Butt Pan Am Health Or..m 17(l), 1983

PRIMARY

HEALTH

CARE WORKERS:

THE RURAL

HEALTH

AIDE

PROGRAM

IN EL SALVADOR1

George Rubin, 2 Charles Chen,3 Yolanda

de Herrera,

Vilma de

Aparicio,s

John Massey,6 and Leo Morris’

Data from a community survey in rural El Salvador suggest that appropriately trained primary health care workers can promote contact between the health care system and the rural populations that they serve.

Introduction

In 1976 paraprofessionals called rural health aides (RHAs) trained by the Salvadorean Ministry of Health began serving rural com- munities in El Salvador. Training and field placement of these health workers continued thereafter. To evaluate some aspects of this RHA program’s health impact, we performed a sample survey of communities served by the RHAs. This article reports the results of that survey.

1 Also appearing in Spanish in the Boletin o!e la Oficina Sanitaria Pawnwicana.

2Medical Epidemiologist, Family Planning Evaluation Division, Center for Health Promotion and Education, United States Centers for Disease Control, Atlanta, Georgia.

SDemosrapher, Family Planning Evaluation Division, Center fo; Hlalth Promotion andkducation.

*Program Manager, Ministry of Health. San Salva- dor, El-Salvador. - ’

5Formerly Director of Maternal and Child Health Ser- vices, Ministry of Health, San Salvador, El Salvador; now Director of Health Planning, Ministry of Health.

CFormerly Public Health Adviser, Health and Popu- lation, Latin American Bureau, Agency for International Development, U.S. Department of State; now Health and Population Officer, U.S. Agency for International Development, Honduras.

TChief, Program Evaluation Branch, Family Planning Evaluation Division, Center for Health Promotion and Education.

Background

In recent years, increasing attention has been devoted to the use of auxiliary personnel on rural health teams in developing countries (l-3). It has been hoped that these workers could resolve many health problems in the areas they serve by providing first aid and simple treatment of uncomplicated illnesses. However, despite considerable literature on such workers’ training and use (4-S), few evaluations of their impact upon communities have been published.

Superficially, it would appear that com- munity acceptance of RHAs’ work may be related to their selection, their training and supervision, and/or the assistance they pro- vide by referring patients with complicated conditions for appropriate diagnosis and treat- ment. Some studies have suggested that cer- tain communities served by auxiliary workers promoting family planning have experienced increased contraceptive acceptance rates and decreased dropout rates among contraceptive users (9-12).

among the nations of the world in this regard. El Salvador’s principal health problems in- clude gastroenteritis, malaria, measles, and pneumonia.

In 1976 the health ministry began training paraprofessionals to provide primary health care and family planning services. These RHAs were to constitute one of the elements of the primary health care system in El Sal- vador’s rural cantons and were to be respon- sible for providing health education directed especially toward maternal and child health for rural families. It was also intended that these RHAs would promote better use of the services offered by the health centers or posts nearest the places served.

Under this ongoing program, the health ministry selects candidates for training from the communities where they will work and then trains them for 10 weeks. The RHA trainees must be literate and must come from communities with at least 100 housing units. The RHA’s activities include: (1) home visits or group meetings to discuss health topics-including cleanliness, use of latrines, care of infants, use of health center services, and family planning methods; (2) referral to health centers, especially for prenatal and postnatal care and family planning assess- ment; (3) operation of well-baby and young child clinics for infants and children up to four years of age-with emphasis on vaccination against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, mea- sles, and tuberculosis; (4) delivery of subse- quent cycles of oral contraceptives to women after initial examination at the nearest health center and provision of condoms on request; (5) provision of systematic treatment for mus- cle aches, headaches, mild diarrhea, or eye in- fections; administration of intramuscular in- jections prescribed by a medical officer at the health center; dispensing of antiparasitic medication authorized by health center per- sonnel; and performance of simple first-aid measures; and (6) promotion of registration of births and deaths.

After initial training, the RHA’s first duty

on returning to work in the community is to take a census of the village. Using these census figures, the RHA and his or her supervisor from the regional office select 100 housing units to be visited on a regular basis by the RHA. Houses with women of childbearing age and with children less than five years of age are given priority in the selection process. The RHA then visits each of these 100 houses in continual rotation, one after the other, in order to offer services and supplies and to pro- vide health center referral cards where indi- cated.

Administratively, the RHA program is an extension of the health ministry’s clinic sys- tem. Periodic supervision of the RHAs is pro- vided by health ministry staff members from the ministry’s four regional administrative of- fices and by local health center staff members. Field supervision of the RHAs is provided largely by evaluators of the Malaria Eradica- tion Program. These evaluators, experienced at field work in rural areas, are given two weeks of supervisory training and a ten-week RHA course.

Study Methods

As of March 1979, 135 RHAs had been at work in their communities for at least a year-

103 for about a year and 32 for about two years.

44 PAHO BULLETIN . vol. 17, no. I, 1983

At each household we sought to interview a female head of the household between 15 and 44 years of age. If no such person was present, we returned later that same day. If she was still not present, we interviewed any other female 15 years of age or more who was pres- ent in the household. If no eligible female respondent was present, we sought to inter- view the male head of the household.

As funds were not available for sampling and interviewing a “control” population not served by RHAs, our sample design defined two strata (as indicated above) according to the length of time the RHA had been working in each canton, and the questionnaire data were analyzed according to the length of time involved. In this regard, we first used path analysis (12) to determine the effect of the duration of RHA work on RHA and respon- dent activity. We then used multiple classifi- cation analysis (13) to examine selected indi- cators of maternal and child health care in terms of the duration of RHA work in the can- tons.

Both analyses were controlled for the dis- tance from the canton to the nearest health center and the relative size of the cantons in- volved, since these factors were thought to in- fluence RHA performance. (Among other things, average villagers in smaller cantons should have more opportunity to develop a personal relationship with the RHA than those in larger cantons.) The surveyed house- hold with the highest assigned number in each canton was taken to indicate the approximate relative size of that canton.

Regarding socioeconomic status, there is very little variation in rural El Salvador, the great majority of the population being in the lower socioeconomic stratum.

For the path analysis we used six variables, these being (1) duration of RHA work in the canton, (2) frequency of RHA visits to the respondent, (3) frequency of respondent visits to the RHA, (4) frequency of respondent visits to the health center after referral by the RHA, (5) size of the respondent’s canton, and (6) distance from the canton to the health center.

Figure 1. A path diagram showing the relationships observed between certain health-related RHA and respondent activities.

Distance between and nearest health

center

r

Responses to the second, third, and fourth variables were all assigned numerical scores giving an approximate indication of the fre- quency involved. The size of the respondent’s canton was measured in terms of the number of households in the respondent’s canton. The distance from the canton to the health center was taken to be the distance from the center of the canton to the nearest health center.

From these data we constructed a path dia- gram-a chart in which any variable shown can be affected by all the variables to the left of it (see Figure 1). In this diagram the direct or net influence of one variable on another is represented by a straight arrow. The magni- tude of this influence is indicated by a path coefficient in standard form-that is, by a beta coefficient obtained from the appropriate mul- tiple regression. The correlation coefficients of the independent variables are shown by cur- vilinear two-headed arrows. The paths start- ing at Ra, Rb, and Rc in the diagram repre- sent residual paths that include all other in- fluences on the variable in question.

For the multiple classification analysis we examined the following indicators of the level of maternal and child health care: use of a contraceptive method by female respondents

15 to 44 years of age; receipt of prenatal care by women delivering a live baby after January 1978 (subsequent to inception of the RHA program); receipt of a postpartum examina- tion by women giving birth after January 1978; occurrence of a well-baby visit for the youngest infant (under one year old) in each household; absence of diarrhea in the young- est infant of each household; and vaccination of the youngest child under five years of age in each household against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, poliomyelitis, or tubercu- losis.

Results

As Table 1 indicates, the survey included 363 respondents in cantons served by RHAs

for one year and 169 in cantons served by RHAs for two years. The table also lists the six variables used in the path analysis and shows how they were broken down.

The path coefficients displayed in Figure 1 indicate that the duration of the RHA work had a positive influence on the frequency of respondents being visited (path coefficient *ll>, suggesting strongly that respondents served by RHAs for two years were more fre- quently visited by RHAs than were respon- dents who had been served for only one year. In turn, this frequency of respondents being visited was found to have a significant positive effect on both the frequency of respondents visiting RHAs and the frequency of respon- dents visiting health centers after referral by RHAs (the path coefficients being .19 and .09, respectively), controlling for the canton’s size and the distance to the health center.

At the same time, however, canton size was found to exert a strong negative effect on the frequency of respondents visiting the RHA (the path coefficient being -.21). This suggests that people in larger cantons may have less ac- cess to RHAs than those in smaller cantons, and that larger cantons may need more than one RHA.

Similarly, relatively great distance between the canton center and the nearest health center had a positive influence on the frequency of respondents visiting RHAs and a negative in- fluence on the frequency of respondents visit- ing health centers (the path coefficients being .09 and -.12, respectively). This suggests that RHAs may be more effective in areas remote from health centers.

46 PAHO BULLETIN . vol. 17, no. I, 1983

Table 1. Survey data on six variables indicating health-related RHA and respondent activities.

Variable

Assigned numerical score

Respondents scoring

NO. %

Total number of respondents 1) Year(s) of RHA work in cantons

1 year (started in 1977) 2 years (started in 1976) 2) Frequency of RHA visits to respondents

Weekly

Once in 2 weeks Once in 1 month Once in 2 months Occasionally Never been visited

3) Frequency of respondent visits to RHA Frequent

Occasional Zero

4) Frequency of health center visits by respondents referred by RHA

Always Sometimes Never

5) Size of respondents’ cantons’

64-99 households 100-199 ” 200-299 ” 300-754 ”

6) Distance to the nearest health center from the canton center

2-4 kilometers 5-9 ” 10-14 ” 15-34 ”

(1) 363 68.2

(2) 169 31.8

(2) 197 37.0

(1) 175 32.9

(0) 160 30.1

;:; (0)

532 100.0

37 7.0

109 20.4 328 61.7

34 6.4

14 2.6

10 1.9

378 71.0 61 11.5 93 17.5 110 20.7 173 32.5 141 26.5 108 20.3

115 21.6 175 32.9 142 26.7 100 18.8 *Estimated on the basis of the total number of households surveyed in each canton.

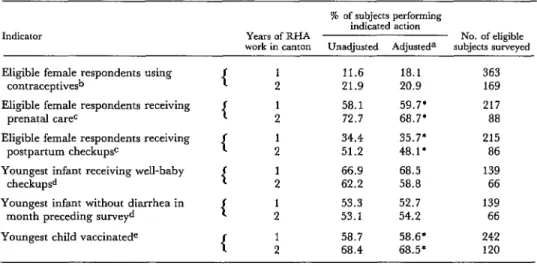

Table 2 shows the multiple classification analysis for each maternal and child health variable, by years of RHA work, both unad- justed and adjusted for canton size and dis- tance to the nearest health center. The preva- lence of contraceptive use by female respon- dents was slightly higher in the cantons served by RHAs for two years than in those served for one year, once the data are adjusted for canton size and health center distance. Five out of the six variables yielded higher values in

areas where the RHA had been working for two years. However, only three variables (prenatal care, postpartum checkups, and vac- cination) involved differences great enough to be statistically significant.

Table 2. Multiple classification analysis for maternal and child health indicators, unadjusted and adjusted for canton size and health center distance, by duration of RHA work in canton.

Indicator

% of subjects performing indicated action

Years of RHA No. of eligible work in canton Unadjusted Adjusteda subjects surveyed

Eligible female respondents using 11.6 18.1 363

contraceptivesb 21.9 20.9 169

Eligible female respondents receiving

( :

58.1 59.7’ 217

prenatal cat@ 72.7 68.7’ 88

Eligible female respondents receiving

{ :

34.4 35.7* 215

postpartum checkupse 51.2 48.1’ 86

Youngest infant receiving well-baby

1 :

66.9 68.5 139

checkupsd 62.2 58.8 66

Youngest infant without diarrhea in

( :

53.3 52.7 139

month preceding surveyd 53.1 54.2 66

Youngest child vaccinatede

{ :

58.7 58.6* 242

68.4 68.5* 120

*Difference statistically significant (piO.05).

aAdjusted for canton size and health center distance from canton center. bIn&des subjects 15-44 years of age.

CIncludes subjects 15-44 years of age who gave birth to a live baby between January 1978 and March 1979; where time of delivery was unknown, subject was excluded.

dsubjects < i year of age.

%ubjects <5 years of age; each was considered “vaccinated” if he or she had been vaccinated against diphtheria, per- tussis, tetanus, poliomyelitis, measles, or tuberculosis.

child health visits to health centers tends to decrease with increasing distance. However, if the RHAs have a greater impact in cantons more remote from health centers, and also

have a greater impact as the time served in- creases, one would expect to find that the

negative relationship between health center distance and maternal and child health indi- cators was less significant in those cantons with a longer RHA presence.

Figure 2 presents a hypothetical model in which the negative correlation between each

maternal and child health indicator and the distance to the health center is less significant in cantons where RHAs have been present for two years as compared to one.

Table 3 shows correlation coefficients ob- tained from these two groups of cantons for the six maternal and child health variables. Three variables show a statistically significant negative correlation for the group of cantons

Table 3. Correlation coefficients between maternal and child health care indicators and distance to health

center, by year(s) of RHA work in cantons.

Maternal and child health care indicator

Correlation coefficient between each indicator and the distance

to the health center with: 1 year of 2 years of RHA work RHA work Women currently using

a contraceptive method Women receiving

prenatal care Women receiving post-

partum checkups Infants receiving well-

baby checkups Infants without diarrhea

in month preceding survey

Children vaccinated

-.lOla (363)b -.040 (169) -.126a (217) -.088 ( 88) -.14ga (217) -.026 ( 88) -.042 (139) -.034 ( 66) -.045 (139) -.121 ( 66) -.064 (363) -.066 (120) aCoefficient statistically significant (pCO.05).

48 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 17, no. 1, 1983

Figure 2. A chart showing hypothetical interrelationships between the distance to the nearest health center and maternal and child health

indicators, as influenced by the duration of RHA work.

Indicators of MCH care

RESPONDENTS IN CANTONS WITH:

2 years of RHA work (r = Negative, less significant)

1 year of RHA work (r = Negative, more significant)

Near 4

Distance to ’ health ce-+- t Far

where RHAs had been present about a year. In contrast, no statistically significant nega- tive correlations were found for any variables in the cantons where the RHAs had been serv- ing for two years. These findings support the hypothesis that the longer RHA work in the cantons has tended to mitigate the negative relationship between the maternal and child health indicators and distance to the nearest health center.

Discussion

Overall, the findings show that compared to villagers of cantons served by RHAs for one

year, those in cantons served by RHAs for two years were (1) more likely to be visited by their RHA, (2) more likely to visit their RHA, (3) more likely to visit their health centers af- ter referral by their RHA, (4) more likely to receive prenatal and postpartum care, and (5) more likely to have their children vaccinated against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio- myelitis, or tuberculosis. The data also sug- gest that larger cantons need more than one

distance between the canton centers and their nearest respective health centers.

It should also be noted, however, that our study has a number of limitations. First, in the absence of a satisfactory control group, it was necessary to observe differences in RHA ac- tivities, respondent activities, and maternal and child health indicators in terms of the re- lative duration of RHA work in the commu- nity. Under these circumstances, we would not expect to see marked differences after one year; and the small sample sizes involved made it even less likely that the differences found would be statistically significant.

Second, we used indicators of contact with the health care system rather than direct indi- cators of health; and we were unable to gauge the possible effect on our results of social or economic changes that may have occurred in the study communities.

Nevertheless, our results suggest that under the circumstances prevailing in the survey

area, appropriately trained primary health care workers do promote contact between rural populations and the health care system. To the extent that this improves the health status of the population, particularly in the area of maternal and child health, we might expect to see better health indices in rural populations served by these workers than in populations without them.

The need to obtain evidence that delivery of health care services favorably alters commu- nity health indicators should be a challenge to all health workers. Our foregoing evaluation of measurable outcomes of the work of rural health aides needs confirmation using better comparison groups, larger sample sizes, and different geographic settings. Future evalua- tions should also attempt to document changes in the health status of rural populations that may be attributable to the presence, rather than merely the length of service, of health care workers.

SUMMARY

A community survey was performed to evaluate the health service impact of a rural health aide (RHA) program in El Salvador. The survey com- pared village areas (cantons) served by these para- professional aides for one year with cantons served by them for two years. The results indicate that survey subjects in the latter cantons were (1) more likely to have been visited by their RHA; (2) more likely to visit their RHA; (3) more likely to visit

their health centers after referral by their RHA; (4)

more likely to receive prenatal and postpartum care; and (5) more likely to have their children vac- cinated against diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, measles, poliomyelitis, or tuberculosis.

These findings strongly suggest that under the circumstances of this study, auxiliary health care workers can effectively promote contact between the health care system and the rural communities they serve.

REFERENCES

(1) Evans, J. R., K. L. Hall, and J. Warford. Shattuck Lecture-Health care in the developing

(3) Population Reports Services. Training non- physicians in family planning services. Population world: Problems of scarcity and choice. N Engl J Repotis Services 6:89-108, 1975.

Med305:1117-1127, 1981. (4) Swinscow, T. D. Primary care: a look at

(2) World Health Organization. Training and Kenya. Br Med J 1:1337-1338, 1977.

Utilization of Auxiliary Personnelfor Rural Health Teams (5) Smith, R. A. Medex, five years later. JAMA in Developing Countries: Report of a WHO Expert Com- 233: 135-136, 1975.

miltee. WHO Technical Report Series, No. 633. (6) Rahnema, H. E. The role of frontline health

50 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 17, no. I, 1983

(7) Fendall, N. R. E. Auxiliaries and primary medical care. Bull NY Acad Med (Second series) 48:

1291, !972.

(8) Equipe Du Projet Kasongo. Utilisation du personnel auxiliaire dans les services de Sante ru- raux: Une experience au Zaire. Bull WHO 54:625- 632, 1976.

(9) Chowdhury, S., and Z. Chowdhury. Tubec- tomy by paraprofessional surgeons in rural Bang- ladesh. Lancet 2:567-569, 1975.

(10) Editorial. Lancet 1:25, 1976.

(11) Rosenfield, A. G., C. Hemachudha, W. Asavasena, and S. Varakamin. Thailand: Family

planning activities, 1968 to 1970. Stud Fam Plann 2: 181-192, 1971.

(12) Marcoux, A. Tunisia. In W. B. Watson and R. J. Lapham (eds.). Family planning programs: World review, 1974. Stud Fam Plann 6:307-310,

1975.

(13) Duncan, 0. D. Path analysis: Sociological examples. Am J Social 72:1-16, 1966.

(14) Andrews, F. M., J. N. Morgan, J. A. Son- quist, and L. Klem. Multiple Classification Analysis (second edition). Institute for Social Research, Uni- versity of Michigan, Ann Arbor, 1973.

RUBELLA IN TRINIDAD AND TOBAGO

Between 1 January and 31 October 1982, 426 rubella cases were reported to the Na- tional Surveillance Unit of the Trinidad and Tobago Ministry of Health and Environ- ment. This figure, representing a highly significant increase over the annual average of 31 cases reported for 1979-1980, demonstrated an intense transmission of epidemic rubella virus.

An escalation in the incidence of this disease was first noted during the month of May, when some 38 cases were recorded. Peak clinical reporting was subsequently observed during September, when 110 cases were recorded.

As a result of this epidemic, health personnel are being reminded of the need to pay par- ticular attention to all newly delivered infants, and more especially to those born of mothers who have a history indicating exposure to rubella during pregnancy.

There is also an obvious need to conduct a prospective nationwide evaluation of all births in 1982 and 1983, so that infants with the congenital rubella syndrome can be iden- tified as early as possible. The data derived from such a surveillance exercise should be used to facilitate timely planning of those stratagems, programs, or activities (e.g., the ex- pansion of special educational institutions such as schools for the deaf or mentally re- tarded) that will be essential for such children.

CAREC Editorial Comment: Rubella vaccine gives a good antibody response in 95 per cent of the susceptibles vaccinated. Unfortunately, its use for those at greatest risk-the fetuses of pregnant women-is contraindicated. Immune serum globulin given after ex- posure is no substitute, since it will not prevent infection or viremia in all cases.

Therefore, the hard choice between possible congenital rubella syndrome and therapeu- tic abortion can only be avoided through prevention. Vaccine should be given regularly to susceptible women in the immediate postpartum period; to susceptible postpubertal women who are not pregnant and will avoid pregnancy for three months following vac- cination; to susceptible teachers, nurses, doctors, and other personnel likely to come into contact with rubella or with patients in prenatal clinics; and to susceptible children.