstoidentifyeffective,promising,andemerging policyandenvironmentalstrategiesforpreventionof childhoodobesity.AnnuRevPublicHealth.2011;32:199–223. 21.CapacciS,MazzocchiM,ShankarB,MaciasJB,VerbekeW,

Pérez-CuetoFJ,etal.Policiestopromotehealthyeatingin Europe:astructuredreviewofpoliciesandtheir

effectiveness.NutrRev.2012;70:188–200.

22.DreisingerML,BolandEM,FillerCD,BakerEA,HesselAS, BrownsonRC.Contextualfactorsinfluencingreadinessfor disseminationofobesitypreventionprogramsandpolicies. HealthEducRes.2012;27:292–306.

23.FarleyTA,VanWyeG.Reversingtheobesityepidemic:the importanceofpolicyandpolicyresearch.AmJPrevMed. 2012;43:S93–4.

24.McPhersonME,HomerCJ.Policiestosupportobesity

preventionforchildren:afocusonofearlychildhoodpolicies. PediatrClinNorthAm.2011;58:1521–41,xii.

25.SendiP,AlMJ,GafniA,BirchS.Portfoliotheoryandthe alternativedecisionruleofcost-effectivenessanalysis: theoreticalandpracticalconsiderations.SocSciMed. 2004;58:1853–5.

26.SendiP,AlMJ,GafniA,BirchS.Optimizingaportfolio ofhealthcareprogramsinthepresenceofuncertainty andconstrainedresources.SocSciMed.2003;57:2207–15. 27.ChanC,DeaveT,GreenhalghT.Childhoodobesityin

transitionzones:ananalysisusingstructurationtheory. SociolHealthIlln.2010;32:711–29.

28.HammondRA.Complexsystemsmodelingforobesity research.PrevChronicDis.2009;6:A97.

29.LukeDA,StamatakisKA.Systemssciencemethodsinpublic health:dynamics,networks,andagents.AnnuRevPublic Health.2012;33:357–76.

30.CairnsG,AngusK,HastingsG,CaraherM.Systematicreviews oftheevidenceonthenature,extentandeffectsoffood marketingtochildren.Aretrospectivesummary.Appetite. 2012.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2012.04.017

31.KraakVI,StoryM,WartellaEA.Governmentandschool progresstopromoteahealthfuldiettoAmericanchildren andadolescents:acomprehensivereviewoftheavailable evidence.AmJPrevMed.2012;42:250–62.

32.FarmerP.Pathologiesofpower:health,humanrights,andthe newwaronthepoor.Berkeley:UniversityofCaliforniaPress; 2003.

33.McKeeM,StucklerD.Theassaultonuniversalism:how todestroythewelfarestate.BMJ.2011;343:d7973. 34.SwartzJJ,BraxtonD,VieraAJ.Caloriemenulabelingon

quick-servicerestaurantmenus:anupdatedsystematic reviewoftheliterature.IntJBehavNutrPhysAct.2011; 8:135.

35.FarleyTA,CaffarelliA,BassettMT,SilverL,FriedenTR.New YorkCity’sfightovercalorielabeling.HealthAff(Millwood). 2009;28:w1098–109.

36.BornB,PurcellM.Avoidingthelocaltrap:scaleandfood systemsinplanningresearch.JPlannEducRes. 2006;26:195–207.

37.WilsonD,RobertsJ.Specialreport:howWashingtonwentsoft onchildhoodobesity.Reuters;2012,April27.Availableat:

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/04/27/us-usa-foodlobby-idUSBRE83Q0ED20120427

38.BrownellKD.Thinkingforward:thequicksandofappeasing thefoodindustry.PLoSMed.2012;9:e1001254http://www. ploscollections.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal. pmed.1001254;jsessionid=415D7371022EF9730DDBC7204F-BAC5AC

39.StiglitzJ.Thepriceofinequality.NewYork:Norton;2012. 40.OrganizationforEconomicDevelopment.Growingunequal?

IncomedistributionandpovertyinOECDcountries.Paris: OECD;2008.

41.BeagleholeR,BonitaR,AlleyneG,HortonR,LiL,LincolnP, etal.UNhigh-levelmeetingonnon-communicablediseases: addressingfourquestions.Lancet.2011;378:449–55.

42.WHORegionalOfficeforEurope.Actionplanfor

implementationoftheEuropeanstrategyfortheprevention andcontrolofnoncommunicablediseases2012–2016. Copenhagen,Denmark:WHOEurope;2012.

43.GimenezEH,ShattuckA.Foodcrises,foodregimesandfood movements:rumblingsofreformortidesoftransformation? JPeasantStud.2011;38:109–44.

44.GottliebR,JoshiA.Foodjustice.Cambridge,MA:MITPress; 2010.

45.GraffSK,KappagodaM,WootenHM,McGowanAK,AsheM. Policiesforhealthiercommunities:historical,legal,and practicalelementsoftheobesitypreventionmovement. AnnuRevPublicHealth.2012;33:307–24.

46.McKeeM,KaranikolosM,BelcherP,StucklerD.Austerity: afailedexperimentonthepeopleofEurope.ClinMed. 2012;12:346–50.

47.HunterDJ.Meetingthepublichealthchallengeintheage ofausterity.JPublicHealth(Oxf).2010;32:309.