FUNDAÇÃO GETULIO VARGAS

ESCOLA DE ADMINISTRAÇÃO DE EMPRESAS DE SÃO PAULO

MARIANA APARECIDA CALABREZ ORENG

BANK RESPONSES TO CORPORATE REORGANIZATION Evidence from Brazil

SÃO PAULO 2017

2

MARIANA APARECIDA CALABREZ ORENG

BANK RESPONSES TO CORPORATE REORGANIZATION Evidence from Brazil

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração de Empresas

Campo de conhecimento: Finanças Corporativas

Orientador: Professor Doutor Richard Saito

SÃO PAULO 2017

3 Oreng, Mariana Aparecida Calabrez.

Bank responses to corporate reorganization : evidence from Brazil / Mariana Aparecida Calabrez Oreng. - 2017.

41 f.

Orientador: Richard Saito

Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo.

1. Empresas - Reorganização. 2. Falência - Brasil - Estudo de casos. 3. Sociedades comerciais - Reorganização. 4. Bancos - Brasil. I. Saito, Richard. II. Dissertação (mestrado) - Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo. III. Título.

4

MARIANA APARECIDA CALABREZ ORENG

BANK RESPONSES TO CORPORATE REORGANIZATION Evidence from Brazil

Dissertação apresentada à Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo da Fundação Getulio Vargas, como requisito para obtenção do título de Mestre em Administração de Empresas

Campo de conhecimento: Finanças Corporativas

Orientador: Professor Richard Saito, PhD Data de Aprovação: ____/____/____

Banca examinadora:

____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Richard Saito (Orientador)

FGV-EAESP

____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Paulo Renato Soares Terra

FGV-EAESP

____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Vinicius Augusto Brunassi Silva FECAP-SP

5

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I would like to express my gratitude towards my adviser, Professor Richard Saito, for his guidance and constant supervision. My thanks and appreciations also go to Professor Vinicius Brunassi, for his patience and collaboration, and to Professor William Eid for collaborating in my training as a researcher. I would like to express my special gratitude and thanks to my husband, for his support and partnership along this journey and also thank my parents and my brother for being always by my side. I would like to acknowledge the financial support of ANBIMA with the award of a Postgraduate Research Studentship entitled “XII Prêmio ANBIMA de Mercado de Capitais”. It is an honor for me to outstand among so many dedicated students and to be recognized by such an excellent institution.

6

AGRADECIMENTO

Agradeço ao meu orientador, Prof. Dr. Richard Saito, pelo apoio ao meu desenvolvimento durante esta jornada. Agradeço também ao Professor Vinicius Brunassi, pela paciência e colaboração, e ao Professor William Eid pela colaboração na minha formação como pesquisadora. Um agradecimento especial ao meu marido pela parceria, por me encorajar e me apoiar. Também agradeço aos meus pais e ao meu irmão, por estarem sempre ao meu lado.

Gostaria de agradecer o apoio financeiro da ANBIMA com a concessão de uma Bolsa de Estudos de Pesquisa de Pós-Graduação intitulada "XII Prêmio ANBIMA de Mercado de Capitais". Sinto-me honrada por ser escolhida entre tantos estudantes dedicados e ser reconhecida por uma instituição tão excelente.

7 ABSTRACT

This study analyzes how bank creditors vote on corporate reorganization filings. Brazil offers an excellent scenario for bankruptcy research: on the 10th anniversary of the Brazilian Bankruptcy Code, the number of reorganization filings skyrocketed, increasing from 110 in 2005 to 1863 in 2016. Our work is both theoretical and empirical; we suggest a cooperative game setting to explain creditor behavior, and we apply pooled cross-sectional data from 125 reorganization filings in Brazil from 2006 to 2016. We find evidence that the haircut proposed by debtors is the main factor driving bank creditors’ decisions, rather than firm size or age, as the traditional literature proposes. In accordance with our theoretical model, the proportion of senior debt is not relevant in explaining bank responses to reorganizations. By employing a unique dataset, we contribute to the bankruptcy literature by showing that the unified creditors’ framework does not apply. By looking at bank conflict at the interest level, we verify that the approval rate for reorganization filings decreases sharply, which indicates that coordination failures result from negotiation problems and often lead to liquidation. Due to legal and process similarities with countries such as the United States and Canada, the study also offers important insights regarding bankruptcy cases in general.

8 RESUMO

Este estudo explora como bancos credores votam em processos de recuperação judicial. O Brasil oferece um excelente cenário para este tipo de pesquisa: no décimo aniversário da Lei de Falências, o número de pedidos de reorganização aumentou de 110 em 2005 para 1863 em 2016. Este trabalho é teórico e empírico: Sugerimos um cenário de jogo cooperativo para explicar o comportamento dos credores e utilizamos dados agrupados de corte transversal de 125 registros de recuperação no Brasil de 2006 a 2016. Encontramos evidências de que a margem de redução proposta pelos devedores é o principal fator que pesa na decisão dos credores bancários, ao invés do tamanho da empresa ou seu tempo de mercado, como sugere a literatura tradicional em falências. De acordo com o modelo teórico proposto, demonstra-se que a proporção da dívida sênior não é relevante para explicar as respostas dos bancos credores às recuperações. Ao empregar um conjunto de dados exclusivo, este estudo contribui para a literatura de falências mostrando que a ideia de credores unificados não se aplica. Ao analisar o conflito entre bancos credores no nível da empresa, verifica-se que a taxa de aprovação de pedidos de recuperação diminui acentuadamente em casos de conflito, o que indica que as falhas de coordenação resultam de problemas de negociação e muitas vezes levam à liquidação. Devido a semelhanças legais e processuais a países como os Estados Unidos e Canadá, o estudo também oferece novas percepções sobre casos de falência em geral.

Palavras-chave: falências, recuperação judicial, classes de credores, modelo de barganha de credores

9 CONTENTS

1. INTRODUCTION 10

2. PRIOR LITERATURE 11

2.1 Corporate reorganization process in Brazil 14

3. THEORETICAL MODEL 15

4. DATA ANALYSIS 18

5. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY 24

6. CONCLUSION 27

7. REFERENCES 27

8. TABLES, LISTS AND FIGURES 30

10 1. INTRODUCTION

According to Jackson (1982), most of the bankruptcy process concerns creditor distribution questions rather than discharge of the debtor. Along these lines, reaching a common agreement between creditors and debtors is crucial to reorganization filings. Because banks and secured institutional lenders are those creditors who are typically able to influence corporate policies (James, 1995), our goal is to assess the role of financial creditors during corporate reorganizations. The question under investigation is, “how do bank creditors vote on corporate reorganization filings?” The secondary question involves how creditors vote based on seniority.

We propose a cooperative game setting to understand bank creditor decision-making, which suggests that the total amount of debt and the proportion of senior debt are not significant in explaining bank behavior. We examine the types of interventions made during creditors’ meetings and the cases in which there were conflicts between bank creditor classes. Then, we empirically test those factors that are associated with banks voting in favor of reorganization.

This study adds to the bankruptcy literature by offering important insights to the creditors’ bargain model and by employing a unique dataset that was not previously available that contains bankruptcy court documents from 125 corporate reorganization filings in Brazil from 2006 to 2016. In sum, our results demonstrate that the haircut proposed by the debtor is the main factor driving bank creditors’ decisions rather than firm size or age, as the traditional literature proposes. We provide novel evidence that the unified creditors’ framework does not apply: when there is a conflict between bank creditors, the approval rate on reorganization filings decreases sharply. Indeed, our regression results demonstrate that conflict is associated with banks voting in favor of liquidation, regardless of creditor class. As the result of legal and process similarities with countries such as the United States and Canada, this study also offers important insights regarding bankruptcy cases in general.

This research is timely for a variety of reasons. First, recent bankruptcy studies have shifted the focus away from equity and managerial control to creditor behavior. These

11

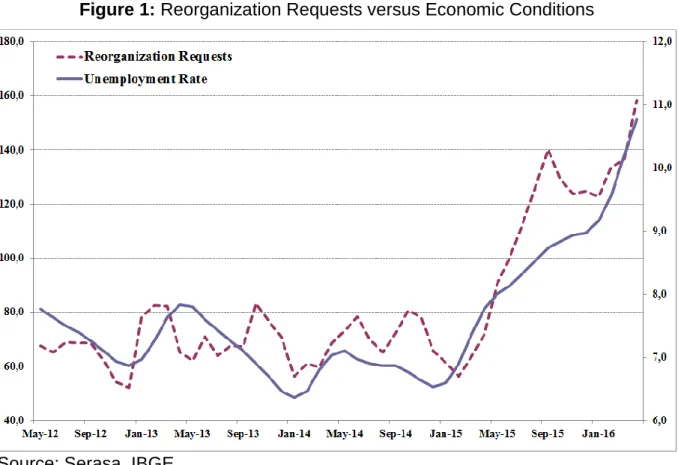

studies demonstrate that senior lenders use several strategies to limit the bargaining position of holders of subordinated debt during reorganizations (Branch and Ray (2007), Ayotte (2009)), which reinforces the need to study the conflicts between creditor classes. Second, the number of corporate reorganization filings in Brazil increased from 252 to 828 between 2006 and 2014, which amounts to an increase of approximately 14% per year. In 2015, due to Brazil’s economic crisis, this number has jumped to 1287, which represents an increase of 55% in only one year. Although some practitioners argue that some of these filings are only precautionary measures, the increase is significant, and the data demonstrate that the number of reorganization requests has closely followed the deterioration of economic conditions (see Graph 1).

The paper proceeds as follows: the next section reviews the previous literature, and we present our theoretical model in the third section. The fourth section describes the data, and the fifth section provides our empirical analysis. The conclusion and references follow.

2. PRIOR LITERATURE

Many authors argue that reorganization is a two-stage game (Bulow and Shoven (1978), White (1981), Fama (1985), Fisher and Martel, 1995)). In the first stage, firms decide whether to file for reorganization. Once a reorganization procedure is chosen over liquidation, “there is a conflict between the secured creditors’ right to claim their collateral versus the goal of reorganizing the firm” (Araujo and Funchal, 2005). In stage two, creditors bargain and vote in favor or against the reorganization.

Despite the fact that bankruptcy law is designed to avoid coordination problems and contract incompleteness, Jackson (1982) argues that “bankruptcy law’s beguiling slogan has been little more than a banal reminder that equals are to be treated equally in bankruptcy: the important determination of who those equals are is often not resolved under bankruptcy law.” Thus, in his view, bankruptcy proceedings are at the back end of the creditors’ bargain model. In fact, several studies have demonstrated that deviations from the absolute priority rule occur in practice (Franks and Torous (1989), Eberhart et al. (1990), Weiss (1990)). In Germany, a financial

12

institution is appointed to mitigate the risk of uncoordinated creditor action (Bankenpool). However, we find no documentation of such an instrument in Brazil or the United States. In this sense, bank creditors’ bargaining is a coordination problem (Brunner and Kahnen, 2008).

Branch and Ray (2007) argue that subordinate debtholders have considerable leverage in the bankruptcy negotiation process due to courts’ bias toward obtaining consensual plans and their ability to block or delay confirmation of a plan that provides subordinate debtholders with little or no recovery. Secured debtholders, on the other hand, can obtain a recovery in liquidation, which provides nothing for junior creditors. Despite the fact that bankruptcy laws are written in such a way that the Absolute Priority Rule should not be violated, senior creditors can use several strategies to limit the bargaining position of junior creditors, such as vote dilution, the enforcement of indenture provisions or by exercising control through stringent covenants. This bargaining between secured and unsecured creditors can distort the reorganization process. Ayotte (2009) argues that creditors with senior, secured claims have come to dominate the Chapter 11 process. These recent findings are contrary to Welch (1997), who proposes that bank debt is universally senior because if they [the banks] were unsecured, they would be better organized and could more strongly contest priority in cases of financial distress.

Studying how bank creditors behave during the reorganization process is useful for several reasons. First, companies do not rely on public issuance in some countries because their bond markets are stunted, making bank financing more important (Allen, Chui and Maddaloni, 2008). Second, some articles highlight the potential problems faced by distressed firms that have bank debt because banks can not only create regulatory difficulties to scale down the firms’ claims but can also be more difficult to obtain concessions from (James, 1995). Asquith and Scharfstein (1994) also argue that banks “do not play much of a role in resolving financial distress”, and real debt relief comes from subordinated creditors. The authors, however, rely on the same assumption made by Welch, namely that banks are predominantly senior and thus have an advantage in these negotiations.

13

Third, some studies provide evidence that banks and secured institutional lenders are the creditors who are usually able to influence corporate policies, rather than public bondholders or trade creditors (Gilson and Veytsupens, 2004). Finally, because firms usually have more than one bank as a creditor, one stream of literature highlights the issue of the size of the group of creditors and their role in a reorganization as a whole: Brunner and Krahnen (2008) demonstrate that while coordination among a smaller group of banks is associated with a higher probability of reorganization success, the opposite holds for an increased number of bank lenders because inefficiencies arise from the inability to renegotiate multiple debts. Franks and Sussman (2005), for their part, argue that debt dispersion can lead to coordination failures.

On the one hand, Chen, Weston and Altman (1995) hypothesize that when there is a group of “bank-type” lenders, “the parties will function according to a Coase Theorem [1937]”, which holds that they will work as one party seeking to maximize investment returns in their joint interest. Here, we understand that an agreement between parties implies an efficiency gain because it involves lower financial distress costs, as proposed by Bebchuk and Chang (1992). Thus, one should expect banks to display the same voting profile during creditors’ meetings. Kirschbaum (2009), on the other hand, argues that secured creditors will usually prefer to value the assets of a corporation being reorganized at something close to an amount that is sufficient to cover their own claims, without regard for other parties, which would make one assume that secured creditors do not necessarily cooperate. Gertner and Scharfstein (1991), for their part, offer a theoretical explanation for the mixed positions in the literature: when financial distress hampers operating performance, financial renegotiation is inefficient and the Coase Theorem fails. In this sense, one should expect non-successful reorganizations to be related to diminished coordination among lenders. We will address this debate empirically.

Bank behavior is a topic that is subject to considerable controversy, and the recent literature on bankruptcy has shifted the focus away from equity and managerial control and demonstrated that the unified, single-creditor framework is far from universal. Conflict therefore occurs because of the fundamental inefficiency of the

14

bankruptcy process: resource allocation questions (sell versus reorganize) are ultimately confounded with distributional questions (how much each creditor will receive) (Ayotte, 2009).

2.1 Corporate reorganization process in Brazil

Bankruptcy proceedings have two possible outcomes: reorganization or liquidation. Corporate reorganization is a legal tool to avoid bankruptcy and a shield with respect to the company’s payment obligations. In the United States, these mechanisms are referred to as Chapter 11 and Chapter 7 of the US bankruptcy code, respectively. In Brazil, the process is fairly similar and is coded in the Bankruptcy Code of 2005. It “offers more transparency in terms of procedures and offers stakeholders more control of the process. It also allows unsuccessful companies to regain credibility and reorganize their activities” (Practical Guide on Corporate Reorganizations, Federal Council of Administration – Brazil, 2011).

According to Article 50 of the Brazilian Bankruptcy Code (11.1001/2005), firms have at their disposal a total of 15 tools to structure a reorganization process. These tools are not exclusive and can be pursued at the same time. A table that lists all of these tools is provided in List 1.

According to the deadlines established by Brazilian law, from the approval and beginning of the implementation of a reorganization plan, a company can have up to 2 years to negotiate and settle its liabilities.1 Similarly, in the United States, the average Chapter 11 reorganization case takes 25 months to confirm the reorganization (Branch and Ray, 2007). For more information about the determinants of delays in corporate reorganizations, see Silva, Saito and Manoel (2015). To decide whether a company should be subject to reorganization or liquidation, the creditors meet at least once, and these meetings are attended by both workers and the creditors. In our sample, there are only 2 cases in which the workers voted against reorganization.

15 3. THEORETICAL MODEL

We identified several approaches in the literature to model bank behavior in response to corporate reorganizations. Some studies view the bargaining between creditors as a non-cooperative game (Annabi, Breton and Français, 2010), while others argue that this process can be depicted as a collective action problem or as a larger scale prisoner’s dilemma (Jackson (1982), Li and Li (1999), Fan and Sundaresan (2000)). A more recent study addresses the bankruptcy decision as the exercise of a real option, as claimholders have incentives to withhold information due to the length of the process (Baird and Morisson, 2001). For the purposes of this study, we approach the bargaining between creditors as a prisoner’s dilemma.

We define the game in the following way: the secured bank creditors are all represented by the player Senior, while the group of unsecured bank creditors is represented by the player Junior. Despite the fact that workers vote during creditors’ meetings, we exclude them from the formal representation. We do so because our court files demonstrate that workers usually vote in favor of reorganization (there were only two cases in which they did not), so we hypothesize they will not impact the final outcome of the negotiation. We assume symmetric information because at the moment a company files for bankruptcy, complete information is available to the creditors. The players have common knowledge, as all parameters are given ex ante.

The conflict of interest lies in the fact that when a company files for bankruptcy, its market value is lower than the total amount of its debt. Hence, the players know that their best interest will be maximized as long as they cooperate. Senior and Junior can approve or reject the reorganization plan proposed by management. We assume a single round, and in case no agreement is reached, a judge will define the outcome in the final round (Li and Li, 1999). The game is sequential, and for simplicity, we assume a common belief system with respect to the judge, such that the players assign a probability p of the judge deciding in favor of reorganization. This approach is derived from Annabi, Breton and François (2010), who take the judge’s behavior into account (although they work in a non-cooperative setting).

16

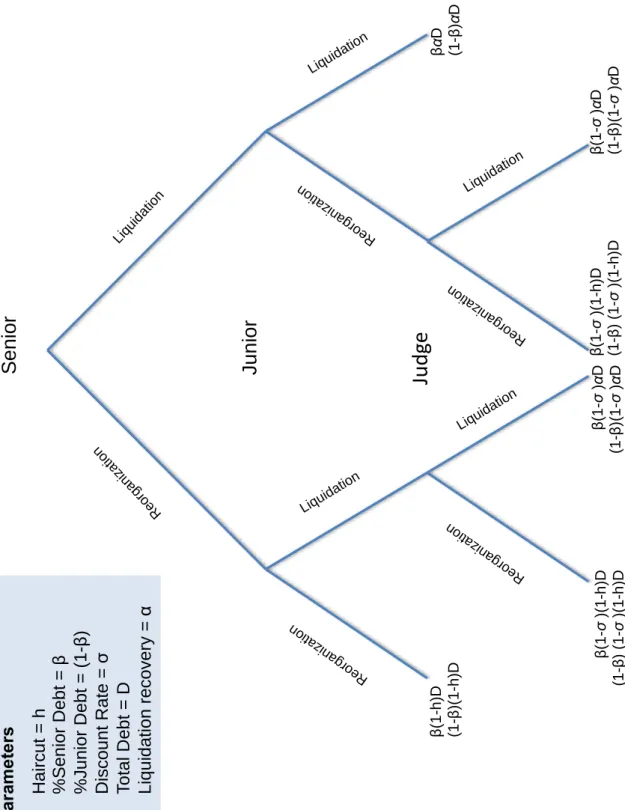

D represents the amount redeemable by all creditors at the beginning of the negotiation (t=1). J and S denote the players Junior and Senior, respectively, and β is the proportion of the total debt owned by senior bank creditors. Distressed companies tend to lose value as time passes and no action is taken. Moreover, covering all aspects of negotiations, such as the future use of the firm’s assets or how much and what type of securities the various creditors will receive, can result in a lengthy and costly procedure (Hotchkiss et al., 2008). In this sense, we assume that the amount redeemable by creditors decreases at a constant rate σ, which is our measure of the opportunity cost. For simplicity, we assume that both players have the same discount rates, although in reality it is very likely that different banks and different lenders have different opportunity costs. The haircut proposed by the company in the reorganization plan is denoted by h, and the liquidation recovery ratio is α. The extensive form game is displayed in Figure 2, where senior bank creditors’ payoff is in the first line and the payoff of junior bank creditors is represented on the second line. A normal form game is displayed in Figure 3. There are only two possible votes or moves: reorganization or liquidation, henceforth R and L, respectively.

The conditions for Junior to play R are the following:

I: ℎ < [𝛼(𝑝 − 𝜎𝑝 − 1 + 𝜎) + 1 + 𝑝(𝜎 − 1)]/[𝑝(𝜎 − 1) + 1] II: ℎ < [𝑝(1 − 𝛼 − 𝜎 + 𝛼𝜎) − 𝛼𝜎]/[𝑝(1 − 𝜎)]

Based on these conditions, Senior knows what the best response of Junior is and decides its action by backward induction. The equations displayed above require some interpretation to define our empirical strategy. According to our model, the players will place much less weight on distributive questions or on the total amount of debt. What matters is the probability of a judge approving the plan (in case no agreement is reached), the liquidation recovery ratio and the discount rate.

Condition 1 demonstrates that junior players are likely to accept any haircut when their discount rates are high (as when 𝜎 = 1, h < 1). On the other hand, when they

17

are patient enough, Junior faces a tradeoff between the haircut and the liquidation value (as when 𝜎 = 0, h < 1- 𝛼). Condition 2 continues in the same way.

To define possible Nash equilibriums, we use parameters based in our data (the next section contains detailed analysis of our sample). The average haircut is 43%, and senior bank creditors represent 20% of total debt. For purposes of simplicity, we assume that all debt is split between banks, such that junior bank creditors represent 80% of total debt. We assume that total debt is 100. The average liquidation recovery rate in our sample is 1.5, which means that in case of liquidation, an asset sale would yield a total of 150 to be split among creditors. Our in-sample probability that a judge will approve a plan is 12%. As a baseline scenario, we assume that players have a discount rate of 5%.

Based on these parameters, the only Nash equilibrium is (Liquidation, Liquidation) because R is always a dominated strategy. As we previously demonstrated, changes in the haircut or in the percentage of senior bank debt do not result in any equilibrium change. Using ceteris paribus analysis, we identify three situations in which (Reorganization, Reorganization) would be the Nash equilibrium. First, the probability of a judge approving a plan would have to be higher than 97%, which means that players must be sure the judge will approve a reorganization to vote for it. If such was the case, two Nash equilibriums would exist: both (Liquidation, Liquidation) and (Reorganization, Reorganization). The second possibility would be a discount rate higher than 60%, such that players would have to be overly risk averse and discount future outcomes at an extremely high rate. The third option would involve liquidation recovery rates less than 60%; in other words, an asset sale would have to yield less than 60% of the total debt amount for players to vote in favor of reorganization. Figure 3a depicts our baseline scenario, whereas Figure 3b shows these three possibilities in which (R, R) can be Nash equilibrium.

Despite these initial insights, there may be other factors affecting decision-making other than those captured by our theoretical model, as the average approval rate in our sample is 78%, implying that bank creditors vote in favor of reorganization at a

18

much higher frequency than our model indicates. Thus, we arrive at our data analysis and our empirical strategy.

4. DATA ANALYSIS

Our main sources of data are corporate reorganization filings, judicial trustees’ websites and files from one of the main Brazilian courts (Vara de Falências e

Recuperação Judicial de São Paulo). We have data on 125 corporate

reorganizations in Brazil from 2006 to 2016. For each case, we analyze the following documents: list of creditors, creditors’ meeting minutes, corporate reorganization plans and modified plans, and reports of the valuation of assets.

The entire process in Brazil from registration to approval or rejection can take up to two years, which is the reason that some cases might be missing in our dataset: some large reorganization plans, such as Grupo Oi, the largest reorganization case in Brazil to date, have not been voted on yet. Our initial sample had more than 140 cases, but because of missing information, we discarded 15 of them.

Although the amount of reorganization filings in Brazil is much higher than the number in our sample, Brazil lacks data centralization. Some documents can be found at state courts, and filing companies and consulting firms often do not provide such documents on their websites. Despite this challenge, our sample contains reorganization filings from 10 different states but contains a heavier weight of south and southeast regions (41% of the companies are from São Paulo, the biggest Brazilian state in economic terms, 19% are from Rio Grande do Sul, 13% are from Santa Catarina and 11% are from Goiânia).

For the cases in which the proposed conditions were different for different banks, we noted in our files the highest bank haircut as well as the longest waiting period. In cases of foreign debt in US dollars, we used the exchange rate for the month of the approval or rejection of the plan to convert the figures to Brazilian Reais.

19

For each case, we gathered the following information for both the secured and unsecured classes: readjustment index, interest rate, proposed haircut, and amortization and waiting period. Because our interest lies in the financial institutions, we detailed each bank’s credits and behavior during the creditors’ meetings. In this sense, we typified bank behavior through 10 different possible interventions, which can be found in Table 1. To include the dimensions of the company’s size and its financial health, we collected data on the valuation of the companies’ assets as reported in the reorganization plans and estimated by the consulting companies that prepared the legal documents because our database lacks information on balance sheet figures.

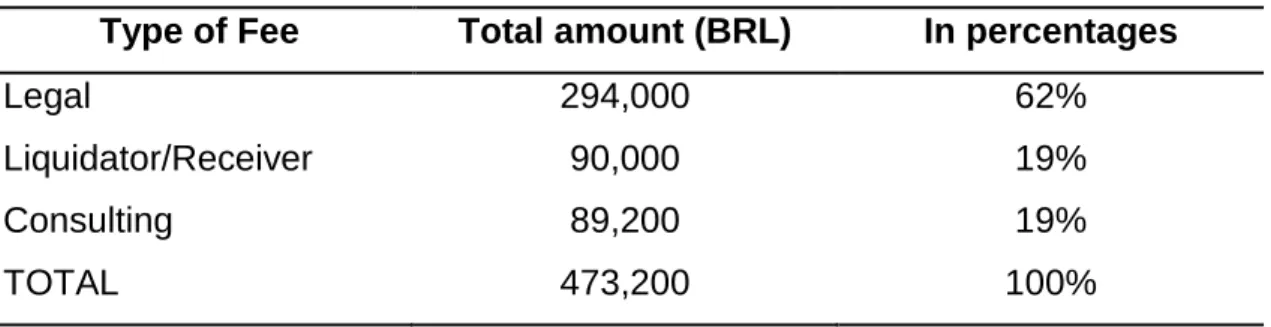

The costs of the entire reorganization process in Brazil are approximately R$500 thousand (approximately US$170 thousand), which is equivalent to 20% of the companies’ projected administrative expenses for the whole period. The companies’ names are omitted, and the details are shown in Table 2.

For the entire sample, each bank acted as a creditor in an average of five bankruptcy procedures. If we consider only the six largest banks in Brazil (Banco do Brasil, Bradesco, Caixa Econômica Federal, HSBC, Itaú and Santander), this number increases to 52. To account for this difference, a dummy for large banks is included in our regression models.

The average age of the companies is 31 years. Companies with approved reorganization plans have an average age of 33 years, while those with rejected plans have an average age of 30 years, which represents only a slight difference. Nevertheless, we include this variable as a control in our regression model.

Of all of the cases included in our sample, we were able to collect information on asset value for 58 companies. The average market value of the companies is R$160 million, and the average asset coverage ratio is 1.4, which means that in a case where the company is liquidated, the sale of the evaluated assets accounts for 104% of the company’s total debt.

20

The reorganization approval rate for our sample is 78%, which is comparable to the 75% rate for Canada demonstrated by Fisher and Martel (1995), although the authors’ data refer to the 1980s. Despite the high approval rate, only one in four companies survives the reorganization process in Brazil. In the United States, this proportion falls to only one in eight.3

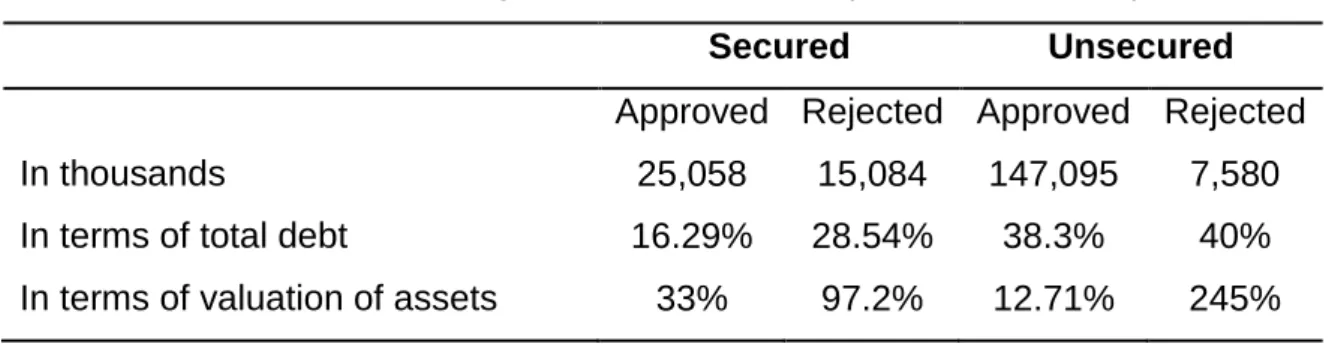

Table 3 contains detailed information on the conditions offered to the banks, both as secured and unsecured creditors, in cases of haircuts or debt re-profiling. The approved plans required a larger haircut for secured creditors than the plans that were not approved (43% versus 39%), while the contrary holds for unsecured creditors (42% versus 52%). On average, the required waiting and amortization periods were longer for the approved plans, regardless of creditor class. The fact that the average haircut is similar for both classes of creditors is contrary to international evidence demonstrating that secured creditors fare relatively well in formal bankruptcies in countries such as the United States or the United Kingdom (Franks and Sussman (2005), Davydenko and Franks (2006)).

Banks carried average secured debt of approximately R$14 million and unsecured debt of approximately R$98 million. Large banks had unsecured debt in 86% of our cases and secured debt in 40% of the cases, with an average value of R$12.8 million and R$3.48 million, respectively. However, if we exclude HSBC, average unsecured debt becomes R$4 million. Contrary to our expectations, in only 5% of the cases is the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) the creditor, with an average amount of R$37.8 million.

On average, bank debt represents 44% of the companies’ total debt. Table 4 presents statistics for the average amount of bank debt for each creditor class. For both approved and rejected cases, the proportion of unsecured debt to companies’ total debt was higher than the proportion of secured debt. Additionally, rejected cases had more secured debt than the approved cases (28.54% versus 16.29%). These findings suggest that the presence of secured debt creates challenges for the approval of the plan due to the negotiating power of the secured banks, which usually apply pressure for better conditions (large banks made two-thirds of the requests for

21

better debt terms). Finally, Table 5 presents information regarding the frequency of certain events during the reorganization process. Sales of productive units to repay debt occurred 23% of the time, which indicates the use of merger and acquisition activities after reorganization approval. Gilson, Hotchkiss and Osborn (2015) argue that the use of M&A activities during bankruptcy proceedings blurs the traditional distinctions between reorganization and liquidation. Debt conversion occurred in only 6% of the sample.

To contrast our findings with those of Brunner and Kahnen (2008), we also compare the number of banks involved in a certain case and the plan approval rate. Our sample contains 108 banks. On average, each bank was involved in 5 reorganization cases. However, large banks were involved in 52 cases. The correlation between the number of junior banks involved and the approval rate is minus seventeen percent (-17%). For senior banks, the number is similar, at minus fourteen percent (-14%). This result accords with Brunner and Kahnen’s (2008) findings: the more banks that are involved in a reorganization case, the more likely the reorganization is to be rejected by the creditors. The average number of banks creditors is slightly larger for cases involving conflict (8 versus 5). Banco do Brasil and Itau (two of the six largest banks in Brazil) are creditors in 80% of the conflict cases, while they were creditors in only 57% of the total cases for the entire sample. Bank creditors requested that guarantees should be maintained 14% of the time, while we verify only half of this frequency for the entire sample, as mentioned in page 18.

Our first analysis regarding bank behavior consists of analyzing requests from bank creditors. The most frequent interventions were the bank requesting different payment conditions (7.8%), the bank requesting the maintenance of guarantees (7%) and bank disagreement with the listed credit or presenting a challenge (3%). All of the other interventions had a frequency of 1% or less. Large banks made two-thirds of these requests, which may indicate their negotiating power.

To better understand the banks’ power empirically, we calculated a debt concentration index (DCI), which is similar to the Herfindahl index. The Herfindahl index goes from zero to one and is traditionally used to assess the amount of

22

competition among firms in a certain industry. Higher values indicate more monopolistic markets. Here, we use it as a measure of the competition between banks during a certain reorganization case. The formula is:

𝐷𝐶𝐼 = ∑ 𝑠𝑖2 𝑛

𝑖=1

For each reorganization process, si measures the proportion of the total debt held by

each bank involved in the negotiation. We do so because some authors argue that debt dispersion can often lead to coordination failures (Franks and Sussman (2005), Bolton and Scharfstein (1996)). As expected, the average DCI for secured debt is 0.7, while that for unsecured debt is 0.45. Because senior debt is more concentrated than unsecured debt in practice, this result suggests that senior bank creditors are able to agree to terms more easily than unsecured bank creditors can. In fact, the correlation between the average debt concentration and the plan approval rate is minus thirteen percent (-13%).

Our second analysis of bank behavior consists of observing cases in which a conflict existed between the unsecured and secured bank creditors, which represents 16% of the sample, or 20 cases. While the average approval rate for the entire sample is 74%, for cases in which the secured and unsecured lenders disagree, this value falls to 12%, which suggests an in-sample probability of a judge approving the plan of 12%.

Ayotte (2009) argues that when senior creditors are oversecured, i.e., when their claims are worth less than the value of the firm’s assets, cases are more likely to result in liquidation, while the opposite holds when they are undersecured. In these cases, “creditor conflict is likely to be most pronounced.” To see if this holds for our cases, we calculate the senior bank debt to asset valuation ratio, which averages 0.88 for the entire sample. Using a total senior debt/asset valuation ratio, the average value is 1.93, which indicates that senior creditors are undersecured. This result is in line with Ayotte’s argument, as our average reorganization approval ratio is 78%.

23

However, conflict occurs only 16% of the time. For those cases in which there is conflict, these averages are 0.61 and 0.74, respectively.

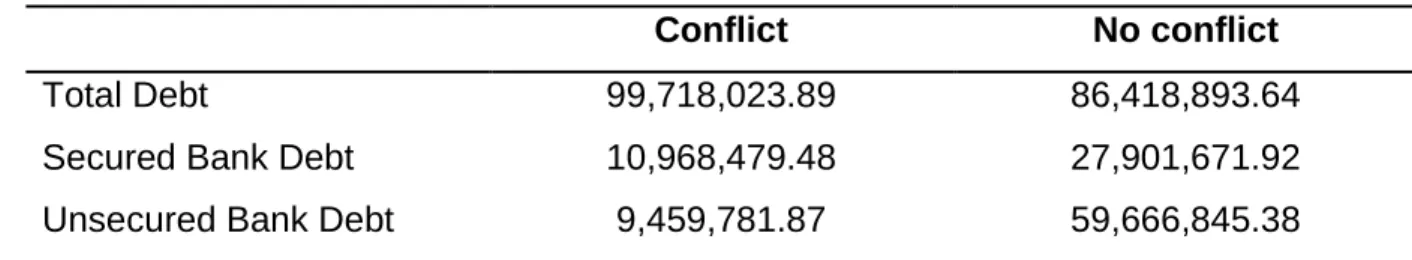

Table 6 contains detailed information about debt and bank debt in Brazilian Reais. Contrary to our expectations, the total amount of both secured and unsecured bank debt is larger in the no conflict cases. In the conflict cases, bank debt represented a much lower percentage of the total debt when compared to the no conflict cases (20% versus almost 100%). Another finding that drew our attention was that the total asset valuation for the conflict cases was, on average, 19 times higher than that for the no conflict cases.

Regarding haircuts, senior creditors had an average haircut of 41% in conflict cases, whereas for junior bank creditors, the haircut was 49%. The average haircut for the entire sample is 43%, which suggests that conflict is associated with a greater haircut for junior creditors. The senior-to-junior ratio, which is the total amount of secured debt divided by the total amount of unsecured debt, was 4.1x for the entire sample and 1.0x for the conflict cases. This result means that, on average, when there was a conflict, the amount of unsecured debt was the same as secured debt.

Table 7 provides information on the plan conditions and conflicts between the creditor classes. Although the haircut level is the same for senior creditors in all cases, unsecured bank creditors receive, on average, a higher haircut in conflict cases. Nevertheless, the amortization and waiting periods are shorter when there is a conflict. This mixed evidence does not make it possible for us to conclude that senior creditors have come to dominate the Chapter 11 process, as Ayotte (2009) demonstrates. Overall, the evidence on conflict cases is mixed, which reinforces the use of a dummy for conflict cases in our empirical model.

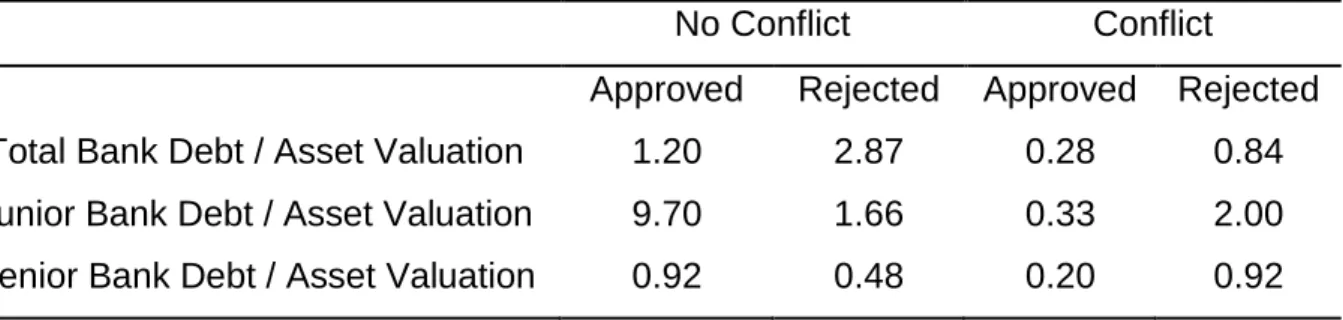

Baird and Morrison (2001) also provide a useful framework to understand conflict. They model the shutdown decision as a real option. We combine their ideas with Ayotte’s in Table 8 to see if this approach yields additional insights. Indeed, we verify that for those cases when there is a conflict, senior bank creditors were in the money, as their claims represented less than 100% of the company’s market valuation. This

24

means they could simply exercise their option and liquidate the firm. In the cases were there was no conflict, however, both creditor classes were out of the money, with junior bank creditors being deep out of the money.

If we sub-divide columns for approval or rejection (Table 9), we verify that in the cases when conflict existed and plans were approved, both creditor classes were deep in the money, which justifies the struggle. Actually, these are the only cases where junior bank creditors are in the money. When plans were approved but there was no conflict, on the other hand, junior banks were so out of the money that a conflict did not seem justifiable, as their expectation of recovery was minimal. These evidence support Branch and Ray (2007)’s idea that subordinate creditors can have considerable leverage in a reorganization process.

5. EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

In this section, our objective is to understand what factors influence a bank creditor’s vote during creditors’ meetings using pooled cross-sectional data. We follow the regression proposed by Fisher and Martel (1995) with some adaptation4. Our dependent variable is the vote of a bank creditor. It consists of a dummy variable that assumes the value of one if the bank creditor is in favor of reorganization and zero otherwise.

We use several control variables because certain aspects are not captured by the proposed theoretical game due to the absence of relevant parameters or environmental differences. We include year controls (not displayed in the equation below) to account for structural changes that might affect the vote of a bank creditor and that are common to all of the companies, e.g., economic conditions. We also control for large banks because these institutions may behave differently than other bank creditors (for example, they can spend larger amounts of money to hire the best law firms). We define a player’s reorganization payoff as 1 minus the proposed haircut for its class. The liquidation payoff measures how much of the total debt that an asset sale can pay off.

25

In this sense, we run the regression below, where i denotes a bank creditor and j denotes a certain firm.

𝑉𝑜𝑡𝑒𝑖,𝑗= 𝛼0 + 𝛼1𝑅𝑒𝑜𝑟𝑔𝑃𝑎𝑦𝑜𝑓𝑓𝑆𝑒𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟𝑖,𝑗+ 𝛼2𝑅𝑒𝑜𝑟𝑔𝑃𝑎𝑦𝑜𝑓𝑓𝐽𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟𝑖,𝑗

+ 𝛼3𝐿𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑑𝑃𝑎𝑦𝑜𝑓𝑓𝑖,𝑗+ 𝛼4𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑃𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑟𝑖,𝑗+ 𝛼5𝐴𝑔𝑒𝑗 + 𝛼6𝐿𝑎𝑟𝑔𝑒𝐵𝑎𝑛𝑘𝑖 + 𝛼7𝐽𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟𝑖 + 𝛼8%𝑆𝑒𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟𝐷𝑒𝑏𝑡𝑗+ 𝛼9𝑉𝑜𝑡𝑒𝐽𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟 ∗ 𝑅𝑒𝑜𝑟𝑔𝑃𝑎𝑦𝑜𝑓𝑓𝐽𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑜𝑟

The robust regression results are presented in Table 10. Wer un both OLS and logit regressions. Model (3) is our standard for interpretation, as it contains both the year controls and interactions. The mere fact that a bank is a junior creditor does not explain the behavioral differences. Moreover, the more power a bank has, the less it will favor reorganization. While Helwege and Packer (2003) report that the probability of liquidation is higher for firms affiliated with banks from large industrial groups (keiretsus) in Japan, our results show that large banks do not have any intrinsic characteristic that makes them behave differently from any other bank creditor. We also include the number of banks involved in each negotiation (results not reported) in order to compare our results with Brunner and Kahnen (2008). Surprisingly, this variable is not significant to explain the vote of a bank creditor in any of the estimates.

In accordance with our theoretical model, the proportion of secured debt does not seem to be relevant in explaining a bank creditor’s vote. This result is contrary to the findings of Fisher and Martel (1995) that plans with higher ratios of secured debt are more likely to be accepted. This result might indicate that senior banks do not have insider knowledge about the financial viability of the firm. Moreover, the payoff of junior creditors is significant in explaining a bank creditor’s vote in all of the regressions. However, the liquidation ratio does not seem to play much of a role in decision-making, as our theoretical model proposes.

In general, the results are mixed and suggest three things: first, the haircut proposed by the company, rather than firm size or age, is the main factor driving bank creditors’ decisions, which differs from the traditional literature (Hotchkiss, 1993). Second, the proportion of senior debt is irrelevant in explaining bank responses to

26

reorganizations. Moreover, the findings from our data analysis demonstrate that coordination failures signal negotiation problems and often lead to liquidation.

While Branch and Ray (2007) argue that subordinate debtholders have considerable leverage in the bankruptcy negotiation process, Ayotte (2009) states that senior creditors have come to dominate the Chapter 11 process. Our evidence on the irrelevance of the proportion of senior debt in explaining creditor votes is more in line with the former study.

To account for confounding effects that might explain our results, we compare our sample with the 1000 largest Brazilian companies for the same period (statistics not reported). Although our study lacks balance sheet information, some back-of-the-envelope calculations using our asset valuation measure demonstrate that the companies in our sample are 10 times smaller than these 1000 companies. Hence, because our sample companies might differ from the average company, our results may deviate from most of the international evidence. To improve on this limitation, further research should include as much balance sheet information as can be obtained. In addition, an analysis of post-reorganization performance would provide a measure of the efficiency of the Brazilian bankruptcy code.

Moreover, the literature suggests that firms with poor operating performance usually prefer reorganization, as Chapter 11 functions as a screening device (Mooradian, 1994). Thus, there may be some self-selection bias in our data. In this sense, it is important to mention that our results do not imply any causality. Our goal was to identify associations between variables, as our sampling method can lead to some endogeneity biases. Although it is impossible to correct for such bias, it would only bias the estimates toward zero, thus underestimating some of the associations.

27 6. CONCLUSION

The goal of this study was to analyze how bank creditors vote on corporate reorganization filings. The literature presents mixed findings on whether senior creditors have come to dominate the negotiation process to accept or decline reorganization. We use pooled cross-sectional data from 125 reorganization filings in Brazil from 2006 to 2016. Our data demonstrate that senior creditors have less power than initially assumed, as the proportion of senior debt is not associated with favorable votes. This result accords with our proposed theoretical model that players will place much less weight on distributive questions or on the total amount of debt. We also provide insights regarding the effects of conflict between bank creditor classes on the outcome of bankruptcy negotiations, a topic that has yet to be addressed in the empirical bankruptcy literature so far. If we look at the bargain as the exercise of a real option, it is clear that conflict exists when senior bank creditors are in the money but the opposite holds for junior bank creditors. Despite mixed evidence, we demonstrate that conflict is closely linked to banks voting in favor of liquidation, regardless of creditor class. To deepen our analysis, future research should include balance sheet information and data on post-reorganization performance.

7. REFERENCES

ALLEN, F., CHUI, M., MADDALONI, A. (2008) Financial Structure and Corporate Governance in Europe, the USA, and Asia.” Handbook of European Financial Markets and Institutions, 10, 31-67

ANNABI, A., BRETON, M., FRANÇOIS, P. (2010) Resolution of Financial Distress under Chapter 11. Working Paper 10-48 Centre Interuniversitaire sur le Risque, les Politiques EÉconomiques et l’Emploi

ASQUITH, P., GERTNER, R., SCHARFSTEIN, D. (1994) Anatomy of Financial Distress: An Examination of Junk Bond Issuers. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 109, 625-658

AYOTTE, M. (2009) Creditor Control and Conflict in Chapter 11. Journal of Legal Analysis, 1(2)

28

BAIRD, D.G., (2001) MORRISON, E.R. Bankruptcy Decision Making. John M. Olin Law & Economics Working Paper, 126 (2)

BEBCHUK, L.A., CHANG, H.F. (1992) Bargaining and the Division of Value in Corporate Reorganization. Journal of Law, Economics & Organization, 8(2), 253-279 BERGMAN, Y.Z., CALLEN, J.L (1991) Opportunistic Underinvestment in Debt Renegotiation and Capital Structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 29, 137-171. BOLTON, P., SCHARFSTEIN, D. (1996) Optimal debt structure and the number of creditors. Journal of Political Economics, 104, 1-25

BRANCH, B., RAY, H. Bankruptcy Investing: How to profit from distressed companies. Beard Books, 2007.

BRUNNER, A., KRAHNEN, J.P. (2008) Multiple Lenders and Corporate Distress: Evidence on Debt Restructuring. The Review of Economic Studies, 75, 415-442. BULOW, J.I., SHOVEN, J.B. (1978) The Bankruptcy Decision. The Bell Journal of Economics, 437-456

CHEN, Y., WESTON, J.F., ALTMAN, E.I (1995) Financial Distress and Restructuring Models. Financial Management, 2 (Summer), 57-75

FAMA, E.F. (1985) What’s different about banks? Journal of Monetary Economics, 15, 29-39

FISHER, T.C.G, MARTEL, J. (1995) The Creditors’ Financial Reorganization Decision: New Evidence from Canadian Data. Journal of law, Economics & Organization, 11(1), 112-126

FRANKS, J., SUSSMAN, O. (2005) Financial Distress and Bank Restructuring of Small to Medium Size UK Companies. Review of Finance, 9, 65-96

GERTNER, R., SCHARFSTEIN, D. (1991) A Theory of Reorganizations and the Effects of Reorganization Law. The Journal of Finance, 46(4), 1189-1222

GILSON, S. C., VETSUYPENS, M.R. (1994) Creditor Control in Financially Distressed Firms: Empirical Evidence. Washington University Law Review, 72(3), 1005-1025

GILSON, S. C., HOTCHKISS, E., OSBORN, M. (2015) Cashing out: the Rise of M&A in Bankruptcy. Harvard Business School Working Paper 15-057

HOTCHKISS, E. S. (1993) Investment Decisions under Chapter 11 bankruptcy, Doctoral dissertation, New York University

HOTCHKISS, E.S., JOHN, K., MOORADIAN, R.M., THORBURN, K.S. (2008) Bankruptcy and the resolution of financial distress. Handbook of Empirical Corporate Finance, Chapter 14, 2

29

JAMES, C. (1995) When do Banks Take Equity in Debt Restructurings? The Review of Financial Studies, 8 (4), 1209-1234

JACKSON, T.H. (1982) Bankruptcy, Non-Bankruptcy Entitlements, and the Creditors’ Bargain. The Yale Law Journal, 91(5), 857-907

KIRSCHBAUM, D. (2009) A recuperação judicial no Brasil: Governança, Financiamento Extraconcursal e Votação do Plano. [PhD Thesis] Universidade de São Paulo. Faculdade de Direito

MOORADIAN, R.M. (1994) The Effect of Bankruptcy Protection on Investment: Chapter 11 as a Screening Device”. Journal of Finance,, 49, 1403-1430

RAJAN, R. (1992) Insiders and Outsiders: The Choice Between Informed and Arm’s-Length Debt. Journal of Finance, 47, 1367-1400.

SILVA, V.A.B., SAITO, R., MANOEL, P.M.B.F. (2015) Determinants of Delay in Corporate Reorganizations [PhD Thesis] Fundação Getulio Vargas. Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo

Serasa Experian – Indicador Seraxa Experian de Falências e Recuperações.

[Access in Sep,20th, 2016] From

https://www.serasaexperian.com.br/release/indicadores/falencias_concordatas.htm WELCH, I. (1997) A Theory of Asymmetry and Claim Priority Based on Influence Costs. The Review of Financial Studies, 10(4), 1203-1236

WHITE, M.J. (1981) Economics of bankruptcy: Liquidation and reorganization. Working paper series / Salomon Brothers Center for the Study of Financial Institutions

30 8. TABLES, LISTS AND FIGURES

List 1: Reorganization tools available to companies according to Brazilian Law I: Debt Re-profiling: new terms and conditions;

II: Spin-off, merger, consolidation or transformation of a company, opening of a wholly-owned subsidiary, or quota or share assignment, with due regard of partners;

III: Change in corporate control; IV: Changes to management team;

V: Creditors have voting rights separate from managers; VI: Share capital increase;

VII: Transfer of a commercial or industrial business, including the right to lease;

VIII: Reduction in salaries, offsetting of working hours and workday reduction, by collective agreement or convention;

IX: Debt novation;

X: Incorporation of a society of creditors; XI: Partial sale of assets;

XII: Equalization of financial charges, with the initial date as the date of the reorganization request;

XIII: Enjoyment of the company (“usofruto”); XIV: Shared management;

31

Table 1: Bank behavior – bank intervention during creditors’ meetings

Code Bank Intervention

0 No Intervention / Bank did not hand in required documents on time / Bank arrived late to the Committee / Bank was absent

1 Bank did not agree with listed credit or credit classification or presented a Challenge Procedure. In Portuguese, this is called Impugnação de

Crédito

2 Bank requested longer period for analysis or requested Meeting Suspension

3 Bank requested conditions other than those presented by the company or presented an Alternative Plan

4 Bank assigned receivables to a Receivables Investment Fund

5 Bank requested that guarantees not be suspended or that it will maintain execution against guarantors or co-obligors, as a creditor is defined as a person or entity who promises to pay back a loan if the original borrower does not pay it back, and a co-obligor is defined as one who is bound together with one or more others to fulfill an obligation

6 Unsecured Bank did not agree with conditions proposed to Secured Banks or vice-versa

7 Bank did not agree with Reorganization request or stated that proposed Plan lacks legal certainty

8 Bank stated that it has Priority Credit. In Portuguese, this is called

Crédito Extraconcursal

9 Bank did not agree with conditions proposed to Banks in the same group

33

Figure 1: Reorganization Requests versus Economic Conditions

34

Figure 2: Creditors’ bargain: Extensive form game

Pa ra m e te rs • H a ircu t = h • % Se n io r D e b t = β • % Ju n io r D e b t = (1 -β ) • D isco u n t R a te = σ • T o ta l D e b t = D • L iq u id a ti o n re co ve ry = α β (1 -σ )(1 -h )D (1 -β ) (1 -σ )(1 -h )D

Se

n

io

r

Ju

n

io

r

R eo rg an iz at io n Liqu idat ion Re or ga niz at ion Liquid ation Re or ga niz at ion Liquid ation Re or ga niz at ion Liquid ation Re or ga niz at ion Liquid ationJu

d

ge

β (1 -h )D (1 -β )(1 -h )D β α D (1 -β )α D β (1 -σ ) α D (1 -β )(1 -σ ) α D β (1 -σ )(1 -h )D (1 -β ) (1 -σ )(1 -h )D β (1 -σ ) α D (1 -β )(1 -σ ) α D35

Figure 3: Creditors’ bargain: Normal form game

Figure 3a: Creditors’ bargain: Baseline scenario – Normal form game

Figure 3b: Creditors’ bargain: Three cases when Reorganization is Nash equilibrium

Order of players and strategies follow figures 3 and 3a. Nash equilibriums are highlighted in gray.

β(1-h)D ; (1-β)(1-h)D p[β(1-σ)(1-h)D]+(1-p)[β(1-σ)αD ; p[(1-β)(1-σ)(1-h)D]+ (1-p)[(1-β)(1-σ)αD] p[β(1-σ)(1-h)D]+(1-p)[β(1-σ)αD ; p[(1-β)(1-σ)(1-h)D]+ (1-p)[(1-β)(1-σ)αD] βαD ; (1-β)αD

R

L

R

L

Senior

Junior

11 ; 45 26 ; 105 26 ; 105 30 ; 120R

L

R

L

Senior

Junior

Nash equilibrium11.4 ; 45.6

11.3 ; 45.4

11.3 ; 45.4

30 ; 120

11.4 ; 45.6

11.1 ; 44.4

11.1 ; 44.4

30 ; 120

11.4 ; 45.6

11.3 ; 45.3

11.3 ; 45.3

12 ; 48

Case 1: p = 97%

Case 2: σ = 60%

Case 3: α = 60%

36

Table 2: Administrative expenses in a reorganization process – estimated for a 7-year period (in 2012 Brazilian Reais)

Type of Fee Total amount (BRL) In percentages

Legal 294,000 62%

Liquidator/Receiver 90,000 19%

Consulting 89,200 19%

TOTAL 473,200 100%

Table 3: Average reorganization conditions: secured and unsecured bank creditors

Secured Unsecured

Approved Rejected Approved Rejected

Haircut 45% 35% 46% 47% Re-profiling Index TR1 TR TR TR Interest Rate2 4% 4% 4% 4% Amortization3 103 91 111 104 Waiting Period3 20 17 19 17 1TR “Taxa Referencial”; 2

37

Table 4: Average bank debt amount (in Brazilian Reais)

Secured Unsecured

Approved Rejected Approved Rejected

In thousands 25,058 15,084 147,095 7,580

In terms of total debt 16.29% 28.54% 38.3% 40%

In terms of valuation of assets 33% 97.2% 12.71% 245%

Table 5: Frequency of events during reorganizations

Event Frequency

Capital Subscription, Raising Capital or Spin-Off 13%

Debt Conversion 6%

Debt Issue 5%

Share Buyback 1%

Productive Unit Sale 23%

Creditor as a Special Partner* 19%

*By Special Partner, we mean creditors who agree to better conditions for debt payment and/or offer new lines of credit.

38

Table 6: Average debt amount and conflict between creditor classes

Conflict No conflict

Total Debt 99,718,023.89 86,418,893.64

Secured Bank Debt 10,968,479.48 27,901,671.92

Unsecured Bank Debt 9,459,781.87 59,666,845.38

Table 7: Average conditions and conflict between creditor classes

Conflict No Conflict

Secured Unsecured Secured Unsecured

Haircut (%) 41% 50% 42% 43%

Amortization Period (months) 91 97 107 113

39

Table 8: Reorganization as the exercise of a real option

No Conflict Conflict

Approval Rate 85% 12%

Total Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 9.55 1.89

Junior Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 9.29 1.27

Senior Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 1.03 0.61

Table 9: Reorganization as the exercise of a real option and plan approval

No Conflict Conflict

Approved Rejected Approved Rejected Total Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 1.20 2.87 0.28 0.84 Junior Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 9.70 1.66 0.33 2.00 Senior Bank Debt / Asset Valuation 0.92 0.48 0.20 0.92

40 Table 10: Regression results

The symbols ***, ** and * denote significance at the 1% level, 5% level and 10% level, respectively. Reorg_payoff_senior and Reorg_payoff_junior denote the payoffs of senior and junior bank creditors in the case of reorganization (defined as 1 minus the proposed haircut for their class). Liquid_payoff denotes the payoff a bank creditor receives in case of liquidation. BankPower denotes the percentage of total bank debt a certain bank creditor has. LargeBank_Dummy assumes a value of 1 if the creditor is one of the six largest banks in Brazil, whereas Dummy_Junior assumes a value of 1 if the creditor is unsecured and is zero otherwise. Age represents company age. Vote_junior denotes the vote of unsecured bank creditors. Finally, SeniorDebtRatio represents the ratio of senior debt to total debt.

(1 ) (2 ) (3 ) (4 ) (5 ) V AR IABL ES OL S OL S OL S L OG IT L OG IT R e o rg _ p a yo ff _ se n io r -0 .5 8 3 * -1 .0 1 6 ** * -0 .0 2 4 7 -3 .1 1 9 * -5 .0 5 5 ** * (0 .2 9 5 ) (0 .3 5 0 ) (0 .0 8 0 7 ) (1 .6 4 2 ) (1 .7 9 0 ) R e o rg _ p a yo ff _ ju n io r 1 .2 7 2 ** 1 .1 5 6 * -1 .3 9 4 ** * 6 .8 1 7 ** * 6 .7 4 9 * (0 .4 8 8 ) (0 .5 9 0 ) (0 .1 8 3 ) (2 .4 0 6 ) (3 .8 0 1 ) L iq u id _ p a yo ff -0 .0 6 3 7 -0 .0 0 8 7 5 0 .0 1 0 2 -0 .4 4 7 1 .0 4 3 (0 .0 6 2 3 ) (0 .1 4 6 ) (0 .0 4 2 4 ) (0 .3 9 4 ) (1 .3 2 9 ) Ba n kP o w e r 0 .0 0 2 4 1 0 .0 1 4 2 -0 .1 4 6 ** * 0 .0 0 9 5 7 0 .0 6 4 4 (0 .0 3 5 9 ) (0 .0 3 2 7 ) (0 .0 3 4 3 ) (0 .1 5 0 ) (0 .1 4 3 ) L a rg e Ba n k_ D u mmy -0 .0 9 2 9 -0 .0 8 2 0 -0 .0 0 5 1 8 -0 .5 6 1 -0 .6 4 3 (0 .0 8 8 8 ) (0 .0 8 4 3 ) (0 .0 1 8 9 ) (0 .5 0 7 ) (0 .5 9 7 ) Ag e 0 .0 0 5 9 4 * -0 .0 0 3 8 1 -0 .0 0 0 6 6 5 0 .0 3 7 6 -0 .0 3 3 5 (0 .0 0 3 0 9 ) (0 .0 0 8 2 6 ) (0 .0 0 1 9 6 ) (0 .0 2 3 5 ) (0 .0 5 7 5 ) V o te JP a yJ 1 .6 7 1 ** * (0 .0 7 7 6 ) Se n io rD e b tR a ti o -0 .0 2 0 6 0 .1 9 3 0 .0 5 1 3 -0 .0 7 6 7 1 .4 5 6 (0 .1 8 6 ) (0 .2 5 8 ) (0 .0 6 5 6 ) (1 .0 1 6 ) (1 .4 9 9 ) Ju n io r_ D u mmy -0 .0 1 2 1 0 .0 8 9 5 -0 .0 6 1 6 0 .6 7 7 (0 .0 9 4 4 ) (0 .1 0 3 ) (0 .5 2 7 ) (0 .6 9 8 ) C o n st a n t 0 .3 2 1 0 .4 0 9 0 .8 3 0 ** * -1 .0 8 8 -2 .3 7 1 (0 .2 7 2 ) (0 .4 0 6 ) (0 .2 3 2 ) (1 .3 3 3 ) (6 .0 5 5 ) Y e a r co n tro ls No Ye s Ye s No Ye s O b se rva ti o n s 11 4 11 0 70 11 4 81 R -sq u a re d 0 .1 0 6 0 .2 8 9 0 .9 7 7 R o b u st st a n d a rd e rro rs in p a re n th e se s ** * p <0 .0 1 , ** p <0 .0 5 , * p <0 .1

41 9. NOTES

1

This information was provided by Deneszzuk e Antonio Sociedade de Advogados and can be found at http://dasa.adv.br/recuperacao-judicial/.

2According to Jackson (1982), “A more profitable line of pursuit might be to view

bankruptcy as a system designed to mirror the agreement one would expect the creditors to form among themselves were they able to negotiate such an agreement from an ex ante position.”

3

http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/mercado/2016/10/1820669-so-uma-em-cada-quatro-empresas-sobrevive-apos-recuperacao-judicial.shtml; Branch and Ray (2007).

4

Using a sample of 338 financial reorganization plans in Canada, they find evidence that plans with high ratios of secured debt are more likely to be accepted, which they interpret as evidence of the secured creditors having insider information about the financial viability of the firms.