FREE THEMES

1 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Odontologia, Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco. Av. da Engenharia, Cidade Universitária. 50670-420 Recife PE Brasil. marcilia.paulino@ yahoo.com.br 2 Centro de Ciências da Saúde, Universidade Federal da Paraíba. João Pessoa PB Brasil.

3 Departamento de Biologia Estrutural e Funcional Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Campinas SP Brasil.

Prevalence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular

disorders in college preparatory students: associations

with emotional factors, parafunctional habits,

and impact on quality of life

Abstract The aim of this study was to evaluate the prevalence of temporomandibular disorders (TMD) signs and symptoms, its correlation with gender, parafunctional habits, emotional stress, anxiety, and depression and its impact on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQL) in college preparatory students at public and private insti-tutions in João Pessoa, Paraíba (PB). The sample consisted of 303 students. Presence of TMD symp-toms was determined by an anamnesis question-naire containing questions related to the presence of parafunctional habits and emotional stress. A simplified clinical evaluation protocol was used. Anxiety and depression were determined with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale and the OHRQL using the short version contained in the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP-14). The Chi-square, Fisher Exact, Mann Whitney, and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed. Presence of signs and symptoms of TMD was statistically as-sociated (p ≤ 0,05) with female gender, parafunc-tional habits, emoparafunc-tional stress, and anxiety, and represented greater impairment of the OHRQL. The physical pain domain was the most affected. The increased prevalence of signs and symptoms of TMD among college preparatory students indi-cates that there is a need for education and clari-fication among teachers and students to improve early diagnosis and to prevent the problem.

Key words Temporomandibular joint disorders,

Adolescence, Habits, Anxiety, Quality of life

Marcilia Ribeiro Paulino 1

Vanderlucia Gomes Moreira 2

George Azevedo Lemos 3

Pâmela Lopes Pedro da Silva 2

Paulo Rogério Ferreti Bonan 2

Paulino MR Introduction

The American Academy of Orofacial Pain (AAOP) defines temporomandibular disorder (TMD) as a group of painful and/or dysfunctional conditions related to the muscles of mastication, temporo-mandibular joints (TMJs), and related structures1. The major signs and symptoms related to these disorders are pain in the TMJ region and palpation of the muscles of mastication, ear pain and other otologic signs, joint noise, mandibu-lar misalignment, limited mouth opening, tired-ness and muscular fatigue, headaches, and dental wear2-6.

TMD has a multifactorial etiology, including genetic and behavioral factors, direct and indirect trauma, psychological factors, and postural and parafunctional habits2,7-9. However, the effects of these etiological agents are controversial and re-main not completely understood.

The biopsychosocial model has recently gained attention, promoting a wide discussion on the influence of emotional factors on the eti-ology of TMD8-12. Thus, emotional distress, stress, anxiety, and depression have been linked to the presence of the signs and symptoms of this dis-order in several populations9,11,13-15. These factors, especially stress and anxiety, may cause muscular hyperactivity and the development of parafunc-tional habits, leading to microtraumas of the TMJ and muscular lesions16-18.

Recent studies have also shown that the symp-toms of TMD, especially pain, can increase the level of physical and mental harm, with negative effects on quality of life (QL)19-23. In addition, the literature has shown that the severity of TMD is reflected in the decrease in oral health-related quality of life (OHRQL)23.

In this study, we address the presence of signs and symptoms of TMD in a population of col-lege preparatory students, mainly adolescents in the last year of high school. According to Godoy et al.24, this phase is often characterized as a peri-od of confusion and ambiguity due to the youths’ needs to begin to become part of the adult world and changes to their bodies, which affect their role in society. In addition, the college entrance exam, which is considered to be a competitive and stressful system for acceptance to Brazilian uni-versities, may be reflected by increased social and familial pressure, anxiety, stress, and other emo-tional disorders closely related to a diagnosis of

TMD25,26.

In addition, several studies have investigated the prevalence of TMD and associated factors

in children3,7,14,27, adolescents2,4,16, college stu-dents9,15,18,23,28, adults10,12,21,29 and elderly30, howev-er few information is available about college pre-paratory students, subjected to high psychosocial burden, including psychological and physical manifestations of stress and anxiety24,26,31,32.

Thus, the aim of this study is to evaluate the presence of signs and symptoms of TMD, its cor-relation with gender, reports of parafunctional habits, emotional stress, anxiety, and depression and its effects on OHRQL in college preparatory students enrolled in their last year of high school or college entrance exam courses in João Pessoa, Paraíba (PB).

Materialsandmethods

This research was a non-probability cross-sec-tional study performed using college preparatory students in the third year of high school or tak-ing college entrance exam preparation courses in public and private institutions in the city of João Pessoa (PB) in 2011. The sample consisted of 303 volunteers from both sexes, between 15 to 25 years of age, who agreed to participate in the study. Students who did not sign (or whose guardians did not sign) the consent form, stu-dents who had orthodontic treatment (attached or removable appliance), and students who had received treatments for TMD or other orofacial pain were excluded.

In concordance with the requirements and criteria established by Resolution num. 196/96 of the National Health Council (NHC), the project was presented to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) of the Lauro Wanderley University Hospi-tal at the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB).

Datacollection

Permission slips were provided in duplicate to 10 high schools (five private and five public), together with a copy of the research study. Insti-tutions were selected by convenience from all of the high schools and pre-entrance exam cours-es in the city of João Pcours-essoa (PB). Permission to perform the study was given in only three private and three public institutions.

Questionnaires were given during the break between classes, which varied between 20 and 30 minutes, during both sessions (morning and after-noon), depending on the availability of each school.

e C

ole

tiv

a,

23(1):173-186,

2018

to conduct the surveys and the inclusion in the study of minors whose participation was depen-dent on the consent form being signed by their legal guardians.

EvaluationofthepresenceofTMD

symptomsandparafunctionalhabits

A self-reporting questionnaire containing objective questions on the presence of parafunc-tional habits and the “DMF anamnestic index” from Fonseca et al.33 was used to evaluate the se-verity of the TMD and the need for treatment.

The DMF index consisted of 10 questions related to symptoms of TMD, with three possi-ble answers for each question: “yes,” “no,” or “oc-casionally,” which were assigned values of 10, 0, and 5, respectively. The sum of the values for the responses allowed the population to be classified according to the severity of the TMD, based on the reported symptoms: absent (0-15), mild (20-40), moderate (45-65), or severe (70-100). The data from the DMF anamnesis index also allowed the sample to be classified by need for treatment, based on the TMD symptoms reported, as: “no need for treatment” (absent or mild TMD) and “treatment needed” (moderate to severe TMD).

For parafunctional habits, the volunteers were asked to indicate the habits that they per-formed most often on a multiple-choice question containing options previously selected from the literature4,16,34. Participants were informed that they could mark more than one option.

Evaluationforthepresenceofclinical

signsofTMD

Two previously calibrated examiners, with in-ter and intra-examiner Kappa coefficients of 0.82 and 0.95, respectively, performed the simplified clinical exam on the youths in rooms selected by the institutions. The evaluation was performed with the students sitting in a chair with a back-rest with an erect back, legs and feet parallel and firmly placed on the ground under ambient light. Examiners also used proper personal protection equipment (gloves, masks, protective eyewear, and protective clothing).

The following parameters were evaluated: Muscular sensitivity: the masseter (lower, middle, and upper thirds) and temporal (ante-rior, middle and posterior thirds) muscles were palpated with a pressure of approximately 1.0 kg/

cm223,35, and the resistive protrusion method was

used to analyze the lateral pterygoid. A total of

seven sites were analyzed by palpation on each side (three temporal, three masseter, and one lat-eral pterygoid), resulting in 14 muscular palpa-tion sites per volunteer. Pain was quantified using objective values in which “0” indicated no pain, “1” tenderness was reported by the volunteer, “2” tenderness with physical manifestations, and “3” tenderness with evasion by the volunteer23,35.

Jointsensitivity: Lateral palpation of the TMJ was performed with the volunteer at rest, and posterior palpation of the TMJ was palpated with maximum opening. Both were conducted with a pressure of approximately 0.5 kg/cm223,35. Pain was quantified using objective values, as de-scribed above23,35.

Joint Noise: The volunteers were asked to open and close their mouths three times. The examiner’s index fingers were positioned over the TMJs, allowing the evaluation of presence/ absence of clicking or crepitus (grinding sound during mandibular movement) to be detected. The presence of TMJ noise was considered when they were reproducible in at least two of three movements23,35.

Active mouth opening: With the patient in maximum opening, the distance between the edges of the upper and lower middle incisors was measured, in millimeters (mm), using a caliper (NSK, Nippon Sokutei, Japan). In addition, the vertical overlap was also measured by vertical su-perposition of the upper incisors on the lower, with the volunteer in maximal intercuspation, using a caliper. The sum of the two measure-ments (opening and vertical overlay) provided the active mouth opening of each volunteer. The size of the active mouth opening was classified as restricted opening (< 40 mm), normal open-ing (40-59 mm), or hypermobility (more than 60

mm)23,35.

Jaw movement alterations: The volunteers were asked to open and close their mouths three times, allowing the presence or absence of man-dibular deviations (the mandible deviates during opening but returns to the midline when opened completely) or deflections (when the mandible is off the midline through maximal opening). The presence of jaw movement alterations was de-fined when they were reproducible in at least two of three movements23,35.

The presence of clinical signs allowed the vol-unteers classification as follows:

SignsofmuscularTMD: two or more sites of muscular sensitivity;

Paulino MR mouth opening or mandibular hypermobility, or

altered movement);

SignsofmixedmuscularandarticularTMD: the presence of two or more sites with muscular pain and simultaneous joint signs.

Analysisofthepresenceofanxiety,

depression,andemotionalstress

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale, translated into and validated in Portuguese, was used to evaluate the frequency of anxiety and depression36. The scale includes 14 items, seven that address anxiety (HADS-A) and seven that address depression (HADS-D). Each of these items can receive 0 to 3 points, resulting in a maximum score of 21 points for each subscale. The total scores in each subscale are classified us-ing the followus-ing cutoffs: no anxiety from 0 to 8 and anxiety ≥ 9; no depression 0 to 8 and depres-sion ≥ 9.

The volunteers also responded, in the same questionnaire, to a question related to the pres-ence/absence of emotional stress and indicated their stress level on an Analog Visual Scale (AVS) from 0 to 10.

OralHealth-RelatedQuality

ofLifeAnalysis

OHRQL was measured using the Oral Health Impact Profile (OHIP), in a shortened and vali-dated Portuguese version (OHIP-14)37,38. The questionnaire consists of 14 questions, two for each of the seven survey dimension. Each ques-tion has five possible answers: never, rarely, sometimes, often, and always for 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 points, respectively. The sum of the ordinal re-sponses gives the total OHIP-14 score, which can range from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating a larger negative impact for oral health37,38.

The OHIP-14 comprises seven areas of oral health with two questions for each area (func-tional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort, physical impairment, psychological impairment, social impairment, and disability). The points from each of the seven OHIP-14 areas can range from 0 to 8 points, with higher scores representing more harm.

Dataanalysis

The data were recorded and tabulated in the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0, and analyzed by descriptive and by

inferential statistics. Frequencies and percentages were used for descriptive analysis, and the follow-ing non-parametric tests were used for inferen-tial statistical analysis: Chi-square, Fisher exact, and significance calculations for identifying cor-relations between the variables. For the OHIP-14 scores, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test showed that the data were not normally distrib-uted; thus, the non-parametric Mann-Whitney and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare the means of the OHIP-14 scores in the different groups analyzed. For all statistical tests, a 95% confidence interval and a 5% (p < 0.05) signif-icance level were adopted.

Results

Samplecharacterization

A total of 303 students were evaluated in this study. From this sample, most were female (69%), between 15 to 19 years of age (93.1%), and from public schools (74.6%). Based on the DMF index, some level of TMD was identified in 89.8% of the participants, of which 50.2% had mild TMD, 33.0% moderate and only 6.6% se-vere. 39.6% of volunteers exhibited an active need for treatment (moderate and severe TMD). The TMD severity and need for treatment were determined by the DMF index according to the TMD symptoms reported. However, the physical exam showed the presence of clinical TMD signs in 56.4% of the sample. 31.0% showed clinical signs of articular TMD, 11.2% signs of muscular TMD and 14.2% combined signals of articular and muscular TMD.

Parafunctional habits were highly prevalent (95.4%), but the variables of emotional stress, anxiety, and depression were found in 82.5%, 40.3%, and 10.6% of the analyzed population, respectively.

Factorsassociatedwiththepresence

ofsignsandsymptomsofTMD

e C

ole

tiv

a,

23(1):173-186,

2018

based on the symptoms of TMD reported) was statistically associated with the female gender (p < 0.001), reported parafunctional habits (p = 0.039), reported emotional stress (p < 0.001), anxiety (p < 0.001), and depression (p < 0.001) (Table 2). However, the presence of clinical signs of TMD following the physical exam was only associated with female gender (p < 0.001) and anxiety (p < 0.001) (Table 3).

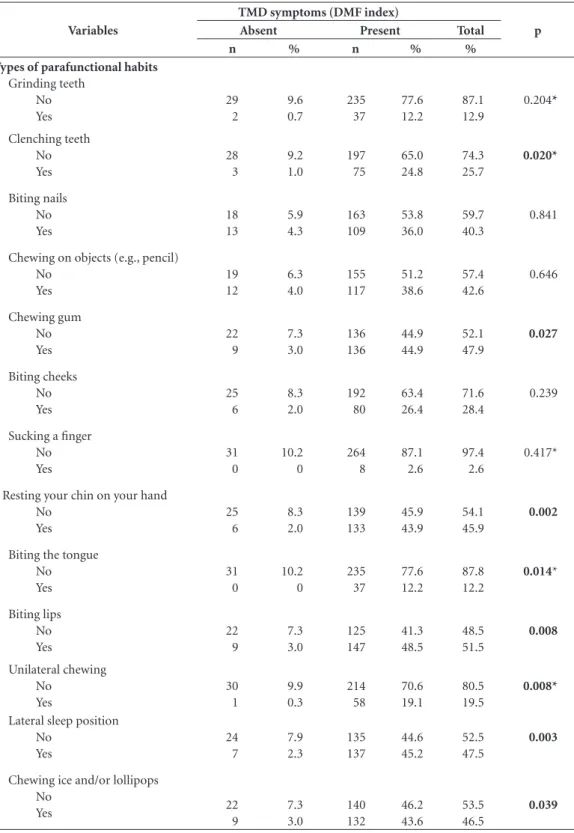

When the symptoms of TMD (DMF index) was compared to each type of parafunctional habit, we found a statistically significant associa-tion with the following habits: chewing gum (p = 0.027); clenching teeth (p = 0.020); resting your chin on your hand (p = 0.002); biting the tongue (p = 0.014); biting lips (p = 0.008); unilateral chewing (p = 0.008); lateral sleeping (p = 0.003); and chewing ice and/or lollipops (p = 0.039) (Ta-ble 4).

ImpactofTMDonoralhealth-related

qualityoflife

Table 5 shows that volunteers with TMD symptoms (DMF index) had a statistically higher OHIP-14 score than volunteers without

symp-toms (p < 0.001), suggesting a negative impact on OHRQL. The average OHIP-14 score was statis-tically higher in the group of volunteers needing treatment than in the group not needing treatment (p < 0.001), and the more severe the TMD (DMF index) was, the larger the impact on OHRQL.

Regarding the physical exam, volunteers with clinical signs of articular, muscular, or mixed TMD had higher OHIP-14 scores than volunteers with no signs of TMD, but this difference was only significant for those with mixed signs of articular and muscular TMD (p = 0.01) (Table 4). Of the OHIP-14 seven domains, physical pain was the domain that presented the highest impact on the groups with clinical signs of articular (p = 0.033), muscular (p = 0.019), and mixed (p < 0.001) TMD.

Discussion

In this study it was proposed to evaluate the prev-alence of signs and symptoms of TMD and its associated factors in a sample of students in the last year of high school and that would be sub-mitted to the college entrance examination. The

Table 1. Association between the presence of TMD symptoms (DMF index) and the variables gender, type of

educational institution, presence of parafunctional habits , stress report, presence of anxiety and depression.

Variables

TMD symptoms (DMF index)

p

Absent Present Total

n % n % %

Gender Female Male

11 20

3.6 6.6

198 74

65.3 24.4

69.0 31.0

< 0.001

Educational institution Private

Public

4 27

1.3 8.9

73 199

24.1 65.7

25.4 74.6

0.065*

Parafunctional habits No

Yes

7 24

2.3 7.9

7 265

2.3 87.5

4.6 95.4

< 0.001

Presence/report of stress No

Yes

17 14

5.6 4.6

36 236

11.9 77.9

17.5 82.5

< 0.001

Anxiety No Yes

31 0

10.2 0

150 122

49.5 40.3

59.7 40.3

< 0.001*

Depression No Yes

29 2

9.6 0.7

242 30

79.9 9.9

89.4 10.6

0.337*

Paulino MR

Table 3. Association between the presence of clinical signs of TMD (simplified clinical exam protocol) and the

variables: gender, type of educational institution, presence of parafunctional habits, stress report, presence of anxiety and depression.

Variables

Clinical signs of TMD (simplified clinical exam protocol)

Absent Present Total p

n % n % %

Gender

Female 77 25.4 132 43.6 69.0 < 0.001

Male 55 18.2 39 12.2 31.0

Teaching institution

Private 32 10.6 45 14.8 25.4 0.681

Public 100 33.0 126 41.6 74.6

Parafunctional habits

No 10 3.3 5 1.7 5.0 0.064

Yes 122 40.3 166 54.4 95.0

Presence/report of stress

No 24 7.9 29 9.6 17.5 0.781

Yes 108 35.6 142 36.9 82.6

Anxiety

No 97 32.0 91 30.0 62.0 < 0.001

Yes 35 11.6 80 26.4 38.0

Depression

No 120 39.6 153 50.5 90.1 0.678

Yes 12 4.0 18 5.9 9.9

Chi-square test. Statistically significant, p < 0.05.

Table 2. Association between the “treatment need” (DMF index) and the variables gender, type of educational

institution, presence of parafunctional habits , stress report, presence of anxiety and depression.

Variables

Need for TMD treatment (DMF index)

Absent Present Total p

n % n % %

Gender

Female 107 35.3 102 33.7 69.0 < 0.001

Male 76 25.1 18 5.9 31.0

Educational institution

Private 43 14.2 34 11.2 25.4 0.344

Public 140 46.2 86 28.4 74.6

Parafunctional habits

No 12 4.0 2 0.7 4.7 0.039*

Yes 171 56.4 118 38.9 95.3

Presence/report of stress

No 44 14.5 9 3.0 17.5 < 0.001

Yes 139 45.9 111 36.6 82.5

Anxiety

No 136 44.8 45 14.9 59.7 < 0.001

Yes 47 15.5 75 24.8 40.3

Depression

No 175 57.8 96 31.7 89.5 < 0.001

Yes 8 2.6 24 7.9 10.5

e C ole tiv a, 23(1):173-186, 2018

choice of this specific group is justified by the ab-sence of further studies related to TMD in this specific sample, demonstrably subjected to high emotional burden, including anxiety, anguish,

restlessness and stress26,31,32. Furthermore, recent studies have shown that these emotional factors may be closely related to the diagnosis and pro-gression of TMD9,11,13-15.

Table 4. Association of the presence of TMD symptoms with each parafunctional habit.

Variables

TMD symptoms (DMF index)

p

Absent Present Total

n % n % %

Types of parafunctional habits

Grinding teeth No Yes 29 2 9.6 0.7 235 37 77.6 12.2 87.1 12.9 0.204* Clenching teeth No Yes 28 3 9.2 1.0 197 75 65.0 24.8 74.3 25.7 0.020* Biting nails No Yes 18 13 5.9 4.3 163 109 53.8 36.0 59.7 40.3 0.841

Chewing on objects (e.g., pencil) No Yes 19 12 6.3 4.0 155 117 51.2 38.6 57.4 42.6 0.646 Chewing gum No Yes 22 9 7.3 3.0 136 136 44.9 44.9 52.1 47.9 0.027 Biting cheeks No Yes 25 6 8.3 2.0 192 80 63.4 26.4 71.6 28.4 0.239

Sucking a finger No Yes 31 0 10.2 0 264 8 87.1 2.6 97.4 2.6 0.417*

Resting your chin on your hand No Yes 25 6 8.3 2.0 139 133 45.9 43.9 54.1 45.9 0.002

Biting the tongue No Yes 31 0 10.2 0 235 37 77.6 12.2 87.8 12.2 0.014* Biting lips No Yes 22 9 7.3 3.0 125 147 41.3 48.5 48.5 51.5 0.008 Unilateral chewing No Yes 30 1 9.9 0.3 214 58 70.6 19.1 80.5 19.5 0.008*

Lateral sleep position No Yes 24 7 7.9 2.3 135 137 44.6 45.2 52.5 47.5 0.003

Chewing ice and/or lollipops No Yes 22 9 7.3 3.0 140 132 46.2 43.6 53.5 46.5 0.039

Paulino MR

In the present study, sample consisted mainly of female students from public schools. These re-sults are due to the lack of responses for permis-sion to collect data and negativity in some pri-vate institutions. Add to this the better reception among female volunteers, and it was difficult to obtain a balanced sample for gender and type of teaching institution.

The prevalence of symptoms and clinical signs of TMD were determined in this study by the “DMF index”34 and simplified clinical exam-ination2,4,16,23. The DMF index sorts the volun-teers in categories based on the severity of TMD symptoms and the absence/presence of treatment need, but does not provide diagnostic classifica-tion39. Another limitation arises from its scoring system, since if three affirmative responses are attributed to questions about headache, cervical pain and perception of emotional tension, the volunteer will be classified as mild DTM carrier, and these symptoms may occur an isolated man-ner, without any relation to this dysfunction39.

However, the DMF index brings some ad-vantages such as simplicity, speed of aplication and low cost, enabling it use in epidemiological studies, for plotting population profiles, for pa-tients screening or, in the assessment of quality of

life23,39,40, being used in several studies to evaluate

the prevalence of TMD symptoms18,41-43. Campos et al.40 suggested the suppression of some of the DMF index questions, which would increase its reliability. However, the removal of this questions would make the instrument very similar to the AAOP questionnaire, would not allow the clas-sification of the severity of symptoms of TMD. Besides, the validity trial of the modified index was not yet performed. Thus, we decided to use the DMF index in its original version.

The simplified clinical examination

proto-col2,4,16,23,35 allows the evaluation of the presence of

joint, muscle or mixed TMD clinical signs. This clinical evaluation protocol is quick and simple, allowing its use in studies with larger samples, complementing the information of anamnesis questionnaire33. However, it does not provide a standardized diagnostic classification for TMD. Currently, the Research Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (RDC/TMD), and its most recent version, the Diagnostic Cri-teria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/ TMD) are the “gold–standard” instruments available in the literature for TMD evaluation, providing an accurate diagnosis this dysfunc-tion44. However, RDC/TMD is a complex instru-ment, making its use difficult in large samples, and the calibration of examiners is

time-con-Table 5. Statistical comparisons between OHIP-14 scores for the presence of TMD symptoms (DMF index),

severity of TMD (DMF index), need for treatment (DMF index) and clinical signs of TMD (simplified clinical examination protocol).

TMD Classification Mean OHIP-14 ± SD p

TMD symptoms (DMF index)

Absent 5.42 ± 4.581

< 0.001*

Present 11.65 ± 8.482

Need for treatment (DMF index)

Absent 8.02 ± 6.531

< 0.001*

Present 15.53 ± 8.855

Severity of TMD (DMF index)

No TMD 5.42 ± 4.581

0.019**

Mild TMD 8.60 ± 6.745

Moderate TMD 14.54 ± 8.474 < 0.001**

Severe TMD 20.45 ± 9.512 < 0.001**

Clinical signs of TMD (simplified clinical examination protocol)

No TMD 9.98 ± 8.046

0.320** Clinical signs of articular TMD 10.52 ± 8.421

Clinical signs of muscular TMD 12.26 ± 8.743 0.127** Clinical signs of mixed articular and muscular TMD 14.30 ± 8.348 0.01**

e C

ole

tiv

a,

23(1):173-186,

2018

suming. In this study, all evaluations were con-ducted with students during the interval between classes. This is a short period, around 20-30 min-utes, which would difficult the application of the RDC/TMD. Furthermore, the DC/TMD was not yet translated or validated for Portuguese, which difficult it use in research in Brazil. The difficulty in establishing an “ideal” protocol of epidemio-logical evaluation of TMD can be confirmed by the absence of representative data of TMD preva-lence in the Brazilian population, since, until this moment, no TMD protocol exam has yet been included in the National Oral Health Survey - the “SB Brasil”, performed in 2003 and 2010.

Considering the facts previously described and the limitations of the instruments used in this study, a high prevalence of clinical signs and symptoms of TMD by the anamnestic DMF in-dex (89.8%) and the physical exam (56.4%) was observed. In addition, a large portion of this population showed an active “treatment need” (39.6%). It is noteworthy that the need for treat-ment was based on reported symptoms33 rather than the diagnosis of TMD. The prevalence of the signs and symptoms of TMD in adolescents varies widely due to individual differences, sam-ple variability (heterogeneous age groups, samsam-ple size, and selection criteria), and different evalua-tion methods27,45. Thus, epidemiological studies in children have found a TMD prevalence be-tween 21-74%4,16,28. In this study, the age range varied between 15-25 years of age, including adolescents and young adults. Indeed, the latter group had a higher prevalence of TMD signs and symptoms5,41,43, supporting the results found.

The majority of volunteers had mild TMD (50.2%), and only 6.6% had severe TMD. It is noteworthy that the severity of TMD was based on symptoms reported33 by volunteers. A higher percentage of individuals with mild TMD was also observed by Medeiros et al.18, Pedroni et al.41, Oliveira et al.42 e Bonjardim et al.43. Considering the clinical exam protocol, the clinical signs of articular TMD were most prevalent (31%), fol-lowed by signs of mixed articular and muscu-lar TMD (14.2%) and muscumuscu-lar TMD (11.2%). Consistent with our results, epidemiological studies have shown a prevalence of joint sounds in approximately 23-47% and joint pain in 16-45% of children and adolescents2,4,5,24. Further-more, muscular sensitivity to palpation was re-corded in 23-43% of this population2,4,16.

In the present study, female gender was strongly associated with the presence of symp-toms and clinical signs of TMD (DMF index and

simplified clinical examination), as with “treat-ment need” (DMF index). A higher prevalence of TMD in females has been widely reported in the literature2,4,5,28,45, but the reasons for this prevalence remain controversial. Factors such as increased sensitivity to pain, the increased preva-lence of emotional stress, anxiety, or depression, physiological differences (hormonal differences), differences in muscular structure, and increased preoccupation and treatment seeking1,9,41 in fe-males have all been proposed. Conversely, studies on children have not shown significant differ-ences between genders for the signs and symp-toms of TMD14,34, reinforcing the possible role of hormones in the development of this disorders, considering that these studies were conducted on prepubescent children who were therefore not influenced by reproductive hormones14.

The report of parafunctional habits was sta-tistically associated with the presence of TMD symptoms and the “treatment need” (DMF in-dex). In addition, the habits of clenching teeth, chewing gum, resting chin on hand, biting the tongue, biting lips, lateral sleep position, and chewing ice/lollipops were associated with the presence of this disorder symptoms (DMF in-dex). Similar to this results, several studies have shown a positive association between parafunc-tional habits and the presence of signs and symp-toms of TMD4,18,45,46. Other studies, however, have contested this association34,47,48. The results of this study suggest that parafunctional habits may be important associated factors to TMD occurrence and progression, but further examination, relat-ing each habit to specific diagnosis of this dys-function is necessary for better understanding of their participation in the etiology of the different subgroups of TMD. It is noteworthy that, in the present study, bruxism and clenching habits were self-reported by the students2,4,16,34. This type of evaluation carries a limitation that is inherent in it: its natural subjectivity, considering that most of the deleterious habits are unconscious, which means that the patient is not always aware of their presence. This factors can cause risks of over or underestimate the real prevalence of this condition49. The literature considers the poly-somnography exam as the “gold standard” for the diagnose of sleep bruxism and clenching, howev-er is a suitable technique only for small samples due to high cost and limited availability49, which compromises its use in larger samples studies, as the present one.

Paulino MR emotional stress (82.5%) and anxiety (40.3%).

Depression was present in 10.6% of the sample. These results are in agreement with previous studies which have also demonstrated elevated prevalence of emotional factors in this

popula-tion24,26,32,33. Guhur et al.26 assert that the moment

of college entrance examination usually coincides with the turbulent period of life that is adoles-cence, and the professional decision usually gen-erates anxiety. In addition, factors such as family interference, social pressure and the absence of a realistic view about certain areas of knowledge or professions may contribute to elevate the emo-tional tension and anxiety26,32,33. The low prev-alence of depression reflects the greater role of tension and stress events in the evaluated sample, as demonstrated in previous studies24,26,32,33. It is noteworthy that in this study the evaluation of the presence of emotional stress was determined from an objective question related to their pres-ence/absence directed to volunteers. This data should be analyzed with caution, since that emo-tional tension is subjective by nature. This type of evaluation was choosen due to the absence of more specific and precise instruments to evaluate this emotional component.

Several studies have shown a significant as-sociation between different emotional factors and the presence of signs and symptoms of

TMD9,11,13,14. In this study, the report of

emotion-al stress was statisticemotion-ally associated with the pres-ence of TMD symptoms and the need for treat-ment (DMF index). These findings were con-sistent with other studies performed in various populations17,28. It is believed that stress can af-fect biological processes related to the transmis-sion and perception of pain, promoting chronic muscular hyperactivity, which in turn can dam-age the TMJ and related structures, in addition to contributing to the creation and evolution of parafunctional habits8,50.

Several studies have also shown a signifi-cant correlation between anxiety and depres-sion and the presence of signs and symptoms of

TMD11,12,15,28,29. Corroborating these results, data

showed that anxiety was statistically associated with the presence of TMD signs and symptoms (DMF index or simplified clinical examination) and the need for treatment (DMF index). Simi-larly, Karibe et al.45 showed a significant correla-tion between anxiety and the presence of TMD symptoms in a population of Japanese children and adolescents.

The depression results showed a significant correlation only with the “treatment need”.

Ac-cording to Fonseca et al.33, patients who are need-ing treatment represents an increased severity of TMD symptoms, making therapeutic interven-tion necessary. This result may suggest that de-pression plays a significant role in the progression and severity of this disorder, corroborating sev-eral studies in the literature10,12,15,28,29,50. However, in light of the limitations of this study design, it is difficult to determine whether depression was responsible for the development of more severe TMD or whether it is caused by the symptoms of the disorder.

When we analyzed the QL data, we observed that volunteers with the signs and symptoms of TMD (DMF index or simplified clinical ex-amination protocol) presented higher OHIP-14 scores than volunteers without signs and symp-toms, suggesting that this disorder negatively impacts the OHRQL. These results are consistent with several other studies that showed signifi-cantly higher OHIP-14 scores in patients with TMD than in asymptomatic individuals19,21,23.

The DMF index data showed that volunteers needing treatment had higher OHIP-14 scores than patients who did not need treatment; fur-thermore, as the severity of TMD signs and symptoms increased (determined by reported symptoms), greater was the impact on OHRQL, which is consistent with previous studies21-23. A study performed on university students showed that the main complaint by volunteers with se-vere TMD is pain, which plays a significant role in psychosocial behavior and QL23. A recent sys-tematic review also showed strong evidence that pain negatively impacts OHRQL in TMD pa-tients22.

When results from the simplified clinical ex-amination protocol were evaluated, volunteers with a clinical sign of TMD had OHIP-14 scores that were statistically higher than those of patients without clinical signs, with the highest scores be-longing to the group with signs of both articular and muscular TMD, followed by the group with signs of muscular TMD. These data support the claim that individuals with both articular and muscular signs presented an increased severity of TMD23 and thus have a more severely impacted

QL21,22,51. The higher OHIP-14 scores in the group

with signs of muscular TMD is supported by the clinical observation that these individuals had more painful symptoms than individuals with clinical signs of articular TMD19,22,51.

e C

ole

tiv

a,

23(1):173-186,

2018

TMD. Similarly, several studies have also shown an increased harm in the physical pain domain in several populations, reinforcing the role of pain in the QL of individuals with TMD21-23,51.

The data in this study presented a high preva-lence of TMD signs and symptoms in college pre-paratory students, with a large portion in need of treatment. In addition, the negative impact of this disorder on OHRQL was evident. Among the associated factors, female gender, parafunc-tion, and anxiety played a great role. These data indicate the need teachers and students being in-formed about TMDs signs and symptons and its possible link to parafunctional habits and emo-tional factors to improve early detection and to prevent the problem, which directly affects prog-nosis and the efficacy of treatment.

The elevated prevalence of self-reported emotional stress and anxiety, observed in this study reinforces the evidence of great emotional burden of which the college preparatory students are submitted, and these were statistically associ-ated with the presence of signs and symptoms of TMD, which can suggest that this population is submitted to important risk factors for the devel-opment and progression of this disorder. Guhur et al.26 states that there is a necessity for

vocation-al guidance service and psychologicvocation-al counsel-ing to adolescents in schools, so that they can go through this period of difficult choices. Finally, it is also suggested to include other health pro-fessionals in these services such as dentists and physicians, allowing the early diagnose and man-agement of conditions that can be aggravated or initiated during this period, as TMD.

In addition, these data, in addition to nu-merous other studies, which have shown high prevalence of TMD in different age

rang-es3,7,9,12,15,21,23,27,30, suggests the need for

“Temporo-mandibular Dysfunction and Orofacial Pain” services into the public health service, especially into the Centro de Especialidades Odontológicas – CEO (Centers of Dental Specialists). Treatment centers for TMD patients financially supported by the Sistema Único de Sáude (Brazilian Na-tional Health System) are scarse, and generally restricted to training centers and/or research stitutions (universities or dental schools). The in-clusion of this knowledge area may improve the access to comprehensive dental care to a larger portion of the population that suffers from the signs and symptoms of this disorder, preventing more severe complications and improving their quality of life.

Collaborations

Paulino MR Referemces

1. De Leeuw R. Dor orofacial: guia de avaliação, diagnós-tico e tratamento. 4ª ed. São Paulo: Quintessence; 2010. 2. Gavish A, Halachmi M, Winocur E, Gazit E. Oral habits

and their association with signs and symptoms of tem-poromandibular disorders in adolescent girls. J Oral Rehabil 2000; 27(1):22-32.

3. Santos ECA, Bertoz FA, Pignatta LMB, Arantes FM. Avaliação clínica de sinais e sintomas da disfunção temporomandibular em crianças. Rev Dent Press Orto-don Ortop Facial 2006; 11(2):29-34.

4. Winocur E, Littnerusb D, Adamsusb I, Gavish A. Oral habits and their association with signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in adolescents: a gen-der comparison. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2006; 102(4):482-487.

5. Gonçalves DA, Dal Fabbro AL, Campos JA, Bigal ME, Speciali JG. Symptoms of Temporomandibular Dis-orders in the Population: An Epidemiological Study. J Orofac Pain 2010; 24(3):270-278.

6. Hilgenberg PB, Saldanha AD, Cunha CO, Rubo JH, Conti PC. Temporomandibular disorders, otologic symptoms and depression levels in tinnitus patients. J Oral Rehabil 2012; 39(4):239-244.

7. Thilander B, Rubio G, Pena L, Mayorga C. Prevalence of Temporomandibular Dysfunction and Its Associa-tion With Malocclusion in Children and Adolescents: An Epidemiologic Study Related to Specified Stages of Dental Development. Angle Orthod 2002; 72(2):146-154.

8. Gameiro GH1, Silva Andrade A, Nouer DF, Ferraz de Arruda Veiga MC. How may stressful experiences con-tribute to the development of temporomandibular dis-orders? Clin Oral Investig 2006; 10(4):261-268. 9. Monteiro DR, Zuim PRJ, Pesqueira AA, Ribeiro PP,

Garcia AR. Relationship between anxiety and chronic orofacial pain of Temporomandibular Disorder in a group of university students. J Prosthodont Res 2011; 55(3):154-158.

10. McMillan AS, Wong MCM, Lee LTK, Yeun RWK. De-pression and diffuse physical symptoms in Southern Chinese with Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Rehabil 2009; 36(6):403-407.

11. Giannakopoulos NN, Keller L, Rammelsberg P, Kro-nmüller KT, Schmitter M.Anxiety and depression in patients with chronic temporomandibular pain and in controls. J Dent 2010; 38(5):369-376.

12. Fernandes G, Gonçalves DA, De Siqueira JT, Camparis CM. Painful temporomandibular disorders, self re-ported tinnitus, and depression are highly associated.

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2013; 71(12):943-947.

13. Mottaghi A, Razavi SM, Elham Zamani Pozveh E, Ja-hangirmoghaddam M. Assessment of the relationship between stress and temporomandibular joint disorder in female students before university entrance exam (Konkour exam). Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2011; 8(Supl. 1):76-79.

14. Pizolato RA, Freitas-Fernandes FS, Gavião MB. Anx-iety/depression and orofacial myofacial disorders as factors associated with TMD in children. Braz Oral Res

2013; 27(2):156-162. Acknowledgments

e C

ole

tiv

a,

23(1):173-186,

2018

15. Calixtre LB, Grüninger BLS, Chaves TC, Oliveira AB. Is there an association between anxiety/depression and Temporomandibular Disorders in college students? J Appl Oral Sci 2014; 22(1):15-21.

16. Winocur E, Gavish A, Finkelshtein T, Halachmi M, Gazit E. Oral habits among adolescent girls and their association with symptoms of temporomandibulardis-orders. J Oral Rehabil 2001; 28(7):624-629.

17. Carvalho LPM, Piva MR, Santos TS, Ribeiro CF, Araú-jo CRF, Souza LB. Estadiamento clínico da disfunção temporomandibular: estudo de 30 casos. Odontol Clín-Cient 2008; 7(1):47-52.

18. Medeiros SP, Batista AUD, Forte FDS. Prevalência de sintomas de disfunção temporomandibular e hábitos parafuncionais em estudantes universitários. RGO

2011; 59(2):201-208.

19. John MT, Reissmann DR, Schierz O, Wassell RW. Oral health-related quality of life in patients with temporo-mandibular disorders. J Orofac Pain 2007; 21(1):46-54. 20. Barros VM M, Seraidarian PI, Côrtes MI, Paula LV. The impact of orofacial pain on the quality of life of pa-tients with temporomandibular disorder. J Orofac Pain

2009; 23(1):28-37.

21. Schierz O, John MT, Reissmann DR, Mehrstedt M, Sz-entpétery A. Comparison of perceived oral health in patients with temporomandibular disorders and dental anxiety using oral health-related quality of life profiles.

Qual Life Res 2008; 17(6):857-866.

22. Dahlström L, Carlsson GE. Temporomandibular disor-ders and oral health-related quality of life. A systematic review. Acta Odontol Scand 2010; 68(2):80-85. 23. Lemos GA, Paulino MR, Forte FDS, Beltrão RTS,

Ba-tista AUD. Influence of temporomandibular disorder presence and severity on oral health-related quality of life. Rev Dor 2015; 16(1):10-14.

24. Godoy F, Rosenblatt A, Godoy-Bezerra J. Temporo-mandibular Disorders and Associated Factors in Bra-zilian Teenagers: A Cross-Sectional Study. Int J Prostho-dont 2007; 20(6):599-604.

25. Melo GM, Barbosa JFS. Parafunção × DTM: a influ-ência dos hábitos parafuncionais na etiologia das de-sordens temporomandibulares. POS 2009; 1(1):43-48. 26. Guhur MLP, Alberto RN, Carniatto N. Influências

bio-lógicas, psicológicas e sociais do vestibular na adoles-cência. Roteiro 2010; 35(1):115-138.

27. Sena MF, Mesquita KS, Santos FR, Silva FW, Serrano KV. Prevalence of temporomandibular dysfunction in children and adolescents. Rev Paul Pediatr 2013; 31(4):538-545.

28. Minghelli B, Morgado M, Caro T. Association of tem-poromandibular disorder symptoms with anxiety and depression in Portuguese college students. J Oral Sci

2014; 56(2):127-133.

29. Selaimen C, Brilhante DP, Grossi ML, Grossi PK. Ava-liação da depressão e de testes neuropsicológicos em pacientes com desordens temporomandibulares. Cien Saude Colet 2007; 12(6):1629-1639.

30. Schmitter M, Rammelsberg P, Hassel A. The preva-lence of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorders in very old subjects. J Oral Rehabil 2005; 32(7):467-473.

31. Peruzzo AS, Cattani BC, Guimarães ER, Boechat LC, Argimon IIL, Scarparo HBK. Estresse e vestibular como Desencadeadores de somatizações Em adolescentes e adultos jovens. Psicol Argum 2008; 26(55):319-327. 32. Soares AB. Ansiedade dos estudantes diante da

expec-tativa do exame vestibular. Paideia 2010; 20(45):57-62. 33. Fonseca DM, Bonfante G, Valle A, Freitas SFT. Diag-nóstico pela Anamnese da Disfunção Craniomandibu-lar. RGO 1994; 42(1):23-28.

34. Emodi-Perlman A, Eli I, Friedman-Rubin P, Goldsmith C, Reiter S, Winocur E. Bruxism, oral parafunctions, anamnestic and clinical findings of temporoman-dibular disorders in children. J Oral Rehabil 2012; 39(2):126-135.

35. Lemos GA, Moreira VG, Forte FDS, Beltrão RTS, Ba-tista AUD. Correlação entre sinais e sintomas da Dis-função Temporomandibular (DTM) e severidade da má oclusão. Rev Odontol UNESP 2015; 44(3):175-180. 36. Botega NJ, Bio MR, Zomignani MA, Garcia-Júnior C,

Pereira WAB. Transtornos do humor em enfermaria de clínica médica e validação de Escala de Medida (HAD) de Ansiedade e Depressão. Rev Saude Publica 1995; 29(5):355-363.

37. Soe KK, Gelbier S, Robinson PG. Reliability and valid-ity of two oral health related qualvalid-ity of life measures in Myanmar adolescents. Community Dent Health 2004; 21(4):306-311.

38. Oliveira BH, Nadanovsky P. Psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Oral Health Impact Pro-file-short form. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2005; 33(4):307-314.

39. Chaves TC, Oliveira AS, Grossi DB. Principais instru-mentos para avaliação da disfunção temporomandibu-lar, parte I: índices e questionários; uma contribuição para a prática clínica e de pesquisa. Fisioter pesqui 2008; 15(1):92-100.

40. Campos JADB, Gonçalves DAG, Camparis CM, Specia-li JG. ConfiabiSpecia-lidade de um formulário para diagnósti-co da severidade da disfunção temporomandibular. Rev Bras Fisioter 2009; 13(1):38-43.

41. Pedroni CR, De Oliveira AS, Guaratini MI. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders in university students. J Oral Rehabil 2003; 30(3):283-289.

42. Oliveira AS, Dias EM, Contato RG, Berzin F. Prevalence study of signs and symptoms of temporomandibular disorder in Brazilian college students. Braz Oral Res

2006; 20(1):3-7.

43. Bonjardim LR, Lopes-Filho RJ, Amado G, Albuquer-que-Júnior ALC, Gonçalves SRJ. Association between symptoms of Temporomandibular Disorders and gen-der, morphological occlusion and psychological factors in a group of university students. Indian J Dent Res

2009; 20(2):190-194.

Paulino MR 45. Karibe H, Shimazu K, Okamoto A, Kawakami T, Kato Y, Warita-Naoi S. Prevalence and association of self-re-ported anxiety, pain, and oral parafunctional habits with temporomandibular disorders in Japanese chil-dren and adolescents: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Oral Health 2015; 15:8.

46. Michelotti A, Cioffi I, Festa P, Scala G, Farella M. Oral parafunctions as risk factors for diagnostic TMD sub-groups. J Oral Rehabil 2010; 37(3):157-162.

47. Cheifetz AT, Osganian SK, Allred EN, Needleman HL. Prevalence of bruxism and associated correlates in chil-dren as reported by parents. J Dent Child (Chic) 2005; 72(2):67-73.

48. Merighi LBM, Silva MMA, Ferreira AT, Genaro KF, Berretin-Felix G. Ocorrência de disfunção temporo-mandibular (DTM) e sua relação com hábitos orais deletérios em crianças do município de Monte Negro – RO. Rev CEFAC 2007; 9(4):497-503.

49. Lobbezoo F, Ahlberg J, Glaros AG, Kato T, Koyano K, Lavigne GJ, de Leeuw R, Manfredini D, Svensson P, Wi-nocur E. Bruxism defined and graded: an international consensus. J Oral Rehabil 2013; 40(1):2-4.

50. Minghelli B, Kiselova L, Pereira C. Associação entre os sintomas da disfunção temporo-mandibular com fac-tores psicológicos e alterações na coluna cervical em alunos da Escola Superior de Saúde Jean Piaget do Al-garve. Rev Port Sau Pub 2011; 29(2):140-147.

51. Reissmann DR, John MT, Schierz O, Wassell RW. Functional and psychosocial impact related to specific temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. J Dent 2007; 35(8):643-650.

Article submitted 30/05/2015 Approved 24/11/2015