SALMONELLA ENTEROCOLITIS: REPORT OF A LARGE

FOODBORNE OUTBREAK IN TRUJILLO, PERU’

Robert A. Gunn* and Felix Bullh Loarte”

On 5 May 1977 food contaminated with Salmonella thompson

(Group Cl) hosfiitalized 545 university students in Trujillo, Peru. Prom@ investigation pinpointed the responsible orga- nism, the most likely source of contamination, and a number

of poor food-handling practices that may have contributed to the event. The report of the investigation, presented here, pro- vides a meful illustration of international epidemiologic coop- eration and points out a number of measures that can help prevent foodborne disease outbreaks of this kind.

Introduction

Salmonella

food poisoning, though gen- erally not life-threatening, can cause severe illness. Moreover, an outbreak affecting many individuals can overtax medical re- sources, creating a community-wide medi- cal emergency. This report describes an outbreak ofSalmonella

food poisoning, probably caused by faulty food-handling procedures, in which 545 students were hospitalized and community medical serv- ices were temporarily overloaded. Epide- miologic methods used to investigate the outbreak are discussed, and correctable food-handling practices that could have contributed to the event are pointed out.Background

On 6 May 1977 the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) was informed

lAls0 appearing in Spanish in the Boletfn de la Oficina Sanitaria Pana&icana, 1979.

%acterial Diseases Division, Bureau of Epidemiol- ogy, Center for Disease Control, Public Health Serv- ice, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Wel- fare, Atlanta, Georgia 30333.

3Department of Communicable Disease Eradication and Control, Ministry of Health, Lima, Peru.

of a large outbreak of acute illness among university students in Trujillo, Peru. Initially-because some of the students complained of diplopia and weakness, and because neurologic examinations revealed decreased reflexes and pupillary abnormal- ities-botulism was suspected and PAHO assistance was requested. Later that same day, a PAHO epidemiologic consultant from the U.S. Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia, departed for Trujillo to evaluate the situation and to hand-carry botulinal antitoxin to the area.

Upon arrival he learned that 545 Uni- versity of Trujillo students had been admit- ted to three hospitals between the evening of 5 May and 9:00 a.m. on 7 May with acute gastrointestinal symptoms. The neu- rologic signs and symptoms initially ob- served in some patients had resolved, and botulism was no longer considered a likely diagnosis. Stool specimens obtained from 40 patients were processed at the laboratory of the Microbiology Department of the Tru- jillo University Medical School. The labo- ratory reported isolation of

Salmonella

Group Cl organisms from all 40 specimens. Thereupon an investigation to determine the vehicle of infection and method of con- tamination was begun.Investigation

The Setting

The University of Trujillo, composed of many colleges scattered about the city, has a student population of approximately 7,000. Some students with limited finances from outlying areas live in rooming houses in the city and are served three meals a day at a special university dining hall. At the time of this investigation only 640 students ate regularly at the dining hall; other students ate at home or in nearby restau- rants.

Methods

For purposes of this investigation, a case was defined as an occurrence of acute diar- rhea1 illness in a student hospitalized on 5, 6, or 7 May for treatment of that illness. A questionnaire was prepared requesting in- formation about the symptoms of individ- ual patients and about food consumed on 5 May (the 24-hour period preceding onset of most cases). On 8 May the questionnaire was distributed to patients at BelCn Hospi- tal, one of the three hospitals that received the students. Also, in an attempt to question students who had eaten at the dining hall on 5 May but had remained well, the same questionnaire was given to students entering the dining hall for lunch on Monday, 9 May. *In addition on 9 May, the question- naire was administered to 25 of the 40 kitch- en employees working at the dining hall.

A case-control study of 5 May food con- sumption and illness was then performed. Questionnaire results obtained from con- trols (students who reported no illness but ate at the dining hall on 5 May) were com- pared with questionnaire results obtained from students with cases of diarrhea admit- ted to hospital. The two groups (cases and controls) were treated as nonrandom sam- ples of ill and well students. No data were requested regarding the amount of each

food eaten or the exact time it was con- sumed.

In the forementioned laboratory study, 40 specimens were plated directly onto Mac- Conkey’s and deoxycholate agar and ino- culated into tetrathionate broth. Suspect colonies were subcultured on triple sugar urea (TSU) slants; standard

Salmonella

polyvalent and group-specific antisera were used for group identification.Also, rectal swabs placed in Cary-Blair media were obtained on 8 May from 30 pa- tients at the Regional Hospital (another of the three that received the students) and 10 patients at Belen Hospital. The next day these were sent by air transport to the Na- tional Enterobacteria Reference Depart- ment, National Institute of Health, Lima, Peru. In addition, 10 isolates of

Salmonella

Group Cl obtained from stool specimens processed by the Trujillo University of Microbiology were sent to the National Enterobacteria Reference Department in Lima and to the Epidemiologic Laboratory Investigation Branch, Bacterial Diseases Division, Bureau of Epidemiology, U.S. Center for Disease Control in Atlanta, Georgia, for serotyping.Finally, an environmental study was per- formed that included inspection of the dining hall and questioning of food han- dlers regarding food preparation. Swabs from surfaces, feces-soiled eggs, and whole eggs were obtained; and rectal swabs were taken from two food handlers who prepared the implicated food item.

Results

Seventy-nine patients at Belgn Hospital returned questionnaires indicating their symptoms. Of these patients, 77 (97%) . reported fever, 76 (96%) diarrhea, 75 (9570) myalgia, 68 (860J0) chills, 66 (8470) head- ache, 52 (66’%) abdominal cramps, and 43 (54%) vomiting. Bloody stools were reported by one patient.

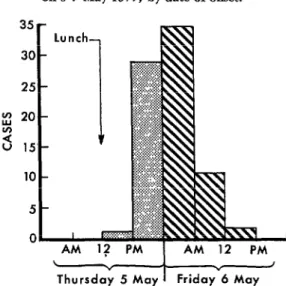

dining hall on 9 May identified 27 students who had eaten in the dining hall on 5 May without becoming ill, as well as an addi- tional 53 students who had become ill but had not been hospitalized. Of the 640 students who regularly ate in the dining hall, 598 (93%) had become ill, 27 (4%) had remained well, and the health status of 15 (3%) was unknown. The epidemic curve for the 79 hospitalized patients completing questionnaires, based on the time of onset of illness, is shown in Figure 1. The incuba- tion period had a mean length of 13.4 hours, a median of 14 hours, and a range of 6-24 hours. The duration of illness was not determined; however, three days after the peak of the outbreak only 40 (7%) of the 545 admitted patients remained hospitalized.

When the case-control questionnaire data from the 27 well students and the 79 hospi- talized students were analyzed (see Table l), a significant difference was found in the frequency with which ill and well students had eaten sardine-mayonnaise salad (p < .OOOOOl, Fisher’s exact test). Analysis of the questionnaire and interview data from 25 employees (Table 2) also showed that ill

Figure 1. Cases of salmonellosis among patients admitted to B&n Hospital (Tmjillo, Peru)

on 5-7 May 1977, by date of onset.

35

Lunch 30

E 1

m;,:s

. . . ..t'(..)

Ir :::,::.::$+

25 :::,:::::::.: ::x,:.;

Thursda;

employees were significantly more likely to have eaten the sardine-mayonnaise salad (p= .02, Fisher’s exact test). None of the food handlers questioned reported an intes- tinal illness during the preceding week (28 April-5 May).

The sardine-mayonnaise salad had been prepared between lo:30 and 11:00 a.m. on 5 May from 64 cans of sardines, four dozen raw eggs, potatoes, salt, pepper, and vege- table oil. The eggs, which had been received directly from a local farm on 4 May, had not been refrigerated. Many remaining eggs from the same batch used in the salad were soiled with feces. The eggs, potatoes, oil, salt, and pepper had been mixed in a large metal pot, and the sardines had been added to the mixture. The salad had then been placed on individual plates and sent on trays to the upstairs serving area, where the trays had been placed in a refrigerator.

Since the refrigeration unit did not operate 24 hours a day, being turned on only at about 11:OO a.m. on days when cold foods were being served, it is doubtful that appropriate refrigeration temperatures (7%, 45OF) had been attained. There was no functioning temperature gauge on the refrigeration unit. Furthermore, the large metal pot with the remains of the sardine- mayonnaise salad had been kept in the kitchen unrefrigerated, where it was used to prepare additional plates; so at least a portion of the salad had gone unrefriger- ated until approximately 1:30 p.m., when the last trays were prepared and sent to the upstairs refrigerator on the serving line. The salad had been served from 12 noon until 2:00 p.m. on 5 May.

Table 1. Foods eaten at lunch and dinner on 5 May 1977 by ill and weIl students at the Trujillo University dining hall (Trujillo, Peru).

Food i tern

I11 (N = 79) Well (N = 27)

Total No. -Total No.

answering NO. % answering No. %

questions on eating eating questions on eating eating each item item i tern each item i tern item Lunch

Sardine- mayonnaise salad* soup Rice Vegetables Chicken Juice Dinner

soup Rice Yucca Meat Apples Tea

79 79 100 26 26 100

74 79 79 77 77 77 79 75 77 77 77 75 77

71 96* 26 13 50*

76 96 26 22 84

77 97 26 26 100

63 82 26 23 88

69 89 26 23 88

61 79 26 23 88

76 91: 26 23 88

45 60 23 13 58

71 92 23 23 100

59 77 21 16 76

67 87 23 20 87

25 33 23 17 74

64 83 23 22 95

*P < .OOOOOl by Fisher’s exac’t test; this was the only statistically significant association.

Table 2. Foods eaten at lunch on 5 May 1977 by kitchen employees at the Trujillo University dining hall (Truj;Uo, Peru).

Food item

Food handlers eating indicated item

Total NO. eating %

ill i tern ill

Food handlers not eating indicated item

Total No. eating %

ill item ill

Lunch 6 16 38 1 9 11

Sardine- mayonnaise

salad* 4 4 100* 3 12 25’

SOUP 6 12 50 1 4 25

Rice 7 16 44 0 0 0

Chicken 7 15 47 0 1 0

Juice 7 14 50 0 1 0

*P = .02 by Fisher’s exact test: this was the only statistically significant associa-

As previously noted,

Salmonella

Group Cl was isolated from all 40 stool specimens examined by the Microbiology Department of the Trujillo University Medical School. Approximately 30 unopened cans of sar- dines and some opened cans retrieved from the refuse bin were negative for Salmonella.One slightly swollen can from a lot approx- imately four years old yielded anaerobic growth, but it was found that the organism was not an enteric bacterium.

bacteria Reference Department in Lima. The U.S. Center for Disease Control con- firmed the identification of the

Salmonella

Group Cl isolates as S. thomfison but did not isolateSalmonella

from egg shells, en- vironmental surfaces, whole eggs, or the rectal swabs from the two food handlers.Discussion

A case-control analysis was performed in the course of this investigation to establish the epidemiologic association between ill- ness in students and ingestion of the sardine- mayonnaise salad. Food-specific attack rates are usually calculated in foodborne outbreaks if food ingestion histories can be obtained from most people involved or from a random sample of those people potentially exposed to the suspect food. In this investigation the large number of indi- viduals involved made it logistically impos- sible to obtain such histories (either from most ill persons or from a random sample of those persons), and this precluded a food-specific attack rate analysis. However, since over half of the kitchen employees were available for interviews, food-specific rates (see Table 2) were calculated for this group.

In the case-control study, patients from one hospital (cases) and well students (con- trols) who regularly ate at the dining hall provided two nonrandom “convenience” samples of students. There was no reason, however, to believe that either sample was biased with regard to possible exposure to risk factors (foods served) other than the causative risk factor (contaminated food). Statistical testing performed in this case- control analysis was based on that assump- tion.

The significant epidemiologic association between illness in students and employees and ingestion of sardine-mayonnaise salad implicated this food item as the vehicle of infection; however, the source of the

Sal-

monella

organisms that caused the outbreakis unknown.

Salmonellae

frequently con- taminate foods of animal origin -especially beef, poultry, and poultry products (1). Raw eggs used in the mayonnaise were the most likely source of Salmonella, even thoughSalmonella

was not isolated from the remaining eggs in the same shipment. One or several contaminated eggs could have heavily contaminated the entire salad mixture by mealtime, because this salad was virtually without refrigeration for a mini- mum of 1.5 to 3.5 hours.The time needed to produce a new gener- ation in the case of

Salmonella

can be as short as 30 minutes (2). In this regard, however, it is essential that the organisms have sufficient time to multiply at a suit- able temperature in order for an infective inoculum to be produced. Conversely, if a contaminated raw product (such as the egg or eggs probably responsible for this out- break) is properly refrigerated, it is unlike- ly to contain enough organisms to massive- ly contaminate the final food product and produce a high clinical rate of attack. In general, proper handling of eggs and other potentially contaminated products can pre- vent most foodborne outbreaks.Eggs can be contaminated by

Salmonella

present in the feces of egg-laying hens. The organisms can penetrate the intact shell, or else enter through cracks (checks) in the shell, and multiply within. Penetration and multiplication are affected by time, temperature, and humidity-being gener- ally favored by warmth and moisture (3, 4). Hens often become infected by eating contaminated feed and through contact with other infected hens in the crowded poultry farm environment. In contrast, commercially canned sardines are a very unlikely source of Salmonella.had any diarrhea1 illness in the week before the outbreak. Moreover, carriers without symptomatic diarrhea1 disease are generally much less effective disseminators of enteric organisms than carriers with diarrhea. Finally, even if a culture-positive food handler had been found, he could well have become infected by eating the food he was preparing.

The attack rate of 93% (with 91% of the patients being hospitalized) was unusually high, indicating that a large inoculum of

Salmonella

organisms was present in the sardine-mayonnaise salad. Experimental studies with volunteers have demonstrated that the symptom-producing mean infec- tive dose (IDso) of variousSalmonella

sero-types ranges from 106 to 108 organisms (5). Other possible explanations for the high clinical salmonellosis attack rate observed in this outbreak include (1) high infectivi- ty and virulence of the responsible

Salmo-

nella

strain, or (2) protection of the in- gested organisms from gastric acid by the ingested food.In conclusion, it should be noted that several food-handling problems-including lack of basic refrigeration and hand-wash- ing facilities-were observed at the kitchen- dining hall complex. Since such deficiencies increase the likelihood of future outbreaks, it is important to take account of their exis- tence and devote appropriate attention to their correction.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We wish to acknowledge the cooperation Hurtado (RN) of the Communicable Dis- and assistance provided by the medical and ease Eradication and Control Administra- university community in Trujillo, and by tion

(Direccih de Erradicacih

y Control

members of the Ministry of Health in Lima,de Enfermedades Transmisibles)

of the members of the Pan American Health Ministry of Health in Lima, who partici- Organization, and especially Dr. Victor pated in and aided the investigation.Manuel Noria Cabrera and Nurse Santos

SUMMARY

On 5 May 1977 an acute outbreak of gastro- enteritis occurred among university students at Trujillo, Peru. Prompt investigation pinpointed the responsible organism as

Salmonella

thomp- son that had contaminated a sardine-mayonnaise salad served at a university dining hall the day before. Though the source of the causative organism was not definitely determined, the Salmonella seems most likely to have come from one or more feces-soiled eggs purchased from a local farm on 4 May.Although this outbreak appears to have had no serious long-term effects, it hospitalized 545 students at the time and temporarily overloaded community medical services. The investigative methods applied in its wake provide a useful

REFERENCES

(I) Cohen, M., and P. A. Blake. Trends in tyfihimurium through the outer structures of foodborne salmonellosis outbreaks: 1963-1974. chicken eggs. Anian Dis 7:445-466, 1968. J Food Prot 40:798-800, 1977. (4) Adler, H. E. Salmonella in eggs: An

(2) Shands, J. W. Growth rate and toxicity of appraisal. Food Technol 19:191-192, 1965. Salmonella ty@himurizrm. J. Bacterial 89:799- (5) McCullough, N. B., and C. W. Eisele.

802, 1965. Experimental human salmonellosis. J Infect Dis

(3) Williams, S. E., L. H. Dillard, and G. 0. 88:278-289, 1951. Hall. The penetration patterns of Salmonella

MEETING ON INFANT AND YOUNG CHILD FEEDING