w w w . e l s e v i e r . p t / r p s p

Original

article

The

planning

system

and

fast

food

outlets

in

London:

lessons

for

health

promotion

practice

Martin

Caraher

a,∗,

Eileen

O’Keefe

b,

Sue

Lloyd

a,

Tim

Madelin

c aCityUniversityLondon,London,UnitedKingdombLondonMetropolitanUniversityandUniversityCollegeLondon,London,UnitedKingdom cNHSTowerHamlets,London,UnitedKingdom

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received18September2012 Accepted21January2013 Availableonline29June2013

Keywords: Planning Fastfood Localenvironments Healthpromotion Localinvolvement Publichealth

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Thisarticleconsidershowhealthpromotioncanuseplanningasatooltoenhancehealthy eatingchoices.Itdrawsonresearchinrelationtotheavailabilityandconcentrationoffast foodoutletsinaLondonborough.Currentpublichealthpolicyisconfiningplanningto localsettingswithinanarrowframeworkdrawingondiscoursesfromsocialpsychology andlibertarianeconomics.Policyisfocusingonbehaviourchange,voluntaryagreements anddevolutionofthepublichealthfunctiontolocalauthorities.Suchaframeworkpresents barrierstoeffectiveequity-basedhealthpromotion.Asocialdeterminant-basedhealth pro-motionstrategywouldbeconsistentwithanationalregulatoryinfrastructuresupporting planning.

©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.Allrights reserved.

O

sistema

de

planeamento

dos

“outlets”

de

“fast

food”

em

Londres:

lic¸ões

para

a

prática

da

promoc¸ão

da

saúde

Palavras-chave: Planeamento “Fastfood” Ambienteslocais Promoc¸ãodasaúde Participac¸ãolocal Saúdepública

r

e

s

u

m

o

Esteoartigoabordaomodocomoapromoc¸ãodasaúdepodeusaroplaneamentocomo umaferramentaparasecomerdemodomaissaudável.Apesquisacentra-sena disponi-bilidadeenaconcentrac¸ãode“outlets”de“fastfood”emLondres.Apolíticapúblicade saúdelimitaoplaneamentoàsestruturaslocais,dentrodeumdesenhoteóricoestreitoque vaidesdeapsicologiasocialàeconomialiberal.Apolíticaestácentradanamudanc¸ado comportamento,nosacordosvoluntáriosenadevoluc¸ãodafunc¸ãosaúdepúblicaàs autori-dadeslocais.Talestruturaapresentabarreirasaumaeficazpromoc¸ãodasaúdebaseada naequidade.Umaestratégiaapoiadanosdeterminantessociaisseriaconsistentecomum planeamentodeapoioàinfraestruturareguladoranacional.

©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublicadoporElsevierEspaña,S.L.Todosos direitosreservados.

∗ Correspondingauthor.

E-mailaddress:m.caraher@city.ac.uk(M.Caraher).

0870-9025/$–seefrontmatter©2012EscolaNacionaldeSaúdePública.PublishedbyElsevierEspaña,S.L.Allrightsreserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsp.2013.01.001

Introduction

and

background

Thereisanextensivepublichealthliteratureoutlining prob-lemsofaccesstoaffordablehealthyfoodsformany,especially low-income, households in England. The development of whathasbeen calledthe obesogenicenvironment, favours theunhealthychoice.1,2Itrequiresmulti-disciplinary

under-standingtomakesenseofcomplexityofthesystemandthus todesignand implementeffective policyacross these lev-els.Problemsoftheobesogenicenvironmentareamenableto beingaddressedbypublichealthandplanninglaw.3–5

Publichealthhasalongtraditionofusingplanningasa toolforchange,6yetinrecenttimesthishasbeenneglected

echoingtheclaimofRiddeandCloos7thatthelinkbetween

healthpromotionandpoliticalsciencehasbeenlost;andthat whilehealthpromotionisessentiallyapoliticalactwishingto addressinequalitiesitfailstousesocialsciencetounderstand theworldthatitseekstochange.Muchliteratureonaccess tohealthyfoodhighlightsthe‘ubiquitous’natureoffastfood outletsinlocalenvironmentsandtheproblematicnutritional statusofthefoodservedfromthem.Few,however,dealwith theplanningsystemasameansofaddressingtheissue,opting fordescriptionoftheproblemandoftenlocatingsolutionsin changingmenuplanningandindividualbehaviourchoice.8

Callsforregulation,oftenelicitcriesof‘thenannystate’. Inlightofthisresponseitisimportanttoemphasisetheuse ofplanningasameansofinvolvinglocalpeopleinshaping theirlocalfoodenvironmentaswellasitsfunctioninpursuit ofhealthyoutcomes.Notwithstandingwideconsensuswithin the publichealthcommunity inunderstanding theobesity epidemiccurrent governmentpolicyinEnglandfocuseson voluntaryundertakings9bytheprivatesectorfoodindustryto improvetheirproducts,andinterventionsinformedbysocial psychologyandbehaviouraleconomicstoprovideincentives forcommunities,familiesandindividualstoadopthealthier behaviour.10

Concernsabouttheunregulatednatureoffastfoodoutlets intheUKhaveledtoacallattheUnitedKingdomPublicHealth AssociationAnnualForum2009from‘TheFood&Nutrition specialinterestgroup’thattheywouldworkto“embedin plan-ningprocessestheabilityoflocalcommunitiestogrow,sellandbuy locallyproducedfood.Localauthoritiesshouldusetheirrestrictive powers (by-laws)to createtheseopportunities byrestrictingfast foodoutletsandsupermarkets”.Giventhefocusonhealth pro-motionthereisaneedtoaddressissuesoflocalpowerand howthiscanbeincorporatedinto anyinitiativethatmight belabelled“paternalistic”indirectingpeopletowardscertain typesofbehaviours.

Health promotion inrespect ofsuch acomplex system must ensure that the focus goes beyond an emphasis on behaviourtoonewhichhelpscreatesupportiveand health enhancingenvironments.TheOttawaCharterforHealth Pro-motionsaysthat‘Healthpromotionistheprocessofenablingpeople toincreasecontrolover,andtoimprovetheirhealth’11,12;our

con-tentionisthatthiscanbedonebyinvolvingplanners,public healthprofessionals and the public indecisions about the localfoodenvironmentbackedupbyregulatorymandatesat supra-locallevelsThisisconsistentwiththerobustupdate ofthe OttawaCharterapproachfoundinthe WorldHealth

Organization’sevidence-richCommissionontheSocial Deter-minantsofHealthwhichcalledforastrategyto:

“Reinforcetheprimaryroleofthestateintheregulation ofgoodswithamajorimpactonhealthsuchastobacco, alcohol,andfood.”13

This articleconsiders the position ofplanning withina healthpromotionstrategytakingtheobesogenicenvironment seriously. A case study approach is used and it draws on researchonfastfoodoutlets(FFOs)inTowerHamlets,a Lon-donBorough.Thecontextforthiscasestudyisthatinthe UnitedKingdomatatimewhenmanyhighstreetretailshops are facingclosure, onearea ofgrowth isthe fastfood sec-tor.Thepredictionsarethatlow-incomegroupswilleatout morefromfastfoodoutletsseekinga‘bargain’,andthereis anopportunityformorebusinessbyattractingmiddle-income priceconsciouslunchtimeconsumers.14

Existing

research

on

fast

food

and

local

environments

Links have been drawn between obesity and fast-food by researcherssuchasPopkin.15Linksincludethecomposition

offoodanddrink butalsoissuessuchaschoice,price and portion size.16Somestudies havefoundaconcentrationof

FFOs in deprived areas and an area effect on food choice andconsumption.17–20Areportonhighstreettake-awaysin

Englandshowedthatfoodfromsuchoutletswasoftenhighin fat,salt,andsugarmakinghealthychoiceshard,evenforthose wishingtomakehealthychoices.21Forexample,aKFCmeal

ofa‘towerburger’,regularBBQbeans,yoghourtandcola pro-vided97percentoftheguidelinedailyamountofsaltand69 percentofsugar.21A2009consumergroupreporthighlighted

similarfindingswithaquarterofchildrenreportingeatingat afastoutletinthelastweekandconsumingtoomuchfat,salt andsugarandoptingforadultsizedportions.22

Withoutaccesstoshopsofferingawidevarietyof afford-able,healthyandculturallyacceptablefood,poorandminority communitiesmaynothaveequitableaccesstothevarietyof healthyfoodchoicesavailabletonon-minorityandwealthy communities.23,24 Members of low-income households are

morelikelytohavepatternsoffoodandnutrientintakethat contributetopoorhealthoutcomes.25Nationaldatafromthe

low-incomedietandnutritionsurveyfoundthatlow-income familiesaremorelikelytoconsumehighfatprocessedmeals or fast-foods and snackfoods.26 The aboveapplies alsoto

childrenandyoungeradultswhospendalargeproportionof theirpocketmoneyonfood.In2005childrenreported spend-ing £1.01 onthe way toschool and 74pon the wayhome largely on the 3Cs ofconfectionary, chocolate and carbon-ateddrinks.27Thisequatesto£549millionperannum.Meals

andsnackseatenoutsidethehomeaccountforabout40per centofcalories.28Fast-foodshaveanextremelyhighenergy

densityandhumanshaveaweakinnateabilitytorecognise foodswithahighenergydensityandtoappropriately regu-late theamount offood eateninordertomaintainenergy balance.Thisproduceswhathasbeentermed‘passive over-consumption’.29Akeypointabouteatingfoodfromfast-food

outletsisthatyoudonothavecontroloverthecontentofsuch food.

Theresearchfindingsonthe locationandconcentration offastfoodand retailoutletsdiffersfrom areatoareaand dependsonthetypeofoutletandqualityandrangeoffood on sale.30 Alarge number and concentrations offast food

outletscanblightanareainseveralways.Forexample, objec-tionstoconcentrationsoffastfoodoutletscanbeasmuchto dowithcrimeanddisorderashealthandnutrition.Location inanareacanoftenbemoretodowithpassingtrade,land prices,parkingfacilitiesandtravelroutesthanwithserving thelocalcommunity31.WorkinLondonshowsthatthe

sit-uationdiffersfromareatoareaandhighlightstheneedfor localassessmentandlocalpracticeinformedbyevidenceand localcircumstances.32Nevertheless,themostrecentevidence

indicatesthatthegeographicaldistributionoffastfoodoutlets varieswithdegreesofdeprivation.33

Researchinthe UK showsthat fastfood outletscan be foundclusteredaroundschools,34,35butlittleworkhasbeen

carriedoutonthesolutionstothisproblemorhowto pre-ventit.Thehighenergydensityoffast-food,andtheimpact onburdenofdiseaseassociatedwiththis,wasemphasisedin theForesightReportTacklingObesities.1Amorerecentreport onfastfoodreportedthatin‘policytermsthesectorisnearly invisible–takenforgranted,yetundertheradarofofficialappraisal andpublicdebate.’(p.3).36Theofficialresponsetothe

situa-tionhaslargelybeenoneducation,informationandlabelling. Alloftheserepresentdown-streamresponsesandstilllocate activityintherealmoftheindividualorfamily.Theseareof coursenecessaryactivitiesandpartoftheoverall approach buttheyareinsufficienttoaddresstheubiquitousnatureof suchoutletsonthehighstreetornearpeople’shomes.This picturepresentsreasonsforconsideringtheuseofthe plan-ningsystemasacomponentofhealthpromotion.

Case

study

of

the

fast

food

landscape

in

tower

hamlets

Below is presented in some detail a case study from one Londonborough,Tower Hamlets,whichhasdevelopedand introduced its own supplemental or extra guidance.37–39 A

casestudyapproachhasbeenadopted40topresentfindings

thatofferlessonsforusingtheplanningsystemandwhich allowsquestionstobeaskedabouttheapproachofplanning anditsfitwithpublichealthandhealthpromotionactivities. Inwhatfollows,thecasestudyisbasedonvariousstrandsof workcarriedoutinaLondonLocalAuthority,TowerHamlets. Thecasestudy:

• provides an overview of the fast food landscape in the authority;

• outlines how evidence-based policy was developed in the authority with stakeholders to address problems of unhealthytakeaways;

• considershowthatpolicyprovidesspaceforplanningasa componentofhealthpromotionatthelocallevel.

TheTowerHamletsworkalongwiththatintheObesCities reportcomparingobesitypreventionstrategiesinNewYork

andLondon41hasspurredanumberoflocalauthoritiesacross

theUKintotakingaction.Allthedataunlessotherwisestated comesfromtwostudies.37−39,41Thedetailofthemethodology suchasmapping,focus groups,observationalstudies,food sampling andpolicyanalysishavenotbeenpresentedhere butcanbefoundinthereportsandarticlesreferenced.37–39

Backgroundtothestudyarea

TheboroughofTowerHamletsisoneofthe33London Bor-oughswithapopulationestimatedat232,000.42Theborough

hasalonghistoryofmigrationfromtheearly1600sonwards withvariouswavesofFrench,Irish,Afro-Caribbeanand,more recently, migrants from the Indian sub-continent settling there,beforemovingontootherareas.43Themajorityofthe

populationarefromanon-whiteBritishbackground,withthe largestminorityethnicgroup(34percent)beingBangladeshi withhalfofthiscommunity‘third’generation–bornlocally. Mortalityratesintheborougharehigh fromheartdisease, and cancers and respiratory disease are highest orsecond highestwhencomparedtootherLondonboroughs.In com-parisonwithEnglandnormsthesearethebiggestcontributors toinequalitiesinlifeexpectancybetweenTowerHamletsand otherEnglishlocalauthorities.44Only15percentofeleven,

thirteen,andfifteenyearoldpupilsintheborougheat5or moreportionsoffruitandvegetablescomparedtothenational figureof23percent.Fifteenpercentoffourtofiveyearold childrenare obese andthis increases to23per cent for11 yearolds;itisthemostdeprivedboroughforincome depriva-tionaffectingchildren.45A2009healthandlifestylesurveyin

TowerHamletsfoundamong16yearoldshighuseoffast-food take-awaysandlowlevelsofconsumptionofrecommended amountsoffruitandvegetables.46Malesreporteating

fast-foodwithafargreaterfrequencythanfemalesandmembers ofethnicminoritygroupssuchasthosefromaSouthAsian backgroundreportinghigherlevelsofeatingout,26.5percent ascomparedto15.4percentfromotherbackgrounds.

Findings

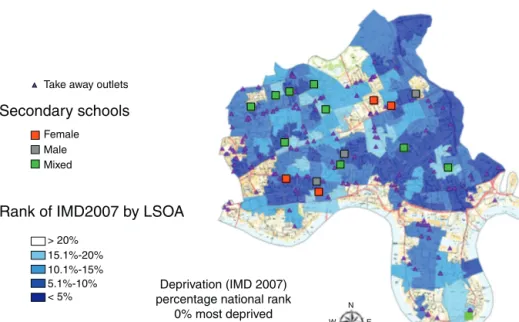

Thereare2214registeredfoodbusinessesintheboroughof which297weregrocersormini-marketsand627wereFFOs. Ninety-eightpercentofhouseholds(93,219)arewithin10min walk of a FFO. At first glance physical access toshops in TowerHamletswouldappeartobeadequatewith76percent of householdswithin10minwalk ofa supermarket,retail market, bakersor greengrocers.Nearly all (97 per cent) of householdswerewithinasimilardistanceofagrocerystore, although ourresearch indicates that many ‘grocery’ stores wouldonlycarryaverylimitedrangeof‘healthy’food.This wasshownbyouruseoftheproxymeasureoftheavailability offivefreshfruitandsevenfreshvegetablesinanyoneshop. Thisshouldbecontrastedwiththefindingfromthemapping that97percentofhouseholdsarewithin10minwalkofaFFO. Similarly98 percent ofschoolshad sixFFOswithin400m and 15within800m(seeFig.1).Samplesofthefoodtaken fromtheoutletsshowedmosttobehighinfat,saltorsugar. Sothechoicespeoplehaveareheavilyweightedinfavourof unhealthyones.

Secondary schools

FFO density

Female Lower N S W E Higher Male MixedFig.1–Densityoffastfoodoutletsaroundsecondaryschools.

TheSchoolFoodTrustin2008publishedfindingsonthe number of junk food outlets around schools in England, devisinganindex ofschoolsto‘junk food outlets’ (includ-ingconfectionaryshops)andrankinglocalauthoritiesonthis basis.47TherewasnoseparatefigureforTowerHamletswhich

wasgroupedwithtenotherLondonBoroughstoprovidean indexof36.7,i.e.37outletspersecondaryschool.Thenational averagewas23outletsperschool,withanurbanaverageof25 outletsper schoolandforLondon 28.Ourestimates ofthe ratiooffoodoutletstosecondaryschoolsforTowerHamlets providesaratioof41.8outletsperschoolwhichcomparesto

SchoolFoodTrustaverageratioof38.6fortheUK10‘worst’ areas.Thedebateover therole thatgeographic accessand availabilityplayindeterminingdietaryoutcomeshasproved contentiousandmuchoftheworkundertakenhasnotbeen onhighlyurbanised,geographicallycompactareas,suchas TowerHamlets.

OurfindingsshowedconcentrationsofFFOsnearschools and in deprivedareas, usingnational deprivation rankings (see Fig. 2),but theseconcentrations didnot persistwhen Tower Hamlets’internalrankingsofdeprivationwere used. TheareaofTowerHamletshassuchwidespreadpovertythat

Take away outlets

Female Male Mixed > 20% 15.1%-20% 10.1%-15% 5.1%-10% N E S W < 5%

Secondary schools

Rank of IMD2007 by LSOA

Deprivation (IMD 2007) percentage national rank

0% most deprived

thedifferenceswithintheareaaremarginalwhereas compar-isonwithneighbouringboroughsshowsuptheseinequalities. Severalissuesemerged.OnewastheclusteringofFFOs;a sec-ondwastheclusteringofFFOsindeprivedareasinthenorthof theborougharoundbothschoolsandneighbourhoods. Samp-lingandanalysisoffoodtypicallyboughtfromFFOsshowed thatitwashighinfat,saturatedfat.

The qualitative and observational study support this contention.37–39Sothereisaneedtoexpandthefocusfrom

hotfast-foodtowhatSinclairandWinkler33callthecold

take-aways,suchasthesandwichshopsandgrocerystores.Our owndatashowthattheavailabilityofthesecoldfoodoutlets ishigh.Alsowhileschoolgatepoliciesrestrictingaccesstothe highstreetwereusefulinpreventingpupilsfrompurchasing foodatlunchtimes,theyhadnoimpactonstoppingpurchase ofunhealthyproductsonthewaytoandfromschool.

TheproblemsarefourfoldforthoselivingintheBorough ofTowerHamlets:

1. Thelackofhealthyoptionsandtheabsenceofanynutrition informationinfast-foodoutlets.

2. Thelackofother affordablehealthy optionsinthe local environment.

3. Largenumbersoftake-awayscontributingtoanobesogenic environmentandlackofhealthychoice.

4. Thelackofownerawarenessoftheproblem,alongwith theperceivedextracoststhatprovidinghealthyfoodwould requireandalackofcustomerdemand.

Researchinformedpolicydevelopment

Findingsfromtheresearchsketchedabovewasusedtohelp informlocalpolicyandactionsintheborough.The presenta-tionofdatawithalocalfocusbroughthometomanyofthe publichealthandcouncilofficialswhatremainsanabstract argumentinreportssuchastheWCRF globalreport.48 The

establishmentofalocaladvisorygroupwasimportantinthis respectasakeyissuewastousethefindingstoinform pro-cessesoftraining support,localhealthpromotionactivities andthedevelopmentoflocalplanningpolicy.Theresearch informationhad to becommunicated in wayswhich were understandableandhadmeaningforawidepolicyaudience. Localdata carriesweight ininfluencing local policy devel-opment. Part ofthe reporting and reviewprocess involved informingthesteeringgroupofdevelopmentsinother geo-graphicalareas.Keyamongthesewasthepotentialtodevelop policyforplanningandregulatingopeningsofnewFFOsin theboroughandforplanningofficialsinthelocalauthorityto workwithpublichealthstaffinthehealthagency.Thishas occurredfollowinganumberofcouncildecisionsand plan-ningappeals.

Thelocal authoritycontinues todevelop this work and has commissioned further research (see http://moderngov. towerhamlets.gov.uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=320&MId= 3416&Ver=4).Thepolicydocumentsresultingfromthiswork havebeensentforpublicconsultation-technicallyknownasa ‘CallforRepresentations’(http://moderngov.towerhamlets.gov. uk/ieListDocuments.aspx?CId=320&MId=3416&Ver=4) and have been approved. The proposalsare for restrictionson

typesofoutletsindesignatedareasoftheboroughsomeof whichare:

• Insomedesignatedareastherewillbenonewopeningsof FFOsduetotheadverseeffectonthequalityoflifeforlocal residents

• FFOs willnotbeallowedtoexceedfiveper cent oftotal shoppingunits.

• There must be two non-food units between every new restaurantortake-away

• Theproximityofaschoolorlocalauthorityleisurecentre canbetakenintoconsiderationinallnewapplicationsfor aFFO

• NewFFOswillonlybeconsideredintowncentresorretail areasandnotinresidentialareas.

Theattempttolinkpublichealthandplanningisfarfrom over,buttheoutcomessofarshowwhatcanbeachievedin attemptingtoinfluencethehealthofanareabyafocusonthe upstreamelementsofplace.Aswellastheplanningsystem developmentsoutlinedabovethelocalandhealthauthorities supportedworkwithexistinglocalfastfoodoutlets52

includ-ing:

• ReviewingtheCouncil’sowncommerciallettingpoliciesto promotehealthierfoodonsaleinlocalretailcentres. • Undertakingasocialmarketingprogramme tohelp

over-comeperceivedbarrierstohealthyeatinginTowerHamlets, includingidentifyinghealthyoptions.

• Trainingforownersonraisingawarenessandhowto pro-ducehealthyfood.

• Thedevelopmentofanawardsscheme.49

Thismulti-prongedapproachisnecessarytoaddressthe existingsituationandtoplanforthefutureopeningand con-trolofnewFFOs.Thisincludesworkingwithfast-foodowners toimprovethenutritionoftheirproductsaswellaspromote healthier optionsandsmallerportionsizeaswellas work-ing with suppliers ofsauces and processedmeat products tochangethecompositionoffoodatsourceor‘upstream’.49

Manyofthefastfoodoutletsintheborougharesmall inde-pendentoperatorsandownedbymembersofethnicminority communities.Intacklingtheissuesthereisaneedtowork withthesesmallindependentoperatorstohelpthemimprove their foodofferand notdisadvantagethem.There are few chainoutletsinresidentialareasoftheborough,thenational and internationalbrandchainsbeinglocatedcentralinthe southoftheborough,anareawhichhasabusinessdistrict. This constitutes anequalities issue as restrictionson new openingsmaydisadvantagethose smalland mediumscale entrepreneurs,oftencomingfromthelocalcommunity,while majorchainscansitouttheprocessand/orappealanylocal regulation.

Discussion

InLondonthemajorthrustforusingplanningprocessesto controlthefoodenvironmenthasbeentakenbylocal author-ities.Somelocalauthoritiesarebeginning toaddressthese

issues, perhapsthemostpublicised beingWaltham Forest, inthe northeast ofLondon,taking stepstoban new out-lets within400m of a school, and others such as Barking andDagenham,intheeastofLondon,developingnewlocal supplementary guidance (http://www.healthyplaces.org.uk/ case-studies/barking-dagenham/accessed8th Sept)aswell as the proposal to introduce a £1000 levy to be used to tacklechildhoodobesityintheborough.Sothereareattempts towards health promoting development at the local level within London and indeed across England. There is no nationalguidance on food orfast food outletsinthe local environment, therefore leaving those authorities who are interestedintacklingtheissuetodeveloptheirown.

Inordertomakethecaseforusingplanningtopromotea salutogenicandweakentheobesogenicenvironment,itis use-fultobringdevelopmentselsewheretotheattentionoflocal decision-makersaswasthecaseinTowerHamlets. Provid-inglocaldataonthescaleoftheproblembroughtawareness oftheproblembutnotnecessarilyofthesolutions.Theuse ofpublichealth ‘law’ iswell establishedin controllingthe availabilityofitemssuchasalcohol,tobacco50.SamiaMair

andcolleagues51intheUSexaminedhowzoninglawsmight

beusedtorestricttheopeningofFFOs.Planningcanemploy incentives,performanceorconditionalzoning.52Performance

zoningtakesaccountoftheeffectsoflanduseonthelocal areaandcommunity.Specificwaysofachievingthisinclude banningandorrestricting:

• FFOsand/ordrivethroughoutlets.

• ‘Formula’outlets(formulacanbedefinedbroadlytoinclude localtake-waysthathaveoneormoreoutletsornarrowly toincludeonlylargernationalchains).

• FFOsincertainareasor bydirectivesspecifyingdistance fromschools,hospitals.

• Byusingquotasincertainareaseitherbynumberofshop frontageorbyuseofdensity.

• Restrictingopeninghours.

• Makingthelinkbetweenregistrationforfoodhygieneand licensingmoreexplicit.

• Introducinglabellinginfastfoodoutlets.

• Using‘choiceediting’andspecifyingthenutrientcontent offood sold,sothechoiceismadebeforethe consumer purchases.

The implementation of such restrictions may seem far fetchedinEngland,yetLosAngeleshasbannedtheopening ofFFOsincertainareasforayear.TheLosAngelesinitiativeis ananti-obesitymeasureastheyfoundthattherewasa con-centrationofFFOsinpoorareas.53NewYorkCityisdistinctive

asaworldcityputtinginplacewide-ranging publichealth policywhichincludesadeliberatefocusonregulatory meas-ures as the context forhealth promotion.54,55 Itsplanning

strategyinrespectofFFO hasattracted attentionfor com-pulsorycalorielabellingofmenuitemsinchainshaving15 ormoreoutlets.Thiscanassistconsumerstomakehealthier choices,butitiscrucialtoseethatthisissetwithinabroad framework which shapes the food environment to ensure accesstohealthierfood.56HencetheNewYorkthecity-wide

ban on trans-fats and requirement for nutritionstandards for all public food procurement has upstream impacts on

the population not just individuals able to make healthy choices.Approachesandpoliciesnotadoptedortaken-upin London.

The ObesCities Report, a comparative study of policies developedinNewYorkandLondontotacklechildhood obe-sitynotedthewide-rangingandrobustapproachtakeninNew Yorkinrespectoffastfoodoutlets.57Thefirst

recommenda-tion ofthe ObesCitiesReportwastouselanduse planning powerstocontroltakeaways.Thiswouldinclude“zoningand landusereview,taxincentivesandcityownedproperty”to shapethespatialdistributionofhealthierfoodoutlets. Com-mentingatthereport’slaunch,Boris Johnson,theMayorof London,declaredwaronjunkfoodfirmssayingthat‘fastfood exclusionzonescouldbesetuparoundschoolsandinpartsofthe citywithanobesityproblem.’Headdedthat‘Asuperb2012legacy forLondonwouldbetheobliterationofchildhoodobesity.Ihopethat workingwithNewYorkwillresultinleaner,fitter,childrenand fam-iliesinbothcities.Iwanttotakeonthefastfoodcompanieswho mercilesslylurechildrenintoexcessivecalorieconsumption’.58As

theMayorisresponsibleforpan-Londonspatialplanning, gen-eralplanningpolicy,pan-Londonpublichealthpolicymightbe expectedtoprovideaframeworkforimprovingthefood envi-ronmentinrespectoftakeaways.InNovemebr2012theMayor launchedatoolkit’forfastfoodoutlets.Thisstoppedshortof developingapan-Londonperspectiveonfastfoodlocationand regulationorofrecommendingthedevelopmentofexclusion zonesaroundschools.Insteaditofferedguidanceto individ-ualboroughstodeveloptheirownapproachestotacklingthe problem.59

AtthetimeofwritingtheUKgovernmentareproposing changes to the planning system to make it less bureau-craticandmorebusinessfriendly(http://www.communities. gov.uk/news/corporate/1871021, accessed 3rd September 2012).Thishasbeenseenbysomeasbeingsympathetictobig businessesandmakingiteasierforthemtogainpermission to open outlets whilecutting back on localaccountability. WhiletheexistingEnglishplanning guidancefortown cen-tres does not specifically address the issue oftake-aways, it doesincludeasectiononhealthimpactassessmentand food which statesthat ‘[T]here will be a benefitto peopleon lowerincomesthroughimprovedaccesstogoodqualityfreshfood and other local goods and services at affordable prices. This is becausethenewimpacttest willbetterpromoteconsumerchoice and retail diversity helping to control price inflation, improving accessibilityandreducingtheneedtotravel’.Nevertheless,there isnolegalrequirement forplanningauthoritiestogaugethe healthimpactofanewbusiness.Thenextsectionaddresses whetherthepublichealthlandscapeprovidesaframeworkto promotehealthyfoodenvironments.

The public health landscape is changing in Englandat national, regionaland locallevels, withmuch implementa-tion due to comeon stream from April 2013. Heralded as putting communities, families and individuals in the driv-ingseatforpolicymaking,thepublichealthfunctionisbeing devolvedtolocalauthorities.Thisisintendedtoenableaction onsomeofthesocialdeterminantsofhealthtobebrought togethertopromotehealthandwellbeing.Localpolicy forma-tionistobesupportedbynationalpolicybasedonvoluntary agreementswiththefoodindustry–TheResponsibilityDeal (seehttp://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk,accessed10thJanuary

2013).Therearenomandatestoregulatethroughplanning, butthereisaproposalwhichhasrelevancetothefastfood industry:acaloriereductionpledge.Actionstoaddressthis proposalmight includereformulation ofproductsto make themlessenergydense,reduceportionsizesandprovide calo-rielabellingtoinfluenceconsumerchoice.Todatethemain focushasbeenonretailersandnotFFOs.Anotherissuearising fromtheresponsibilitydealsisthattheymainlyinvolvelarge nationalandmulti-nationalcompaniesandnotsmall inde-pendentoutletslikethemajorityofFFOsintheTowerHamlets casestudyabove.AnotherkeypointtonoteaboutthePledges andtheResponsibilityDealisthattheyarevoluntary agree-ments.Itisrecognisedthattheeffectofvoluntaryagreements islimited.60Therelocationofpublichealthtolocalauthorities

givesthemanadvantageinthattheyareclosertothe plan-ningsystemandcould,liketheearlypioneersofpublichealth, takeadvantageofthisrelocation.

ThelegislationforpublichealthinEnglandincludesthe establishmentofaLondonHealthImprovementBoard(LHIB), toberunbytheMayorandthe33LondonLocalAuthorities workingtoaddvaluetothepublichealthactivitiesofthose localauthorities.Alsoithasbeenagreedthatchildhood obe-sityistobeoneofitsfourpriorities.Withaprimaryfocuson aHealthySchoolsprogramme,ithasproposedasetofnine keytasks,developedfollowingworkshopswithstakeholders whichincludedvigorousdebate.Oneofthenineprioritytasks throughMarch2014isto“Changethefoodenvironmentin Londontosupporthealthierchoices–workinginpartnership withtheLondonFoodBoardandothers”.Componentsofthis taskincludeundertakingsinthreeareas:

1. “Support localauthoritiestouseexisting planning pow-erstorestricttheopeningoftakeaways,especiallycloseto schools”;

2. Extendthe“HealthyCateringCommitments”programme whichprovidesawardstoeatingestablishmentswhich vol-untarilymeetgivennutritionalstandards;

3. Take stepsto “increasethe availability offruitand veg-etables inconveniencestores...”(http://www.lhib.org.uk/ attachments/article/101/2b-Child%20Obesity.pdf,accessed 14Sept2012).

NoneoftheLHIBproposedworkprogrammecallsfor addi-tionalpan-Londonornationalplanningpowers.However,two elementsofthepreliminaryplanningmayprovideabasisfor atleastdiscussingtheneedforpan-Londonandnational reg-ulation:

FirstthedevelopmentoftheLHIB’svision,aimsand deliv-eryprincipleshas“includedananalysisoftheapproachtaken inNewYorkCitytotackleobesity,itsimpact,andthelessons Londoncanlearn.Atastrategiclevel,thisincludestheneed forsharedvisionandcommitmentfrom seniorleadersand influentialfigures;andthedevelopmentofboldproposalsthat stimulatedebateamongleadersandcommunities”.

Second“Considerationofequityissues isacorepart of thiswork,andahealthinequalitiesimpactassessmentwill bedevelopedtoaccompanythefinalworkplan.”

Thereispotential,thereforeforthework oftheLHIB to beopentonewlearningaboutbestpracticefromelsewhere. InthecontextoftheLondon-centricfocusofpoliticiansand

the media in England, such learning might lead to useful spin-offs forother localities.Any work on take-aways and fastfoodneedstobesetinthecontextofhow,whereand whypeopleaccessfoodassetoutinarecentreportfromthe AmericanPlanningAssociationwhowarnofthedangersof allowingobesogenicandunhealthysituationstodevelop,and thenexpectingthathealthpromotionorplanningcantackle theproblems.61

Conclusion

Wecontendthatlong-termoptionsarebestpursuedthough the introduction ofcentralenabling legislation whichlocal governmentauthoritiesandlocalhealthagenciescanadopt. When addressing whole system problems, such as those resulting from an obesogenic environment, local policy-makingisnecessarybutnotsufficient.Planningonitsown cannot address the total problem. Other upstream inter-ventionsacting onsocialdeterminantsofhealthemployed elsewhereincludingtaxesandsubsidiesprovideincentivesto boththoserunningFFOsandcustomers.57,62

SuccessivenationalgovernmentsinEnglandhavenotput intoplaceatthenationallevel,socialdeterminantsinformed health promotion infrastrucure that would engage speed-ily and effectively withunhealthy food environments. The defaultpositionconsistentwiththeemergingpublichealth landscapeinEnglandrunsthedangeroffurther disadvantag-ingtheverycommunitiesmostatrisk.

Many public health analysts welcome empowered decision-making at the local level, which is promised in the emerging public health policy in England, in contrast withwhollytop-downpolicyformation.Topdowndecision makingmightgivelittlescopeforshapinginitiativesinline with distinctive demographic and epidemiological assess-mentandjudgementbycivilsocietygroupsandcommunities of practice. While existing planning legislation in London and Englandis weakinprotecting citizens andfor provid-ing salutogenic environments, it does offer opportunities. This article has shown how in Tower Hamlets and many other localitiesinbothLondon andacrossEnglandthereis enthusiasmtocontrolthe localfoodenvironmentand that linkscanbemadeacrossformalpublichealthservicesand localauthorityplanning servicestomovetowardsahealth promotingpublichealthstrategy.Wewouldnotwanttoclaim successforalltheactivitiesundertakensinceourworkbut would make someclaim to this being the ‘kickstart’ fora body ofwork ranging from activities with localowners of outlets,reformulationoffoods, thetraining offood service staff, a registration scheme and the development of local planningguidance.Thelessonsfromthisresearchhavebeen usedtoinformsimilar processesinareassuchasGlasgow, Liverpool/MerseysideandBelfast.63,64

Movestowardsnewandmorepowerfullegislationrelated tothe foodenvironmentmust graspthe currentpotentials andlimitationsoftheplanningsystem.Thisknowledgeand skillbasemustbesharedbylocalpoliticians,planners, busi-nessesandcommunities.Inthiscontextspiritedimpetusto support local authorities is being provided bycivil society groups. For instance, The National Heart Forum, an

influ-ential civil society alliance of national organisations, has stepped in to provide background information on how to use planning.Itsrecent report devoted tolocalauthorities describesthe planning system, outlineshow planning can beusedforpublichealthandspecifiesspecificmechanisms andprocesseswhichcanbeused.65Inadditionithasin2012

setupanon-lineresource,HealthyPlaces,toprovide what hashithertobeenverydifficulttoaccess,acompendiumof successfulcasestudies(seehttp://www.healthyplaces.org.uk/ key-issues/hot-food-takeaways/development-control/).

Whilelegislativesystemsdiffer,the USexperience mer-itsfurtherconsiderationinthecontext ofEnglishplanning laws.TheinitiativesinNewYorkCityaswellasbeing anti-obesitymeasuresare alsodesignedtoaddress the issueof wideninginequalities.ItisnotablethatwhileNewYorkadopts informationalbehaviourchangeinitiativesasinthecaseof calorielabelling,thisiswithinapolicyportfoliowithastrong presenceofregulation.Thisapproachhasbeencreditedwith “NYCity’slifeexpectancyrisingfasterthananywhereelsein theUSA”andattributedtothe“...city’saggressiveeffortsto reshapeNewYork’ssocialenvironment...”amovementledby thecity’spublichealthdepartmentwithforcefulbackingfrom itsMayor.66

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorshavenoconflictsofinteresttodeclare.

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. Foresight.Tacklingobesities:futurechoices—projectreport. London:TheStationeryOffice;2007.

2. SwinburnBA,SacksG,HallKD,McPhersonK,FinegoodTD, MoodieML,etal.Theglobalobesitypandemic:shapedby globaldriversandlocalenvironments.Lancet.

2011;378:804–14,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60813-1.

3. DietzWH,BenkenDE,HunterAS.Publichealthlawandthe preventionandcontrolofobesity.MilbankQuart.

2009;87:215–27.

4. SallisJF,GlanzK.Physicalactivityandfoodenvironments: solutionstotheobesityepidemic.MilbankQuart. 2009;87:123–54.

5. MelloM.NewYorkcity’swaronfat.NEnglJMed. 2009;360:2015–20.

6. FinerSE.ThelifeandtimesofSirEdwinChadwick.London: MethuenandCo;1952.

7. RiddeV,CloosP.Healthpromotion,powerandpolitical science.GlobalHealthPromot.2011;18:03–4.

8. RaynerG,LangT.Isnudgeaneffectivepublichealthstrategy totackleobesity?No.BrMedJ.2011;342:d2177(Clinical ResearchEd.).

9. DepartmentofHealth.Thepublichealthresponsibilitydeal; 2011.Availableat:http://responsibilitydeal.dh.gov.uk/ [accessed10.09.12].

10.SunsteinC,ThalerR.Nudge:improvingdecisionsabout health,wealth,andhappiness.Yale:YaleUniversityPress; 2008.

11.WorldHealthOrganization.TheOttawaCharter.Geneva: WHO;1986.

12.NutbeamD.Healthpromotionglossary.Geneva:WHO;1998.

13.WorldHealthOrganization.Closingthegapinageneration: healthequitythroughactiononthesocialdeterminantsof health.Geneva:WHO;2008.p.16.

14.McDonaldsandAllegraStrategies.EatingoutintheUK2009: acomprehensiveanalysisoftheinformaleatingoutmarket. London:Allegra;2009.

15.PopkinB.Theworldisfat:thefads,trends,policiesand productsthatarefatteningthehumanrace.NewYork:Avery; 2009.

16.LinBH,GuthrieJ.Thequalityofchildren’sdietsatandaway fromhome.FoodRevUSDA.1996;May–August:45–50. EconomicResearchService.

17.MacdonaldL,CumminsS,MacintyreS.Neighbourhod fast-foodenvironmentandareadeprivation-substitutionor concentration?Appetite.2007;49:251–4.

18.ReidpathDD,BurnsC,GarrardJ,MahoneyM,TownsendM. Anecologicalstudyoftherelationshipbetweensocialand environmentaldeterminantsofobesity.HealthPlace. 2002;2:141–5.

19.KavanaghA,ThorntonL,TattamA,ThomasL,JolleyD,Turrel G.VicLANES:placedoesmatterforyourhealth.Melbourne: UniversityofMelbourne;2007.

20.KwateNAO.Friedchickenandfreshapples:racialsegregation asafundamentalcauseoffast-fooddensityinblack

neighborhoods.HealthPlace.2008;14:32–44.

21.NationalConsumerCouncil.Takeawayhealth:howtakeaway restaurantscanaffectyourchancesofahealthydiet.London: NationalConsumerCouncil;2008.

22.Which?Fastfood:doyouknowwhatourkidsareeating? Which?;2009.October,p.66–8.

23.BurnsC,InglisAD.MeasuringfoodaccessinMelbourne: accesstohealthyandfast-foodsbycar,busandfootinan urbanmunicipalityinMelbourne.HealthPlace.

2007;13:877–85.

24.MorlandK,WingS,DiezRouxA,PooleC.Neighbourhood characteristicsassociatedwiththelocationoffoodstoresand foodserviceplaces.AmJPrevMed.2002;22:23–9.

25.DowlerE.Policyinitiativestoaddresslow-income households’nutritionalneedsintheUK.ProcNutrSoc. 2008;67:289–300.

26.NelsonM,ErensB,BatesB,ChurchS,BoshierT.Lowincome dietandnutritionsurvey.London:FoodStandardsAgency; 2007.

27.Sodexho.TheSodexhoschoolmealsandlifestylesurvey 2005:Whyteleafe.Surrey:Sodexho;2005.

28.HendersonL,GregoryJ,SwanG.NationalDietandNutrition Survey:adultsaged19to64years:volume1:typesand quantitiesoffoodsconsumed.London:TSO;2002.

29.PrenticeAM,JebbSA.Fast-foods,energydensityandobesity: apossiblemechanisticlink.ObesRev.2003;4:187–94. 30.CounS.Deprivationamplificationrevisited:or,isitalways

truethatpoorerplaceshavepooreraccesstoresourcesfor healthydietsandphysicalactivity?IntJBehavNutrPhys Activ.2007;4:32,http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-4-32. 31.MelaniphyJ.Therestaurantlocationguidebook,a

comprehensiveguidetopickingrestaurantandquickservice foodlocations.Chicago:InternationalRealEstateLocation InstituteInc;2007.

32.BowyerS,CaraherM,EilbertK,Carr-HillR.Shoppingforfood: lessonsfromaLondonborough.BrFoodJ.2009;111:452–74. 33.SinclairS,WinklerJT.TheSchoolFringe:whatpupilsbuyand

eatfromshopssurroundingsecondaryschools.London: NutritionPolicyUnit,LondonMetropolitanUniversity;2008. 34.AustinSB,MellySJ,SanchezBN,PatelA,BukaS,Gortmaker

SL.Clusteringoffast-foodrestaurantsaroundschools:a novelapplicationofspatialstatisticstothestudyoffood environments.AmJPublicHealth.2005;95:1575–81, http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2004.056341.

35.DayPL,PearceJR.Obesity-promotingfoodenvironmentsand thespatialclusteringoffoodoutletsaroundschools.AmJ PrevMed.2011;40:113–21.

36.NewEconomicsFoundation.Aninconvenientsandwich:the throwawayeconomicsoftakeawayfood.London:New EconomicsFoundation;2010.

37.CaraherM,LloydS,MadelinT.The‘schoolFoodshed’:schools andfast-foodoutletsinaLondonborough.BrFoodJ.2013. DOIinformationunavailable.

38.LloydS,CaraherM,MadelinT.Fishandchipswithaside orderoftransfat:thenutritionimplicationsofeatingfrom fast-foodoutlets:areportoneatingoutinEastLondon. London:CentreforFoodPolicy,CityUniversity;2010. 39.LloydS,MadelinT,CaraherM.Reportonfastfoodoutlets

(FFOs)inTowerHamlets:aboroughperspective.London: CentreforFoodPolicy,CityUniversity;2008.

40.ThomasG.Howtodoyourcasestudy:aguideforstudents andresearchers.London:Sage;2010.

41.CityUniversityofNewYork,LondonMetropolitanUniversity. AtaleoftwoObesCitiescomparingresponsestochildhood obesityinLondonandNewYorkCity;2010.

42.GreaterLondonAuthority.RoundpopulationprojectionPLP low.London:GLA;2007.

43.DenchG,GavronK,YoungM.TheNewEastend:kinship,race andconflict.London:ProfileBooks;2006.

44.TowerHamletsPCT.Annualpublichealthreport.London: TowerHamletsPCT;2007.

45.OFSTEDTellus2Survey;2007.http://www.ofsted.gov.uk/ [accessed26.07.08].

46.IpsosMORI.Facetofacerandomprobabilitysurveyof2342 respondentsaged16andovercarriedoutinTowerHamlets onbehalfofthelocalNHStrust.London:IpsosMORI;2009. 47.SchoolFoodTrust.Junkfoodtemptationtownsindex.

London:SchoolFoodsTrust;2008.

48.AmericanInstituteforCancerResearch.Worldactivity,and thepreventionofcancer:aglobal,perspective.Washington: CancerResearchFund/AmericanInstituteforCancer Research;2007.

49.SandelsonM.TowerHamletsFoodforHealthAwardProject March2009–March2012.London:TowerHamletsPublic HealthDirectorate;2012.

50.BrownellK,WarnerK.Theperilsofignoringhistory:big tobaccoplayeddirtyandmillionsdied.Howsimilarisbig food?MilbankQuart.2009;87:259–94.

51.SamiaMairJ,PierceM,TeretS.Theuseofzoningtorestrict fastfoodoutlets:apotentialstrategytocombatobesity.USA: TheCenterforLawandthePublic’sHealthatGeorgetown andJohnsHopkinsUniversities;2005.

52.SamiaMairJ,PierceMW,TeretSP.Theuseofzoningto restrictfastfoodoutlets:apotentialstrategytocombat obesity.TheCentreforLawandPublicHealth,JohnsHopkins University;2005.

53.ReutersLosAngles.CityCouncilpassesfastfoodban. Availableonhttp://www.reuters.com/

article/healthNews/idUSCOL06846020080730[accessed 29.08.08].

54.NewYorkCityDepartmentofHealthandMentalHygiene. Healthyheartavoidtransfat.Availableon

http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/cardio/cardio-transfat. shtml[accessed29.08.08].

55.DinourL,FuentesL,FreudenbergN.ReversingobesityinNew YorkCity:anactionplanforreducingthepromotionand accessibilityofunhealthyfood.NewYork:CityUniversityof NewYorkCampaignagainstDiabetesandthePublicHealth AssociationofNewYorkCity;2009.

56.AsheM,JerniganD,KlineR,GalazR.Landuseplanningand thecontrolofalcohol,tobacco,firearmsandfastfood restaurants.AmJPublicHealth.2003;93:1404–8.

57.FreudenbergN,LibmanK,O’KeefeE.AtaleoftwoObesCities: theroleofmunicipalgovernanceinreducingchildhood obesityinNewYorkandLondon.JUrbanHealthBullNY AcadMed.2010.

58.CrerarP.Growyourownschooldinnerstobeatobesity,says BorisJohnson.EveingStandard.2010,25thJanuary.Available on http://www.standard.co.uk/news/grow-your-own-school-dinners-to-beat-obesity-says-boris-johnson-6710610.html [accessed10.01.13].

59.TheMayorofLondon.Takeawaystoolkit:tools,interventions andcasestudiestohelplocalauthoritiesdeveloparesponse tothehealthimpactsoffastfoodtakeaways.London:The GreaterLondonAuthority;2012.

60.SharmaL,TeretS,BrownellK.Thefoodindustryand self-regulation:standardstopromotesuccessandtoavoid publichealthfailures.AmJPublicHealth.2010;100: 240–6.

61.HodgsonK.Planningforfoodaccessandcommunity-based foodsystem.US:AmericanPlanningAssociation;2012. 62.MyttonOT,ClarkeD,RaynerM.Taxingunhealthyfoodand

drinkstoimprovehealth.BMJ.2012;344:e2931.

63.GlasgowCentreforPopulationHealth.Areschoollunchtime stay-on-sitepoliciessustainable?Afollow-upstudy.Briefing paper33.GlasgowCentreforPopulationHealth:Glasgow; 2012.

64.StevensonL.Practicalstrategiestoimprovethenutritional qualityoftake-awayfoods.In:PresentationatHeartof Merseysideconference‘TakeawaysUnwrapped’Developing LocalPolicy:healthierfoodandthe‘informaleatingout’ sector.2011.

65.MitchellC,CowburnG,FosterC.Assessingtheoptionsfor localauthoritiestousetheregulatoryenvironmenttoreduce obesity.London:TheNationalHeartForum;2011.

66.AlcornT.RedefiningpublichealthinNewYorkCity.Lancet. 2012;379:2037–8.