UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS

MARE NOSTRUM – MILITARY HISTORY AND NAVAL POWER IN ROME (2nd century BCE – 1st Century CE)

DANIELA MARIA DANTAS GOMES

Orientadores: Prof. Doutor Amílcar Manuel Ribeiro Guerra Prof. Doutor José Manuel Henriques Varandas

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor no ramo de História, na especialidade de História Antiga

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE LETRAS

MARE NOSTRUM – MILITARY HISTORY AND NAVAL POWER IN ROME (2nd century BCE – 1st Century CE)

DANIELA MARIA DANTAS GOMES

Orientadores: Prof. Doutor Amílcar Manuel Ribeiro Guerra Prof. Doutor José Manuel Henriques Varandas

Tese especialmente elaborada para obtenção do grau de Doutor no ramo de História, na especialidade de História Antiga

Júri:

Presidente: Doutor Hermenegildo Nuno Goinhas Fernandes, Professor Associado e Director da Área de História da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa;

Vogais:

- Doutor José Luís Lopes Brandão, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Coimbra;

- Doutora Cláudia do Amparo Afonso Teixeira, Professora Auxiliar da Escola de Ciências Sociais da Universidade de Évora;

- Doutor Rui Manuel Lopes de Sousa Morais, Professor Auxiliar com Agregação da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade do Porto;

- Doutor João Pedro Pereira da Costa Bernardes, Professor Associado com Agregação da Faculdade de Ciências Humanas e Sociais da Universidade do Algarve;

- Doutor Nuno Manuel Simões Rodrigues, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa;

- Doutor Amílcar Manuel Ribeiro Guerra, Professor Associado da Faculdade de Letras da Universidade de Lisboa, orientador.

Este projeto de investigação teve o apoio da Universidade de Lisboa e da Faculdade de Letras

«Quidam eximia magnitudinem et forma in proximo sedens repente apparuit harundine canens ad quem audiendum cum praeter pastores plurimi etiam ex stationibus milites concurrissent interque eos et aenatores rapta ab uno tuba prosiliuit ad flumen et ingenti spiritu classicum exorsus pertendit ad alteram ripam tunc Caesar Eatur inquit quo deorum ostenta et inimicorum iniquas uocat iacta alea est inquit».

(Suet. Iul. 32)

6 RESUMO / ABSTRACT

Resumo: A investigação da componente marítima e do poder naval no mundo romano

têm sido por vezes secundarizados, por oposição à influência da questão terrestre. Esta secundarização faz-se sentir com maior incidência em determinados momentos cronológicos. Apesar de existir um número considerável de estudos que se dedicam às marinhas do período imperial, estes diminuem significativamente quando se pretende observar o período republicano, e a análise da construção do espaço de influência romano, ainda que inclua referências à questão da relação de Roma com o mar, não a coloca com frequência como ponto central de observação. Assim, trabalhos que observem Roma com o mar como ponto central de observação, e estudos que se dediquem à construção do poder naval romano, sobretudo quando observado para cronologias mais recuadas, são ainda escassos, e a área da investigação que pretende observar os primeiros momentos de Roma no mar, bem como os períodos de transição subsequentes, exige ainda maior investimento no estudo do passado. Tendo observado essa lacuna, e no seguimento de investigações anteriores que se dedicaram aos primeiros esforços navais de Roma no século III a. C. (nomeadamente, na Primeira Guerra Púnica, que opõe Roma a Cartago), surge este estudo, que pretende observar a transformação e concretização de Roma enquanto poder marítimo ao longo do século I a. C., salientando-o de um ponto de vista concreto, nomeadamente o da História Militar (como sugere o próprio título, «História Militar e Poder Naval em Roma»).

Esta dissertação pretende assim observar o modo como a República Romana cresce e se organiza enquanto potência marítima após as Guerras Púnicas, analisando-a enquanto talassocracia, na sequência da evolução do pensamento naval estratégico enquanto linha condutora das cidades-estado do Mediterrâneo. Para proceder a esta observação, são focados quatro pontos-chave: comando, embarcações, portos e conceitos. O capítulo inicial e o capítulo final, tendo em conta a sua natureza, terão maior foco na análise da fonte histórica, por oposição aos capítulos intermediários, onde a investigação passa, sobretudo, por uma observação de ordem arqueológica e iconográfica. No entanto, o objectivo é, acima de tudo, uma posição integrada: apesar de cada elemento da dissertação ter uma componente que prevalece, derivada das necessidades de investigação para o plano de trabalho proposto, pretende-se uma interligação, sempre que possível, de todos os recursos ao alcance do investigador, confrontando-os e daí retirando observações.

A evolução do poder naval de Roma não será somente observada do ponto de vista do seu investimento no Mediterrâneo, mas também da sua intervenção em espaços marítimos que o extravasam, nomeadamente ao longo da costa Atlântica (sobretudo durante campanhas de Gaio Júlio César), mas também em ambientes fluviais, numa tentativa de estabelecer alguns pontos sobre o modo como Roma tira partido dos rios enquanto meios de circulação. Tal é válido não só por via de embarcações, mas também da construção ou destruição de pontes, meios esses que são protegidos e fortificados. Sendo que o século I a. C. coloca os comandantes romanos em contacto com situações diversificadas, em ambientes que são pouco usuais na História de Roma até então, esta investigação pretende apresentar um contributo no sentido de compreender como Roma reage na presença destas circunstâncias, e como é que esta reação se vai traduzir, em termos práticos, nas opções tomadas pelos seus generais e almirantes, quer em termos de combates navais propriamente ditos, quer em termos de utilização do meio aquático como forma de potenciar a deslocação logística de soldados e mantimentos. Neste seguimento, este estudo observa a questão por dois prismas diferentes: por um lado, os conflitos de Roma com adversários externos, como é o caso das Guerras Mitridáticas, das Guerras Gálicas e das duas travessias que Júlio César faz à Grã-Bretanha; por outro, os conflitos internos dentro de Roma, observando a componente naval ao longo das Guerras Civis que irão ocupar a quase-totalidade do primeiro século a. C.: a rivalidade entre Lúcio Cornélio Sula e Gaio Mário, a guerra entre Júlio César e Pompeio, a influência da questão naval nos ataques às regiões costeiras da Península Itálica durante os anos em que Sexto Pompeio domina a ilha da Sicília, e os conflitos do final da República, entre Marco António e Octaviano, que irão terminar em Áccio. Ao longo de toda esta cronologia surgirão frequentes alusões à questão da pirataria, com particular destaque para a questão de Pompeio, o poder que recebe no âmbito do domínio naval, e a forma como desenvolve o combate às amplamente difundidas comunidades de piratas da Cilícia.

Observar a convivência de Roma com o mar na sua totalidade, ainda que de um ponto de vista maioritariamente militar, resultaria numa análise excessivamente extensa, o que levou à delimitação de períodos cronológicos que, neste caso, são momentos de transição e, por isso, permitem uma observação de diferentes momentos nesta relação. Em termos cronológicos, será observado o desenvolvimento do investimento no domínio naval por parte de Roma desde as reformas no exército feitas por Gaio Mário, no ano de 107 a. C., até ao ano em que morre Octaviano, 14 d. C., situando assim o principal foco temporal

8

da investigação no século I antes da nossa Era. Tal não significa, no entanto, que não sejam incluídos elementos de períodos anteriores ou posteriores sempre que a ocasião assim o justifique, sobretudo em casos onde existe continuidade: no que respeita a tipologias de embarcações, e tendo em conta a atual escassez de vestígios arqueológicos, aliada à sua dificuldade de preservação, serão incluídos elementos exteriores ao século I a. C., sendo que, em muitas ocasiões, navios de séculos posteriores são o mais próximo que existe em termos arqueológicos daqueles que poderiam ter sido utilizados nas décadas finais da República Romana. As embarcações são observadas no Mediterrâneo, no Atlântico e nos espaços fluviais; e se o ponto de vista proposto se foca na questão da História Militar, tal não significa que não surjam embarcações de transporte, visto que muitas vezes irão ser utilizadas em contextos de guerra; existe também uma breve abordagem à questão da comunicação em meio naval. A mesma abordagem cronológica será verificará na questão dos Portos: neste ponto, pretende-se observar a questão em abrangência, desde os primeiros portos Romanos junto ao rio Tibre até à fundação de

coloniae maritimae, bem como a incorporação de portos que, não sendo romanos de

origem, são incorporados na esfera de influência romana; consta também uma abordagem particular à questão dos faróis. Estes dois capítulos, de maior incidência na questão material, incluem a observação de elementos arqueológicos, iconográficos e numismáticos, não desvalorizando a importância da fonte escrita, cujo contributo também é apresentado.

O capítulo final, relativo aos conceitos, é de certo modo uma reflexão que resulta da investigação apresentada nos três capítulos anteriores, juntamente com a interpretação de duas questões-chave: a ideia de Mare Nostrum e a de Talassocracia. Os contextos percorridos no que diz respeito a comandantes, embarcações e portos permitem contribuir para a interpretação da relação de Roma com o mar, quer de um ponto de vista concreto, quer de um ponto de vista mais simbólico e ideológico. Neste ponto da investigação, iniciar-se-á com uma análise sob o conceito de «Nosso Mar» noutras civilizações, sobretudo no mundo grego, e depois no mundo romano, observando como fontes gregas e latinas irão apresentá-lo, nas suas uniões e subdivisões; o mesmo será realizado no que diz respeito à questão das «Talassocracias». Como referido, o tema central desta investigação é a observação de Roma do ponto de vista do poder marítimo e, como tal, procurar compreender se Roma pode ser considerada enquanto Talassocracia.

Uma larga componente deste estudo é a criação de questionário. Tendo em conta que as análises da Marinha Romana do período republicano são ainda pouco abundantes, observando a escassa (mas crescente) disponibilidade de contributos arqueológicos, iconográficos e epigráficos, o avanço da observação desta problemática passa também pela apresentação de perguntas. Pretende-se aqui fornecer um elemento de conectividade entre os vários componentes que nos permitem o estudo do passado, elaborando um estudo concertado, através de um fio condutor, de uma problemática mais vasta, e aliando a diversidade de recursos possível. Este trabalho segue, assim, uma opção metodológica que se foca, acima de tudo, na interdisciplinaridade. Através do questionário à fonte histórica, da análise de fontes da iconografia e da numismática, da interpretação dos dados arqueológicos e, acima de tudo, da ligação, sempre que assim seja possível, entre os dados fornecidos pelas várias áreas, espera-se, ainda mais do que responder às questões colocadas, apresentar um contributo para investigações futuras.

Palavras-Chave: Marinha romana; Talassocracia; Embarcações

Abstract: This dissertation intends to observe how the Roman Republic organises itself

as a maritime power following the Punic Wars, analysing it as a thalassocracy in sequence of the evolution of a strategic naval thought as a conductive line of the Mediterranean city-states. We will observe the evolution of the naval investment from the reformations of Gaius Marius in 107 BCE until the death of Gaius Julius Caesar Octauianus in 14 CE. An observation of the naval command processes is intended, as well as a study of the evolution, construction and typology of vessels and respective functions, analysing the armada and the commercial vessels both in maritime and river contexts. The analysis of the supporting infrastructural network to the navy, namely harbours and shipsheds, will also be included. These problematics will be observed through an interdisciplinary perspective, creating a thorough study of these keywords that allows for the observation of the construction of the Roman influence area from the maritime and river space.

10 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This dissertation is the result of four years of research. In the wider outlook of History, four years are nothing. In the smaller world of my personal life, they were four of the fullest years I’ve lived. When looking back, the world in which I began this work, both my own inner living and the outside occurrences, has changed so much that it no longer feels the same while looking back, but some constants have remained, and gratitude must be bestowed where gratitude is due.

Therefore, in the first place, I begin by thanking the University of Lisbon, as it was through the Grant of the Programa de Bolsas de Doutoramento 2016 that so much of this work was possible, through invaluable financial aid. With them, my gratitude towards the Centre for History of the University of Lisbon, which first took me in 2013, in what now seems a lifetime ago, and has led me through not only academic but personal growth. In this sequence, I must thank a number of academics who have accompanied me, some since the very beginning of my time in the world of research back in 2010. To Professor Nuno Simões Rodrigues, who guided my first steps in the world of Classical History, and to Professor José das Candeias Sales, who was kind enough to endure long conversations with utmost patience about the steps to follow next. Two of my earliest mentors in Ancient History, but also in work ethics and keeping hope for what is the world of Ancient studies.

To Professor Andrew Erskine and Professor Andrew Fitzpatrick, another important note of gratitude, for showing the importance of academic cooperation between people of different countries, for aiding me in quests of my own personal doubts and for their readiness to reply to the many difficult questions which a research of this nature brings to one who was only taking her first steps in the questions of ancient navies and Roman imperialism.

To my mother and father, the people who have endured this work’s most difficult and carried with them a burden that was not their own to carry without complaint. The people in our lives shape who we are and our personality, and there is hardly a doubt that the most influential people in my own path are my parents, for showing me the taste for knowledge, but also the importance of hard work.

To my grandmother, who is ever so cheerful and whose energy seems never-ending, for the effort to understand my path and to remind me of the importance of balance.

To Helena Manuelito Sales, for her kind words that never failed me, her incentive and her concern.

To Mandy Valério Marques. Without her, this work would not have been possible at all, not in its current shape. Mandy taught me the language and gave me the tools, so that I could reach this stage in my life and write and speak in English, to share my knowledge further with the academic world.

To Michael Cadywold and Mark Driscoll, for their almost saintly patience and the many hours they spent helping me translate Dutch bibliography. Without their contribution, it would have been nearly impossible to complete such an important section of this work. To the friends I hope to carry with me into this new stage that is approaching, the truest and most patient friends who have started this journey with me and stayed until the very end, a most grateful word. To Liliana Violante, who easily spent hundreds of hours listening to my never-ending babble on everything and nothing. To Amanda Silva, the most positive person I have ever known, who taught me to always look on the bright side of life. To Chloe Purnell, for all the positive incentive and cheerful optimism, the amazing humour, and the writing practice.

To all the friends, family and acquaintances, to everyone who ever influenced my world and myself in any way, as our present self is a cumulation of all our past, and I could not be more grateful for where it led me.

Last, but definitely not the least, to the two most important people in my academic path. To my supervisor, Amílcar Manuel Ribeiro Guerra, and my co-supervisor, José Manuel Henriques Varandas. They have followed my journey for so long, guided me through my Master’s, and did not hesitate to do the same through this PhD. My gratitude towards them cannot be measured in words, and this is but a small acknowledgement of two academics who are brilliant in their own right, but who are also kind, understanding, patient people and have aided not only myself, but countless other students.

INDEX

Resumo / Abstract – 6 Acknowledgements – 10 Abbreviations – 17 Introduction – 19

Chapter I. War and War chiefs. De Bello Navale

• Commanders at sea: the problematic – 37

Against Foreign Forces

1. The Jugurthine War and the Cimbrian invasion – 41 2. The First Mithridatic War – 50

3. The Second Mithridatic War – 76

4. Lucius Licinius Lucullus and Pompeius: The Third Mithridatic War – 78 5. Pompeius and Piracy – 88

6. The Parthian Wars – 92

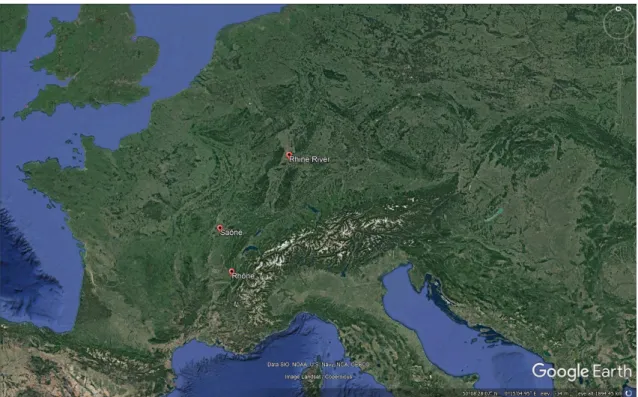

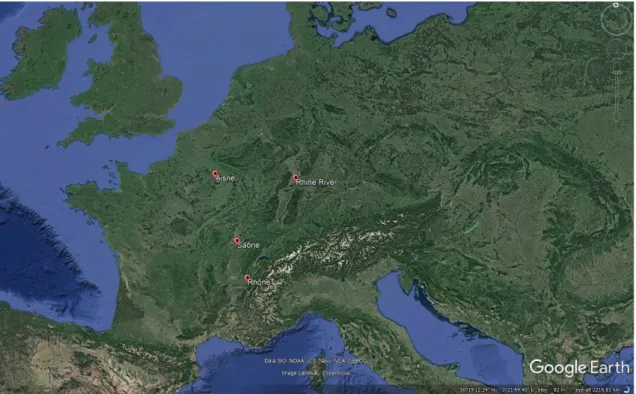

7. The Gallic Wars and the fluvial corridor: the Rhone, the Saône and the Rhine – 92

8. A change of tides: the first incursion in Great Britain – 110 9. Caesar’s solution: the second invasion of Britain – 114

10. The second crossing of the Rhine and the campaign against Vercingetorix: bridges – 117

Internal Conflicts

11. The Social Wars – 128

12. Gnaeus Pompeius vs Julius Caesar – 136

13. The rise and fall of the Second Triumvirate – 148

Chapter II. Ships. Velae et Remi

• Approaching Roman ships in the 21st century – 179

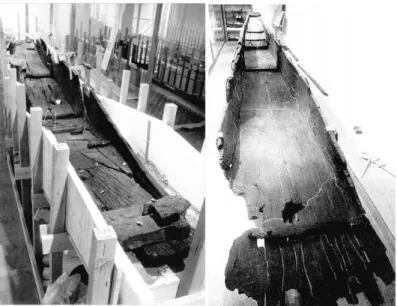

• Archaeological Evidence – 182 Atlantic Tides – 185 1. Belgium – 189 o Brugges wreck – 190 o Pommeroeul – 191 2. France – 193 o Chalon-sur-Saône – 194

o Galere de César and Jules Verne – 195 o Arles-Rhône – 198

o Lyon (Tolozan and Parc Saint-Georges) – 200 3. Great Britain – 201

14

o Barland’s Farm boat – 205

o New Guy’s House – 207

o County Hall – 207 o Guernsey – 209 4. Netherlands – 211 o De Meern ships – 211 o Druten 1 – 217 o Kapel Avezaath – 219 o Vechten – 221 o Zwammerdam shipwrecks – 222 5. Germany – 227

o Mainz and Oberstimm – 227 6. Switzerland – 229

o Bevaix – 229 o Yverdon – 230 7. Slovenia – 231

o Sina Gorica and Lipe – 231 8. Portugal: A particular case-study – 232

Mediterranean Challenges – 234 1. Croatia – 234 2. Italy – 235 o Aquileia – 235 o Stella 1 – 236 o Alberoni – 236 o Comacchio – 237

o Grado (Iulia Felix) and the Fiumicino Findings – 238 o Herculaneum and Monfalcone – 242

3. Sardinia – 244 o Spargi Wreck – 244 4. Greece – 245 o Antikythera – 245 5. Spain – 245 • Warships – 246 • Materials – 252 1. Timber – 252 2. Metal – 255

• Other resources for ancient ship analysis – 266 1. Historical sources – 269

2. Engines – 274

3. The Trireme and Quinquereme – 280 4. The hemiolia and the myoparos – 288 5. Ships of the Civil Wars – 293

6. Last Civil War – The Ships of Actium – 298

7. The northern Atlantic ships as stated by the sources – 306 8. The British campaigns – 309

9. Other terminology – 313 10. The sacred ship – 316

11. Ships in the Poetry of Lucan – 316 12. Some notes on iconography – 318

13. Final reflexions on historical sources – fleets and ship ownership – 328 14. Some remarks on communication – 336

Chapter III. Harbours. Limes terrae ac maris

1. Studying ancient harbours: archaeological and epistemological difficulties – 350 2. The harbours of Rome – 359

3. Hydraulic Concrete – 370 4. Continuous growth – 375 5. Harbours in Roman life – 378 6. Harbours of the Civil Wars – 382

7. Other harbours in the Italian Peninsula: Strabo’s accounts – 399

8. Three notable cases: Alexandria, the Piraeus, and the Sicilian shores – 405 9. Caesar’s expeditions – 416

10. Ship sheds and Shipyards – 418 11. Lighthouses – 433

12. Some remarks on iconography – 445

Chapter IV. Mare Alterum, Mare Nostrum

1. Mediterranean Rome and Roman Mediterranean – 479 2. A note about Rhodes – 492

3. A concept of Mare Nostrum – 495 4. Before Rome – Greek inheritances – 499 5. Rome – 505

6. What is, therefore, the «Mare Nostrum»? – 514 7. Was Rome a thalassocracy? – 518

8. A brief note on Naval Triumphs – 522 9. The ever-absent word – 526

Final Considerations – 531 References – 546

ABBREVIATIONS

App. B Civ. – Appian, Bella Civilia App. Mith. – Appian, Μιθριδάτειος

Arist. Hist. an. – Aristotle, Historia animalium. BAlex. – Bellum Alexandrinum

BHisp. – Bellum hispaniense

Caes. BAfr. – Caesar, Bellum Africum Caes. BCiv. – Caesar, Bellum Civile Caes. BGall. – Caesar, Bellum Gallicum Cic. Att. – Cicero, Epistulae ad Atticum

Cic. Leg. Man. – Cicero, Pro lege Manilia or De imperio Cn. Pompeii Cic. Fam. – Cicero, Epistulae ad familiares

Dio Cass. – Dio Cassius Diod. Sic. – Diodorus Siculus

Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom – Dionysius Halicarnassensis, Antiquitates Romanae Div. Aug. – Res Gestae Divi Augustus

Eur. Hel. – Euripides, Helena Eutr. – Eutropius

Flor. – L. Annaeus Florus Gran. Lic. – Granius Licinianus Hdt. – Herodotus

Just. Epit. – Justinus, Epitome (of Trogus) Liv. - Livy

Livy, Per. – Livy, Periochae Luc. – Lucan

Oros. – Orosius Paus. – Pausanias

Plin. HN. – Pliny (the Elder), Naturalis historia Plut. Vit. Ant. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Antonius Plut. Vit. Brut. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Bruttus Plut. Vit. Crass. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Crassus Plut. Vit. Luc. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Lucullus Plut. Vit. Mar. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Marius

18

Plut. Vit. Pomp. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Pompeius Plut. Vit. Sert. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Sertorius Plut. Vit. Sull. – Plutarch, Vitae Parallelae, Sulla Polyaenus, Strat. – Polyaenus, Strategemata Polyb. – Polybius

Ps. Xen. Const. Ath. – Pseudo-Xenophon, Constitution of the Athenians Sall. Iug. – Sallust, Bellum Iugurthinum

Sen. Ep. – Seneca the Younger, Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium Strab. – Strabo

Suet. Aug. – Suetonius, Divus Augustus Suet. Iul. – Suetonius, Divus Iulius Tac. Ann. – Tacitus, Annales Tac. Hist. – Tacitus, Historiae Veg. Mil. – Vegetius, De re militari Verg. Aen. – Vergilius, Aeneid.

Vitr. De Arch. – Vitruvius, De architectura Xen. Hell. – Xenophon, Hellenica

INTRODUCTION

«L’histoire néglige presque toutes ces particularités, et ne peut faire autrement ; l’infini l’envahirait. Pourtant ces détails, qu’on appelle à tort petits – il n’y a ni petits faits dans l’humanité, ni petites feuilles dans la végétation – sont utiles. C’est de la physionomie des années que se compose la figure des siècles.»

«Nul n’est bon historien de la vie patente, visible éclatante et publique des peuples s’il n’est en même temps, dans une certaine mesure, historien de leur vie profonde et cachée ; et nul n’est bon historien du dedans s’il ne sait être, toutes les fois que besoin est, historien du dehors. L’histoire des mœurs et des idées pénètre l’histoire des événements, et réciproquement. Ce sont deux ordres de faits différents qui se répondent, qui s’enchaînent toujours et s’engendrent souvent. (…) La vraie histoire étant mêlée à tout, le véritable historiant se mêle de tout.»

Victor Hugo, Les Misérables

The discussion of what History means, of what Historical truth means, and of what makes a good Historian, is one which has lasted centuries and will probably last many centuries more. It is a question which is often in accordance with the currents of thought that dominate a certain time, the philosophies of each individual. There were periods in time where the great events were those to which History paid the most attention; there were others in which there was a growth of general History, compared History, the

longue durée. Our work is not meant to discuss the Theory of History. In each theorical

approach to how one should face reading and writing on ancient chronologies, there will be points with which we agree and disagree; each author has a legacy from which historians incorporate what adjusts most to their current investigation. We chose to open with these two quotes by Victor Hugo, regardless of other positions on historiography, as it fits our own, as we will explain.

«Mare Nostrum: Military History and Naval Power in Rome» is the chosen title of this work. It is complemented by a set chronological barrier: 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE. Victor Hugo stated that to understand History, the historian must have a dual approach, complementary and interdisciplinary: to understand the past, as much as this understanding is possible, one must look at several fields. It is not possible to understand

20

public life without understanding the interior life of peoples; to understand the inner sphere of peoples, one must understand the exterior. To understand what is visible, we must try and understand subjects that are invisible; to understand the invisible, we must look at physical evidence. This is the approach we attempt to follow, one which combines visible and invisible, the more immediate aspects of what one can see and touch with the less obvious points that can be interpreted from the memory of peoples through the legacy of ancient sources. To reach the past one must look into all testimonies, archaeological, iconographic, epigraphic and written sources, which give different contributes, different insight, and allow researchers to adapt their studies and compare the information given by each or complement it when it is amiss. Historical sources cannot show us how an ancient ship truly was, as they lack the visual cue; archaeological sources cannot show us how ancient commanders worked in the several situations of naval life.

The conductive line of our study, visible in the title, is the construction of the Mare

Nostrum. To observe something as vast and as impactful as this notion, which has

crossed the centuries, there are many different approaches available. In this case, the approach will be made through «military history and naval power», two of many possible key-points to allow the understanding of a wider problematic. To understand the Mare Nostrum, we will look at «military history and naval power», whereas to observe «military history and naval power», we will go through the idea of Mare

Nostrum. In the course of this dissertation, this point may be more or less obvious

depending on the many underlying problematics within each topic, but it is the ever-present line which will guide the flow of the work. As with all other works, however, which are limited by time and resources, there will be epistemological decisions that one has to make, as it is not possible to study all within a subject in a single attempt. Therefore, this introduction suits the purpose of explaining the general directions of the study and fit them within the theme and the chronologic approach.

Beginning with the latter, it is important to explain and justify the choice of the specific timeframe we present. If one wishes to study military history and naval power in Rome, there are many periods in which it can be observed. First and foremost, this period was chosen because the intention was to study the construction of the Mare Nostrum, rather than reach the chronology in which it is already made. It is not our purpose to observe imperial navies. These have been object of several studies, whether particular works

about the fleets themselves or included in the wider context of the army, and one could mention, for instance, the work of Le Bohec, L’Armée Romaine, sous le Haut-Empire (1989), which includes a section on the imperial navy; the several chapters included by Pitassi in The Navies of Rome (2010), which has a vast timespan but does not disregard the imperial period, and The Roman Navy: Ships, Men & Warfare 350 BC – AD 475; Oorthuijs’ chapter «Marines and Mariners in the Roman Imperial Fleets», seen in The

Impact of the Roman Army (200 BC – AD 476), published in 2007; and the two recent

compilations by Raffaele d’Amato, Imperial Roman Naval Forces 31 BC – AD 500 (2009) and Imperial Roman Warships 27 BC – 193 AD (2016). There is extensive bibliography on the Imperial Navy, the classis which crossed the Mediterranean and even the Atlantic after the collapse of the Republic.

The same cannot be said for the moment in which Rome’s naval power is being constructed, however. One of the greatest issues of our work was precisely finding updated bibliography, which seems to contrast with the extension of the bibliographical references which we present at the end of the dissertation. The issue is that although we have found a vast number of undoubtedly helpful publications, there is a very limited amount which actually dedicates itself exclusively to the matters that we intend to observe. The exception, which was an essential element of this work, were the many studies regarding very specific ships and harbours, studies that reached us separately and that have the purpose to observe each individual situation in a detailed manner, and that we attempted to assemble together, at least in their major portions, in a way so as to provide an ample overview. However, we had to consider that most of them treat subjects of chronologies which, although close to our proposed frame, are often not exactly the one in cause.

Encircling our study between the 2nd century BCE and the 1st century CE encloses the first century before our era. Our timeline has a defined starting point and a finish line. We depart from the expeditions of Gaius Marius in Numidia, in the very end of the 2nd century BCE, considering the significant changes which occur within the structure of the Roman army, and finish in 14 CE, the year of death of Octauianus, although the main events that will define our proposed subject end long before 14 CE: we have source material for the first and even second-third centuries of our time, but the main event which concludes our progress is the Battle of Actium. This statement is not one to say that the Battle of Actium is the significant turning-point in the struggle for the

22

Mediterranean, nor that it defined the Mediterranean in itself. The idea of a defining battle, or rather, of a battle as definer of paradigm, often disregards the importance of the entirety of the processes of war which led into the ultimate culmination and outcome of a conflict. More than a defining point, Actium is the culmination of many defining points that came before. We propose to present the 1st century BCE, especially the period between the beginning of the First Mithridatic War and the Last Civil War, as the defining moment in the construction of Rome’s sea power.

If the first century BCE is the focal point, one will observe, throughout this work, that there are significant segments of material belonging to periods which came before and after. Whereas the chapter dedicated to maritime conflicts has a strict time delimitation, this will not be as severe regarding ships and harbours. This option was motivated by several reasons. In what regards ships, there was a natural conditioning regarding the lack of archaeological material which can be specifically ascertained to the 1st century

BCE. There is a portion of the introduced craft which belongs to subsequent periods and, to a lesser extent, to prior time frames. However, until new archaeological records are found, these vessels are the closest that investigation can be of 1st century BCE craft,

both warships and transports. The possibility of some degree of continuity may be evaluated, to an extent, through historical sources, and the proposals of modern bibliography. A similar situation occurs in harbours: we observe several cases of river and sea ports which existed long before the 1st century BCE, but that had an active role during this century; on the contrary, some posterior cases are shown, in a correlation to how the changes of our proposed time-period influenced Rome’s presence at sea. Thus, the proposed period of study ends up being central to transmit the idea of a moment of change, one which contrasts with Rome’s past and influences its future.

Our observation of Roman sea power will follow an approach that greatly extends the Mediterranean. There are many possible theories regarding Rome’s beginnings at sea, from the institution of the duumuiri nauales in 331 BCE to the First Punic War1, but the observation of Rome in the Mediterranean, in its most immediate effects, begins in 264 BCE, when Rome crosses to Sicily to fight against Carthage. There is a long course between the 3rd century BCE and the 1st, many of which involve problematics at sea.

1 See Ladewig’s chapters on the subject. Our work, to a great extent, follows Ladewig’s lines of investigation, which diverge from the previous counterparts, as will be explained throughout the course of the dissertation.

We will observe several conflicts with Illyria2, Macedonia, Sparta; Rome faces the ancient Greek city-states all throughout the 2nd century BCE, establishing its presence in the Eastern banks of the Mediterranean. Later in the century, as it enters a period of transition, it suffers the Cimbrian and Jugurthine conflicts. Its last great maritime rival, however, is Mithridates of Pontus, and that is where our study will start, the beginning of the end of opposition to Rome’s presence in the Mediterranean, and the transition from external to internal conflicts. Our intention is not to affirm that Rome was absent from the Mediterranean before the 1st century BCE, quite the contrary, but to expose this period as a defining moment in the shaping of the Roman mare nostrum and to present the sui generis characteristics of Rome and its connection to the sea, and to show its uniqueness in the general overview of ancient thalassocracies.

To reach this objective, we will divide our work in four sections. The first of them is entirely dedicated to Naval Command, beginning in Gaius Marius and ending in the last Civil Wars of the Roman Republic, namely in 31 BCE, with the Battle of Actium. Our subdivision for this chapter is chronological and, being chronological, it will follow the general flow of wars, to engage in the treatment of «military history» from a naval point of view. There will be a few key-figures of commanders whose names will appear more frequently, less due to a wish to underline their importance but more in sequence of the availability of information through historical sources. More importantly, we will observe the significance of the roles of people who would be second-in-command, especially the function of the consular legates. Our option will be to open this chapter with a case-study, showing the evolution of observation on Roman commanders based on fundamental bibliography, amongst which Lionel Casson’s works, such as his

Illustrated History of Ships & Boats from 1964, Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World in 1971 and The Ancient Mariners – Seafarers and Sea Fighters of the Ancient Mediterranean in 1991, and J. S. Morrison’s Greek and Roman Oared Warships, 399-30 BC (originally published in 1996). We will attempt to answer questions related to

terminology, but, first and foremost, to proceed towards an effective observation of the actions of Roman commanders at war: how was authority distributed within the Roman fleet, what was the connection between commanders on land and sea, how did the commanders organise the logistics of the army and navy at war, and what was the

2 See, for instance, Waterfield’s work on the Roman conquest of Greece, its causes, dimensions and potential intentions.

24

influence of naval resources at war. The latter section will be preponderant, and our attention will be focused on specific combat behaviour rather than nomenclature, for which textual evidence is often scarce and not very clear regarding the Republican fleet. The chapter regarding War and War Chiefs will be divided in two sections: «against foreign forces» and «internal conflicts». These represent the two defining moments of Rome’s relation with sea power in the century and also the transition it seems to undergo. We begin by observing the wars that Rome wages against external threats. As there is scarce archaeological evidence to show how a fleet behaved in a situation of war, whether in dislocation or battle, we will have to rely greatly upon historical sources and bibliography, which we intend to observe in a way as to create questionnaire and new interpretation. There will be three key-points in relation to the confrontation with foreign forces. As mentioned above, the most significant transitional wars in this last stage of the assertion of Roman maritime control are the Mithridatic Wars, which will be observed in great detail, after a shorter approach to Gaius Marius’ role at sea and in rivers. The second key-point is the study of Pompeius’ campaigns against piracy, which in itself begins to show a different type of Roman intervention at sea; this will be followed by shorter insights on the Parthian Wars and, more importantly, the Gallic Wars, in which we will observe the importance of rivers and the fluvial corridors within the European continent.

One final note on this chapter, which may be extended to all the others, is the Roman specificity when compared to other maritime powers. Although we are observing conflicts in which Rome is a direct adversary, one must acknowledge that textual evidence shows that there is a frequent reliance on allies. Whenever it is deemed pertinent, ally participation and intervention on Rome’s maritime affairs will be included for major conflicts, considering their particular relation to Rome and their importance in the construction of Rome’s Mediterranean influence. It is relevant to note that the purpose of this dissertation is not to observe each allied fleet in their specificity, a topic that shall be left for other studies of these problematics. Rather, our position is to include them in our analysis whenever the context seems to justify it, within Rome’s particular approach to war at sea.

The last important moment is the Atlantic campaigns, which we observe in detail due to their nature. Rome is perhaps the first Mediterranean civilisation to have significant intervention on Atlantic coastlines, and Julius Caesar is the figure which allows us to

observe that intervention to greater lengths. First throughout his campaigns in the Iberian Peninsula and then his crossings into Great Britain, we will observe how the Roman systems of command adapt to these different realities, the degrees of success (or lack thereof), and how commanders used to Mediterranean styles of naval battle will adapt to potential enemies across the Atlantic. This justifies the choice of «a change of tides» for the title of this particular moment in our chapter, given the entirely different nature of the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. As we follow a chronological approach throughout the wars, the last external conflict we mention is the Second Crossing of the Rhine, which brings us back to rivers and to the role of fluvial courses.

Our chronological division ends in the separation between external and internal wars. When we return to the matters of internal conflicts in the middle of the first chapter, we return to the beginning of the first century BCE. This is an option taken to facilitate reading and comprehension, and very easily could have been chosen to do otherwise; however, at this point and considering that investigation on the Republican navy is still in its early stages, it felt natural to separate the two spheres, as there seems to be a transition between an external focus to one which is mostly internal. We begin by observing the Social Wars, a moment connected to Rome’s allies, which we will relate, to an extent, with external conflicts; however, as we advance in Roman History, the internal component of wars becomes clearer, as Rome’s conflicts begin to occur within itself. The process involves a study of the Civil Wars, from Gnaeus Pompeius against Julius Caesar to the Second Triumvirate, culminating in the final civil war of the Roman Republic, between Marcus Antonius and Octauianus. Instead of observing them in the more traditional perspective of military power shift on land, we will attempt to look at the civil wars from their influence at sea, or the influence of the sea within the civil wars, raising questions regarding the matter of logistics, supply flow and control of important points across the Mediterranean basin. As much as there is information regarding the Civil Wars themselves, there is scarce information on their maritime component, and through the observation of the movements of the armies we will underline the Mediterranean’s role in the last developments which lead into the ultimate collapse of the traditional structure of the Republic towards a new system of authority, including, amidst other matters, the question of the privatisation or centralisation of military power and how it extended to maritime intervention.

26

Our second chapter will focus exclusively on the problematic of ships. This begins, yet again, with a case study, which develops on the question of studying ancient ships in the 21st century, the resources which are within our reach and those which are not, the material we lack and the one we do have. This will be a chapter which naturally and heavily relies on material evidence, from archaeology to iconography and, whenever possible, epigraphy, especially inscriptions which have been considered of great importance by former bibliography. The strongest ground, although not at all the only, will be the one furnished by the Navis I database, created by archaeologists who dedicate themselves to the analysis of ancient shipwrecks. Our approach, rather than focusing on the generality of shipwrecks, will limit itself to those in which there are actual ship components, rather than observing cargo. As our intention is to provide insight on military history and naval power, this was a conscious option taken to follow the work’s guidelines.

As chapter I was divided in two points to facilitate the building of the work’s general flow, chapter II will follow the same method, plunging amidst «Atlantic Tides» and «Mediterranean Challenges». As war is a global phenomenon, despite this work’s focus being military aspects, all types of ship will be included, from dugout fishing craft to larger-scale naval vessels, as the Roman army would likely have contacted with and taken advantage of the possibilities provided by these vessels. Our option for the bibliography in this chapter was in part conditioned by availability, in the other connected with our methodology. There are scarce recent works on shipwrecks, especially as many of the main sunken ships which have been found thus far are discoveries of the mid of the 20th century, many of which are now beginning to be re-observed through modern technologies, others which are undergoing works of preservation, and some which are neither preserved nor being re-observed. Therefore, much of the bibliography that does exist was written as these ships were found, three or four decades ago, often more. This does not mean it should not be regarded nor included, not only because it is the only bibliography that does exist, but also because it is often the work of archaeologists who were present upon the discovery and have first-hand insight on the craft. The main matters on which we will focus will be construction techniques, dimensions and materials; whenever possible, the method of propulsion and potential speed. Within the chapter dedicated to ships, we will present drawings, 3D

reconstructions and the well-known case of experimental archaeology, the Olympias, for vessels whose finding sites span from the North of Europe to Italy.

As a fleet was not only sustained by warships, and as the Roman army pays special attention to the matter of logistics, we will attribute equal importance to cargo vessels and warships. The latter, of which there are significantly fewer archaeological remains, will be studied nonetheless, and at this point the dual approach of our work will be of particular importance, as we will rely more heavily on historical sources to understand the nature of war craft. We follow an approach in which the events treated in Chapters I and II may coincide, but the way they are treated is different and the information extracted varies in accordance to the needs of each portion of our work. Equally important is the matter of iconography, and we have included the analysis of a number of mosaics and frescoes which contribute for a better understanding of ancient warships. There will be a section which dedicates itself specifically to materials, of which we underline two as the core elements of an ancient ship: timber and metal. Whereas the timber section will analyse the types of trees used in the construction of these ships, their characteristics, resilience and endurance, the metal section will have a significant portion dedicated to the matter of rams, for which we have archaeological and historical evidence, as well as some inclusion of numismatics. Materials that easily deteriorate, such as sails and rope, will also be observed but to a lesser extent, given the current difficulty to interpret them in consequence of the lack of archaeological sources, as well as potential use of war engines on board of ancient warships, such as the sambucas and «towers». The chapter ends with remarks on communication aboard a fleet, a subject which is still scarcely worked, and which is of utmost importance for the functioning of an ancient fleet.

Chapter III is dedicated to harbours. Unlike what is visible for the questions of command and ships, we will not invest, to a great extent, upon the potential ports and anchorages throughout the Atlantic, rather making smaller mentions, for two reasons: firstly, the fact that in spite of the Atlantic Campaigns the Mediterranean is still the physical centre of the Roman empire, and secondly, the lesser investment of the Roman Republic upon Atlantic harbours during this period; whereas there is plenty to be said on Atlantic campaigns throughout the last years of the Republic, there seems to have been more significant architectural presence throughout the European rivers than the Atlantic harbours up to the late decades of the 1st BCE, although this is a subject which can be

28

open to further investigation in the future. Again, we open with a case-study, presenting what we call «archaeological and epistemological difficulties» that one may encounter when looking into ancient harbours. If this is the subject which has more visible physical evidence, it is also one of those that presents a larger number of doubts. They are numerous, but there is little left of ship sheds, shipyards and overall structures which may have been used to protect the ancient ships.

In this chapter, there will be a few core subjects. Firstly, the harbours of Rome, and the question of what a Roman harbour is when contrasted with one that has been incorporated into Rome’s political influence. We will observe the fluvial ports which are born alongside the city and from that space we will develop towards the exterior, into Rome’s connection with Ostia, Brundisium and Dyrrachium, the earliest connections towards the sea. Ostia, in particular, as one of the first Roman maritime foundations, will be observed with particular care, not only from an archaeological point of view but also through its presence across Roman history. This historical relation between harbours across the Mediterranean and Rome will ultimately result in a problematic which attaches itself to what was developed throughout chapter I, which is the distinction between Public and Private, the privatisation of authority and the meaning that a Roman harbour may have had in these two sides of Roman life and politics. This will bring us to one of the last subchapters on this matter, which is titled «harbours of the civil wars», an attempt at understanding the way these locations fit themselves within the internal power-struggle of the city of Rome.

The study of harbours is, perhaps, out of all four chapters of this dissertation, the one in which this dichotomy that we attempt to create between material and written sources is achieved in a fullest form. On the one hand, there is the observation of harbour construction, harbour structures and materials, of which we underline the pozzolana, as one of the most significant in the history of Mediterranean harbour architecture. On the other, the role of harbours in the growth of the Roman maritime empire and its construction as a thalassocracy. It is as if harbours are the last and most durable physical manifestation of Roman maritime expression, and this will be observed throughout the inclusion of long-standing locations which begin as fundamental points for other civilisations, such as the Piraeus and Alexandria, and the way in which Rome incorporates them – or not – as it reconfigures the Mediterranean; moreover, in the way

that Rome extends its own architecture, its own materials, to the new harbours which are built across the sea, as is the case of Caesarea.

The case of the Piraeus, for instance, is notorious: under the specific conditions that accompany Rome’s conquest of the Mediterranean basin, it will not destroy, for instance, Alexandria, which endures the centuries and will last after the final Civil Wars; but the Piraeus is, allegedly, entirely destroyed, a factor which may have archaeological sustentation. This destruction and the factors that surround it are something which ought to be questioned, and there is still much doubt regarding the process itself. Important as well is the question of Sicily: as the first province of Rome and the first stage of Rome’s maritime conquest, its role in the civil wars between Sextus Pompeius and the Second Triumvirate cannot be disregarded, and neither can that of its ports. Once again, we will attempt to gather old and new bibliography alike, especially specialised studies in particular harbours, to create a general overview which seems to be lacking, at this point, in current investigation. As we mentioned above, the portion of this chapter dedicated to the Atlantic will not be as significant as the ones found in Chapters I and II, for the reasons justified above; however, we will include a section regarding the importance of coastal anchorages during Caesar’s Atlantic campaigns, as they have their own relevance in this context.

Returning to the matter of ship sheds and shipyards, we will once again provide information on the most elusive matter of ancient harbours, not only regarding sea-born sites but also observing some inland locations by the river banks and, what is more, the connection which may exist between river harbours, potential shipyards and sea ports, one which intersects with Chapter II in its presentation of vessels that most likely travelled both in coastal and river areas, between land and sea. There is an evident link between all chapters, but those which are most closely bound are II and III, especially as we mentioned our focus on the construction methods of ships in Chapter II, which will be accompanied with questions on the how and with which resources they would have been built in Chapter III. Alongside the infrastructures to support ships and navigation, we shall also include a brief approach to lighthouses. These are simultaneously the matter for which there is more material available, both regarding iconographic, numismatic and archaeological sources, and for which the material itself raises more doubts. Through the observation of several images, provided to us by ancient coins, mosaics and frescos, the interpretation of canon bibliography and the

30

comparison between these resources, we will try for a fresh observation on the matter of ancient lighthouses which may contribute to further interpretations.

The Geographic component, which is also an evident aspect of harbours, is the most immediate, the one which can be observed first and foremost, and in this regard, we will guide ourselves by the reflexions of ancient geographers, of which we underline Strabo. This is a fundamental part of work when attempting to understand the locations without an immediate physical evidence, ports and anchorages that have not left long-lasting signs to our days, but which may have been important for the life of ancient communities. Although we have restricted ourselves regarding the treatment of life in ancient harbours, we will attempt an approach, however brief, to some factors which can be observable through historical and archaeological sources in terms of, for instance, demography, the connection between the people and the sea, and the influence a harbour may have had in daily life. These points are particularly noticeable through a medium which we purposefully left to be observed with greater extension in this chapter, which is that of numismatics. Coins, as immediate elements of the world, elements of trade which would travel from hand to hand, present several decorative components dedicated to nautical elements, ships and harbours; but the latter are of particular significance in this regard, and they seem to provide more relevant information than they would for ships, considering their size.

Although we present imagery throughout the entirety of the chapter, the subject will be taken up again in specificity in the last portion of our analysis, as there is such a vast number of elements that can be included that it naturally develops into its own subchapter. Our main focus will be mosaics, frescoes and coins, which comes as no novelty considering what we have stated above, and that we will attempt to interpret to answer questions on harbour shape, design, function and ship construction. In this regard, Lionel Casson’s work will be fundamental for our approach, as will the many representations which can be found in Trajan’s Column, whose naval imagery has not been largely studied thus far and deserves further interpretation. We will attempt to look at the pictures analysing matters of shape, colour and disposition. Our analysis will not be made from an artistic point of view, as this is not the purpose of this work, but it will be kept in mind that the canons of ancient art would often induce us in misinterpretations of dimension due to the matters of perspective.

Our last chapter, which we call «Mare Alterum, Mare Nostrum», is, to an extent, a reflexion upon the practical implications of the physical and historical evidence presented throughout the remainder three. Throughout the four chapters, we have opted for including an initial imagery which can be considered representative of the general message of the study. The one chosen for chapter IV is a 19th century painting called «The Course of the Empire: The Consummation». In this work, made in 1836, Thomas Cole has depicted the ultimate form of an empire, the point in which it achieves its final potential; the fact that this «consummation» is represented through the inclusion of a harbour, that one can see ships sailing across, is symbolic as a representation of how much the connection with water is a fundamental factor for the fulfilment of an Empire, something which is also found in ancient sources. The entirety of this chapter will be an introduction to approach a question, which is whether we have a Roman Thalassocracy, a Roman «Mare Nostrum», a «Mediterranean Rome and Roman Mediterranean». To look further into the matter, we begin by analysing the matter of Rome’s dependency on the socii nauales, especially of Rhodes, in a more practical approach related to strategy and politics; afterwards, we move towards the mental sphere of the Ancient Mediterranean.

Firstly, through a brief recap of the evolution of ancient Thalassocracies, we will situate Rome’s arrival to the power struggle for the Mediterranean, observing its role in the mind of ancient writers. Afterwards, we will observe the evolution of concepts. The first analysis is of Mare Nostrum, starting with the Greek world, observing its growth into political thought, its pertinence in the Roman world and its presence or absence in the way Rome looks at itself and constructs its own power, both as heir of former traditions and creator of its own sphere. What is the Mare Nostrum for Rome? How did Rome understand the notion? This is a subject on which there is scarce bibliography, as historiography has focused in understanding Rome’s growth as an empire by looking at it from its evolution on land rather than at sea; the sea control is almost set as the ultimate conclusion of land control. We will attempt to provide a new insight by looking at the problematic from a different view.

This leads to the final question that is presented. «Was Rome a thalassocracy?» This is a question left unanswered in the work, and replied to in our final reflexions, to create a division between what has actual historical evidence and what is, at the point, one hypothesis postulated by our investigation but that cannot, as of yet, be confirmed. From

32

the matters of linguistics towards questions such as the Naval Triumphs, their existence and inexistence, we will close the investigation with what we call «the ever-absent word».

There are three notes which are important regarding this dissertation that do not include the general form of the work itself, before entering the final leading points of introduction. One regards the method in which we present conclusions. In the end of Chapters I, II and IV, we have opted for including bullet-point conclusions. Given the extension of this work, it seemed pertinent to include these important points for the understanding of the problematics throughout the work, so that upon reaching the conclusion we can focus on matters such as issues found along the writing and raising potential hypotheses for future investigation, as well as additional reflexions on the general overlook of the work which would not naturally fit within the flow of the dissertation, but are essential as a way to conclude. The absence of this type of bullet-points in chapter III is due to the fact of it being one mostly dedicated to material evidence, which leaves scarce room for re-interpretation; we present and analyse data, but to re-analyse would be to go against our own previous affirmations.

The second regards the matter of names. There is great discussion amidst the academic community on how ancient names should be presented and how ancient writing should be presented. Our options are taken due to matters of practicality. As it is not our goal to discuss this particular problematic, we will approach names and quotes in a way to facilitate the understanding of this specific study. Most of Latin names will keep its original form, with the exception of Julius rather than the classical Iulius, as the name Julius Caesar is deeply ingrained in the current mindset and it is as Julius Caesar that this commander is presented. Whereas we often find Pompeius rather than Pompey, Antonius rather than Antony, we seldom find Iulius rather than Julius, perhaps due to a matter of pronunciation. As for his adoptive son and great-nephew, that brought yet another issue, as he often appears as Octavius, Octavian, Gaius Julius and Augustus. We dismissed the latter, as it is more of a title than a name, and as it has little to no relevance in a significant portion of the period and events in cause throughout our work; to avoid ambiguity, he shall be addressed as Octauianus.

Lastly, a short note regarding the Greek and Latin quotes. Most of the concepts and terms are presented in the Nominative case, which is not always the one in which they appear in Ancient sources. Whenever it seems justifiable to facilitate further reading and

studying, words will be presented in the original case/verb tense which originally appears in the source. These situations, as well as direct quotation from ancient texts, will appear underlined.

In what regards translations, even when the original bibliography has presented it otherwise, we will attempt to preserve, as much as possible, the original spelling. In all writings aside from Medieval, the Latin presented in our work will use «u» rather than «v» and «i» rather than «j» when presenting quotes from ancient authors. These are choices made towards creating a balance between clarity of interpretation and historical accuracy.

These points being said, what remains for this introductory note is to present with clarity the questions which we will attempt to see answered, and to explain our intention regarding this work. Regarding the former:

1. How was the structure of command within the Roman navy?

2. Was there evolution within this structure throughout the 1st century BCE?

3. Which were the preferences of Roman commanders regarding the management of fluvial and coastal resources?

4. Was there a shift in fighting techniques in what regards naval power? 5. How were ancient ships like in terms of shape, design and construction? 6. What physical evidence do we have of ancient ships?

7. What is the interpretation one can have of transport and warships? 8. Which materials were used in ancient ships?

9. How was communication processed within a fleet?

10. Was there an evolution in ship-type preference throughout the century in cause? 11. What was the general outline of an ancient harbour of this period?

12. What were the first harbours of Rome and how do they connect? 13. How does Rome’s relation with ancient harbours evolve?

14. Which materials were used in ancient harbours and which archaeological evidence do we have of their structures?

15. How did the notion of Mare Nostrum evolve into the Roman thought? 16. Was the Mediterranean truly a Mare Nostrum for Rome?

34

The main intention of this work is not, however, to provide definite answers, as we realise the immense difficulties which are still in the way, both technological, bibliographical and archaeological. More important than replying to them is to raise them, following the line of the recent studies which are attempting to shift the traditional paradigm of Rome’s presence at sea. Instead of attempting to reply to all the questions, our prospect is that through this work these lines can continue to be explored, that it can be a contribute towards raising more future questionnaire and debate, and that Rome’s role at sea, particularly regarding its construction and definition throughout the Republican period, can become a subject which is target of further study, further investigation and further knowledge.

36

I

I. DE BELLO NAVALE

Naval battles, from foreign concept to Roman entertainment. Painting by Ulpiano Checa, 18933.

1. Commanders at sea: the problematic

Our analysis of the problematics surrounding Rome’s relation with the sea begins with the observation of the human component of the fleet, without which it cannot function. The Roman navy is a part of its military forces and, as such, must have had an organised hierarchy in which, in parallel with the land army, the commanders-in-chief would rely on their subordinates to assure a proper functioning of all units. The purposes of this chapter are thus, firstly, to understand the organisation of the Roman navy’s command hierarchy in the period comprehended between 107 BCE and 15 CE and, secondly, to verify the course of action taken by the commanders during practical situations of naval activity at sea and in rivers. A study of this nature is accompanied by a series of issues, amongst which the elusiveness of source-derived information is but the smallest. Rome’s frequent reliance on its allies to supply its fleets, the lesser material regarding the Roman fleet for the period following the ending of the First Punic War4 until the Mithridatic

3 Picture from Wikimedia Commons ({{PD-US-expired}}).

4 It is not this study’s purpose to analyse the period between the 3rd century BCE and the late 2nd century. However, it should be stated that, in fact, Rome seems to have had a navy throughout this period, and to have used it, in the least, for transport purposes. One could point out, for instance, Book III of Polybius, where there are several mentions of ships being used during the Second Punic War.

38

Wars, the frequent inclusion of most naval encounters as a secondary occurrence in the wider set of war by ancient sources, and the general confusion which may derive from the difference or coincidence between the terms used by Greek and Latin sources are some of the problems the researcher will find when attempting to draw conclusions on this field.

Lionel Casson attempted to list the naval officers of ancient Greek and Roman fleets. In his work Ships and Seamanship in the Ancient World, which remains one of the key studies in this field, he dedicates a chapter to analysing the evolution of «Officers and Men». The author determined that the earliest and most important charges would be those of the «kybernetes» (the steersman), the «keleustes» (the individual who coordinated the rowers) and the «prorates» (the lookouts, who stood watch). As ships and navies developed, new naval stations would have joined the earliest three. During the Hellenistic Age, for instance, «the steady progress in design and armament (…) was paralleled by a marked development in the man-of-war’s complement». The author draws most of his information for the period between the third to the first century BCE from Rhodes. There is now a «trierarchos», the «captain» in the Rhodian navy, the «epiplous», which he calls a «vice-captain», the «grammateus», which he refers to as a «secretary and treasurer», a «pentekontarchos», which would be an «assistant rowing officer» with light administrative functions, and the already existent charges of «kybernetes», «prorates» and «keleustes»5.

Casson, however, does not consider that Rome had a standing navy prior to the imperial age, which is something this study will discuss:

«When it came to fighting personnel, Rome abandoned Greek models, for here she had a well-developed tradition of her own to follow – that of the army. The Roman standing navy, founded by Augustus toward the end of the first century B.C., was a late and junior branch of the military establishment. And so, it was a natural move to arrange the fighting component on a galley according to a pattern taken from the army. But Rome went even further: she grafted onto each ship a complete army organisation. Every crew was treated as a century of the Roman army».

The author describes Rome as adopting «the traditional Greek organization» but combining «with it some important typically Roman features». Casson underlines the «trierarchus», the «gubernator» (equivalent to a «kybernetes»), the «proreta», the «celeusta» and the «pausarius» (the last two being «rowing officers»)6. This view is

5 Minor functions are also mentioned, such as the carpenters («naupegos»), the «iatros» (a physician), and a «kopodetes» (who was in charge of the oars), but they are not directly connected to commanding officers. 6 Casson [1971] 1995.