ContentslistsavailableatScienceDirect

Carbohydrate

Polymers

jo u r n al h om ep a g e :w w w . e l s e v i e r . c o m / l o c a t e / c a r b p o l

Polysaccharides

isolated

from

Digenea

simplex

inhibit

inflammatory

and

nociceptive

responses

Juliana

G.

Pereira

a,

Jacilane

X.

Mesquita

a,

Karoline

S.

Aragão

b,

Álvaro

X.

Franco

b,

Marcellus

H.L.P.

Souza

b,

Tarcisio

V.

Brito

c,

Jordana

M.

Dias

c,

Renan

O.

Silva

c,

Jand-Venes

R.

Medeiros

c,

Jefferson

S.

Oliveira

c,

Clara

Myrla

W.S.

Abreu

d,

Regina

Célia

M.

de

Paula

d,

André

Luiz

R.

Barbosa

c,∗,

Ana

Lúcia

P.

Freitas

a,∗∗aLaboratoryofProteinsandCarbohydratesofMarineAlgae,DepartmentofBiochemistryandMolecularBiology,FederalUniversityofCeará,Fortaleza,

Brazil

bLAFICA–LaboratoryofPharmacologyofInflammationandCancer,DepartmentofPhysiologyandPharmacology,FederalUniversityofCeará,Fortaleza,

CE,Brazil

cLAFFEX–LaboratoryofExperimentalPhysiopharmacology,BiotechnologyandBiodiversityCenterResearch(BIOTEC),FederalUniversityofPiauí,

Parnaiba,Piauí,Brazil

dPolymerLaboratory,DepartmentofOrganicandInorganicChemistry,FederalUniversityofCeará,Fortaleza,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received5December2013

Receivedinrevisedform20January2014 Accepted22January2014

Availableonline12March2014

Keywords:

Polysaccharides Anti-inflammatory Antinociceptive

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Polysaccharides(PLS)havenotablydiversepharmacologicalproperties.Inthepresentstudy,we inves-tigatedthepreviouslyunexploredanti-inflammatoryandantinociceptiveactivitiesofthePLSfraction isolatedfromthemarineredalgaDigeneasimplex.WefoundthatthePLSfractionreduced carrageenan-inducededemainadose-dependentmanner,andinhibitedinflammationinducedbydextran,histamine, serotonin,andbradykinin.Thefractionalsoinhibitedneutrophilmigrationintobothmousepawand per-itonealcavity.ThiseffectwasaccompaniedbydecreasesinIL1-andTNF-␣levelsintheperitonealfluid. Pre-treatmentofmicewithPLS(60mg/kg)significantlyreducedaceticacid-inducedabdominalwrithing. ThissamedoseofPLSalsoreducedtotallickingtimeinbothphasesofaformalintest,andincreased latencyinahotplatetest.Therefore,weconcludethatPLSextractedfromD.simplexpossess anti-inflammatoryandantinociceptiveactivitiesandcanbeusefulastherapeuticagentsagainstinflammatory diseases.

©2014ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

1. Introduction

Presently,about25–30%ofallactivecompoundsthatareused astherapeutictreatmentsarederivedfromnaturalproducts(Silva, Moura,Oliveira,Diniz,&Barbosa-Filho,2003),andnaturalmarine products have been the focus for the efforts to discover new molecules of pharmacological and biomedical interest (Cabrita, Vale,&Rauter,2010;Iannitti&Palmieri,2010)Marinealgaehave receivedspecialattentionsincetheyhavebeenshowntobe valu-ablesourcesofstructurallydiversebioactivecompounds,suchas polyphenols,carotenoids,pigments,enzymes,andpolysaccharides (PLS)(Kusaykinetal.,2008;Wijesekara,Pangestuti,&Kim,2010).

∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+558699131650.

∗∗Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+558533669819.

E-mailaddresses:andreluiz@ufpi.edu.br(A.L.R.Barbosa),pfreitas@ufc.br

(A.L.P.Freitas).

Manyspeciesofseaweed(marinemacroalgae)areusedasfood andintraditionalmedicinebecauseoftheirperceivedhealth ben-efits.RedSeaweedsaresourcesofPLS,includingsomethathave becomevaluableadditivesinthefoodindustrybecauseoftheir rhe-ologicalproperties(Kusaykinetal.,2008;Wijesekaraetal.,2010). Inaddition,thesePLShaveanumberofbiologicalactivities, includ-inganticoagulant,antiviral,gastroprotective,antinociceptive,and anti-inflammatoryproperties(Britoetal.,2013;Chavesetal.,2013; Cumashietal.,2007;Silvaetal.,2011).

TheRedSeaweedDigeneasimplex(Wulfen)C.Agardh,a mem-beroftheRhodomelaceaefamily,isusedextensivelyinJapanas a parasiticide, and considereda good source of agar(El-Sayed, 1983;Tomoda,Nakatsuka,&Minami,1972).Inapreviousstudy, thegalactancontentinthePLSofD.simplexwasinvestigatedby ionexchange chromatography,massspectrometry,andinfrared analysisandwasfoundtoberichincommonrepeatinggalactan sulfatebackbones(Takano,Shiomoto,Kamei,Hara,&Hirase,2003). However,nostudydemonstratingthechemicalcharacteristicsof

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.carbpol.2014.01.105

thepolysaccharidefractionofthisalgawithhabitatinBrazilwas performedpreviously.

The inflammatory process is a temporally controlled phe-nomenon involving the participation of diverse mediators including histamine, serotonin, bradykinin, TNF-␣, IL-1, and prostaglandins,andisassociatedwithintensemigration of neu-trophilsfromthebloodintoinflamedtissues(Carvalhoetal.,1996; Hajareetal.,2001;Srinivasanetal.,2001).Thebiochemical medi-atorstogetherstimulateasequenceofmolecularevents,aswellas inflammationandnociception(Déciga-Campos,Palacios-Espinosa, Reyes-Ramírez,&Mata,2007;Moncada&Higgs,1993).Itisclear thatthereisastrongassociationbetweentheinflammatoryprocess andthedevelopmentofpain.Inflammatorypain,producedbythe actionofinflammatorymediators,isaccompaniedbytheincreased excitabilityofperipheralnociceptivesensoryfibers(Linley,Rose, Ooi,&Gamper,2010).Interestingly,therearenomarine-derived anti-inflammatorynaturalproductsinclinicaldevelopment cur-rently(Mayeretal.,2010).

Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate the antinociceptiveand anti-inflammatoryactivitiesof a previously characterizedPLSfractionwasisolatedfromthemarineredalgaD. simplexbyusingexperimentalmodelsofinflammationand noci-ception.

2. Experimental

2.1. Extractionofpolysaccharide(PLS)

TheextractionofthepolysaccharideofGracilariabirdiaewas accomplishedattheLaboratoryofBiochemistryofSeaAlgaeatthe DepartmentofBiochemistryandMolecularBiologyoftheFederal UniversityofCeará.TheRedSeaweedwasharvestedatFlexeiras Beach,Trairí,Ceará,Brazil,inDecember1991,geographical local-ization:03◦13′25′′Sand 39◦16′65′′W.A voucher specimen(No.

4693)wasdepositedintheHerbariumPriscoBezerra,Federal Uni-versityofCeará,Brazil.Samplescleanedofepiphyteswerewashed withdistilled waterand thensubmittedtoextractionand frac-tionationin ordertoobtainof PLSusingexperimentalprotocol previouslydescribed(Takanoetal.,2003).Thedriedtissue(5g) wasmilledandsuspendedin250mLof0.1Msodiumacetatebuffer (pH5.0)containing30mgofpapain(E.Merck),5mMEDTA,5mM cysteineandincubatedat60◦Cfor6h.Theresiduewasremoved

byfiltrationandcentrifugedat2725×gfor30minat4◦C.ThePLS

wereprecipitatedbytheadditionof48mLof10%cetylpyridinium chloride(CPC,SigmaChemical).Themixturewascentrifugedat 2725×gfor30minat4◦C.Thepolysaccharidesinthepelletwere

washedwith200mLof0.05%cetylpyridiniumchloridesolution, andthenprecipitatedwith200mLofethanol(v/v),for24hat4◦C.

Afterfurthercentrifugation(2725×gfor30minat4◦C),the

pre-cipitatewaswashedtwicewith200mLof80%ethanolanddried withacetoneunderhotairflow(60◦C).

2.2. Infraredspectroscopy

Fouriertransforminfrared(FT-IR)spectraofKBrpelletsofthe polysaccharideswererecordedinaShimadzuIRspectrophotomer (model8300)scanningbetween400and4000cm−1.

2.3. Nuclearmagneticresonancespectroscopy

13CNMRspectraof2.5%w/vsolutionsinD

2Owererecordedat

353KonaFouriertransformBrukerAvanceDRX500spectrometer withaninversemultinucleargradientprobe-headequippedwith z-shieldedgradientcoils,andwithSiliconGraphics.Acetonewas usedastheinternalstandard(31.07ppmfor13C).

2.4. Animals

Male Swiss mice weighing 20–25g were used. The animals werehousedintemperature-controlledroomsandreceivedfood andwateradlibitum.Allexperimentswereconductedin accor-dancewiththecurrentlyestablishedprinciplesforthecareanduse ofCOBEA(ColégioBrasileirodeExperimentac¸ãoAnimal),Brazil. TheAnimalStudiesCommitteeofUniversidadeFederaldoCeará approvedtheexperimentalprotocol.

2.5. Carrageenan-inducedpawedema

The animals were randomly divided into 6 groups (n=5), and edemawas inducedbythe injectionof 50L ofa suspen-sionofcarrageenan (500g/paw)in0.9% sterilesalineintothe right hind paw (group I). The mice were pretreated intraperi-toneally(i.p.)witheither0.9%NaCl(groupII,untreatedcontrol), 10mg/kg indomethacin(group III,reference control),or10, 30, or60mg/kgofPLS(groupsIV,V,andVI,respectively)1hbefore carrageenaninjection.Pawvolumewasmeasuredwitha plethys-mometer (Panlab, Barcelona, Spain) immediately before (Vo), and at 1, 2, 3, and 4h after carrageenan treatment (Vt) as previously described (Winter, Risley, &Nuss, 1962).The effect of pre-treatment was calculated as the percentage of inhibi-tionof edema relativetothepawvolume ofthesaline-treated controlsas previously described (Lanhers, Fleurentin, Dorfman, Mortier,&Pelt,1991)accordingtothefollowingformula:% inibi-tion of edema=(Vt−Vo)“Control”−(Vt−Vo)“Treated”)/(Vt−Vo)

“Control”)×100.

2.6. Pawedemainducedbydifferentinflammatoryagents

To induce paw edema with different inflammatory agents, theanimalswereadministered50-Linjectionsofdextran(DXT,

500g/paw),serotonin(Ser,1%,w/v),histamine(Hist,1%,w/v), or bradykinin (Bk, 6nmol) into theright hindpaw. Onegroup received50Lof0.9%sterilesalineandservedasanuntreated con-trolgroup.PLS(60mg/kg)orindomethacin(10mg/kg,reference control)wereinjectedi.p.30minbeforeintraplantarinjectionsof phlogisticagents.Pawvolumewasmeasuredimmediatelybefore, andatselectedintervaloftime.

2.7. Determinationofmyeloperoxidaseactivity

Theextentofneutrophilaccumulationinthemousepawwas measuredusingamyeloperoxidase(MPO)assay.ToevaluateMPO activity,carrageenanwasinjectedintotherightplantarsurfaceof themicepre-treatedwithsaline,carrageenan,indomethacin,orPLS (60mg/kg).Fourhoursaftercarrageenaninjection,wemeasured theMPOconcentrationintherighthindpaw.Briefly,50–100mg ofhindpawtissuewashomogenizedin1mLofpotassiumbuffer with0.5%hexadecyltrimethylammoniumbromide(HTAB)foreach 50mgoftissue.Thehomogenatewascentrifugedat40,000×gfor 7minat4◦C.MPOactivityintheresuspendedpelletwasassayed

by measuringthechange inabsorbance at 450nm by usingo -dianisidinedihydrochlorideand1%hydrogenperoxide.Theresults arereportedasMPOunits/mgtissue.AunitofMPO(UMPO)activity wasdefinedasthatconverting1mmolhydrogenperoxidetowater over1minat22◦C.

2.8. Peritonitismodel

Mice were injected orally with 250L of sterile saline,

Fig.1. FT-IRspectra(A)inKBrpellets;NMRspectrainD2O,(B)13C-NMRspectrum

s,(C)DEPTspectrumofPLSfromD.simplex.

cavitywaswashedwith1.5mLofheparinizedphosphate-buffered saline(PBS)toharvestthecellscontainedintheperitonealfluid. TotalcellcountswereperformedusingaNeubauerchamber,and differentialcellcounts(100cellstotal)werecarriedoutusing cyto-centrifugeslidesstainedwithhematoxylinandeosin.Theresults

arepresentedasthenumberoftotalleucocytesorneutrophilsper milliliterofperitonealexudates.

2.9. MeasurementofIL-1ˇandTNF-˛

Aftertheperitonitisassay,samplesofperitonealfluidwere col-lectedandthelevelsofIL-1andTNF-␣wereevaluatedusinga sandwichenzyme-linkedimmunosorbentassay(ELISA).ELISAkits forIL-1wereobtainedfromtheNationalInstitutefor Biologi-calStandardsandControl(PottersBar,UK).Thekitsconsistently showedIL-1andTNF-␣levelstobeover4000pg/mLandthatthey didnotcross-reactwithothercytokines.Theresultsareexpressed aspg/mLofeachcytokineperperitonealcavitywashed.

2.10. Aceticacid-inducedwrithingtest

Theacetic-acidwrithingtest wasusedtoevaluatethe anal-gesicactivity(Collier,Dinneen,Johnson,&Schneider,1968)ofPLS. The mice(n=6 per group) wereinjected (i.p.)with 0.6%acetic acid(10mL/kgbodyweight),andtheintensityofnociceptionwas quantifiedbycountingthetotalnumberofwrithesoveraperiod of20min,andincludedabdominalmusclecontractionsandhind pawextensions(Koster,Anderson,&De-Beer,1959).Theanimals receivedPLS(60mg/kg,i.p.)orsterilesaline(controlgroup,0.9%, w/v)30minbeforeaceticacidinjection.Morphine(5mg/kg,s.c.) wasadministered30minbeforeaceticacidasareferencecontrol.

2.11. Formalintest

Thistest,whichresultsinalocaltissueinjurytothepaw,has beenusedasamodelfortonicpainandlocalizedinflammatorypain (Hunskaar,Fasmer,&Hole,1985).Twentymicrolitersof2.5% for-malinwasadministered(s.c.)intotherighthindpaw.Theamount oflickingtimewasrecordedfrom0to5min(phase1,neurogenic) andfrom20to25min(phase2,inflammatory)afterformalin injec-tion (Hunskaar &Hole, 1987).Themice (n=6 per group) were thentreatedwithPLS(60mg/kg,i.p.)orsterilesaline(0.9%)30min beforeformalininjection.Morphine(5mg/kg,s.c.)wasalso admin-istered30minbeforeformalininjectionandusedasareference compound.

2.12. Hot-platetest

Thehotplatetestisanothercommonlyusedmethodtomeasure analgesicactivity(Eddy&Leinback,1953).Eachmousewasplaced twiceontoaheatedplate(51±1◦C),separatedbya30-min

inter-val.Thefirsttrialfamiliarizedtheanimalwiththetestprocedure, andthesecondtrialservedasthecontrolforthereactiontime (lick-ingthepaworjumping).Animalsshowingareactiontimegreater than20swereexcluded.Afterthesecondtrial(controlreaction time),groupsofanimals(n=6)receivedsterilesaline(0.9%,i.p.), PLS(60mg/kg,i.p.),ormorphine(5mg/kg,s.c.;referencedrug).The reactiontimesweremeasuredattimezero(0time)andat30,60, 90,and120minafterthecompoundswereadministered,witha cut-offtimeof45stoavoidpawlesions.

2.13. Statisticalanalysis

Theresultsareshownasthemeans±S.E.M.Forthe

0 1 2 3 4 0.00

0.04 0.08

0.12 Sal

Cg

PLS 10 mg/kg + Cg PLS 30 mg/kg + Cg PLS 60 mg/kg + Cg Indo 10 mg/kg + Cg

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

A

Time (h)

Change in volume (ml)

0 1 2 3 4

0.00 0.02 0.04 0.06 0.08

Sal Dxt

PLS 60 mg/kg + Dx Indo 10 mg/kg + Dx

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

B

Time (h)

Change in volume (ml)

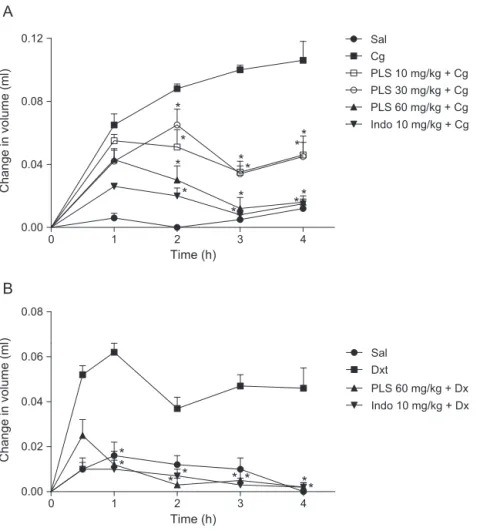

Fig.2.EffectofPLSfromD.simplexonpawedemainducedbycarragenan(A)anddextran(B).Pawedemawasinducedbycarragenan(Cg:500g/paw;PanelA)ordextran (Dx:500g/paw;PanelB)injectionsintotheplantarsurfaceoftherightpaw.Thechangeinpawvolumewasmeasuredattheindicatedtimeintervals.Miceweretreated withpolysaccharide(PLS:10,30and60mg/kg;i.p.)andindomethacin(Indo:10mg/kg,i.p.;positivecontrol).Thevaluesgivenaremeans±S.E.M.(n=6).*Statisticaldifference (p<0.05)comparedtocarragenan(PanelA)ordextran(PanelB)(one-wayANOVAfollowedbyNewman–Keulspost-test).

3. Resultsanddiscussion

3.1. StructuralanalysisofthePLSfromD.simplex

TheFT-IRspectrumofsolublepolysaccharidefromD.simplex

isdepictedinFig.1A.Thebandsintheregionof1400–700cm−1

arecharacteristicofagarocolloids(Chopin&Whalen,1993;Lahaye &Yaphe,1988;Maciel etal., 2008;Melo, Feitosa,Freitas, &de Paula,2002;Mollet,Rahaoui,&Lemoine,1998;Prado-Fernandez, Rodriguez-Vazquez, Tojo, & Andrade, 2003; Rochas, Lahaye, & Yaphe,1986).Thebandat1253and931cm−1canbeattributed

to the S O vibration of the sulphate groups C O C of 3,6-anhydrogalactoserespectively.Theregionat800–850cm−1isused

for algal polysaccharides to characterize the sulfate pattern of agarocolloids.Thepresenceofthelowintensitybandsat850and 820cm−1maysuggestasmalldegreeofsulfatesubstitutionatC-4

andC-6ofgalactose.

Theanomericregionof13CNMR(Fig.1B)showstwomain

sig-nals,whichwereassignedbasedonliteraturedata(Lahaye,Yaphe, Viet&Rochas,1989;Miller&Furneaux,1997;Usov,Yarotsky& Shashkov,1980; Valiente, Fernandez,Perez, Marquina,&Velez, 1992)asC-1of-d-galactoselinkedto3,6-␣-l-anhydrogalactose

atı102.6andC-1of3,6-anhydro-␣-l-galactopyranoseatı98.4.

ADEPT135◦ experimentwasusedtoinvestigatethepresenceof

CH2groups,consideringthatthepulsesequencesignalsofthe

car-bonsbearingtwoprotonshaveoppositeamplitudetotheCHand CH3carbons.TheDEPT135◦spectrumofD.simplex(Fig.1C)shows

twointenseCH2 signals atı61.5andı69.5attributedtoC-6of

-d-galactose and 3,6-␣-l-anhydrogalactose, respectively. The

lowerintenseCH2 signalobservedatı65.7maybeattributedas

C-6of␣-l-galactose-6sulfate.

Thetwelvemainsignalsobservedinthe13CNMRspectrumcan

beattributedbasedintheliteraturedata(Lahayeetal.,1989;Maciel etal.,2008;Meloetal.,2002;Miller&Furneaux,1997;Usovetal., 1980;Valienteetal.,1992)toC-1–C-6of-d-galactose(102.5,70.3,

82.3,68.9,75.5and61.5)andof3,6-␣-l-anhydrogalactose(98.4,

69.9,80.2,77.4,75.7and69.5).

The13C-NMRandFT-IRspectraindicatethatthemain

polysac-charide fraction extracted from D. simplex is a agarocolloid, corroboratingwithpreviousstudies(El-Sayed,1983;Tomodaetal., 1972).

3.2. Theanti-inflammatoryactivityofPLSonpawedemainduced bycarrageenananddextran

SincePLSderivedfromalgaerepresentanimportantcandidate therapeuticforthetreatmentofinflammation(Chen,Wu,&Wen, 2008;Groth,Grunewald,&Alban,2009),theanti-inflammatory activityofPLSextractedfromD.simplexwasassessedusing clas-sical experimental models of inflammation. Fig. 2 summarizes theeffectsofPLSonpawedemainexperimentalanimals. Treat-mentofmicewithcarrageenan(500g/paw;PanelA)ordextran (500g/paw;PanelB)inducedasignificantincreaseinpawvolume

thefourthhourafterinflammagenadministration(p<0.05).The maximumeffect induced byPLSadministration at dosesof 10, 30and60mg/kgwasobservedatthethirdhour,withinhibition rates of65.0%, 66.0% and 87.5%,respectively, compared to ani-malsthatreceivedcarrageenanalone.TheinhibitoryeffectofPLS onpawedemainducedbycarrageenanwasdose-dependent.The mosteffectivedosewas60mg/kgandthisdosewasthuschosenfor furtherevaluation,includingthatofitseffectsondextran-induced pawedema.WesubsequentlyobservedthatPLSalsoinhibitedthe edemainducedbydextran.Aninhibitionrateof80.6%wasobserved afterthefirsthour,comparedtothefindingobservedinthe con-trolgroup treated withdextranalone. The anti-oedematogenic effect of PLS against dextran-induced inflammation was main-taineduntilthefourthhourofanalysisinwhichtheedemawas almostcompletelyabsent(95.6%inhibition).Itiswell-documented thatinflammatoryeventstriggeredbydextranadministrationlead todevelopmentof edemaviaresident celldegranulation,while thoseinducedbycarrageenaninvolvecellmigration(Lo,Almeida, &Beaven,1982).Ourdataareinagreementwiththoseofother studiesinwhichanti-inflammatoryeffectsofPLSextractedfrom seaweedagainstcarrageenan-or dextran-inducedinflammation were reported (Chaves et al., 2013; Damasceno et al., 2013). Furthermore,PLS(60mg/kg)wasasefficaciousasindomethacin (p>0.05),acommercialdrugusedasananti-inflammatoryagent, reinforcingthepharmacologicpotentialofPLSextractedfromthis algalspecies.

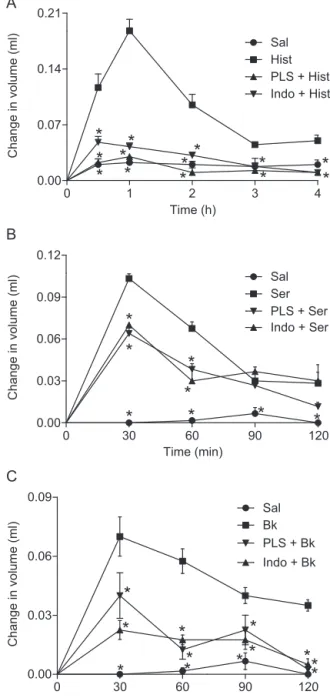

3.3. EffectofPLSonpawedemainducedbyvariousinflammagens

Comparedtoinjectionofthesalinecontrol,theinjectionof var-iousinflammagensintothesubplantarsurfaceofmousehindpaws producedamarkedincreaseinpawvolume(p<0.05)(Fig.3).The injectionof PLS(60mg/kg, i.p.)significantly reducedtheedema induced byphlogistic agents during alltested time courses.At 30min,thetimepointofthepeakeffectofthetestedagents,the edemavolumeinthePLSgroupwas0.022±0.004mLcomparedto

0.117±0.017mLinthehistaminegroup,correspondingto80.7%

inhibition (Fig.3A).PLSwasmore effectivethan indomethacin, which produced only a 58.9% inhibition. PLS also significantly inhibitedtheincreaseinpawvolumeofanimalstreatedwith sero-toninorbradykininby38.0%and42.8%,respectively(Fig.3BandC). Itiswellknownthatchemicalmediatorsincludinghistamine, sero-tonin,and bradykininareinvolved incarrageenan-induced paw edema(Chen,Tsai,&Wu,1995;Vinegaretal.,1987).Inthismodel, theedema isbelievedtobebiphasic,withthefirstphasebeing mediatedbythereleaseofhistamineandserotonin,followedbythe subsequentreleaseofbradykininandthelateedemaphasebeing dependentoncytokineproductionbyresidentcellsandneutrophil infiltration(Barbosaetal.,2009;Kulkarni,Mehta,&Kunchandy, 1986; Vinegar, Schreiber, & Hugo, 1969). In contrast, dextran-inducedpawedemaismediatedbyincreasedvascularpermeability inducedby mast celldegranulation of histamine andserotonin (Metcalfe, 2008).Theoedematousfluid formedbecauseof dex-traninjectioncontainslittleproteinandfewneutrophils(Gupta etal.,2003).Therefore,wecaninferthattheanti-oedematogenic actionofPLSmaybebecauseofthedifferentialinhibitionofspecific inflammatorymediatorsandmodulationofneutrophilinfiltration intheinflamedplantartissue.

3.4. EffectofPLSoncarrageenan-inducedMPOactivityinmouse pawtissue

AsshowninFig.4A,at4haftertreatmentwithinflammatory stimuli,a significantincrease inMPOactivitywasfoundinthe carrageenan-treatedanimals(15.23±3.45UMPO/mgplantar

tis-sue)comparedtothosetreatedwithsaline(0.68±0.11UMPO/mg

A

0 1 2 3 4

0.00 0.07 0.14 0.21

Sal Hist PLS + Hist Indo + Hist

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Time (h)

Change in volume (ml)

B

0 30 60 90 120

0.00 0.03 0.06 0.09 0.12

Sal Ser PLS + Ser Indo + Ser

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Time (min)

Change in volume (ml)

C

0 30 60 90 120

0.00 0.03 0.06 0.09

Sal Bk PLS + Bk

Indo + Bk

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Time (min)

Change in volume (ml)

Fig.3.EffectofPLSfromD.simplexonpawedemainducedbyvarious inflamma-gens.Pawedemawasinducedby(A)histamine(Hist:500gperpaw),(B)serotonin (Ser:500gperpaw),or(C)bradykinin(Bk:6nmol,w/v,perpaw)injectionsintothe plantarsurfaceoftherightpaw.Thechangeinpawvolumewasmeasuredatthe indi-catedtimeintervals.Animalswerepretreatedwithpolysaccharide(PLS:60mg/kg; i.p.)andindomethacin(Indo:10mg/kg,i.p.)wasusedasapositivecontrol.The valuesgivenaremeans±S.E.M.(n=5).*Statisticaldifference(p<0.05)compared toinflammatorystimulitreatment(one-wayANOVAfollowedbyNewman–Keuls post-test).

plantar tissue). Pre-treatment withPLS (60mg/kg) consistently reducedMPOactivityinpawtissue(4.17±0.71UMPO/mgof

tis-sue);theeffectwassimilartothatofindomethacin(5.03±1.48

A

Sal - PLS Indo

0 5 10 15

20 #

*

*

Carrageenan (500 g per paw)

UMPO/mg of tissue

B

C

Sal - PLS Indo

0 2000 4000 6000 8000

10000 #

*

*

Carrageenan (500 g/cavity)

Total leucocytes × 10

3 ml/cavity

Sal - PLS Indo

0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000

#

*

*

Carrageenan (500 g/cavity)

Neutrophils × 10

3ml/cavity

Fig.4.TheeffectsofPLSfromD.simplexonmyeloperoxidase(MPO)activityinpawtissueandcellmigrationintheperitonealcavity.Animalsreceived polysaccha-ride(PLS:60mg/kg;i.p.)30minbeforecarrageenanadministration,andmyeloperoxidaseactivityorneutrophilmigrationwereevaluated4hlater.Thevaluesgivenare means±S.E.M.(n=5).Indomethacin(Indo:10mg/kg,i.p.)wasusedasapositivecontrol.#p<0.05vs.salinegroup;*p<0.05vs.carrageenangroup(one-wayANOVAfollowed

byNewman–Keulspost-test).

3.5. Anti-inflammatoryeffectofPLSoncarrageenan-induced peritonitisinmice

The hypothesis that the anti-oedematogenic effect of PLS againstcarrageenan-inducedinflammationwasrelatedtoa reduc-tion in neutrophil infiltration to the site of inflammation was

further investigated in an experimental mouse model of peri-tonitis. This model allows quantification of cells and levels of several inflammatory mediators and is a well-characterized pharmacological tool for theexamination of neutrophil migra-tion(Montanher,Zucolotto,Schenkel,&Fröde,2007).Compared to the animals treated with saline alone, those treated with

A

B

Sal

-

PLS

Indo

0

500

1000

1500

*

*

#

Carrageenan (500 g/cavity)

(pg /ml)

Sal - PLS Indo

0 200 400 600 800

#

*

*

Carrageenan (500 g/cavity)

(pg/ml)

Fig.5. EffectofPLSfromD.simplexoncarrageenan-inducedcytokineproductioninperitonitis.Animalswereinjectedwithpolysaccharide(PLS:60mg/kg)30minbefore carrageenanadministration,and4hlaterthelevelsofIL-1(A)andTNF-␣(B)weremeasuredintheperitonealfluid.Thevaluesgivenaremeans±S.E.M.(n=5).Indomethacin (Indo:10mg/kg)wasusedasapositivecontrolforanti-inflammatoryactivity.#,*Statisticaldifference(p<0.05)comparedtosalineandcarrageenan,respectively(one-way

Table1

AntinociceptiveeffectofPLSfromD.simplexonaceticacidinducedwrithes.

Treatment Dose

(mg/kg)

Numberofabdominal constrictions(20min)

Inhibition(%)

Control(aceticacid) – 47.0±5.6 –

Morphine 5 0.0±0.0a 100

PLS 60 10.8±3.6a 77.0

Valuesaregivenasthemeans±S.E.M.offiveanimals,asanalyzedbyone-way

ANOVAfollowedbyNewman–Keulstest(p<0.05).PLS:sulphatedpolysaccharides fraction.

aComparedwithaceticacidcontrolgroup.

intraperitoneal administration of carrageenan showed a sig-nificant increase in total leukocyte and neutrophil counts in the peritoneal fluid (1525±185.4×103 total leukocytes/mL

vs. 9050±429.1×103 total leukocytes/mL; 370.6±42.9×103

neutrophils/mL vs. 7789±459.1×103 neutrophils/mL; p<0.05) (Fig. 4B and C). Pre-treating theanimals with 60mg/kg of PLS reduced the total leukocyte (4913±668.4×103cells/mL) and

neutrophilmigration(3804±1228×103cells/mL)tolevels

com-parableto thecorresponding levelsobserved in the salineand indomethacingroups(p>0.05).

3.6. EffectofthePLSfractiononcarrageenan-inducedcytokine productioninperitonealexudates

Theinflammatoryresponseinducedbycarrageenaninthe peri-tonitismodelwasassociatedwithanincreaseinthelevelsofIL1-

andTNF-␣(Fig.5AandB).ThelevelsofIL1-andTNF-␣inthe per-itonealfluidofthesalinecontrolgroupwere155.4±19.7pg/mL

and 249.5±91.5pg/mL, respectively; the corresponding levels

were higher in the carrageenan-treated animals (IL1- level: 1187±39.8pg/mL and TNF-␣ level: 564.9±52.3pg/mL).

Car-rageenaninducesneutrophilmigrationintotheperitonealcavity through an indirect mechanism that involvesthe activation of macrophagesandreleaseofpro-inflammatorycytokines,suchas IL-1 and TNF-␣ (Lo et al., 1982). Such increases in cytokine levels might result in plasma protein extravasation and cel-lular infiltration into the site of inflammation (Rosenbaum & Boney,1991;Thorlacius,Lindbom,&Raud1997).Inthepresent study, compared to the carrageenan-treated group, the PLS-treated animals exhibited a significant reduction of both IL1-

andTNF-␣levelsinperitonealexudates(330.9±45.1pg/mLand

81.1±4.3pg/mL, respectively) (p<0.05). TNF-␣ and IL-1 are potentpro-inflammatorycytokinesthatpossessmultipleeffects, includingtheactivationofinflammatorycells,inductionofseveral inflammatoryproteins, edemaformation,andneutrophil migra-tion(Haddad,2002;Hopkins,2003).Onthebasisofthisfinding, we propose thatPLS treatmentdecreased neutrophilmigration by decreasing the production and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

3.7. AntinociceptiveeffectofPLSonaceticacid-inducedwrithing

There is a strong association between the development of pain and the inflammatory process (Bitencourt et al., 2008). It was previously demonstrated that inhibition of neutrophil migrationreduceshypernociceptioninducedbydifferent inflam-matory stimuli (Hopkins, 2003; Tjølsen &Hole, 1997). Several reports havedemonstrated that PLSextractedfromalgae show promiseasantinociceptiveagents(Britoetal.,2013;Chavesetal., 2013; Damasceno et al., 2013). Thus, in thepresent study the

0 20 40 60 80

Sal Formalin PLS + Formalin Morphine +Formalin

1st Phase 2nd Phase

# #

*

*

*

*

Licking time (s)

A

0 30 60 90 120

0 10 20 30 40

Sal PLS Morphine

*

*

*

#

#

#

B

latency (s)

Fig.6. AntinociceptiveeffectofPLSfromD.simplexinformalin-inducedpawlicking(A)andhotplatetest(B).AnimalsreceivedPLS(60mg/kg,i.p.)ormorphine(5mg/kg, sc)30minbefore2.5%formalinadministrationbytheintraplantarroute.Lickingtimewasrecordedinthefirst5min(1stphase)andafter20min(2ndphase)during5min. InthehotplatetesttheanimalsreceivedthesamedosesofPLSormorphinetoevaluatedreactiontimestothermalstimuli.Thevaluesgivenaremeans±S.E.M.(n=6).Panel (A)#,*Statisticaldifference(p<0.05)comparedtosalineandformalin,respectively.Panel(B)*,#Statisticaldifference(p<0.05)comparedtosaline(one-wayANOVAfollowed

antinociceptive potentialof PLSfrom D. simplex wasalso eval-uated using three well-accepted murine pain models. Table 1

showstheantinociceptiveeffectofPLSonabdominalcontractions inducedbyaceticacid. Asexpected,morphineshowedapotent analgesicresponsecomparedtothatobservedincontrolanimals (p<0.05). Theadministration of PLS(60mg/kg)30minprior to painfulstimulisignificantlyreducedaceticacid-induced abdom-inal writhing (77.0% inhibition) compared to control (p<0.05). Thewrithing test is commonly used for screening peripherally activeanalgesiccompounds.Algogenicagents,suchasaceticacid, provokeastereotypicalbehaviorinmicecharacterizedby abdom-inalcontractions,movementsofthebodyasawhole,andtwisting ofdorsalabdominalmuscles(Bars,Gozariu,&Cadden,2001).This modelinvolvesdifferentnociceptivemechanisms,suchasrelease of biogenic amines (histamine and serotonin), bradykinin, and PGE2(Collieret al.,1968; Duarte,Nakamura, &Ferreira,1988). Furthermore,itiswellestablishedthatthenociceptiveresponse causedby aceticacidisalsodependentontherelease ofsome cytokines,suchasTNF-␣andIL-1viamodulationofmacrophages and mastcells localized totheperitonealcavity (Ribeiroet al., 2000).Thus,PLSmayreducewrithingbyinhibitionoftherelease ofnociceptivemediatorsinresponsetoaceticacid.

3.8. EffectofPLSintheformalintest

Fig.6Ashowsthatintraplantarinjectionofformalin(2.5%/paw) significantlyincreasedthetotallickingtimeinthefirstand sec-ondphases compared to salinetreatment(p>0.05).This event wasstronglyinhibitedinbothphasesbypre-treatmentwiththe PLSfraction(60mg/kg).Weobservedthatthelickingtimeof PLS-treatedanimalswasinhibitedby60.5%and61.7%inthefirstand secondphases,respectively, comparedtothefindings observed in theformalin group. The inhibitoryeffect of PLS wassimilar tothat seen in the morphine group (Firstand secondphases). Formalin-inducedpersistent pain in mouse paws involves two distinctphases.Thefirstphase (neurogenic)ischaracterizedby directchemicalstimulationofnociceptors,andthesecondphaseis accompaniedbythereleaseofinflammatorymediators,such neu-ropeptides,prostaglandins,serotonin,histamine,and bradykinin (Hunskaaretal.,1985;Hunskaar&Hole,1987;Murray,Porreca, &Cowan,1988).SincePLSexhibitedactivityinbothphases,itis suspectedthatitactscentrally,andapossibleinteractionwith opi-oidreceptorsisalsoindicated(Shibata,Ohkubo,Takahashi,&Inoki, 1989).

3.9. EffectofPLSinthehotplatetest

TheeffectofintraperitonealadministrationofPLS(60mg/kg) onanimalsevaluatedinthehotplatetestvariedaccordingtothe observationtimeused(Fig.6B).Attimezeroand120min,no sig-nificantantinociceptiveeffectwasobservedcomparedtocontrols (p>0.05).At30,60,and90min,PLSincreasedthereactiontimesof miceby34.4%,122.9%,and160.5%,respectively.Thereferencedrug morphine,anopioidreceptoragonist,inducedasignificantincrease inlatency,asexpected.Thehot-platetestisawell-knownmodel foracutethermalnociception.Increasesinreactiontimeindicate analgesiceffectsviasupraspinalandspinalreceptors(Nemirovsky, Chen,Zelman,&Jurna,2001).Furthermore,thetestspecifically helps evaluatecentral nociception (Vilela, Padilha, DosSantos, Silva,&Paiva,2009)andmeasurecomplexresponsesto inflam-mationand nociception promotedby opioid agents (Bhandare, Kshirsagar,Vyawahare,Hadambar,&Thorve,2010).Onthebasis ofourresults,weconcludedthatPLScaninhibitnociceptionby eitherperipheralorcentralmechanisms.

References

Barbosa,A.L.,Pinheiro,C.A.,Oliveira,G.J.,Moraes,M.O.,Ribeiro,R.A.,Vale,M.L., etal.(2009).Tumorbearingdecreasessystemicacuteinflammationinrats-role ofmastcelldegranulation.InflammationResearcher,58,235–240.

Bars,D.,Gozariu,M.,&Cadden,S.W.(2001).Animalmodelsofnociception.

Phar-macologicalReviews,53,597–652.

Bhandare,A.M.,Kshirsagar,A.D.,Vyawahare,N.S.,Hadambar,A.A.,&Thorve,V. S.(2010).Potentialanalgesic,anti-inflammatoryandantioxidantactivitiesof hydroalcoholicextractofArecacatechuL.nut.FoodandChemicalToxicology,48, 3412–3417.

Bitencourt,F.S.,Figueiredo,J.G.,Mota,M.R.L.,Bezerra,C.C.R.,Silvestre,P.P.,Vale, M.R.,etal.(2008).Antinociceptiveandanti-inflammatoryeffectsofa mucin-bindingagglutininisolatedfromtheredmarinealgaHypneacervicornis.

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’sArchivesofPharmacology,377,139–148.

Bradley,P.P.,Priebat,D.A.,Christensen,R.D.,&Rothstein,G.(1982).Measurement ofcutaneousinflammation:Estimationofneutrophilcontentwithanenzyme marker.JournalofInvestigativeDermatology,78,206–209.

Brito,T.V.,Prudêncio,R.S.,Sales,A.B.,Júnior,F.C.V.,Candeira,S.J.N.,Franco,A. X.,etal.(2013).Anti-inflammatoryeffectofsulfacted-polyssacaridefractionof extractedfromredAlgaeHypneamusciformisviathesuppressionneutrophil migrationbyNOsignalingpathway.JournalofPharmacyandPharmacology,65, 724–733.

Cabrita,M.T.,Vale,C.,&Rauter,A.P.(2010).Halogenatedcompoundsfrommarine algae.MarineDrugs,8,2301–2317.

Carvalho,J.T.C.,Teixeira,J.R.M.,Souza,P.J.C.,Bastos,J.K.,Filho,D.S.,&Sarti,S. J.(1996).Preliminarystudiesofanalgesicandanti-inflammatorypropertiesof

Caesalpineaferreacrudeextract.JournalofEthnopharmacology,53,175–178.

Chaves,L.S.,Nicolau,L.A.D.,SILVA,R.O.,Barros,F.C.N.,Freitas,A.L.P.,Aragão,K.S., etal.(2013).Anti-inflammatoryandantinociceptiveeffectsinmiceofasulfated polysaccharidefractionextractedfromthemarineredalgaeGracilariacaudata.

ImmunopharmacologyandImmunotoxicology,35,93–100.

Chen,D.,Wu,X.Z.,&Wen,Z.Y.(2008).Sulfatedpolysaccharidesandimmune response:Promoterorinhibitor?PanminervaMedica,50,177–183.

Chen,Y.F.,Tsai,H.Y.,&Wu,T.S.(1995).Anti-inflammatoryandanalgesicactivities fromrootsofAngelicapubescens.PlantaMedica,61,2–8.

Chopin,T.,&Whalen,E.(1993).Anewandrapidmethodforcarrageenan identifi-cationbyFTIRdiffuse-reflectancespectroscopydirectlyondried,groundalgal material.CarbohydrateResearch,246,51–59.

Collier,H.O.J.,Dinneen,J.C.,Johnson,C.A.,&Schneider,C.(1968).The abdomi-nalconstrictionresponseanditssuppressionbyanalgesicdrugsinthemouse.

BritishJournalofPharmacologyandChemotherapy,32,295–310.

Cumashi,A.,Ushakova,N.A.,Preobrazhenskaya,M.E.,D’Incecco,A.,Piccoli,A., Totani,L.,etal.(2007).Acomparativestudyoftheanti-inflammatory, antico-agulant,antiangiogenic,andantiadhesiveactivitiesofninedifferentfucoidans frombrownseaweeds.Glycobiology,17,541–552.

Damasceno,S.R.B.,Rodrigues,J.C.,Silva,R.O.,Nicolau,L.A.D.,Chaves,L.S.,Freitas, A.L.P.,etal.(2013).RoleoftheNO/KATPpathwayintheprotectiveeffectof asulfatedpolysaccharidefractionfromthealgaeHypneamusciformisagainst ethanolinducedgastricdamageinmice.RevistaBrasileiradeFarmacognosia,23, 320–328.

DeSmet,P.A.(1997).Theroleofplant-deriveddrugsandherbalmedicinesin healthcare.Drugs,54,801–840.

Déciga-Campos,M.,Palacios-Espinosa,J.F.,Reyes-Ramírez,A.,&Mata,R.(2007).

Antinociceptiveand anti-infammatoryeffectsof compoundsisolatedfrom

ScaphyglottislividaandMaxillariadensa.JournalofEthnopharmacology,114,

161–168.

Duarte,I.D.G.,Nakamura,M.,&Ferreira,S.H.(1988).Participationofthe sympa-theticsysteminaceticacid-inducedwrithinginmice.BrazilianJournalofMedical

andBiologicalResearch,21,341–343.

Eddy,N.B.,&Leinback,D.(1953).Syntheticanalgesics.II.Dithienyl-butenyland dithienylbutylamines.JournalofPharmacologyandExperimentalTherapeutics, 107,385–393.

El-Sayed,M.M.(1983).PurificationandcharacterizationofagarfromDigenea

sim-plex.CarbohydrateResearch,118,119–126.

Groth,I.,Grunewald,N.,&Alban,S.(2009).Pharmacologicalprofilesofanimal-and nonanimal-derivedsulfatedpolysaccharides—Comparison of unfractionated heparin,thesemisyntheticglucansulfatePS3,andthesulfatedpolysaccharide fractionisolatedfromDelesseriasanguinea.Glycobiology,19,408–417.

Gupta,M.,Mazumdar,U.K.,Sivakumar,T.,Vamsi,M.L.,Karki,S.S.,Sambathkumar, R.,etal.(2003).Evaluationofanti-inflammatoryactivityofchloroformextract

ofBryonialaciniosainexperimentalanimalmodels.Biological&Pharmaceutical

Bulletin,26,1342–1344.

Haddad,J.J.(2002).Cytokinesandrelated-receptormediatedsignallingpathways.

BiochemicalandBiophysicalResearchCommunications,297,700–713.

Hajare,S.W.,Chandra,S.,Charma,J.,Tandan,S.K.,Lal,J.,&Telang,A.G.(2001).

Anti-inflammatoryactivityofDalbergiasissooleaves.Fitoterapia,72,131–139.

Hopkins,S.J.(2003).Thepathologicalroleofcytokines.LegalMedicine,5,45–47.

Hunskaar,S.,&Hole,K.(1987).Theformalintestinmice:Dissociationbetween inflammatoryandnon-inflammatorypain.Pain,30,103–104.

Hunskaar,S.,Fasmer,O.B.,&Hole,K.(1985).Formalintestinmice,ausefultechnique forevaluatingmildanalgesics.JournalofNeuroscienceMethods,14,69–76.

Iannitti,T.,&Palmieri,B.(2010).Anupdateonthetherapeuticroleofalkylglycerols.

MarineDrugs,8,2267–2300.

Koster,R.,Anderson,M.,&De-Beer,E.J.(1959).Aceticacidforanalgesicscreening.

Kulkarni,S.K.,Mehta,A.K.,&Kunchandy,J.(1986).Anti-inflammatoryactionsof clonidine,guanfacineandB-HT920againstvariousinflammagen-inducedacute pawoedemainrats.ArchivesInternationalesdePharmacodynamieetdeThérapie, 279,324–334.

Kusaykin,M.,Bakunina,I.,Sova,V.,Ermakova,S.,Kuznetsova,T.,Besednova,N.,etal. (2008).Structure,biologicalactivity,andenzymatictransformationoffucoidans fromthebrownseaweeds.BiotechnologyJournal,3,904–915.

Lahaye,M.,&Yaphe,W.(1988).Effectsofseasonsonthechemicalstructureandgel strengthofGracilariapseudoverrucosaagar(Gracilariales,Rhodophyta).

Carbo-hydratePolymers,8,285–301.

Lahaye,M.,Yaphe,W.,Viet,M.T.P.,&Rochas,C.(1989).13CNMRspectroscopic

investigationofmethylatedandchargedagaroseoligosaccharidesand polysac-charides.CarbohydrateResearch,190,249–265.

Lanhers,M.C.,Fleurentin,J.,Dorfman,P.,Mortier,F.,&Pelt,J.M.(1991).Analgesic, antipyreticandanti-inflammatorypropertiesofEuphorbiahirta.PlantaMedica, 57,225–231.

Linley,J.E.,Rose,K.,Ooi,L.,&Gamper,N.(2010).Understandinginflammatorypain: Ionchannelscontributingtoacuteandchronicnociception.EuropeanJournalof

Physiology,459,657–669.

Lo,T.N.,Almeida,A.P.,&Beaven,M.A.(1982).Dextranandcarrageeninevoke differ-entinflammatoryresponseinratwithrespecttocompositionofinfiltratesand effectofindomethacin.JournalofPharmacologyandExperimentalTherapeutics, 221,261–267.

Maciel,J.S.,Chaves,L.S.,Souza,B.W.S.,Teixeira,D.I.A.,freitas,A.L.P.,feitosa,J. P.A.,etal.(2008).Structuralcharacterizationofcoldextractedfractionof sol-ublesulfatedpolysaccharidefromRedSeaweedGracilariabirdiae.Carbohydrate

Polymers,71,559–565.

Mayer,A.M.S.,Glaser,K.B.,Cuevas,C.,Jacobs,R.S.,Kem,W.,Little,R.D.,etal.(2010).

Theodysseyofmarinepharmaceuticals:Acurrentpipelineperspective.Trends

inPharmacologicalSciences,31,255–265.

Melo,M.R.S.,Feitosa,J.P.A.,Freitas,A.L.P.,&dePaula,R.C.M.(2002).Isolation andCharacterizationofsolublesulfatedpolysaccharidefromtheRedSeaweed

Gracilariacornea.CarbohydratePolymers,49,491–498.

Metcalfe,D.D.(2008).Mastcellsandmastocytosis.Blood,15,946–956.

Miller,I.J.,&Furneaux,R.H.(1997).Thestructuraldeterminationoftheagaroid polysaccharidefromfourNewZealandalgaeintheorderCeramialesbymeans ofC-13NMRspectroscopy.BotanicaMarina,40,333–339.

Mollet,J.-C.,Rahaoui,A.,&Lemoine,Y.(1998).Yield,chemicalcompositionandgel strenghofagarocolloidsofGracilariagracilis,Gracilariopsislongissimaandthe newlyreportedGracilariacf.vermiculophyllafromRoscoff(Brittany,France).

JournalofAppliedPhycology,10,59–66.

Moncada,S.,&Higgs,A.(1993).Thel-arginine-nitricoxidepathway.TheNewEngland

JournalofMedicine,329,2002–2012.

Montanher,A.B.,Zucolotto,S.M.,Schenkel,E.P.,&Fröde,T.S.(2007).Evidenceof anti-inflammatoryeffectsofPassifloraedulisinaninflammationmodel.Journal

ofEthnopharmacology,109,281–288.

Murray,C.W.,Porreca,F.,&Cowan,A.(1988).Methodologicalrefinementstothe mousepawformalintest.Ananimalmodeloftonicpain.Journalof

Pharmaco-logicalMethods,20,175–186.

Nemirovsky,A.,Chen,L.,Zelman,V.,&Jurna,I.(2001).Theantinociceptiveeffectof thecombinationofspinalmorphinewithsystemicmorphineorbuprenorphine.

AnesthesiologyAnalgesic,93,197–203.

Prado-Fernandez,J.,Rodriguez-Vazquez,J.A.,Tojo,E.,&Andrade,J.M.(2003). Quan-titationof-,-and-carrageenansbymid-infraredspectroscopyandPLS regression.AnalyticaChimicaActa,480,23–37.

Ribeiro,R.A.,Vale,M.L.,Thomazzi,S.M.,Paschoalato,A.B.,Poole,S.,Ferreira,S.H., etal.(2000).Involvementofresidentmacrophagesandmastcellsinthewrithing nociceptiveresponseinducedbyzymosanandaceticacidinmice.European

JournalofPharmacology,387,111–118.

Rochas,C.,Lahaye,M.,&Yaphe,W.(1986).Sulfatecontentofcarrageenanandagar determinedbyInfraredSpectroscopy.BotanicaMarina,29,335–340.

Rosenbaum,J.T.,&Boney,R.S.(1991).Useofasolubleinterleukin-1receptorto inhibitocularinflammation.CurrentEyeResearch,10,1137–1139.

Shibata,M.,Ohkubo,T.,Takahashi,H.,&Inoki,R.(1989).Modifiedformalintest: Characteristicbiphasicpainresponse.Pain,38,347–352.

Silva,J.S.E.,Moura,M.D.,Oliveira,R.A.G.,Diniz,M.F.F.M.,&Barbosa-Filho,J. M.(2003).Naturalproductsinhibitorsofovarianneoplasia.Phytomedicine,10, 221–232.

Silva,R.O.,Santos,G.M.P.,Nicolau,L.A.D.,Lucetti,L.T.,Santana,A.P.M.,Chaves,L.S., etal.(2011).Sulfated-polysaccharidefractionfromredalgaeGracilariacaudate protectsmicegutagainstethanol-induceddamage.MarineDrugs,9,2188–2200.

Souza,G.E.,Cunha,F.Q.,Mello,R.,&Ferreira,S.H.(1988).Neutrophilmigration inducedbyinflammatorystimuliisreducedbymacrophagedepletion.Agents

Actions,24,377–380.

Srinivasan,K.,Muruganandan,S.,Lal,J.,Chandra,S.,Tandan,S.K.,&Prakash,V.R. (2001).Evaluationofanti-inflammatoryactivityofPongamiapinnataleavesin rats.JournalofEthnopharmacology,78,151–157.

Takano, R.,Shiomoto, K., Kamei, K.,Hara, S.,& Hirase,S.(2003).Occurrence of carrageenan structurein an agarfrom the Red SeaweedDigenea sim-plex(Wulfen)C.agardh(Rhodomelaceae,Ceramiales)withashortreviewof Carrageenan–AgarocolloidhybridintheFlorideophycidae.BotanicaMarina,46, 142–150.

Thorlacius,H.,Lindbom,L.,&Raud,J.(1997).Cytokine-inducedleukocyterollingin mousecremastermusclearteriolesinP-selectindependent.AmericanJournalof

Physiology,272,1725–1729.

Tjølsen,A.,&Hole,K.(1997).Animalmodelsofanalgesia.InA.Dickenson,&J.Besson (Eds.),Thepharmacologyofpain(130)(pp.1–20).SpringerVerlag.

Tomoda,M.,Nakatsuka,S.,&Minami,E.(1972).Plantmucilages.IV.Mainstructural featuresofthemucouspolysaccharideisolatedfromDigeneasimplex.Chemical

andPharmaceuticalBulletin,20,953–957.

Usov,A.I.,Yarotsky,S.V.,&Shashkov,A.S.(1980).13C-NMRspectroscopyofred

algalgalactans.Biopolymers,19,977–990.

Valiente,O.,Fernandez,L.E.,Perez,R.M.,Marquina,G.,&Velez,H.(1992).Agar PolysaccharidesfromRedSeaweedsGracilariadomingensisSonderexKutzing

andGracilariamammilaris(Montagne)Howe.BotanicaMarina,35,77–81.

Vilela,F.C.,Padilha,M.M.,DosSantos-E-Silva,L.,Alves-da-Silva,G.,&Giusti-Paiva,A. (2009).EvaluationoftheantinociceptiveactivityofextractsofSonchusoleraceus L.inmice.JournalofEthnopharmacology,124,306–310.

Vinegar,R.,Schreiber,W.,&Hugo,R.(1969).Biphasicdevelopmentofcarrageenan edemain rat. Journalof Pharmacology andExperimental Therapeutics, 166, 96–103.

Vinegar,R.,Truax,J.F.,Selph,J.L.,Johnston,P.R.,Venable,A.L.,&McKenzie,K.K. (1987).Pathwaytocarrageenaninducedinflammationinthehindlimbofthe

rat.FederationProceedings,46,118–126.

Wijesekara,I.,Pangestuti,R.,&Kim,S.K.(2010).Biologicalactivitiesandpotential healthbenefitsofsulfatedpolysaccharidesderivedfrommarinealgae.

Carbohy-dratePolymers,11,14–21.

Winter,C.A.,Risley,E.A.,&Nuss,G.W.(1962).Carrageenin-inducededemainhind pawoftheratasanassayforanti-inflammatorydrugs.ProceedingsoftheSociety