Mobility

and

Family

in Transnational

Space

Ediredby

l|if'arzía

Gras

si and

T

atiana

Ferreira

Cambridge

Scholars

Publishing

Mobitity and Family in Transnational Space Ediled by Marzia Grassi and Tatiana Ferrei¡a

This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Pubiishing

Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tlme' NE6 ZPA, UK

TRgI-E,

OF

CONTENTS

List of Tables and Figures IX

British Library Catalogtring in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Acknowledgements x1

Copyright @ 2016 by Marzia Grassi, Tatiana Ferreira and contributors

A-1I rights for this book ¡eserved. No part of this book may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or t¡ansmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanicaì, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without

the prior permission ofthe copyright owner.

List of

Abbreviations...

...xlll

Introduction

.'...1Marzia Grassi

Part

I:

Mobility and

couple relationships ISBN (10): 1-4438-8601-7ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8601-7 1

Transnationalism and Conjugality: The Angola/Portugal Case

Marzia Grassi

Chapter Two

3I

Illegalization and Social Inequality in the Regulation of Marriage

and Migration Control in Portugal

M ar ianna B ac c

i

T amburlini

Chapter Three... 55

Day to Day

Life

of Transnational CouplesTatiana Ferreira

79

Marriage and Migration in Portugal: Exploring Trends and Patterns

of Divorce in Exogamous and Endogamous Couples

Ana Cristina Femeira, Madalena Ramos and Sofiø Gaspar

Part

II:

Kinship

and careChapter Five ...

Transnational Mothers and Development: Experiences of Salvadoran

Migrants in the United States Leisy J. Abrego

VI Table of Contents

Chapter

Six...

...'...ll7

Intergenerational Solidarity in Transnational Space:

The Case of Etderly Parents Left Behind in Lithuania

M ar g ar ita Ge dvíIait è - Ko rdusiené

Chapter

Seven...

...'...141 Parenting from afar: Parental Arrangements AfterMigration-The AngolaÆortugal Case Luena Marinho

chapter

Eight...

... 161Migrations, Vy'omen and Kinship Networks in the Western Indian Ocean:

A

Comparative PerspectiveFrancesca Declich

Part

III:

Gender and generations across bordersChapter

Nine...

...'...'...179Veracruz Migrants Travelling North: Transnationalism from Intemal

and International Migrations in Mexico

Blanca

D.

Vásquez DelgadoChapter

Ten...

..'...'... 199 Courageous Vy'omen Crossing the Eastern Border between Mexicoand the United States Teresa Cuevq-Luna

Chapter

Eleven

....217A

Gender Approach in Brain Drain: The New Labor Precariousnessof Highly Skilled Portuguese Women

Maríø de Lourdes Machado-Taylor, Rui Gomes, João Teixeíra Lopes,

Luísa Cerdeira and Henrique Vaz

Chapter

Twelve

...'...231A

Metaphorical Representation of the Children of Cape VerdeanImmigrants' Transition to Adulthood: An Analysis of the Plot Structure

and Character Constellation in the Feature Film Até Ver a Luz (2013)

Rosemarie Albrecht

Mobility and Family in Transnational Space vll

Chapter

Thirteen..'....

""""""""

251The Individualization of Kinship Ties in a Transnational Context:

Bahian-Capoeira Collectivities and Afro-Venezuelan Religious Groups

Ro ger Canals and Theodora Lefkaditou

Contributors.

""""

271Cuaprnn

Ss,vBN

PRNBNUNG

FROTU

APER:

PNNNXTNT ANNENGEMENTS

Arrpn

MtcneuoN-TuB

ANcola/Ponrucnr

Ces¡'

Lupxe

MaRnqHo'

I

Doctoral candidate inSociologY at the Institute of Social Sciences, University

of

Lisbon, Portuguese Foundation forScience and Technology (FCT-Fundação para

Introduction

Transnational

families are

not

a

new

phenomenon' Research ontransnational

family r,u",

t"r

ledto

a growing bodyof

empirical.studiesil-,*;;*".

cio¡uri"uti* and'iformation

and

CommunicationsTechnology

(fCO

traveîreated

conditions that help families survive thegeographical distance,

t,"Vittg

con1l9led'.This is

focusedmainly

on theimpacts

of'

transnatto;l';;y

of

life

-in

migrant

mothers and, theirinteraction

witt

tttos"

iel

úehin¿,

while

fathering

practices during,iËrãri*

rr"ve received less attention. Despite the efforts made by parentsto

easethe

geograpniJ-t"putution' often there are

changesin

the relationship between parents andchildren'

such asthe

lossof

parentaluliflotity oi

the weakening of emotiona.l bonds'The

aim

of

this

cirap"teris to

analyzehow

the relationship betweenp;;;;

aná ctritdren is ahected by the migratory project' a10 atloi-{;1tiÛ

what practices are carried out by migrant parents to exercise parenting at distance.The

original

data upon which.this-chapter wasbuilt

comefrom

thefieldwork carried

"",

*'oái

the project places and belongings:coniugality

between Angola

,r¿

i,-"inià¿'wtrictr

aimsto

comprehend the effectsof

142 Chapter Seven

mobility on

conjugality andfamily life,

and how the (re)constructingof

"home" is made by the migrant, favoring the male point of view.

Starting

with

a

brief

overview

of

the migratory context

betweenAngola and

Porhrgal,followed

by

a

descriptionof

the

methodologyadopted, this chapter focuses on migrant parents' narratives regarding their parenting practices and the effects of distance in the relationship

with

theirchildren.

In

order to perceive how parenting from a distance is exercisedand

managed,this topic

of

the interviews

soughtto

assesshow

thedecisions regarding

the

childrenwere

organized,the

perceptionof

theimpact of distance on parental authority, the impact of distance on creating conflicts, and the existence ofsupport in caring for children.

The

analysisof

the

interviews revealsthat

transnational parentingpractices are based on communication,

with

ICT having an important rolein

the livesof

migrants andin which

fathers interviewed seemto

sufferemotionally due to the separation from their families.

This article contributes to the study oftransnational parenting practices

and the adaptation

to

the newfamily

roles imposedby

the transnationallife

style, highlighting paternal involvement and questioning the conceptof masculinity.

Migration

between

Angola

and

Portugal

Past and Present

Migrations between

Angola

and Portugal havea

specific character,which

is

groundedon

long-standing relationships betweenthe

twocountries, marked

by

oppression and colonialism. The Porhrguese arrivedin

Angola at the endof

the hfteenth century, and there was a progressiveassimilation that

led Angola

to

the

categoryof

overseas colonyof

thePortuguese Empire. Relations between Portugal and Angola were guided

mainly by trade (slave trade and later,

with

the prohibition of trafhcking,various products such as coffee, sugar cane, sisal,

iron)

and also culturalexchanges, although the condition

ofPortugal

as colonizing country tendsto have a forceful character.

Following the independence of several other African countries, Angola

initiated

a

liberationwar. This war, known

among Portugueseas

thecolonial war,

extendedfrom

1961to

1974. Thefall of

the

Portuguesepolitical regime provided

the

Angolan

independence.Angola

wouldbecome an independent country, recovering its sovereignty on November

ll,

1975.V/ith

the independenceof

the country, acivil

war began that lasted2T years, ending Ln2002. Thecivil

war in Angola was a strugglefor

power between the two main liberation movements Popular Movement

of

Parenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

143Liberation

of

Angola (MPLA-Movimento Popular de Libertação

deAngola-) and National Union

for

the Total

Independenceof

AngolapNITA-União

Nacionalparo

a Independência Total de Angola)of

the country.It

was dividedinto

three periodsof major

combat-1975-1991 ,1992-1994, and 1998-2002, interspersed with periods oftenuous peace.

Angolan migration

to

Portugal beganin the

16th century. Over timethe

flow

experienced periodsof

greater intensity.According

to

Grassi(2010),

in

the 20th

century themain

periodsof

Angolan migration toPortugal were in the 1960s with the amival of a small group of students; in

the

period following

the

fall

of

the

Portuguesedictatorial

regime 0974175), when there was a retumof

Portugueseliving in

Angola and Angolans also. In the 1980s following the repressionof

the political coupof

lhe 27th

May

1977,a

considerable nurnberof

Angolanswent

toPortugal.

Later

in

the

late

1990sand

in

the early 21st

century, theintensif,rcation of the

civil

war in Angola led many Angolans to migrate to Portugal, some to settle, and others to move on to other destinations. Theconnection

to

Portugal,

the

common language

and

some

culturalproximity,

made Portugalthe

chosen destinationfor

many

Angolans seekingto

escapethe

armedconflict

or

looking

for

a

betterlife

and opportunities.Porfuguese migration to Angola begins

in

the 1930s, motivated by thecolonies settlement

policy. According

to

Claudia

Castelo(2007),

thepolicy

developedby

the

Stateto

settlethe

colonieswith

motherland citizens sought to maintain and enforce sovereignty over these tenitories.The author states

that

thepolicy

was developedin

two

stages:a

firstmoment,

initially

plannedby

the State; the second moment,from

1929(global crisis)

until the

SecondWorld

War,in which

migrationdid

notdepend

only on

state intervention,but

alsothe individual initiative

of

many Portuguese who sought better

living

conditions.At

the same time,the

spreadof

the

ideaof

the

colonies asan

extensionof

Portuguesetenitory beyond the sea facilitated the option for migration.

The collapse of the Salazar regime in Portugal and the outbreak of

civil

war

in

Angola

triggeredthe retum

of

many

Portuguesewho were

inAngola.

The

1980s and 1990s, witnesseda

reductionin

the volumeof

Portuguese

emigration.

Portugueseemigration

to

Angola, given

thepolitical situation and the

military

conflictin

the country, virhrally ended.The global financial crisis

of

2008

encouragedits

return

andAfrica

emerged again as a migratory destination, with Angola the top destination. The commitment to rebuilding the country meant that Angola undertook a

large number

of

public

works.This

andthe

economic growth madeit

144 Chapter Seven

combined

with

a precarious and unstable economic situationin

Portugal, ledr'any

Portuguese to migrate to Angola.Today the situation

is

different.

We can

seethat the

number¡¡

Angolan migrants

in

Portugalis

decreasing, dueto

a returnto

the hor¡scountry,

which

currentlyis

economically more appealing than Portugal.The progress

of

the Angolan economy and the economic crisis affectingPortugal

is

encouraging Angolansto

retum

to

their

countryof

origin.Currently

it

appears that the numberof

Porfuguese citizens residing inAngola is greater than the number

of

Angolansliving in

Porfugal.z Therehas been an apparent reversal of the migration flow.

Ferreira and Grassi (2012) also refer to the reversal of migration flows

between Portugal and Angola. The authors analyze the migration of young

Portuguese,

noting

that

the

economic

crisis and

the high

youthunemployment rates urge young people to leave. According to the authors

"W'e can conclude that in total 91,900 Portuguese residents in Angola are

mostly young people of working age".

Nevertheless,

according

to

PortugueseImmigration

and

BordersService (SEF, ,Serviço Estrangeiros e Fronteiras),3 Angolans

still

remainthe 5th largest group

of

foreign residentsin

Portugal, representing 5,r/oof

the foreign

populationin

the country,

andthey

arethe

second largestgroup of African migrants residing in Porhrgal.

Methodology

and

Data Collection

Places

and

Belongings:Conjugality

betweenAngola and

Portugalproject used a mixed methodology, using both quantitative and qualitative methods

of

data collection. For more detailed information regarding themethodology followed, see Grassi in Chapter one of this volume.

The data presented

in this

paper resultfrom

the useof

a

qualitativemulti-sited approach. Nina Glick-Schiller (2003) considers the multi-sited

ethnographic research

to

be

a

good option

for

studying transnationalmigration,

in

particular

transnationalfamily

life.

Data collection

wascarried out

in

two contexts: Angola and Portugal, seeking to gain a better understanding of the impactsof

migration on family members who are indifferent geographical contexts.

The data were collected through semi-structured interuiews.

Regarding the sample, atotal of 27 interviews were conducted: 10 with

Portuguese parents

in Angola,

and 17with

Angolan parentsin

Portugal.2

Consular Data Records, stocks 2008-2014 available in

http ://www. observatorioem i g r acao.ptl np 4 I pai ses. html? id:9.

'

RIFA 201 3 (lmmigration, BorderJ and Asylum report, 201 3)-l

I

Parenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

145Also,

5

interviewswere

madewith

Porfuguese women and used as acontrol grouP'

The interuiews took place

in2013 and2014.In

Angola these were inLtanda, and

in

Portugal were mostlyin

Lisbon, but alsoin

Leiria (some,in

the control group). Regarding the sampling method,for

interviews inthe control group (women with immigrant husbands in Angola) the type

of

sampling used was snowball.

To

make the interviewswith

the migrantsthemselves, a convenience sample was used'

Sample characteri

zation

One

of

the main

focusesof

interestof

the project "Places

and Belongings: Conjugality between Angola andPortugøl" is

transnationalfatherhood,

and the

samplewas colrposed

of

male individuals with

children and who are immigrants.

In

this

sample,migration

of

Angolans

to

Portugal

is

older

thanmigration

of

Portugueseto

Angola. The Angolan interviewedwho

hadbeen

in

Portugal the longestarived in

the countryin

1988. On the otherhand, conceming the Portuguese

in

Angola,it

was foundin

the sample that the earliest migration dates back to 2008, the year coinciding with theworsening

of

the economic crisisin

Portugal. Regarding the reasons forthe migration,

in

the Angolan case these were aboveall

the war and thesearch for better

living

conditions; while the most recent migrants come toPortugal

with an

educationalor

training pulpose.

The

Portuguesemigration to Angola is economically driven, based on the

job

search and the high-salaryjob

offers.In relation to sending remittances to family, all Portuguese respondents

claim to send remittances; some of them say they send their entire salaries home,

living

on incomes of more informal activities. Portuguese migrationto Angola has a markedly economic character. The main reason

for

thismigration

is

the

wages offeredand the

opportunitiesfor

professionalgrowth. Sending remittances somehow

justifies

the choiceof

migration,which allows a better quality of

life

forfamily

membersin

the countryof

origin.

In

contrast, Angolan migrants send fewer remittances-usually notat all.

Most of

the respondents who migratein

orderto

obtain education(most recent migrants) are still receiving their wages in Angola, so they do

not feel the need to send remittances.

Angolan migrants usually have

more

children

than

Portuguese migrants. Angolans have between one and eight children, while Portuguese have one or h¡/o. Angolan migrant parents tend to have older children than146 Chaptel Seven

vary

betweenI

and

38

yearsold, while the

agesof

the

Porhrguesemigrants' children are

between3

and2l

years. Regardingthe

care arrangements, children tend to be cared for by their mothers.With

the father's migration, mothers tendto

gain more responsibilityand decision making power.

Migration

and

Transnational Parenting

Earlier migration studies were especially interested

in

issues related tothe assimilation and labor integration of the migrant in the host country, or

in the

impactof

remittances sentby

migrants. Transnationalism studies appearedin

theearly

1990s,giving

particular attentionto

thelinks

thatmigrants had with their home countries (Levitt 2001;

Grillo

2001; Kivisto2001; Smith and Guarnizo 1998; Vertovec 1999; Glick-Schiller, Basch,

and Szanton-Blanc 1992), opening

a

new perspectiveto the

studies onmigration

that

focusedmainly

on

the

country

of

origin

perspective(especially

on the

impacts

of

migration and

the

effects

of

migrantremittances).

Glick-Schiller Basch, and Szanton-Blanc (1992) consider transnationalism

to be a social process

in

which migrants establish social helds that crossgeographic, cultural, and

political

boundaries.In their

opinion, migrantsdevelop and maintain

multiple

relationships:family,

economic, social,organizational,

religious,

and

political,

maintaining consistent

andcontinuous ties.

However, interest in transnational families and individuals who remain

in

the

countryof

origin

is

more recent.The

literatureon

transnationalfamilies

appearsafter

the year 2000

(Mazzucatoand

Schans, 2008),emerging from the extensive literature on transnationalism. According to

Zontini (2007), transnational families are not new, and are characteristic

of

migrant labor forces of the early twentieth century, when male workers

of

some European countries migrated to the United States and Latin America,

leaving their wives and children behind. The transnational

family

resultsfrom

the migration

of

one

or

more

elements.The main feature of

transnational families according Bryceson and Vuorela (2002) is the fact

that they

have members scatteredin

different nation

states,and

yet maintain a sense of unity and collective well-being. The social componentof such families is also underlined by Herrara-Lima (2001), who considers

that transnational families are leveraged by vast social networks that allow

the

flow of

transnational experience. According to this author, the familymembers who are separated are united in a social space through emotional

and financial ties, keeping in touch through media and occasional physical

Parenting from Afar: Palental Arrangements After

Migration

147ñovement between country

of origin

and the host country. The studyof

tiansnational families has givenrise

to

several .thematic approaches'A

fror" "totto-ic

approach,which

focusesmainly

on the

impact.of

renittances

on

the

householdand

on

the well-being

of

the

families-(Carling

2002;

Guamizo 2003; Schmalzbauer 2004); another approachìhut

fo"ut"t

mainly

on

the

impactof

remittancesin

the

communitiesitcuUki, Mazzucato, and Dietz 2007;

Osili

2004) and the developmentof

ìh" rounrry of origin of the migrants (Ratha 2003; Adams and Page 2005);afld

aî

approachthat

leans more towardthe

analysisof

the

effectsof

migration -Migration on its Protagonists.

affects parenting

by

introducing changesto

its practices.It

pay

sometimes lead to a weakening of parental position sinceit

introducesa discontinuity

in

the performanceof

parenting. Migration has an impacton how parents exercise their parenting and affects the relationship

with

the children. The distance and the lack of dailylife

complicity require the creation of new family dynamics and alternative ways to monitor, cherish,and to discipline children, and this tends to

differ

according to the genderofthe Parent.

Usually the

family

member who migrates is the father, but given thedemand for labor,

in

areas such as care and domestic workers, the numberof

women migrating has grown

exponentially. Transnational familystudies have largely focused on impacts of migration on migrant mothers,

especially regarding

the

emotional distress,thereby

disregarding theimpacts on the well-being of fathers'

There

is

an extensive literature on transnational motherhood (Segura1 994 ; Hondagneu- S otelo | 9 9

4;

Alicea 1 997 ; Hondagneu- S otelo andAvila

1997; Parreias 2001, 2005; Aranda 2003; Waters

2002;

Schmalzbauer2004;Panado and Flippen 2005; Nicholson 2006; Falicov 2007; Gamburd 2008; Hewett 2009; Wilding and Baldassar 2009; Zonlini 2004; Boccagni

2012; Carling, Menjívar, and Schmalzbauet 2012;

Millman

2013). Thisliterature focuses on issues like the financial support. Studies point out that

mothers tend

to

remit more, perfotm more frequent communication, and exercise an affective monitoring that increments participationin

the lives of children, helping to minimize feelings of guilt. The studies focus on thegeographical areas of Asia (Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, etc.), Latin

America (particularly Mexico), the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe.

The literature

on

transnational fatherhoodis

less extensive andis

amore recent research area (Pribilsky 2004,2012; Dreby 2006; Bustamante

and Alemán 2007; Avtla 2008; Paneñas 2008; 'Waters 2010; Nobles 2011;

Leifsen and Tymczuk 2012;Harper and Martin 2012; Kilkey, Plomien and

7

t48 Chapter Seven

exercise

of

parenthoodat

a

distance, exposingdifferent

strategiess¡

proximity and strengthening emotionar ties ãnd cãre deveroped by

irigrant

men who

seekto

maintain

a

presencewithin the famiìy

oãspite- trregrcographical separation.

It

is

worlh

mentioningthe

work

or

lìibltsty

(2004)

on

Ecuadorian migrantsin

New

york

ãndhow they carry

outreconfiguration

of

marital relationships,family

life from

a distance, andgender roles within the family; the study

of

waters (2010) on migrantsof

Asian origin in canada and the challenges of becomingpri-ury

cãregiversof their

children when their wives returnto

Asia; the studyof

paúeñas(2008)

that

analyzed the transnational paternalFilipino

parents, findingthat

parental practices comeinto

line

with

the

trãditional patternsof

gender (the father is the breadwinner and his function has to do more with

discipline and imposing order and authority over children, than providing

emotional support

for

children

or

establishing

a

close

affective relationship); and also thework of

Nobles (2011), who analyzed familiesin

which there was no parental co-residence (due to migration or divorce)and found that

if

the relationship between parent andillit¿

Ir

close, themigration

hasa positive effect

on

incentivefor

activities and sciool

performance.

Transnational Parenting

and

Communication

Scholars

working on

parentingand

careat

distance consider thatmaintaining intimate relationships

in

transnationalfamilies

depends onseveral care practices that involve the circulation

of

objects, vaìues, and persons' and also on communication. According to parreñas (2001,l2l),

in

transnational families the lackof daily

interaction prevents ramitiarityand

becomesan

irreparable

gap

in

the

denìnitiónof

parent-childrelalionships.

The

lÌequencyof

contactis

very

importantio

maintainsocial bonds.

New information and communication technologies have brought more

ways

to

communicate, more accessible, more varied. The useoi

mobilephones offers new opportunities for

mobility

in time and space and socialintegration

in

everyday

life,

offering

the

possibility

ìf

direct

andimmediate interaction. The voice can convey ihe reetings and emotions.

This

technologyis

extremelyuseful

in

the

caseof

migrants, sinceit

facilitates their participation and allows them

to

keepup with

the dailyroutines

of

their

families. People can keepa

senseof

community andcontinue

to

function asfamilies.

oiarzabal and Reips (2012) emphasizethe role

of

ICT

as

helpersto

construct transnaiionaland

dàsporiccommunities.

Parenting from Afar': Parental Arrangements After

Migration

749Communication between couples, particularly those who are dispersed

in

the

transnational spaceis

very

important. . Communication createsproximity and allows

the

sharing

of

information and feelings,

andfacilitates

the

maintenanceof

social ties. The transnationalway

of

liferequires

a

reconfiguration

of

the

fonns

of

social

interaction.Cornmunication through various media plays a key role for those who are

unable

to

make faceto

face interactions. Communicationin

migrationcases helps minimize the effects of what Falicov termed uprooting (which

according

to

the

author can

be

of

three types: social, cultural,

andphysical).

In our sample we notice that more recent migrants have the propensity

to

communicate

more

with

their

children/family,

often

daily. Communication between the Poftuguese migrant parents and their childrenis less spaced than communication among Angolan migrant parents and

their children. For more details regarding the communication practices

of

the sample see Chapter one.

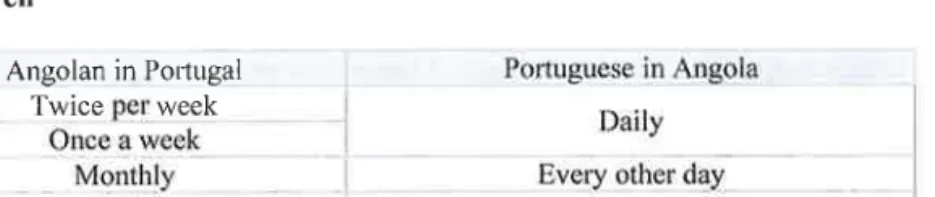

Table 7.1

-

Frequencyof

contacts betweenmigrant

parents andtheir

children Angolan in Portugal Twice week Once a week Monthly Sporadically Daily

Source: Grassi (2015) Research project"Places and belongings: Conjugality

between Angola and Portugal" (PTDC/AFR/1

l9l

49 12010), ICS-UlisboaParents

that have older children and that have

a

longer time

of

migration tend to have a different frequency ofcontacts."I

neve[ had cornrnunication routines perhaps because ofhaving been herewhen there was no possibility

of

having routines...we speak, we speakregularly, we talk when we have to talk, I can speak three or four times a

day, I can, not speak fo¡ two or three days, I don't have a tight routine"

(Porluguese man living in Angola)

In terms of means used to communicate, we verified

in

our sample thetrend

for

Portuguesemigrant parents

to

use more

skype,

whilecommunication

of

Angolan migrant parents

with

their

children

ispreferentially over the phone:

Portuguese in Angola

Daily Every other day

Whenever can

1s0 Chapter Seven

"it's always mobile phone, only by phone. She doesn't have internet there (...) we speak once a week for about one hour"

(Angolan man living in Portugal)

Apparently the Portuguese migrant parents use

a

greatervariety of

means of communication.

Table 7.2

-

Means used to communicatewith

thefamily

Angolan in Portugal Telephone Potluguese in Angola Skype Facebook Viber Text messages E-mail Viber

Source: Grassi (2015) Research project"Places and belongings: Conjugality

between Angola and Portugal" (PTDC/AFR/1 1914912010),ICS-ULisboa

Portuguese migrants prefer

to

use Skype becauseit

allows viewing,thereby minimizing the distance, creating a sense of closeness through the

"virtual

presence."It

is seen as a tool and an ally in the distance parenting,which

helpsto

easethe

distance. Oneof

the respondents describes theimpacts of using Skype as the sense of being close.

"If

I had not seen him for, maybe, 3 or 4 months, maybe I could not standthe way I stand, right? As I see it every day, I know he is well, know when

he...

uh, until he... sometimes on weekends he goes fishing...I

know when he picks up a sunburn...I mean we ended up being close.',(Portuguese wife, partner in Angola)

Sþpe

is used as a meansfor

maintaining the presence, continuing toexercise parental authority, and performing tasks

that

before migrationwere made

in

person, such asplaying with

thechild,

studying, helpingwith

the homework; and alsoto

draw attention to the behavior.It

allowsthe migrant parent to accompany the everyday

life

of their children: ,.whenthe youngest lost a tooth she showed me on Skype, so happy!" (portuguese

man

living in

Angola). Oiarzabal and Reips (2012) emphasize the roleof

ICT as helping to construct transnational and diasporic communities.

The following quotations are examples of the activities carried out via

Skype by parents and their children:

"Even games...like the hanged man we got to play on Skype (...)

I

found that my youngest was already reading and joining words together',(Portuguese man living in Angola)

Parenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

151"I do homework with my kids at night on Skype whenever I can' The other

day, I was studying up to 10:30 prn, 11 prn with D, math there on Skype,

we had to review all his lessons...we were there studying for about four hours"

(Portuguese rnan living in Angola)

"lt

has happened for exarnple G is doing homework and he is doing thework with him by Skype"

(Portuguese wife, partner in Angola)

Bacigalupe and Lambe (2011) consider ICT

"anew

family member" in transnational families, a sourceof

social capital, which promotes speecheand helps create

a

sense thatthe

loved ones are present.All

this

mayinclude

the

exchangeof

messages betweenmobile

phones, creating asense ofconstant presence and transnational care.

Even though

new

technologiesbring

many advantages and providegreater

proximity,

or

the

maintenanceof

transnational social networkslWitAing 2006),

to

some individuals

it

is

not

enough.One

of

thePortuguese interviewees saYs :

"Today we have Skype, we have the Messenger, we have the phone, that's

all

very pretty, butit

doesn't work, because you being on a computer screen is not the same as being there '.. You are not present there' and those daily hours, you create the habit ofbeing here one hour, but an hour on the computer the kids are distracted seeing caftoons, she's distracted because she has to go make dinner for the kids (...) and if you are at home you are there, present, and really being here even being ableto

usetechnologies to bring you closer, I think it does not help much, it is good to relieve the longing, but no"

(Portuguese man living in Angola)

Effects

of the Distance

Distance affects parents and children,

modi$ing

the existing familydynamics.

In

the sample parents repodat

an earlier stageof

migrationfèelings

of

loneliness, depression, andlack

of

emotional contactwith

family

and friends.In

relationto their

children, the distance sometimesmakes

them feel

powerless,by

not being

presentthey

are unable toquickly help or cherish their children.

Sadness and longing were also mentioned by the migrant parents'

"Only once

I

felt it...my

youngest-

even the teacher spoke with herParenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

153 In the above quotationof

a Portuguese father,it

is possibleto

realize thathe

is

very

awareof

the

consequences, becausehe

has

alreadyexperienced a similar situation personally.

"l

got to the conclusion that rny daughter was creating a set ofhabits.thatare... these habits that

I

think were influenced by my distance,in

the distance between us, in the fact that I have been here as long as I've been"(Angolan man living in Poltugal)

Parents also mention modifications regarding

the

parental authoritythat is diminished by the distance. They reinforce the importance of being

present.

"Q: Do you think that the distance interferes with your authority with your

daughters?

A: Until now no, but at some point it will start to happen ..' because at this

stage they ...The authority ofthe ten years, is different from the authority offourteen, fifteen".

(Portuguese man living in Angola)

"Being present is very impottant. When it is missing you lose the authority,

is it not?"

(Angolan man living in Portugal)

rhis

chapterr",

.":,:l::iilffiïÏ,,

"*"..,,"

orparenting at distance.My

analysis based on the Angola/Portugal case shows that themain effects reported by the migrant parents regarding the distance in their

parental relationship were emotional detachment, the loss

in

the decision-making, the loss of parental authority, and the lackof

sharing of the dailylife-lack

of sharing of the small and the big moments of the child.Transnational

parenting

practicesare

basedon

communication-parenting

by

Skype, especiallyin

the Portuguese case and more recentAngolan case. For most Angolan migrants residing

in

Porhrgal, parenting is done by phone; the parenting practices also include making visits to the home country or visits of the family to the host country. In this sample anapparent

tendency

exists

for

the

Portugueseto

carry

out

morecommunications with the children and also to carry out a larger number

of

visits

to

the countryof

origin. Portuguese migrantsin

Angola are betterpositioned

in

the labor

marketthan most

of

the Angolan

migrants inPortugal, and tend

to

have qualihed and better paidjobs.

The economic class also influences theway

migrants communicatewith

their families.152 Chapter Seven

and she said she was sad; she was sad because she rnissed me.

I

was stunned, with my heart pouring blood."(Portuguese man living in Angola) "When you are present it works another way, and when you're absent they think everything is also absent, so things do not go as it should be"

(Angolan man living in Portugal)

Regarding the effects

of

the distance on children, the distancein

theparental relationship has effects on

children-the

distanceof

the parentsaffects the emotional well-being

of

children. Several parents repoft somechanges

in

their

children's behavior.In

the following

quotesfrom

theinterviews,

parents describesome

of

those effects as difficulties

inconcentration and psycho-somatic disorders.

"He is a troubled kid, he's a kid that gets distracted very easily and also by the fact that I'm here, the kid...the kid has more need of attention"

(Portuguese man living in Angola)

"My

son went through a phase...and this has to do with the emotional paft...also by the fact that the father is not here...uh, every day his head ached... migraines, every day his head ached, then disappeared"(Portuguese wife, paftner in Angola) Parents tend

to

consider that the distance brings differencesinto

therelationships---rreates emotional distance leading

to

lack

of

emotionalproximity. One

of

the

interviews

mentioned regardingthe

parentalrelationship between father and daughter:

"the close relationship he had with his daughter ... he always loved her, and

it

seems that all this was fading,it

was creating a remoteness and..., andthis gap has been, it has been made effective."

(Portuguese wife, paftner in Angola)

Parents seem

to

be

awarethat

distance influencesthe

relationshipbefween them and the children.

"What

I

lose, effectively lose the sharing of space, emotions, everything else, lose the pleasure of being with my children...That is a bill that Iwill

pay later is it not ...And I'm aware of it, because my dad is paying it with

mgt'

154 Chapter Seven

For

instance, mostof

the Angolansdo not

useSþpe

because familiesback home have

no

computer, Internet,or

the know-howto

useit.

Theculture

of

family organization also seems to haveeffects-Angolans

haveextended

families that

endup

being more

supportive and protective;Portuguese tend

to

have nuclear families,which

havea lower

supportnetwork, creating

a

greater needfor

migrantsto

monitor and support thefamily.

ICT

assume great importance in the lives of most migrant parents, and are the way to stay in contact with their families.For

some migrant parents thereis a

coolingin

the relationship withtheir children (i.e., an emotional detachment of children).

In

order to mitigate the distance they feel from their families, and ease the emotional wounds causedby

their migratory project, migrant parentstend to focus on migration objectives

in

order to endure the distance-theyreinforce

their

breadwinnerrole giving

enhanced importance (especiallyby sending remittances), parlicularly in the case of Portuguese men whose

migration to Angola assumes an economic character; or the importance

of

getting an education in the case of the Angolan man.

References

Adams, Richard and John Page. 2005.

"Do

international migration andremittances

reduce

poverty

in

developing countries?"

WorldD eve lopment 33 ( 1 0) : 1 645-69. Doi : 1 0. I 5 9 6 / 1813 -9 450 -3 l7 9

Alicea, Marixsa. 1997.

*A

chambered nautilus": the contradictory natureof

Puerto

Rican women's

role

in

the

social

constructionof

atransnational community." Gender and Society ll:.597 -626.

Doi:

10. 1 177 /08912439701 1005005Aranda, Elizabeth. 2003. "Global care work and gendered constraints: The case of Puerto Rican transmigrants." Gender

&

Societyll:609-26.

Doi:

1 0.1 171 /0891243203253573Avila,

Ernestine.2008. "Transnational

motherhoodand

fatherhood: gendered challenges and coping." PhD diss., Universityof

SouthernCalifomia.

Bacigalupe, Gonzalo

and

SusanLambe.2011. "Virtualizing

Intimacy:Information Communication Technologies and Transnational Families

in Therapy." Family Process 50:12-26. Doi: 1 0. 1

lll

li.1545-5300.20 I 0.0 I 343.xBoccagni, Paolo.2012. "Practising Motherhood at a Distance: Retention

and Loss in Ecuadorian Transnational Families." Journal of Ethnic and

Migr at ion S tu d i e s 3 8 (2) :26 I -7 7. Doi : 1 0. 1 0 8 0 / | 3 69 I 83X.20 12.646 42 1 .

I

Parenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

155Bustamante,

Juan

and

Carlos Alemán.

2001.

"Perpetuating

Split-household

Farnilies-The

Case

of

Mexican

Sojoumersin

Mid-Michigan

andtheir

Transnational Fatherhood Practices."Journal

of

Ethnic and Migration Studies 30:609-29.

Bryceson, Deborah, and

Ulla

Vr.rorela. 2002. The Transnational Family:New European Frontiers and Global Networks. Oxford: Berg.

Carling, Jørgen. 2002.

"Migration in

the ageof

involuntary immobility:Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences."

Journal

of

Ethnic and Migration Studies

28(1):542.

-.

E 2008. c o n o m"The

ic P o I determinants icy 24(3) : 5 82-99.of

migrant remittances." Oxford doi : 1 0. I 09 3 I oxr ep / gm022 Reviewof

Carling, Jørgen, Cecilia Menjívar and Leah Schmalzbauet. 2012. "Central

Themes

in

the Studyof

Transnational Parenthood." Journal of Ethnicand Migration Studies 38(2):19 I -217 .

Doi: I 0. 1 080/13 69 183X.2012.646417 .

Castelo, Cláudia. 2007. Passagens para africa. O povoamento de Angola e

Moçambique

com

naturaís

da

metrópole (1920-1974).

Porto:Afrontamento.

Dreby,

Joanna.2006. "Honor and Virtue: Mexican

Parentingin

theTransnational Context." Gender

&

Society20(l):32-59.

Doi:

1 0.1 177 10891243205282660.Falicov, Celia. 2007 . "Working with transnational immigrants: Expanding

meanings

of

family,

community and culture." Family

Processes46:157-71.

Ferreira, Tatiana andMarzia Grassi. 2012. "Para onde migram os jovens?

Dinâmicas emergentes em Porhrgal." Lisbon: Observatório Permanente da Juventude.

http ://www.opj. ics.ul.ptlindex.php/novembro -20 12

Gamburd, Michele.

2008.

"Milk

Teeth and Jet Planes:Kin

Relations inFamilies

of

Sri

Lanka's Transnational Domestic Servants."City &

Society 20( I ):5-3 1 .

Doi:

I 0. 1 | 1 Ili.l

548-7 44X.2008.00003.x.Glick-Schiller, Nina. 2003. "The Centrality of Ethnography in the Study

of

Transnational

Migration:

Seeing the Wetland Insteadof

the Swamp."In American

Arrivals,

edited by Nancy Foner, 99-128. Santa Fe,NM:

School of American Research.

Glick-Schiller,

Nina, Linda

Basch,and Cristina

Szanton-Blanc. 1992'"Transnationalism:

a

new

analytic framework

for

understandingmigration."

ln

Toward

a

Transnational Perspectiveon

Migration,edited

by Nina Glick-Schiller, Linda

Basch,and Cristina

Palenting from Afar: Parental Arrangements After

Migration

157l(ivisto,

Peter. 2001."Theorizing

transnational irnmigration:A,critical

review of cument efforts." Ethnicity and Racial Studies 24:549-77 .

Doi:1 0. I 080/01419870120049789.

Leifsen, Esben, and Alexander Tymczuk. 2012. "Care

at

distance:Ukrainian and

Ecuadorian Transnational Parenthoodfrom

Spain." Journal of ethnic and migration studies 38(2):219-36.Doi:

1 0. 1 080 I 13 69 183X.2012.646419Levitt, Peggy. 2001. The Transnational Villagers' California: University

of Califomia Press.

ltrlazzvcato,

Valentina,

and

Djamila

Schans.

2008.

"TransnationalFamilies,

Children and the

Migration-DevelopmentNexus."

,SSRCMigration

&

Development Conference Paper No. 20.'oMigration andDevelopment: Future Directions for Research and Policy" 28 February

-

1 March 2008, New York.Millman,

Heather.

2013.

"Mothering

frotn Afar:

Conceptualizing Transnational Motherhood." Totem: The University of Western OntarioJourn al of Anthr op olo gy 2l (1):7 0-82.

Nicholson,

Melanie. 2006.

"Without

Their

Children:

Rethinking Motherhood among TransnationalMigrant

Women'" Social Text 24(3 88): 13-33.Doi:

I 0. 12 1 5 101642412-2006-002.Nobles, Jenna. 2011. "Parenting

from

Abroad:Migration,

NonresidentFather Involvement, and Children's Education

in

Mexico." Journalof

Marriage and Family 73:729-46.

Doi:

I 0. 1 1 I Ilj.l7

41-3737 .2011.00842.xOiarzabal, Pedro and

UlÊDietrich

Reips. 2012."Migration

and Diasporain the Age

of

Information and Communication Technologies."Journalof Ethnic and Migration Studies 38(9):1333-38.

Doi : 1 0. 1 080/ 13 69 183X.2012.69 8202.

Osili,

Una. 2004. "Migrants and Housing

Investments:Theory

andEvidence from Nigeria." Economic Development and Cultural Change

s2@):82r-49.

Parrado,

Emilio

and ChenoaA.

Flippen' 2005' "Migration

and Genderamong Mexican Women." American Sociological Review

70($:606-32. Doi:1 0.1 1 77 1000312240507000404

Parreñas, Rhacel Salazar.2001.

"Mothering from a

distance: emotions,gender,

and

intergenerationalrelations

in

Filipino

transnationalfamilies." Feminist Studies 27 (2): 361 -90.

-.

Gendered Woes. 2005.Children

Califomia:of

Global Migration:

Stanford University Transnational Press.Families

and156 Chapter Seven

Grassi, Marzia. 2010. Forms

of

Familial,

Economic,and

Political

Association in Angola Today: A Foundational Sociolog,t of an African

Slale. New York, London: The Edwin Mellen Press.

-.

Comparative analysis2012. "Migratory

Trajectoriesof

Portugal andfrom Africa, Illegality, and

ltaly."

Workíng Paper0l/2012,

GenderTlNetwork,

ICS-Ulisboa.http://tlnetwork.ics.ul.ptlimages/WP/WP

0l

2012.pdfGuarnizo, Luis Eduardo . 2003. "The Economics of Transnational Living.',

Internationql Migration Review 3l :666-99.

Doi:

10.1lllli.l1

47 -1379.2003.tb00t54.xGrillo,

Ralph. 2001.

TransnationalMigration and Multiculturalism

in Europe. Oxford: Transnational Communities Working PaperWPTC-0l-08.

Harper, Scott, and Alan

M.

Martin. 2012. "Transnational Migratory Labor andFilipino Fathers-How

FamiliesAre

Affected WhenMen

Work Abroad." Journql of Family 34(2):270-90.D oi: 1 0.1 17 1 / 01925 13X124623 64.

Herrera-Lima, Fernando.

200l.

"Transnationalfamilies: institutions of

transnational

social

space."In

New

TransnationalSocial

Spaces:International

Migration and

Transnational Compqniesin

the EarlyTwenty-first Century, edited by L. Pries, 72-92.London, Routledge. D oi: I 0.4324 I 97 80203 4 69392

Hewett, Heather.

2009.

"Mothering across borders: narratives of

immigrant mothers

in

theUnited

States." Women's studíes quarterly31 (3 I 4):121-39.doi: I 0. 1 353/wsq.0.0 1 88

Hondagneu-Sotelo,

Pierrette. 1994. "Gendered transitions:

Mexicanexperiences

of

immigration." Berkeley, California: University of

California Press.

Hondagneu-Sotelo, Pierrette and Ernestine

Avila.

1991.

"'I'm

here, butI'm

there': the meanings of Latina transnational motherhood." Genderand Society

ll:548-7

l.

Doi:

I 0.1 177 /0891243970 1 1 005003Kabki, Mirjam,

Valentina Mazzucato, andTon Dietz.

2008. ,,Migrantinvolvement

in

community development: the case of the rural AshantiRegion-Ghant'.In

Global Mígration and Development, edìted by Tonvan

Naerssen,Ernst

Spaan, and Annelies Zoomers, 150-171. NewYork/London: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

Kilkey,

Majella, Ania Plomien, and Diane Perrons. 2013. "Migrant men'sfathering narratives, practices and projects in national and transnational

spaces:

recent

Polish

male

migrants

to

London."

International1s8 Chapter Seven

-.

2008' "Transnational fathering: gendered conflicts, distant discipriningand_.emotional

gaps." Journal

of

Ethnic

and

Migratíon

Studies

3 4(7 ) : I 0 57 -72. Doi : 1 0. 1 080/ I 3 69 1 È3 08 0223 03 s 6

Pribilsky, Jason. 2004. "'Aprendemos a

convivir':

conjugal rerations,se-parenting, and

family

rife among Ecuadorian transnätlonaln'igiunt.

inNew

York

and the Ecuadorian Andes.,, Global Networks+1:;üì:_:+.

Doi: I 0. 1 I I 1

li.t

47 1 -037 4.2004.00096.x-.

2012. "Consumption Dilemmas: Tracking Masculinity,Money

andTransnational Fatherhood between

the

Ecuadorian Arráesuni

N"*

York Cify."

lourn.a!^o!llhnic

andMigration

Studies SAç4:323_Z+2.Doi: 1 0. 1 080/ 13 69 183X.2012.646429

Ratha,

Dilip'

2003. "Workers' remittances: An important and stable sourceof

extemal development finance."rn

Gtobai Deveropmenî F¡oì,unrn,157-15. V/ashington D.C.: The World Bank.

Schmalzbauer,

Leah.

200_4. ,,searchingfor

wages and mothering fromAfar:

The

caseof

Honduran

transnational families.,,Jouinat of

Marriøge ønd Fømily 66(5):13 17 -33.

Doi: 1 0. 1 1 1 I /j.0022-2445.2004.0009 5.x

segura, Denise. 1994.

"working at

motherhood: chicana andMexica'

Immigrant mothers

and

employment.,,In

Mothering:

Ideotogy,experience, and agency, edited

by

E.N.

Glenn,G.

Chang, andL.

R.Forcey, 211-33. New

york:

Routledge.Smith, Michael

P.,

and

Luis

Eduardo Guamizo,

eds.

199g.Transnationalism rom berow. New Brunswick: Transacíion pubrishers.

vertovec.

1999."conceiving

and researching transnationalism.,, Ethnicand Raciøl s tud ies 22(2) :447 -62. D oi: r 0. I 080/0

l 4 1 98 7 gg32g 5 58

'waters,

Johanna. 2002.

"Flexible

families? ,,Astronaut,, households andthe

experiencesof

lone

mothersin

vancouver,British

corumbia.,, Social qnd Cultural Geography

3:lli,_34.

Doi:

1 0. 1 080 / 1 46493 60220133907-'?019,..

"Becominga

Fatrrer,Missing a

wife:

chinese TransnationarFamilies and

the Male

Experienceof

Lone

parentingin

canada.,,-_

Populatíon, Space andplqce t6:63_74.Doi:

10.1002Zpsf.SZSwilding,

Raelene. 2006."'vi'tua|

intimacies? Families óommunicationacross transnational contexts." Global Networks 6(2):125 _42.

Doi:

I 0. 1 1 1 1 lj.147 t-037 4,2006.00137 .xwilding,

Raelene andLoretta

Bardassar. 2009. "Transnationalfamiry-work

balance: Experiencesof

Australian migrants caringfor

"À"irg

parents and young chirdren across distance and borders.i

louríar

if

Family Studies, Special Issue l5:177-g7.

Doi:

10.5172/jfs.15.2.17;Palenting from Afar: Parental Arrangernents After

Migration

159Zontiní, Elisabetta. 2004.

"Inmigrant

womenin

Barcelona: Coping withtlre

consequencesof

transnationallives." Journal

of

Ethnic

andMigration Studies 30(6):1 113-44.