article

Care and mistreatment – two sides of the same

coin? An exploratory study of three Portuguese

care homes

Ana Paula Gil, anapgil@fcsh.unl.pt

Interdisciplinary Centre of Social Sciences (CICS.NOVA)/NOVA FCSH) Portugal

The quality of care practices is still a central issue for long-term care policy. Following seven signs used to evaluate care practices, this article presents the initial results of ongoing research carried out in three Portuguese care homes in 2017. The article uses mixed methods (24 interviews and a data survey), based on the perspectives of care workers, professional staff and managers. The findings highlight the non-recognition of care work, difficult working conditions, poor training and a limited monitoring of the care system as factors that reduce the quality of care and increase the risk of an institutionalised culture of care omission.

key words elder abuse and neglect • nursing homes • care practices evaluation • quality of care

To cite this article: Gil, A.P. (2018) ‘Care and mistreatment – two sides of the same coin? An exploratory study of three Portuguese care homes’, International Journal of Care and Caring, 2(4):

551–73, DOI: 10.1332/239788218X15411703595128

Introduction

Public investment in a long-term care system and promoting a mechanism to control quality in institutional care, ensuring compliance with care standards, is a way of protecting residents from elder abuse, and a central issue for long-term care policy. However, even where an official quality-control system is in place to ensure that all services meet minimum standards, poor quality and the mistreatment of older people can be found in long-term care services (EC, 2010).

The organisational factors affecting the quality of institutional care have been identified, and include: the physical care environment; institutional rules, regulations, policies and staffing; practices (use of restraints and inadequate care plans, records or supervision); resident-related factors (poor communication, limited opportunities for meaningful engagement and lack of dignity and respect for residents) (Lafferty et al, 2015); and macro-structural factors (changes in ownership, financial pressures or ineffective external agency monitoring) (Hyde et al, 2014).

Winner, IJCC & Transforming Care conference 2017

Best Paper award

Despite recognition of the need for further research on the interactions between organisations, staff and residents (Castle et al, 2015; Kamavarapu et al, 2017), there is still uncertainty about these and how they affect care practices. Tronto (2010) states that ‘if we are committed to policies to improve care we need to answer the question: how can we tell which institutions provide good care?’ or, in contrast, bad care. She defined bad care as the lack of adequate accounts of power, purpose and plurality, and highlighted how conflict, power relations, inconsistencies and competing purposes and divergent ideas about good care could affect care processes. She proposed seven signs to evaluate care practices that are conducive to providing bad care: (1) a resident is conceived as someone who needs protection due to their dependency and vulnerability; (2) needs are taken as given within the organisation and are not person-centred; (3) care is considered a commodity, not a process – the usual view that arises from thinking of care as a commodity is to see any increase in caring as a reduction in time for another activity; (4) care receivers are excluded from making judgements because they lack expertise due to their dependence; (5) care is narrowed to caregiving, rather than a process that includes attentiveness and responsibility; (6) care workers see organisational requirements as hindrances to, rather than support for, care; and (7) care work is socially devalued and therefore less rewarded and attractive, with people suffering from discrimination in the labour market more easily becoming care workers (women, the less qualified, the long-term unemployed and immigrants) (Tronto, 2010: 163–6).

Following these signs, and through three case studies in one council in the metropolitan area of Lisbon, Portugal, this article aims to explore how institutional scenarios devaluing care work affect care practices, leading to the institutionalisation of a care omission culture. The lack of recognition of care work, poor wages and difficult working conditions are explained by the low value that society gives to care for older people (Hussein, 2017) and inadequate care, which may also be a reflection of low public investment in the care system.

Care versus ‘neglectful’ care – an issue for social policy

Institutional care includes the provision of health and social care to respond to the increased need for long-term care, and quality care is defined as effective care accessed according to need. The focus on service quality is guided by Donabedian’s (1980) approach and encompasses the structural features of the settings, service delivery process and outcomes. This approach has been criticised, however, for focusing too much on clinical quality and devoting little attention to residents’ quality of life (OECD, 2013; Schulmann et al, 2016).

Some authors have proposed linking quality of care and quality of life (Noelker and Harel, 2001), and distinguishing between quality care and the quality of caring, which implies recognising both the nature of care activities and the nature of staff and resident interactions. In these conceptualisations, care is associated with a generalised consensus on social cohesion, minimising the diversity of experiences and the existence of conflicts among those who provide and who receive care in a process of reciprocity. Caring for someone over a long period without support is known to affect carers’ health, financial status and social integration (Rodrigues et al, 2012; Yeandle, 2016; Yeandle et al, 2017). These impacts also extend to care work. Hussein (2018) highlights care workers’ vulnerability to highly stressful job experiences and the risks to their

health and well-being. Adequate working conditions, quality supervision, social support and social recognition are measures important for safeguarding workers’ well-being and ensuring the quality of care delivery (Hussein, 2018). Training, working conditions and contextual factors, structures and processes are all factors that affect the quality of long-term care outcomes (Schulmann et al, 2016).

Despite a large body of work on care, care and caring remains ‘rather hidden, almost secretive, terrain’ (Yeandle et al, 2017: 8); some conceptualise this as an ambivalence process (Connidis and McMullin, 2002). A duality associated with the care concept is highlighted by Kelly (2017: 98): ‘care and violence cannot be separated. Care includes violence; violence is a part of care’. For her, violence is an integral part of the care process, with both concepts part of a continuum in institutional care, with care conceived of as an integral and holistic process. Concerning care and mistreatment in this continuum in institutional care, there is an intermediate concept, inadequate care. Malmedal et al (2014) claim that inadequate care links care quality and elder abuse. ‘Inadequate care’ may lead to a loss of dignity, making individuals more vulnerable to abuse and neglect. It is an all-inclusive term, defined as a set of actions or omissions that may affect the physical and psychological well-being of residents and their quality of life. This leads to a third concept, neglectful care: the failure to provide care when needed, or providing inadequate assistance (Dixon et al, 2009).

Hawes (2003) defined two types of neglect. The first is represented by failure to provide needed assistance; the second occurs when a care worker performs a task for which he or she is not qualified without supervision. The distinction between active and passive neglect is needed because the former involves intentionality to cause harm, while the latter relates to organisational aspects of long-term care policies. Pressures to reduce public expenditure on care have been accompanied by a deterioration in care workers’ wages, working conditions and professional standing (Yeandle et al, 2017).

This article starts with an overview of long-term care provision in Portugal. It then presents results from three case studies of individuals (managers, professional staff and care workers), using mixed methods, in-depth interviews and observations of daily life practices. Based on a phenomenological perspective (Schutz, 1998), the aim is to analyse the importance that social actors in a particular organisational system give to care practices and the associated quality care factors. Thus, grasping the meanings of managers’ and care workers’ subjective experience is a means of analysing how social reality is perceived. This theoretical framework also allows us to understand the ways of thinking about, and the subsequent interpretations of, the daily reality of care practices in nursing homes, as well as to explore consensuses and paradoxes in care practices, thus giving visibility to the ‘underground’ world of care.

The long-term care context in Portugal

Portugal has mixed long-term care, composed of a network of services, including care centres, home-based services and nursing homes (‘residential structures for older people’). Since the 1990s, the Portuguese government has invested in care services for older people through parallel programmes set up to develop an integrated network of services: ‘Pares’, a programme for widening the network of social facilities, and the National Network for Integrated Continuous Care (Ferreira, 2010).

In the early 1980s, only 2% of people aged 65+ in Portugal had places in nursing homes. By 2011, 70% of people living in collective social support dwellings (4% of

the 65+ age group) were women aged over 80 with severe care needs (including cognitive and physical impairments) (Gil, 2010). Between 2000 and 2015, the number of nursing homes increased by 65% (from 1,469 to 2,418) and the number of residents by 69% (from 55,523 to 94,067) (GEP, 2017).

Nursing homes offer support through collective accommodation, meals, health care and leisure activities. These services and facilities for older people are mainly provided by (partly state-funded) non-profit institutions. Registration and inspection take place at a national level through social security services, based on national standards. Profit and non-profit institutions must have a licence provided by the Social Security Institute and meet relevant legal requirements, which define organisational, operational and installation conditions (Ordinance no. 67/2012). Under Article 8, a residential facility must provide specified services 24 hours a day (covering nutrition, personal care, laundry, cleanliness, recreational activities, support with everyday activities, nursing and health care, and the administration of medicines), with a technical director and specified ratios of residents to staff (care assistants, nurses, domestic service managers, ancillary/social activities workers, etc).

Legal requirements concerning structural and technical standards are supervised by the Social Security Institute through an annual (and usually ‘announced’) visit by local social services and social security inspection services. In the event of a complaint, inspections are ‘unannounced’. Irregularities detected trigger either administrative and urgent closure (due to a high risk to residents from poor-quality care) plus urgent criminal proceedings to establish any evidence of mistreatment, or designation as ‘irregular’ due to non-compliance with mandatory legislated elements.

Since 2014, irregularities may also give rise to simple processes and punitive fines (‘very serious’, ‘serious’ or ‘minor’, under Decree no. 33/2014). Intended to improve service quality, these do not guarantee quality; the sanctioning framework is more beneficial for the non-profit sector. Institutional care assessment is mainly socially oriented, with the state’s role limited to funding and licensing services (Lopes, 2017), which is largely a consequence of the decision to privatise public services and relinquish the state’s regulatory role (Ferreira, 2010).

Public investment in long-term care in Portugal is very low (0.5% of gross domestic product [GDP], compared with Netherlands (3.7%), where public expenditure on long-term care was around double the OECD average (1.7%) (OECD, 2017: 217). Portugal has the lowest percentage in Europe of formal long-term care (LTC) workers per 100 persons aged 65+ (a coverage gap of 90% due to insufficient LTC workers; see Scheil-Adlung, 2015: 81), and the lowest concentration of care workers, ‘less than 1 worker per 100 people aged over 65’, compared to Norway’s 12.8 or Sweden’s 12.4 per 100 (OECD, 2016: 18).

Most formal LTC workers in institutions are personal carers (70%); 30% are nurses (OECD, 2016) and much institutional care is provided by care workers with no training (OECD, 2013). There have been some state efforts to ensure that care workers receive training and have necessary skills, with a new ‘care assistant’ category needing nine years of schooling, three years’ work experience and six months’ vocational training created (Article 5, Decree no. 414/99). Despite a 1990s’ regulation, in practice, there is no public control of care work, with an increasingly precarious care workforce, poor wages (€607 per month1) and difficult working conditions. This

care worker in institutions’ being one of the main occupations to which long-term unemployed women are directed (EIGE, 2017; Eurofound, 2017).

Methods

Sampling and procedures

The article presents initial results of an ongoing research study, ‘Ageing in an institution: an interactionist perspective on care’,2 in a council within the Metropolitan Area

of Lisbon. Forty nursing homes (profit and non-profit) were invited to participate.3

In an exploratory phase in 2017, research instruments were tested with managers, professional staff, care workers and residents in three non-profit nursing homes (A, B and C, with 84, 61 and 40 residents, respectively) providing care to physically and mentally dependent people (80% of residents have dementia).

Participants

With informed consent guaranteeing confidentiality, anonymity and permission to record, 24 individuals were interviewed. All interviews (lasting 30–90 minutes) were subsequently transcribed. Participants were given identifiers (E1 to E24) for each institution A, B and C. Most were women in full-time work; a few (n = 8) declined to give their age.

We conducted in-depth interviews with nursing home managers to obtain data on organisational features of the settings, focused on: the organisational definition of care; quality-control mechanisms; and problems associated with care work and quality aspirations.

Nursing home

Care home characteristics Fieldwork

A Rural parish

84 residents

Services: social care, health care (medical, nurse and rehabilitation), leisure activities

Person care (36 care workers)

Interviews: 1 manager 3 professional staff 4 care workers 11 residents Survey: 36 questionnaires Fieldwork: 10 days B Rural parish 61 residents

Services: social care, health care (medical, nurse and rehabilitation, psychology support), leisure activities Person care (26 care workers)

Interviews: 1 manager 3 professional staff 7 care workers 13 residents Survey: 26 questionnaires Fieldwork: 10 days C Urban parish 40 residents

Services: social care, health care (medical, nurse), leisure activities

Person care (14 care worker)

Interviews: 1 manager 1 animator 3 care workers 6 residents Survey: 14 questionnaires Fieldwork: 5 days

Of the 14 care workers interviewed, only two had training prior to admission; all worked full time. The in-depth interviews focused on their caregiving experience and the main problems that they faced in care work. During the interviews, we felt that care workers were afraid to talk and of losing their jobs. To safeguard their identities, we decided (after the interviews) to introduce a self-administered questionnaire, which could be analysed anonymously without naming institutions. We distributed 76 questionnaires and obtained 41 responses (54%): 92% were women (mean age 43, age range 22–67) with low qualifications (less than five years’ education). These produced a social portrait of care workers’ working conditions (hours, salary, contract type, training, social benefits, etc), work environment, personal impacts (burnout levels, physical and mental health), organisational conflicts and social attitudes towards ageing and care.

Additionally, 30 in-depth resident interviews were conducted, focusing on: the admission process; daily life experiences; and social perceptions of the quality of life, Table 2: Description of participants by gender, age and function

Interviews

Nursing home Code Sex Age Function Work regime

A E1 F 42 Manager Full time

A E2 F 34 Social worker Full time

A E3 F 32 Rehabilitation staff Full time

A E4 F 36 Animator Full time

A E5 F 24 Care worker Full time

A E6 M 29 Care worker Full time

A E7 F * Care worker Full time

A E8 F * Care worker Full time

B E9 F 48 Manager Full time

B E10 F 40 Social worker Full time

B E11 F 34 Animator Full time

B E12 F 36 Psychologist Part time

B E13 F 64 Care worker Full time

B E14 F 38 Care worker Full time

B E15 F 59 Care worker Full time

B E16 F 50 Care worker Full time

B E17 F * Care worker Full time

B E18 F * Care worker Full time

B E19 F * Care worker Full time

C E20 F 48 Manager Full time

C E21 F 29 Animator Full time

C E22 F * Care worker Full time

C E23 F * Care worker Full time

C E24 F * Care worker Full time

capturing information about items such as cleanliness and comfort, good nutrition, safety, control over daily life, social interaction, occupation, accommodation, and dignity. The fieldwork took between one and two weeks in each nursing home, forming a total of 175 hours of observations (seven hours per day). Observation records sought to capture information on accommodation, cleanliness and comfort, nutrition, safety, occupation and social interaction, and residents’ appearance. However, in this article, the focus is mainly on the perspectives of care workers, professional staff and managers.

Data analysis

The interviewee material was transcribed and analysed in detail using thematic content analysis. The transcription and English translation of the quotations is intended to preserve the original form of the oral language used by participants to share their experiences. A three-stage thematic content analysis was employed: (1) coding, the process of assigning categories and subcategories reflecting previously defined themes as well as new ones (such as organisational conflicts); (2) storage, the compilation of all excerpts from the text subordinate to the same category in order to permit comparison (see Table 3); and (3) interpretation, through an analytical induction method (Patton, 2002).

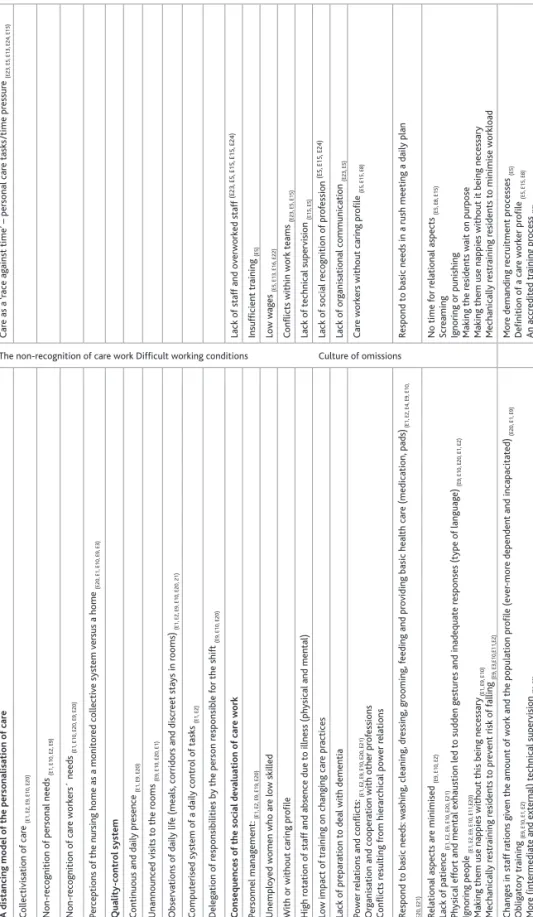

The objective and analytic framework focused on discursive meaning: the perception and experiences of care workers, professional staff and managers about caring and care work in a nursing home. To explore the intersection between meanings of care practices, associated quality care factors and the main problems emerging in care work and quality aspirations, the analysis focused on these aspects and how they are portrayed in manager and professional staff narratives. Analysis was based on four themes: a distancing model of personalisation of care; a quality-control system; the consequences of the social devaluation of care work, including (in)adequate care; and quality aspirations. The analysis of care-worker interviews highlighted their difficult working conditions, the non-recognition of the profession and indicators of (in)adequate care. Analysis was based on four themes: (1) a distancing model of personalisation of care; (2) a quality-control system;(3) the consequences of the social devaluation of care work, including (in)adequate care; and (4) quality aspirations.

Descriptive analysis of the questionnaire was made using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (version 25), with NVivo 11 for windows (quality data analysis computer software package) – used in some of the content analysis.

Seven signs to evaluate care practices: managers’ and care workers’

perspectives

Quotations in this section are taken from the interviews and raise themes related to the collectivisation of care and non-recognition of personal needs. The first warning sign of institutional care is related to how the care model responds to residents’ needs, a person-centred care emphasising the individual’s autonomy (Nolan, 2004) and care workers’ needs (Tronto, 2010).

Table 3:

Descr

iption o

f emer

gent themes anal

ysed thr ough intervie ws Themes Manag er s and pr of essional staf f per spectiv es Car e w ork er s’ per spectiv es Or ganisational definition o f car e A distancing model o f the per sonalisation o f car e

The non-recognition of care work Difficult working conditions Culture of omissions

Car e as a ‘race ag ainst time’ – per sonal car e tasks /time pr essur e (E23, E5, E13, E24, E15) C ollectivisation o f car e (E1, E2, E9, E10, E20) Non-r eco gnition o f per sonal needs (E1, E10, E2, E9) Non-r eco gnition o f car e worker s´ needs (E1, E10, E20, E9, E20) Per ceptions o f the n ur

sing home as a monitor

ed collectiv e system v er sus a home (E20, E1, E10, E9, E3) Quality-contr ol system C ontin

uous and dail

y pr

esence

(E1,

E9,

E20)

Unannounced visits to the r

ooms (E9, E10, E20, E1) Observ ations o f dail y lif e (meals, corr idor s and discr eet sta ys in r ooms) (E1, E2, E9, E10, E20, 21) C omputer ised system o f a dail y contr ol o f tasks (E1, E2) Deleg ation o f r esponsibilities b y the per son r esponsible f or the shift (E9, E10, E20) Emer gen t pr obl ems in car e w ork C onsequences o f the s ocial de valuation o f car e w ork Lac k o f staf f and ov erworked staf f (E23, E5, E15, E15, E24) Per sonnel manag ement : (E1, E2, E9, E19, E20) Insufficient tr aining (E5) Unemplo yed women w ho ar e low skilled Low w ag es (E5, E13, E16, E22) W

ith or without car

ing pr

ofile

C

onflicts within work teams

(E23, E5, E15) High r otation o f staf

f and absence due to illness (

ph

ysical and mental)

Lac k o f tec hnical supervision (E15, E5) Low impact o f tr aining on c hang ing car e pr actices Lac k o f s ocial r eco gnition o f pr of ession (E5, E15, E24) Lac k o f pr epar

ation to deal with dementia

Lac k o f or ganisational comm unication (E23, E5) Power r

elations and conflicts:

(E1, E2, E9, E10, E20, E21) Or

ganisation and cooper

ation with other pr

of essions C onflicts r esul ting fr om hier ar chical power r elations Car e worker s without car ing pr ofile (E5, E15, E8) (In )a deq uat e car e

Respond to basic needs:

w ashing , cleaning , dr essing , gr ooming , f eeding and pr

oviding basic heal

th car e (medication, pads) (E1, E2, E4, E9, E10, E20, E21)

Respond to basic needs in a r

ush meeting a dail

y plan Relational aspects ar e minimised (E9, E10, E2) Lac k o f patience (E1, E2, E9, E10, E20, E21) Ph ysical ef for

t and mental exhaustion led to sudden g

estur es and inadequate r esponses (type o f languag e) (E9, E10, E20, E1, E2) Ignor ing people (E1, E2, E9, E10, E11,E20)

Making them use nappies without this being necessary

(E1, E9, E10) Mec hanicall y r estr aining r esidents to pr ev ent r isk o f f alling (E9, E3,E10,E11,E2) No time f or r elational aspects (E5, E8, E15) Scr eaming Ignor ing or punishing Making the r esidents w ait on pur pose

Making them use nappies without it being necessary Mec

hanicall y r estr aining r esidents to minimise workload Quality aspir ations Chang es in staf f r ations g iv en the amount o

f work and the population pr

ofile (ev

er

-mor

e dependent and incapacitated

) (E20, E1, E9) Oblig atory tr aining (E9, E10, E1, E2) Mor

e (intermediate and external) tec

hnical supervision

(E9,

E2)

Social secur

ity assessment model mor

e per

son- and well-being-centr

ed (E1, E2, E9, E10, E20) Mor e demanding r ecr uitment pr ocesses (E5) Definition o f a car e worker pr ofile (E5, E15, E8) An ac cr edited tr aining pr ocess (E5)

Better working conditions – high w

ag es (E5, E13, E16, E22) Lov e f or the pr of ession (E8, E5)

A distancing model of the personalisation of care

A dominant conception emerges from the manager and professional staff interviews regarding care provided in a nursing home. This follows a collective structure that fulfils a set of assumptions, where standardised routines and the care provided are generic and the objective is to respond to basic needs: hygiene, nutrition and comfort. As E2 (social worker) states: “Residential structures are planned in practice to respond to feeding, hygiene, comfort and little more”.

E1 (manager) explains:

“Individualisation of care! There’s none! And there should be. 100% there is none! Not only due to the difficulty to balance times for residents and care workers’ times, but also the fulfilment of the tasks…. The basic care is there! The hygiene is done, the skin treatment is done, diapers are changed several times a day … but, in fact, “I want to stay in bed until noon!” the resident cannot stay. It is not only one who will not want to stay, and this has to do with the rules of the house…. It is very difficult to balance the rules dictated by the institution and the preservation of autonomy.”

E9 (manager) believes the model is centred on a task: “It is a task with a schedule to be fulfilled” in a “race against time”, in which relational aspects are minimised and of secondary importance given that the most important thing is to respond to basic needs: washing, cleaning, dressing, grooming, feeding and providing basic health care (medication, pads, etc).

Sometimes, entering a nursing home means the loss of identity, individual freedom and life habits (consumption of alcohol, tobacco, food) incompatible with institutional rules. E10 (social worker) lists a set of questions posed by residents:

“All my life, I’ve drunk a glass of wine with my meals, all my life! It was just a glass of wine and now I can’t? But why can’t I now? Because others cannot because of their medication? But my medication does not interfere with anything; the doctor told me it does not interfere with anything. So, what’s different? I have COPD (Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease), I have severe respiratory problems, but, damn it, I want to keep on smoking! And they count my cigarettes? Why can’t I eat what I used to? Why do I have to be at a table where I eat a diet dish and behind me there is someone eating a more appealing dish? Why do I have to be in a room with that gentleman who is drooling, making noise, why? I left my purse here; I don’t take anyone’s things, why do they take my things? I decided that these clothes are still good for tomorrow and why are they already going to be washed? Why do they do this without consulting me?”

The non-recognition of the older person as a client or customer means a subculture that perceives care not as a service being paid for, but as provided to a stereotypical vision of a devalued and excluded social group: “The other [resident] is very lucky to be here, sometimes I think that’s what they think, the old people are lucky to be here, because they have everything here – what are they complaining about?” (E2, social worker).

The labelling of residents (as little pests, bedridden) organises care practices and distributes human resources according to the ability to care. A system that looks at residents as incompetent because they are dependent, in which there is no space to listen to the voice of the individuals cared for, and in which any suggestions about care are deemed to be resistance or obstruction is a sign to assess the quality of good care (Tronto, 2010: 165).

E20 (manager) believes that there is a tendency to ‘box in’ the care home, not like a home, but as a closed place full of restrictions and hazards. A balance between collective rules and individual tastes and interests will help the resident feel that the space is theirs:

“If we want to impose many rules and many formalities in the institution, perhaps the person will not feel well.… For example, it is not mandatory to always have to get out of bed at 07.00 in the morning. Obviously, it is good for everyone to get out of bed, but if you can stay in bed until 07.30 or 08.00, why should we not do it if we can? I think we make the care home too ‘restrictive’ and, in the end, it is the residents’ home, so there will always be risks. I cannot, nor can anyone, have a care assistant for each one or two residents and I think people try to make care homes very strict. A resident is diabetic so they cannot eat half a bowl of rice pudding because they are diabetic. I believe this makes nursing homes too strict, that is, people end up being so trapped that they don’t feel good and don’t feel at home.” (E20, manager)

Nursing homes – places full of prohibitions

“To no longer have the power of decision” is regarded by E2 (social worker) as a form of social exclusion. E2 (social worker) reports three situations in which the person is stripped of his or her ability to decide how and where to live. First, under Portuguese legislation, the contract for the service provided must be signed by the institution and the resident. In rare situations, this contract is carried out by the older person with the family as mediator of the admission process. One of the reasons is because entrance is made without their own consent, sometimes due to their physical and mental vulnerability.

Second, the person is not allowed to manage his or her own income and is discouraged from having personal effects as these are considered as at risk of being stolen. A third risk is the risk of falling, with the institutional space becoming a place full of prohibitions about physical hazards.

Although all the managers and professional staff recognised the harm to the physical and psychological well-being of residents of using restraints in the institutional space, it is an example that illustrates how the institutional dimension dominates (eg someone is permanently present and vigilant in the meeting rooms), to the detriment of the individual dimension. In all the nursing homes, local outings are encouraged, with prior notice to the institution by residents themselves (or their families in cases of people in early stages of dementia), but this is controlled (doors closed, exits controlled by an electronic gate).

E1 (manager) reports episodes of attempts to escape, mainly among people with dementia, and the need for security systems. People can stroll in the landscaped spaces

around the home but with ‘electronic bracelets’ that indicate when they approach the main gate. This is a practice specifically for people with dementia as it is not policy to contain residents: “It is the reason why we don’t tie people down, they walk around” (E1, manager), especially in summer. Observation records contradict this position, however, as some people were immobilised for hours with bands, belts and bed sheets (in the mornings and afternoons). This practice is generally accepted and was normalised in all the nursing homes we observed, without supervision by health professionals or staff.

E2 (social worker) justifies this practice as at the request of families to prevent falls. She claimed that containment was a necessary safety measure to prevent falls, which are greater when the resident uses a wheelchair. She recounts several cases of the ‘mandatory’ use of containment: people who have lost their ability to sit vertically; and persons with dementia who are at risk of falling when they stand up. There is caution in the terminology used, however: “It’s not tying up, but containment” (E20, manager); and “we used safety belts, bands and no sheets” (E3, rehabilitation staff). However, in the interview data, use of other forms of restraint, such as sheets and belts, are mentioned and this was confirmed by observation of daily practices. All interviewees felt that containment was not a form of physical abuse:

“I am not going to say I am for or against immobilisation – but, then again, it is a question of security, of prevention, now they should do these trips, these walks, sometimes even just from the room to the cafeteria, why not?… It’s 3 or 4 minutes to walk a little bit, and then they can rest for a bit, but the person walked a little bit. And that, yes, that is careless, this could be done … sometimes, it is lack of time; other times, it is lack of time and a lack of willingness.” (E10, social worker)

Quality-control system

The daily and attentive presence of managers depends on the organisational model. In nursing home A, the manager’s role involves financial and human resources management, with day-to-day operations delegated to a social worker and welfare officer. Nursing homes B and C, by contrast, have a ‘person responsible for the shift’, including weekends, on a rotation; this informal figure performs the same tasks but also has a care oversight role.

All the managers pointed out that there are different strategies for assessing personal care. Unannounced visits to residents’ rooms, and discreet stays in the rooms, are used to observe and witness behaviours and interactions between residents and care workers – “It is more appeasing, we walk around” (E10, social worker) – or to observe mealtimes (E9 and E10). E1 (manager) reports her observation strategies in which behaviours compromising the person’s individuality and autonomy lead to dependence (unnecessary use of incontinence pads):

“Sometimes, I like to go into the living room without anyone knowing, and to sit next to them just watching and, sometimes, not even the care workers realise I’m sitting there among them. I do this on purpose and I hear a lot of things, I see a lot of things, and I’m not saying that it’s done with malice, on purpose, but, for example, the residents ask: ‘I want to go

to the bathroom’, we have at the moment three bathrooms … ‘Mr X, do you want to go to the bathroom? It’s occupied, you have to wait a little, but use the incontinence pad, it’s easier’!… When the resident asks, ‘I don’t know where I put my wallet, I think I left it in the room’, and maybe we are talking about a person who is already in a process of dementia, ‘No, it’s not’. ‘NO’ is always the first thing people are told and, therefore, we are not going to meet the needs of the resident 100%.” (E1, manager)

Institution A implemented a computerised system of a daily control of tasks. In addition to the indirect control of care delivery, this allows for individualised needs and appropriate care (eg incontinence pads, protective underwear, medication, specialised care).

For E9 and E20 (managers), an attentive and continuous presence in the institutional dynamics is a strategic element regulating interactions between residents and care workers. Participants were asked how they deal with situations of inadequate care. E9 (manager) recognises the most problematic as abrupt language (“the terminology used”) or ignoring the person (“a person is asking something and is completely ignored”). There is no verbal contact or any kind of empathy. The care worker does not explain “what is being done. She arrives there, and it’s a form of aggression; they want that person to cooperate” (E10, manager), or there is not even a good-mannered compliment: “[they] start taking care of the person without even saying good-day or goodnight” (E10, manager). Physical efforts and mental exhaustion sometimes lead to sudden gestures and inadequate responses towards an older person: “We have witnessed a lack of patience with the elderly. There is no patience to wait and to listen, they don’t have the patience.… It isn’t easy to change nappies, pees, poos; it’s not easy” (E1, manager).

E2 (social worker) identifies another problem: “80% of people living in care homes today have dementia”. Institutions are not ready to deal with dementia, however:

“a person suffering from dementia at the physical level does not need more than we have to offer, but we’re not ready to deal with these cases because, at the human level, we’re not prepared for this, and, to me, the institutions are the human level, don’t you agree?” (E2, social worker)

How do managers deal with situations of inadequate care? They immediately criticise them, and when more stringent measures are called for, staff are dismissed. This must be minimised, however, due to the shortage of human resources. To avoid dismissing staff, more conciliatory measures are sought, such as talking, calming down tensions and managing conflicts.

Consequences of the social devaluation of care work

E20 (manager) emphasises personnel management, considering it central to institutional dynamics. It is a negative element that exhausts those who run these organisations that rely on a socially devalued and underpaid profession. Managers and professional staff agree that care work is “the last resort people seek” (E1, manager) by low-skilled, unemployed women, sometimes with no experience of caring. Very demanding recruitment processes are incompatible with the limited offer that exists

in the labour market and the requirements of the profession: “There is always a small number of people, but we don’t have the luxury to choose” (E9, manager). The worst problem is finding applicants with relational skills who can take care of someone. Nevertheless, long-term unemployed women are sometimes “extraordinary” (E9, manager) in terms of their “sensitivity” (E20, manager) and “nature” (E1, manager):

“The biggest difficulty is finding someone who likes working, who is trustworthy and who likes, someone who likes the profession. That’s what I think is the most difficult because, it’s what I usually say, the pay isn’t very high, but there needs to be love for the job as well as the love of giving and sharing…. It isn’t a job, it’s work, and it’s a lot of work, it’s physical work and psychological work!” (E20, manager)

The problem of turnover, unjustified absence, shifts (especially at night), physical and mental illness, and the consequences of years of care work are some of the problems that cut across the three nursing homes: depression, tendonitis and back pain, essentially due to weight and, often, bad lifting positions. There is a mandatory annual medical examination in order to comply with health, hygiene and safety at work legislation. This involves a generic exam (electrocardiogram, hearing, blood analysis), but mental health is totally neglected (“mental assessment doesn’t exist” (E20, manager).

Although training is not mandatory when staff take up post, all the nursing homes implemented a system of practical training, provided by older care workers previously selected or conducted by nursing professionals. The training comprises three days of training ‘following’ a senior care worker and a few days (three, five or 10, depending on the nursing home) for observation. Institution B organises systematic ‘thematic meetings’, moderated by psychologists, in which staff discuss themes such as dementia care and basic care. As the workers have a very low educational level, they have difficulty understanding the content of the training (E12, psychologist). In institution A, training is mandatory. E1 (manager) is sceptical about training: care workers don’t “like to learn”; issues such as ethics, confidentiality and conflict management are priority training areas.

Tronto (2010) considers this attitude of blaming lower-skilled care workers who may have inadequate resources and are subject to greater pressure as another sign that an institution has little capacity to provide good care. Marginal groups in society (women, long-term unemployed people, immigrants) who face discrimination in the workforce tend to become care workers, reflecting the secondary status of care in society and the social devaluation of care work. In this perspective, the allocation of responsibilities between those who manage and those who execute personal care tasks gives rise to conflict, power relations and divergent ideas about good care.

Power relations and conflict: the invisibility of informal relations

Sometimes, orders given by the manager are not accepted by care workers, mainly older ones, leading to conflict within care teams. This is related to the type of leadership; informal leadership often emerges within care worker teams, discouraging extra activities or innovative care practices. When staff block new norms and practices dictated by managers or professional staff, or, indeed, anything that is institutionally

instituted, invisible figures and powers hidden within the teams of care workers emerge:

“There are those who have a certain power here, a strange thing. It is an informal, invisible power.… The manager suggests ‘Let’s start doing this’, and writes it down and begins to realise it is not being done – and after she sees who was there and receives comments, ‘On my shift, it’s not done that way’.” (E10, social worker)

The most difficult problem is the informal power struggle, which is worse when care workers with years of care work and experience, unwilling to change practices and institutional routines, are involved. E2 (social worker) and E21 (animator) share this perspective. The worst problem is to manage care workers and adapt procedures and practices: “Now, they come and tell me ‘How am I supposed to do my work?’. But I know how to do my work properly and correctly. I know!” (E2, social worker).

Non-acceptance of organisational changes leads to undeclared conflicts within the organisational space that constitute real forces in implementing new care practices. This “informal leader is the person who dictates the rules here” (E9, manager), against a manager who is absent, does not intervene or adopts a strategy of silence. Reprimands are always discussed, and eventually silenced, to avoid activating open conflict in the institutional space.

This invisible figure is not informal and charismatic, but an autocratic figure who leads through fear (“they are afraid of her” [E20, manager]), psychological manipulation (“she does not want to give it too much attention” [E9, social worker]) or a resistance figure (“she has been through everything, does not teach anything, she knows how to organise care work” [E10, manager]). The whole process is seen by the person who manages and assists as “very stressful” (E9, manager) and an “exhausting process” (E20, manager), and is compared to a “cat-and-mouse game” (E10, social worker). E10 nevertheless considers that in managing teams there is a difference between to ‘order’ and to ‘ask’. To ‘order’ involves a statutory attitude to fulfilling a particular task or activity; to ask (“asking to be done”) involves appreciation and recognition of the work undertaken, daily and continuously: “We don’t need to order, simply tell them how much we appreciate what is done every day” (E10, social worker). From this, a dimension intrinsic to care emerges: the need for recognition of care work by the person managing the organisation and the professional staff.

Quality aspirations – perspectives of care home managers

When asked ‘What factors determine the quality of care?’, the main factors that interviewees mention are lack of staff and poor working conditions. Managing staff with no qualifications who do not fit the job is seen as an everyday problem that will become more difficult in the future as care is a socially undervalued and poorly paid profession: “(it) does not reach 400, 500 euros per month” (E20, manager).

E20 (manager) believes that better pay alone would not change behaviour and caring practices, however:

“I think it’s a profession that is undervalued, very poorly paid and undervalued … but I’m also not sure whether they would do a better job if they were

paid double or triple. There could be more selection because there would be more demand, the financial issue could avoid many of the absences from work and they would feel more at the end of the month, in terms of salary, but when it comes to direct changes on provision of services, I don’t think so.” E10 (social worker) emphasises the need to change care practices in three ways: “continuous training” of care workers, with support group dynamics; professional recognition; and an organisational model with intermediate leaders with a vigilant attitude and a close, supportive approach:

“It comes from continuous training, there always being someone who says ‘Thank you, see you tomorrow’, ‘Okay, have a good day’. Being there, being present. But it has to be someone from above, not between colleagues or residents and a lot, a lot, of training, training with a civic-minded attitude.” E2 (social worker) notes “the lack of technical supervision, from the outside, to support the technical team which manages the organisation, particularly the authorities which oversee and supervise: social security’. E1 (manager) identifies three factors: personal training of the care worker, which “will make a huge difference in the care provided to the resident”; financial management; and public policies. The latter affects the quality of care, E1 (manager) believes, because organisational and financial aspects are shaped by national legislation, and the state regulates care institutions. She feels that legislation in Portugal is not in line with the social reality of the institutions, especially with the individuals now living in nursing homes (80% of whom are people with dementia), and she calls for changes in how the authorities assess services: “There are rules, there are policies, there are indicators, there are ratios, there are laws which influence the management of these organisations. They are totally out of touch with reality!” (E1, manager).

E9 (manager) summarises the official assessment and monitoring system as: bureaucratic (“evidence is paper, everything is treated the same way”); demanding (“it puts great pressure on the institution’s resources”); distant (“they don’t even look at the resident”); sporadic (“once a year”); and punitive (“it’s felt as policing, here comes a fine. It’s complete authoritarianism”). She feels that a systematic quality assessment model that is resident-centred and pedagogical is needed to eliminate inadequate care and a culture of omission: “I speak against myself; if there is no supervision, people will get a little out of hand”.

Care workers’ perspectives: between conflict and the

non-recognition of the work of care

This section presents some preliminary survey data, based on 41 self-reported responses from care workers. In the survey, care workers were asked about the factors that influence the quality of care work, conflict on the job, its nature and the reasons for it. The 41 care workers agreed that the major problems in care work are: lack of staff and being overworked (88%); conflict within work teams (83%); insufficient or poor training (80%); working conditions with inadequate equipment to support caring (76%); low wages (76%); a lack of technical supervision and feedback on their work (68%): and a lack of social recognition of their profession (73%).

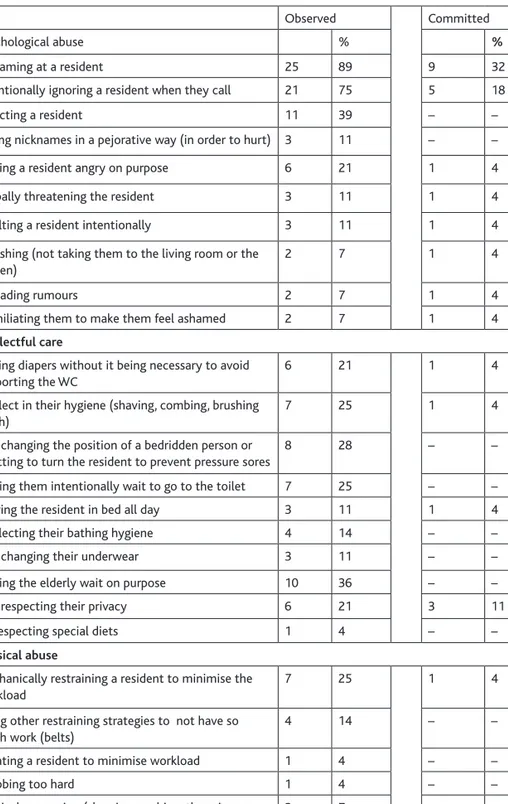

Although most conflicts reported by the care workers (67%) were disputes within care workers’ teams, this may be related to disparities between observed and actual acts of abuse and neglect by care workers. The most commonly observed acts against residents were: psychological (screaming at them) (89%); intentionally ignoring them (75%); rejecting them (39%); verbal abuse (deliberately making them angry) (21%); giving pejorative, intentionally hurtful, nicknames (11%); verbally threatening them (11%); insulting them (11%); spreading rumours (7%); humiliating them (7%); punishing them (by not taking them to the living room or garden) (7%); and neglectful care.

‘Neglectful’ care is related to care activities, in most cases, failing to provide necessary assistance: deliberately making them wait to go to the toilet (36%); unnecessarily putting them in incontinence pads to avoid taking them to the toilet (21%); not respecting their privacy (21%); neglecting their hygiene (shaving, combing, brushing teeth, bathing) (14%); and not changing their underwear (11%). ‘Omissions’ in care related to inadequate assistance: not changing the position of a bedridden person or omitting to turn them to prevent pressure sores (29%); leaving the resident in bed all day (11%); and disrespecting special diets (4%). Almost a third of study participants reported submitting residents to institutionalised practices: restraining a resident more than was necessary (25%); using other restraining strategies to have less work (belts) (14%); or sedating a resident to minimise workload (4%).

In the 41 interviews, 68% of the sample acknowledged employing some form of abuse or neglect. Estimates of observed and committed actions differed, however. The most commonly committed acts were psychological: screaming at a resident (32%), intentionally ignoring them (18%) and verbal abuse (4%). Neglectful care involved the omission of care, such as hygiene needs, including toileting, bathing, adequate clothing (each 4%) and respecting privacy (11%).

The preliminary survey data allowed the researcher to estimate practices of mistreatment, and interviews with some care workers enabled researchers to evaluate the care system. The care workers all felt that working conditions did not dignify their profession. The worst aspect for E5 (care worker) is the lack of recognition. Within the institutions, no distinction was made between those who take good care

Figure 1: Factors that influence the quality of care work

Table 4: Conducts observed and committed in the last 12 months

Observed Committed

Psychological abuse % %

Screaming at a resident 25 89 9 32

Intentionally ignoring a resident when they call 21 75 5 18

Rejecting a resident 11 39 – –

Giving nicknames in a pejorative way (in order to hurt) 3 11 – –

Making a resident angry on purpose 6 21 1 4

Verbally threatening the resident 3 11 1 4

Insulting a resident intentionally 3 11 1 4

Punishing (not taking them to the living room or the garden)

2 7 1 4

Spreading rumours 2 7 1 4

Humiliating them to make them feel ashamed 2 7 1 4

Neglectful care

Placing diapers without it being necessary to avoid supporting the WC

6 21 1 4

Neglect in their hygiene (shaving, combing, brushing teeth)

7 25 1 4

Not changing the position of a bedridden person or omitting to turn the resident to prevent pressure sores

8 28 – –

Making them intentionally wait to go to the toilet 7 25 – –

Leaving the resident in bed all day 3 11 1 4

Neglecting their bathing hygiene 4 14 – –

Not changing their underwear 3 11 – –

Making the elderly wait on purpose 10 36 – –

Not respecting their privacy 6 21 3 11

Disrespecting special diets 1 4 – –

Physical abuse

Mechanically restraining a resident to minimise the workload

7 25 1 4

Using other restraining strategies to not have so much work (belts)

4 14 – –

Sedating a resident to minimise workload 1 4 – –

Grabbing too hard 1 4 – –

Physical aggression (slapping, pushing, throwing an object at them)

2 7 – –

Financial abuse

and those in the profession ‘only for one reason’: “to earn a salary at the end of the month”. E13 defined her profession as “poorly paid, unjust and very sad. A job that is undervalued” (care worker).

The lack of social and institutional recognition of care work leads to conflicts within teams, as well as among professional staff and managers. E23 (care worker) stated:

“In my opinion, the problem is communication. There are no meetings; they don’t talk to us. I know that in other nursing homes, the situation is worse. Here, we are many, but sometimes in the morning, there are five people for 40 residents. It is impossible to take care of someone well. Everything is done in a rush and mechanically.”

E24 (care worker) believes that people who work with older people should be valued because of the physical and psychological wear and tear that caregiving entails, as well as its impact on the care worker’s health (physical and mental). On average, E15 (care worker) takes care of “seven to nine people each morning, depending on the days and on how many colleagues miss work”.

Inadequate ratios of residents to care workers causes personal care (eg the bathing of residents who are bedridden) to be spaced out over time, as E24 (care worker) explains: “Bathing is done every two weeks because there are many residents and that’s a lot of people to bathe.… It’s a lot of work. If we were to bathe everyone, we wouldn’t be done at 5.00 pm”.

What is bad care? E15 (care worker) describes it as:

“‘I don’t like that one, and I’m not going to lift him up’; ‘Want to go to the bathroom? Then do it in your pad’. I’ve worked nights and then when I arrive early in the morning people are in the same position, they have marks on their bodies from being in the same position and pads aren’t changed, they are full of pee. Sometimes, colleagues wait for the next shift and people get all soaked and pads or underwear aren’t changed. Or, other times, people who do not like meat or fish, and I often hear ‘You have to eat that or there will be no desert for you’.… You know, I’ve seen a lot of stuff and, to be honest, it’s very hard to swallow!”

E5 mentioned several reasons for conflict within care worker teams:

“It comes back to that issue of: we must like what we are doing. Some are [just] here to earn money at the end of the month because they can’t find another job.… I think there is a lack of training because when I entered the first nursing home, I didn’t know anything. I was learning from colleagues and what colleagues teach us is not always the right thing to do. I think there’s a lack of training and dialogue, above all, among care workers, managers and residents.” (E5, care worker)

E5 (care worker) offered some solutions: more demanding recruitment processes; a clearer care worker profile; and an accredited training process. E8 adds her love for the profession: do care assistants leave this profession due to poor working conditions (type of contract, salary) or the type of work? “No. It’s because they don’t like the

work. I usually say that this profession is like a marriage. To be happy isn’t enough; you have to love this. I’m here today for them [the elderly]!” (E8, care worker).

Discussion

This article gives voice to actors involved in the caregiving world. Common themes emerged from their narratives, including the lack of social recognition of care work as a profession, difficult working conditions and ambivalence about care practices. Both managers and care workers feel that the quality of care lies in the balance between personnel ratios and training; it is also recognised that excessive workloads and poor working conditions, coupled with high staff turnover and poor training and pay, are risk factors for inadequate care due to the physical and mental exhaustion of care workers. A care system not centred on persons (residents and care workers) has consequences for valuing care, affecting not only the quality of the care that these workers can offer, but also their physical and mental health, job satisfaction, and work environment.

The lack of recognition of care work (cleaning, washing, dressing, etc), low qualifications and poor pay give rise to tensions between normative expectations – of providing good care – and the reality of care practices. What is a good and bad practice? The frontiers between poor care (insufficient, deficient or inadequate care) lead to abuse and neglect and become tenuous in an institutional context, but they are difficult to define and measure. This distinction is all the more difficult when the system is characterised by a lack of recognition of care work, omissions or limited monitoring of care practices in a conflictual organisational climate with poor communication, which can lead to the institutionalisation of a care omission culture. These factors are likely to reduce care quality and increase the risk of neglectful care in daily practices.

Severe omissions in personal care activities were identified in daily practices in the three nursing homes, based on interviews and observations, which are considered as abusive acts in institutions (Dixon et al, 2009; Drennanet et al, 2012): use of physical restraints and depriving residents of dignity and choice over daily matters. Physical restraint has emerged as potentially problematic in nursing homes. Elder abuse, by use of physical restraints, may be perceived as more acceptable or justifiable in situations where the older person has a mental health problem and is difficult to care for, or is at risk of falling (Melchiorre et al, 2014: 926). Although legislation regulates restraint in Portugal (DGS, 2011) and its overuse in an institutional context is recognised in institutional practices, it is also sometimes justified to minimise workloads or in cases of a shortage of care workers. These examples are difficult to separate from a more general quality care problem rooted in broader facility practices and policies (Hawes, 2003). It is easier to blame care workers, who have fewer resources, than an organisational system that crosses the hierarchical chain: regulators, managers, professional staff and those who carry out care.

A care system, based on power relations/domination and socially marginalised groups, who face discrimination in the workforce (Tronto, 2010), can become a counter-power within organisations. These informal powers set new rules in care work, against institutional rules, sometimes with serious impacts on the physical and psychological well-being of residents. The role of informal powers in care practices remains under-studied due to their invisibility, and further qualitative research is

needed to understand how power relations inside organisations interfere with care practices.

Low public investment in long-term care and an efficient care quality-control system, with ‘poor supervision’ and a ‘closed culture of care’, are recognised as situational risk factors (McDonald et al, 2012; Phelan, 2015). The fragility of the quality care monitoring system that is carried out in Portuguese institutions can be explained by the role of social security, which does not interfere ‘in operational issues, and, in its role, as supervisory agent, limits inspections to assessments of technical requirements of facilities to keep licenses active’ (Lopes, 2017: 71). Indeed, in Portugal, public care regulation and quality management4 is far removed from the trend in

Europe of ‘moving away from an inspection-only approach to a quality management approach that combines inspection with advice and self-assessment reports with an effective internal quality management system’ (EU, 2010: 3).

This article has limitations as the sample comprised only three nursing homes and the data obtained are exploratory and preliminary. Although the study included resident interviews and observation of daily life, the focus of this article is on the perspectives of care workers, professional staff and managers. It is also important to listen to the real voices of older people, who are key actors in the care process system. The analysis offers some new areas for further exploration in terms of data collection and monitoring practice development, and can guide future studies.

Funding

This work was supported by the Foundation for Science and Technology (Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia) in Portugal (Grant SFRH/BPD/107722/2015).

Conflict of interest statement

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest. Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for providing invaluable comments that helped to improve my arguments, and editorial assistance at the International Journal of

Care and Caring.

Notes

1. The confederation of non-profits provides a list, with salary rates of all categories of

workers, in Ministério do Trabalho, Solidariedade e Segurança Social (2017).

2. A multi-method study was developed, with the aim of analysing the relationships

between the organisation of nursing homes, the interpersonal features of care providers and their relation with home residents’ quality of life. Elder abuse and neglect is one of the areas analysed.

3. The second phase of the project involved data collection in 16 nursing homes. Interviews

were conducted with 16 managers, 40 nursing home-care assistants and 20 professional staff. A self-administered questionnaire was given to 280 nursing home-care assistants, with a response rate of 70% achieved. The adult social care outcomes toolkit (ASCOT) – Care homes version (CH3) (non-official) – was also applied, from which the characteristics of 120 elderly people were obtained.

4. As Sardinha et al (2015: 131) state: ‘The number of certified institutions is around

of the institutions are still outside of any quality certification system (more than 4500 institutions)’.

References

Castle, N., Ferguson-Rome, J. and Teresi, J. (2015) Elder abuse in residential long-term care: an update to the 2003 National Research Council Report, Journal of

Applied Gerontology, 34(4): 407–43.

Connidis, I. and McMullin, J. (2002) Sociological ambivalence and family ties: a critical perspective, Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(3): 558–67.

DGS (Directorate-General for Health) (2011) Preventive measures of aggressive/violent

behaviour of patients, Guideline no. 021/2011, Lisbon: DGS.

Dixon, J., Biggs, S., Tinker, A., Stevens, M. and Lee, L. (2009) Abuse, neglect and loss

of dignity in the institutional care of older people, London: National Centre for Social

Research.

Donabedian, A. (1980) Explorations in quality assessment and monitoring, Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press.

Drennanet, J., Lafferty, A., Treacy, M., Fealy, G., Phelan, A., Lyons, I. and Hall, P. (2012) Older people in residential care settings: Results of a national survey of staff–resident

interactions and conflicts, Dublin: University College Dublin and National Centre

for the Protection of Older People.

EC (European Commission, DG Employment, Social Affairs and Equal Opportunities) (2010) Peer review: Achieving quality long-term care in residential facilities, short report, E. Murnau, Germany, 18–19 October.

EU (European Union) (2010) Long-term care for the elderly: Provisions and providers in

33 European countries (eds F. Bettio and A. Verashchagina), EU Expert Group on

Gender and Employment (EGGE), Rome: Fondazione G. Brodolini.

Eurofound (2017) In-work poverty in the EU, Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) (2017) Gender Equality Index 2017:

measuring gender equality in the European Union 2005-2015 – report, Brussels: European

Commission.

Ferreira, V. (2010) Elderly care in Portugal: provisions and provided care, report presented to the European Commission Directorate – General Unit G1 Equality between Women and Men.

GEP (Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento, Lisbon) (2017) Carta Social, Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento, Lisbon: Ministério da Solidariedade, Emprego e Segurança Social.

Gil, A.P. (2010) Heróis do quotidiano: Dinâmicas familiares na dependência [Every day

heroes: Family dynamics in dependency], Lisbon: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian and

Fundação para a Ciência e para a Tecnologia.

Hawes, C.( 2003) Elder abuse in residential long-term care settings: what is known and what information is needed?, in R. Bonnie and R. Wallace (eds) Elder mistreatment:

Abuse, neglect, and exploitation in an ageing America, Washington, DC: The National

Academies Press, pp 446–91.

Hussein, S. (2017) ‘We don’t do it for the money’ … the scale and reasons of poverty-pay among frontline long-term care workers in England, Health and Social Care in

Hussein, S. (2018) Job demand, control and unresolved stress within the emotional work of long term care in England, International Journal of Care and Caring, 2(1): 89–107.

Hyde, P., Burns, D., Killett, A., Kenkmann, A., Poland, F. and Gray, R. (2014) Organisational aspects of elder mistreatment in long-term care, Quality in Ageing

and Older Adults, 15(4): 197–209.

Kamavarapu, Y.S., Ferriter, M., Morton, S. and Völlm, B. (2017) Institutional abuse: characteristics of victims, perpetrators and organisations. A systematic review,

European Psychiatry, 40: 45–54.

Kelly, C. (2017) Care and violence through the lens of personal support workers,

International Journal of Care and Caring, 1(1): 97–113.

Lafferty, A., Phelan, A. and Fealy, G. (2015) Residential care standards: Towards a

risk-management framework for preventing elder mistreatment, Dublin: National Centre for

the Protection of Older People.

Lopes, A. (2017) Long-term care in Portugal – quasi-privatization of a dual system of care, in B. Greve (ed) Long-term care for the elderly in Europe – Development and

prospects, Social Welfare Around the World, London: Routledge, pp 59–74.

Malmedal, W., Hammervold, R. and Saveman, I. (2014) The dark side of Norwegian nursing homes: factors influencing inadequate care, The Journal of Adult Protection, 16(3): 133–51.

McDonald, L., Beaulieu, M., Harbinson, J., Hirst, S., Lowenstein, A., Podnieks, E. and Wahl, J. (2012) Institutional abuse of older adults: what we know, what we need to know, Journal of Elder Abuse and Neglect, 24(2): 138–60.

Melchiorre, M., Penhale, B. and Lamura, G. (2014) Understanding elder abuse in Italy: perception and prevalence, types and risk factors from a review of the literature,

Educational Gerontology, 40(12): 909–31.

Ministério do Trabalho, Solidariedade e Segurança Social (2017) Boletim do Trabalho

e Emprego, no. 39, Lisbon: Gabinete de Estratégia e Planeamento.

Noelker, L.S. and Harel, Z. (2001) Humanizing long-term care: forging a link between quality of care and quality of life, in L.S Noelker and Z. Harel (eds) Linking

quality of long-term care and quality of life, Canada: Springer Publishing Company.

Nolan, M.R., Davies, S., Brown, J., Keady, J. and Nolan, J. (2004) Beyond ‘person-centred’ care: A new vision for gerontological nursing, Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(1): 45–53.

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2013) A good

life in old age? Monitoring and improving quality in long-term care, OECD Health Policy

Studies, Paris: OECD Publishing, http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264194564-en OECD (2016) Long-term care data: Progress in data collection and proposed next steps,

DELSA/HEA/HD (2016)3, Paris: Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs Health Committee.

OECD (2017) Health at a glance 2017: OECD indicators, Paris: OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/health_glance-2017-en

Patton, M.Q. (2002) Qualitative research and evaluation methods, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Phelan, A. (2015) Protecting care home residents from mistreatment and abuse: on the need for policy, Risk Management and Healthcare Policy, 8: 215–23.

Rodrigues, R., Huber, M. and Lamura, G. (eds) (2012) Facts and figures on healthy

ageing and long-term care, Vienna: European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and

Research.

Sardinha, B., Soares, A., Marques, B. and Dias, O. (2015) Definição de um Modelo

Nacional de Reconhecimento dos Sistemas da Qualidade nas Instituições de Serviço Social,

Setúbal: Instituto Politécnico de Setúbal.

Scheil-Adlung, X. (2015) Long-term care (LTC) protection for older persons: A review

of coverage deficits in 46 countries, European Social Survey working paper no. 50,

Geneva: International Labour Office.

Shulmann, K., Gasior, K., Fuchs, M. and Leichsenring, K. (2016) The view from

within: ‘Good’ care from the perspective of care professionals – Lessons from an explorative study, Policy Brief 2, Vienna: European Centre.

Schutz, A. (1998) Éléments de Sociologie Phénoménologique [Elements of phénoménologique

Sociology], Logiques Sociales, Paris: L´Harmattan.

Tronto, J. (2010) Creating caring institutions: politics, plurality and purpose, Ethics

and Social Welfare, 4(2): 158–71.

Yeandle, S. (2016) Caring for our carers: an international perspective on policy developments in the UK, Juncture, 23(1): 57–62.

Yeandle, S., Chou, Y.C., Fine, M., Larkin, M. and Milne, A. (2017) Care and caring: interdisciplinary perspectives on a societal issue of global significance, International