○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ABST RAC T○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

O

ri

gi

n

a

l

A

rt

ic

le

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○IN T RIN T RIN T RO D U C T IO NIN T RIN T R○ ○ ○ O D U C T IO NO D U C T IO NO D U C T IO NO D U C T IO N○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

The interaction between the medical pro-fessional and his or her patient occurs by means of technical performance from the physician and through their personal relationship. While the first is entirely dependent on knowledge application from the doctor, increasing the ben-efits and reducing risks for this practice, the personal relationship is very complex. While participating in this momentary situation, the patient has his own social conventions, atti-tudes, expectations and needs, not necessarily exposed to the doctor, who has his or her own.1

Cognitive and clinical management skills as well as humanistic qualities and the ability to manage psychosocial aspects of illness have been indicated as important factors to be con-sidered in a study of physician performance.2

In another report, the role models for medi-cal education were investigated. T he rating “excellent” was assigned to those devoting their time to teaching and conducting clinical rounds that included consultation tasks, out-lining the importance of the doctor-patient relationship and giving attention to the psy-chosocial aspects of medicine.3

T here appears to be a growing informa-tion content in the teaching of medicine, which is continually modifying the curricu-lum of medical schools. In spite of the vari-ous curricular arrangements of different schools that are directed towards the improve-ment of technical performance, there are some humanistic qualities that may be necessary. T here is a consensus among doctors that some of these, like respect, compassion and integ-rity, are important in the physician’s training.

T hese qualities are strongly related to the doc-tor-patient interaction and can be better achieved when linked to the practice of medi-cine. When a professor attends a patient with respect and integrity, there is higher chance that the student will have the same type of behavior with his or her own patient.4

The early insertion of medical students into the practice of medicine has some advantages, such as facing up to the problems prompted by attitudes and values. In the doctor’s office there will certainly be chances for such situa-tions to arise, thus indicating an opportunity for the student to discuss the best ethical demeanor for the physician to adopt, in order to achieve the best possible result. On the other hand, it is understood that such a result will be the one that is closest to the patient’s expecta-tions, without reducing the importance of tech-nical performance or moving away from the doctor’s own ethical orientation.

It is not simple to measure the expectation that would ideally be communicated at the medical consultation. T he field observation, however, can be adapted to this purpose. The techniques of ethnography can be quite reward-ing for the acquisition and description of behaviors. During ethnographic observation four different roles can be assumed by the ob-server: 1 – complete participant, who is involved completely in the process, which may be af-fected by the observer’s actions; 2 – participant and observer, who acts but also takes notes (re-search) of his or her own subjects, whose pos-ture can be altered because their actions have been monitored; 3 – observer that participates, acting as an observer willing to intervene at any chance or invitation, which reduces the chance

• Leandro Yoshinobu Kiyohara

• Lilian Kakumu Kayano

• M arcelo Luís Teixeira Kobayashi

• M ariana Sisto Alessi

• M arina Uemori Yamamoto

• Paulo Roberto M iziara Yunes-Filho

• Rodrigo Rodrigues Pessoa

• Rosana M andelbaum

• Silvio Tanaka O kubo

• Thais W atanuki

• Joaquim Edson Vieira

The patient-physician

interactions as seen by

undergraduate medical students

General Medicine Outpatient Service, Hospital das Clínicas,

Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

CO N TEX T: The interactio n between a physician and his o r her patient is co mplex and o ccurs by means o f technical perfo rmance and thro ug h a perso nal relatio nship.

O BJECTIVE: To assess the interactio n between the medi-cal pro fessio nal and his o r her patient with the participatio n o f medical students assuming a ro le as o bservers and participants in a medical ap-po intment in an o utpatient o ffice.

DESIGN : Q uestio nnaire interview study.

SETTIN G: G eneral Medicine o utpatient o ffices, Ho spi-tal das Clínicas, Faculty o f Medicine, University o f São Paulo .

PARTICIPAN TS: Medical students perfo rmed an eth-no g raphical technique o f o bservatio n, fo llo wing 1 9 9 o utpatient medical appo intments with Clini-cal Medicine Residents.

M AIN M EASUREM EN TS: A questio nnaire filled o ut by o bserver students measured the physician’s at-titudes to wards patients, as well as patients’ ex-pectatio ns reg arding the appo intment and his o r her understanding after its co mpletio n.

RESULTS: Patients sho wed hig her enthusiasm after the appo intment (4 .4 7 ± 0 .0 6 versus 2 .6 2 ± 0 .1 0 ) (mean ± SEM), as well as so me neg ative remarks such as in relatio n to the waiting time. The time spent in the co nsultatio n was 2 4 .6 6 ± 4 .4 5 min-utes (mea n ± SEM) a nd the wa iting time wa s 1 2 3 .0 9 ± 4 .9 1 minutes. The physician’s written o rientatio n was fairly well recalled by the patient when the do cto r’s letter co uld be previo usly un-dersto o d.

CO N CLUSIO N : Patients benefit fro m physicians who keep the fo cus o n them. In additio n, this pro g ram stimulated the students fo r their acco mplishment o f the medical co urse.

KEY W O RDS: Pa tient-physic ia n intera c tio n. Pa tient sa tisfa c tio n. Tea c hing . Q uestio nna ires.

São Paulo M edical Journal - Revista Paulista de M edicina

98

of modifying behaviors; and 4 – complete ob-server, who cannot even be seen in the process that is being studied.5

Adherence by the patient to the proposed treatment and the understanding of his or her health condition can be considered as the essen-tial aspects of medical practice. Investigation of satisfaction in the doctor’s office is one of the ways that can be used to improve these aspects. Some circumstances can be pointed to as being related to the patient’s satisfaction: access to health services, outpatient service organization, treatment duration, doctor’s competence and the patient’s perception of it, clarity of information given by the doctor, doctor’s behavior and pa-tient’s expectation. On the other hand, some fac-tors do not seem to be linked to the patient’s satisfaction, such as: type of payment, patient’s clarity of communication, doctor’s personality and patient’s social and demographic character-istics or health condition.6

Some reports have shown up different as-pects of this relationship: when patients had objective consultations (physical examination and history strictly focused on the problem presented by the patient) some of them ap-peared more satisfied. On the other hand, other patients were more comfortable when part of the consultation was spent in talking about trivial matters, including a “ friendly” attitude by the doctor.7, 8

Some authors suggest there are at least three main subjects to be addressed: i) the quality of attendance, ii) the access to the doc-tor, iii) the personal relationship with him or her. When using questionnaires to investigate this field, precision in the use of words is ex-pected, so as not to give rise to contradictions. Also, the inclusion of open remarks may worsen data retrieval, but may even be essen-tial for some results. T he use of a five point scale (very poor, bad, regular, good, excellent) may be best for capturing patients’ opinions in this type of investigation.9

In this study, medical students took field observations of doctor-patient interactions during outpatient appointments. The students assumed the role of observer that participates and did a questionnaire intended to measure the doctor’s attitudes to the patient, as well as the patient’s expectations related to the ap-pointment. The adoption of this questionnaire was proposed as complementary to the prac-tice of free ethnographic annotation.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○M ET H O D S○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Students in their second semester (in their first year) from the University of São Paulo

School of Medicine were allocated to a clini-cal medicine outpatient service, the Teaching Outpatient Service (AGD) at Hospital das Clínicas (Clinical Hospital), which is a uni-versity general hospital in the city of São Paulo, Brazil. T hey were allowed to follow a Resi-dent during his or her clinical assignment, for four hours per week, with patients’ permis-sion and in the knowledge they were students, and also subject to the Resident’s willingness to receive them. We used a questionnaire with questions graded using a five point scale (very poor, bad, regular, good, excellent), some ques-tions with yes or no answers and the retrieval of demographic data. T he study protocol and questionnaire received approval from the Hospital Ethics Committee Board.

T he patients were interviewed before the medical appointment, at the documentation desk, and invited to participate in the study, allowing one student to be inside the doctor’s office. All patients were adults (45.05 years, SD 17.63), the female sex prevailed 2:1 (126 females, 65 males) and their educational level was somewhat low (2.18, SD 0.72), meaning that elementary schooling had been accom-plished. Five questions were asked of the pa-tient at this time. In the physician’s office, another student took up the role of observer and was able to take notes regarding the medi-cal consultation, including 6 items for the patient and 14 for the physician’s attitudes. Immediately after leaving the consultation office, the patient was interviewed again by a third student with three additional questions pertinent to the results of the consultation. More specifically, the student had access to a chart with the doctor’s orientation and asked the patient to repeat this to the best of their recall. T he times spent waiting for the con-sultation and in it were recorded. In order not to lengthen the time spent by the patient dur-ing the scheduled visit to the hospital, the to-tal filling-in time for the questionnaire was recorded, resulting in less than five minutes spent before the appointment and five min-utes right after it.

Statistical methods. The data collected were

analyzed using descriptive statistics, linear re-gression and the t-test, by means of a statistical software package, Sigma Stat for Windows Ver-sion 2.03 (SPSS Inc.). The inquiries about the understanding of the orientation given by the doctor, the understanding of his or her letter by the patient and the patient’s satisfaction with the appointment were considered as depend-ent variables. Data were reported as means and standard deviations, and probability levels of less than 0.05 were considered significant.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○R ESU LT S○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Doctors do not give written orientation often, regardless of whether the patient’s ap-pointment is a new one (37%) or a return visit (Table 1). Notwithstanding this, patients who were able to read these orientations also could repeat it during the recall test by students. T he patient satisfaction was higher after the con-sultation. T he total number of patients that allowed their appointments to be monitored by the students was 199. Some data were missed out, mainly regarding the time spent in the consultation (67 missing data items) and the satisfaction before the appointment (44 missing). Some patients did not comment on their educational level (58 missing).

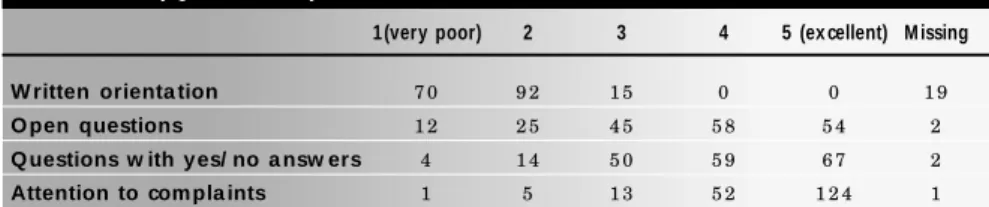

T he doctor’s orientation and letter and patient satisfaction did not show any signifi-cant correlation with all the other aspects of medical appointment. T here was no related significance as to whether the doctor gives personal attention, allows the patient to in-terpret his or her own problems, or prepares for the physical examination. T he attending Residents showed a tendency to greet the pa-tients often (75%), to ask questions requir-ing yes/no answers or open answers with the same frequency, and went straight to the pa-tients’ complaints (Table 1). T hey did not comment on the results of physical exami-nations, although when necessary they care-fully explained laboratory tests, the medicines they suggested for patients to take, and they used a vocabulary appropriate to the patients’ understanding (Table 2).

Table 1. T he attending Residents showed a strong tendency to not give written orientation to their patients, a tendency to ask questions requiring yes or no answers or open answers with

the same frequency, and went straight to patient’s complaints. 1 = very poor or rarely, 2, 3 and 4 as intermediate values, 5 = excellent or often

1 (very poor) 2 3 4 5 (ex cellent) M issing

W ritten orienta tion 7 0 9 2 1 5 0 0 1 9

O pen questions 1 2 2 5 4 5 5 8 5 4 2

Q uestions w ith y es/ no a nsw ers 4 1 4 5 0 5 9 6 7 2

Attention to com pla ints 1 5 1 3 5 2 1 2 4 1

São Paulo M edical Journal - Revista Paulista de M edicina

99

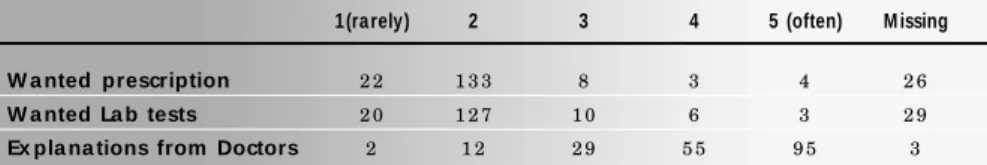

As expected, the patients did not show will-ingness in receiving prescriptions or laboratory tests, and they readily received appropriate ex-planations regarding their clinical declarations in the consultation (Table 3). Patients showed themselves to be happier right after the appoint-ment (Figure 1). Enthusiasm was different be-fore (2.62, SEM 0.10) and after (4.47, SEM 0.06) the doctor’s appointment (t-test, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, P < 0.001), although the vast majority of comments were negative in remarks made about some matters like waiting time. The time spent in the consultation was 24.66 minutes (SEM 4.45) and the waiting time was 123.09 minutes (SEM 4.91).

Patients who received a written orientation after the consultation were able to repeat it when they were able to understand the doctor’s writing (linear regression, r = 0.404, a = 1.00). There was no correlation with the patients’ educational level, although those holding graduate degrees were very few among this observed population (5%).

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ D ISC U SSIO N○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

This study has pointed out the low readi-ness among doctors to give written orientation and the difficulties in understanding it, related to the letter format. Nevertheless, the satisfac-tion was higher after the medical appointment, even with a waiting time of almost two hours. It is important to emphasize the special features of this observation made by students who were perhaps not used to clinical practice, which could be a good point. Also, this was a narrow field represented by only one period per week in one hospital, which could be a negative point.

Doctors habitually have a more negative view of the consultation than the patients, in-cluding aspects of the ability to assess patients, to offer explanations and advice on treatment and to allow them to express their feelings dur-ing the consultation process.10 T his

impres-sion can be confirmed and corroborated by the finding that physicians have a weak aware-ness of their patients’ responses, taking these as more negative than the patients themselves actually think.11 In addition, the imaginative

and experiential responses of patients to medi-cal explanations is a poorly explored area of medical study. When doctors try to detach their patients from this ability, confusion is likely and breakdowns in communication can occur.12 Finally, patient compliance increases

when the drug instructions are well under-stood, but not necessarily correlated to satis-faction with communication.13 T hese

previ-ous reports suggest that the patient-physician interactions are not only related to the satis-faction during the visit, already complex, but also to the treatment compliance, another large and complex area. Both are crucial to any successful healthcare performance.

The finding in this report that our doctors do not give written explanations can be related to the supposed low educational level of these patients, most of whom only attended elemen-tary school. However, given the previously re-ported impression of deeper negative feelings from physicians to patients, it is possible to con-sider this practice as being related to physicians’ impressions of low capacity among patients. Pa-tients comply better with the proposed therapy when they understand the doctor’s instruction.

Since doctors were uneasy about writing them down, changing this habit would allow a better chance of improving the patient compliance with their care and therapies even more. Patients who ask questions about medications are seen in a positive light, rated as more interested in their own physical status.14 However, this capacity

should not be taken for granted for all patients, and doctors who do not have such feedback may think of this as a feeling of inhibition caused by the patient’s previous experiences.

The attending physicians during this study were first-year Residents. Teaching and attend-ing patients are important aspects of creatattend-ing role models of excellency for physician profiles.3 It is

interesting to emphasize the hidden aspects of the patient-physician relationship uncovered by our new findings. Low willingness by physicians or a tendency not to greet patients should be considered as possibly resulting in a feedback of low expectations for the next or forthcoming scheduled visits. On the other hand, physicians’ careful attention to the explanation of labora-tory tests and medicines, added to an ability to seek out adequate vocabulary, are all well devel-oped techniques that help patients to become attuned to the proposed therapies.

Another aspect evoked by the students who participated was their upraised interest in the medicine course during the accomplishment of this project. The needs in medical education are not always clear, and sometimes students fall back into some idleness, as the course tack-les uninteresting subjects. Although improving students’ interest was not the intention in this project, but rather it sought to facilitate famili-arity with the scientific method and a capacity

Figure 1. Enthusiasm before (2.62 [SEM 0.10]) and after (4.47 [SEM 0.06]) the doctor’s appointment. Patients were shown to be happier right after the appointment (t-test, Mann-Whitney Rank Sum test, P < 0.001).

Table 3. Patients did not show willingness to receive prescriptions or laboratory tests, and were ready to receive appropriate explanations regarding their clinical declarations in the consultation.

1 = very poor or rarely, 2, 3 and 4 as intermediate values, 5 = excellent or often

1(ra rely) 2 3 4 5 (often) M issing

W a nted prescription 2 2 1 3 3 8 3 4 2 6

W a nted La b tests 2 0 1 2 7 1 0 6 3 2 9

Ex pla na tions from Doctors 2 1 2 2 9 5 5 9 5 3

Table 2. Residents did not comment on the results of physical examinations (P.E.), carefully explained the laboratory tests (71 situations where no laboratory tests needed), explained the medicines suggested to patients (42 situations where no medicines were prescribed) and used a

vocabulary appropriate to patients’ understanding very often. 1 = very poor or rarely, 2, 3 and 4 as intermediate values, 5 = excellent or often

1 (very poor) 2 3 4 5 (ex cellent) M issing N ot necessa ry

Com m ents upon P.E. 4 0 1 5 3 0 2 1 3 1 5 9

Ex pla ined La b Tests 9 1 4 1 9 3 2 3 4 1 7 7 1

Ex pla ined m edicines 7 1 1 2 5 4 0 6 1 1 0 4 2

Used fa ir voca bula ry 1 5 2 3 5 0 1 1 5 2

São Paulo M edical Journal - Revista Paulista de M edicina

100

for writing such reports, their interest for dif-ferent themes did improve during this experi-ence, even biochemistry and anatomy. Since this was not the scope of the investigation, and we only have the reports of ten students out of almost two hundred, we are currently testing this approach with the new 2000 class at the USP School of Medicine (FMUSP).

Giving patients the possibility of talking after the appointment made them aware of some “consumer rights” as pointed out by some. The time spent waiting for the doctor to arrive or call the patients into the office was by far the most criticized aspect. Although the outpatient schedule considers the patient to be at the hos-pital at least half an hour before the

appoint-CONTEXTO: A interação entre o médico e seu paciente em ambulatório.

OBJETIVOS: observar a interação entre o médico e seu paciente, com a participação de estudantes de Medicina assumindo papel de observadores participantes em consultório.

TIPO DE ESTUDO: Entrevista e questionário.

LOCAL: Serviço de Clínica Geral, Ambulatório Geral e Didático, Hospital das Clínicas da Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo.

PARTICIPANTES: Estudantes de medicina, no seu primeiro ano, realizaram uma técnica de observação etnográfica.

VARIÁVEIS ESTUDADAS: Durante um ano, estudantes acompanharam 199 consultas ambulatoriais com Residentes da Clínica M édica. Usaram um questionário para observar a atitude do médico para com o paciente, como também as expectativas e o

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○R ESU M O○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

entendimento desse sobre a consulta.

RESULTADOS: Pacientes demonstram estar mais animados após a consulta 4.47 (SEM 0.06) versus 2.62 (SEM 0.10) (depois x antes), apesar de algumas observações negativas como tempo de espera. O tempo de consulta foi de aproximadamente 24, 66 minutos (DP 4, 45) e o tempo de espera foi de 123, 09 minutos (DP 4, 91). A orientação por escrito, fornecida pelo médico, foi razoavelmente bem recordada quando a letra do médico podia ser entendida.

CONCLUSÕES: Pacientes se beneficiam de médicos que lhes dão atenção mais do que nos aspectos fisiopatológicos de qualquer tipo de doença. Esse programa estimulou os estudantes no curso de Medicina, e aumentou o interesse por temas áridos como anatomia e bioquímica.

PALAVRAS-CHAVES: Relação médico-paciente. Satisfação. Ensino médico. Questionários.

Ack now ledgem ents: The Residents o n duty at the Teach-ing O utpatients Service (AG D) fo r their suppo rt and atten-tio n to the patients as well as to the students, and to the Head o f the Department o f Medicine and AG D Chief, Pro f. Dr. Milto n de Arruda Martins.

Leandro Yoshinobu Kiyohara, Lilian Kakumu Kayano, M a rcelo Luís Teix eira Koba ya shi,M a ria na Sisto Alessi, M arina Uemori Yamamoto, Paulo Roberto M izia ra Yunes-Filho, Rodrigo Rodrigues Pessoa , Rosana M andelbaum, Silvio Tanaka Okubo, Thais Watanuki. Undergraduate Students, Medicine, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil.

Joa quim Edson V ieira , M D, PhD. Anesthesio lo g y Divi-sio n, Ho spital das Clínicas, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo , São Paulo , Braz il.

Sources of funding: Suppo rted by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo , São Paulo (FAPESP-nº9 8 / 0 1 9 0 -2 ) and Pro grama de N úcleo s de Excelência (PRO N EX-MCT-6 6 1 0 0 4 / 1 9 9 6 -1 ).

Conflict of interest: N o t kno wn

La st received: 2 9 Aug ust 2 0 0 0

Accepted: 0 4 September 2 0 0 0

Address for correspondence:

Jo aquim Edso n Vieira

Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo Av. Dr. Arnaldo , 4 5 5 – Sala 1 .2 1 6

Sao Paulo / SP – Brazil – CEP 0 1 2 4 6 -9 0 3 E-mail: jo aquim.vieira@ g lo bo .co m

CO PYRIG HT© 2 0 0 1 , Asso ciação Paulista de Medicina

○ ○ Pu b l i sh i n g i n f o r m a t i o n○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

1. Donabedian A. T he Quality of Medical Care. Methods for as-sessing and monitoring the quality of care for research and for quality assurance programs. Science 1978;200:856-64. 2. Ramsey PG, Wenrich MD, Carline JD, Inui T S, Larson EB,

LoGerfo JP. Use of peer ratings to evaluate physician perform-ance. JAMA 1993;269:1655-60.

3. Wright SM, Kern DE, Kolodner K, Howard DM, Brancati FL. Attributes of excellent attending-physician role models. N Eng J Med 1998;339:1986-93.

4. Boulos M. Relação médico-paciente: o ponto de vista do clínico (Doctor-patient relationship: the general practitioner’s point of view). In: Marcondes E, Gonçalves EL. Educação Médica. São

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○R EFER EN C ES○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

Paulo: Editora Sarvier; 1998.

5. Babbie ER. T he Practice of Social Research. Belmont, Califor-nia: Wadsworth Publishing Co. Inc.; 1979.

6. Lochman JE. Factors related to patients’ satisfaction with their medical care. J Community Health 1983;9:91-109. 7. Robbins JA, Bertakis KD, Helms LJ, Azari R, Callahan EJ,

Creten DA. T he influence of physician practice behaviors on patient satisfaction. Fam Med 1993;25:17-20.

8. Gross DA, Zyzanski SJ, Borawski, EA, Cebul RD, Stange KC. Patient satisfaction with time spent with their physician. J Fam Pract 1998;47:133-7.

9. White B. Measuring Patient Satisfaction: how to do it and why

to bother. Fam Pract Manag, January 1999. www.aafp.org. 10. Rashid A, Forman W, Jagger C, Mann R. Consultations in

gen-eral practice: a comparison of patients’ and doctors’ satisfac-tion. BMJ 1989;299:1015-6.

11. Hall JA, Stein TS, Roter DL, Rieser N. Inaccuracies in physi-cians’ perceptions of their patients. Med Care 1999;37:1164-8. 12. Mabeck CE, Olesen F. Metaphorically transmitted diseases. How

do patients embody medical explanations? Fam Pract 1997;14:271-8.

13. Wartman SA, Morlock LL, Malitz FE, Palm EA. Patient under-standing and satisfaction as predictors of compliance. Med Care 1983;21:886-91.

ment, the waiting time turned out to be far longer than expected, even by the Residents. We do not know what the main reason for this is, but it seems to be a deep-rooted problem for the hospital appointment books. There is already available a toll-free phone line for pa-tients to confirm their appointments and pro-gram new ones, but perhaps this toll-free number has not been properly disclosed, or provision of the service is not enough yet (busy lines), or patients have not become used to it, showing a preference for coming early. Students considered the suggestion of having an auditor or a consumer rights assistant, with the setting up of a service where patients could leave their comments. It will be necessary to take into

ac-count the costs of new position of this nature, but perhaps the satisfaction would increase and a tighter schedule would make room for even more patient assistance.

○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ C O N C LU SIO N○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○

T he use of questionnaires as ethnographic tools, putting students as observers into a phy-sician’s office, seems to be easy and accurate. T his instrument could reveal physicians’ prac-tices and their possible influence over patients’ attitudes. Patients were shown to have better compliance with doctors’ orientation when they had it written down, a practice that should be emphasized among doctors on duty.