1 CHAPTER 20

Life Cycle of Wine Routes:

North Portugal’s Perspective

Darko Dimitrovski, Susana Rachão and Veronika Joukes

IntroductIon

Wine routes can be an important tourism product in a wine destination, enabling the promotion of its distinctive characteristics, as they have the strength to boost tourism, increase competitiveness, secure sustainability and profile the destination as unique (Bregoli, Hingley, Del Chiappa, & Sodano, 2016; Bruwer, 2003). As wine routes are dynamic systems, their success is closely related to the roles and attitudes of both their coor-dinating body and members (Brás, Costa, & Buhalis, 2010; Brunori & Rossi, 2000; Hashimoto & Telfer, 2003).

© The Author(s) 2019

M. Sigala and R. N. S. Robinson (eds.),

Wine Tourism Destination Management and Marketing,

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00437-8_20 D. Dimitrovski (*)

University of Kragujevac, Kragujevac, Portugal e-mail: darko.dimitrovski@kg.ac.rs

D. Dimitrovski · V. Joukes

University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro (UTAD), Vila Real, Portugal

S. Rachão

INNOVINE & WINE Project,

University of Trás-os-Montes and Alto Douro, Vila Real, Portugal e-mail: susanarachao@ua.pt; susanr@utad.pt

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 A1 A2 A3 A4 A5 A6 A7 A8 A9 A10 AQ1

The ‘product life cycle’ (PLC) model of Levitt (1965) helps us to understand the unique characteristics of each life cycle stage. Using this model in analysing wine routes helps us to gain a better understanding of the ongoing process of change. Wine routes are tourism products and thus they pass through a life cycle (da Conceição Gonçalves & Águas, 1997; Dodd & Beverland, 2001). This study analyses the dynamics of Portuguese wine routes with a special focus on northern Portugal.

t

heh

IstoryofP

ortugueseW

Iner

outesIn the European Union, Portugal is ranked fourth in terms of the larg-est percentage (6%) of its territory planted with vines after Spain (30%), France (25%) and Italy (19%) (Eurostat, 2017). This is the result of his-toric practices.

Nowadays, Portuguese wines are the centre of attention, among other reasons, because they are prize winners in international contests and increasingly wine tourists want to try out these wines in their own terroir. Wine tourism is becoming an interesting niche market, with one of its potential top products being 16 regional wine routes. This hasn’t always been the case, as Portugal only became democratic after a peaceful revolution against the dictatorship in 1974 and gained European mem-bership in 1986. Although Portugal has always been a country blessed with thousands of very small to extensive vineyards, with the exception of Port wine, it has only been since the nineties that the quality of the wines produced all over the country has improved considerably and that ever more attention has been paid to wine tourism in Portugal.

After the entrance of Portugal to the European Union, two impor-tant orientating documents, the Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.° 17-B/86, which in 1986 approved the first strategic plan for tourism after the revolution, and the Livro Branco do Turismo (DGT, 1991), published by the Ministry of Commerce and Tourism in 1991, did not even mention the term ‘wine tourism’. One of the elements that inspired Portugal to invest more in wine tourism was its participation in the European Union’s Dyonisos programme, launched in 1993 to encour-age cooperation between different European wine-producing regions. Over two million euros were distributed among the partners, which included Alentejo, Andalusia, Catalonia, Sicily, Lombardy, Burgundy, Poitou-Charentes, Corse and Languedoc-Roussillon. There were sev-eral objectives: the promotion of poor wine-producing regions through

14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 AQ2 AQ3

the stimulation of their viticulture, the exploitation of expert knowl-edge, the promotion of wine tourism, the development of wine routes, the creation of quality services and the promotion of marketing activities (Simões, 2008; Zsuzsanna, 2012).

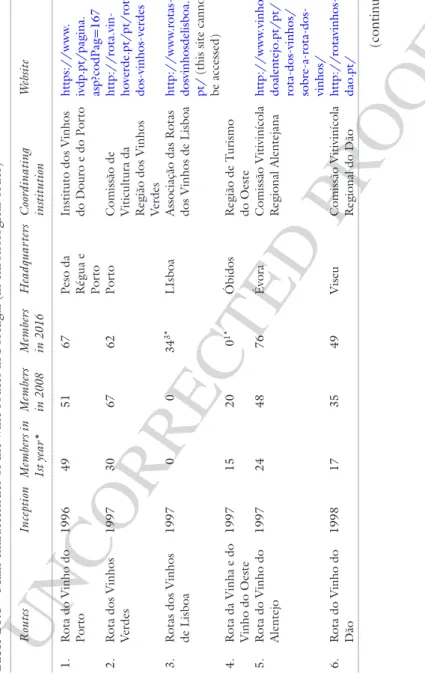

This Inter-regional Cooperation Programme provoked the publication of the Despacho Normativo n.° 669/94, a national government regulation that provided financial support for those willing to invest in wine tour-ism. It successfully prompted a number of wine regions in Portugal to create wine routes (Correia, Ascenção, & Charters, 2004) as can be seen in Table 20.3 at the end of the chapter in which the Portuguese wine routes are listed in chronological order.

It took until the Plano Estratégico Nacional de Turismo (Turismo de Portugal, 2007) to witness a formal change in paradigm. Among the ten strategic products, Portugal has to invest in over the next five years, the category ‘gastronomy and wines’ appears.

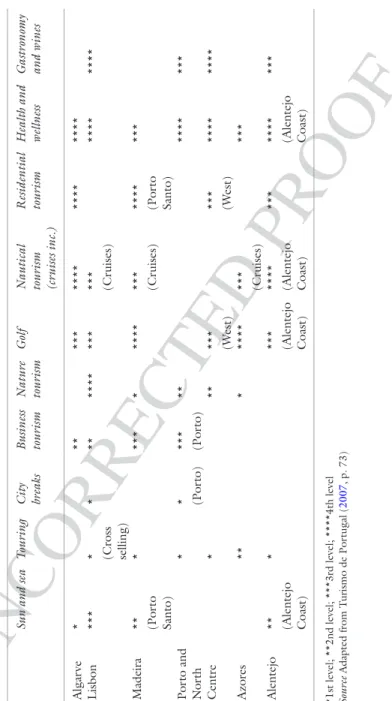

Table 20.1 clearly shows that the product ‘gastronomy and wines’ is present in the typical wine-producing regions on the continent, although in general terms it is of less importance (Turismo de Portugal, 2007, p. 73). In the accompanying detailed guide Gastronomia e vinhos on how to implement this new product, priority is given to the development of wine tourism in the north of Portugal (THR, 2006, p. 54) and the Port Wine Route is mentioned in particular: it should function better to enhance the quality and the quantity of the (wine) tourism services offered by local companies.

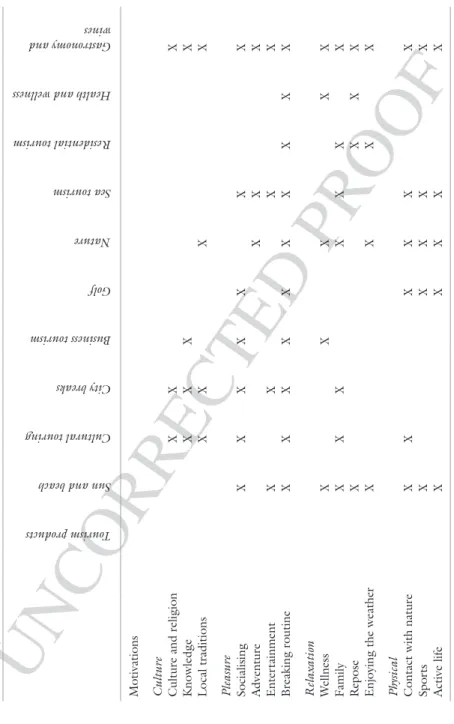

In 2015, the prevailing national strategic plan for tourism was pre-sented with a new approach to the strategic products: they should no longer be an orientating element, nor should all decisions be centralised in Lisbon. Full attention should be paid to the motivations and experi-ences of the tourists and to please them, the so-called strategic tourism products could henceforward be complemented or even substituted by other (new) products (Turismo de Portugal, 2015, p. 59).

What is of immediate note in Table 20.2 is the fact that ‘gastronomy and wines’ have been upgraded to a position in which they are seen as a possible extra for whichever type of tourist enters the country. Although ‘gastronomy and wines’ are not a primary motivation for travel, this item is assumed to be an essential complement to all tourism products. The text continues as follows: ‘In fact, gastronomy, as well as Portuguese wines, has demonstrated an enormous capacity to please and surprise those who visit us. The numerous international awards and, above all,

51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89

T

able

20.1

Contribution of the strategic pr

oducts for each r

egion *1st level; **2nd level; ***3r d level; ****4th level Sour ce Adapted fr om T urismo de Por tugal ( 2007 , p. 73)

Sun and sea

Touring City breaks Business tourism Natur e tourism Golf

Nautical tourism (cruises inc.) Residential tourism Health and wellness Gastronomy and wines

Algar ve * ** *** **** **** **** Lisbon *** * (Cr oss selling) * ** **** *** *** (Cr uises) **** **** Madeira ** (Por to Santo) * *** * **** *** (Cr uises) **** (Por to Santo) *** Por to and Nor th * * (Por to) *** (Por to) ** **** *** Centr e * ** *** (West) *** (West) **** **** Azor es ** * **** *** (Cr uises) *** Alentejo ** (Alentejo Coast) * *** (Alentejo Coast) **** (Alentejo Coast) *** **** (Alentejo Coast) ***

T

able

20.2

Matrix of motivations versus attractions

Sour ce T urismo de Por tugal ( 2015 , p. 59) Tourism products Sun and beach

Cultural touring City breaks Business tourism Golf Nature Sea tourism Residential tourism Health and wellness Gastronomy and wines Motivations Cultur e Cultur e and r eligion X X X Knowledge X X X X Local traditions X X X X Pleasur e Socialising X X X X X X X Adventur e X X X Enter tainment X X X X Br eaking r outine X X X X X X X X X X Relaxation Wellness X X X X X Family X X X X X X X Repose X X X X

Enjoying the weather

X

X

X

X

Physical Contact with natur

e X X X X X X Spor ts X X X X X Active life X X X X X

T

able

20.3

Main characteristics of the wine r

outes in Por tugal (in chr onological or der) Routes Inception Members in 1st year* Members in 2008 Members in 2016 Headquar ters Coor dinating institution W ebsite 1. Rota do V inho do Por to 1996 49 51 67

Peso da Régua e Por

to Instituto dos V inhos do Dour o e do Por to https://www . ivdp.pt/pagina. asp?codPag = 167 2. Rota dos V inhos V er des 1997 30 67 62 Por to

Comissão de Viticultura da Região dos V

inhos V er des http://r ota.vin -hover de.pt/pt/r ota-dos-vinhos-ver des 3. Rotas dos V inhos de Lisboa 1997 0 0 34 3* LIsboa

Associação das Rotas dos V

inhos de Lisboa http://www .r otas -dosvinhosdelisboa. pt/

(this site cannot

be accessed) 4. Rota da V inha e do V inho do Oeste 1997 15 20 0 1* Óbidos Região de T urismo do Oeste 5. Rota do V inho do Alentejo 1997 24 48 76 Évora Comissão V itivinícola Regional Alentejana http://www .vinhos

-doalentejo.pt/pt/ rota-dos-vinhos/ sobr

e-a-r ota-dos-vinhos/ 6. Rota do V inho do Dão 1998 17 35 49 V iseu Comissão V itivinícola Regional do Dão http://r otavinhos -dao.pt/ (continued)

Routes Inception Members in 1st year* Members in 2008 Members in 2016 Headquar ters Coor dinating institution W ebsite 7. Rota da V inha e do V inho do Ribatejo = Rota dos V inhos do T ejo 1998 24 24 26 Santar ém

Associação da Rota dos V

inhos do T ejo http://www .cvr tejo. pt/r ota-dos-vinhos-do-tejo 8. Rota das V inhas de Cister 1999 6 13 9 Moimenta da Beira Comissão V itivinícola Regional Távora-V ar osa http://www .cvr ta -vora-var osa.pt/r ota. asp 9. Rota da V inha da Beira Interior a) 11 20 21 Guar da Comissão V itivinícola da Beira Interior http://www .cvrbi. pt/index.php/ rota-turistica 10. Rota do V inho da Bair rada

Rota da Associação da Rota da Bair

rada 1999 2006 23 30 17 T amengos

Associação da Rota da Bair

rada http://www .cvrbi. pt/index.php/ rota-turistica 11. Rota do V inho da Costa Azul = Rota dos V inhos da Península de Setúbal 2000 9 9 25 Palmela

Associação da Rota dos V

inhos da Península de Setúbal http://www .r otavin -hospsetubal.com T able 20.3 (continued) (continued) AQ4

Routes Inception Members in 1st year* Members in 2008 Members in 2016 Headquar ters Coor dinating institution W ebsite 12. Rota dos V inhos de Bucelas, Car cavelos e Colar es 2003 4 4 2 Oeiras Municípios de Lour es, Cascais, Oeiras e Sintra http://www .cm-oe -iras.pt 13. Rota do V inho V er de do Alvarinho 2007 0 0 Melgaço

Câmara Municipal de Melgaço

http://www .cm-mel -gaco.pt 14. Rota dos V inhos do Algar ve 2014 0 0 21 Lagoa

Associação da Rota dos V

inhos do Algar ve http://www .r otados -vinhosdoalgar ve.pt (blog) 15. Rota dos V inhos da Ilha do Pico 2016 0 0 5 Hor ta

Associação para o Desenvolvimento Local da Ilha dos Açor

es (Adeliaçor) http://www .adelia -cor .or g/ 16. Rota do V inho da Madeira 2017 0 0 5 4* Funchal

Not yet defined

http://www .agr one -gocios.eu/noticias/ rota-do-vinho-da-ma -deira-em-mar cha/ 17.

Rota dos vinhos de Trás-os-Montes

2017

0

0

0

4*

Not yet defined

Comissão V itivinícola Regional de Trás-os-Montes? http://cvr tm.pt/? T otal 212 321 419 T able 20.3 (continued) Notes 1*(Until 2003); 2*does not exist in 2017; 3*new launch in 2014; 4*in 2017, yet to be cr eated for mally Sour ces Simões ( 2008

), Novais and Antunes (

2009

), and IDTOUR (

2016

the opinion expressed by the tourists in successive surveys of satisfaction, confirm that the combination of gastronomy and wines is one of the strongest factors of the valorisation of Portugal as an attractive tourism destination’ (Turismo de Portugal, 2015, p. 105).

In short, today’s national tourism plan foresees wine tourism as an interesting complement for other types of tourism and considers routes in general to be interesting tools for attracting visitors. However, ‘wine routes’ are not mentioned specifically in this document.

Table 20.3 shows, inter alia, that the Port Wine Route was the first to be created in 1996 and that the most recent wine route was created in the Azores two decades later. The dates in Table 20.3 demonstrate that wine tourism in Portugal is in its infancy; nevertheless, recent years have seen significant developments, such as constant investment of more money and energy in the creation and maintenance of wine routes. At the national level, the wine routes are now organised in the Association of Wine Routes in Portugal (ARVP), which recently ordered a strate-gic plan for the consultancy unit IDTOUR (2016). They concentrate on 14 routes and we have added two more routes, Madeira and Trás-os-Montes, as we discovered that there are stakeholders interested in their creation. The wine regions of northern Portugal are highlighted in Table 20.3.

t

heP

roductL

Ifec

ycLeThe product life cycle (PLC) has had a central place in marketing theory and practice for decades (Gardner, 1987). This marketing concept arose as a result of supply and demand forces (Golder and Tellis, 2004), sug-gesting differences in sales and growth over a product’s life (Levitt, 1965). Thus, Levitt (1965) introduced the concept of the PLC as an instrument of competitive power. This concept has gained huge interest due to the relevance of the biological analogy of birth, growth, maturity and decline (Day, 1981) and its evident simplicity and reality (Gardner, 1987). The identification of the stage in the life cycle is useful as it enhances strategic thinking related to a product policy (Polli & Cook, 1969).

Over time, numerous authors have confirmed the significance of the PLC. Hofer and Schendel (1978), Rink and Swan (1979) and Day (1981) identified it as an important variable in determining an appropri-ate business strappropri-ategy, while Biggadike (1981) emphasised the contribu-tion of the concept in strategic management. However, the PLC has also

90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126

raised many concerns. The general argument is that the PLC has descrip-tive value, with rather limited prescripdescrip-tive importance (Gardner, 1987). Its simplicity makes it vulnerable to criticism, especially its capacity as a predictive model for anticipating a stage change within the life cycle (Gardner, 1987) or as a normative model proposing alternative strategies for each life cycle stage (Day, 1981).

The main characteristic of the PLC is that products move through dif-ferent life phases (introduction, growth, maturity and decline) at vary-ing speeds, with profit increasvary-ing in the growth phase and declinvary-ing in the maturity phase due to strong competitiveness. Thus, appropriate product exploitation is needed to drive the product through the process (Gardner, 1987; Patton, 1959). Hofer (1975) established that significant changes in business strategy occur during the three major stages of the life cycle (introduction, maturity and decline).

In the tourism literature, the PLC is mostly associated with the Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC), as it was introduced almost 40 years ago by Butler (1980) or the tourism destination life cycle (Komppula, Hakulinen, & Saraniemi, 2010). However, we propose to discuss the life cycle of a specific tourism product. Tourism products have already been examined at the level of hotels, resorts and niche tourism products, including wine regions, but not at the level of wine routes. A wine route as a tourism product is not just the itinerary itself, interlinking all the wineries, hotels and attractions, but also includes tourists and their experiences as a part of the product production process. Increasing value is added to the tourism product at each stage of the production, with the consumers as an integral part of this tourism production process (Smith, 1994).

Taking into account that the PLC has only limited strength when it is used as a planning tool and little predictive power, our main effort is to determine the current reality of wine routes in northern Portugal and position them on the PLC curve, mainly to gain valuable insight into the current wine route dynamics as perceived by the main actors and as a useful tool to benchmark their development with other wine routes in Portugal in order to measure their competitive power (Levitt, 1965).

M

ethodoLogyandr

esearchc

ontextThe wine routes of Vinho Verde (in the Minho region), Port wine (in the Douro region) and Trás-os-Montes were selected because they are located in the three wine regions of northern Portugal, each being

127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 AQ5

characterised by a different set of attributes and level of development. Indeed, the Douro region, which stretches out east/west along the river with the same name, has a very strong and established wine iden-tity, while Trás-os-Montes, a mountainous interior region in the north-east, is better established as an agriculture/farming region and has been trying more recently to develop a wine identity. Finally, Vinho Verde is a progressive and still developing wine region in which a new sub-area, Alvarinho, has arisen where two municipalities, Melgaço and Monção, in the extreme north-west of the country, promote the same sparkling white wine. The differences between the three wine regions are a good starting point for a better understanding of similarities and differences among wine routes and their development. This approach might be repeated for the examination of wine routes in other regions.

Based on their performance in the tourism market, the wine routes of northern Portugal have been positioned as products on the PLC based on the results of in-depth interviews with the most prominent actors, mostly with leading positions within the leading wine route bodies. This approach was adopted in view of the criticism of Papatheodorou (2004) that more attention should be paid to the key individuals in the shap-ing of the tourism development process in relation to the PLC con-cept, thus contributing to earlier findings (Russell, 2005; Russell & Faulkner, 1999). The data obtained were then compared and contrasted with the literature on the PLC in tourism and wine tourism more specifi-cally (Dodd & Beverland, 2001).

This is a rather innovative approach as products are usually assessed through sales. Such a unique approach allows insight into the prod-uct reality as it includes analysis of both the internal (within the control of the wine route and its leading body) and external (outside of their control) factors that are of importance for product evolution as dif-ferent threats are encountered. Although increased sales should lead directly to the growth stage, due to organisational malfunctioning, poor collaboration and ignoring the need for innovation, a product can just as readily dive into the decline phase and simply get out-marketed.

In this research, convenience sampling was used as it conveniently uses persons from organisations (Veal, 2006) related to the wine routes. The participants were selected based on their involvement in the wine route, from former presidents to individual members. The interviews were booked by telephone and/or email and done at the office of each interviewee. 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202

An interview protocol was used in order to follow standard proce-dures in all interviews. All the interviews were tape-recorded and sup-ported, whenever necessary, with handwritten notes. The interviews had an average duration of 90 minutes. Once the interviews were transcribed, the analysis of the textual data was performed in a systematic process through a relational analysis since it allows the identification of mean-ingful relationships between concepts (Altinay & Paraskevas, 2008). The sample consisted of nine participants equally divided for each wine route. The interviewees had different roles and coverage (national or local) in the wine region. Actors from the public and private sectors and non-profit associations were included in the sample, as shown in Table 20.4. NVivo 11 Pro software package was used to perform the relational analy-sis of the interviews’ content as well as to code the themes.

d

IscussIonCombining in-depth interviews with a thorough literature review, a number of theoretical and practical implications arose. We first comment on the main outcomes per wine route and conclude with two graphs of the PLC curve: one showing the distribution along the curve of the wine routes of northern Portugal and another showing all Portuguese wine Table 20.4 Outline of participants for qualitative research

Source Authors’ own elaboration

Wine region Wine route Type of respondent Workplace Sector Sample (n = 9)

Policymaker (1) Regional level Public 1

Trás-os-Montes Trás-os-Montes Association (2) Local level Non-profit 1

Wine producer (3) Local level Private 1

Route’s former

president (4) Local level Non-profit 1

Douro and

Porto Port Route’s former director (5) Local level Non-profit 1

Policymaker (6) Regional level Public 1

Policymaker (7) Regional level Public 1

Vinho Verde Vinho Verde &

Alvarinho Policymaker (8) Regional level Public 1

Hospitality

services (9) Local level Private 1

203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 213 214 215 216 217 218 219 220 221

routes. These graphs illustrate in the blink of an eye the different stages of development of all the routes.

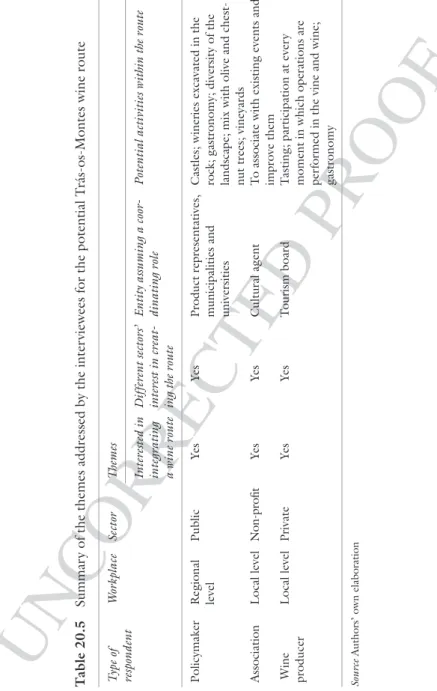

Trás-os-Montes is still a non-functional wine route, but with a strong desire among some of its main actors, as expressed during the inter-views, to introduce and establish a wine route in that territory. To posi-tion this non-funcposi-tional wine route in the PLC, we have used Golder and Tellis’ (2004) argument that the introduction stage of the PLC con-siders the period from the very first commercialisation of a new prod-uct until its take-off. Therefore, despite the fact that the Trás-os-Montes wine route has not yet been officially created and is not yet offered directly to tourists, a few steps have already been implemented to prepare for its commercialisation and therefore we affirm that this wine route is in the introduction stage of the PLC.

The three interviewees showed interest in joining a wine route being of the view that the remaining players in the territory would find an opportunity to expand their brands. When respondents were asked which institution or firm should be leading the wine route, the answers were disparate. The policymaker, for example, was the only one who believed in combined leadership to manage the route: business actors, city councils and even the local/regional universities should collaborate (Table 20.5).

Considering the potential activities that the route could offer, gas-tronomy was seen as an important factor in spreading the local culture, as well as ‘touring’ activities, thanks to the diversity of the natural land-scape. However, one of the respondents commented that there were already too many events and that the potential route should be linked to existing routes to improve them both in terms of quality and in terms of reputation and image (Table 20.5).

With regard to the Port Wine Route, the researchers have witnessed its failure. By constraining the wine route strictly to Port wine, numer-ous wine companies that have increasingly being investing in technol-ogies to produce quality still wines were excluded. Although product concentration can encourage the destination’s competitiveness, there are inevitable and obvious risks in focusing only on one or a few prod-ucts (Benur & Bramwell, 2015). Tooman (1997) sees decline as a result of excessive external stress on the physical or social dimensions of the region, such as business fluctuations, fads, prices of substitute locations or pastimes. The rupture of the Port Wine Route coincided with the worldwide financial crisis and suffered its consequences:

222 223 224 225 226 227 228 229 230 231 232 233 234 235 236 237 238 239 240 241 242 243 244 245 246 247 248 249 250 251 252 253 254 255 256 257 258 259 260

T

able

20.5

Summar

y of the themes addr

essed by the inter

viewees for the potential T

rás-os-Montes wine r

oute

Sour

ce

Authors’ own elaboration

T ype of respondent W orkplace Sector Themes Inter ested in

integrating a wine route

Dif fer ent sectors’ inter est in cr eat

-ing the route

Entity assuming a coor

-dinating role

Potential activities within the route

Policymaker Regional level Public Ye s Ye s Pr oduct r epr esentatives,

municipalities and universities

Castles; wineries excavated in the rock; gastr

onomy; diversity of the

landscape; mix with olive and chest

-nut tr ees; vineyar ds Association Local level Non-pr ofit Ye s Ye s Cultural agent T

o associate with existing events and impr

ove them W ine pr oducer Local level Private Ye s Ye s T ourism boar d T asting; par ticipation at ever y

moment in which operations ar

e

per

for

med in the vine and wine;

gastr

At some point between the members begins that point of envy […]. If there had been unity and strong common interests, because – if you look at the facts with some distance – some members did not want to subordi-nate, but to dominate […], and then the crisis appears. (Interviewee 4) The Port Wine Route comprised important but limited activity. It had its own space, open to the public, welcoming and guiding 10,000 to 11,000 visitors a year to different activities and making hotel, restaurant and cruise bookings. At the same time, it served as a platform for selling the products of its adherents. (Interviewee 5)

When the route had to redefine its management, the new leading team understood that the route should be more active, engaging in high-value community projects:

They allowed the growth of the media visibility of the route. Nevertheless, this promotion was more focused on the region as a tourism destination and less on the promotion of its adherents. (Interviewee 5)

In this particular case, it was primarily internal factors that deter-mined the end of the Port Wine Route, chiefly a lack of funding, debt (overly ambitious reconstruction works for the headquarters) and a new, more expensive management team, as well as a lack of engage-ment of public and private partners (Dimitrovski & Rachão, 2017). Figure 20.1 schematises the leadership constructions used since the crea-tion of the Porto Wine Route until its decline. Another essential internal pillar of a route is collaboration between the members and the Port Wine Route soon showed little ability for this:

Of the big producing companies we only had one and of wineries we had two or three. The private ones with some capacity initially showed no interest. The route and the adherents were micro and small firms with-out critical mass and withwith-out the capacity to welcome or accommodate large groups. Then, at this stage, there is always the hard core (five to six adherents) that participates and accompanies and some collaboration was achieved, but only on the basis of personal relationships. (Interviewee 5)

At this point, despite the remaining physical evidence (in particular signage is still posted all over the region and the website can still be consulted), the Port Wine Route is no longer functioning, being practically extinct.

261 262 263 264 265 266 267 268 269 270 271 272 273 274 275 276 277 278 279 280 281 282 283 284 285 286 287 288 289 290 291 292 293 294

Finally, it is of note that despite the growing interest in wine tour-ism in the Douro region, an increasing number of tourists visiting on an annual basis and a significant presence of Portuguese wine and wine tourism within the global tourism market, the decline—and even-tually the failure—of the Port Wine Route was provoked by mainly internal factors. These negative results, however, are in line with earlier findings affirming that different classes of a product reflect different life cycle curves (Polli & Cook, 1969). In this specific case, while wine tour-ism is booming in the Douro region, the Port Wine Route has ended.

1996 1999/2000–2006/2007 2007/2008 2010/2011

Creation stage Development stage Redefining of leadership Decline stage

Public institutions Private firms Mixed leadership Disaggregation ofleadership

Association of Adherents IVDP Casa do Douro Douro Sul Tourism Board IVDP Association of Adherents Douro Sul Tourism Board 1 Representative of the municipalities IVDP Association of Adherents Douro Sul Tourism Board 1 Representative of the municipalities

Fig. 20.1 The Port Wine Route development process (Source Authors’ own elaboration) 295 296 297 298 299 300 301 302 303

The Vinho Verde route is positioned somewhere between the growth and maturity stage allowing its management to think strategically about its future. The Vinhos Verdes Wine Route was created in 1996 and later, between 2008 and 2009, the sub-route of Vinho Verde Alvarinho was generated.

‘The managing entity of the route is still the city hall of Melgaço, which also created this project, and later included the Monção. So now, the route covers the two municipalities […]’. The interpretive centres of

the Alvarinho wine were divided over the two counties: ‘We have created

here in Melgaço the mother house of the route – the Solar of Alvarinho, because of its central location, and the palace and museum of Alvarinho […] in Monção. The tourists can go there and obtain all the informa-tion they need to travel around the territory and visit several enogastro-nomic points […]’. (Interviewee 8)

More results of the interviews are bundled in Table 20.6. When the interviewees were asked about their contributions to the improvement of the wine routes, two issues were commented on by all respondents: the sense of vocational training for the territorial players and the lack of critical mass. With respect to further improvements, both stakeholders of the Vinhos Verdes Wine Route agreed that wine tourism must be more developed, certainly now, as they have recently gained decent infrastruc-tural conditions as well as international recognition:

‘Of course we cannot focus on tourism until we have a consolidated prod-uct. Only after we have consolidated the product and have spread its name worldwide, will larger groups of tourists want to visit the region. We are an ever more fashionable product worldwide’ (Interviewee 9); ‘I think we should go deeper into the concept of wine tourism […].’ (Interviewee 7)

With the exception of the Alvarinho sub-route, in which partnerships are already a reality in the format of a business network, the members of the Vinhos Verdes Wine Route only collaborate in an informal way, namely through personal relationships.

Last, but not least, it should also be noted that one of the actors con-sidered the importance of wine routes to be overestimated.

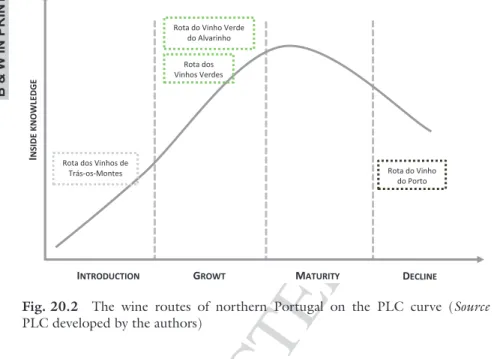

To resume our discussion of the results of our in-depth interviews and the literature review, we have placed the four wine routes of northern Portugal on a graph representing the life cycle of a product (Fig. 20.2).

304 305 306 307 308 309 310 311 312 313 314 315 316 317 318 319 320 321 322 323 324 325 326 327 328 329 330 331 332 333 334 335 336 337 338 339

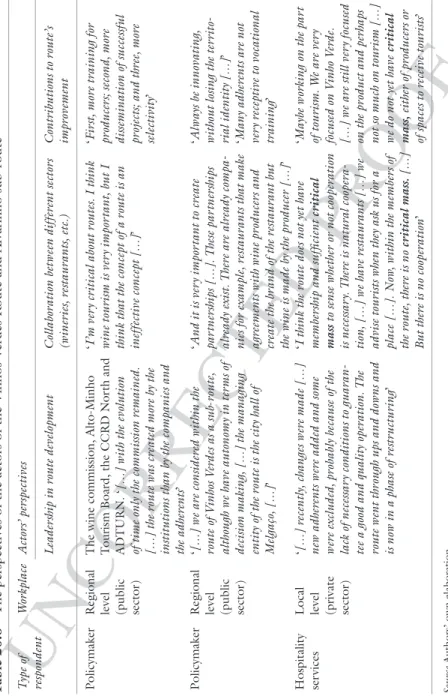

T

able

20.6

The perspectives of the actors of the V

inhos V

er

des Route and Alvarinho sub-r

oute

Sour

ce

Authors’ own elaboration

T

ype of respondent

W

orkplace

Actors’ perspectives Leadership in route development

Collaboration between dif

fer

ent sectors

(wineries, r

estaurants, etc.)

Contributions to route’s improvement

Policymaker

Regional level (public sector)

The wine commission, Alto-Minho Tourism Boar

d, the CCRD Nor

th and

ADTURN. ‘

[…] with the

evolution

of time only the commission r

emained.

[…] the route was cr

eated mor

e by the

institutions than by the companies and the adher

ents

’

‘I’m ver

y critical about routes. I think

wine tourism

is ver

y impor

tant, but I

think that the concept of a route is an inef

fective concept […]

’

‘First, mor

e training for

producers; second, mor

e

dissemination of successful projects; and thr

ee, mor

e

selectivity

’

Policymaker

Regional level (public sector)

‘[…] we ar e consider ed within the route of V inhos V er des as a sub -route,

although we have autonomy in ter

ms of

decision making, […] the managing entity of the route is the city hall of Melgaço, […]

’ ‘And it is ver y impor tant to cr eate par tnerships […]. These par tnerships alr

eady exist. Ther

e ar

e alr

eady compa

-nies for example, r

estaurants that make

agr

eements with wine producers and

cr

eate the brand of the r

estaurant but

the wine is made by the producer […]

’

‘Always be innovating, without losing the ter

rito -rial identity […] ’ ‘Many adher ents ar e not ver y r eceptive to vocational training ’

Hospitality services

Local level (private sector)

‘[…] r

ecently, changes wer

e made […]

new adher

ents wer

e added and some

wer

e excluded, probably because of the

lack of necessar

y conditions to guaran

-tee a good and quality

operation

. The

route went through ups and downs and is now in a phase of r

estr

ucturing

’

‘I think the route does not yet have membership and suf

ficient

critical

mass

to sense whether or not cooperation

is necessar y. Ther e is natural coopera -tion, […] we have r estaurants […] we

advise tourists when they ask us for a place

[…]. Now

, within the members of

the route, ther

e is no critical mass. […] But ther e is no cooperation ’

‘Maybe working on the par

t of tourism . W e ar e ver y focused on V inho V er de. […] we ar e still ver y focused

on the product and per

haps

not so much on tourism […] we do not yet have

critical mass, either of producers or of spaces to r eceive tourists ’

At present, according to our data, the Trás-os-Montes Wine Route is in the ‘embryonic’ phase that precedes the introduction of the prod-uct to the market, the Vinho Verde Wine Route and the Alvarinho Wine Route are clearly in a growth phase, while the Port Wine Route is in the phase of decline.

To close the discussion, we put all the wine routes in Portugal on another chart. Their place on the chart is mainly based on the figure elaborated in the ARVP—Strategic Plan, which presents a development matrix of the wine routes of the Association based on 11 strategic and communication indicators (IDTOUR, 2016, p. 96). We combined this perspective with the data we obtained through our in-depth interviews, our desk research and our growing knowledge of the sector. We also sent our proposal to all those responsible for the wine routes and those who answered all approved the configuration of Fig. 20.3.

What counts is the placement of a wine route in the correct phase. Within each phase, the routes are placed arbitrarily.

The Trás-os-Montes Wine Route, the Pico Island Wine Route, the Madeira Island Wine Route and the Algarve Wine Route are in the

INTRODUCTION GROWT MATURITY DECLINE

I

NSIDE KNOWLEDGE

Rota dos Vinhos de Trás-os-Montes

Rota dos Vinhos Verdes Rota do Vinho Verde

do Alvarinho

Rota do Vinho do Porto

Fig. 20.2 The wine routes of northern Portugal on the PLC curve (Source PLC developed by the authors)

340 341 342 343 344 345 346 347 348 349 350 351 352 353 354 355 356 357 B & W IN PRIN T

introduction stage (thus far, the first two exist only on paper); the Beira Interior Wine Route and the Tejo Wine Route are at the beginning of the growth phase, while the Dão Wine Route, the Cister Vineyard Route, the Bucelas, Carcavelos and Colares Wine Route, the routes of the wines of Lisbon, the Alvarinho Wine Route and the Vinho Verde Wine Route are already more strongly developed; the Bairrada Route, the Setúbal Peninsula Wine Route and the Alentejo Wine Route are comparatively highly ranked in the maturity stage; only the Port Wine Route is in the phase of decline.

concLudIng reMarks

The wine routes of Northern Portugal represent three of the possi-ble PLC stages: together with the Pico Island Wine Route, the Trás-os-Montes Wine Route is at the very beginning of its life cycle. The growth stage in Portugal is the best represented with eight routes, among which are the Vinho Verde Wine Route and Alvarinho Wine Route. While northern Portugal is not represented in the maturity phase, the Port Wine

INTRODUCTION GROWTH MATURITY DECLINE

I

NSIDE KNOWLEDGE Rota dos Vinhos de

Trás-os-Montes Rota do Vinho

da Madeira Rota dos Vinhos

da Ilha do Pico Rota dos Vinhos

do Algarve

Rota dos Vinhos de Lisboa Rota do Vinho do Dão Rota dos Vinhos de Bucelas,

Carcavelos e Colares

Rota da Vinha da Beira Interior

Rota das Vinhas de Cister

Rota dos Vinhos do Tejo Rota dos Vinhos Verdes

Rota do Vinho Verde do Alvarinho Rota do Vinho do Alentejo Rota do Vinho da Bairrada Rota dos Vinhos da Península de Setúbal

Rota do Vinho do Porto

Fig. 20.3 The Portuguese wine routes on the PLC curve (Source PLC devel-oped by the authors)

358 359 360 361 362 363 364 365 366 367 368 369 370 371 372 373 B & W IN PRIN T

Route stands alone in the decline stage. In other words, there is consider-able potential for the growth of the wine routes in northern Portugal.

The findings from the literature suggest that the potential for wine tourism is recognised by the main figures responsible for organising and steering tourism and economic development. However, in the north of Portugal, the wine routes as an important niche tourism product are not following the growth pattern of wine tourism in general. This confirms earlier findings that wine routes are fashionable among owners and officials, but not necessarily among wine tourists (López-Guzmán, Sanchez Canizares, & García, 2010). In other words, implementing a wine route does not at all guarantee that the tourists will find their way to it in large numbers.

Based on the results of our in-depth interviews, our research team supports the advice of Papatheodorou (2004) to pay full attention to the key stakeholders in order to decide the place of ‘their’ tourism product in the PLC.

This chapter depicts the status quo of the wine routes in Portugal. The stakeholders, however, expect more from a research team than mere descrip-tive conclusions. Thus, in the near future our sources will be screened from the perspective of what can be done in each stage to improve the perfor-mance of each wine route. Some benchmarking exercises will also contribute to the formulation of solutions that can be applied in the territory.

Acknowledgements This research is part of the wider project, INNOVINE & WINE—Vineyard and Wine Innovation Platform—Operation NORTE -01-0145-FEDER-000038, co-funded by European and Structural Investment Funds (FEDER) and by Norte 2020 (Programa Operacional Regional do Norte 2014/2020—Funding Reference: POCI-01-0145-FEDER-006971), as well as by national funds through the FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology—under project UID/SOC/04011/2013.

references

Altinay, L., & Paraskevas, A. (2008). Planning research in hospitality and tourism. London: Routledge and Taylor & Francis.

Benur, A. M., & Bramwell, B. (2015). Tourism product development and prod-uct diversification in destinations. Tourism Management, 50, 213–224. Biggadike, E. R. (1981). The contributions of marketing to strategic

manage-ment. Academy of Management Review, 6(4), 621–632.

374 375 376 377 378 379 380 381 382 383 384 385 386 387 388 389 390 391 392 393 394 395 396 397 398 399 400 401 402 403 404 405 406 407 408 409

Brás, J. M., Costa, C., & Buhalis, D. (2010). Network analysis and wine routes: The case of the Bairrada Wine Route. The Service Industries Journal, 30(10), 1621–1641.

Bregoli, I., Hingley, M., Del Chiappa, G., & Sodano, V. (2016). Challenges in Italian wine routes: Managing stakeholder networks. Qualitative Market

Research: An International Journal, 19(2), 204–224.

Brunori, G., & Rossi, A. (2000). Synergy and coherence through collective action: Some insights from wine routes in Tuscany. Sociologia Ruralis, 40(4), 409–423.

Bruwer, J. (2003). South African wine routes: Some perspectives on the wine tourism industry’s structural dimensions and wine tourism product. Tourism

Management, 24(4), 423–435.

Butler, R. W. (1980). The concept of the tourist area life-cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer, 24(1), 5–12.

Correia, L., Ascenção, M. J. P., & Charters, S. (2004). Wine routes in Portugal: A case study of the Bairrada Wine Route. Journal of Wine Research, 15(1), 15–25.

da Conceição Gonçalves, V. F., & Águas, P. M. R. (1997). The concept of life cycle: An application to the tourist product. Journal of Travel Research, 36(2), 12–22.

Day, G. S. (1981). The product life cycle: Analysis and applications issues. The

Journal of Marketing, 45, 60–67.

‘Despacho Normativo n.° 669/94, de 22 de Setembro de 1994’ in Diário da

República n.° 220/1994, Série I-B de 1994-09-22, pp. 5713–5714.

DGT. (1991). Livro Branco do Turismo. Lisboa: Direcçao Geral do Turismo. Dimitrovski, D., & Rachão, S. (2017, June 1–3). ‘Evaluating Port Wine Route

failure antecedents. In The Second International Scientific Conference “Tourism

in Function of the Development of the Republic of Serbia”: The Tourism Product as a Factor of Competitiveness of the Serbian Economy and Experiences of Other Countries (TISC 2017) (pp. 95–112), Vrnjacka Banja, Serbia.

Dodd, T., & Beverland, M. (2001). Winery tourism life-cycle development: A proposed model. Tourism Recreation Research, 26(2), 11–21.

Eurostat. (2017). Area under vines, 2015. Statistics Explained. Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/File:Area_ under_vines,_2015_(%25)-Fig1.png.

Gardner, D. (1987). The product life cycle: Its role in marketing strategy. Die

Unternehmung, 41, 219–231.

Golder, P. N., & Tellis, G. J. (2004). Growing, growing, gone: Cascades, diffu-sion, and turning points in the product life cycle. Marketing Science, 23(2), 207–218. 410 411 412 413 414 415 416 417 418 419 420 421 422 423 424 425 426 427 428 429 430 431 432 433 434 435 436 437 438 439 440 441 442 443 444 445 446 447 448 449 450

Hashimoto, A., & Telfer, D. J. (2003). Positioning an emerging wine route in the Niagara region: Understanding the wine tourism market and its impli-cations for marketing. Journal of Travel and Tourism Marketing, 14(3–4), 61–76.

Hofer, C. W. (1975). Toward a contingency theory of business strategy. Academy

of Management Journal, 18(4), 784–810.

Hofer, C. W., & Schendel, D. (1978). Strategy formulation: Analytical concepts. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Company.

IDTOUR. (2016). ARVP. Plano Estratégico. Cartaxo: Associação das Rotas dos Vinhos de Portugal.

Komppula, R., Hakulinen, S., & Saraniemi, S. (2010). The life cycle of a spe-cific tourist product—Christmas in Lapland. Managing Change in Tourism:

Creating Opportunities-Overcoming Obstacles, 4, 87.

Levitt, T. (1965). Exploit the product life cycle. Harvard Business Review, 43, 81–94.

López-Guzmán, T., Sanchez Canizares, S. M., & García, R. (2010). Wine routes

in Spain: A case study. Turizam: znanstveno-stručni časopis, 57(4), 421–434.

Novais, C. B., & Antunes, J. (2009). O contributo do Enoturismo para o desen-volvimento regional: o caso das Rotas dos Vinhos. In Actas do 15° Congresso

da Associação Portuguesa de Desenvolvimento Regional (pp. 1253–1280).

Cabo Verde: APDR.

Papatheodorou, A. (2004). Exploring the evolution of tourism resorts. Annals of

Tourism Research, 31(1), 219–237.

Patton, A. (1959). Stretch your product’s earning years: Top management’s stake in the product life cycle. Management Review, 48(6), 9–14.

Polli, R., & Cook, V. (1969). Validity of the product life cycle. The Journal of

Business, 42(4), 385–400.

‘Resolução do Conselho de Ministros n.° 17-B/86, 14 de Fevereiro de 1986’ in Diário da República n.° 37/1986, 1° Suplemento, Série I de 1986-02-14, 404-(2)-404-(5).

Rink, D. R., & Swan, J. E. (1979). Product life cycle research: A literature review. Journal of Business Research, 7(3), 219–242.

Russell, R. (2005). Chaos theory and its application to the TALC model. The

Tourism Area Life Cycle, Volume 2: Conceptual and Theoretical Issues, 2,

164–179.

Russell, R., & Faulkner, B. (1999). Movers and shakers: Chaos makers in tour-ism development. Tourtour-ism Management, 20(4), 411–423.

Simões, O. (2008). Enoturismo em Portugal: as rotas de vinho. Pasos. Revista de

turismo y patrimonio cultural, 6(2 es), 269–279.

Smith, S. L. (1994). The tourism product. Annals of Tourism Research, 21(3), 582–595. 451 452 453 454 455 456 457 458 459 460 461 462 463 464 465 466 467 468 469 470 471 472 473 474 475 476 477 478 479 480 481 482 483 484 485 486 487 488 489 490 491 AQ6

THR. (2006). Gastronomia e Vinhos. 10 produtos estratégicos para o

desenvolvi-mento do turismo em Portugal. Lisboa: Turismo de Portugal.

Tooman, L. A. (1997). Applications of the life-cycle model in tourism. Annals of

Tourism Research, 24(1), 214–234.

Turismo de Portugal. (2007). Plano Estratégico Nacional do Turismo para o

Desenvolvimento do Turismo em Portugal. Lisboa: Turismo de Portugal e

MEI.

Turismo de Portugal. (2015). Turismo 2020. Cinco princípios para uma

ambição. Turismo de Portugal. Lisboa: Turismo de Portugal e MEI.

Veal, A. J. (2006). Research methods for leisure and tourism: A practical guide (3rd ed.). Harlow, England: Prentice Hall and Pearson Education.

Zsuzsanna, T. I. (2012). Thematic routes—Wine routes. Eger: Eszterházi Károly Fóiscola. 492 493 494 495 496 497 498 499 500 501 502 503 504

Book ID:

459551_1_En

Chapter No:

20

Please ensure you fill out your response to the queries

raised below and return this form along with your

corrections.

Dear Author,

During the process of typesetting your chapter, the following queries have arisen. Please check your typeset proof carefully against the queries listed below and mark the necessary changes either directly on the proof/online grid or in the ‘Author’s response’ area provided

Query Refs. Details Required Author’s Response

AQ1 Please confirm if the corresponding author is correctly identified. Amend if necessary.

AQ2 Please suggest whether the term ‘northern Portugal’ can be changed to ‘Northern Portugal’ throughout the chapter.

AQ3 Please suggest whether the term ‘nineties’ can be changed to ‘1990s’ in the sentence ‘Although Portugal has always been a …’.

AQ4 Please check that the term ‘a)’ in the row ‘9. Rota da Vinha da Beira Interior’ of Table 20.3 is presented correct or amend if necessary.

AQ5 Please check whether the edit made in the sentence ‘The main characteristic of the PLC is that …’ conveys the intended meaning.

AQ6 Kindly check and confirm the inserted the publisher location is correct for reference ‘IDTOUR (2016)’.

Please correct and return this set

Instruction to printer

Leave unchanged

under matter to remain

through single character, rule or underline

New matter followed by or or or or or or or or or and/or and/or e.g. e.g. under character over character new character new characters through all characters to be deleted

through letter or

through characters under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed under matter to be changed Encircle matter to be changed (As above) (As above) (As above) (As above) (As above) (As above) (As above) (As above) linking characters through character or where required between characters or words affected through character or where required or

indicated in the margin

Delete

Substitute character or

substitute part of one or

more word(s)

Change to italics

Change to capitals

Change to small capitals

Change to bold type

Change to bold italic

Change to lower case

Change italic to upright type

Change bold to non-bold type

Insert ‘superior’ character

Insert ‘inferior’ character

Insert full stop

Insert comma

Insert single quotation marks

Insert double quotation marks

Insert hyphen

Start new paragraph

No new paragraph

Transpose

Close up

Insert or substitute space

between characters or words

Reduce space between

characters or words

Insert in text the matter

Textual mark

Marginal mark

Please use the proof correction marks shown below for all alterations and corrections. If you

in dark ink and are made well within the page margins.

wish to return your proof by fax you should ensure that all amendments are written clearly

View publication stats View publication stats