Attitudes

and Practices of Pesticide Users

in Saint Lucia, West Indies1

L.

MCDOUGALL,~

L.MAGLOIRE,~

C. J.HOSPEDALES,~

J. E.

TOLLEFSON,

5 M.OOMS,~

N. C.SINGH,~ &

F. M. M.WHITER

This article reports the results of a Saint Lucia survey, part of a larger program, fhaf was the first to document fhe prevalence of suboptimal safety practices among vector confrol and farm workers using pesticides in fhe English-speaking Caribbean. Among ofher things, the survey found that many of 130 pesticide users surveyed were unaware that the skin and eyes were important potenfial routes of absorption. Over a quarter said they had felt ill at some point as a result of pesticide use.

About half the respondents said they had received more than “introducto y” training in safe pesticide use, and most said they always found labels or directions affixed to pesticide containers. However, about half said they never or only sometimes understood the labels, and many of those who said they understood did not always follow the instructions. About a quarter of the smokers said fhey smoked while using pesticides; about a sixth of the survey subjects said fhey ate food while using pesticides; and over 60% said they never wore protective clothing.

T

he

use of chemicals for pest and vec- tor control has led to reductions in the incidence of several key communi- cablediseases,

as well as to major im- provements in food quality and produc- tion. At the same time, however, the toxic nature of these chemicals poses hazards to human health and the environment.Correspondence should be addressed to Dr. C. J. Hospedales, Epidemiologist, CAREC, P.O. Box 164, Port of Spain, Trinidad (tel 809-622-2153). %enior Resident in Community Medicine, Univer-

sity of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada; on assignment to the Caribbean Epidemiology Center. 3Environmental Health Officer, Caribbean Environ-

mental Health Institute (CEHI).

*Head, Surveillance and Field Operations, Carib- bean Epidemiology Center.

5Senior Resident in Community Medicine, Univer- sity of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada; on assignment to the Caribbean Epidemiology Center. 6National Epidemiologist, Ministry of Health, Saint

Lucia.

‘Executive Director, Caribbean Environmental Health Institute (CEHI).

*Director, Caribbean Epidemiology Center.

The potential for occupational expo- sure is of particular concern in the Car- ibbean, where agriculture and vector control programs employ more than 40% of the work force (I). Within Saint Lucia alone, over 1 500 000 kg of pesticides (in- secticides, fungicides, and herbicides) were imported in 1990 (2). Around that time, the approximately 10 000 banana farmers registered with the Saint Lucia Banana Growers’ Association (SLBGA) were thought to use over 75% of these imported pesticides (3). Another 10% or so was being used by public health work- ers in their efforts to control disease vectors, especially the mosquito Aedes

aegypti.

The most frequently used pesticides were organophosphates and carbamates. Both of these two major pesticide classes inhibit the cholinesterase enzyme, per- mitting acetylcholine to accumulate at nerve endings. This leads to excitation followed by paralysis in the parasym- pathetic nervous system (4). Symptoms

of acute poisoning may include dizzi- selected from each of these four districts ness, tremors, blurred vision, headache, (a total of 24 farms). These farms were abdominal cramps, neuropsychologic visited, and all workers available on the abnormalities, and coma. Chronic sub- day of the visit (in a range of l-6) were acute exposures may cause generalized included in the study for a total of 70

weakness (5). such subjects.

MATERIALS

AND METHODS

To help assess and reduce the inci- dence of acute pesticide poisoning and the prevalence of chronic pesticide poi- soning in Trinidad and Tobago and Saint Lucia, a multi-phase project was devel- oped. The project’s first phase consisted of a survey of the knowledge, attitudes, practices, and beliefs (KAPB) of vector control personnel in Saint Lucia and workers on banana farms affiliated with the SLBGA. This article reports the re- sults of that survey. Measurements of cholinesterase levels in the survey sub- jects and in occupationally unexposed controls will be reported elsewhere.

To assist the project, the SLBGA pro- vided a list of the names of its registered banana growers (each of whom owned a farm) classified into eight farming dis- tricts and also by farm size in terms of production (large = over 12 000 lb per week, medium = 2 400-12 000 lb per week, and small = 500-2 400 lb per week). The vast majority of the farms were in the small category.

There were only two large farms on the island, and both were included in the study. Sixty-one subjects (30 from one farm and 31 from the other) were ran- domly selected from the lists of workers on those farms. A random number gen- erator (a scientific calculator) was used for this and other random sampling in the study. There were very few medium farms, so small and medium farms were grouped together, and a stratified ran- dom sample was chosen as follows: First, four of the eight farming districts were randomly selected. Second, six farms were

Of the 23 vector control officers on the island, 20 worked in the North (which has the most tourists); all 20 of these of- ficers participated. The three officers in the South were excluded because they per- formed a wide variety of other duties (e.g., sanitation, public health inspection).

The survey instrument was a modified version of a KAPB questionnaire that had previously been used in Southeast Asia (6, 7). To give this questionnaire a pilot test, it was first administered to 18 farm workers who were not involved in the main survey. The results of this pilot test were used to modify the instrument, after which trained interviewers visited each farm to be surveyed, briefed the selected workers on the general purpose and de- sign of the survey, and administered the questionnaire privately to each subject. These interviewers were four agricultural extension officers who were trained by one of the authors (Magloire) in a one- day workshop to administer the ques- tionnaires in a standardized manner in English (and patois if necessary, many of the workers being more fluent in patois than English). Copies of the modified JSAPB questionnaire employed are avail- able from the authors upon request.

With regard to statistical analysis, Al- pha was set at 0.05 for all tests of signif- icance; categorical data and continuous data were analyzed using the Chi square test and Student’s t-test, respectively.

All individuals who were selected for the study agreed to participate. How- ever, 21 farm workers (17 from the large farms, 4 from the small farms) reported that they were not directly exposed to pesticides, and so their responses were not analyzed. The results presented here

thus reflect the data collected from 130 occupationally exposed people (110 farm workers, 44 from large farms and 66 from small farms, plus 20 vector control per- sonnel) who had mixed or applied pes- ticides. The response rate to each ques- tion varied, however; and so the “number of respondents” cited later in the text cor- responds to the number of individuals who provided coherent answers to each of the specific questions posed.

RESULTS

Demographic

Data

Females accounted for 28 (22%) of the 130 survey subjects. Knowledge, atti- tudes, and practices were not found to vary significantly across genders or be- tween workers on small versus large farms.

Of the 110 agricultural workers on small and large farms, 42 (38%) were farm owners and 68 (62%) were employees. Most of those surveyed (91 of 129 or 71%) had been doing the same job for over five years. Overall, the survey subjects ranged in age from 16 to 75 years, the mean age being 37 and the median age 36. (A lower age limit of 15 years but no upper limit was used in selecting the subjects.)

A total of 128 subjects responded to a question about their education. These re- sponses indicated that 22 (17%) had re- ceived no formal education, 91 (71%) had only attended primary school, and 15 (12%) had received further education at secondary school or institutions of higher learning. Younger individuals were sig- nificantly more likely than their older col- leagues to have obtained some schooling (t = 43.2, p < 0.0001).

Pesticide Procurement and

Handling

Of the 47 individuals who reported being responsible for purchasing pesti-

tides, 43 (92%) obtained them from the Saint Lucia Banana Growers’ Associa- tion, 3 (6%) bought them from local sup- pliers, and 1(2%) ordered them from out- side Saint Lucia.

Most (92 of the 130 survey subjects or 71%) said they prepared and applied pes- ticides, 28 (21%) said they only applied them, and 10 (8%) said they only pre- pared pesticides for application.

A list of the most commonly used pes- ticides (Table 1) was compiled from pes- ticide names (up to six per respondent) provided by the survey subjects. Of 107 farm workers who provided these names, 97 (91%) indicated that they had used cholinesterase inhibitors. Similarly, of the 16 vector control officers who provided pesticide names, 13 (81%) reported using the cholinesterase inhibitor malathion. With regard to exposure frequency, 46 of 106 respondents (43%) said that they used pesticides less than once each week, while the remaining 60 (57%) reported using them at least once a week. Specifically, 21 (20%) reported using them once or twice a week, 16 (15%) three or four times a week, four (4%) five or six times a week, and 19 (18%) every day.

The survey participants were asked where the pesticides they used were stored and whether the storage site was locked. All 20 vector control officers said the pesticides they used were stored at their workplace, and 19 of the 20 (95%) said their stores were locked. The per- centages of agricultural workers provid- ing answers to the two parts of this ques- tion were smalfer. Of the 97 who answered the first part, 71 (73%) reported that the pesticides were stored on the farm; and of the smaller number (66) who re- sponded to the second part, 60 (91%) said that the pesticide stores were fully se- cured. However, of 26 agricultural work- ers who reported that pesticides were stored in their homes, only 13 (50%) in- dicated that the storage site was locked.

Table 1. Names of pesticides that respondent data indicated were most often used. Common names are listed first, followed by registered trade names in parentheses.

Use reported by:

Agricultural Vector control

Pesticide workers (N = 107) officers (N = 16)

Organophosphates and carbamates:

Furadan (Carbofuran) 70 (65%)

Mocap (Ethoprophos) 68 (64%)

Vydate (Oxamyl) 42 (39%)

Primicide (Pirimiphos-ethyl) 41 (38%)

Roundup (Glyphosate) 17 (16%)

Miral (Isazofos) 10 (9%)

Malathion 13 (81%)

Other pesticides: Cramoxone (Paraquat) Fungaflor (Imazalil) TBZ (Thiabendazole) Racumin (Coumatetralyl)

71 (66%) 8 (7%) 5 (5%)

4 (25%)

Beliefs about Health Effects

Almost all the respondents (96% of the 123 who answered) said they had heard of pesticide poisoning; nearly all (98%) agreed that the pesticides they used were poisonous; and most (93%) agreed that some pesticides were more harmful than others.

Many workers overestimated their knowledge of how pesticides gain access to the human body. Of the 100 respon- dents who claimed such knowledge, only 57% (kappa = 0.14) and 64% (kappa = 0.28), respectively, identified the skin and eyes as potential routes of absorption. Knowledge of the nasal and oral routes of inhalation and ingestion was higher, with 89% (kappa = 0.78) and 88% (kappa = 0.76) of the respondents an- swering correctly.

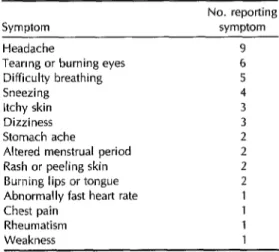

When asked if they had ever felt ill as a result of pesticide use, 36 of 125 sub- jects (29%) said that they had. Their re- ported symptoms are listed in Table 2. While the total number reporting partic- ular symptoms was 42, the total number

46 Bulletin of PAHO 27(l), 1993

of lifetime episodes reported by the sur- vey participants was 114. The likelihood of a worker having been affected was not found to be significantly related to gen- der, farm size, occupation, or having been on the job over five years. However, the average age of the group experiencing symptoms (44 years) was significantly

Table 2. Symptoms attributed by the survey participants to pesticide exposure.

Symptom Headache

Teanng or burning eyes Difficulty breathing Sneezing

Itchy skin Dizziness Stomach ache

Altered menstrual period Rash or peeling skin Burning lips or tongue Abnormally fast heart rate Chest pain

Rheumatism Weakness

No. reporting symptom

higher than the average age of the group Table 3. Training that 122 respondents said

reporting that they had been unaffected they had received in the safe handling of

(34 years, t = 12.9, p < 0.001). aesticides.

In answer to a question about what they would do if they suspected they were ill as a result of pesticide use, 28 of the 70 responding (40%) said they would tell no one or would take their own medi- cine. The other 42 respondents said they would report the illness to someone who could theoretically document such an in- cident: 23 of the 70 (33%) said they would see their private physician, 17 (24%) said they would notify their boss, and 2 (3%) said they would visit a health center.

Workers

Almost all the respondents (112, 96% of the 117 who answered) knew that pes- ticides had been used in suicide at- tempts, and 12 of the 130 survey re- spondents (9%) knew of someone who had been poisoned as a direct result of the use or misuse of pesticides. While 44 of 97 respondents (45%) believed that something could be done to prevent in- tentional deaths of this sort, relatively few indicated particular preventive measures that they favored.9

Training None

Introduction only Training provided by:

Technical agent Supervbor Ministry of Health PAHO or WHO

representatrve Other farmers SLBGA employees School

No. (%)

31 (25)

30 (25)

30 (251

14 (I 7)

9 (7)

3 f2)

2 (2)

2 (2)

7 UJ

ing or training by way of “introduction only.”

Most (71 of 97 respondents who an- swered, or 73%) said labels or directions were always affixed to their pesticide containers, while another 19 respondents (20%) said they were sometimes so af- fixed. However, 54 (43%) of 124 respond- ents who answered a question about comprehension said they did not under- stand the labels, and an additiona 12 (10%) said they only sometimes under- stood. As was to be expected, a failure to understand some or all of the labels was strongly associated with having not attended school (Yates corrected x2 = 18.15, p < 0.001).

Safety Practices

Of the 125 respondents who answered a question on training, 65 (53%) claimed to have received training in proper and safe pesticide use. As indicated in Table 3, which shows the stated sources of in- struction for those 122 respondents citing a source, technical agents were the pri- mary source of formal training. Unfor- tunately, fully half of these 122 workers indicated that they had received no train-

9Nine respondents suggested reducing access to pesticides by reducing their production, importa- tion, sales, or handling; six recommended educa- tion programs concerning hazards; four recom- mended that pesticides be securely locked up; and one suggested that intentional deaths could be pre- vented if pesticides were made to taste or smell more offensive.

Of the 66 subjects who said they did not understand the labels or only some- times understood them, 52 provided rea- sons, as follows: 31 of the 52 (60%) said they could not read; 10 (19%) said the labels were too difficult to read; 7 (13%) said they did not bother to read them; and 4 (8%) said the print was too smalI

to read.

.

Of 65 respondents who said they sometimes or always understood the la- bels and who answered a question about following the instructions, 18 (28%) said they aIways followed the instructions, 19

(29%) said they followed the instructions most of the time, 18 (28%) said they fol- lowed them some of the time, and 10 (15%) said they rarely followed them. No relationship was found between the like- lihood of a worker following the instruc- tions and his or her training, gender, or occupation.

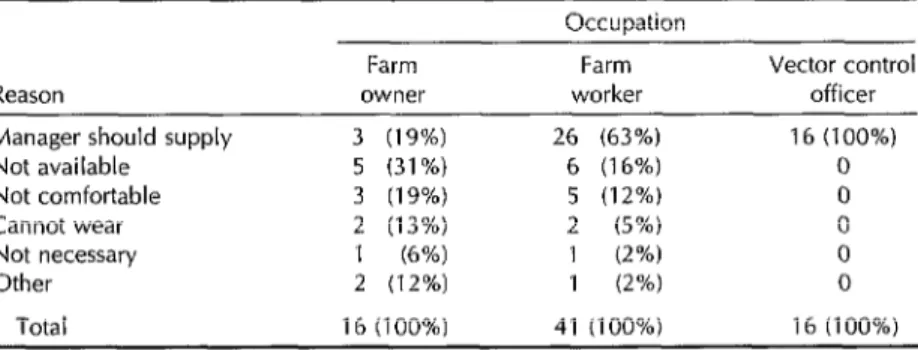

Despite their level of awareness of the hazardous nature of the chemicals being used, 82 of 127 respondents (65%) said they never wore protective clothing, and another 26 (20%) said they only wore it sometimes. While no relationships emerged between training, gender, age, education, and duration of employment on the one hand and the wearing of pro- tective clothing on the other, occupation was found related to the wearing of pro- tective clothing. Specifically, farm own- ers were significantly more likely than farm laborers and vector control officers to have worn protective gear at some time (x2 = 5.82, p < 0.02). Overall, 7 (6%) of the 127 respondents said they had worn goggles at some time, 17 (13%) said they had worn a respirator, 22 (17%) said they had worn rubber gloves, and 29 (23%) said they had worn rubber boots. The various reasons given by 73 respondents for not wearing protective gear are listed in Table 4. As can be seen, all of the vector control officers and most of the farm laborers said managers should sup- ply the gear.

Of 124 respondents who answered a question about smoking, 40 (32%) said they were smokers. A significantly higher percentage of males than females (39% versus 11%) said they were smokers at the time of the interview (Yates corrected x2 = 7.68, p < 0.02). Nine of the smokers (23%) said they had smoked while using pesticides.

Of 119 respondents who answered a question on other breaches of protective practices, 24 (20%) said they had eaten food while using a pesticide, and 11 (9%) said they had failed to plan the day’s work before going into the field.

At the end of a day during which pes- ticides were used, 89 (73%) of 121 re- spondents said they typically washed their entire bodies and changed their clothes. However, 13 others (11%) said they would be more likely to bathe but then put on their working clothes again; 18 (15%) said they would be likely to take only a partial bath or merely wash their hands; and 1 (1%) reported an inclination to only change clothes. Again, no relationship emerged between these various practices and the respondents’ gender, occupation, or for- mal training in pesticide use.

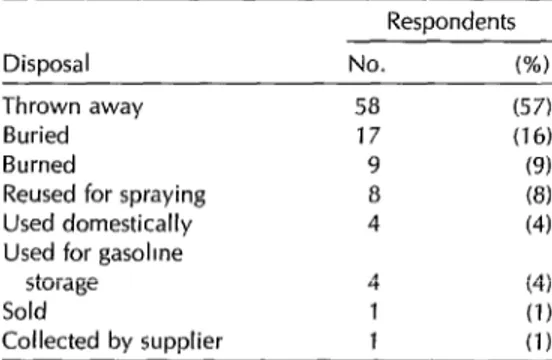

Regarding a question on disposal of used pesticide containers, 58 of the 102 respondents who answered said they simply discarded the pesticide containers when they were empty. Table 5 lists vari- ous ways in which the respondents said

Table 4. Reasons cited by 73 respondents for not wearing protective gear.

Occupation

Reason

Farm owner

Manager should supply 3 (19%) 26 (63%)

Not available 5 (31%) 6 (16%)

Not comfortable 3 (19%) 5 (12%)

Cannot wear 2 (13%) 2 (5%)

Not necessary 1 (6%) 1 (2%)

Other 2 (12%) 1 (2%)

Total 16 (100%) 41 (100%)

Farm Vector control

worker officer

16 (100%) 0 0 0 0 0 16 (100%)

Table 5. Ways in which 102 respondents said empty pesticide containers had been disposed of or reused.

Disposal

Respondents

No. (%)

Thrown away Buried Burned

Reused for spraying Used domestically Used for gasolme

storage Sold

Collected by supplier

58 (57)

17 (16)

9 (9)

8 (8)

4 (4)

4 (4)

1 (1)

1 (1)

empty pesticide containers had been dis- posed of or reused.

CONCLUSIONS

AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

This is the first study to document the prevalence of suboptima safety practices among workers using pesticides in the English-speaking Caribbean. The find- ings of greatest interest are those that identify modifiable attitudes, gaps in knowIedge, or management practices amenable to corrective action through ed- ucation or legislation.

Although the group of exposed work- ers surveyed was generally aware that pesticides are toxic, this knowledge did not always translate into adoption of safety measures. Sometimes lack of more de- tailed knowledge was responsible. For example, one apparent reason for failure to use protective gear was lack of aware- ness that the skin is a primary route of absorption (9). And while it was common for this information to be printed boldly on product labels, less than half of the users were capable of consistently under- standing written warnings.

Since higher levels of education were associated with younger respondents in this study, it seems reasonable to expect the literacy rate of the occupational groups

studied to improve over time. In the meantime, however, there is a clear need for pictorial representation of the hazards of skin exposure to these chemicals.

Even then, ensuring that accurate and understandable labels are affixed to a11 pesticide containers will not by itself lead to full compliance with directions. In this study, less than 60% of the individuals who said they understood the labels ac- tually followed the advice provided most of the time. The reasons for this noncom- pliance must be understood before a cor- rective course of action can be planned. For instance, poor coordination between workers and management could account for much of the failure to use protective gear. It is tie that some workers felt such gear to be uncomfortable or unnec- essary; but it is also true that a majority of the laborers felt that management should provide this equipment. The clear implication is that workers, manage- ment, and the government need to ac- cept shared responsibility for protecting the safety of exposed workers, and a sys- tem must be established for maximizing adoption of safety measures.

Thus far, training in pesticide appli- cation appears to have had minimal in- fluence on the workers’ safety practices. Those respondents who had received training were no more likely than their untrained colleagues to follow the in- structions on labels, wear protective gear, or bathe and change their clothes after a day of using pesticides. Mitigating cir- cumstances could have prevented the trained workers from practicing what they had been taught; even so, the quality of the safety instruction being provided and the reasons why more workers are not being trained should be examined.

For those interested in evaluating or improving safety training in Saint Lucia, it is worth noting that the vast majority of farms purchase their pesticides from a single supplier. This supplier, the Saint

Lucia Banana Growers’ Association, could therefore serve as a direct conduit for continuing education in safety practices. It should also be noted that since 70% of the pesticide users both prepare and apply pesticides, training needs to be directed toward both of these activities.

Another safety concern arises from the fact that over a quarter of the agricultural workers who responded to a question about pesticide storage stated that pes- ticides were being stored in their homes, and only half of those with pesticides at home said they were safely secured. This poses an unacceptable risk of pesticide poisoning (both intentional and uninten- tional) for these agricultural workers’ un- trained family members. Educational ef- forts, legislative interventions, and improved monitoring may all be needed to curb the practice of storing pesticides in the home.

In the event that a surveillance system is established to monitor pesticide poi- soning effects and trends, one should keep in mind that 28 of 70 respondents (40%) in this survey said they would tell no one if they believed they were ill as a result of working with pesticides. If workers are not encouraged to report symptoms, then a high degree of underreporting of symp- toms that are not life-threatening would need to be assumed.

While efforts were made to ensure that the survey sample in this study was rep- resentative of Saint Lucia’s occupation- ally exposed population, and while all the selected workers agreed to partici- pate, the possibility of volunteer bias must still be considered in assessing the an- swers to questions that were not an- swered by all the participants. For in- stance, the true rates of adherence to safety practices are likely to have been some- what lower than those reported here, since workers who had engaged in unsafe practices would be the ones most

likely to abstain from answering a direct query*

Overall, this study uncovered a num- ber of deficiencies in the training, knowl- edge, and safety practices of pesticide users in vector control programs and on both small and large farms in Saint Lucia. However, the study itself is only part of a considerably larger project. Current plans call for using the study results in the near future to design educational in- tervention programs capable of redress- ing gaps in the knowledge base and at- titudes of pesticide users, after which a repeat KAPB survey will be conducted to determine the effectiveness of these ed- ucational efforts. In addition, a surveil- lance system will be developed to mon- itor cases of acute and chronic pesticide poisoning; the management of pesticides will be evaluated with respect to their procurement, storage, distribution, la- beling, preparation for use, and methods of application and disposal; and results and recommendations arising from each phase of the project will be forwarded to exposed workers and to local authorities responsible for pesticide management. Plans are also being made to administer the KAPB survey to a sample of pesticide users in Trinidad and Tobago. It should be noted that the results of that survey could be quite different from the results reported here, especially because Trini- dad and Tobago’s economy is much less dependent on bananas than Saint Lu- cia’s, a circumstance that could signifi- cantly affect the attitudes and practices of pesticide users.

Acknowledgments. Support for this project has been provided by the U.S. National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSWCDC). The authors are indebted to Dr. Gilles Forget for his assistance in developing this project and his constructive review of an earlier ver- sion of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Demacque D. Economic importance of ag- 5. riculture in St. Lucia. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Risk Assessment of Agrockemi- cals in fke Eastern Caribbean. Castries, Saint

Lucia: 1985:74-78. 6.

Saint Lucia, Central Statistical Office. Gov- ernment statistics of Saint Lucia: annual over- seas trade report (part 1). Castries, Saint Lucia:

1990. 7.

Magloire L. Toxic chemical management program: banana pesticide life cycle and use in St Lucia. In: Proceedings of the Regional and National Management of Industrial Ckem- 8. icals Workshop. Castries, Saint Lucia: 1989; chapter 14A.

Trundle D, Marcia1 G. Detection of cholin- esterase inhibition: the significance of cho- linesterase measurements. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1988;18(5):345-352.

Phoon WO, Jeyaratnam J, Lun KC, et al. Pesticide project (Southeast Asia). Ottawa, Canada: International Development Re- search Centre; 1986. (Unpublished report). Jeyaratnam J, Lun KC, Phoon WO. Survey of acute pesticide poisoning among agri- cultural workers in four Asian countries. Bull WHO. 1987;65(4):521-527.

Last JM. A dictionary of epidemiology (2nd edition). New York: Oxford University Press; 1988:70.

Savage El’, Keefe TJ, Mounce LM, Heaton 9. World Health Organization. Safe use of pes- RK, Lewis JA, Burcar PJ. Chronic neuro- ticides. Geneva: 1985:lO. (WHO technical logical sequelae of acute organophosphate report series 720).

444

pesticide poisoning. Arch Environ Health. 1988;43(1):38-45.

Health Executives Development Progrum

Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, will offer its 36th annual Health Executives Development Program from 9 to 15 May 1993. More than 25 distinguished faculty will present current thinking on health policy, regulation, planning, and management in both the United States of America and abroad. The program is open to all health care executives. A special two-day seminar on the U.S. health care system is offered to international participants in preparation for subsequent

sessions.

For further information contact Health Executives Development Pro- gram, N222 Martha Van Rensselaer Hall, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 14853, USA; telephone (607) 255-8013.