REVISTA

BRASILEIRA

DE

ANESTESIOLOGIA

PublicaçãoOficialdaSociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologiawww.sba.com.br

SCIENTIFIC

ARTICLE

Design

and

validation

of

an

oral

health

questionnaire

for

preoperative

anaesthetic

evaluation

夽

Gema

Ruíz-López

del

Prado

a,

Vendula

Blaya-Nováková

b,c,

Zuleika

Saz-Parkinson

c,d,

Óscar

Luis

Álvarez-Montero

e,f,

Alba

Ayala

g,

Maria

Fe

Mu˜

noz-Moreno

h,

Maria

João

Forjaz

g,∗aHospitalClínicoUniversitario,DepartamentodeMedicinaPreventivaySaludPública,Valladolid,Spain

bHospitalGeneralUniversitarioGregorioMara˜nón,ServiciodeMedicinaPreventivayGestióndeCalidad,Madrid,Spain cInstitutodeSaludCarlosIII,AgenciadeEvaluacióndeTecnologíasSanitarias,Madrid,Spain

dHospitalClínicoSanCarlos,InstitutodeInvestigaciónSanitaria,Madrid,Spain

eHospitalUniversitarioInfantaLeonor,DepartamentodeOtorrinolaringología,Madrid,Spain fHospitalUniversitarioPuertadeHierro,DepartamentodeOtorrinolaringología,Madrid,Spain gInstitutodeSaludCarlosIII,EscuelaNacionaldeSanidad,Madrid,Spain

hHospitalClínicoUniversitario,UnidaddeInvestigaciónBiomédica,Valladolid,Spain

Received20May2015;accepted17August2015 Availableonline21March2016

KEYWORDS Patientsafety; Dentalinjury; Oralhealth; Oralhygiene; Questionnaire

Abstract

Backgroundandobjectives: Dentalinjuriesincurredduringendotrachealintubationaremore

frequentinpatientswithpreviousoralpathology.Thestudyobjectivesweretodevelopanoral

healthquestionnaireforpreanaesthesiaevaluation,easytoapplyforpersonnelwithoutspecial

dentaltraining;andestablishacut-offvaluefordetectingpersonswithpoororalhealth.

Methods:Validationstudyofaself-administeredquestionnaire,designed accordingtoa

lit-eraturereviewandanexpertgroup’srecommendations.Thequestionnairewas appliedtoa

sampleofpatientsevaluatedinapreanaesthesiaconsultation.Raschanalysisofthe

question-nairepsychometricpropertiesincludedviability,acceptability,contentvalidityandreliability

ofthescale.

Results:Thesampleincluded115individuals, 50.4%ofmen,with amedianageof58years

(range:38---71).Thefinalanalysisof11itemspresentedaPersonSeparationIndexof0.861and

goodadjustmentofdatatotheRaschmodel.Thescalewasunidimensionalanditsitemswere

notbiasedbysex,ageornationality.Theoralhealthlinearmeasurepresentedgoodconstruct

validity.Thecut-offvaluewassetat52points.

夽

ThisworkshallbeattributedtotheDepartmentofPreventiveMedicineandPublicHealth,ClinicUniversityHospital,Valladolid,Spain, andNationalSchoolofPublicHealth,InstituteofHealthCarlosIII,Madrid,Spain.Theclinicalpartofthestudywascarriedoutatthe DepartmentofAnesthesiologyandResuscitation,InfantaLeonorUniversityHospital,Madrid,Spain.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:jforjaz@isciii.es(M.J.Forjaz). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjane.2015.08.007

Conclusions: Thequestionnaireshowedsufficientpsychometricpropertiestobeconsidereda

reliabletool,validformeasuringthestateoforalhealthinpreoperativeanaesthetic

evalua-tions.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Thisisan

openaccessarticleundertheCCBY-NC-NDlicense(

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Seguranc¸ado paciente; Lesãodentária; Saúdebucal; Higienebucal; Questionário

Projetoevalidac¸ãodeumquestionáriodesaúdeoralparaavaliac¸ãopré-anestésica nopré-operatório

Resumo

Justificativaeobjetivo: Aslesõesdentáriasqueocorremduranteaintubac¸ãotraquealsãomais

frequentesempacientescompatologiaoralprévia.Oobjetivodoestudofoidesenvolverum

questionáriodesaúdebucalparaavaliac¸ãonoperíodopré-anestesia,defácil aplicac¸ão por

pessoalsemformac¸ãoodontológica,eestabelecerum valorde corteparadetectarpessoas

commásaúdebucal.

Métodos: Estudodevalidac¸ãodeumquestionárioautoadministrado,projetadodeacordocom

umarevisãodaliteraturaerecomendac¸õesdeum grupodeespecialistas.Oquestionáriofoi

aplicadoaumaamostradepacientesavaliadosemumaconsultapré-anestesia.AanáliseRasch

daspropriedadespsicométricasdoquestionárioincluiuviabilidade,aceitabilidade,validadede

conteúdoeconfiabilidadedaescala.

Resultados: Aamostraincluiu115indivíduos,50,4%dehomens,comidademedianade58anos

(variac¸ão:38-71).Aanálisefinaldos11itensapresentouumíndicedeseparac¸ãodosindivíduos

de0,861eumbomajustedosdadosaomodelodeRasch.Aescalafoiunidimensionaleseus

itensnãoforaminfluenciadospelosexo,idadeounacionalidade.Amedidalineardasaúdebucal

apresentouboavalidadedeconstruto.Ovalordecortefoifixadoem52pontos.

Conclusões: Oquestionáriomostrou propriedades psicométricassuficientes para ser

consid-erado uma ferramentaconfiável,válida paramedir oestadodesaúdebucalnas avaliac¸ões

pré-anestesiaantesdaoperac¸ão.

©2016SociedadeBrasileiradeAnestesiologia.PublicadoporElsevierEditoraLtda.Este ´eum

artigo OpenAccess sobumalicenc¸aCCBY-NC-ND(

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Introduction

Damage to teeth and oral tissues is one of the most frequent complications of endotracheal intubation and general anaesthesia in general.1,2 The incidence varies

widely, with different studies reporting values between 1:4574 and 1:3 intubated patients.3---13 Previous dental

pathology,6,8,10,11generalanaesthesia,9,10laryngoscopy3and

difficult intubation4,6,8,11 have been commonly associated

withdentalinjuryduringananaestheticprocedurein obser-vationalstudies.

Dentalinjuriesasacomplicationofgeneralanaesthesia areafrequentsubjectofreviewarticles,recommendations and guidelines issued by scientific societies.14---17 Several

authors suggested specific charts for a systematic docu-mentation of the state of patients’ dentition before the interventionin ordertoavoid possiblelitigations,13,14,18---20

but little has been published about effective prevention strategies.

Perioperativedentalinjuriesseemtobemorerelatedto diseasesoftheoralstructuresthemselvesthantomedical errors during anaesthesia,11,21 dental injury risk

minimi-zation should therefore start with a careful oral health evaluationduringthepreanaesthesiaconsultation.Because

correctassessmentoforal healthmaybedifficultfor per-sonnelwithout specialdentaltraining,6 andapplicationof

commonly recommended and often extensive oral health surveysmaybetime-consuming,wehavedecidedtodesign asimple guidancetoolfor evaluatingthe oral healthin a preanaesthesiaclinic.

Theprincipalobjectiveofourstudywastodevelopa self-administeredquestionnaireoforalhealthandoralhygiene habitsforpatientsundergoinggeneralanaesthesiaand vali-dateitusingaRaschanalysis.Thesecondaryobjectiveofthe studywastoestablishacut-offvaluefordetectingpersons withpoororalhealth.

Methods

ThestudywasapprovedbytheInstitutionalReviewBoardin linewiththeprovisionsoftheDeclarationofHelsinki,and writteninformedconsentwasobtainedfromallsubjects.

Studypopulation

procedureingeneralanaesthesiainthishospitalare eval-uatedin this clinic. Minors, patients with legal guardians andpatientswithintellectuallimitationswhichmayimpede correctunderstandingofthequestionnairewereexcluded.

Questionnairedesign

A short, self-administered questionnaire was designed basedona review of literature identifiedthrougha Med-line search (using MeSH terms ‘‘oral health’’, ‘‘tooth loss/epidemiology’’and‘‘periodontaldiseases’’)and opin-ions of a panel of experts consisting of four members (maxillofacial surgeon, dentist, otorhinolaryngologist and anaesthesiologist) whohelped to adapt the questionnaire foritsuseinthepreanaesthesiaclinic.

Thequestionnaireoriginallyconsistedof23items identi-fiedthroughthebibliographicsearch.Theresponsescaleof theitemswasLikert-type,withresponseoptionsbasedon frequency.Eachresponsewasgivenascore,whichaddedup toamaximumof100pointsintotal.Theagewascategorized into8groups(18---25,26---35,36---45,46---55,56---65,66---75, 76---85, >85 years), assigning incremental values of 5---40 pointstoeachoneofthem.Thebodymassindex(BMI)was categorizedinto 3 groups (<25, 25---30, >30kg/m2). Infor-mationabouthabitsconsidereddetrimentalfororalhealth (smoking, alcohol consumption), medication and other diseases(diabetes,osteoporosis,liverdisease,HIV,cancer or rheumatoid arthritis)wasalsoadded. The initial ques-tionnairewasanalysed independently by each oneof the expertsbasedontheirknowledgeandclinicalexperience.

Thepanelrecommendedexcludingthequestion‘‘howdo yourateyour oralhealth?’’asitwasconsidered tobetoo subjectiveand relatedmoretothequalityof lifeaspects (aesthetics and self-perception) rather than to true oral habits.Bisphosphonateswereaddedtothelistofharmful medicationsbecauseof itsassociationwithosteonecrosis. BMIdatareplacedthequestion‘‘areyouobese?’’asamore objectivemeasure.Theexpertsconsidered itnecessary to askabouttoothmobility,gumbleeding,toothacheand miss-ingteeth,astheseareunequivocalsignsofpoororalhealth. Thefinalversionofthequestionnaireincluded18items grouped into three dimensions. The general information groupconsistedoffiveitems;13itemswererelated exclu-sivelywithoralhealth:eightoftheseaddressedoralhealth and oral health habits and five items were dedicated to habitsandconcomitant diseaseswhich areknowntohave a negativeeffect on oral health. Higher scores indicated worseoralhealth.

The questionnaire wasfirst pilot-tested on10 patients andthenappliedtothestudypopulation.Thepatients com-pleted the questionnaire in the waiting room before the preanaesthesia assessment. The anaesthesiologist, previ-ouslytrainedinoralexplorationbyadentist,evaluatedthe stateoforalhealthandclassifieditasgood,fairorpoor.This oralexplorationincluded directobservation witha dental mirror,periodontalprobing,toothmobilityexaminationand calculationofthedecayed,missing,filledteeth(DMF)index. Aglobalratingoforalhealth(good,fair,poor)wasprovided bytheanaesthesiologistandthedentist,whoexaminedthe patientsindependentlyaftertheanaesthesiologist.

Statisticalanalysis

TheRaschmodelwasusedtotestthemeasurement proper-tiesoftheoralhealthquestionnaire.22TheRaschanalysisis

themostcurrentvalidationscalemethodwhichfollowsan additiveprocessofjointmeasurementofpersonsanditems in the same dimension or construct.23 Information about

Rasch analysis,explainedina friendlyway,maybefound elsewhere.23First,responsecategoriesofsomeoftheitems

werecollapsedwherenecessaryinordertoensurethatthe categorythresholds(pointofequalprobabilityofresponse betweentwoneighbouringcategories)wereordered.Items with standardized residuals above ±2.5 were eliminated. A non-significant chi-squareof the item-trait interaction, withBonferronicorrection,indicatedagoodfittotheRasch model. The reliability was examined through the Person SeparationIndex(PSI)withthecriterionof≥0.7forgroup comparisonsand≥0.85forindividualcomparisons.23

Princi-palcomponentanalysisoftheresidualsandindependency

t-testwereusedtoensurethatallitemsofthescaleformed auniquedimension,withsignificantvaluesof<10%or the lowerconfidenceintervallimitofthebinomialof <0.05.24

Theitemsshouldbelocallyindependent,whichmeansthat correlationsbetweenstandardized residualsshouldnotbe high(criterionfixedat0.3).Theitemswerefreefrombias by sex, age (by median: ≤58, >58 years) and nationality (Spanish,other)ifthep-valueoftheBonferronicorrection associatedtotheanalysisofvariance(ANOVA)ofdifferential itemfunctioning(DIF)wasnotsignificant.Ifmorethanone itempresentedDIFforacertainfactor,atop-down purifi-cation analysiswasperformedandtheimpureitems(with a bias) were subject to a DIF analysis, because if differ-entitemsactinoppositedirections,theDIFgetscancelled out.25

Afterobtaininga fit totheRasch model,psychometric properties(normality,acceptabilityandconstructvalidity) ofthelinearscalewereexamined.TheKolmogorov---Smirnov test wasusedtoverifythenormal distributionofthe lin-earmeasure.Dataacceptabilitywasanalysedthroughthe differencesbetweenmeanandmedian(arbitrarystandard of ≤10% of the maximum score)26 and floor and ceiling

effects(below15%).27Theknowngroupsvaliditywas

exam-ined through the Student’s t-test and ANOVA in order to examinesignificant differencesinoralhealth bysex, age, obesity,nationalityandlevelofeducation.Criterion valid-ity was established by comparing the oral health linear measure with the results of dental examination (good, fair, poor), using ANOVA. The inter-observer concordance in the rating of oral health between the anaesthesiol-ogist and the dentist was assessed through the kappa index.

Finally,aReceiverOperatingCharacteristic(ROC)curve was calculated in order to identify a cut-off value for detecting poor oral health. The results of the oral cavity examination (poorvs.good/fairoral health)wereusedas the criterion variable.Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negativepredictivevalues(PPV,NPV)andpositiveand neg-ative likelihoodratios (LR+,LR−)were calculatedfor the selectedcut-offvalue.

The Rasch analysiswas performed withthe RUMM2030 program,28 andIBMSPSSStatisticsversion19.0(IBMCorp.,

Results

Theadministeredversionofthequestionnaireincluded 18 items,5aboutgeneralinformationand13concerningoral health.Theestimatedtimeforcompletingthe18-item ques-tionnairerangedbetween1.5and2min.Theinter-observer concordance between the oral-cavity examination by the anaesthesiologist anddentistwasfoundtobesatisfactory after3daysoftraining(kappaindex=0.78;standarderror, SE=0.18).

Three ofthe118patients whowereapproachedin the preanaesthesiaclinicrefusedtoparticipateduetoimpaired visionandinabilitytowrite.Allquestionnairesanalysedhad 100% of the itemscompleted. Of the 115 patients,50.4% were men, witha mean age of 55.1 (standard deviation, SD=19.1;range:18---88)years.Ninety-threepatientswere Spanish (80.9%). The mean BMI was 26.8kg/m2; 24 per-sons were obese (BMI >30kg/m2; 20.9%). As for thelevel ofeducation,68patientshadlessthansecondaryeducation (59.2%).Oralhealthwasconsideredasgoodin32patients (28.1%);fairandpoor oralhealth wasfound in37 (32.5%) and45patients(39.5%),respectively(Table1).

The first analysis of the 13 oral health items did not show good adjustment of data to the Rasch model. Two itemswere recoded:lastvisittothedentist (‘‘<6months ago’’and‘‘between6monthsand1yearago’’were com-bined) and gum bleeding frequency (‘‘very often’’ and ‘‘always’’ were combined). The items concerning drink-ing alcohol and smoking were eliminated because they measuredanotherconstruct(standardizedresiduals >2.5).

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of the patient sample (n=115).

Mean± SD;n(%)

Age 55.1± 19.1

Sex

Male 58(50.4)

Female 57(49.6)

BMI(kg/m2) 26.8±4.2

BMIcategorized(kg/m2)

<25 41(35.7)

25---30 51(44.3)

>30 23(20)

Nationality

Spanish 93(80.9)

Other 22(19.1)

Educationlevel

None 31(27.0)

Primarystudies 37(32.2)

Secondarystudies 27(23.5)

Universitystudies 20(17.4)

Oralhealth(basedonanoralexamination)

Good 32(28.1)

Fair 37(32.5)

Poor 45(39.5)

SD,standarddeviation;BMI,bodymassindex.

Location 3.0 2.0 TMOB. 3 TMOB. 2 TMOB. 1 RVD. 3 TBF. 2 PAIN. 1 LVD. 2 FMU. 3 FMU. 2 FMU. 1 TBF. 1 TMISS. 1 RVD. 1 GBF. 1 LVD. 1 TMISS. 3 DIS. 1 PAIN. 3

PAIN. 2 TBF. 3

RVD. 2 TMISS. 2 DIABE. 1 MEDIC. 1 GBF. 2 × × ××××××× ×××× × × × × × ×× × × × × × × × × × × ×× × × × × × × ×× × × × × × × × ×× × × × × × × × × ×× × × × × × × × ×× × × ×× ××× ××× × × × × = ×× ×× × × × × ×× × × × ×× ××××× × ××× × × × ×× × × ×× × 1.0 0.0 –1.0 –2.0 –3.0 –4.0 –5.0 person –6.0

Persons Items [uncentralised thresholds]

1

Figure1 Person-item thresholddistribution,inlogits(final

Raschmodel).

(DIABE,Diabetes;DIS,Diseases;FMU,Frequencyofmouthwash

use;GBF,Gumbleedingfrequency;MEDIC,Medication;LVD,Last

visittothedentist;PAIN,Painonchewing;RVD,Reasonfor

vis-itingthedentist;TBF,Toothbrushingfrequency;TMISS,Number

ofmissingteeth;TMOB,Toothmobility).

Analysis of the remaining 11 items presented good reli-ability (PSI=0.861) and good adjustment of data to the model(2(44)=64.168;p=0.025),withfitstatisticsof0.027

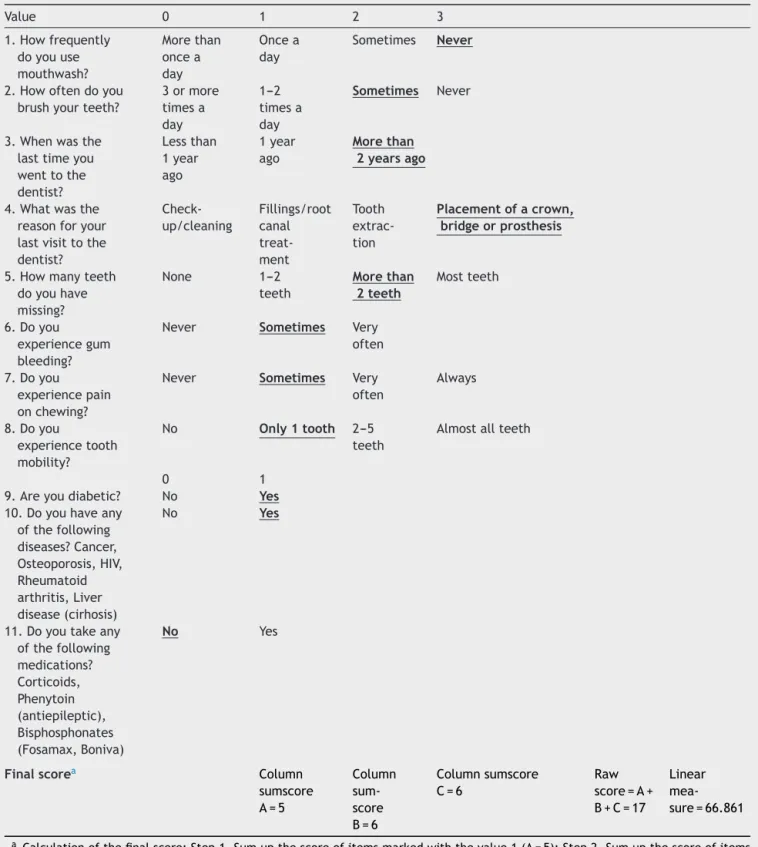

(SD=1.248)fortheitemsand−0.196(SD=0.914)for person-fit.Table2presentsthefinalversionofthequestionnaire, withascoring example.The fitstatisticsfor eachitemof thefinalmodelaresummarizedinTable3.

Theunidimensionality ofthescalewasconfirmed,with 7.83%significantt-testandanacceptableconfidence inter-valof thebinomial(95%confidenceinterval,CI95%=0.038; 0.118).The items ‘‘tooth brushingfrequency’’ and ‘‘pain onchewing’’ showedDIFby sexin opposite directions,so theDIFgotcancelledout(p=0.740).Theitem‘‘numberof missingteeth’’presentedDIFby age.NoitemshowedDIF bynationality.

Thethirdthresholdoftheitem‘‘toothmobilityinalmost allteeth’’represented the most severe oral health prob-lem, and the first threshold of the item ‘‘tooth brushing frequency≥3times/day’’representedtheleastsevereoral healthproblem(Fig.1).

Table2 Preanaesthesiaoralhealthevaluationquestionnairewithascoringexample.

Value 0 1 2 3

1.Howfrequently

doyouuse

mouthwash?

Morethan

oncea

day

Oncea

day

Sometimes Never

2.Howoftendoyou

brushyourteeth?

3ormore

timesa

day

1---2

timesa

day

Sometimes Never

3.Whenwasthe

lasttimeyou

wenttothe

dentist?

Lessthan

1year

ago

1year

ago

Morethan 2yearsago

4.Whatwasthe

reasonforyour

lastvisittothe dentist?

Check-up/cleaning

Fillings/root canal treat-ment

Tooth extrac-tion

Placementofacrown, bridgeorprosthesis

5.Howmanyteeth

doyouhave

missing?

None 1---2

teeth

Morethan 2teeth

Mostteeth

6.Doyou

experiencegum

bleeding?

Never Sometimes Very

often

7.Doyou

experiencepain

onchewing?

Never Sometimes Very

often

Always

8.Doyou

experiencetooth

mobility?

No Only1tooth 2---5 teeth

Almostallteeth

0 1

9.Areyoudiabetic? No Yes

10.Doyouhaveany

ofthefollowing

diseases?Cancer,

Osteoporosis,HIV,

Rheumatoid arthritis,Liver

disease(cirhosis)

No Yes

11.Doyoutakeany

ofthefollowing

medications? Corticoids, Phenytoin (antiepileptic), Bisphosphonates

(Fosamax,Boniva)

No Yes

Finalscorea Column

sumscore A=5

Column sum-score B=6

Columnsumscore C=6

Raw score=A+ B+C=17

Linear mea-sure=66.861

aCalculationofthefinalscore:Step1,Sumupthescoreofitemsmarkedwiththevalue1(A=5);Step2,Sumupthescoreofitems

markedwiththevalue2(B=6);Step3,Sumupthescoreofitemsmarkedwiththevalue3(C=6);Step4,Obtaintheinitialrawscore (A+B+C=17);Step5,Findthelinearmeasureassociatedwiththisrawscoreintheconversiontable(Table5).Inourexample,witha rawscoreof17,theassociatedlinearmeasureisof66.861ona0---100scale.

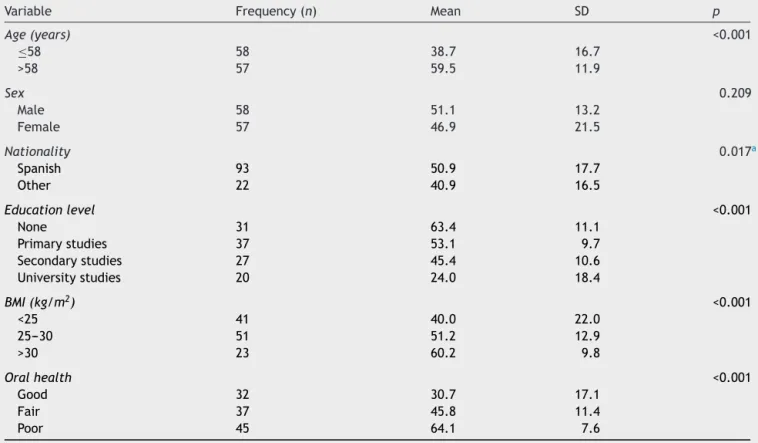

amean of 49.01(SD=17.85),mean---median differenceof 4.38%,and nofloor or ceilingeffects. Validity results are listedinTable5:oralhealthwassignificantlyworsein peo-ple over the age of 58 years and Spanish nationals, with

Table3 FitstatisticsfortheitemsofthefinalRaschmodel.

Item Difficulty SE Residuals 2(df=4) Probability

Frequencyofmouthwashuse −1.814 0.141 0.262 2.663 0.616

Toothbrushingfrequency −1.084 0.152 −1.478 6.170 0.187

Lastvisittothedentist −0.858 0.154 1.919 12.006 0.017

Reasonforvisitingthedentist −0.849 0.129 0.445 4.777 0.311

Numberofmissingteeth −0.495 0.132 −0.895 2.314 0.678

Gumbleedingfrequency 0.200 0.169 1.104 2.425 0.658

Diseases 0.551 0.236 −0.780 7.747 0.101

Painonchewing 0.840 0.141 1.339 5.732 0.220

Diabetes 0.999 0.252 −0.576 6.550 0.162

Toothmobility 1.098 0.145 −1.965 6.192 0.185

Medication 1.412 0.273 0.918 7.594 0.108

SE,standarderror;df,degreesoffreedom.

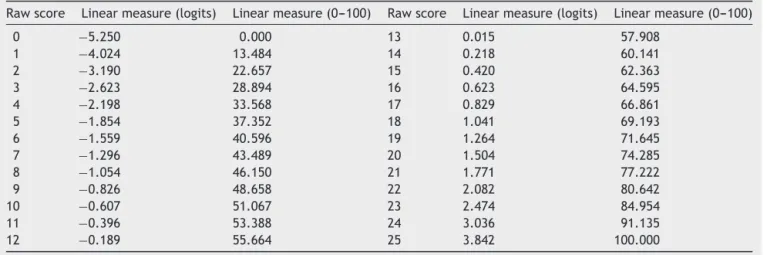

Table4 Conversiontablefromrawscorestothelinearmeasure.

Rawscore Linearmeasure(logits) Linearmeasure(0---100) Rawscore Linearmeasure(logits) Linearmeasure(0---100)

0 −5.250 0.000 13 0.015 57.908

1 −4.024 13.484 14 0.218 60.141

2 −3.190 22.657 15 0.420 62.363

3 −2.623 28.894 16 0.623 64.595

4 −2.198 33.568 17 0.829 66.861

5 −1.854 37.352 18 1.041 69.193

6 −1.559 40.596 19 1.264 71.645

7 −1.296 43.489 20 1.504 74.285

8 −1.054 46.150 21 1.771 77.222

9 −0.826 48.658 22 2.082 80.642

10 −0.607 51.067 23 2.474 84.954

11 −0.396 53.388 24 3.036 91.135

12 −0.189 55.664 25 3.842 100.000

health than the rest of the participants. The oral health linearmeasure increasedwithdentalexamination scores, followingasignificantlineartrend.

A ROCcurve wascalculated for thelinear scale, using thedentalexamination(poorvs.good/fairoral health)as variablecriterion,withanareaundercurve(AUC)of0.935 (SE=0.018,CI95%=0.92---0.99).Thecut-offvaluewassetat

52points(specificity=0.96;sensibility=0.86).ThePPV,NPV, LR+andLR−forthiscut-offvaluewere0.811,0.967,6.593 and0.052,respectively.

Discussion

The goal of the preanaesthesia evaluation is to detect patientswithanincreasedriskofcomplicationsanddesign effectivepreventionmeasures.The methodsusedfor pre-dictingpostoperativeproblemsfocusonthediseaseseverity, surgicalcomplexity,identificationofcomorbidities,and car-diacrisk,amongothers.Nevertheless,theconsequencesof oraldamagesecondarytoanaesthesiashouldnotbe under-estimatedasoral healthisimportantforagoodqualityof

life29,30 andfor goodhealth ingeneral.Ourobjectivewas

todesign ascreening toolfor assessingthe oral healthof patientsundergoingpreanaesthesiaevaluation.

Thequestionnaireisshort,easytounderstand, accept-abletopatientsandfeasibletoapplyintheclinicasitonly takesabout 2min tocomplete. The timing of the admin-istration --- after examination by the nurse while waiting tobeseenbytheanaesthesiologist---favourstheresponse andcompletionrateand increasespatients’awareness of thiscomplication.Theresponseoptionsaresimilar,butnot exactlythesameforeachquestion,whichpreventsthe cen-traltendencybias.Thecontentvaliditywassupportedbya panelofexperts.

The questionnaire is reliable,allowing for comparisons betweenindividuals.23 Furtherstudies thatadministerthe

questionnairein differentoccasions areneeded to evalu-atethetest---retestreliability.Theunidimensionalityofthe scale,representingasingleconstruct,permitsthescoreof alltheitemstobeaddedasalinearmeasure.Alinear mea-sureisimportantforinterventionstudiesandclinicaltrials asitallowsapplyingparametricstatisticaltests.

Almost all items were free from bias by sex and age. However,olderpatientsscoredhigherintheitem‘‘number of missing teeth’’, a fact previously documented.29 The

questionnairedisplayedadequatediscriminantvalidityand allowedastatisticaldifferentiationaccordingtowell-known oralhealthriskfactors:educationlevel31---33andBMI.34,35The

Table5 Descriptiveanalysisofdataandparametrictests(Student’st-testandANOVA)for thelinearmeasureofpoororal

healthaccordingtodifferentsociodemographicvariables.

Variable Frequency(n) Mean SD p

Age(years) <0.001

≤58 58 38.7 16.7

>58 57 59.5 11.9

Sex 0.209

Male 58 51.1 13.2

Female 57 46.9 21.5

Nationality 0.017a

Spanish 93 50.9 17.7

Other 22 40.9 16.5

Educationlevel <0.001

None 31 63.4 11.1

Primarystudies 37 53.1 9.7

Secondarystudies 27 45.4 10.6

Universitystudies 20 24.0 18.4

BMI(kg/m2) <0.001

<25 41 40.0 22.0

25---30 51 51.2 12.9

>30 23 60.2 9.8

Oralhealth <0.001

Good 32 30.7 17.1

Fair 37 45.8 11.4

Poor 45 64.1 7.6

SD,standarddeviation;BMI,bodymassindex.

aNon-significantwhenadjustedbyage.

comparedtothedentalexamination,butfurtherstudiesare neededtoexaminethepredictivevalidityofthe question-nairebycomparingthescoresobtainedwiththeintubation outcome.Onestudyreportedthat80%oftheinjurieswere classifiedas ‘‘unavoidable’’, which raises the question of theusefulnessofpredictingthisevent.Severalauthorshave foundthatitisdifficulttopredictdentaldamage,however, theyhavelookedatpredictingadifficultintubation8,13,19,36

ratherthantheriskofdentalinjuryitself.

Dentalinjuryhasnotbeendemonstratedtobemore fre-quentinemergencysurgeries8,10,12,13,19,36ortobeassociated

withthelevelofexperienceoftheanaesthesiologist.7,12,19

Severalmajorstudies have emphasizedthat dentalinjury wasup to50 times morelikely tooccur in patients with previousdentalpathologies,8,10whichsuggeststhatthe

per-sonalpredispositionis moreimportantthantheactionsof theanaesthesiologist.Thedesignofthequestionnairewas basedonthispremise.At thesametime,itisthebiggest limitationofourstudy:thereisnoevidenceuptodatethat beingaware of theoral health conditionsof the patients decreasestheriskofdentalinjuryduringananaesthetic pro-cedure. Acohort study of patients evaluatedthroughour questionnaireandfollowed-upfor theincidenceof dental injuryaftertheanaestheticprocedurewouldbenecessary toestimate itsutility in reducing dentaldamage. Still, a carefulexaminationoftheoralcavityisconsideredan inte-gralpartofthepreanaesthesiaevaluation.Onestudynoted that while pre-existing dental pathology was present in

two-thirds ofthecases, itwasnoticed bythe anaesthesi-ologistinonlyone-fifthofthepatientspriortointubation.6

Therefore, our questionnaire for detecting patients with poororalhealthmayserveasaguidancetothe anaesthe-siologist assessingthe risk of dentalinjury.In addition,it offersacut-offvaluefordetectingpoororalhealth.

Otherlimitationsofourstudyincludearelativelysmall samplesize37andthefactthatthedatawerecollectedfrom

asinglecentre.Despite thesmallnumberof participants, wehaveachievedagoodfittotheRaschmodel.

Itisnotclearwhichpreventivemeasures totake when apatientisconsideredatanincreasedriskofdentalinjury. The useofprotectivedevicessuchasmouthguardsis con-troversial:whilesomeauthorsarguethattheydecreasethe alreadylimited amount ofspace available,6,12 others

con-cluded that the differencein timeneeded for intubating apatientwithor withouta mouthguardwasnotclinically relevant.38 Custom-made mouthguards may be less bulky

thanothermethodssuchasusinganimpressionputty,20but

theyaremore costly andrequire timetomanufacture.If theriskofdentalinjuryisconsideredtobehigh,previous dentalassessmentisrecommended.Alternativeanaesthesia andintubationtechniquesmayalsobeconsideredwhenever possibleinsuchcases.Onegroupproposedaspecial tech-niqueforprotectingverylooseteeth,39butpreservationof

Summary

Ourgoalwastodevelopandvalidateaquestionnaireoforal healthandoralhabitssuitableforapreanaesthesiaclinic. Thisquestionnairehasdemonstratedsufficient psychomet-ric properties to be considered a reliable and valid tool formeasuringthestateoforalhealth, andalsotakesinto accountsociodemographicfactors knowntobeassociated withoralhealthandgeneralhealthstateofthepatient.

Someofthebenefitsofourquestionnairemaybe classi-fyingpatientsaccording tothedentalinjuryrisk, alerting the anaesthesiologist about complicated patients where additional precautions would be necessary during intuba-tion, informing patients with higher scores about their increasedrisk,raisingpatients’awarenessaboutthe impor-tance of good oral health, suggesting dental treatment beforesurgeryinordertopreventaninjury,anddecreasing thecompensationclaimswhichwouldresultinsavings.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Juan Carlos Llodrá-Calvo, DMD,PhD, professorof Preventive and Community DentistryattheUniversityofGranada,Granada,Spain,Dr. FernandoNájera-Sotorrio,MD,maxillofacialsurgeonatthe Quirón Hospital, Madrid,Spain, and Dr.José María Calvo-Vecino,MD,PhD,HeadoftheDepartmentofAnaesthesiology attheInfantaLeonorUniversityHospital,Madrid,Spain,who servedasscientificadvisorsonthepanelofexperts,fortheir collaborationinthisstudy.

Nofundingwasreceived.

References

1.Cook TM, Scott S, Mihai R. Litigation related to airway and respiratory complications ofanaesthesia: an analysis of claims against the NHS in England 1995---2007. Anaesthesia. 2010;65:556---63.

2.GersonC,SicotC.Dentalaccidentsinrelationtogeneral anes-thesia.Experienceofmutualmedicalinsurancegroup.AnnFr AnesthReanim.1997;16:918---21.

3.MouraoJ,NetoJ,VianaJS,etal.Aprospectivenon-randomised studytocompareoraltraumafromlaryngoscopeversus laryn-gealmaskinsertion.DentTraumatol.2011;27:127---30. 4.MouraoJ,Neto J, LuisC,et al.Dental injuryafter

conven-tionaldirectlaryngoscopy:aprospectiveobservationalstudy. Anaesthesia.2013;68:1059---65.

5.FungBK,Chan MY.Incidence oforaltissuetrauma afterthe administrationof general anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2001;39:163---7.

6.VogelJ,StubingerS,KaufmannM,etal.Dentalinjuriesresulting fromtrachealintubation-aretrospectivestudy.Dent Trauma-tol.2009;25:73---7.

7.GaiserRR, CastroAD.Thelevelofanesthesia resident train-ing does not affect the risk of dental injury. Anesth Analg. 1998;87:255---7.

8.NewlandMC,EllisSJ,PetersKR,etal.Dentalinjuryassociated withanesthesia:areportof161,687anestheticsgivenover14 years.JClinAnesth.2007;19:339---45.

9.Vallejo MC, Best MW, Phelps AL, et al. Perioperative den-tal injury at a tertiary care health system: an eight-year auditof816,690anesthetics.JHealthcRiskManag.2012;31: 25---32.

10.Warner ME, Benenfeld SM, Warner MA,et al. Perianesthetic dental injuries:frequency,outcomes,and riskfactors. Anes-thesiology.1999;90:1302---5.

11.RincónJ,MurilloR.Da˜nodentalduranteanestesiageneral.Rev ColombAnest.1996;24:1---6.

12.AdolphsN,KesslerB,vonHC,etal.Dentoalveolarinjuryrelated togeneralanaesthesia:a14yearsreviewandastatementfrom thesurgicalpointofviewbasedonaretrospectiveanalysisof thedocumentation ofa university hospital.Dent Traumatol. 2011;27:10---4.

13.Laidoowoo E, Baert O, Besnier E, et al. Dental trauma and anaesthesiology: epidemiology and insurance-related impact over4yearsinRouenteachinghospital.AnnFrAnesthReanim. 2012;31:23---8.

14.Nouette-Gaulain K, Lenfant F, Jacquet-Francillon D, et al. French clinical guidelines for prevention of perianaesthetic dental injuries: long text. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2012;31: 213---23.

15.WrightRB,ManfieldFF.Damagetoteethduringthe administra-tionofgeneralanaesthesia.AnesthAnalg.1974;53:405---8. 16.ClokieC,MetcalfI,HollandA.Dentaltraumainanaesthesia.

CanJAnaesth.1989;36:675---80.

17.YasnyJS.Perioperativedentalconsiderationsforthe anesthe-siologist.AnesthAnalg.2009;108:1564---73.

18.GattSP,AurischJ,WongK.Astandardized,uniformand uni-versaldentalchartfordocumentingstateofdentitionbefore anaesthesia.AnaesthIntensiveCare.2001;29:48---50.

19.Gaudio RM, Feltracco P, Barbieri S, et al. Traumatic dental injuries during anaesthesia: part I: clinical evaluation. Dent Traumatol.2010;26:459---65.

20.Gaudio RM, Barbieri S, Feltracco P, et al. Traumatic dental injuriesduringanaesthesia.PartII:medico-legalevaluationand liability.DentTraumatol.2011;27:40---5.

21.Folwaczny M,Hickel R.Oro-dentalinjuries duringintubation anesthesia.Anaesthesist.1998;47:707---31.

22.Rasch G. Studies in mathematical psychology: probabilistic modelsforsomeintelligenceandattainmenttest.Copenhagen: DanmarksPaedagogiskeInstitut;1960.

23.TennantA, ConaghanPG. The Raschmeasurementmodel in rheumatology:what is itand why useit?Whenshouldit be applied,andwhatshouldonelookforinaRaschpaper?Arthritis Rheum.2007;57:1358---62.

24.TennantA,PallantJF.Unidimensionalitymatters!(Ataleoftwo smiths?).RaschMeasTrans.2006;20:1048---51.

25.TennantA,PallantJF.DIFmatters:apracticalapproachtotest ifDifferentialItemFunctioningmakesadifference.RaschMeas Trans.2007;20:1082---4.

26.Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Abe K, et al. International study on the psychometric attributes of the non-motor symptoms scale in Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2009;73:1584---91.

27.McHorneyCA,TarlovAR.Individual-patientmonitoringin clini-calpractice:areavailablehealthstatussurveysadequate?Qual LifeRes.1995;4:293---307.

28.AndrichD,SheridanBE,LuoG.RUMM2030.Perth:RUMM Labo-ratoryPty;2010.

29.BortoluzziMC,TraebertJ,LastaR,etal.Toothloss,chewing abilityandqualityoflife.ContempClinDent.2012;3:393---7. 30.Pistorius J, Horn JG, Pistorius A, et al. Oral health-related

31.Guarnizo-Herre˜noCC,WattRG,PikhartH,etal.Socioeconomic inequalitiesinoralhealthindifferentEuropeanwelfarestate regimes.JEpidemiolCommunityHealth.2013;67:728---35. 32.ArmfieldJM,MejiaGC,JamiesonLM.Socioeconomicand

psy-chosocialcorrelatesoforalhealth.IntDentJ.2013;63:202---9. 33.Ando A, Ohsawa M, Yaegashi Y, et al. Factors related to toothlossamongcommunity-dwellingmiddle-agedandelderly Japanesemen.JEpidemiol.2013;23:301---6.

34.OstbergAL,BengtssonC,LissnerL,etal.Oralhealthandobesity indicators.BMCOralHealth.2012;12:50.

35.Irigoyen-Camacho ME, Sánchez-Pérez L, Molina-Frechero N, etal.Therelationshipbetweenbodymassindexandbodyfat percentageandperiodontalstatusinMexicanadolescents.Acta OdontolScand.2014;72:48---57.

36.GivolN,GershtanskyY,Halamish-ShaniT,etal.Perianesthetic dental injuries: analysis of incident reports. J Clin Anesth. 2004;16:173---6.

37.Linacre JM.Raschpower analysis: size vs. significance:infit andoutfitmean-squareandstandardizedchi-squarefitstatistic. RaschMeasTrans.2003;17:918.

38.BrosnanC,RadfordP.Theeffectofatoothguardonthedifficulty ofintubation.Anaesthesia.1997;52:1011---4.