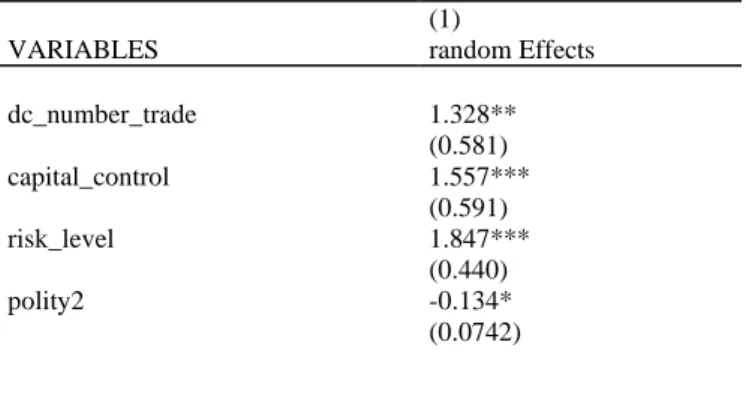

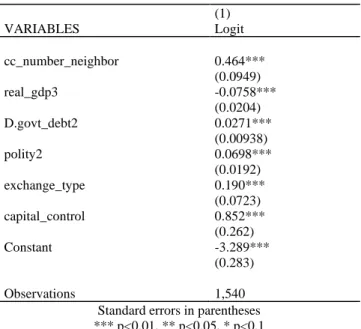

Contagion of financial crises across neighbors and trade partners

Texto

Imagem

Documentos relacionados

Durante vários anos foram estudados certos padrões comportamentais com possível risco para o desenvolvimento de ITUs recorrentes, tais como micção pré e pós-coital, frequência

Tiver profissionais adequados e competentes Tiver profissionais competentes llll Tiver profissionais adequados e competentes Tiver bons funcionários ll Tiver

Wilson Henry Irvine, nascido no Nordeste dos EUA no ano de 1869 e falecido na mesma região em 1936, foi um mestre do paisagismo no Impressionismo americano

França e do “que poderíamos chamar a sua escola” sobre o caso do surrealismo português, mas também a tripartição do modernismo português “…considerando que, tal

Acerca do surgimento do direito fundamental à vida privada: Pode-se dizer que ele somente veio a ser apercebido como uma das projeções da dignidade da pessoa humana quando

Com este trabalho pretendeu-se caracterizar a população com alta hospi- talar na região de Lisboa e Vale do Tejo entre 2009 e 2011, com mais de 1 dia e menos de 365 dias

O presente trabalho objetivou quantificar MLT, trans-RSV, fenólicos totais e a atividade antioxidante (AA) em vinhos monocasta portugueses, bem como averiguar a

A análise do contexto pretende caracterizar o ambiente em que decorreram as atividades ou ações planeadas no projeto de intervenção, dotar os recursos disponíveis e/ou necessários à