See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/285750099

New preliminary data on the exploitation of

plants in Mesolithic shell middens: the

evidence from plant macroremains from the...

Conference Paper · November 2015 CITATIONS 2 READS 84 3 authors: Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Mid-Holocene hunter-gatherers and shell midden site structure and functionality in Atlantic Europe and Japan View project Mauranus View project Ines L. Lopez-Doriga Wessex Archaeology 30 PUBLICATIONS 55 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Mariana Diniz University of Lisbon 25 PUBLICATIONS 77 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Pablo Arias Universidad de Cantabria 111 PUBLICATIONS 664 CITATIONS SEE PROFILEAll content following this page was uploaded by Ines L. Lopez-Doriga on 05 December 2015.

Muge 150th

:

The 150th Anniversary

of the Discovery of Mesolithic

Shellmiddens—Volume 1

Edited by

Nuno Bicho, Cleia Detry, T. Douglas Price

and Eugénia Cunha

Muge 150th:

The 150th Anniversary of the Discovery of Mesolithic Shellmiddens— Volume 1

Edited by Nuno Bicho, Cleia Detry, T. Douglas Price and Eugénia Cunha This book first published 2015

Cambridge Scholars Publishing

Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2015 by Nuno Bicho, Cleia Detry, T. Douglas Price and Eugénia Cunha and contributors

All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN (10): 1-4438-8007-8 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8007-7

T

ABLE OF

C

ONTENTS

Foreword ... ix List of Contributors ... xi Chapter One ... 1 Carlos Ribeiro and Francisco António Pereira da Costa: Dawn

of the Mesolithic Shell Middens of Muge (Salvaterra de Magos) João Luís Cardoso

Chapter Two ... 19 The Archaeological Excavations at Muge Shell Middens in the 1930’s: A New Contribution to the History of its Investigation

Ana Abrunhosa

Chapter Three ... 33 Sources for the Reconstruction of Cabeço da Arruda

Mary Jackes, David Lubell, Pedro Alvim and Maria José Cunha

Chapter Four ... 45 Cabeço da Arruda in the 1860s

Mary Jackes, David Lubell, H. Cardoso, José Anacleto and Chris Meiklejohn

Chapter Five ... 59 Antler Debitage in Muge Shell Middens: The Collections

of the Geological Museum Marina Almeida Évora

Chapter Six ... 77 Reading the Lithics in Flint of Cabeço dos Morros Shell Midden

Table of Contents vi

Chapter Seven ... 89 Marine Invertebrates and Models of Economic Organization

of the Coastal Zone during the Mesolithic: French and Portuguese Examples

Catherine Dupont and Nuno Bicho

Chapter Eight ... 105 What’s New? The Remains of Vertebrates from Cabeço da Amoreira— 2008-2012 Campaigns: Preliminary Data

Rita Dias, Cleia Detry and Alexandra Pereira

Chapter Nine... 119 Preliminary Techno-Typological Analysis of the Lithic Materials

from the Trench Area of Cabeço da Amoreira (Muge, Central Portugal) João Cascalheira, Eduardo Paixão, João Marreiros, Telmo Pereira and Nuno Bicho

Chapter Ten ... 135 New Functional Evidence for Human Settlement Organization

from the Mesolithic Site of Cabeço da Amoreira (Muge): Preliminary Lithic Use-Wear Analysis

João Marreiros, Juan Gibaja, Eduardo Paixão, Telmo Pereira, João Cascalheira and Nuno Bicho

Chapter Eleven ... 147 Raw Material Procurement in Cabeço da Amoreira, Muge, Portugal

Telmo Pereira, Nuno Bicho, João Cascalheira, Célia Gonçalves, João Marreiros and Eduardo Paixão

Chapter Twelve ... 161 The Midden Is On Fire! Charcoal Analyses from Cabeço da Amoreira (Muge Shell Middens)

Patrícia Diogo Monteiro, Nuno Bicho and Lydia Zapata

Chapter Thirteen ... 177 Fire and Death: Charcoal Analyses from Two Burials in Cabeço

da Amoreira (Muge Shell Middens)

Muge 150th Volume 1 vii

Chapter Fourteen ... 185 The Importance of New Methodologies for the Study of Funerary

Practices: The Case of Cabeço da Amoreira, a Mesolithic Shell Midden (Muge, Portugal)

Olívia Figueiredo and Célia Gonçalves

Chapter Fifteen ... 199 The Mesolithic Skeletons from Muge: The 21st Century Excavations

Maria Teresa Ferreira, Cláudia Umbelino and Eugénia Cunha

Chapter Sixteen ... 209 Life in the Muge Shell Middens: Inferences from the New Skeletons

Recovered from Cabeço da Amoreira

Cláudia Umbelino, Célia Gonçalves, Olívia Figueiredo, Telmo Pereira, João Cascalheira, João Marreiros, Marina Évora, Eugénia Cunha and Nuno Bicho

Chapter Seventeen ... 225 Tracing Past Human Movement: An Example from the Muge Middens T. Douglas Price

Chapter Eighteen ... 239 Cranial Morphology and Population Relationships in Portugal

and Southwest Europe in the Mesolithic and Terminal Upper Palaeolithic Christopher Meiklejohn and Jeff Babb

Chapter Nineteen ... 255 The Late Mesolithic of Southwest Portugal: A Zooarchaeological

Approach to Resource Exploitation and Settlement Patterns Peter Rowly Conwy

Chapter Twenty ... 273 Living On the Edge of the World: The Mesolithic Communities

of the Atlantic Coast in France and Portugal Grégor Marchand

Chapter Twenty One... 287 Settlement and Landscape: Poças de São Bento and the Local

Environment Lars Larsson

Table of Contents viii

Chapter Twenty Two ... 301 At the Edge of the Marshes: New Approaches to the Sado Valley

Mesolithic (Southern Portugal)

Pablo Arias, Mariana Diniz, Ana Cristina Araújo, Ángel Armendariz and Luis Teira

Chapter Twenty Three... 321 Lithic Materials in the Sado River’s Shell Middens: Geological

Provenance and Impact on Site Location

Nuno Pimentel, Diana Nukushina, Mariana Diniz and Pablo Arias

Chapter Twenty Four... 333 High Resolution XRF Chemostratigraphy of the Poças de São Bento

Shell Midden (Sado Valley, Portugal)

Carlos Simões, Eneko Iriarte, Mariana Diniz And Pablo Arias

Chapter Twenty Five ... 347 New Preliminary Data on the Exploitation of Plants in Mesolithic Shell Middens: The Evidence from Plant Macroremains from the Sado Valley (Poças De S. Bento And Cabeço Do Pez)

Inés L. López-Dóriga, Mariana Diniz and Pablo Arias

Chapter Twenty Six ... 361 Lithics in a Mesolithic Shell Midden: New Data from the Poças de São Bento (Portugal)

Ana Cristina Araújo, Pablo Arias and Mariana Diniz

Chapter Twenty Seven... 375 Pots for Thought: Neolithic Pottery in Sado Mesolithic Shell Middens

C

HAPTER

T

WENTY

-F

IVE

N

EW

P

RELIMINARY

D

ATA

ON THE

E

XPLOITATION OF

P

LANTS

IN

M

ESOLITHIC

S

HELL

M

IDDENS

:

T

HE

E

VIDENCE FROM

P

LANT

M

ACROREMAINS

FROM THE

S

ADO

V

ALLEY

(P

OÇAS DE

S. B

ENTO AND

C

ABEÇO DO

P

EZ

)

I

NÉS

L. L

ÓPEZ

-D

ÓRIGA

1, M

ARIANA

D

INIZ

2AND

P

ABLO

A

RIAS

31 Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas (IIIPC),

Universidad de Cantabria, Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. de los Castros s/n, Santander 39005, Cantabria, Spain.

ines.lopezl@alumnos.unican.es;

2 Centro de Arqueologia (UNIARQ),

Departamento de História, Faculdade de Letras, Universidade de Lisboa, Alameda da Universidade 1600-214, Lisboa, Portugal,

m.diniz@fl.ul.pt

3 Instituto Internacional de Investigaciones Prehistóricas (IIIPC),

Universidad de Cantabria, Edificio Interfacultativo, Avda. de los Castros s/n, Santander 39005, Cantabria, Spain

ariasp@unican.es

Abstract

Within the framework of the Sado Meso project, two shell middens (Poças de S. Bento and Cabeço do Pez) in the Sado valley, Portugal, have been exhaustively sampled for plant macro-remains, in an effort to overcome two problems in prehistoric research: firstly, the scarcity of direct data about plant use by the Mesolithic peoples of Atlantic Iberia,

Chapter Twenty-Five 348

and secondly, the neglect of sampling strategies for the recovery of plant macro-remains in the shell midden research tradition. The flotation technique has been applied to 100% of the sediment obtained during the new excavation campaigns and a considerable number of samples have been studied. We now have substantial data about the exploitation of a wide range of wild plants which might have played a role of economic importance within the human groups at the end of the Mesolithic.

Introduction

One of the concerns of prehistoric archaeology, no less for the Mesolithic and shell midden specialised research, is the exploitation of natural resources by past human groups. However, the view that is often obtained from most research projects on shell middens is biased towards specific types of resources. It is well known that the shell middeners ate abundant shellfish and even used shells for technological activities, many of them involving plants (Cuenca-Solana et al. 2011). But did they eat shellfish in green sauce? Were nettle fabrics on trend? The use of plants is scarcely known and is, for the most part, based on approximate indirect evidence or restricted to that of wood charcoal. The only known Mesolithic, non-woody plant, archaeological macro-remains (seeds and fruits) in Portugal come from Prazo, a northern site (Monteiro-Rodrigues 2012); wild olive fruits and acorns are reported from several unspecified Middle and Late Holocene sites (Queiroz & Mateus 2006). A site in the Muge shell midden complex, Cabeço da Amoreira, has been sampled for plant macro-remains but the actual results of seeds and fruits have never been published (Wollstonecroft et al. 2006). One of the sites presented here was partially floated for plant macro-remains in previous research projects (unpublished), but to no avail probably due to the very limited sampling (Larsson, pers. com.).

Plants must have equally been used for dietary and technological purposes, among others, but the study of plant remains is often excluded from research aims. Approaches to plant use from indirect sources, such as stable isotopes (e.g. Umbelino et al. 2007) or dental pathologies (e.g. Jackes 2009), are widespread and understandable for the study of restricted materials from old excavations. Nevertheless, this should not be the case for current excavations, as it is now known that plant remains are indeed preserved in most Holocene archaeological sites, and are found whenever they are appropriately looked for. The methodological vicious circle of not sampling and recovering carefully because it is supposed that nothing is going to appear, so nothing appears because appropriate

New Data on the Exploitation of Plants in Mesolithic Shell Middens 349

sampling and recovery methods have not been applied, should be disentangled. How is it possible to discuss the socioeconomic differences or continuities between Mesolithic and Neolithic populations if plant recovery strategies are omitted in research projects? Are plant remains really absent in shell middens? How can the absence of finds evidence of plant remains be differentiated from the cases where plants are truly absent, if reports do not specify the methodologies employed or whether specific plant recovery techniques existed at all?

Materials and Methods

Poças de S. Bento (PSB) and Cabeço do Pez (CPZ) are two open-air shell midden sites in the Sado valley, Portugal, discovered and excavated in the 1950s and 1980s (Arnaud 1989; Larsson 2010) and currently under study by the Sado Meso project (see Arias et al., this volume). They can be broadly characterized as extensive (about 4000 m2) but low (1.5 m thick) shell middens, which are areas of the accumulation of refuse of mostly shellfish remains, alternated with other domestic functional spaces (hearths, flint-knapping areas, etc...) and human and dog burials. Abundant archaeological remains, from mammal and fish bones, lithics, pottery fragments to charcoal, have been recovered and are under study (for further preliminary details see Araújo et al., Diniz & Cubas, Pimentel et al., Duarte et al., Stjerna, this volume).

One hundred percent of the excavated sediment (except the topsoil level) has been processed with two Syraf-type flotation machines (at approximately 7 minutes per sample of about 10dm3 of sediment). Flotation produces two fractions that are sorted separately, a light one (flot) containing all charred plant material and floating soil components above 250 μm in size, and a heavy one, containing other archaeological remains and dense soil components above 1 mm in size. Sorting the archaeological materials from the heavy fraction was quicker and more precise than sorting from dry-screened fractions, as everything was clean and easy to catch. A representative sample of flots from the Late Mesolithic layers has been studied to this date and is here presented. PSB samples from excavation area nº 1, extensively excavated from 2010 to 2013 (12 m2), have been chosen for study: all flots from the dog burial (SU8, n=13), plus 50 of each shell midden layer (n=100 total flots from the two shell midden layers, SU3=7 and SU12). Still under study are samples from the upper layer which are probably Neolithic. CPZ samples from the test pit of 2010 come from SU2, and samples from underlying layers await further study. Flot samples have been screened with 2 mm to

Chapter Twenty-Five 350

250 μm meshes and sorted, the smaller fractions under a Leica S8APO binocular microscope. Only charred plant material has been analysed; several uncharred seeds are likely part of the modern natural seed rain, so have been rejected from the study as recent intrusions introduced by bioturbation or added during excavation or processing. Quantification is based on whole individuals or quantifiable fragments (e.g. embryos in grasses). An example of each taxa has been photographed with a Canon EOS450D photo camera, photo-stacking has been carried out with the software Helicon Focus and final processing (background cleaning and scaling) with GIMP. Some of the plant macro-remains identified have been chosen for 14C dating, and results are still awaited.

Results

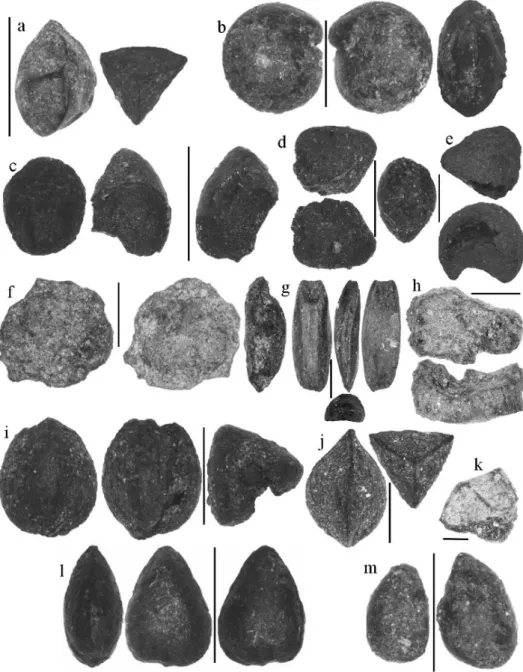

Surprisingly (or not really), plant macro-remains do really exist in shell middens! So far, a series of species has been consistently recovered (Fig. 25.1; Table 25.1): there are no obvious differences between the different archaeological units of PSB, while the repertoire at CPZ is small (only 1 sample from SU2 provided determinable plant macro-remains other than wood charcoal) but considerably different. The potential uses for the different taxa have been proposed according to ethnographic sources (Fern 1992-2010).

Discussion

The studied samples have given a probable representative group of plant macro-remains arising from different potential activities of plant-resource exploitation, from food and drink procurement to other domestic activities (dyeing, fibre weaving, medicine preparation, etc...). Charred plant macro-remains do not represent all the plant resources exploited by past human groups; there are other types of plant remains that complement the information. There can be sites where plants might not be preserved in a specific way (but most certainly they will probably be preserved in at least one of the other many types of preservation forms: charred macro-remains, phytoliths, starch grains, pollen, etc...). Shell middens, because of the high level of calcium carbonate, are not ideal deposits for the preservation of charred plant macro-remains which become easily eroded in that ambient (Braadbaart et al. 2009). Fortunately, at the PSB and CPZ shell middens at least, charred plant remains are preserved in considerable quantities and relatively good preservation so as to allow for a

New Data on the Exploitation of Plants in Mesolithic Shell Middens 351

consideration of the potential activities in which plant resources were used.

It is important to note that all remains were scattered along the different archaeological units: this is a typical tertiary deposition context (Fuller et al., 2014) in which the assemblage of plant remains probably arises from different activities of carbonization and it is not in the original position where they were charred. This means that it is very difficult to recognise assemblages of remains arising from single specific processing activities. This mixing and redepositioning of by-products from different activities probably accounts for the high presence (of hundreds of fragments) of non-woody plant charred material which is extremely fragmented and eroded so as to be morphologically or anatomically unrecognisable.

The most plausible explanation for plant parts being carbonised is during accidents in hearths (López-Dóriga 2012); the reasons why these plants or plant parts are brought into contact with fire (mainly at discarding or processing, as de-insecting, drying, cooking...) are another matter and they might vary according to each plant part and its uses and properties. Charred plant remains are not usable any more: their presence in the midden layers is probably a result of sweeping hearths and processing areas and discarding the sweep in this area of accumulation of domestic refuse (Miksicek 1987). The possibilities of the charred remains arising from natural causes unrelated to human activities is extremely small.

Chapter Twenty-Five 352

Figure 25.1. Specimens of plant macroremains from the main identified taxa from Poças de S. Bento, in several views. Scale bars = 1mm. From left to right and up to down: a. Anagallis arvensis L. / monelli L. (seed), b. Chenopodium album L. (seed), c. cf. Ficus carica L. (seed fragment), d. cf. Geranium L. sp. (seed fragment), e. Malva L. sp. (seed), f. Linaria Mill. sp. (seed), g. Lolium L. sp. (seed), h. Pinus pinea L. (nutshell fragment), i. Polygonaceae (seed), j. Rumex L. sp. (seed), k. Pinus pinea L. (cone bract-scale fragment), l. Urtica L. sp. (seed), m. cf. Viola sp. (seeds).

N ew Da ta o n th e E xp lo it at ion o f Pl an ts in Me so li th ic S he ll M id de ns 353 T able 25. 1. Id ent ified plan t m acr or em ai ns fr om P S B an d C PZ (+ in di ca te s no n-qu ant if ia bl e rem ai ns) . Ta xa ( pl an t p ar t) C om m on n am e (E N, P ,ES) K now n us es Nº of items per context PSB 3=7 (sh el l m idd en) P S B 8 (d og buri al ) P SB 12 (sh el l m idd en) Tot al PS B CPZ 2 (sh el l m idd en) A na ga ll is ar ve ns is L . / mon elli L . Pi m per nel , m or ri ão, m ur aj e Food, m ed ic ine , soap 1 1 B ra ss ic ac ea e [C ru ci fe ra e] ( se ed ) C ab ba ge f am ily , cr uc íf era s F oo d, oi l 1 Ch en op odi um al bu m L . ( se ed ) F at h en , ca ta ss ol , c añ iz o Food, m edi ci ne , d ye 1 1 cf . F ic us c ar ic a L . (s ee d fr ag m en t a nd fru it fl es h fr agm en t) Co mmon fi g, fi go , h ig o Food, me dicin e 1 1 2 cf . G era nium L . sp .(s ee d) C ra ne sb il l, pa mp il ho, ge ra ni o M an y, de pe nd in g on th e sp ec ies 4 4 Lin aria M il l. sp . (s ee d) Toa df la x, an sa ri na , g al lit o Food, m ed ic ine , dy e, in sect ici de 1 1

C ha pt er T w en ty -F iv e 354 Lol iu m L . s p. ( se ed ) R ye gr as s, jo io , ba ll ic o C er ea l: f oo d, fod der 4 26 30 M al va L . s p. ( se ed ) M al lo w , m al va , m al va vi sc o Fo od , oi l, m ed ic ine , fibre, dy e 1 1 2 M ed ic ag o L . s p. (s ee d) M ed ic k, lu ze rn a, a lf al fa Fo od, f od der , me dic ine 6 P in us pi ne a L . ( con e br ac t-es ca le fra gm ent ) U m br el la -pi ne , pin he ir o ma ns o, pi no pi ño ne ro F ood , o il , f ue l 36 6 25 67 1 P in us pi ne a L . (nu tshell frag ment) 1 1 Poa ce ae [G ra m in ea e] ( se ed ) G ra ss es , gr am as , gr am ín ea s M an y, de pe nd in g on th e sp ec ies 2 2 P ol yg ona ce ae ( seed ) Kn ot wee d fa m il y, ce nt id on ia s M an y, de pe nd in g on th e sp ec ies 2 2 R ume x L . s p. ( se ed ) Do ck s and sor re ls , l ab aç a, ac ed er a Food, m ed ic ine , dy e, cu rdlin g age nt 1 1 2

N ew Da ta o n th e E xp lo it at ion o f Pl an ts in Me so li th ic S he ll M id de ns 355 Ur ti ca L . s p. ( se ed ) N et tle , u rt ig a, or ti ga Foo d, dri nk, oi l, m ed ic in e, dy e, f ib re , in se ct repe llent 1 1 Vi ci a L ./ L at hy ru s L . ( se ed ) V et che s/v etc hl in gs , er vi lh ac as /c hí ch ar os , ve za s/ gu ij as Fo od , f od de r 1 cf . V io la L . s p. ( se ed ) W il d pa ns y, amo r pe rf ei to br av o, pen sa mi ent o si lv es tre Foo d, dri nk, m ed ic ine , perf ume 5 1 6 In deter minate s eed 5 5 10 In de te rm in at e fr ui t frag ment 4+ 3+ 15+ 22+++ Ind eterminate no n-w oo dy p la nt ti ss ue (am ong whi ch pos si bl e pa re nc hy m ae ) + + + + + + + In deter minate s talk or pedi ce l 2 2

C ha pt er T w en ty -F iv e 356 F un ga l sc le ro ti a tp . Cenococcum ge op hi lu m + + + + + + Te rm ite f ae ca l pe lle ts + + + + + + Tot al n º of r em ai ns 55 + 17 + 84 + 15 6+ ++ 9+

New Data on the Exploitation of Plants in Mesolithic Shell Middens 357

Within the flotation samples, other types of ancient and modern remains have been recovered. On the one hand, uncharred items, such as seeds, mycorrhizal fungi sclerotia (tp. Cenococcum geophilum) and termite and rodent coprolites (very abundant in some layers), are all probably modern biological remains. On the other hand, charred items, such as dead-wood termite faecal pellets and fungi sclerotia are quite likely ancient remains that were accidentally charred when dead wood and roots were used as fuel or cooked. Termites themselves might have been cooked for eating. Two types of sources of bioturbation can thus be differentiated, accounting for some of the apparently non-anthropic negative structures discovered upon excavation: plant roots (evidenced in the presence of fungi sclerotia and the fragments of plant roots) and furrowing animals (evidenced in the rodent coprolites). Both of these probably explain the introduction of uncharred seeds in the archaeological layers, as bioturbation activity can cause displacement of plant parts both up and down in soils (Miksicek 1987). The excavation and flotation processes can also account for the introduction of uncharred seeds and insects. The possibility that the charred plant macro-remains are of recent introduction is very small: on the one hand, furrowing animals transport uncharred seeds for their consumption, but not charred unpalatable ones (Miksicek 1987); on the other hand, there is not a correlation between the uncharred seeds and the charred ones: although some taxa appear in both states of preservation, most uncharred seeds are not preserved in a charred form and vice-versa.

Regarding palaeoenvironment and resource procurement strategies, these plant remains tell us that the past human groups that brought them to the site exploited several different ecological environments: meadows with grasses (Poaceae, Lolium sp.) and other herbs and possibly scattered umbrella pines (Pinus pinea); and nutrient rich soils such as those in which nettle (Urtica sp.), chenopods (Chenopodium album), docks and sorrels (Rumex sp.) thrive.

Aside from informing about past plant resource exploitation and environment, plant remains can help an understanding of the general taphonomy of deposits and allow an insight into chronology; e.g. at one of our excavation areas from 2010 at PSB, cereal seeds were observed during the flotation of samples of deep origin; further laboratory examination concluded they were naked wheat grains, and this fact helped with the decision to exclude this pit (with intrusive remains) from further excavation. Coprolites identified in flotation samples help to determine the character of pits that are suspected to be potential post-holes. Plant

Chapter Twenty-Five 358

remains also help to establish the chronology of the site and calibrate the reservoir correction for aquatic or aquatic-based-diet individuals.

Conclusions

Charred plant remains might be recovered in most Holocene archaeological sites if adequate sampling and recovery strategies are applied, regardless of open-air conditions, geology, etc... Studies of plant remains are a keystone for the reconstruction of past human activities, particularly, but not exclusively, concerning the exploitation choices of the natural resources in the environment. This study has proven that plant remains can be relatively abundant and diverse in Mesolithic open-air shell midden sites and have a high informative potential in regard to diverse human activities, from food procurement to the development of technological activities. The study of plant remains could and should be an ineludible part of research projects, as they are relevant to an understanding of both the Mesolithic adaptations and the nature of continuities and discontinuities in the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition.

Acknowledgements

Without the help of the members of the Sado Meso project, who have contributed with their technical help in the sampling and flotation processes at PSB and CPZ, this work would not have been possible. Marie-Pierre Ruas and colleagues at the Museum Nationcal d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, have helped in the taxonomical determination of some of the plant remains presented here.

This research is included in the projects "Coastal transitions: A comparative approach to the processes of neolithization in Atlantic Europe" (COASTTRAN) (HAR2011-29907-C03-00), funded by the VI Plan Nacional de Investigación Científica, Desarrollo e Innovación Tecnológica 2008-2011 of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and "Retorno ao Sado: Um caso entre os últimos caçadores-recolectores e a emergência das sociedades agropastoráis no sul de Portugal" (PTDC/HIS-ARQ/121592/2010), granted by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia of the Portuguese Ministry of Education and Science.

New Data on the Exploitation of Plants in Mesolithic Shell Middens 359

References

Arnaud, J. 1989. The Mesolithic communities of the Sado Valley, Portugal, in their ecological setting. In: Bonsall, C. (Ed.), The Mesolithic in

Europe. John Donald Publishers, Edinburgh, pp. 614-631.

Braadbaart, F.; Poole, I. & van Brussel, A. A. 2009. Preservation potential of charcoal in alkaline environments: an experimental approach and implications for the archaeological record. J Archaeol Sci 36: 1672-1679.

Cuenca-Solana, D., Gutiérrez-Zugasti, I. & Clemente-Conte, I. 2011. The use of molluscs as tools by coastal human groups: contribution of ethnographical studies to research on Mesolithic and early Neolithic contexts in Northern Spain. J. Anthr. Res. 67: 77-102.

Fern, K. 1992-2010. Plants For A Future: Plant Species Database, http://www.pfaf.org. [10th November 2013, last accessed]

Fuller, D. Q., Stevens, C. J. & McClatchie, M. 2014. Routine Activities, Tertiary Refuse and Labor Organization: Social Inference from Everyday Archaeobotany. In: Madella, M., Savard, M. (Eds.), Ancient

Plants and People. Contemporary Trends in Archaeobotany. Tucson:

University of Arizona Press.

Jackes, M. 2009. Teeth and the Past in Portugal: Pathology and the Mesolithic-Neolithic Transition. In: Koppe, T., Meyer, G., Alt K.W. (Eds.), Teeth and Reconstruction of the Past. Comparative Dental

Morphology. Front Oral Biol. Basel, pp. 167172.

Larsson, L. 2010. Shells in the sand: Poças de Sao Bento - a Mesolithic shell midden by the river Sado, Southern Portugal. In: Armbruester, T., Hegewisch, M. (Eds.), On Pre- and Earlier History of Iberia and

Central Europe: Studies in honour of Philine Kalb. Bonn: Habelt,

pp.29-43.

López-Dóriga, I. 2012. Reconstructing food procurement in prehistory through the study of archaeological plant macroremains (seeds and fruits). In: Cascalheira, J., Gonçalves, C. (Eds.) Actas das IV jornadas

de jovens em investigaçao arqueológica - JIA 2011, 167. Promontoria

Monografia Faro: Universidade do Algarve, pp. 167-172.

Miksicek, C. H. 1987. Formation processes of the archaeobotanical record.

Adv. Archaeol. Method Theory 10: 211.

Monteiro-Rodrigues, S. 2012. Novas datações pelo carbono-14 para as ocupações holocénicas do Prazo (Freixo de Numão, Vila Nova de Foz Côa, Norte de Portugal). Estudos do Quaternário 8: 22-37.

Queiroz, P. F. & Mateus, J. E. 2006. Approaching Ancient Territories in

Chapter Twenty-Five 360

conference) 15th Conference of the UISPP.

Umbelino, C., Pérez-Pérez, A., Cunha, E., Hipólito, C., Freitas, M. & Cabral, J. 2007. Outros sabores do passado: um novo olhar sobre as comunidades humanas mesolíticas de Muge e do Sado através de análises químicas dos ossos. Promontoria 5: 45-90.

Wollstonecroft, M. M., Snowdon, L., Lee, G. & Agustin, P. 2006. Archaeobotanical sampling at Cabeço da Amoreira: preliminary results of the 2003 field season. In: Bicho, N., Veríssimo, H. (Eds.), Do

Epipaleolítico ao calcolítico na Peninsula Ibérica. Centro de Estudos

de Património, Universidade do Algarve, 5562.

View publication stats View publication stats