www.bjorl.org

Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Clinical

characteristics

of

patients

with

persistent

postural-perceptual

dizziness

夽,夽夽

Roseli

Saraiva

Moreira

Bittar

a,

Eliane

Maria

Dias

von

Söhsten

Lins

b,∗aDivisionofOtoneurology,HospitaldasClínicas,MedicalSchool,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(USP),CerqueiraCésar,SãoPaulo,SP,

Brazil

bDepartmentofOtorhinolaryngology,MedicalSchool,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(USP),CerqueiraCésar,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received17January2014;accepted24May2014 Availableonline6September2014

KEYWORDS

Anxiety; Depression; Dizziness; Comorbidity

Abstract

Introduction:Persistentpostural-perceptualdizzinessisthedizzinessthatlastsforoverthree monthswithnoclinicalexplanationforitspersistence.Thepatient’smotorresponsepattern presentschangesandmostpatientsmanifestsignificantanxiety.

Objective:To evaluate the clinical characteristics ofpatients with persistent postural and perceptualdizziness.

Methods:statisticalanalysisofclinicalaspectsofpatientswithpersistentpostural-perceptual dizziness.

Results:81patients,averageage:50.06±12.16years;female/maleratio:5.7/1;main rea-sonsfordizziness:visual stimuli(74%),bodymovements(52%),andsleepdeprivation(38%). Themostprevalentcomorbiditieswerehypercholesterolemia(31%),migraineheadaches(26%), carbohydratemetabolismdisorders(22%)andcervicalsyndrome(21%).DHI,State-TraitAnxiety Inventory---Trait,BeckDepressionInventory,andHospitalAnxietyandDepressionScale ques-tionnaireswerestatisticallydifferent(p<0.05)whencomparedtocontrols.68%demonstrated clinicalimprovementaftertreatmentwithserotoninreuptakeinhibitors.

Conclusion:Persistentpostural-perceptualdizzinessaffectsmorewomenthanmen,withahigh associatedprevalenceofmetabolicdisordersandmigraine.Questionnaireshelptoidentifythe predispositiontopersistentpostural-perceptualdizziness.Theprognosisisgoodwithadequate treatment.

© 2014Associac¸ãoBrasileira de Otorrinolaringologiae CirurgiaCérvico-Facial. Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:BittarRS,SohstenLinsEM.Clinicalcharacteristicsofpatientswithpersistentpostural-perceptualdizziness. BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2015;81:276---82.

夽夽Institution:HospitaldasClínicas,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo,CerqueiraCésar,SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil. ∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:elianesohsten@gmail.com(E.M.D.vonSöhstenLins). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.08.012

PALAVRAS-CHAVE

Ansiedade; Depressão; Tontura; Comorbidade

Caracterizac¸ãoclínicadospacientescomtonturapostural-perceptualpersistente (TPPP)

Resumo

Introduc¸ão: Adenominac¸ãotonturapostural-perceptualpersistente(TPPP)éatribuidaà ton-turaquesemantémpormaisde3mesesem pacientes,semqueexistajustificativaclínica paraasuapersistência.Amaioriadospacientespossuiperfilansiosoouexperimentaaltograu deansiedadenoiníciodossintomas.Opadrãoderespostamotoraapresenta-sealterado,com hipervigilânciaehipersensibilidadeaestímulosvisuaisedemovimento.

Objetivo: AvaliarascaracterísticasclínicasdepacientescomdiagnósticodeTPPP.

Método: AnálisedosaspectosclínicosdepacientesdoambulatóriodeTPPPequantificac¸ãodo perfilansiosooudepressivo.

Resultados: Foramavaliados81pacientes,commédiadeidadede50,06±12,16anos;relac¸ão mulher/homemde5,7/1;principaisgatilhosparatontura:estímulosvisuais(74%),movimentos corporais(52%)eprivac¸ãodesono(38%).Ascomorbidadesmaisprevalentesforam hipercoles-terolemia(31%),migrânea(26%),distúrbiosdometabolismodoac¸úcar(22%)esíndromecervical (21%).OsquestionáriosDHI,STAI-Trac¸o,BeckparadepressãoeHADSforamestatisticamente diferentes(P<0,05)entrepacientesecontroles.68%demelhoraclínicacomousodeinibidores darecaptac¸ãodaserotonina.

Conclusão:TPPPacometeprincipalmenteasmulheres,sendoaltaaassociac¸ãocomdistúrbios metabólicosemigrânea. Osquestionáriosauxiliamnaidentificac¸ãodapredisposic¸ãoàTPPP. Hábomprognósticocomotratamentoadequado.

©2014Associac¸ãoBrasileiradeOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.Publicado por ElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

The field of Otoneurology evolved considerably in recent decades, froma simple vestibulometric evaluation of the vestibule-ocularreflextoacomplexinvestigationofbalance andposture. Nevertheless,therearepatientswhoexhibit undiagnoseddizzinessnotexplainedbysomeotoneurologic disease,evenwiththehelpofthefullrangeofdiagnostic testsofferedtoday.Thetestspresentnormalresults;untila shorttimeago,thesepatientswerelabeledaspsychogenic. Psychiatric syndromes also do not explain the symptoms found intheseindividuals. In1986, Brandt1 described the

phobic postural vertigo (PPV), which still did not explain indetailtheoriginofsymptomsnorsuggestedanykindof treatment.Atthebeginningofthe21stcentury,Staaband RuckensteinrelatedphysicalsymptomsofPPVtobehavioral factors,inmay2013,itwasrenamedpersistentposturaland perceptualdizziness(PPPD)forcompatibilitywithDSM-5.2,3

PPPD isdefined asatype ofdizzinessthat persistsfor over three months with no identifiable etiology.3 This is

asomatoformdisorder,representinganinterfacebetween otoneurologyandpsychiatry.Apparently,patientswithPPPD presentaprofilethatpredisposestothepersistenceof dizzi-nessafteraneventofphysical oremotional illness.When thereis suchaprofile, thepostural stabilitymaintenance systembecomeshyper-reactivetomovement,especiallyin environmentswithhighvisualdemands.Fromthis sensitiv-ity,thereisan increaseintheriskof behavioraldisorders such as anxiety, phobias, and depression.4 Thus, PPPD

reflects the persistence of a vigilant pattern of posture control that was assumed during the acute phase of the disease.4

PPPD is a chronic condition that can last for months oryears,5---7 andischaracterizedby sixbasic aspects4:(1)

Persistent sway or instability not detectable on physical examination; (2) Worsening of symptoms in the standing position;(3)Worseningofsymptomswithheadmovements orwithcomplexvisualstimuli;(4)Presenceofillnessor emo-tionalshock at symptom onset4; (5) Concurrent diseases,

mainlythatgaverisetothesymptoms7;(6)Anxiety.

The association between dizziness and anxiety in otoneurological patients is attributed to neural inter-actions explained by neuroanatomy.2 These interactions

include connections between central-vestibular pathways andneuralnetworksofanxietyandfear.Thefunctional neu-rocircuitryofanxietyincludestheamygdala,insula,anterior cingulate,prefrontal cortex, superior frontal gyrus, para-cingulate,andinferiorfrontal gyrus. Thesestructures are closelylinkedtoemotion,andtheirdysfunctioncanresult in impaired neural processing, with consequent anxiety.8

Theidentificationoftheinterdependencebetween otoneu-rologic and psychiatric diseases becomes crucial in the prognosisofdizziness.9

Based on the concepts presented by Staab and Ruckenstein,9PPPDcanproducethreedifferent

manifesta-tions:(1)Psychogenic:anxietyisthesolecauseofdizziness; (2)Otogenic:anotoneurologicdiseaseactsasatriggerthat activatesthecircuitryofanxiety;(3)Interactive:an otoneu-rologicdiseasetriggersdizziness,whichinturnexacerbates pre-existinganxietysymptoms.Therearereportsdescribing thatthepersistenceofdizzinessis directlyrelatedtothe severityoftheinitialimbalanceandtotheanxiety gener-atedbybodilysensationsduringtheepisode.10Theanxiety

ThetherapeuticapproachtoPPPDtakesintoaccountsome basicprinciples.Thefirstisthecorrectidentificationofthe symptoms,followedbycounselingfor gooddietaryhabits, medication, vestibular rehabilitation, and psychotherapy. Vestibular rehabilitation is based on the identification of troublesomemovements andonthedemonstration tothe patientthatthefearoftheircarryingoutthesemovements isunfounded;thus,theclassicalprotocolsofadaptationand substitutiondonotapply.Cognitive-behavioraltherapy, per-formedduringabriefperiod,isthepsychotherapyofchoice. Thistreatmenthelpsthepatienttoidentifysituationsthat causedistress,allowingthechoiceofthemostsuitable reac-tionalbehavior.13 The use of psychometric testing aids in

psychiatricscreening andinthe assessmentof thedegree ofperceptionofdizziness-inducedharm.

The drugs of choice for this treatment are serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs); serotonin is the primary neu-rotransmitterfor thosepreviously describednuclei. These drugschangeandregulateneuralconductionthrough anxi-etycircuitsandcentralvestibularneuronsthatrespondto movement. With the proper use of SSRIs, a reduction of symptomscanbeobtainedinasmanyas70%ofindividuals, inapproximatelythreemonthsoftreatment.14

Theknowledge oftheclinicalfeaturesof patientswith PPPDallowsfortheestablishmentofacorrectdiagnosisand anappropriatetreatment.This articleaimtodescribethe mainclinicalfeaturesandtherapeuticresponses in outpa-tientswithadiagnosisofPPPD.

Methods

ThisstudyassessedpatientswhoattendedthePPPD outpa-tientclinicduringtheyearof2013.Thisclinicispartofthe PPPDresearchproject,approvedby theethicscommittee oftheinstitutionundernumber0411/10.

The sample consisted of 81 patients between 17 and 80years(meanage50.06±12.16years),12malesand55 females.Allparticipantssignedaninformedconsentform. In order tobe included in the PPPD outpatient clinic, the patient should have experienced persistent dizziness for over three months, with no identifiable causes for thesymptomatology, i.e., allcomorbidities (carbohydrate metabolic disorder, dyslipidemia, thyroid disorders, neck pain,heartdisease,bloodpressuredisorder,dysautonomia, canalithiasis,cupulolithiasis, anemia,andother dizziness-inducing disorders) were compensated. All patients were previouslyattendedtoandtreatedbyphysiciansatthe gen-eraloutpatientclinic.Allparticipantsweresubmittedtoa full oculographicexamination and serological tests;when clinically indicated, the participants were also submitted toacomputerizedrotationalpendulumtest,computerized dynamicposturography, evokedpotentialstest, and imag-ingstudies.Noneoftheotherspatientsdiseaseshasacause effectrelationship tothesymptomspresented. Then,the patientsfollowedaparticularroutineofinvestigation espe-ciallydevelopedforpatientswithPPPD.

Thecontrolgroupconsistedofpatientswhosedizziness ceasedwithinthreemonthswithouttheuseofpsychotropic drugs.Sertralineatadose of25---100mg/daywasthefirst pharmacologicaloption; it was replacedby paroxetine at a dose of 20---40mg/day in a few patients due to lack of

response after eight weeks of use or due to the emer-genceofsideeffects(increasedanxiety,sexualdysfunction, gastrointestinalorsleepdisorders).Patientswerereferred for psychotherapy and desensitizing, where desensitizing exercises i.e.,dizziness-inducingstimulifor agradualand progressivepracticeuntiltolerance,wereprescribed.

Patients were classified as responders, when they presentedcompleteresolutionofsymptoms;partial respon-ders,whentheypresentedsymptomaticimprovement,but withpersistenceofsomesymptoms;andnon-responders,if therewasnoperceptionofimprovement.

The control group consisted of only seven female vol-unteers, due to the difficulty of recruiting asymptomatic patients;thisgenderwaschosenforbeingthemost preva-lentintheotoneurologyoutpatientclinic.

The study and control groups responded to several psychometrictests,allpreviouslyvalidatedforBrazilian Por-tuguese.

Anamnesis

Duringtheadmissionanamnesis,fivekeypointswere evalu-ated:timeofonsetofsymptoms,symptomcharacteristics, circumstances in which the dizziness occurs, associated symptoms,underlyingdiseases,andpredisposingfactorsto dizziness.15,16

Physicalexamination

The following tests to investigate the oculovestibu-lar reflexes were performed: spontaneous and semi-spontaneousnystagmus,headshakingnystagmus,andhead impulsetest.Thepostural stabilitywasthenevaluatedby Romberg,Fukuda,andwalkingtests.

Questionnaires

DHI(Brazilian Portuguese version):17,18 comprises25

ques-tions, seven of which assess physical aspects; nine assess emotionalaspects;andnineassessfunctionalaspects.The maximumscore,suggestingahighoveralldizziness-induced damage,is100points.

State-TraitAnxietyInventory(STAI):19twoscalesof

self-assessmentconsistingof20itemseach,rangingfrom1to4. Thesescalesassessanxietyasatransitoryemotionalstate (STAI-E[state])orasapermanentcharacteristicofthe indi-vidual(STAI-T[trace]).20

BeckDepressionInventory(BDI):Theoriginalscale con-sistsof21items,rangingfrom0to3intermsofintensity.20

Forsampleswithoutadiagnosisofdepression,thefollowing intervals wereadopted:<15: normal;16---20:indicative of dysphoria;>20:indicativeofdepression.21

HospitalAnxietyandDepressionScale(HADS) (Brazilian Portugueseversion):22 aself-reportscale withsevenitems

Table1 Samplecharacterizationinrelationtogenderand age.

Gender n Age(mean±DP) p

Male 12 49.41±10.43 Female 69 52.32±12.5

Total 81 50.06±12.16 0.41

Table2 Maintriggersintheonsetofsymptomsof persis-tentposturalandperceptualdizzinessnolugardechronic subjectivedizziness.

Trigger n Percentage Visualstimuli 60 74% Bodymovements 42 52% Sleepdeprivation 31 38% Crowding 21 26% Stress 20 25%

Neck 11 14%

Studyvariablesandstatisticalanalysis

The clinical characteristics of patients with PPPD are describedinTables1---5withpercentagesofprevalence.For thequestionnaires,comparativecalculationsweremadeby Studentt-test for researchparticipants, comparedto the control group, which consisted of asymptomatic patients fromthegeneraloutpatientclinic,withotoneurologic dis-easeandagoodresponsetotreatment.

Thelevelofsignificancewassetat5%(p=0.05).

Results

The gender and ages of the subjects in the study sam-ple areshown in Table 1. The mean age of subjects was 50.06±12.16years,withnostatisticallysignificant differ-encesbetweengenders(p=0.41).

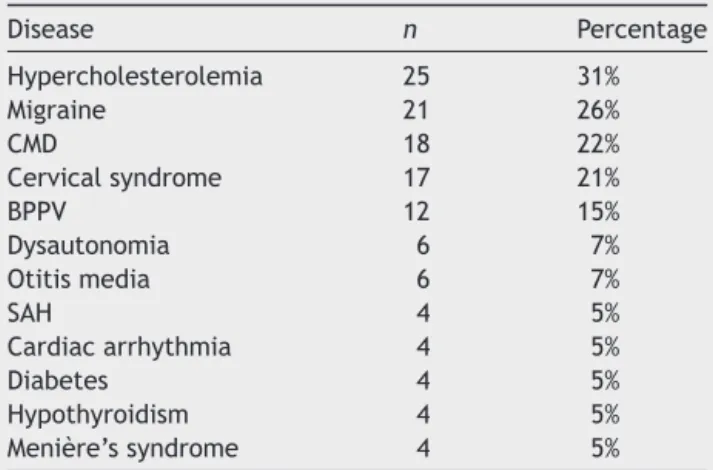

Table3 Comorbiditiesassociatedtopersistentperceptual andposturaldizzinessnolugardechronicsubjetivedizziness inthestudygroup.

Disease n Percentage Hypercholesterolemia 25 31% Migraine 21 26%

CMD 18 22%

Cervicalsyndrome 17 21% BPPV 12 15% Dysautonomia 6 7% Otitismedia 6 7%

SAH 4 5%

Cardiacarrhythmia 4 5% Diabetes 4 5% Hypothyroidism 4 5% Menière’ssyndrome 4 5%

CMD, carbohydrate metabolic disorders (hypoglycemia, intol-erance, and hyperinsulinemia); BPPV, benign paroxysmal positionalvertigo;SAH,systemicarterialhypertension.

WhenconsideringthetypeofPPPDaccordingtothe crite-ria defined by Staab and Ruckenstein,9 12 patients were

classifiedaspsychogenicPPPD(14.8%),20asotogenicPPPD (24.7%),and49asinteractivePPPD(60.5%).

Themaintriggersthatcausedtheabovementioned symp-toms aredescribed in Table 2. The threemost prevalent stimuliwere visual stimuli (74%), bodymovements (52%), andsleepdeprivation(38%).Somesubjectshadtwoormore triggersfortheirsymptoms,withamaximumofeight.

ThecomorbiditiesassociatedwithPPPDcanbeobserved in Table 3. Major diseases associated with PPPD were hypercholesterolemia(31%), migraine(26%),carbohydrate metabolicdisorder(22%),cervicalsyndrome(21%),benign paroxysmalpositionalvertigo(15%)dysautonomia(7%), dis-ordersof the middle ear(7%), hypertension (5%),cardiac arrhythmia (5%), diabetes (5%), hypothyroidism (5%), and Menière’s syndrome (5%). In addition to the described comorbidities, the following were found, accounting for less than 2% of prevalence: elderly unbalance syndrome, peripheralfacialpalsy,vestibularneuritis,epilepsy,sudden deafness, hepatitis C. Some patients had more than one comorbidityassociatedwithPPPD,withamaximum ofsix forthissample.

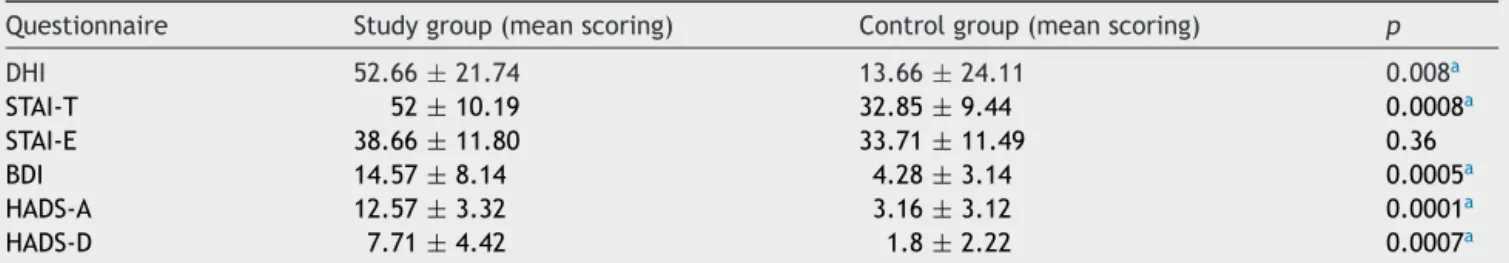

Regarding the formulated questionnaires, only STAI-E (p=0.36)showednosignificantdifferencebetweenpatients with a diagnosis of PPPD and those with no chronified dizziness after the vestibular event. All other question-naires showed significant differences among the groups: DHI(p=0.008),STAI-T(p=0.0008),BDI(p=0.0005),HADS-A (p=0.0001), andHADS-D(p=0.0007).The meanresponses obtainedfromthequestionnairesaredescribedinTable4.

Regardingtheevaluationofresponsestopharmacological treatment withSSRIs, theresults can beseen inTable 5. Ofthe45treatedpatients,46%respondedsatisfactorilyto medication,22%hadpartialresponse,and31%exhibitedno benefit.

Discussion

PPPD is a relatively new diagnosis that involves the vestibular-thalamicpathways, responsible for body move-ment awareness.23,24 The predisposition to sensitivity of

the structures involved in the connections between the vestibular-thalamicpathways andthecircuitryresponsible foranxietyandfeardeterminesymptomonset.Thisdisease isattheinterfacebetweenotoneurologyandpsychiatry,and thepatienthasnormalvestibularreflexes,while maintain-inga vigilant pattern of posturalcontrol. This is a highly distressingconditionforthepatient,whowillseekmultiple physicians andwill be submitted toseveral tests without findinganswerstohis/hersymptoms.

Themeanageofthestudygroupdidnotdifferfromthe recentliterature.25Inthepresentsample,themeanagedid

notdifferbetweengenders,butcomprisedahighernumber offemales,ataproportionof5.7:1.Recentpopulation sur-veyinthecityofSãoPauloconfirmsthehighprevalenceof dizzinessinfemales,inaratioof1.67:1,especiallyinthe agegroupbetween46and55years.26Thehigherprevalence

Table4 Responsestoquestionnairesformulatedforpatientswithchronicsubjectivedizziness(studygroup)andpatientswho didnotexhibitedcronificationoftheirdizzinessafteravestibularevent(controlgroup).

Questionnaire Studygroup(meanscoring) Controlgroup(meanscoring) p

DHI 52.66±21.74 13.66±24.11 0.008a

STAI-T 52±10.19 32.85±9.44 0.0008a

STAI-E 38.66±11.80 33.71±11.49 0.36

BDI 14.57±8.14 4.28±3.14 0.0005a

HADS-A 12.57±3.32 3.16±3.12 0.0001a

HADS-D 7.71±4.42 1.8±2.22 0.0007a

STAI-T,State-TraitAnxietyInventory ---Trait;STAI-E,State-TraitAnxietyInventory---State; BDI,Beck DepressionInventory;HADS-A, HospitalAnxietyandDepressionScale---Anxiety;HADS-D,HospitalAnxietyandDepressionScale---Depression.

aStatisticallysignificantdifferencebetweengroups.

peaksofmigraine.27,28StaabandRuckensteinalsoobserved

afemaledominance,witharatioof2:1.29Duetothehigher

prevalenceofPPPDinwomen,theoutpatientclinicwas ini-tiallyonlyforwomen.Theauthorsbelievethatthehigher number of women in relation to literature data occurred because,forinstitutionalreasons,thisparticularoutpatient clinicadmittedonly womenatthe beginningofits opera-tion.

According to the descriptions of Staab,9 PPPD can be

divided into three types: interactive, otogenic, or psy-chogenic. In the present sample, 60.5% of patients were classifiedasinteractive,24.7%asotogenic,andonly14.8% aspsychogenicCSD.Thesedatasuggestthatapproximately 75%(60.5+14.8)ofthepresentpatientshadatypically anx-iousprofile before developing their symptoms. Staab and Ruckensteinalsoreportedahighprevalenceofanxiety dis-ordersin60%oftheirpatientswithPPPD.29 Panicdisorder

prevailedinpatientswithpsychogenicform,whereas gen-eralizedanxiety disorderwasmorecommonininteractive PPPD,and mild anxiety symptoms weremore common in theotogenicform.29Theseobservationshighlighttheneed

forpsychiatricsupportforthesepatients.Thepartnership betweenpsychiatryandotoneurologybecomescriticalfora goodtreatment ofpatientswhopresentanomalousneural transmissionof connectionsbetween the vestibular path-waysandthecircuitryofvigilanceandfear.

RegardingthetriggersforPPPDcrisis,visualstimuliwas observedasatrigger in74%ofindividuals,comprisingthe 26%of subjectswhoreportedsymptomswhenin crowded places.Thesepatientsappeartopresentvisualdependency andatendencytorelymoreonvisualcuesthaninvestibular andsomatosensoryafferents forthe maintenanceoftheir posture.Forreasonsstillunknown,anxious patientsoften developvisualdependency.12Thesecondtrigger,inorderof

frequency,arebodymovements,asdescribedinthe litera-ture.Thehighlevelofanxietyexperiencedbythesepatients

Table5 Responseofpatientswithadiagnosisofchronic subjectivedizzinesspharmacologicallytreatedwithSSRIs. ResponsetoSSRIs n Percentage

Yes 21 46%

Partial 10 22%

No 14 31%

Total 45 100%

leadtoanelevatedmuscletensionandstiffnessintheneck, toavoid movements that causethe uncomfortable sensa-tions of instability andfear.30 Fromthis perspective, it is

easytounderstandthehighprevalenceofcervicalsyndrome (21%) and neck pain as a trigger for their symptoms. An interestingfact issleepdeprivation,functioningasa trig-ger for the symptoms of PPPD in 38% of cases, together withstressin25%ofthem.Stressactsasatriggerfor sen-sitizing theneural pathways responsiblefor thereactions ofvigilance.Aspreviouslymentioned,PPPDmainlyaffects womenbetweenthefourthandfifthdecadesoflife,atthe climacterictime,whichisthepeakincidenceofmigraine. ThemaintriggersofPPPDareexactlythesameasthosefor migraineattacks:visualconflict,head movements,stress, sleepdeprivation.27,28Thesimilarityofsymptomsraisesthe

questionof whetherthereisan interdependencebetween PPPD,migraine, andmetabolic andhormonaldysfunction. Infact, thethreemostfrequent comorbiditiesin patients withPPPDaredyslipidemia(31%),migraine(26%),and car-bohydratemetabolicdisorders(22%).StaabandRuckenstein observedaprevalenceof16.5%ofmigraineinpatientswith PPPD.29

Regarding DHI, the mean score from patients in this study (52.66±21.74) didnotdiffer fromtherecent liter-ature(59.8±19.3).PatientswithPPPDhadahigherscore when comparedto the controlgroup (p=0.008). This fig-ure allows for the conclusion that, compared to control subjects, the presented symptoms compromise the self-perceptionofbodybalanceandinterferewiththequalityof lifeofthesepatients.31 ForquestionsrelatingtoSTAI

ques-tionnaire, nosignificant differencebetweengroups in the STAI-E,which reproducesthestate of anxietyat thetime of consultation, was observed (p=0.36). However, when evaluating STAI-T, it was noted that the PPPD group pre-sentedasignificant differencewhencomparedtocontrols (p=0.0008).GoresteinandAndrade20 classifiedSTAIscores

<33aslow;between33and49,moderate; and>49, high. Eagger etal.32 observed a STAI-E value of 43.5

anxiousduringtheirclinicalvisit,butdoexhibitanxietyas acharacteristictraitoftheirpersonality.The anxiety pat-ternaffectstheassessmentofposturalchallenges,andthe patientassumeshigh-riskcontrolstrategiesformovements of low demand, changing their gait and posture because ofhis/herhypervigilance.Thehighertheanxietytrait,the greaterthefearofposturalchallengesandthemore exag-geratedthecorrectivestrategies.14

TheBDIreflectsthedegreeofdepressioninthepatient evaluated. Ascoreof15pointsonthescale isconsidered normal,andpatientswhoscorebetween16and20points are considered as dysphoric (i.e., with a decreased level of humor, but not depression). In the present sample, a significantdifferencewasobservedbetweenPPPDand con-trol groups (p=0.0005). The average for the PPPD group (14.57±8.14)characterized most subjectsasnormal,but thehighstandarddeviationofthesampleshowsthatthere isagreatertendencyforadepressedmoodinpatients,when comparedtocontrols.20

Regarding HADS, the present results are in agreement withthoseintheliterature.Staabetal.foundanaverage of 10.9±3for HADS-A and of8.1±4.4 for HADS-D.25 The

presentsample hadan averagescoreof12.57±3.32 (nor-mal<8)forHADS-Aand7.71±4.42(normal<8)forHADS-D. Bothresponses differsignificantly from the control group (p=0.0001andp=0.0007,respectively),demonstratingthat PPPDpatientshavechangeswithintheanxietyand depres-sionarea,comparedtotheasymptomaticpopulation.These values,however,donotcharacterizeindividualswithPPPD asdepressive,sincethescoringfordepressionisborderline. However,theHADS-Awashigher,justalittleabovethelimit acceptedfornormality,againcharacterizingthesepatients asanxious.

According to literature, the response to SSRIs stays around70%to75%.14,33Thepresentdatadonotdifferfrom

publishedreports,andthetreatmentproducessatisfactory resultsin46%ofpatients,withpartialresultsin22%ofthem. Thesumofthepositiveresponsesreached68%---aspectrum expectedforthepopulationofpatientswithPPPD.

Finally, the present experience with patients of PPPD show features very close to the international literature reports,andbringstolightmanyaspectsstilllittleknown tootorhinolaryngologists.Sincethis is agroup of somato-formpatients,theassociationbetweensomaticandpsychic evaluationiscrucialforabetterresolutionofthesymptoms.

Conclusion

PPPD is a dysfunction generated by psychic and somatic interactions,whichaffectsmorewomeninthemenopausal age group,withhigh association withmetabolic disorders and migraine. The main triggers of PPPD are visual con-flict,head movements,stress, andsleepdeprivation.The questionnaireshelpintheidentificationofpredispositionto thisdisease.An adequatetherapy conferstoPPPDagood prognosis, with improvements observed in almost 70% of patients.

Funding

ThisstudywasconductedbyFAPESP(Fundac¸ãodeAmparo àPesquisadoEstadodeSãoPaulo).

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.BrandtT.Phobicposturalvertigo.Neurology.1996;46:1515---9. 2.StaabJP.Chronicdizziness:theinterfacebetweenpsychiatry

andneuro-otology.CurrOpinNeurol.2006;19:41---8.

3.Staab JP. Assessment and management of psychological problems in the dizzy patient. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2006;12:189---213.

4.StaabJP.Chronicsubjectivedizziness;reviewarticle. Contin-uum(MinneapMinn).2012;18:1118---41.

5.HuppertD,StruppM,RettingerN,HechtJ,BrandtT.Phobic posturalvertigo---alongtermfollowup(5to15years)of106 patients.JNeurol.2005;252:564---9.

6.Kapfhammer HP, MayerC, Hock U, Huppert D,Dieterich M, BrandtT.Courseofillnessinphobicposturalvertigo.Acta Neu-rolScand.1997;95:23---8.

7.Staab J, Eggers S, Neff B.Validation ofa clinical syndrome of persistent dizzinessand unsteadiness. Abstractsfrom the XXVIBáránySocietyMeeting,Reykjavik,Iceland.2010;18---21. JVestibRes.2010;20:172---3.

8.Paulus MP. The role of neuroimaging for the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety. 2008;25: 348---56.

9.StaabJP,RuckensteinMJ.Whichcomesfirst?Psychogenic dizzi-nessversusotogenicanxiety.Laryngoscope.2003:113. 10.HeinrichsN,EdlerC,EskensS,MielczarekMM,MoschnerC.

Pre-dictingcontinueddizzinessafteranacuteperipheralvestibular disorder.PsychosomMed.2007;69:700---7.

11.StaabJP,BalabanCD,FurmanJM.Threatassessmentand loco-motion:clinicalapplicationsofanintegratedmodelofanxiety andposturalcontrol.SeminNeurol.2013;33:297---306. 12.StaabJP.Theinfluenceofanxietyonocularmotorcontroland

gaze,Review.CurrOpinNeurol.2014;27:118---24.

13.MahoneyAEJ,EdelmanS,CremerPD.Cognitivebehavior ther-apy for chronic subjective dizziness: longer-term gains and predictorsofdisability.AmJOtolaryngol.2013:115---20. 14.StaabJP,Ruckenstein MJ,AmsterdamJD.Aprospective trial

of sertraline for chronic subjective dizziness. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1637---41.

15.BalowRW,HonrubiaV.ThehistoryofthedizzypatientinClinical NeurophysiologyoftheVestibularSystem.2nded.OxfordPress; 2001.p.111---31.

16.TusaRJ.Dizziness.MedClinNorthAm.2009;93:263---71. 17.Garcia FV, Luzio CS, Benzinno TA, Veiga UG. Validac¸ão e

adaptac¸ão do Dizzness Handicap Inventory para a língua e populac¸ãoportuguesadePortugal.ActaORLTécnicasem Otor-rinolaringologiaEdic¸ão.2008;2.

18.Castro ASO, Gazzola JM, Natour J, Gananc¸a FF. Versão BrasileiradoDizzinessHandicapInventoryPró-fono.Revistade Atualizac¸ãoCientífica.2007;n.1:97---104.

19.SpielbergerCD,GorsuchRL,LusheneRE.Manualforthe Strait-TraitAnxietyInventory.PaloAlto,CA:ConsultingPsychologists Press;1970.

20.Gorenstein C,Andrade L. Validation of aPortuguese version oftheBeckDepressionInventoryand theStateTraitAnxiety InventoryinBraziliansubjects.BrazJMedBiolRes.1996;29: 453---7.

21.KendallPC,HollonSD,BeckAT,HammenCL,IngramRE.Issues and recommendations regarding useof the Beck Depression Inventory.CognitTherRes.1987;11:289---99.

23.BalohRW, Halmagyi GM.Disorders of thevestibular system. OxfordUniversityPress;1996.p.113---25[chapter10]. 24.Lopez C,BlankeO. Thethalamocorticalvestibularsystemin

animalsandhumans.BrainResRev.2011;67:119---46.

25.StaabJP,RobeDE,EggersSDZ,ShepardNT.Anxious,introverted personalitytraitsinpatientswithchronicsubjectivedizziness. JPsychosomRes.2014;76:80---3.

26.BittarRSM,OiticicaJ,BottinoMA,Gananc¸aFF,DimitrovR. Pop-ulationepidemiologicalstudyontheprevalenceofdizzinessin thecityofSãoPaulo.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2013;79:8---11. 27.Merikangas KR. Contributions of epidemiology to our

under-standingofmigraine.Headache.2013;53:230---46.

28.LoderE,RizzoliP,GolubJ.Hormonalmanagementofmigraine associatedwithmensesandthemenopause:aclinicalreview. Headache.2007;47:329---40.

29.Staab JP, Ruckestein MJ. Expanding the differential diagno-sis of chronic dizziness. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133:170---6.

30.HerdmanSJ.Reabilitac¸ãoVestibular.2nded.EditoraManole; 2002.p.312---24[chapter14].

31.Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The Development of the Dizzi-ness Handicap Inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:424---7.

32.EaggerS,LuxonLM,DaviesRA,CoelhoA,RonMA.Psychiatric morbidityinpatientswithperipheralvestibulardisorder:a clin-icalandneuro-otologicalstudy.JNeurolNeurosurgPsychiatry. 1992;55:383---7.