The reverse migration decision and occupational outcomes:

A Self- Determination Theory perspective

Solange Cabral Francisco Goncalves

Dissertation submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of

Master in Human Resources Management

Supervisor:

Mestre Alzira Duarte, ISCTE Business School, Department of Human Resources and Organizational Behaviour

September 2018

The

re

v

er

se

m

igrat

ion

decision

a

n

d

o

ccup

ation

al

o

u

tco

m

es: A

Se

lf

-

Deter

m

in

atio

n

T

h

e

o

ry p

ersp

ectiv

e

Solan

ge Ca

br

al

F

ra

nc

is

co

G

onc

al

ve

s

The reverse migration decision and occupational outcomes: A Self-

Determination Theory perspective

Solange Cabral Francisco Goncalves

Dissertation submitted as partial requirement for the conferral of

Master in Human Resources Management

Supervisor:

Mestre Alzira Duarte, ISCTE Business School, Department of Human Resources and Organizational Behaviour

Abstract

Return migration has a great impact for all parties involved, considering that motivation greatly shapes the migration and indeed the return migration experience it is beneficial to explore the motivation behind a migration decision and understand how this shapes the processes that follow. This study extends current research in migration by considering the motivation behind the decision in greater depth through the Self-Determination Theory. Semi-structured interview were used to explore motivation in this context and consider how this shaped behavioural and occupational outcomes. Overall, we found that employment opportunities were a greater motivator, and this greatly influenced the preparation undertaken following the migration decision. We also found that while social motivations were not considered when making the decision, the social network was used as a tool for research following the return migration decision.

Keywords

International Migration, Return Migration, Motivation, Job seeking activities

JEL Classifications:

Resumo

A migração de retorno tem um grande impacto para todas as partes envolvidas. Considerando que a motivação molda grandemente a migração e, de fato, a experiência de migração de retorno; explorar a motivação por trás de uma decisão de migração e observar como isso molda os processos que se seguem ia beneficiar o nosso entendemento nesta area. Este estudo amplia as pesquisas atuais em migração, considerando a motivação por trás da decisão em maior profundidade através da Teoria da Autodeterminação. Entrevista semi-estruturada foi usada para explorar a motivação neste contexto e considerar como isso moldou os resultados comportamentais e ocupacionais. No geral, descobrimos que as oportunidades de emprego era o motivador maior, e isso influenciou muito a preparação realizada após a decisão de migração. Também descobrimos que, embora as motivações sociais não tenham sido consideradas na tomada de decisão, a rede social foi usada como ferramenta de pesquisa após a decisão de migração de retorno.

Palavras-chave

Migração internacional, Migração de retorno, Motivação, Procura de emprego

Classificação JEL:

Table of Contents

I Title II Abstract

III Abstract (Portuguese)

1 Introduction………...1

2 Literature Review………..2

2.1 International Migration 2

2.1 Self Determination Theory 10 3 Methodology……….13

3.1 Approach 13

3.2 Participants and sampling 13 3.3 Materials 15

3.4 Analysis 18

4 Results….……….…..20

4.1 Initial Migration and decision 20 4.2 Reason behind the decision 21 4.3 Social Influence 23 4.4 Preparation 24 4.5 Reflections 24 4.6 Employment Considerations 27 5 Discussion……….…….30 6 Conclusions….………..36 7 References…...……….…….40 8 Annexes……….44

Annex 1 Interview Guide 44

Annex 2 Demographic Information Form 46

Annex 3 Transcript Coding Extract 47

Appendix 8.3.1 Question Host country 47

Appendix 8.3.2 Question Family / Friends 49

Appendix 8.3.3 Question Employment Search 51

Index of tables

1 Introduction

International migration occurs for a number of reasons and takes on many forms; the perspective on migration has also expanded over the years with considerations being made to the temporary nature of migration (Dustmann and Weiss, 2007). Research that considered return migration identified many factors that contribute to the decision, (King and Christou, 2014). Motivation has been a key discussion point addressed in migration literature and theories, with focus on the motivation behind the decision considered crucial to the migration experience as well as the return. Migration literature, does not however explore the motivation underlying a return migration decision in great depths. Often assumptions are made based on the outward migration motivation or the return migration decision is a theme that emerges when focusing on other aspects of migration (Legido-Quigley et al., 2015).

To address this, the current study produced as part of a Masters in Human Resources Management intends to add to migration literature by focusing on the type of motivation behind a return migration decision, for this, the Self-Determination Theory (Ryan and Deci, 1985) will be used as the framework for investigation. The theory proposes that motivation is on a continuum, the continuum posits motivation from amotivation; a lack of motivation, to internal motivation, a point where a task is undertaken for its own value and merit. By considering motivation in this way when looking at a return migration decision, we can consider migration and its influence in greater depth. The study will consider if motivation type is in any way linked to occupational decisions and outcomes, something that is often discussed within migration literature due to the economic rationale behind migration.

Owing to this, the research will consider the practical implications of applying SDT when considering a reverse migration decision. The study will also go on to consider the themes that emerge when considering migration in this way, and finally, we will consider the impact this has on occupational decisions and outcomes. A qualitative approach was used as it allows for better exploration of the nuances of a migration decision and the subsequent processes undertaken by participants to not only migrate but also occupational processes that followed.

The following section will consider the migration literature both outward and return migration; so that we understand the current perspectives and the existing themes. This will be followed by an additional look at the Self-Determination Theory (SDT) as the underlying framework used to shape the data collection and resulting observations. Section four will cover the design and the methods followed, which will lead onto the results section. Following this the conclusions will be outlined. To end we will consider the limitations of the study and points for consideration in future research.

2. Literature Review

2.1 International Migration

Migration to another country may not be permanent given a host of changes creating an ever-increasing reality of reverse or re-migration. There are many motivating factors for organizations, individuals and social networks that exist. Ultimately many outcomes exist for all parties involved, making migration a high point of discussion at any given moment. A variety of benefits have been acknowledged to both host and home countries. With respect to sending countries the impact on poverty reduction may be significant (Borodak and Piracha, 2011). It has been argued that migration has stimulated a growth of skill and knowledge as a consequence of needs, as well as those intending to migrate preparing themselves for foreign job markets, however failing to actualize the initial migration and benefitting the home country (Ambrosini et al., 2015; Güngör and Tansel, 2014). Negative consequences for home countries have also been highlighted hence the previous trend of referring to migration as “Brain Drain” (Docquier and Rapaport, 2011; Güngör and Tansel, 2014). For those that return, much impact has been acknowledged, including the effects on labour markets through engagement with the workforce, and the impact of remittances (Ambrosini et al., 2015; Borodak and Piracha, 2011; Piracha and Vadean, 2010). Benefits to the host countries have been highlighted as the investment that migrants made, either through formal education or professional experience and the contributions this has had on the labour force. Also noted is reduced costs related to wages offered to migrant workers (Commander et al., (2002). It is important to note that research on migration has not always found positive consequences, (De Coulom and Piracha, 2005; Kupets, 2011; Sun 2013) and some have either found no difference or indeed negative consequences to migration. The literature has highlighted that this is often due to lost social connections, inefficient work experience whilst abroad, or taking work that depreciates skills (Wahba,

2015). Despite this, research has been clear that migration impacts the human capital of an individual as well as the labour markets of both host and country of origin.

When we consider the human resources aspect of migration there is an acknowledgement that occupation is influential or is influenced by the migration decision. This can be through the consideration of employment or educational opportunities, both home and abroad. Migration takes into account a perception of opportunities existing outside in comparison to more local opportunities. Migration has been argued as being the consequence of better returns for human capital acquired in a host country (Borjas and Bratsberg, 1996; Dustmann and Weiss, 2007; Lianos and Pseiridis, 2009; Piracha and Vadeans 2010). This human capital is in reference to increased knowledge, which is either practical through experience or educational via academic performance or qualifications obtained whilst abroad (Dustmann and Glitz, 2011; Kveder and Flahaux, 2013; Piracha and Vadeans, 2010). Martin and Radu (2012) highlighted the prevalence of research finding positive consequences of work experience abroad upon return, also noting the country specific nature of said research. Barcevičius and Žvalianytė (2012) also pointed that work experience abroad was considered of benefit for those whose work matched their qualification. It is important to consider, that this is not a suggestion that returned nationals are necessarily better or that there is a lack of local talent that can fill posts. What has been observed in the literature is that for a number of countries there is a preference for migrant workers over local workers particularly in developing countries, (Ambrosini et al., 2015). In addition, when looking solely at employment of migrant groups, returning migrants are not always the preferred choice (Wahba, 2015). With research in mind, there are numerous implications for human capital when considering migration. Kveder and Flahaux (2013)

Given that it is a high point of contention for political and social discussion, and considering the impact that migration has, it is important to continue research into migration in conjunction with motivating factors. We can also extend the research by looking at outcomes that may occur when considering the motivation behind such a decision.

Migration takes on many forms, it can look like the movement of people seeking refuge, family reunification, and temporary labour among other things, and having a single theory that incorporates the different perspectives has been difficult. Over time the theories have developed and have been more inclusive of different dimensions and have become less rigid. Recent reviews of theories such as those conducted by Cassarino (2004) and King (2012) have created a coherent look at the migration theories and have added to the discourse by providing key perspectives. Namely, the former focusing on the impact of motivation on the migration decision and the outcomes that may occur and the latter considering how we look at migration, whether there is merit in exploring a particular aspect of migration or in true with the nature of migration itself look at it in an interdisciplinary way.

The current study will not focus on one particular theory of migration so as not to put limitations when considering the various types of migration that may be identified by respondents. When looking at the theory from the perspective of Cassarino (2004) the motivation to migrate greatly influences many of the subsequent decisions including the occupational and behavioural choices that occur. Although the migration theories differ when considering why migration occurs, we can see that differences in the motivating factors shape the outcomes; this is the focus of the study. The current study aims to focus on the reasoning

through a particular perspective and then look at the occupational decisions made. When considering return migration King and Christou (2014) highlighted six main narratives for return, for the purpose of this review these narratives will be considered when looking at migration research. The narratives identified are: Economic rational, return to roots, way of life (life style), family narrative of return, return as escape and return related to life-stage event. In their work King and Christou (2014) also included the narrative of ‘Return as escape’ which was specific to their female sample, due to the content described; this has been combined with lifestyle.

As noted in economic theories, financial and occupational needs play a part in the decision to migrate. Mesnard (2004), noted that financial constraints in the home market was mitigated by migration, suggesting individuals could accumulate funds and return to the home country and create own ventures. This was supported by Kveder and Flahaux (2013), who noted the tendency for migration, was due to economic reasons. Dustmann and Weiss, (2007) highlighted that higher purchasing power of host currency is paramount to a return. Borjas and Bratsberg, (1996), considered reverse migration as a function of better financial gains for returnees. However, Pungas et al., (2012) noted that return tendencies were greater for those who worked below their qualifications. Borodak and Piracha, (2011) pointed to the importance that occupational choice of returning migrants has, when considering the contribution that returnees have in home country labour markets and its consequent development. They noted that returnees are more likely to be employed in comparison to non-migrants. Piracha and Vadean’s (2010) findings indicate that intention to re-migrate and reasons for the return were influential in determining occupational choice, with those considering permanent residence more likely

account who viewed it as failed, with entrepreneurs having successfully reaching migration targets. Waged employment has been shown to be the tendency for returnees of developing countries (Ilahi, 1999; McCormick and Wahba, 2001) with a note being made to returnees’ ability to seek greater wages. Also evidenced is return migration enhancing occupational mobility, returnees were able to occupy post of higher status/grading, this was dependent on the country that acted as host (Carletto and Kilic (2011). Borodak and Piracha (2011) highlighted that this was due to the influence that returnees had with respect to demanding greater wages.

King and Christou (2014) however felt that, the economic factor was overall not influential in the decision to return to Greece, with a number of their participants forgoing financial and career gains to return. For those that did see an advantage, this was in the context of moving internally within an international organisation with a presence in Greece or taking up academic posts. Bijwaard and Doeselaar (2014) also touched on this, noting that research has focused on the economic gains of reverse migration however; those returning due to family reunifications mitigated the importance on the financial motivation for return decisions. Also vital to return migration is the realization of saving goals (Borjas and Bratsberg, 1996). McKenzie and Salcedo (2009) found with over half of their sample (59%) achieving saving targets was influential in returning decisions. Borodak and Piracha (2011), highlighted that non- participation of returnees in Moldova may also be due to low wages available in home country in comparison to the saving accrued whilst working abroad as well as remittances received from family members still abroad. Despite this, returnees were more likely to be occupied, in comparison to non-migrants. Saved remittances were also a factor for non-participants of those who did not migrate. The research assessing occupational choice has been inconsistent with findings for and against a tendency for returning migrants to be self-employed versus wage

employed. This differences or lack of consistency is likely due to country specific factors for example high taxes in home country which encourages non engagement. Giving the various findings in research regarding a purely financial benefit to a migration decision, it is important to consider other factors.

King and Christou (2014) noted that the theme of returning to roots was considered influential in a decision to return. This theme was based on an emotional connection to the home country. This narrative was noted by the authors as being the most powerful despite being the most abstract. Takenaka (2014) also focused on this area, highlighting the affects that diasporic ethnic bonds has on return migration decisions. What became apparent, despite these bonds and the accompanying nostalgia, the return was not as smooth as hoped and often resulted in remigration due to failure to integrate socially and economically. It is important to note that in this research of Japanese South American Returnees, that although the ethnic bond was important another motivator was the economical one, due to policy changes in Japan affording greater opportunities for those of Japanese descent to return and contribute to the labour market.

Also noted as important to the return decision is the family perspective of return (King and Christou, 2014). Reynolds (2008) sample from Jamaica made reference to family rhetoric on the theme of returning home. Borodak and Piracha (2011) reported that for some the difficulty in being away from family influenced their return decision. Family and lifestyle was reported to have a major impact on return decisions (Gibson and McKenzie, 2011). Kveder and Flahaux (2013) also noted that a small percentage of outward migration was due to family motives.

that family was an important factor when making a return decision, with their respondents not returning, with references being made to having a family in the host country.

Lifestyle differences was also identified as a factor for return migration by King and Christou (2014), they noted that previous time in the home country be it via holidays or brief visits formed a picture of an idyllic lifestyle and reported links between this and returning as an adult. Focus here for returnees was shared family values, pace of life and social warmth. In addition to this, for female returnees from Greece, escaping parental controls in the host country was identified important. Returning home offered them a freedom that would not be available to them under the supervision of parents whilst in host country. Boyle et al., (2008) also touched on gender differences acknowledging the tendency of positive outcomes that household migration has on the man’s career, noting that woman had lower likelihood of being employed or having high income if migrating as a couple. King and Christou, 2014, also noted that for their sample, return migration also centred around certain major life events, including transition into higher education, marriage and retirement.

When considering the research and theories it is clear that there are many factors that motivate a migration decision. As noted by Rogers, (1984) motivation for return varies substantially and may also overlap. Acknowledging the importance that motivation has on the outcome of such a drastic change, the current study will consider the motivation qualities that are related to the migration decision. Extending from this, the study will also consider how these qualities interact with occupational decisions undertaken.

2.2 Self Determination Theory

As we consider the importance that motivation has on the migration decision, we will focus on the motivation literature to provide us with the theoretical framework namely, the Self Determination Theory (SDT), as described by Deci and Ryan (1985). This is an established theory supported in a range of contexts and important to this research, cross culturally supported (Gagne et al., 2015). The self determination theory proposes that motivation is intrinsic and not merely external. The theory proposes that even if external motivation occurs there are processes undertaken that transforms this into an internal motivation. There is an internalization of values and regulations transmitted by social cues. This is taken on when one is allowed to consider and support the shared views and controls. This is based on three innate needs: autonomy, competence and relatedness. Motivation is considered along a continuum, with the distinguished subtypes of motivation determined by the varying levels of internalization that exists, (Deci and Ryan, 2000a). Internalization describes how something externally regulated (goal or value driven) is transferred so that it becomes internally regulated. There is also a third category of motivation defined; amotivation, used to describe no presence of motivation. Trembley et al., (2009) noted that the self-determination model considered the quality of motivation focusing on the underscoring reason behind behaviour. This perspective is based on the idea that we have a tendency towards development and are driven by goals. This natural orientation is influenced by external factors such as environmental or social pressures which can act as a source of encouragement or suppression. Variations exist between the level and the orientation of motivation that people possess. To add to this, behaving under different reasons does result in varying outcomes in terms of experiences and performance, something that has been observed in various domains.

For SDT, motivation is considered along a continuum that extends from no motivation at all right through to internal motivation. The continuum starts at Amotivation, a lack of motivation which has no form of regulation ascribed to it. As described by the authors (Deci and Ryan, 2000) and reiterated by SDT researchers, such as Gagne et al., (2014): External regulation is the subtype of extrinsic motivation that has no internalization. Control is through external means, action is due to reward or the avoidance of a punishment by others. Introjected regulation is the subtype that follows with limited internalization. Behaviour is determined by internal means, the ego becomes involved, shame and guilt also play a part. What follows is Identified regulation which specifies activities being completed as there is a recognition of its worth or meaning and there is an acceptance of it. This form of internalization is considered volitional. This differs from intrinsic motivation, as the activity is completed for instrumental reasons; it is not being completed for the inherent satisfaction of undertaking the task. Lastly there is Internal regulation, which represents the undertaking of an activity for its own merit. As the subtypes have been found to highlight different outcomes in terms of behaviours and attitudes in numerous domains, there is an argument for having a scale that allows for insight into the different subtypes (Gagne et al., 2014).

Considering SDT we understand that there are levels of internalization present, which varies from person to person and for the activity. We are also aware that levels in internalization yields different results, we can draw parallels when considering the migration research, which suggest that there are various motivations for migration and that respective consequences occur as a result of this. The current study will use the theoretical framework set by Ryan and Deci (1985) and apply the SDT in the context of a return migration decision. The current study therefore considers the following questions:

How do the different regulation subtypes shape the way that migration decisions are made? Did these subtypes have an effect on the processes that followed?

What are the reflective themes that emerge when we consider the return migration decision? What is the consequence this has on employment decisions?

By considering these questions not only will we explore the motivation behind a return migration decision and how this may shape the occupational outcomes, we can also consider how effective SDT is as a tool in understanding the return migration decision adding another perspective to this research area.

3 Methodology 3.1 Approach

The current study is exploratory, designed to apply the SDT in the context of a return

migration decision, an area not previously covered through this perspective. The purpose is to explore the return migration decision and the underlying motivations behind the decision. Going on from this we will look at how the motivation quality may have shaped the occupational outcomes of the respondents. The study uses the Semi Structured Interview (SSI) for data collection as a means to explore participants’ perspective on their return

migration decision and also the employment considerations made. The interview was opted in direct reflection on the open questions the study addresses, the study is focused on themes that emerge as well as how this shapes processes that follow, the approach is better suited to meet the aims (Fidel, 1993) and is consistent with previous research that has looked at international migration decisions, (King and Christou, 2004; Legido-Quigley et al., 2015) as well as motivation research (Lloyd and Little, 2010; Lochner et al., 2012).

3.2 Participants and Sampling

This study used non probability sampling, the sample was not representative and entirely of convenience through direct contact and snowball recruitment. The sample was purposive given that only adults that have migrated for a minimum of 12 months were contacted to participate. Participants were recruited throughout April and May to take part in the study. The recruitment of participants was conducted as follows, to start information about the study was passed on through social media direct communication (private message, messenger) and direct face to face communication with people in investigators social network who were also asked to pass on details to people in their own social network. At this time the investigators contact details were provided for potential participants to use. Due to low response, participants were then

recruited directly via phone, text messages, messenger, and via email. Participants were also asked to indicate how they would like to be interviewed, four options were given: face to face, video conferencing, phone or email. Follow up emails and messages were sent to those that indicated interest and provided contact details but did not set up a time for interview. Three follow up messages were sent to each non-respondent in total, this was to ensure that there was a level of consistency between those that were known to the investigator and those through extended social networks. It was important that it was clear to all those contacted, that their participation was voluntary and that this would not have a consequence on their relationship with the investigator so this consistency was key. Interviews were scheduled and conducted over the course of four months June-September 2017. Participants were emailed an informed consent form and asked to reply and provide demographic information as confirmation they consented to the study.

Of those initially contacted to participate a total of 14 provided their contact details to schedule an interview. Informed consent forms were sent to all, of which seven responded. All others received a message as the first reminder. There was a second follow up message sent, of which an additional four respondents completed the consent forms and scheduled interviews. Email addresses and requests to participate were received from another two respondents, one of which completed the consent form and scheduled an interview. From the referrals of other participants two indicated interest to the investigator and consent forms were sent out. One of which was returned. To summarise, of the 18 informed consent forms sent, 13 respondents provided demographic information and agreed to be interviewed. Following the mentioned prompts a total number of 9 were interviewed, four of which were male and five female. Their ages varied

countries and made the decision to stay, two were in host countries and made the decision to return, 4 were in home countries having returned.

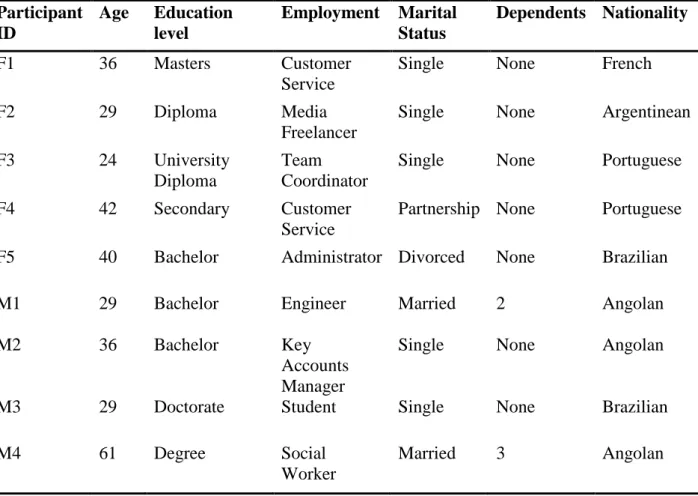

So that we have an understanding of the make-up of the sample demographic information was collected, and is outlined in table 2.

Participant ID Age Education level Employment Marital Status Dependents Nationality F1 36 Masters Customer Service

Single None French

F2 29 Diploma Media

Freelancer

Single None Argentinean

F3 24 University

Diploma

Team Coordinator

Single None Portuguese

F4 42 Secondary Customer

Service

Partnership None Portuguese

F5 40 Bachelor Administrator Divorced None Brazilian

M1 29 Bachelor Engineer Married 2 Angolan

M2 36 Bachelor Key

Accounts Manager

Single None Angolan

M3 29 Doctorate Student Single None Brazilian

M4 61 Degree Social

Worker

Married 3 Angolan

Table 1 Demographic information about sample

3.3 Materials

Demographic data was collected using the online service Google Forms, this product was deemed appropriate to create and share the informed consent form and the demographic

information as it allowed for both to be sent out to individuals directly and for responses to be collected and stored through the sites encrypted servers.

The interviews were semi-structured with a guide produced, with topics based on themes that emerged from migration literature and a SDT scale. The guide was prepared to provide probes for the 3 potential scenarios: those who had completed a return migration, those in host country who had decided to return and those in host country who had decided to stay. It was designed based on topics that emerged from migration literature and an SDT based scale.

The scale used as a source of inspiration for the current study is the Multidimensional Work Motivation Scale (Gagne et al., 2014), designed for analysis of work motivation, this scale has been translated to various languages and validated cross culturally. By using the scale to inspire the interview structure and not produce a straight adaptation of the scale from one context to another allowed for us to fully gain an understanding of participants decision making process and the impact that this had on subsequent behaviours and choices, by only adapting the scale there is the risk of limiting respondents responses, through an interview respondents are allowed to be forthcoming with their own reflections and experiences. Decision was reinforced by research that also supported the use of qualitative methods when assessing motivation, (Lochner et al., 2012) as well as research methods that included the use of interview as the first step of creating a questionnaire for research looking at the motivation in a different context (Vansteenkiste et al., 2004). The wording allowed for those currently in host country to consider what they currently do or what they would intend to do. For those that have already returned, the wording allowed for reflective responses on what they did and what was taken into consideration in preparation for the return.

As mentioned, the interview was structured with SDT in mind and the guide produced is outlined in Appendix 1. The interview session was structured as follows:

The start of the interview session is a general introduction with a brief about the study, a reminder of the terms of the informed consent and how the information would be used. We begin to explore the topic through basic questions and a clarification of the interviewees’ current situation. It is at this point where we assess amotivation (whether there is a motivation to return or not). This was followed by questions that addressed the duration of the stay and when they started to consider a return migration.

Questions that addressed research undertaken and preparation for the return came after. Here we started to include prompts that dealt with external motivation such as material influence and social regulation. Following this, there were prompts that were specific to introjected regulation and identified regulation. Participants were prompted to give an insight into their feelings regarding the move. The point was to gain as much about the personal significance of the return. Respondents were also asked to share about their occupational choices, what they were currently doing, what they considering doing in the home country. Finally, respondents were given the opportunity to share anything else about their decision to migrate, preparation or any aspects of the process. The interview closed with the interviewee being thanked and with information about what followed, essentially them receiving a transcript for review. A debrief was also provided. Interviewees were also given the opportunity to ask questions regarding the interview

The majority of the questions used were open, to illicit as much information that participants volunteered about their views and perspective on their migration decision and how they came to that decision. The questions were also used to gather information on employment seeking behaviours. Additional questions were only used to clarify a point made or to expand on an answer. Email interviews were conducted in an asynchronous way as outlined by Meho (2006), with the number of exchanges outlined to participants prior to the start of the questions so they were aware of the number of exchanges that would occur at the time when making a decision to consent to the interviews. Interviews that were conducted in person, over the phone or via video conferencing were recorded to assure accuracy when transcribed. To record the interviews for the purpose of transcribing two mobile applications were used, the first being the Voice Recorder, on the Samsung Galaxy Ace 4, the other being AudioRec on Samsung SM-T530.

3.4 Analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim, they were then reviewed and edited for clarity and the removal of repeated utterances and conversational fillers. All of the transcripts were then sent to participants for a confirmation that the transcripts were accurate. The email interview responses were put together in the form of a transcript and also sent back to respondent. Seven of the participants agreed that the transcript were accurate and no edits were made, two participants provided an edited transcript. The transcripts provided were reviewed and there were no great changes made, with only minor amendments highlighted by participants. One respondent corrected the names of cities mentioned and also edited a response where there were

Following confirmation of the transcripts, the transcripts were reviewed for familiarity with the material. Content analysis was carried out as described by Bengtsson (2016), transcripts with sections that were in direct response to questions highlighted. Sections that were of interest were also highlighted. Transcripts were reviewed again with the sections and phrases previously highlighted being allocated a theme. This was repeated for all transcripts. As the study design is inductive, the list of themes was created from the transcripts and following this all transcripts were once again reviewed and were cross referenced with the list of themes. The themes were reviewed, and then categories identified. Appendix 3 presents the coding steps undertaken with a condensed extract.

The paper applies the SDT to the context of a return migration decision the first focus is looking at the impact that a motivation type has on a return migration decision. We then go on to consider the themes that emerge when considering reflections of a migration decision. We also consider how motivation feeds into the job search activities and occupational decisions taken. We will consider the themes that emerge in line with the following areas: initial migration, return migration decision and employment considerations. The themes that emerged include impact on family, contribution and defining where is home. We will conclude with the final thoughts on respondents’ experience.

4 Results

4.1 Initial Migration and Return Decision

We will start by considering the initial migration experience and then the return migration decision. When we considered the motivation for initial migration, this varied, with the sample indicating a number of reasons for their outward migration and their initial decision to stay in the host countries. For those who moved to the British Isles (n=7) the most referenced reasoning was employment opportunities and employment variety, this was highlighted by a third of the respondents. What followed was language; this was in relation to improving and continuous development of English language skills. Two of the respondents were children when the initial move was made, and the migration was a decision undertaken by family, one respondent (M2) noted that this was due to the perception of better opportunities abroad. Like the other two respondents who moved from Angola, M2 also mentioned the effects of the civil war being a reason for migrating out specifically the socio-political climate, instability and lack of safety. Two interviewees migrated to Portugal, each with distinct reasons, one was due to continuing with higher education, and the other was due to family commitments.

When considering the return migration decision n=3 decided to remain in the host country, n=2 had decided to return and n=4 had already completed return migrations. Table 3 presents the country of origin, host country and decisions undertaken by respondents.

Origin Host Decision

F1 Surinam United Kingdom Return

F2 Argentina United Kingdom Returned

F3 Mozambique United Kingdom Returned

F4 Portuguese United Kingdom Stay

F5 Brazil United States Stay

M1 Angola Ireland Returned

M2 Angola United Kingdom Returned

M3 Brazil Portugal Return

M4 Angola United Kingdom Stay

Table 2 Summary of the origin, host and decision of interviewees

4.2 Reason behind the decision

When we consider the reasoning behind the migration decision, irrespective of the decision made, employment was the most discussed factor. It was noted as a motivator, with two of the three interviewees who decided to remain in their respective host countries acknowledged that their decision was due to the employment opportunities currently available to them with references made to their continued professional development (F4 and F5). One respondent (F4) noted that staying and the employment stability offered meant that they could help support family members back home as and when needed. It is important to note that this respondent previously returned to their home country following two years in the United Kingdom, and when they were unable to secure a job in their home country, re migrated. The other respondent who decided to stay (M4) gave their reasons as being primarily due to the socio-political climate in their home country:

“the decision is based on the situation, the instability of the country, maybe if time goes and the situation gives me more confidence that stability comes, then maybe I can decide to go”.

For the respondents who decided to return the reasoning behind the decision was as follows; employment status and opportunities was an important motivator for one (F1) who identified the job uncertainty faced due to organisational change with current employer. Comments were also made with respect to the quality of life while in the host country, noting that a balance was needed between working and enjoying life. The other interviewee (M3) noted that the inspiration for his return to contribute towards the growth of his region through a social project that he has planned and developed along with his family which he hopes to continue upon returning:

“I want to work with the communities there, helping some communities to improve their perspective of social control, aspects like economy, local education”.

Of the four who had already returned; for half of the subgroup a lack of job satisfaction and career prospects in their desired areas was a motivator for the return (F2 and M2). M2 added, that he felt that returning was the only option to be taken:

“I was in such a depressive state due to lack of self-realisation and poor prospects”.

One respondent (M1) highlighted missing country, culture and family. For F3 the return decision was something that was completely unplanned, and it came about naturally having been in Portugal for a break. The respondent described that the trip was taken due to an

“I thought I am going to take a break … I decided to come for a holiday and see how it would work out, just to clear my mind ... then I though while I am here, might as well and apply for a job and I got one straight away”.

4.3 Social Influence

With respect to social influence as a motivator, family perspective and the influence that this has had on the decision, all respondents were clear that the opinions of family and friends was not considered when making the decision. One third of respondents (F1, F2 and F3) opted to not discuss their decision with family at all and only with friends, their decision to do this was to not to give false hope as there was uncertainty about the move and the possibility of there being changes to the plan. In the case of one interviewee (F5) the decision was taken so as not to worry family about travelling and settling in a new country alone. Three of the respondents were met with mixed responses (F4, M1, M2) with some happy about the return and others more sceptical not just about the timing of the return but the integration. For another participant (F2) family and friends were very supportive and excited by the return however she noted that this was not a source of motivation as the move was primarily due to job dissatisfaction and limited prospects. What she and others found (n=3) was that family and friends were a source of information when weighing up options and researching their home country in preparation for the return. F2 did add that family support would always be an advantage when returning; noting that even if faced with limited job prospects in the home country, being in the presence of family would mitigate that. With one interviewee (M3), there is much discussion with family and while there is support and encouragement for the return, this has no influence on the decision to return, because there is a feeling of continuous interaction and communication with

family virtually and there is an understanding between him and his family the time spent abroad are steps needed in preparation to return and realise long term objectives.

4.4 Preparation

We can see the impact that both of these motivators had on the subsequent preparation for the return and the effort put into it, the most reported activity was looking for work, all but three respondents (F3, F4 and M4) included this. There were varying levels of preparation for the migration decision taken, with 1 respondent (F5) indicating that more could have been done in preparation and identified the support of those she met through her church groups as helping bridge the gap. Others (M2) felt that they had put great effort in preparation for the return including going to other countries for recruitment events. F2 added that they also prepared for the physical move itself account for their belongings being transported and M1 included preparing psychologically. This was described as starting to reach out to family so that there was more familiarity, using the internet to be up to date with trends and the local news. It is important to note that this respondent cited missing family (along with country and culture) as one of his motivators for the return decision.

4.5 Reflections

With respect to the feelings expressed there was great variation between the sample; there were feelings of hope from a number of respondents (n=4), with most hoping to stay in their respective host country (F1, F4 and F5) and one (M3) to return. Uncertainty about the future

of Britain from the European Union, F1 is also facing changes at current employer, M3 is unsure of securing a job and having to relocate and for F5 a decision on being granted right to remain in the host country. Two of the respondents (M1 and M2) highlighted their anxiety about the return however; M1 did also reflect that there was also a sense of excitement due to personal growth and was curious of others response to him given the time they have had apart. When previous visits were mentioned M2, noted that this played a part in the decision to return, as the limited time spent in the home country as a holiday meant there was a curiosity to get to know the home country. Although five of the participants stated they visited the home country, no one else felt any such impact. Another theme that emerged was that of contribution, when discussing their decision 4 respondents referred to the how they could contribute to their country of origin (one of these being M4 who has decided to stay however works in home country). Respondent F4 who decided to remain discussed this in reference to their current employer and acknowledging that this was reinforced by the positive feedback received by employers.

One aspect of migration that was reflected on the most was 'missing family'; this was acknowledged in eight interviews. When addressing emotional reflections on migration, F2 noted that: “I wouldn’t say excitement … just the thought of being near family was the nicest thing”.

M3 reflected there was an impact on both him and family due to the distance, but there was also a great effort to maintain communication and their focus on the long term plan helps with this. F3 stated:

Through this acknowledging that the period following the initial move back was not a challenge, and saw it as touristic as there was much to do and see, but after this period there was a longing for returning to the United Kingdom, and specifically “home” where immediate family were located.

The concept of home was a factor reflected on in six of the interviews. Making reference to where immediate family were located, M4 noted the United Kingdom as his home country as opposed to his birth country. F4 further stated she felt more at home in her host country, acknowledging roots in her country of origin, but describing herself as a “cultural refugee” due to feeling more comfortable in the United Kingdom in comparison to Portugal. It is important that for both of the interviewees mentioned, their stay in the United Kingdom has spanned around 20 years. For those who have dual citizenship and do not find themselves currently in their country of birth or citizens, they made distinctions between the countries acknowledging both as home but reflecting on why one would be considered home over the other, for example citing cultural differences (F1) aspects of familiarity and lost social connections (F5). Two respondents (F4 and M3) while acknowledging their home countries, touched on the idea of feeling at home everywhere, both reflect not only on feeling at home and having a global perspective, but on their openness to move again to other countries should the need arise.

Three of the respondents noted that migration to host country was not something that was permanent. F2 and F3 initially migrated out due to further studies highlighting that the intention was always to return. Participant F3 reflected that there is always a desire to return home,

“originally it was like one month ticket and one year or two … then you feel at home’’. The other side of this perspective was also experienced by F3, the return not being permanent:

“within two weeks I knew I couldn’t go back and live there, it is so difficult”.

Of the experience, what stood out were the limited opportunities in their home country, and the employment processes were not ones that were agreed with, so a decision was made to re-migrate back to a host country. M2 also saw their return as temporary, the move was seen as a way to develop professionally and build on savings. Also of interest was M4, who despite being employed in home country and working primarily from there, does not see this as a return journey, when discussing return migration, he reiterated that this is not something that he would do due to the instability of the country and was clear that his living and working there was simply the case of working in the home country.

4.6 Employment considerations

For five of the sample (F2, F4, F5, M2 and M3), comparisons were made between local job markets and that of home country. For 2 (F2 and M2) there was an awareness of lack of local opportunities in desired professional area. Three participants considered only one job market, not as a comparison as they had already decided to move (F1, M1) or in the case of F3 who had already returned, and wanted to see what was available. M4 did not consider the job opportunities available.

Four of the sample, (F1, F4, M1 and M3) highlighted an understanding on their human capital and reflected on the return they expected. F1 acknowledged their language skills and

experience would allow for greater returns when in home country. F4 expected that the skills gained overseas would be advantageous once back in their home country, a thought shared by M3, who has made plans for the immediate future to gain as much experience before returning. M1 also acknowledged this, noting that the jobs considered were in direct relation to his studies; nothing else was considered due to his area of studies being highly sought after.

When looking at the jobs considered, for all those interviewed four focused on jobs that were in line with their current experience and areas of study (F1, F5, M3 and M4). The roles they undertook complimented their studies and they only focused on jobs in line with this. Of these four, one (F1) noted that they were also looking to set up their own business venture in a different area and if things progressed as intended they would transition into this new area completely. Of the other participants, two noted that they considered and preferred roles in their area of studies, however were open to other opportunities in line with their experience in a different area if it meant employment (F2 and M2). One interviewee (F3) focused only on roles related to work experience and the other (F4) was entirely flexible and open to all job opportunities. M1 only considered roles that were related to his area of study. All of the respondents who returned and wanted to work in a particular area reported they are currently working in their preferred area.

In terms of job search activities, five of the participants acknowledged that their approach was the same when considering jobs in host and home country. What was common was using websites; the most used were sites that announced jobs from various companies as opposed to

had previously returned to the home country as was the case for M1. Although the same activities were undertaken, one participant (F4) added they also had to go through the job centre and sign on as unemployed which was something she was not pleased with:

“first you had to register through the job centre, which was something that I really did not want to do, as I was quite young and full of vitality, I never wanted to register as unemployed. I wanted to do something I wanted to work”.

Three participants noted differences, two (M3 and M4) stated that as they already had a career in their home country, when it came to seeking employment they could rely on their social connections. M3 acknowledged this was something he could not do when looking for employment in host country and described the process of building his CV in a social way in the host country:

“I am trying to develop all of this, building some kind of network … I have a community online for investigators or researchers in communication sciences and now we are sharing activities, that we are producing and every time I am going to conferences they see me and the community is always sharing”.

M4 specified that for him it was a case of contacting his former employer who was happy for him to return. M2 described the use of agencies specialising in finding educated and experienced migrants for posts in Africa. This process included uploading of a C.V for screening and being invited to forums and career events for interviews.

5 Discussion

The study outlined implemented the SDT theory in research looking at a return migration decision. The aim of considering migration under this perspective was to have a more in depth of look at the motivation behind a migration decision, this was considered important due to the research in migration and theories on migration highlighting the importance of motivation to migrate on its outcomes (Kveder and Flahuax, 2013; Cassarino, 2004). When we consider the impact that the different motivation types have on the reverse migration decision we can see that one of the most mentioned motivations was employment, and that this directly shaped the preparation undertaken by respondents, with most of the sample undertaking research on work options, benchmarking their potential salaries and actively looking for work. This is in line with previous research that has considered the economic influence of a migration decision. As noted by researchers including Piracha and Vadeans (2010), the human capital of the respondents was something that was considered, with a number acknowledging that skills gained in host country would secure them either better employment or financial reward in their home countries, which is similar to what Veder and Flahaux (2013) acknowledged. When we consider the motivation and the effects on employment decisions we can see, certain patterns emerge from the results. From our sample we see that for most, employment opportunities is a big motivator for the decision, regardless of the decision made (to stay, return and for those who did return). What we can also see in those that returned, the main preparation undertaken was to at least look at the job market and if possible secure a job, often this was initiated while in the host country. They put effort in seeking as much information as possible including using their social network as source of information. For those returning to developing countries, the reasoning was clear, poor infrastructure and wishing to secure a job, something which is in line

particular area, reported they were working in their preferred areas. In terms of the type of jobs considered, the sample were very clear about the jobs that they wished to undertake and some went on to even suggest specific roles that they were willing to undertake. Only two respondents were flexible, one of which was due to being in the host country for a short duration and wishing to settle. While employment was a key motivator, it is important to note that it was not seen as exclusively as an economic motivator, while some of the sample acknowledge the financial impact of employments and the rewards they could associate with having a particular employment, it was not always a financial payoff for the respondents. Employment was something that was also internalized by our sample, something which too is supported in research looking at work motivation.

With respect to social regulators, specifically the influence of family and friends this was not considered a motivator, with the majority of respondents not considering the family input when making a decision; some respondents went as far as to not discuss their decision with their families at all. What is important to note is that friends were seen by some as a source of information for the return, and helped prepare and provide insight into local job markets. Migration literature, often finds that family acts as a motivator for a research decision (Borodak and Piracha, 2011; King and Christou, 2014; Reynolds, 2008) especially given the impact that the migration decision has on family. While the impact was acknowledged by the respondents, for the current sample, the decision was one that was mainly taken without family input or opinion in mind. It is a possibility that for the current sample, given that the main motivator was employment, family influence may not have been considered due to the economic support that respondents could provide to family. Migration research has often mentioned the important that savings and remittances has on the migration decision given the impact this has in supporting family among others (Byron and Condon, 2012; Easterly and Nyarko, 2008;

McKenzie and Salcedo, 2009; Takenaka, 2014). One would not be amiss to consider that although not explicitly stated by all, this may have something to play with the decision. It is also important to note that the majority of respondents also do not have children and are not married (2 were married and had children), we are aware through research conducted by Legido-Quigley et al., (2015) among others that this also impacts the migration decision.

With respect to introjected, identified and integrated regulation the picture is a lot less clear. While we can see that there are aspects of the return migration decision which has been internalised, however, making concrete distinctions on exactly where on the continuum respondents lie is difficult. While there were expressions of feelings of contribution, excitement and positive feelings about the decision and experience, distinguishing between the roles these regulations played in the decision was difficult as they were not mentioned in the context of being motivators. There was recognition of these feelings being involved, with only two clearly defining this as motivators, none of the other participants outright mentioned any of these as motivators, or suggested that they were anything other than a reaction to the situation. The closest acknowledgment that we had was contribution, which given the context would be considered as identified regulation (relates to finding worth and meaning, Ryan and Deci, 2000), this was mentioned in the context of being able to contribute, as well as a feeling of currently contributing. Internal regulation such as excitement and a curiosity was mentioned overall in passing, so it was not as a motivator but mainly a reaction to the situation. The other thing to remember is that the return migration decision was for the majority of the sample something that was linked greatly to employment; while employment has external benefits not all of the responses suggested that employment was purely externally motivated. This being

would be beneficial to extend the work done in current research to further assess the internalization in this context, it would be important to assess SDT in both the migration decision and on the biggest motivator such as employment, to account for overarching influence. The interview style being open resulted in themes and phrases that can be considered in the future when assessing migration motivation under the perspective of SDT, using the current output would mean that we can consider themes that are more relevant to this area and creating or adapting a scale that could better consider the different motivation domains.

When we consider the themes that emerged, they included ones that have been previously seen in other research such as employment opportunities and career progression; as well as others not seen such as independent decision making and uncertainty of decision. As noted by Rogers, (1984) the reasoning behind the decision varies, and like the research that has come before which looks at return migration, they interact. What was different in this study in comparison to others, was that there was limited social influence to the return decision. While respondents did recognise that they missed family or reflected on the impact that distance had on the family, the decision was not taken with family in mind. There were a number of those interviewed who did not even engage family in discussion regarding their decision. It would be beneficial to look into this further; as the sample size is small, it is not clear whether this is simply an effect of that.

When looking at the themes a thing to note is the concept of home, throughout the study this themed emerged naturally given the nature of the topic at hand, and contrary to migration literature that typically defines home (be it explicitly as country of birth or by focusing on migrants to and from a specific country) a decision was made by the researcher to not define home. By not having a fixed definition, the respondents were allowed to define where they

thought their home country was, and as noted there was clearly a difference in both the migration decision and motivation factors when distinctions were made between the different home countries. Given that migration can involve stops in multiple destinations and therefore multiple places can be considered as a home country, it would be of interesting to see if these differences between job seeking strategies would be observed on a larger scale.

One thing that was clear in a number of interviews was the level of uncertainty regarding their decision, while they were fixed with respect to the employment that was under consideration, what was more inconsistent was the actual decision to migrate. As noted, there were external factors that some of the interviewees were entirely dependent on, for example change in regulations because of Great Britain leaving the European Union and not being granted the right to remain. This meant despite their decision, there could be instances in the future where there would be forced migration either to their home country or to another country altogether, it would be of interest to see how this would shape the continued preparation and ultimately employment options considered under these circumstances and how this would vary with current attitudes and job seeking behaviours.

As well as continuing to explore migration through a perspective like SDT, what would be a natural step further for studies that consider motivation in a migration decision, is to follow participants in the long run, not only to see whether the participants intentions had played out, but to also see how this occurs. In this study we were able to allow for those who had completed a return journey to reflect back on their experience and preparation, but the area would benefit from following participants through the varying stages. Although this comes with its own

a result of this, and then see how this is impacted by other factors and the adaptation that follows.

When considering the current study, what stands out is the sample size even considering that qualitative research does not often entail the same numbers that is found in a quantitative study, the sample size is limited. Although effort was made to secure more participants, the sample was purely of convenience stemming from social contacts and referrals. It was important that participants were allowed to make a decision on whether or not they wished to take part, and despite the prompts given to those who did respond and indicate not only interest but also initially consented and completed demographic information, their decision to no longer engage with the study was respected. What would be beneficial in the future is to expand on the pool of potential participants, by communicating with local organisations that have engagement with migrants. They would be able to recommend the best ways to reach a greater range of potential respondents and would also diversify the respondents, which would allow for much richer analysis.

6 Conclusion

The current study intended to add to the literature on reverse migration by seeing migration decisions under a different perspective. The study considered the practical application of using SDT in the context of a reverse migration decision, the themes that emerged as a result of this application were considered and to conclude, the occupational impact was pondered. The Self-determination Theory frames behaviour in a way that accounts for the intrinsic and extrinsic processes behind it. Not exclusively as binary forces that influences behaviour, SDT considers how internalised a particular area is and from that we can consider its influence. While the theory has been applied in a number of areas including education, health behaviours and even in occupational settings, by applying SDT in the context of a return migration decision we were able to shift the perspective of migration studies by considering motivation in such a particular way; by considering the emerging themes and consequently explore the impact on occupational outcomes. The themes that emerged by looking at the return migration decision in this way included the influence of employment, independent decision making, the use of social network as research on employment opportunities and the concept of home. We also can make inferences about the internalisation of the migration decision for this sample.

When looking at the overall findings, we can see that the migration decision itself has been internalised, there is a clear tone set by the respondents that their reason for return is not purely external. Respondents have given insight into the feelings surrounding the move, and what they hope to gain by the move and although the financial benefits were clear for some, there were also mentions of more internal regulators such as feelings of contribution towards their home

exclusively externally regulated. While for some there were mentions of financial gain, it is clear that aspects of employment were also internalised. With respect to occupational choices, respondents were very much aware of their human capital. Not only did they reflect on what they had to offer but they also had an idea on its value. There was a focus on seeking employment congruent with experience and or studies, and mentions of employment outside of this were due to circumstance. What would be beneficial when looking in this area in the future is to further assess the level of internalisation of both the migration decision and the employment decision, giving us an exact indication on where on the continuum both lie and then seeing how they interact with each other and the subsequent preparation taken. The research on motivation is clear; the more internalized the better the outcome or the tendency to undertake an activity well, by having an idea on the internalization of such a decision can help with forecasting not only in the local sense for projecting by talent sourcing and management but also consider the impact on wider trends or catalysts where there is a potential for mass migration.

It was clear that the motivation behind the move influenced the preparation that was undertaken and the things that participants considered after making a migration decision. We can see that in terms of preparation for the move, employment was the biggest focus be it comparing job markets, setting wage expectations and also securing work, this appears intuitive given the part that employment played on the migration decision. What was also of great interest with this is the use of social networks to inform employment options and decisions and how it fed into the preparation. As an external regulator, social network was not as influential on the migration decision unlike previous research, however, for the respondents’ social network proved invaluable as a resource for planning and preparation for the move. Given the rise in the use of