junho de 2016

Juliana Andreia Oliveira Martins

Systematic review of school engagement

in elementary school: interveners and

outcomes

Escola de Psicologia

Sys

tematic re

vie

w of school engagement in element

ar y school: inter vener s and outcomes Juliana Andr eia Oliv eir a Mar tins UMinho|20 16

Dissertação de Mestrado

Mestrado em Psicologia Aplicada

Trabalho realizado sob a orientação do

Professor Doutor Pedro José Sales Luís Fonseca Rosário

e coorientação da

Professora Doutora Paula Cristina Soares Magalhães

Silva Correia

junho de 2016

Juliana Andreia Oliveira Martins

Systematic review of school engagement

in elementary school: interveners and

outcomes

Nome: Juliana Andreia Oliveira Martins

Endereço eletrónico: pg28210@alunos.uminho.pt

Número do Cartão de Cidadão: 14140657

Título da dissertação: Systematic review of school engagement in elementary school: interveners and outcomes.

Orientador: Professor Doutor Pedro José Sales Luís Fonseca Rosário

Coorientador: Professora Doutora Paula Cristina Soares Magalhães Silva Correia

Ano de conclusão: 2016

Designação do Mestrado: Mestrado em Psicologia Aplicada

É AUTORIZADA A REPRODUÇÃO INTEGRAL DESTA DISSERTAÇÃO APENAS PARA EFEITOS DE INVESTIGAÇÃO, MEDIANTE DECLARAÇÃO ESCRITA DO INTERESSADO, QUE A TAL SE COMPROMETE.

Universidade do Minho, 13/06/2016

ii

INDEX

RESUMO ... iv ABSTRACT ... v Introduction ... 6 Method ... 8 Search strategy ... 8 Selection criteria ... 8 Data extraction ... 9 Results ... 11 Main results ... 11School engagement and academic achievement. ... 11

The role of class peers, teachers, or parents on school engagement ... 12

Class peers. ... 12

Teachers. ... 13

Parents. ... 14

Impact of interventions on school engagement. ... 14

Discussion ... 22

Limitations and future research directions ... 25

Conclusions ... 25

References ... 26

INDEX FOR TABLES Table 1. Article search terms and databases searched ... 8

Table 2. Summary of studies included in this review ... 16

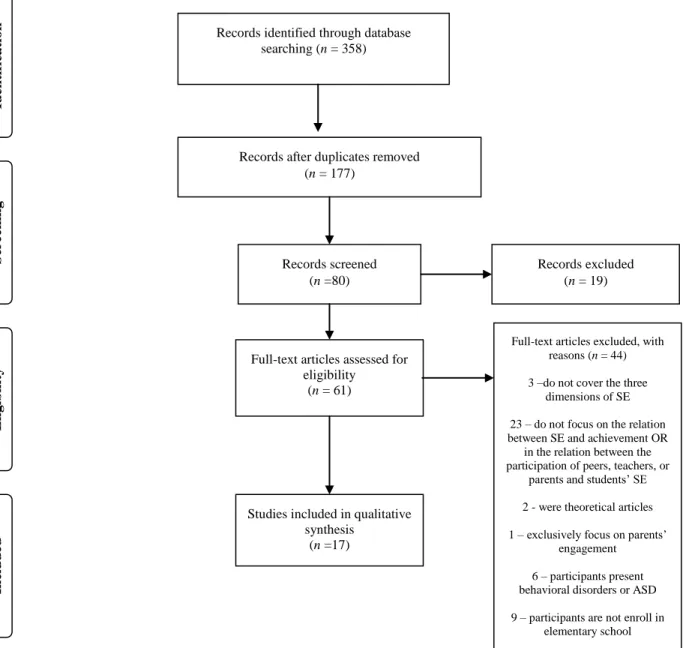

INDEX FOR FIGURES Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram: Flow of information through the search and selection process during this systematic review. ... 10

iii

AGRADECIMENTOS

“Si se cree y se trabaja, se puede.” Diego Pablo Simeone

Gostaria de agradecer ao meu orientador, Professor Doutor Pedro Rosário pela sua competência e dedicação e por todos os ensinamentos que largamente contribuíram para o meu progresso e aprendizagem.

Agradeço também à minha coorientadora, Professora Doutora Paula Magalhães pelos momentos de partilha de conhecimento e, sobretudo, pela confiança e incentivo.

Ao GUIA, pela arte de muito bem receber e por ser um exemplo vivo daquilo que representa uma verdadeira equipa.

A toda a minha família e amigos, o meu agradecimento mais sentido, nomeadamente: Aos meus pais, os meus verdadeiros alicerces, pelo amor incondicional, por estarem sempre presentes, sobretudo, nas horas mais difíceis, pelo apoio e por acreditarem em mim, mesmo quando eu duvidei.

À minha irmã Marinha, companheira de uma vida e melhor amiga, pela paciência, por me incentivar a querer ser sempre melhor e por celebrar comigo todos os triunfos. Este é mais um!

Ao Marco, o mais recente membro da família, pelos momentos de descontração, desabafos e risadas.

Ao Ângelo, pelos abraços e pela alegria dos momentos parvos que me proporciona todos os dias.

Às Maravilhas por todas as experiências partilhadas, e por todos os momentos de estudo, companheirismo, carinho e gargalhadas.

Ao Miguel, o meu melhor amigo, por estar sempre do meu lado mesmo nas ocasiões mais improváveis e por ter a capacidade de me devolver um sorriso na hora certa.

Ao Rui, por ser o meu maior cúmplice e por me saber fazer rir nos momentos mais angustiantes. Obrigada por todos os mimos, por compreenderes as minhas ausências e por acreditares sempre que eu seria capaz!

iv

Revisão sistemática sobre o school engagement no ensino básico: intervenientes e resultados

RESUMO

O baixo comprometimento com as atividades escolares pode trazer graves consequências aos estudantes, como o envolvimento em comportamentos disruptivos, perda de interesse no estudo, baixo rendimento e um risco acrescido de abandono escolar. A pesquisa existente menciona a existência de uma relação estreita entre school engagement e rendimento académico no ensino secundário, estando ainda em falta revisões sistemáticas com foco no ensino básico. O presente estudo tem como objetivo compreender a relação entre school engagement e rendimento escolar e o papel desempenhado pelo apoio dos pares, pais ou professores no school engagement de estudantes do primeiro ciclo. Foi realizada uma pesquisa sistemática de artigos publicados entre janeiro e novembro de 2015 em três bases de dados (Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC). A pesquisa foi realizada de acordo com as recomendações do PRISMA e da Cochrane. Os resultados apontam para uma relação entre school engagement e rendimento académico e realçam a eficácia das intervenções desenhadas para promover o school engagement no ensino básico. Adicionalmente, o apoio dos pares e professores influencia o school engagement, permanecendo menos explorado o efeito do suporte parental. Assim, é necessária mais investigação que explore a relação entre school engagement e suporte parental.

Palavras-chave: school engagement, rendimento académico, elementary students, revisão sistemática.

v

Systematic review of school engagement in elementary school: interveners and outcomes

ABSTRACT

Low engagement in school activities could have serious consequences for students, such as involvement in disruptive behaviors, loss of interest in studying, low achievement, and an increased risk of early school leaving. Extant research reports a close relationship between school engagement and academic achievement in high school, yet systematic reviews focusing on elementary school are still missing. The present study aims to examine the relationships between school engagement and school achievement, and the role played by peers, teachers, or parents’ support on elementary students’ school engagement. A systematic search of original articles published between January 1, 2005 and November 1, 2015 was conducted in three databases (Web of Science, Scopus, ERIC). The research followed PRISMA statement and Cochrane’s guidelines. Findings show a relationship between school engagement and academic achievement and stress the effectiveness of the interventions designed to promote school engagement in elementary school. Additionally, peers’ and teachers’ support showed an impact on elementary students’ school engagement, but evidence on the effect of parents’ support is still limited. Further research is needed to explore the role of parental support on school engagement.

Keywords: school engagement, academic achievement, elementary students, systematic review.

6 Systematic review of school engagement in elementary school: interveners and outcomes

Introduction

The seminal paper by Mosher and McGowan (1985) launched the academic interest in school engagement (SE) and, since then, SE has been receiving increased attention by both researchers and teachers (Christenson & Reschly, 2012). The concept of SE emerged in the school context and is considered the most appropriate and best-suited model for

understanding school completion and dropout (Christenson et al., 2008;Finn, 2006;Virtanen, Lerkkanen, Poikkeus, & Kuorelahti, 2014).

The most common definition of SE is by Fredricks, Blumenfeld, and Paris (2004), who coined SE as a multidimensional and multifaceted construct subsuming aspects of students’ behavior, emotion, and cognition. These three aspects of SE, also called dimensions, are dynamically interrelated (Wang & Holcombe, 2010). Behavioral

engagement refers to the participation and involvement of students in academic, social, and extracurricular activities. It includes three forms of engagement: “positive conduct” (e.g., attending class, following class rules), “involvement in learning” (e.g., making an effort, being persistent, asking questions, finishing homework), and “participation in school-related activities” (e.g., taking part in extracurricular activities such as sports teams) (Fredricks et al., 2004). Emotional engagement concerns students’ affective reactions and sense of

connectedness with school (Wang, Willett, & Eccles, 2011). Finally, cognitive engagement requires personal investment in academic tasks, self-regulation, and value of the learning process (Fredricks et al., 2004).

Literature reports that a high percentage of students are disengaged from school (e.g., Lee, 2014; Wang & Fredricks, 2013). This worrying scenario may help to explain why the research on SE has been, and still is, driven by the goal of improving students’ learning, personal development (Buijs & Admiraal, 2013; Hagger et al., 2015), and school

achievement (Finn & Zimmer, 2012; Rosário et al., 2015). In fact, SE is considered the cornerstone of students’ learning and a strong protective factor that prevents school dropout and promotes student retention (Wang & Fredricks, 2013). This proposition is further

sustained by teachers who argue that many students are not committed to learning, displaying minimal effort towards school activities (Rosário et al., 2013), while others feel alienated from school (Buijs & Admiraal, 2013; Wang et al., 2011). This educational scenario is of

7 growing concern for educators, as disengaged students are likely to struggle academically

(Rosário et al., 2015), display problematic behaviors (Fredricks, et al., 2004), have negative psychosocial outcomes (Li & Lerner, 2011), and experience academic failure (Wang & Fredricks, 2013). Literature also shows that high levels of SE are positively associated with desired academic, social, and emotional learning outcomes (Klem & Connell, 2004), and negatively associated with student unrest, such as depressive symptoms and burnout (Upadyaya & Salmela-Aro, 2013).

Acknowledging that a vast number of students are disengaged from school (e.g., Buijs & Admiraal, 2013; Lee, 2014; OECD, 2012), SE has been studied in different educational levels, with different purposes and through different perspectives. In particular, SE has been widely studied with college students (e.g.,Heng, 2014; Horstmanshof & Zimitat, 2007; Wyatt, 2011), and findings show a positive relationship between SE and students’ achievement (Handelsman et al., 2010). Still, research on SE in high school has been

receiving less attention from researchers (e.g. Handelsman, et al., 2010; Skinner & Belmont, 1993). The explanation could be related to the idea that high school students’ lack of interest towards school and school activities might be an extension of the behavioral patterns

displayed throughout elementary and middle school (Alexander, Entwisle, & Kabbani, 2001; Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011). This proposition is reinforced by SE literature reporting a close relationship between SE during elementary and middle school (e.g., Gottfried, Marcoulides, Gottfried, Oliver, & Guerin, 2007; Skinner, Zimmer-Gembeck, & Connell, 1998). All things considered, to maximize the positive effects of SE (e.g., Núñez et al., 2013; Rosário et al., 2015), literature suggest the need to conduct interventions focused on the promotion of SE as early as possible (i.e. elementary and middle school), and prior to the emergence of the typical adolescent behaviors (e.g., high investment in relationships with peers and in activities like sports, arts, and music, in detriment of school-related activities) (Mahatmya, Lohman, Matjasko, & Farb, 2012). Yet, an organized road map on the investigations conducted on SE in elementary school is still lacking.

In sum, due to the importance of SE during elementary school years, and of its role in later development (Hirschfield & Gasper, 2011), the current review seeks to map the

relationships between SE and academic achievement in elementary school, as well as the role played by class peers, teachers, and parents’ participation in the SE of elementary students.

8 Findings are expected to deepen the understanding of SE in elementary school and to suggest future directions for research. We examined the research conducted on relationships between SE and school achievement, and also the role played by peers, teachers, or parents’ support in students’ SE, in the last 10 years.

Method

The present systematic review conforms to the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines (see Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Intervention, Higgins & Green, 2011) for the search, selection, and data extraction. Data abstraction and elaboration of the manuscript followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis: The PRISMA Statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman; The PRISMA Group, 2009) guidelines.

Search strategy

The papers included in this review were obtained through a systematic search carried out in November 2015, in ERIC, Scopus, and Web of Science databases by JM. The keywords used for the search were: “school engagement” OR “academic engagement” AND

“elementary school” OR “elementary students” OR “elementary grades” (see Table 1).

Table 1

Article search terms and databases searched

Academic-engagement related

search terms Academic-level search terms Databases School engagement Elementary school ERIC Academic engagement Elementary students Scopus

Elementary grades Web of Science

Selection criteria

To deepen our understanding of SE in elementary school, particularly investigating the relationships between SE and academic achievement and the role played by peers, teachers, and parents on SE, inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined as required by the Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, 2001). Therefore, in the identification and screening phases,

9 articles were included when abstracts met the selection criteria or when the first author had doubts regarding the fulfilment of the selection criteria. Hence, to be included, papers should: i) have been published between 2005 and 2015; ii) present original research data; iii) have a sample of children aged between 5 and 12 (elementary school years); iv) include data about evaluations, or interventions, related to the promotion of academic or SE for improving academic achievement, OR include data about the relation between the participation of peers, teachers, or parents and students’ SE; v) cover the three dimensions of SE or focus on AE; and vi) be written in Portuguese, Spanish or English.

Conversely, papers were excluded when they did not fulfil the above criteria or when they exclusively focused on academic variables instead of focusing on SE. Meta-analysis were excluded, as well as studies focusing on reading engagement, reading frequency, and reading comprehension. Additionally, studies exclusively focused on teacher’s engagement or parent’s engagement were not included. Besides, studies featuring children with behavioral disorders such as inattention, hyperactivity, or aggressive behavior, or with a diagnoses such as Autism Spectrum Disorder or Emotional and Behavioral Disabilities were also excluded. Finally, theoretical manuscripts were not included in the review. The inclusion process is summarized in Figure 1 using a PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Data extraction

Titles and abstracts of potentially relevant articles were sorted by JM in the

identification and screening phases. Thereafter, in the eligibility phase, all full-text articles were independently examined, and assessed, by two reviewers (JM and SL) to ensure that they met the inclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers (JM and SL), and a consensus was obtained for all included articles.

For each article, the following information was then collected: reference and country where the study was conducted, a brief summary of the purposes, sample size, age and school year of the sample, and main results (Table 2). Table 2 was independently reviewed by a third researcher (PM).

10

Records identified through database searching (n = 358) Scre ening Inclu ded E lig ibi lit y Identif ica tio n

Records after duplicates removed (n = 177)

Records screened (n =80)

Records excluded (n = 19)

Full-text articles assessed for eligibility

(n = 61)

Full-text articles excluded, with reasons (n = 44) 3 –do not cover the three

dimensions of SE 23 – do not focus on the relation between SE and achievement OR

in the relation between the participation of peers, teachers, or

parents and students’ SE 2 - were theoretical articles 1 – exclusively focus on parents’

engagement 6 – participants present behavioral disorders or ASD 9 – participants are not enroll in

elementary school

Studies included in qualitative synthesis

(n =17)

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram: Flow of information through the search and selection process during this systematic review.

11

Results

With the database search, a total of 358 articles were identified (90 from Web of Science, 53 from Scopus, and 215 from ERIC). After deletion of the duplicates (n=181) and removal of papers after screening by title (n=97), and abstract (n=19), 61 articles remained as potentially relevant. The full texts of the 61 studies selected were retrieved and analyzed to obtain the final selection. Altogether, 17 articles fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the present systematic review.The complete selection process is summarized in the flow diagram (Figure 1) in agreement with the PRISMA Statement (Moher et al., 2009). An overview of the included studies is summarized in Table 2.

Main results

Data was organized by grouping papers according to the three main topics that

emerged: (i) SE and academic achievement; (ii) the role of class peers, teachers, or parents on SE; and (iii) impact of interventions on SE. Each section summarizes the main conclusions of each topic.

Considering that different authors present different terms to describe similar

constructs (e.g., SE and academic engagement), we decided to be consistent with the terms used in the articles included in our sample (i.e. terms were kept as originally described).

School engagement and academic achievement. Of the 17 studies comprising the

present systematic review, the 6 included in this topic (Galla et al., 2014; Hughes, Luo, Kwok, & Loyd, 2008; Hughes & Zhang, 2007; Iyer, Kochenderfer-Ladd, Eisenberg, & Thompson, 2010; Moller, Stearns, Mickelson, Bottia, & Banerjee, 2014;Portilla, Ballard, Adler, & Obradovic, 2014) examined the relation between SE and academic achievement. Both the studies by Galla and colleagues (2014) and Moller and colleagues (2014), show that the level of engagement is related to achievement, and indicated academic engagement (AE) as a strong predictor of mathematics achievement in elementary school (first to fifth grade). Moreover, Hughes and Zhang (2007) found a positive relationship between reading achievement and SE. Additionally, a study by Hughes and colleagues (2008) highlights the key role of AE on achievement, on both mathematics and reading domains. In general, research points SE as a significant predictor of academic achievement (Iyer, et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2008) and, therefore, positively related to academic competence (Portilla et al., 2014). These associations

12 between SE and achievement were further substantiated by the findings from Hughes and

Zhang (2007), who reported that students with low reading performance, and low mathematics achievement, were perceived by their teachers as not very engaged with school. Still, despite literature indicating that higher levels of SE is associated with higher levels of academic achievement (Iyer et al., 2010), findings by Moller and colleagues (2014) show that SE, by itself, may not be sufficient to improve mathematics achievement.

The role of class peers, teachers, or parents on school engagement. Ten of the 17

studies focused on the role of class peers or teachers on SE (Buhs, Ladd, & Heral, 2006; Chen, Hughes, Liew, & Kwok, 2010; Hoglund, Klingle, & Hosan, 2015; Hughes, Dyer, Luo, & Kwok, 2009; Hughes et al., 2008; Iyer et al., 2010; Hughes & Zhang, 2007; Lynch, Lerner, & Leventhal, 2012; Portilla et al., 2014; Rimm-Kaufman, Larsen, Baroody, Curby, & Abry, 2015).

Class peers. The results stress that peer culture, i.e. school-wide peer behaviors and

nature of peerrelationships in school, is associated with individual achievement and SE, with levels of SE increasing as peer culture becomes more positive (e.g., high levels of friendship quality, students care) (Lynch et al., 2012). This proposition highlights the role that

relationships between students and their peers may play in SE. Peer victimization (i.e. frequent verbal harassment, physical abuse, or exclusionary behaviors), for example, is related to the development of negative attitudes towards school, including disengagement from school activities and poor academic outcomes (Iyer et al., 2010). This assertion is supported by Iyer and colleagues (2010), and Buhs and colleagues (2006) who found that higher levels of peer victimization, or peer exclusion, were associated with lower levels of academic achievement, this effect being mediated by low levels of SE. This means that students who were exposed to peer victimization were likely to display low levels of SE, and, consequently, low academic achievement (Iyer et al., 2010). Besides, early peer rejection was associated with declines in classroom participation and increases in school avoidance. In other words, children

chronically victimized are more likely to exhibit a decrease in SE (Buhs et al., 2006). These findings may be explained by the lack of social competencies exhibited by victimized children, which might prevent their engagement in, and concentration on, school tasks.

Moreover, literature focused on the role played by children peer relationships on academic achievement (see Lynch et al., 2012) and analyzed the relationships between a set of

13 variables such as,peer acceptance/rejection and SE and achievement (e.g., Buhs et al., 2006), and peer academic reputation and AE and achievement (Chen et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009). Still, literature analyzing the effect of being perceived by classmates as academic competent on academic achievement has received little attention by researchers. Findings of the latter indicated that the effect of peer academic reputation (i.e. students reputation within a peer group regarding academic competence) on subsequent engagement was partially

mediated by students perceived academic competence (Chen et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009). In general, these studies reported that peer academic reputation influences students’

perceptions about their academic competences, and this influential process is likely to display motivational efforts which, subsequently, may affect academic achievement. Additionally, Chen and colleagues (2010) suggested that peer academic reputation may also indirectly affect AE. Students with high and low peer academic reputation are likely to be offered differential learning opportunities in class. For example, students with low peer academic reputation may have less opportunities to work with high achieving students and be enrolled in challenging classroom activities than their counterparts, which is likely to affect their SE. All things considered, data warns for the possibility of peer academic reputation influencing the individual levels of AE and achievement (Chen et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009).

Furthermore, Hughes and Zhang (2007) investigated the structure of peers’

perceptions of classmates’ academic competencies on classroom engagement in elementary schools. Namely, authors studied the effects of classroom indegree for ability (the degree to which peer nominations as academically competent show consensus and focus on a few number of students) on several variables, among which was classroom engagement. Findings indicated that students with low achievement (e.g., low reading ability) were less engaged in classes in which students’ perceptions of peers as academically less capable were more centralized (i.e. consensual and focused on a small number of students), than in classes in which students’ perceptions of peers as academically less capable were less centralized. Overall, data indicates that students’ perceptions of their peers’ competence have a real impact in academic life, with a direct influence on peer acceptance and SE.

Teachers. Regarding the quality of teacher-student relationships, studies included in

the present review reported a positive relation between SE and teacher-student closeness (Portilla et al., 2014). For example, Rimm-Kaufman and colleagues (2015) found that students

14 in classes with high emotional support from teachers and high levels of classroom

organization reported high cognitive, high emotional, and high social engagement. In this line of search, Hughes and colleagues (2008) suggest that teacher support in elementary years shapes children’s patterns of engagement in learning, which leads to more supportive relationships with subsequent teachers and to higher levels of achievement. Conversely, teacher-student closeness can possibly have a negative effect on SE, depending on the

teacher’s psychological condition (e.g., teachers displaying symptoms of burnout) (Hoglund et al., 2015). Prior research reported that students close to teachers displaying symptoms of burnout exhibited low levels of SE. However, students not holding a close relationship with teachers displaying burnout symptoms showed high levels of SE. Thus, SE is not likely to be dependent on the degree of burnout displayed by teachers, but rather to the level of closeness between students and teachers (Hoglund et al., 2015).

Parents. Of the 15 articles selected in the present systematic review, none mentioned

parents’ interaction with, and support of, their children at school, nor explored their possible influence in the SE of their children.

Impact of interventions on school engagement. A total of 5 articles included

intervention programs related to the promotion of AE (Ling, Hawkins, & Weber, 2011; Miller, Dufrene, Olmi, Tingstrom, & Filce, 2015; Miller, Dufrene, Sterling, Olmi, & Bachmayer,

2015;Mullender-Wijnsma et al., 2015; Ornelles, 2007). The studies reported very diverse

types of intervention, as well as diverse aims and methodologies. However, all studies

assessed the efficacy of the intervention program in fostering AE. In general, results showed a positive impact of the interventions on AE. For example, Ornelles (2007) developed an intervention program with three children signaled as being at-risk for exhibiting school difficulties. Findings showed an increment in the students’ AE, and in the interaction with peers during the intervention. Similarly, Ling and colleagues (2011) investigated the effects of a class intervention on the on/off-task behaviors designed for a particular student exhibiting high rates of off-task behavior and low levels of AE. This tailored intervention was effective for increasing AE and reducing the off-task behaviors. Interestingly, the effects of the intervention were not restricted to the target student, being also observed improvements on overall behavior of the whole class.

15 The effectiveness of another program, more specifically, the Check-in/Check-out

(CICO) program to improve students’ behavioral performance and AE was also assessed in two other studies (Miller et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2015). Both interventions were effective in reducing problematic behaviors and increasing AE for all participants (Miller et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2015). Finally, Mullender-Wijnsma and colleagues (2015) examined the effect of physically active academic lessons on AE, comparing children with, and without, social disadvantage. Findings indicated that all children significantly increased their time-on-task post-intervention. Still, socially disadvantaged children showed lower levels of time-on-task than their counterparts (Mullender-Wijnsma et al., 2015).

All things considered, we can conclude that the interventions run were effective in promoting students’ AE and their levels of time-on-task. Besides, data show that

16

Table 2

Summary of studies included in this review

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Buhs, E. S., Ladd, G. W., & Herald, S. L. (2006).; USA **

Investigate, through a structural model, if chronic peer exclusion and chronic peer abuse mediate the link between children’s early peer rejection, classroom engagement, and achievement.

N= 380 children; 5-11

years of age; Kindergarten to fifth grade.

(Longitudinal study)

Peer exclusion and peer abuse are associated with changes in students’ school and classroom engagement, which predicts changes in academic achievement.

Distinct forms of peer maltreatment and classroom engagement mediate the link between early peer rejection and changes in children’s achievement. Early peer rejection was associated with declining classroom

participation and increasing school avoidance, but different forms of chronic peer maltreatment mediated these

relations. Conversely, chronic peer exclusion principally mediated the link between peer rejection and classroom participation, and chronic peer abuse primarily mediated the link between rejection and school avoidance. Thus, chronically excluded children were more likely to exhibit an increase in classroom disengagement.

Still, higher peer acceptance scores were indirectly associated with increases in classroom participation, decreases in school avoidance, and increases in achievement scores.

Chen, Q., Hughes, J. N., Liew, J., & Kwok, O-M. (2010); USA **

Investigate the effects of peer acceptance and peer academic reputation (PAR) on students' engagement and achievement, and understand the process by which peer relationships affect achievement.

N = 543 relatively low

achieving children; M = 6.57 years at Year 1; first grade.

The effect of PAR on engagement was partially mediated by perceived academic competence. The effect of perceived academic competence on achievement was partially mediated by engagement.

In the context of PAR, peer acceptance did not contribute to the mediating variables or to achievement.

17

Table 2 (continued)

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Galla, B. M., Wood, J. J., Tsukayama, E.,Har, K., Chiu, A. W., & Langer, D. A. (2014); USA *

Examine the effortful engagement and academic self-efficacy’s intra- and inter-person effect on academic performance.

N = 135; 5-12 years of age, M = 8.40 years, SD = 1.54

years; Kindergarten to sixth grade.

Within-person change in Effortful Engagement and Academic Self-Efficacy scores significantly predicted concomitant within-person change in reading test scores. Participants with higher between-person levels of Effortful Engagement had higher initial reading test scores, and math test scores, whereas participants with higher between-person levels of Academic Self-Efficacy showed a faster rate of increase in math test scores across elementary school. At the between-person level, Effortful Engagement mediated the association between Academic Self-Efficacy and both reading and math test scores, although no support was found for mediation at the within-person level. Hoglund, W.L.G., Klingle,

K.E., & Hosan, N.E. (2015); Canada **

Investigate change and variability in teacher burnout and classroom quality, examine how these co-varied over time with each other, and with aggregate externalizing behaviors, adjusting for a set of teacher and classroom characteristics. N = 461; M=6.9 years, SD= 1.19; Kindergarten to third grade N = 65 teachers; M= 37.38 years, SD=11.17;

Kindergarten to third grade.

Average levels of relationship quality with teachers and friends remained stable while school engagement and literacy skills increased significantly over the term. For children who had a not so close relationship with more burned-out teachers, aggregate externalizing behaviors predicted greater increases in teacher–child relationship quality, school engagement, and literacy skills over the term. For children who had a closer relationship with less burned-out teachers, individual externalizing behaviors were associated with lower concurrent levels of school engagement.

For children who were in a closer relationship to less supportive and organized classrooms, aggregate externalizing behaviors were associated with greater increases over the term in school engagement and literacy skills, as well as with higher concurrent levels of friendship quality and school engagement..

18

Table 2 (continued)

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Hughes, J.N., Dyer, N., Luo, W., & Kwok, O.-M. (2009); USA **

Investigate the effects of Peer Academic Reputation (PAR) on academic achievement among students academically at-risk

N = 664; age not reported;

First grade

SEM analyses found that Year 2 PAR predicted Year 3 teacher rating of academic engagement and reading achievement test scores (but not math), above the effects of prior scores on these outcomes.

Furthermore, the effect of PAR on academic engagement and achievement was partially mediated by the effect of PAR on children's academic self-concept.

Hughes, J. N., Luo, W., Kwok, O. M., & Loyd, L. K. (2008); Texas *; **

Test an indirect model of the effect of teacher–student relationship quality (TSRQ) on first-grade children’s academic achievement over a 3-year period, beginning when children were in the first grade. The conceptual model, test if Year 2 effortful engagement mediates the association between Year 1 TSRQ and Year 3 reading and math skills.

N= 671 academically

at-risk children; M at entrance to first grade= 6.57 years, SD = 0.38 years; First grade (Longitudinal study.

Girls scored higher than boys on effortful engagement and had higher reading scores at Time 1.

TSRQ at earlier waves (e.g., TSRQ at Year 1) predicted student effortful engagement at later waves (e.g., engagement at Year 2), with controls for the prior level of effortful engagement (e.g., engagement at Year 1). Similarly, effortful engagement at earlier waves predicted student achievement (reading and mathematics) measured at later waves, with controls for prior levels of achievement.

To summarize, effortful engagement predicted achievement and the effect of effortful engagement on achievement was invariant across developmental periods for both reading and math. Regarding TSRQ, teacher support in elementary years shapes children’s patterns of engagement in learning, which leads to more supportive relationships with subsequent teachers and to higher levels of achievement.

19

Table 2 (continued)

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Hughes, J.N. & Zhang, D. (2007); USA *; **

Examine the effects of classroom indegree (i.e. the degree to which peer nominations as academically capable show high consensus and focus on a relatively few number of children in a classroom) on children’s peer acceptance, teacher-rated classroom engagement, and self-perceived cognitive competence.

N = 291; M = 6.55, SD =

0.33; First grade.

Classroom indegree moderated the associations between students’ achievement and classroom engagement. Children with lower ability, relative to their classmates, were less accepted by peers and less engaged in school. This was true when these children were enrolled in classrooms in which students’ perceptions of classmates’ abilities

converged on a relatively few number of students, compared to classrooms in which peers’ perceptions were more dispersed. High indegree was associated with lower self-perceived cognitive competence regardless of ability level. Iyer, R. V.,

Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., Eisenberg, N., & Thompson, M. (2010); USA *; **

Evaluate if peer victimization and effortful control are predictors of academic achievement through the effects on school engagement.

N = 390; 6 - 10 year, M = 7

years, 6 months, SD = 1 year, 1 month;

First to fourth grades

School engagement mediated the relations between peer victimization and academic achievement, as well as between effortful control and academic achievement.

Ling, S., Hawkins, R. O., & Weber, D. (2011); USA ***

Investigate the effects of a classwide interdependent group contingency on the on/off-task behaviors of an at-risk student.

N =1 boy referred by his

classroom teacher for intervention to address his high rates of off-task behaviors; 8 years old; First grade.

The intervention decreased the individual student’s off-task behaviors and increased academic engagement while also having positive effects on overall behavior in the classroom.

Lynch, A.D., Lerner, R. M., & Leventhal, T. (2012); USA **

Investigate the potential relationship between school’s relational and behavioral peer culture and individual academic outcomes, i.e. individual grades and school engagement.

N = 1718 (first period of

data collection); M = 10.99,

SD = 0.01; Fifth grade

(longitudinal study in which in the second wave of data collection only 10% of participants remained)

Behavioral and relational aspects of peer culture are associated to individual achievement and school

engagement, with levels of school engagement increasing as peer culture becomes more positive.

20

Table 2 (continued)

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Miller, L.M., Dufrene, B.A., Joe Olmi, D., Tingstrom, D., & Filce, H. (2015); USA ***

To provide an empirical demonstration of the effects of Check-in/Check-out (CICO) within SWPBIS (School-wide positive behavior interventions and support) on students' academic engagement and disruptive behaviour.

N = 4; age not reported;

Kindergarten through 4th grade

All students reduced the frequency of disruptive behaviors and increased academic engagement, which were associated with CICO.

Miller, L. M., Dufrene, B. A., Stearling, H. E., Olmi, D. J., & Bachmayer, E. (2015); USA ***

Evaluate the effectiveness of Check-in/Check-out (CICO) for improving behavioral performance of three students referred for Tier 2 behavioral supports.

N = 3; age not reported

Second, fourth, and sixth grades

Through direct observation of students’ behavior was observed an increase of academic engagement and a decrease of problematic behaviors for all target students.

Moller, S., Stearns, E., Mickelson, R.A., Bottia, M.C., Banerjee, N. (2014); USA *

Investigate in which way Collective Pedagogical Teacher Culture (i.e. professional community) moderates the relationship between academic engagement and mathematics achievement for students of different racial/ethnic groups in elementary school.

N = 5360; age not reported;

First, third, and fifth grade

Academic engagement is a strong predictor of mathematics achievement in all grades and for all racial groups. The students that obtained higher results in mathematics were the most attentive, persistent, independent, flexible, and organized students. Students without these skills are highly disadvantaged and this disadvantage cumulates over time. Additionally, school organizational culture moderated the relationship between engagement and achievement. Mullender-Wijnsma, M.J.,

Hartman, E., de Greeff, J.W., Bosker, R. J.,

Doolaard, S., & Visscher, C. (2015); Netherlands ***

Examine the effect of physically active academic lessons on academic engagement of socially

disadvantaged students and students non-socially disadvantaged. The relationship between lesson time spent in moderate to vigorous physical activity and academic engagement was also examined.

N = 86; M = 8.2 years, SD =

0.65 years; Second or third grades

Socially disadvantage students evidenced lower time-on-task than students without the disadvantage, being the differences noted in different moments. All students evidenced significant increases on the time-on-task (academic engagement) on the post-intervention condition. On average, students were exercising in moderate to vigorous physical activity during 60% of the lesson time; however, no significant relationships were found between percentage of moderate to vigorous physical activity during the intervention and time-on-task (academic engagement) in the post-intervention lessons.

21

Table 2 (continued)

Reference; country Purpose Participants

Number of participants; age; school year

Results

Ornelles, C. (2007); USA ***

Evaluate the effects of a structured intervention on engagement, and initiations of interaction with other students, of 3 children identified as at-risk for school difficulty.

N = 3; 6 - 6.5 years; First

grade

During the intervention, all students increased their engagement in academic activities, initiations, and interactions with peers.

Portilla, X. A., Ballard, P. J., Adler, N. E., & Obradovic, J. (2014); USA *; **

Investigate the dynamic interplay between teacher–child relationship quality and children’s behaviors across kindergarten and first grade to predict academic competence in first grade.

N = 338; M at kindergarten

entry = 5.31 years, SD = 0.32, range = 4.75–6.28 years; Kindergarten to first grade.

School engagement is positively related to teacher-child closeness and with academic competence in the first grade and negatively related to inattention, impulsivity, and conflict.

Low self-regulation in the Autumn, as indexed by

inattention and impulsive behaviors, predicted more conflict with teachers in the Spring and this effect persisted into first grade. Conflict and low self-regulation jointly predicted decreases in school engagement, which in turn predicted first-grade academic competence.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Larsen, R. A. A., Baroody, A. E., Curby, T. W., & Abry, T. (2015); USA **

Examine concurrent teacher–student interaction quality and students’ engagement in mathematics classrooms and understand how teacher–student interaction quality relates to engagement (differently for boys and girls).

N = 387; M = 10.47, SD =

0.37; Fifth grade

N = 63 fifth grade

mathematics teachers

Students that received higher emotional support in classrooms, and that have class more organized, reported higher cognitive, emotional, and social engagement. Interaction effects were present for student-reported engagement outcomes but not in observed or teacher-reported engagement.

Boys (but not girls) in classrooms with higher observed classroom organization reported more cognitive and emotional engagement. In classrooms with higher instructional support, boys reported higher, but girls reported lower, social engagement.

* School engagement and academic achievement

** The role of class peers, teachers, or parents on school engagement *** Impact of interventions on academic engagement

22

Discussion

Recently, SE has been receiving the attention from researchers interested in

investigating the process of SE (e.g., relationships between SE and outcome variables, and the promotion of SE), especially in populations with a high likelihood of failing or early school leaving. The present systematic review provides information about the research conducted in the last ten years on SE in elementary school, with particular emphasis on the relationships between SE and academic achievement, and also on the role played by close interveners such as peers, teachers, and parents in students’ SE.

Consistent with findings from other school levels, our study shows SE as a strong predictor of school achievement in elementary school, specifically in mathematics and reading (Galla et al., 2014; Hughes & Zhang, 2007; Iyer et al., 2010; Moller et al., 2014). This fact is further sustained by research indicating that students engaged in school, and with a sense of connection with the teacher and the class, are more likely to be involved in their learning process and achieve higher grades than their counterparts (e.g., Reyes, Brackett, Rivers, White, & Salovey, 2012). For example, students who enroll in

emotionally responsive classes are more likely to feel a sense of belonging in school and of engaging in school and school activities (Reyes et al., 2012). In contrast, when students feel disconnected from school, the likelihood of engaging with school work is low. This proposition emphasizes the role played by students’ schooling experiences in the

development of their SE (Wang & Holcombe, 2010). In fact, students with low engagement in school are likely to lose their interest in studying, which could have an impact on achievement and, ultimately, resulting in early dropout from school (Li & Lerner, 2011; Wonglorsaichon, Wongwanich, & Wiratchai, 2014).

Regarding the role of class peers, teachers, or parents’ interaction in students’ SE, the results of the studies selected were consistent. Class peers interaction can be

considered as highly influential on SE, with SE being closely related with the peer culture (Lynch et al., 2012). Indeed, relationships with peers could be positively or negatively associated with SE. For example, when peer’s relationships are characterized by peer victimization, students report low levels of SE; besides, victimization is associated with the development of negative attitudes towards school (Iyer et al., 2010) and with school avoidance (Buhs et al., 2006). Students’ peer acceptance and students’ perception of

23 competence are also variables that may positively or negatively influence SE (Chen et al., 2010; Hughes et al., 2009; Hughes & Zhang, 2007). For example, for low achievers, class peers’ perceptions of their competence are likely to significantly influence their academic life. Specifically, low achievers tend to be less accepted by their class peers and,

consequently, be less engaged with school (Hughes & Zhang, 2007). On the other hand, high achievers tend to be more accepted by their colleagues and, generally, be more engaged with school (Hughes & Zhang, 2007).

The relationship between teachers and students was also found to influence SE. Similar to class peers interaction, the quality of the teacher-student relationship may positively or negatively impact SE. In classes in which students feel supported by their teachers, the reported engagement levels were higher than those of students in classes with low perceived support (Portilla et al., 2014; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2015). However, research stressed the importance of qualifying the nature of such a relationship due to its complexity. For example, for students holding a close relationship with teachers

displaying burnout symptoms, the effect of teachers’ closeness on SE can be adverse (Hoglund et al., 2015). Acknowledging these cautions, research has been highlighting the central role played by teachers in the promotion of SE by, for example, providing students with needed support (Skinner, Furrer, Marchand, Kindermann, 2008) and modelling students’ engagement in learning (Hughes et al., 2008). In fact, students holding a close relationship with their teachers and, thus, benefiting from teachers’ support and

responsiveness are likely to invest their own resources such as time, effort, commitment, and persistence in their school work, with expected improvements in their learning (Krause & Coates, 2008; Reyes, et al., 2012; Skinner et al., 2008).

As mentioned in the results section, none of the articles selected addresses the role of parents on SE of elementary students. Nevertheless, a study developed by Estell and Purdue (2013) indicated a positive association between parents’ support and students’ SE. Findings show that students whose parents provide more supportive behaviors, and are more socially involved with their children, showed higher levels of SE than their counterparts. This outcome depicts one of the shortcomings of systematic literature reviews. Despite the broad research terms employed in the search phase, the paper by

24 Estell and Purdue (2013) did not appear when searches were conducted in the three

databases, with the six combinations of search terms used.

When examining the intervention programs run with the aim of promoting SE, we can conclude that there are a variety of effective ways to promote SE. Despite the

diversity of modalities of intervention, in this review, the type of intervention mainly used was group intervention (Ling et al., 2011; Miller et al., 2015; Miller et al., 2015;

Mullender-Wijnsma et al., 2015; Onelles, 2007), being some of the interventions applied in the classroom context (Ling et al., 2011; Mullender-Wijnsma et al., 2015). Importantly, all interventions were effective in promoting SE. This proposition allows for the

conclusion that SE could be promoted through a variety of ways, while considering the characteristics of the target population and the context of where the intervention will take place, in order to increase the chances of improving SE. Besides, as Wang and colleagues (2011) alerted, to increase effectiveness, SE interventions should integrate different strategies addressing students’ needs in the three SE dimensions.

In conclusion, the evidence presented in this systematic review suggests that SE and academic achievement are related variables, being positively associated. Overall, SE is considered a predictor of academic achievement in elementary school students, and is positively related to academic competence (Iyer, et al., 2010; Portilla et al., 2014). Regarding the role of peers and teachers in the SE of elementary school students, results suggest that peer relationships and the quality of teacher-students relationship have significant impacts on students’ SE. Focusing on the role of parental support and

interaction with their children in elementary school student’s engagement, results were not enlightening. Despite authors likeSylva, Scott, Totsika, Ereky-Stevens and Crook (2008) arguing about the importance of the parental support (e.g., emotional understanding of their children’s problems), its relationship or impact on SE is yet to be deeply explored in literature. Finally, many intervention programs proved to be effective in the promotion of SE, which indicates that there is a large range of possibilities to improve SE using distinct frameworks.

25

Limitations and future research directions

The current review is constrained by a few limitations that future research may want to address. Despite the selection of studies had followed PRISMA statement and Cochrane’s guidelines to ensure that studies selected are of high quality and to prevent publication bias, authors cannot guarantee the full access to all data in this particular domain. Indeed, SE has been largely investigated in recent years, in different school levels, and with different purposes. Still, besides the considerably large number of studies focused on SE, the majority did not match the purpose of the present review and, for this reason, were not included. Another limitation is related to the publication bias, i.e. studies with non-significant results are rarely submitted and rarely accepted for publication; hence, the published literature on SE may be unrepresentative of the set of completed studies within the domain.

An important contribution of the present systematic review was the identification of shortcomings that could be addressed in future research. Additional research is needed to explore the relationship between SE and parental support, and to examine which types of parenting skills to endow parents with that may help promote or improve their

children’s SE levels. Future studies may want to address the topic of teachers-students relationships and which practices, or strategies, are likely to improve students’ SE. Finally, further research is needed to deepen our understanding on how intervention programs could be designed to successfully increase elementary students’ SE. In

particular, it is important to consider the context of where the intervention will take place, the characteristics of the target population (such as age, school year, ethnicity, behavioral or emotional disorders), the type and duration of the intervention, and its specific aims.

Conclusions

To conclude, this study stresses that SE positively impacts students’ learning process and achievement, including in elementary school students. Besides, class peers, teachers, and parents play a crucial role in promoting elementary students’ SE.

26 References

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R., & Kabbani, N. S. (2001). The dropout process in life course perspective: Early risk factors at home and school. Teachers College Record, 103(5), 760–822. doi: 10.1111/0161-4681.00134.

Buhs, E. S., Ladd, G. W., & Herald, S. L. (2006). Peer exclusion and victimization: Processes that mediate the relation between peer group rejection and children's classroom engagement and achievement? Journal of Educational Psychology, 98(1), 1-13. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.1.

Buijs, M., & Admiraal, W. (2013). Homework assignments to enhance student engagement in secondary education. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(3), 767– 779. doi: 10.1007/s10212-012-0139-0.

Christenson, S. L., Reschly, A. L., Appleton, J. J., Berman, S., Spanjers, D., & Varro, P. (2008). Best practices in fostering student engagement. In A. Thomas, & J. Grimes (Eds.), Best Practices in School Psychology (pp. 1099 – 1120). Bethesda, MD: National Association of School Psychologists.

Christenson, S. L., & Reschly, A. L. (2012). Jingle, jangle, and conceptual haziness: Evolution and future directions of the engagement construct. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 3-19). New York, NY: Springer.

Dotterer, A. M., & Lowe, K. (2011). Classroom context, school engagement, and academic achievement in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(12), 1649– 1660. doi: 10.1007/s10964-011-9647-5.

27 Estell, D., & Perdue, N. (2013). Social support and behavioral and affective school

engagement: the effects of peers, parents, and teachers. Psychology in the Schools, 50(4), 325-339. doi: 10.1002/pits.21681.

Finn, J. D. (2006). The adult lives of at-risk students: The roles of attainment and engagement in high school. (NCES 2006-328). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics, U.S. Department of Education.

Finn, J. D., & Zimmer, K. S. (2012). Student engagement: What is it? Why does it matter? In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 97-131). New York, NY: Springer.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. doi: 10.3102/00346543074001059.

Galla, B., Wood, J., Tsukayama, E.,Har, K., Chiu, A., & Langer, D. (2014). A longitudinal multilevel model analysis of the within-person and between-person effect of effortful engagement and academic self-efficacy on academic performance. Journal of School Psychology, 52(3), 295-308. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.04.001.

Chen, Q., Hughes, J. N., Liew, J., & Kwok, O. M. (2010). Joint contributions of peer acceptance and peer academic reputation to achievement in academically at-risk children: Mediating processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 31(6), 448-459. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2010.09.001.

Gottfried, A. E., Marcoulides, G. A., Gottfried, A.W., Oliver, P. H., & Guerin, D.W. (2007). Multivariate latent change modeling of developmental decline in academic intrinsic math motivation and achievement: Childhood through adolescence. International

28

Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(4), 317–327. doi:

10.1177/0165025407077752.

Hagger, M. S., Sultan, S., Hardcastle, S. J., & Chatzisarantis, N L. D. (2015). Perceived autonomy support and autonomous motivation toward mathematics activities in educational and out-of-school contexts is related to mathematics homework behavior and attainment. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 41, 111–123. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.002.

Handelsman, M., Briggs, W., Sullivan, N., & Towler, A. (2010). A measure of college student course engagement. The Journal of Education Research, 98(3), 184-192. doi: 10.3200/JOER.98.3.184-192.

Heng, K. (2014). The Relationships between Student Engagement and the Academic Achievement of FirstYear University Students in Cambodia. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 2(23), 179-189. doi: 10.1007/s4029901300958.

Higgins, J., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Retrieved October 21, 2015, from http://handbook.cochrane.org/

Hirschfield P. J., & Gasper J. (2011). The relationship between school engagement and delinquency in late childhood and early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(1), 3–22. doi: 10.1007/s10964-010-9579-5.

Hoglund, W. L., Klingle, K. E., & Hosan, N. E. (2015). Classroom risks and resources: Teacher burnout, classroom quality and children's adjustment in high needs elementary schools. Journal of School Psychology, 53(5), 337-357. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2015.06.002. Horstmanshof, L., & Zimitat, C. (2007). Future time orientation predicts academic

engagement among first-year university students. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(3), 703-718. doi: 10.1348/000709906X160778.

29 Hughes, J. N., Dyer, N., Luo, W., & Kwok, O. M. (2009). Effects of peer academic

reputation on achievement in academically at-risk elementary students. Journal of

Applied Developmental Psychology, 30(2), 182-194. doi:

10.1016/j.appdev.2008.12.008.

Hughes, J. N., Luo, W., Kwok, O. M., & Loyd, L. K. (2008). Teacher-student support, effortful engagement, and achievement: A 3-year longitudinal study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 1-14. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.1.

Hughes, J. N., & Zhang, D. (2007). Effects of the structure of classmates’ perceptions of peers’ academic abilities on children’s perceived cognitive competence, peer acceptance, and engagement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 32(3), 400-419. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2005.12.003.

Iyer, R. V., Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., Eisenberg, N., & Thompson, M. (2010). Peer victimization and effortful control: Relations to school engagement and academic

achievement. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 56(3), 361-387. doi:10.1353/mpq.0.0058.

Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 262-273.doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2004.tb08283.x.

Krause, K. L., & Coates, H. (2008). Students’ engagement in first-year university. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(5), 493–505. doi: 10.1080/02602930701698892.

Lee, J. (2014). The relationship between student engagement and academic performance: Is it a myth or reality?. The Journal of Educational Research, 107(3), 177-185. doi: 10.1080/00220671.2013.807491.

30 Li, Y., & Lerner, R. M. (2011). Trajectories of school engagement during adolescence:

Implications for grades, depression, delinquency, and substance use. Developmental Psychology, 47(1), 233–347. doi: 10.1037/a0021307.

Ling, S., Hawkins, R. O., & Weber, D. (2011). Effects of a classwide interdependent group contingency designed to improve the behavior of an at-risk student. Journal of Behavioral Education, 20(2), 103-116. doi: 10.1007/s10864-011-9125-x.

Lynch, A. D., Lerner, R. M., & Leventhal, T. (2012). Adolescent academic achievement and school engagement: An examination of the role of school-wide peer culture. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 42(1), 6–19. doi: 10.1007/s10964-012-9833-0.

Mahatmya, D., Lohman, B. J., Matjasko, J. L., & Amy Feldman Farb, A. F. (2012). Engagement across developmental periods. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 45-63). New York, NY: Springer.

Miller, L. M., Dufrene, B. A., Olmi, D. J., Tingstrom, D., & Filce, H. (2015). Self-monitoring as a viable fading option in check-in/check-out. Journal of School Psychology, 53(2), 121-135. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2014.12.004.

Miller, L. M., Dufrene, B. A., Sterling, H. E., Olmi, D. J., & Bachmayer, E. (2015). The effects of check-in/check-out on problem behavior and academic engagement in elementary school students. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 17(1), 28-38. doi: 10.1177/1098300713517141.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D., & Group, T. P. (2009). Preferred

Reporting/items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Retrieved October 21, 2015, from http://www.prisma-statement.org/

31 Engagement the Panacea for Achievement in Mathematics across Racial/Ethnic Groups? Assessing the Role of Teacher Culture. Social Forces, 92(4), 1513-1544. doi: 10.1093/sf/sou018.

Mullender-Wijnsma, M. J., Hartman, E., de Greeff, J. W., Bosker, R. J., Doolaard, S., & Visscher, C. (2015). Moderate-to-vigorous physically active academic lessons and academic engagement in children with and without a social disadvantage: a within subject experimental design. BMC Public Health, 15(404), 1-9. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1745-y.

Núñez, J. C., Rosário, P., Vallejo, G., & González-Pienda, J. A. (2013). A longitudinal assessment of the effectiveness of a school-based mentoring program in middle school.

Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(1), 11–21. doi:

10.1016/j.cedpsych.2012.10.002.

OECD (2012). PISA 2012 Results: What Students Know and Can Do – Student Performance

in Mathematics, Reading and Science (Volume I). Available in

http://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-volume-I.pdf.

Ornelles, C. (2007). Providing classroom-based intervention to at-risk students to support their academic engagement and interactions with peers. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 51(4), 3-12. doi: 10.3200/PSFL.51.4.3-12.

Portilla, X. A., Ballard, P. J., Adler, N. E., Boyce, W. T., & Obradović, J. (2014). An integrative view of school functioning: Transactions between self‐regulation, school engagement, and teacher–child relationship quality. Child Development, 85(5), 1915-1931. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12259.

32 Reyes, M. Brackett, M. Rivers, S. White, M., & Salovey, P. (2012). Classroom emotional

climate, student engagement, and academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 700-712. doi: 10.1037/a0027268.

Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., Larsen, R. A. A., Abry, T., Baroody, A. E., & Curby, T. W. (2015). To what extent do teacher–student interaction quality and student gender contribute to fifth graders’ engagement in mathematics learning? Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(1), 170-185. doi: 10.1037/a0037252.

Rosário, P., Núñez, J.C., Ferrando, P., Paiva, O., Lourenço, A., Cerezo, R., & Valle, A. (2013). The relationship between approaches to teaching and approaches to studying: A two-level structural equation model for biology achievement in high school. Metacognition and Learning, 8(1), 44-77. doi: 10.1007/s11409-013-9095-6.

Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Rodríguez, C., Cerezo, R., Fernández, E., Tuero, E., &Högemann, J. (2015). Analysis of instructional programs for improving self-regulated learning SRL through written text. In R. Fidalgo, K. Harris, & M. Braaksma (Eds.), Design Principles for Teaching Effective Writing (pp. 1-37). Leiden: Brill Editions.

Rosário, P., Núñez, J. C., Vallejo, G., Cunha, J., Azevedo, R., Pereira, R., … & Moreira, T. (2015). Promoting Gypsy children school engagement: A story-tool project to enhance self-regulated learning. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 44-45, 1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2015.11.005.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 571-581. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.85.4.571.

33 Skinner, E., Furrer, C., Marchand, G., & Kindermann, T. (2008). Engagement and

disaffection in the classroom: Part of larger motivational dynamic. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(4), 765-781. doi: 10.1037/a0012840.

Skinner, E. A., Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., & Connell, J. P. (1998). Individual differences and the development of perceived control. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 63, 2–3. Whole No. 204.

Sylva, K., Scott, S., Totsika, V., Ereky‐Stevens, K., & Crook, C. (2008). Training parents to help their children read: A randomized control trial. British Journal of Educational

Psychology, 78(3), 435-455.doi: 10.1348/000709907x255718.

Upadyaya, K., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2013). Development of school engagement in association with academic success and well-being in varying social contexts: A review of empirical research. European Psychologist, 18(2), 136–147. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000143.

Virtanen, T. E., Lerkkanen, M. K., Poikkeus, A. M., & Kuorelahti, M. (2014). Student behavioral engagement as a mediator between teacher, family, and peer support and school truancy. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 201-206. doi: doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2014.09.001.

Wang, M., & Fredricks, J.A. (2013). The reciprocal links between school engagement, youth problem behaviors, and school dropout during adolescence. Child Development, 85(2), 722–737. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12138.

Wang, M., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662. doi: 10.3102/0002831209361209.

34 Wang, M., Willett, J. B., & Eccles, J. S. (2011). The assessment of school engagement:

Examining dimensionality and measurement invariance by gender and race/ethnicity. Journal of School Psychology, 49(4), 465–480. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.04.001.

Wonglorsaichon, B., Wongwanich, S., & Wiratchai, N. (2014). The influence of students school engagement on learning achievement: A structural equation modeling analysis.

Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 1748-1755. doi:

10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.467.

Wyatt, L. (2011). Nontraditional student engagement: Increasing adult student success and retention. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 59(1), 10-20. doi: 10.1080/07377363.2011.544977.