Sustained Competitive Advantage of Different Sized Multinational

Corporations in Rural Base of the Pyramid Markets:

An Exploration of Isolating Mechanisms from a Combined

Natural-Resource-Based View and Dynamic Capabilities Perspective

Maastricht University

School of Business and Economics Maastricht, 07.12.2015

Paul Geuting I6102371

i Acknowledgements

Herewith I would like to express my gratitude towards Dr. Marc van Wegberg who supervised and guided me throughout the whole thesis process. I very much appreciate his support and expertise regarding sustainability and scientific research.

ii Abstract

This thesis explores how multinational corporations of different sizes create barriers to imitation and therefore sustain competitive advantage in rural and informal Base of the Pyramid economies. These markets require close cooperation with local partners in a dynamic environment that lacks imposable property rights and follows a different rationale than developed markets. In order to explore how competitive advantage is sustained by different sized multinational corporations at the Base of the Pyramid, the natural-resource-based view and the dynamic capabilities perspective are integrated. Based on this integration the natural-resource-based view is extended by identifying critical dynamic capabilities that are assumed to be sources of competitive advantage at the Base of the Pyramid. Further, a contrasting case study explores how the identified dynamic capabilities are protected and their competitive advantage is sustained by isolating mechanisms that create barriers to imitation for a small to medium sized and a large multinational corporation. The case study results give grounds to assume that most resource-based isolating mechanisms create barriers to imitation that are fairly high for large and established multinational corporations that operate at the rural Base of the Pyramid and have a high product and business model complexity. On the contrary, barriers to imitation were found to be lower for young and small to medium sized multinational corporations with low product and business model complexity that according to some authors represent the majority of rural Base of the Pyramid companies. Particularly for small to medium sized multinational corporations the case study finds a relationship- and transaction-based unwillingness of local partners to act opportunistically rather than a resource-based inability to imitate. By offering an explanation of sustained competitive advantage for small to medium sized multinational corporations at the rural Base of the Pyramid this thesis closes an important research gap and recommends to include institutional and transaction-based research perspectives.

iii

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ... 1

2. Good Sustainability ... 3

3. Context –“Creating a fortune with the BoP”... 5

3.1 The BoP as Consumer ... 5

3.2 The BoP Market Environment ... 6

3.3 MNCs – Current Situation & Strategic Obstacles ... 7

4. Literature Review ... 9

4.1 Resource-Based View and Underlying Isolating Mechanisms ... 9

4.1.1 Isolating Mechanism: Unique Historical Conditions and Path Dependency ... 11

4.1.2 Isolating Mechanism: Social Complexity ... 11

4.1.3 Isolating Mechanism: Resource Interconnectedness ... 11

4.1.4 Isolating Mechanism: Causal Ambiguity (Tacitness, Complexity, Specificity) ... 12

4.2 Natural-Resource-Based View ... 12

4.3 Dynamic Capabilities Perspective ... 13

4.4 Integration of Natural-Resource-Based-View and Dynamic Capabilities Perspective ... 15

4.5 Extension of Integrated Theories and Definition of BoP Specific Dynamic Capabilities ... 16

4.5.1 Dynamic Capability: Bottom-up Business Model Innovation ... 16

4.5.2 Dynamic Capability: Partnering and Stakeholder Integration ... 17

4.5.3 Dynamic Capability: Regenerative Managerial Entrepreneurship ... 18

5. Research Gap and Model ... 19

6. Methodology ... 21

6.1 Case Study Approach ... 21

6.2. Sampling Strategy... 22

6.3. Data Collection Method... 23

6.4. Selected Cases ... 24

6.4.1 Case 1: Leef Blattwerk GmbH ... 24

6.4.2 Case 2: Millicom ... 25

6.4.3 Applied Selection Criteria ... 25

7. Data Analysis and Results ... 26

iv

7.2 Exploration of Dynamic Capabilities ... 27

7.2.1 Dynamic Capability: Bottom-up Business Model Innovation ... 27

7.2.2 Dynamic Capability: Partnering and Stakeholder Integration ... 28

7.2.3 Dynamic Capability: Regenerative Managerial Entrepreneurship ... 30

7.3 Exploration of Isolating Mechanisms ... 31

7.3.1 Isolating Mechanism: Unique Historical Conditions and Path Dependency ... 31

7.3.2 Isolating Mechanism: Social Complexity ... 31

7.3.3 Isolating Mechanism: Resource Interconnectedness ... 32

7.3.4 Isolating Mechanism: Causal Ambiguity (Tacitness, Complexity, Specificity) ... 33

7.4 Additional Findings ... 35

8. Discussion ... 35

8.1 Theory Development ... 35

8.1.1 Resource-Based Isolating Mechanisms at the BoP ... 35

8.1.2 Behavioral Isolating Mechanisms at the BoP – Handicap Signaling as a Relationship-Based Explanation of Inimitability ... 36

8.2 Limitations and Future Research ... 38

8.3 Practical Implications ... 39

9. Conclusion ... 40

Bibliography ... 42

Appendices ... 47

Appendix 1. Five-Step Research Approach ... 47

Appendix 2. Semi Structured Interview Guide ... 47

Appendix 3. Transcript Leef Blattwerk GmbH ... 51

v

List of Illustrations

Figure 1: The Sustainability Portfolio ... 4

Figure 2: Research Model ... 21

Figure 3: Research Model (Case Study Results) ... 38

1 1. Introduction

Nowadays, terrorism, civil wars and streams of refugees are ever-present and challenging phenomena with tremendous influence on the international political and social landscape. Many researchers argue that this is at least in part because those under a certain income threshold – commonly defined as Base of the Pyramid (BoP) – suffer from being excluded from the world’s

economic system, resulting in poverty and social inequality as important factors contributing to political and social turmoil (Burgoon, 2006; Moghaddam, 2005; Turk, 1982). At the same time

2

examined (Hart & Dowell, 2011; Hoskisson, Eden, Lau & Wright, 2000; Barney, Wright & Ketchen, 2001). In order to be successful at the BoP and create local growth, it is of utmost importance that MNCs are able to defend sources of competitive advantage from imitation by local alliance partners. Therefore, this thesis attempts to close this research gap by answering the following research question.

Research question: How do MNCs of different sizes sustain competitive advantage in rural and informal BoP economies?

The research question is answered along a five-step approach (see appendix 1). It starts with an introduction of the sustainability construct in chapter 2 and continues with a BoP context analysis

of benefits and obstacles that MNCs face when entering BoP markets in chapter 3. A thorough

literature review then introduces the resource-based view (RBV), the natural-resource-based view

(NRBV) and the dynamic capabilities perspective in chapter 4. In order to examine dynamic and

rural BoP markets, the NRBV, which focuses on external natural drivers of competitive advantage in stable market environments and the dynamic capabilities perspective that explains competitive advantage in dynamic markets, are combined (Hart, 1995; Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). After evaluating the NRBV and dynamic capabilities perspective as complementary, the NRBV is extended towards an explanation of competitive advantage at the BoP by categorizing three clusters of dynamic capabilities that are assumed to be critical success factors in informal and rural economies. After describing the research model and methods in chapter 5 and 6, a contrasting case study explores how barriers to imitation are raised by which isolating mechanisms in chapter 7. This analysis of how the identified dynamic BoP capabilities are protected as sources of sustained competitive advantage is conducted based on a large and a small to medium sized MNC. The contrasting case study does not intent to test the applicability of isolating mechanisms but develops theory based on an in-depth exploration of how barriers to imitation are created that takes into consideration various contextual factors.

Subquestion 1: How do MNCs of different sizes create barriers to imitation that successfully prevent the imitation of critical dynamic capabilities in rural and informal BoP economies?

Chapter 8 discusses the results of the case study, develops theory, outlines limitations as well as

3

evaluate the extent to which existing theories such as the NRBV are able to explain phenomena like sustained competitive advantage in emerging BoP markets (Aragón-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma & García-Morales, 2008; Hart & Dowell, 2011; Hoskisson, Eden, Lau & Wright, 2000). Hence, answering the second subquestion this thesis discusses whether an extended NRBV sufficiently explains inimitability and therefore sustainability of competitive advantage of large and small to medium sized MNCs in an informal and rural BoP environment or whether other research perspectives have to be integrated.

Subquestion 2: Does the extended NRBV sufficiently explain sustained competitive advantage in rural and informal BoP economies for MNCs of different sizes?

Finally, chapter 9 gives a summarizing conclusion and answers the above mentioned research and

subquestions.

2. Good Sustainability

In order to embed the thesis in a general scientific and practical context, the underlying concept of

sustainability is defined in this chapter. Further, an overview of sustainability strategies and an explanation of strategies that are currently applied by companies are given.

According to a report of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (Lebel & Kane, 1987), a generally accepted definition describes sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs” (p. 8). Important fields of action that have to be addressed in order to enable future generations to meet their needs are described by the triple bottom line and the environmental burden formula. According to the triple bottom line, the impact of sustainable activity may be measured in three terms: people, planet and profit (Elkington, 1998). While the people dimension aims at sustainable behavior towards all other human stakeholders that are linked to a company, the planet dimension is concerned with a fair treatment of the natural environment such as the reduction of the ecological footprint. Finally the concept of profit underlines the importance of financial autonomy as a basis for beneficial and long-term relationships that create mutual value (Elkington, 1998).

Another approach defines human impact on the environment based on the formula 𝐸𝐵 = 𝑃 ∗ 𝐴 ∗ 𝑇

(Ehrlich & Holdren, 1971). Having a closer look at this function consisting of population (P),

4 environmental burden (EB) can only be reduced by lowering one or more of those factors. A reduction of the population does not seem like an ethical target for planned intervention and decreasing affluence would most likely cause the population (P) to grow as there is a negative relationship between the degree of education that is linked to affluence and the number of born children (Basu, 2002; Hart, 1997). Therefore, only two options remain. While the innovation of technology (T) has the potential to reduce environmental burden, a stabilization of the world’s population can only be achieved if education and growth is brought to those living in poverty (Hart, 1997).

The way that companies deal with the above-mentioned fields of action developed evolutionarily. Today most companies have implemented incremental greening strategies that tackle environmental challenges of today such as pollution prevention and product stewardship strategies which focus on a more efficient use of existing technologies (Hart, 2005). The next step would be the implementation of disruptive beyond greening strategies such as clean technology and base of the pyramid that focus on the environmental challenges of the future by creating new sustainable solutions (Hart, 2005). Further, those strategies may be distinguished along their internal or external focus. While pollution prevention internally aims at avoiding waste before it is created, product stewardship goes beyond waste prevention and takes responsibility for the whole external product lifecycle. Clean technology strategies focus on the internal development of new innovations while BoP strategies require external business model adjustments to profitably address the needs of the poor (see figure 1).

Figure 1: The Sustainability Portfolio 1

1Adapted from “Beyond greening: strategies for a sustainable world” by S. Hart, 1997, Harvard Business Review,

5

Nowadays most companies incrementally focus on today’s challenges. However, it will be of crucial importance to disruptively address tomorrow’s challenges in the long run, taking into consideration the dimensions of the triple bottom line and the environmental burden formula.

3. Context –“Creating a fortune with the BoP”

Because the BoP was highlighted as a strategic and increasingly important field of sustainable action in the context of disruptive beyond greening strategies, the BoP as a target group as well as its market environment is defined in this chapter. Also an overview of potential strategic opportunities and threats that MNCs face when targeting BoP markets is provided.

3.1 The BoP as Consumer

There are several ways and attempts to define what is commonly understood as the BoP. A very comprehensive and comparable way of categorization is the definition of certain income thresholds. Prahalad and Hammond (2002) claim that 4 billion people (65% of the global population) earn less than $2,000 per year and therefore belong to the BoP.

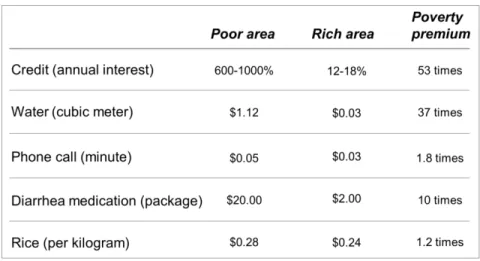

Another way of categorization would be purchasing power parity (PPP) as a ratio to identify BoP affiliation based on the relative price of a basket consisting of identical services and goods. Defined PPP values at the BoP differ from $1,500 to $3,000 annually and $1 to $4 per day (London & Hart, 2011). Some researchers define BoP affiliation more precisely with respect to the country, e.g. $3.35 (Brazil), $1.89 (Ghana), $2.11 (China) and $1.56 (India) a day (World Bank Group, 2007). Next to a relatively lower disposable income, Mendoza (2008) explored the poverty penalty concept and among other things finds that the target group at the BoP is penalized by higher prices or lower quality. Prahalad and Hammond (2002) also came to the conclusion that inhabitants of slums have to pay multiple times more for products and services such as drinking water and phone calls than first world consumers (see table 1).

6 Table 1: Examples Poverty Penalty Concept 2

Because a mere quantitative description of the target group is insufficiently preparing the following case analysis, it seems reasonable to additionally provide a detailed understanding of the BoP market that is based on a qualitative description of market characteristics and consumption behavior.

3.2 The BoP Market Environment

In general BoP markets are being characterized as dynamic, informal, heterogeneous and without functioning labor or product markets (London & Hart, 2011). While most BoP markets in Africa and Asia are characterized as community-based and rural, BoP markets in South America and Eastern Europe are mostly found in urban environments (World Bank Group, 2007).

London and Hart (2011) describe five key differences between doing business in BoP and Top of the Pyramid (ToP) markets. First of all, there are plenty of unaddressed basic needs at the BoP such as clean water supply, sanitation, healthcare and communications services. Second, poor infrastructure and undeveloped distribution channels make it difficult to scale businesses in a reliable way. Furthermore, people have restricted access to information, which increases communication problems from a marketing and sales perspective. Next, corruption is a severe problem in developing countries. As discussed before people in those low-income markets also have to pay relatively higher prices for basic products and services compared to those in the developed world.

2From “Serving the world´s poor, profitably” by C. Pralahad and A. Hammond, 2002, Harvard Business Review,

7

The fact that many poor people live in these relative high cost systems without the protection of laws, such as rent control or prevention of price gouging, is in part due to the existence of an

informal economy that follows different rules (Hart & London, 2005). Informal economies are much smaller in developed countries compared to developing countries. For example, the informal economy in Mexico is believed to make up for about 30% until 40% of the overall economy (De Soto, 2000). While business relationships in formal economies are mostly based on property rights

such as legal contracts and patents, the predominant regulators in informal economies are social ties and trust-based contracts (Hart & London, 2005; Munir, Gregg & Ansari, 2012; Reficco & Márquez, 2012). For instance, reliance on the community and social institutions to mediate between conflicting parties is high because many people do not own legal documents (London & Hart, 2005) such as contracts of land registration or formal leasing agreements. Further, Rufin and Rivera-Santos (2010) emphasize the importance of local social and business networks as a mechanism of institutionalizing and imposing agreements that are of a social rather than a legal nature.

3.3 MNCs – Current Situation & Strategic Obstacles

A MNC is defined as “a corporation that has its facilities and other assets in at least one country other than its home country. Such companies have offices and/or factories in different countries and usually have a centralized head office where they co-ordinate global management.” 3

Nowadays MNC are facing several challenges from different stakeholders. On one hand, internal stakeholders and shareholders expect MNCs to deliver high growth rates and profit margins in mainly saturated markets, where it becomes increasingly difficult to identify new products and growth opportunities (Hart & Christensen, 2002; Hart, 2005). On the other, MNCs have to meet social expectations articulated by governments and public society, represented by NGO´s and other interest groups that request a high degree of legitimacy and oppose unethical behavior such as pollution or third world exploitation (Werther & Chandler, 2005; Hart & Christensen, 2002). Currently the trend is shifting towards entering emerging markets such as Africa, Latin America, Eastern Europe and Asia that offer new growth opportunities (London & Hart, 2004; World Bank Group, 2007). Prahalad & Hammond (2002) name three opportunities that may solve the described challenges concerning growth and legitimacy as a result of targeting the BoP – top-line growth,

8

reduced costs and access to innovation. First, despite the fact that individual buying power is relatively low, the mere size of BoP markets results in top-line growth. Second, reduced costs might be achieved by operating in countries with lower labor and production expenses (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). Finally, using BoP markets as laboratories to disruptively innovate products and business models may result in a bottom-up transfer of knowledge from BoP to ToP markets (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002; Hart & Christensen, 2002).

Most companies that targeted BoP markets in the past focused on designing lower cost products that can be sold to the poor (Simanis & Hart, 2009). However, a new generation of BoP strategies has shown greater success with an incorporation of BoP perspectives and entrepreneurs in products and business models as consumers, producers and collaborators, meaning that those strategies do not aim at “creating a fortune at the base of the pyramid” but rather “creating a fortune with the base of the pyramid” based on cooperation and alliances (London & Hart, 2011, p. 1; Munir, Gregg & Ansari, 2012; Tashman & Marano, 2010).

9

and problems such as corruption and a lack of property rights constructs are assumed to be major obstacles that result in a lack of investment (Kistruck Sutter & Smith, 2013; Webb, Kistruck, Ireland & Ketchen, Jr., 2010). Because informal economies rely less on legal contracts and knowledge protection but more on social institutions, the monitoring of behavior and the avoidance of potential knowledge drain become increasingly difficult (Kistruck, Sutter & Smith, 2013). However, most strategies aggressively attempt to impose property rights instead of looking for different ways to protect resources (London & Hart, 2004).

So far, it has been examined that barriers to imitation from developed markets may insufficiently explain the protection of knowledge in informal BoP environments that appear to favor small to medium sized MNCs. In order to prepare an in-depth exploration of how barriers to imitation are created in dynamic and informal BoP economies, the next chapter introduces the central theories of this thesis.

4. Literature Review

In this chapter the interconnected underlying theories of this thesis, namely the RBV, the NRBV and the dynamic capabilities perspective, are introduced. Special emphasis is put on isolating mechanisms that raise barriers to imitation and therefore determine the sustainability of

competitive advantage. The NRBV and the dynamic capabilities theory were developed independently from each other and at different times. This thesis aims to integrate the two to apply them to dynamic BoP markets. Finally, after evaluating both theories as complementary the NRBV is extended towards an inclusion of external social drivers of competitive advantage by identifying central dynamic BoP capabilities that synchronize a company´s resource base with its socio-economic environment.

4.1 Resource-Based View and Underlying Isolating Mechanisms

10

advantage additionally requires the value of this strategy not to be replicated by the competition in the long run (Barney, 1991). According to Wernerfelt (1984) resources are defined as the tangible and intangible strengths and weaknesses such as brand, production facilities, workforce and information that are controlled by the firm. There are three categories of resources: physical resources such as facilities and machines; human resources like knowledge and social capital; and

organizational resources such as processes and decision making structures (Barney, 1991). Competences, that are also called organizational routines or processes, are organization wide enabling activities such as quality management or procurement (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997).

Core competences are defined as an organization’s essential and business driving competences

(Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997).

A basic assumption of the RBV is that resources and competences are distributed heterogeneously

11

those property-rights-based isolating mechanisms that legally prohibit imitation, competitive advantage may be rooted in resource characteristics themselves. According to Barney (1991) and Dierickx and Cool (1989) there are four central resource-based isolating mechanisms.

4.1.1 Isolating Mechanism: Unique Historical Conditions and Path Dependency

Unique historical conditions and path dependency are isolating mechanisms that create barriers to imitation because the resources a company possesses and the way it exploits them depend on its specific history and development (Barney, 1991). Due to the fact that resources and capabilities of a company follow a company-specific path and become co-specialized over time, they have to be developed internally as they cannot be acquired and exploited in a resource setting of another company (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Peteraf, 1993). For instance, imitating and exploiting the innovative culture of a company may be a challenge because it was influenced by the time it was founded and differentiated together with other resources and competences along its upcoming path.

4.1.2 Isolating Mechanism: Social Complexity

Another source of inimitability is social complexity, describing a company’s lack of understanding

concerning social events, situations or relationships such as managerial behavior or complex stakeholder relationships (Barney (1991). Because of their inherent social complexity these competences cannot be imitated even if competitors understand the causal relationship between resources and competitive advantages. For example imitating and exploiting complex factors such as leadership behavior is difficult as it is hardly possible to influence them in a systematic manner.

4.1.3 Isolating Mechanism: Resource Interconnectedness

12 4.1.4 Isolating Mechanism: Causal Ambiguity (Tacitness, Complexity, Specificity) Causal ambiguity describes the non-transparent connection between a company’s resources and its

competitive advantage (Barney (1991). Causal ambiguity requires both the company that owns the resources as well as the company that attempts to imitate them to lack the knowledge of which resources result in competitive advantage. This is because the knowledge about which resources have to be imitated could be obtained by hiring away key functions from the initial company by the competitor. Causal ambiguity can be based on: tacitness, complexity and specificity (Reed & De Fillippi, 1990).

Tacitness describes experience-based skills and behaviors that are not codified or written down and are a result of everyday repetition and learning-by-doing routines (Reed & De Fillippi, 1990; Tsang, 1998). Because of this high degree of informality, competitors are assumed to have difficulties to identify potential sources of competitive advantage.

Complexity contributes to inimitability due to complicated and inextricable norms such as behavioral patterns, technologies, skills and systems (Barney, 1991). Accordingly, the sources of competitive advantage are not transparent and may hardly be understood by individual employees (Reed & De Fillippi, 1990). Since a high concentration of knowledge makes a firm particularly vulnerable to competitors that may hire away knowledge-holding key individuals, complexity raises an important barrier to imitation that protects a company from undesired knowledge drain. Last but not least specificity describes ambiguity that is caused by a partner specific relationship that makes it difficult for competitors to understand the link between resources and competitive advantage by only examining the resources of the targeted firm without obtaining knowledge about the complementing resources of the partner as well (Dyer & Singh, 1998).

4.2 Natural-Resource-Based View

According to Branco and Rodrigues (2006) “one of the most important weaknesses of the RBV is related to the lack of understanding they provide on the influence that the relationships between a firm and its environment have on the firm’s success” (p. 118). In his pioneering paper A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm Hart (1995) also criticized that the RBV “systematically ignores

13

as global warming. Therefore, Hart (1995) included a natural perspective into resource-based and strategic management theory by promoting the already introduced three connected proactive environmental strategies (see figure 1) of pollution prevention (emission minimization), product stewardship (product life-cycle optimization) and sustainable development (reduction of negative environmental impact linked to a company´s growth ambitions, particularly in third world markets).

Applying the triple-bottom-line it can be seen that Hart (1995) approaches sustainability from a planet and profit rather than a people perspective. Although it cannot be denied that the environment has to be protected from unsustainable development in third world countries, Hart (1995) puts much less emphasis on socio-economic aspects concerning growth at the base of the pyramid than on pollution prevention and product stewardship strategies that target the natural environment. Hart recognized this himself and already in 1995 recommended further research on socio-economic BoP strategies based on case study approaches. Fifteen years after A Natural-Resource-Based View of the Firm was published in 1995, Hart and Dowell (2011) revisited and summarized the research efforts to develop a natural-resource-based view of the firm and conclude that most research still focuses on today´s internal pollution prevention rather than tomorrows external BoP strategies. Thus, Hart and Dowell (2011) point at a lack of research concerning the question of how MNCs may contribute to growth at the BoP and encourage to identify those dynamic capabilities that are necessary for MNCs to be successful in emerging markets. It is further claimed that so far the NRBV and the RBV have been mostly applied to explain sustained competitive advantage of large MNCs (Aragón-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma & García-Morales, 2008; Barney, Wright & Ketchen, 2001; Runyan, Huddleston & Swinney, 2007). Concerning the lack of BoP research in the context of the NRBV framework, this is of particular importance as BoP markets were identified to favor small to medium sized MNCs (Karnani, 2007; Karamchandani, Kubzansky & Frandano, 2009).

4.3 Dynamic Capabilities Perspective

14

and growth opportunities (Gupta, Smith & Shalley, 2006; Kogut & Zander, 1992; Wernerfelt, 1984). Therefore, a continuous adaption of resources as suggested by the RBV does not sufficiently explain the resource exploration activities that are necessary to respond to highly dynamic environments (Madhok, 1997; Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997). Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1997) extended the RBV towards an explanation of sustained competitive advantage in unstable and dynamic markets. Those high-velocity environments are being described as highly ambitious and determined by continuous industrial, socio-economic and regulatory changes (Barreto, 2010). Further, in those settings it is difficult to define market boundaries and successful best practice business models or companies (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000). Dynamic capabilities are defined as “the firm´s ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments” (Teece, Pisano & Shuen, 1997, p. 516) and consist of “specific strategic and organizational processes like product development, alliancing, and strategic decision making that create value for firms within dynamic markets by manipulating resources” (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000, p. 1106). In opposition to the continuous improvement routines in stable environments, as assumed by the RBV, different dynamic capabilities are required in high-velocity environments (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000).

15

sustainability depend on the already introduced VRIN characteristics (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Barney, Wright & Ketchen, 2001; Wang and Ahmed, 2007).

Summarizing, the RBV explains competitive advantage in a stable environment and was developed towards an inclusion of natural driving forces as determinants of competitive advantage by the NRBV. Little later the dynamic capabilities theory emerged, explaining competitive advantage in dynamic environments. While temporary competitive advantage in both dynamic and stable environments is rooted in resources and competences that are valuable and rare, sustained competitive advantage additionally requires them to be non-substitutable and inimitable.

4.4 Integration of Natural-Resource-Based-View and Dynamic Capabilities Perspective

The NRBV appears to be a suitable holistic framework to include the natural and socio economic environment into strategic management and a useful theory to explore the isolating mechanisms that create barriers to imitation in informal economies. However, as recommended by Hart and Dowell (2011) it has to be developed towards an explanation of competitive advantage at the BoP. At first sight applying the NRBV to highly dynamic BoP markets seems problematic as it is based on the RBV that explains competitive advantage in stable market environments. Integrating the NRBV and the dynamic capabilities theory may solve this problem. This is in line with Hart and Dowel (2011), who generally suggest that the NRBV and the dynamic capabilities perspective, which was introduced in the meanwhile as an extension of the RBV and describes competitive advantage in high-velocity markets, may mutually benefit from each other.

Although the NRBV (Hart, 1995) understands capabilities as bundled resources according to Barney´s (1991) definition, and not as the renewing dynamic capabilities described by Teece, Pisano and Shuen (1997), the dynamic capabilities theory is compatible with the NRBV for the following reasons.

16

Applying the hierarchical categorization of dynamic capabilities by Ambrosini, Bowman and Collier (2009) the NRBV´s greening strategies such as pollution prevention and product stewardship that deal with today’s internal and external challenges may further be understood as incremental dynamic capabilities (first level) that continuously improve a company´s resource base. Also the NRBV´s beyond greening strategies, such as clean technology and BoP that address tomorrow’s internal and external challenges, may be categorized as renewing dynamic capabilities (second level) that disruptively adapt a company´s resource platform to a dynamic and fast changing environment.

Summarizing, the basic constructs of the NRBV and dynamic capabilities perspective were identified as being compatible. Therefore, they appear to be suitable theories to examine isolating mechanisms that raise barriers to imitation in a dynamic, rural and informal BoP environment.

4.5 Extension of Integrated Theories and Definition of BoP Specific Dynamic Capabilities

Based on the integration of the NRBV and dynamic capabilities perspective, this chapter attempts to include the dynamic, external BoP environment into the NRBV by structuring BoP literature along different categories of relevant dynamic BoP capabilities. Those dynamic capabilities are assumed to be important success factors at the BoP because they adapt a company’s resource base to the requirements of its dynamic external environment.

4.5.1 Dynamic Capability: Bottom-up Business Model Innovation

17

disruptive innovations that may even result in a transfer to first world markets. It is further emphasized by Prahalad (2004) that a critical bottom-up questioning of existing solutions may contribute to a shift in the dominant and blinding logic of companies and industries. According to Ambrosini, Bowman and Collier (2009) this dynamic capability would be a renewing dynamic capability (second level), as offerings are created or changed bottom-up and the existing resource platform is modified in order to successfully respond to a dynamic market environment.

While a bottom-up innovation process might require disruptive elements in the first place, Sharma and Vredenburg (1998) introduce continuous innovation as a dynamic capability which adapts existing solutions to environmental changes. Continuous innovation may be considered to be an incremental dynamic capability (first level) that adapts existing products in order to gain temporary first mover advantages.

In summary, this category of dynamic capabilities aims at innovation at the BoP and consists of both incremental (first level) and disruptive (second level) innovation practices that include the community and the consumer as trusted partners.

4.5.2 Dynamic Capability: Partnering and Stakeholder Integration

As discussed in chapter 3, MNCs face the challenge of legitimate and ethical growth. In order to tackle this challenge, it is important to become indigenous instead of remaining alien (Hart, 2005). Although partnering and stakeholder integration has the potential to generate bottom-up innovation, this dynamic capability rather focuses on legitimacy and local trust building. The inclusion of fringe stakeholders and the development of solutions that preserve the culture of the community and protect its local nature is termed native capability by Hart and London (2005) and understands embeddedness as a source of legitimacy and competitive advantage. Hart and Sharma (2004) highlight that most managers only consider stakeholders that have a direct business impact and introduce the concept of radical transactiveness as a way “to systematically identify, explore,

18

Contradicting the dominant mind set of protecting company boundaries, the concept of building local capacity describes the integration of existing local structures into the business model (London & Hart, 2004). An example are localized production facilities and supply chains that allow the community to actively participate in the value creation process. The World Bank Group (2007) terms this approach localizing value creation and suggests to cooperate with the community as a customer and producer, for example by creating local ecosystems consisting of locally embedded agents. Also the construct of business model intimacy describes a situation of connected and shared identities that co-evolved between the company and the BoP community (Simanis & Hart, 2009). Understanding poverty not only in terms of income thresholds but the underdevelopment of capabilities, Munir, Gregg and Ansari (2012) consider it an obligation of MNCs to develop the capabilities of the local community in order to increase its autonomy for instance by establishing local training facilities for entrepreneurs. Because most MNCs rely on local labor markets, this is in line with Tashman and Marano (2010) who state that developing local capabilities improves the companies own resource base because of an increased business partner competence.

To summarize, this presumably second level dynamic capability emphasizes the ability to identify and deal with fringe stakeholders, to integrate the community into a localized business model and to develop its resources.

4.5.3 Dynamic Capability: Regenerative Managerial Entrepreneurship

19

understanding the complex and ambiguous business environment and to develop dynamic capabilities is a result of the management´s subjective interpretation. This is in line with Rosenbloom (2000) who states that it is a central leadership task and capability to break with old habits and to develop new approaches to old problems. Augier and Teece (2009) further develop this construct and emphasize that it is a management task to exploit short term opportunities as well as explore long term growth. This includes the analysis of the environment and the bundling of resources in a certain way by choosing strategies, distributing investments and designing routines. Consistent with this line of argumentation Aragón-Correa and Sharma (2003) claim that how management evaluates environmental uncertainty influences the way in which resources are exploited and dynamic capabilities are developed.

In summary, regenerative managerial entrepreneurship is a third level dynamic capability that directly influences all lower level dynamic capabilities and is rooted in a company´s management, supported by company culture and processes.

5. Research Gap and Model

20

regulators that are imposed by local networks (Hart & London, 2005; Munir, Gregg & Ansari, 2012; Reficco & Márquez, 2012).

Second, a lack of infrastructure and a high degree of geographical dispersion at the BoP appear to favor small to medium sized MNCs with a comparably simple product and business model (Karnani, 2007; Karamchandani, Kubzansky & Frandano, 2009). However, so far most scientific RBV and NRBV contributions have been focused on large MNCs and may therefore not be fully transferrable to small and medium sized MNCs in this specific BoP context (Aragón-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma & García-Morales, 2008; Barney, Wright & Ketchen, 2001; Runyan, Huddleston & Swinney, 2007). Aragón-Correa, Hurtado-Torres, Sharma and García-Morales (2008) state that the structural characteristics of small to medium sized MNCs differ from larger MNCs as they are less complex, have stronger personal ties and shorter communication paths. Therefore, it may be assumed that traditional isolating mechanisms, which apply to large MNCs in developed markets, are weaker or even not applicable at all to explain competitive advantage of small to medium sized MNCs in informal and rural BoP environments. For instance, there are grounds to assume that complexity and resource interconnectedness as traditional and resource-based isolating mechanisms may create lower barriers to imitation for small to medium sized than large MNCs due to smaller and less complex resource bases. This is an important research gap, as so far only little research has been conducted on small to medium sized MNCs in both RBV and NRBV literature and no one has yet specifically examined isolating mechanisms of small to medium sized MNCs in rural and community-driven BoP markets. Also practical relevance is high, because in an accelerating global environment, it is of utmost strategic importance for different sized MNCs to fully understand how dynamic capabilities can be protected from imitation based on existing or even new isolating mechanisms.

21 Figure 2: Research Model

The chosen inductive and explorative approach allows for an in-depth examination of underlying reasons and may contribute to an understanding of why certain known and mostly resource-based isolating mechanisms are more suitable than others in this specific context.

6. Methodology

In the following chapter the research design is introduced and the advantages and disadvantages of the chosen exploratory contrasting case study approach are discussed. Additionally, a detailed description of the sampling strategy and the method of data collection is given.

6.1 Case Study Approach

22

research requires theory development and the identification of underlying reasons before testing is possible. Following the definition of Yin (2013), a case study as “an empirical analytical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident” (p. 18) seems to be a suitable approach. A case study is a reasonable way to deal with a management dilemma and research question that is very broad and insufficiently studied because it takes into consideration the environment that the problem is embedded in from various perspectives and allows for the retrospective inclusion and adjustment of variables (Blumberg, Cooper, & Schindler, 2011). Following the recommendation of Hart (1995), a contrasting case study approach is chosen because studying the phenomenon in contrasting settings may allow to derive assumptions about other influential context variables (Blumberg, Cooper, & Schindler, 2011). Although the results of a case study are not generalizable, it is the objective of this thesis to inductively and qualitatively analyze data from various angles, build theory and derive propositions that are empirically testable by quantitative studies (Eisenhardt, 1989).

6.2. Sampling Strategy

Although most of the information is obtained by interviewing managers, the unit of analysis is MNCs operating at the rural BoP based on a socially embedded and mutually value creating business model. Because those BoP specific MNCs are rare and hard to find, this case applies a

23

In the context of the ongoing scientific discussions about the optimal size of MNCs operating at the rural BoP it seems further reasonable to compare the isolating mechanisms of a small and young with that of a large and established MNC.

6.3. Data Collection Method

Based on a classification of Blumberg, Cooper and Schindler (2011) this study may be categorized as a contrasting interrogation or communication case study because next to secondary data analysis, information is obtained from conversations and observations. The data collection process follows an explorative rationale and is based on a structured but cyclic, flexible and iterative approach. Therefore, it continuously narrows down the research problem, resulting in a continuous adaption of existing and the emergence of new questions due to an increasingly deeper understanding and novel practical implications (Tukey, 1980).

A thorough desk research of secondary data preceded the case selection and interview process in order to identify companies that may contribute to answering the research question according to the predefined factors of the judgment sampling strategy. After the selected cases were confirmed for investigation by the companies of interest, a more detailed screening of available documents was conducted on the internet and the companies were asked to provide internal documents about their history, business models, target groups etc.

24

After all, the data collection process is based on triangulation and information about the phenomenon of interest comes from different sources. For example, important information obtained from secondary data is again made a subject of discussion during the interviews to either confirm it or gain deeper insights. Additionally, observations of the company´s facilities and working conditions were included in the data analysis as field notes were taken throughout the entire duration of the interview and company visit.

6.4. Selected Cases

This chapter contains a description of the sampled companies. Further, it is argued why they are consistent with the sampling criteria described in the previous chapter.

6.4.1 Case 1: Leef Blattwerk GmbH

25 6.4.2 Case 2: Millicom

Millicom is a leading media and telecommunications company headquartered in Luxembourg with a focus on emerging African and Latin American high growth markets and has offices in Stockholm, London and Miami (Millicom.com, 2015). It was founded in 1990 when a Swedish investor and an American telecommunications company combined their mobile phone businesses and now offers a portfolio that consists of mobile, TV and broadband, online, e-commerce and mobile financial services (Millicom, 2014a). After difficult times in the early 2000s, Millicom recovered, changed its strategic focus and launched its brand Tigo in 2005 under which it now operates most of its services in developing countries (Josten, 2015). Today the company is world leader in mobile financial services and offers its digital portfolio to more than 56 million mobile customers in 40 markets with 23,297 employees generating revenues of $6.39 billion in 2014, mostly in the mobile segment (Millicom, 2014a). Millicom is a highly innovative corporation with the vision “to make affordable, useful and fun services available to everybody“, and although its prevalent motive is profit orientation, the company is “proud to be a responsible corporate citizen […] who contributes to the country’s economic growth” (Millicom, 2014b). Moreover, Millicom articulated a detailed corporate social responsibility agenda and cooperates with several NGO´s to contribute to the socio-economic development of the countries it operates in via various social projects (Millicom, 2014b).

6.4.3 Applied Selection Criteria

26

selected to represent larger MNCs that are the most important drivers of growth according to Hart (2005) and Prahalad and Hammond (2002). Thus, a contrasting comparison may result in interesting insights about differences in how barriers to imitation are raised by isolating mechanisms in rural BoP environments that are related to age size, product and business model complexity.

7. Data Analysis and Results

This chapter assesses the suitability of the sampled companies in terms of their business models, the market environments they operate in, the necessity to open up their resource bases and the extent to which they can rely on property-rights-based constructs. Moreover, the way each company implemented the three identified dynamic capabilities is described. In a next step it is explored how those dynamic capabilities are defended by isolating mechanisms that raise barriers to imitation.

7.1 Assessment of Companies and Market Environment

27

market and to be ahead of the competition that attempts to copy. Josten (2015) also underlines that competitive advantage at the BoP is mostly temporary and that it is therefore important to always adapt and keep moving. Joint Ventures are an important way of cooperation for Millicom because they help to integrate market specific knowledge of local partners and minimize the risks of entering new markets (Josten, 2015). Leef also relies on cooperation with its producers and suppliers that are characterized as intimate and close (Vietta, 2015). In both cases formal property rights constructs are applied but evaluated as less effective than in first world markets for two reasons. First, governmental institutions such as ministries and courts of justice are described as much less reliable and more corrupt, increasing the difficulty to impose the validity of contracts or patents (Vietta, 2015). Second, contractors and even consumers may feel less obliged to obey formalized laws, resulting in product piracy (Millicom, 2014a) or the proactive disregard of contractual agreements, for instance concerning the prevention of child labor in the supply chains of local partners (Vietta, 2015).

7.2 Exploration of Dynamic Capabilities

The theoretically anticipated dynamic capabilities that are assumed to be important factors of success were found in both companies but were implemented differently.

7.2.1 Dynamic Capability: Bottom-up Business Model Innovation

The dynamic innovation capability of Leef may be characterized as rather unorganized and incremental (Vietta, 2015). Although the CEO is in charge of final decisions, frequent round-table discussions are held with producers, local consumers and employees to openly discuss product adaptions (Vietta, 201 5). Next to this rather continuous innovation approach, Leef further uses a not-for-profit business unit that targets music festival business customers as a laboratory to disruptively innovate and test new products and ideas (Vietta, 2015).

28

2014a; Think.rw, 2015). Moreover, the Digital Changemaker Award Program is a project that rewards novel ideas and aims at identifying disruptive innovations (Millicom, 2014a; Tigo.co.rw, 2015).

Summarizing, Leef applies top-down and bottom-up innovation routines that are hands on, situation-based, unorganized and mostly driven by its founder. While the product is continuously adapted based on the feedback of consumers, producers and employees, Leef uses its not-for-profit unit as a laboratory to disruptively innovate and test new ideas. Millicom does not have a central innovation policy or process and the country units are responsible to synchronize their offerings with the dynamic market demands. Those decentral innovation processes are very developed and consist of top-down and bottom-up channels such as incubators and competitions to disruptively generate ideas.

7.2.2 Dynamic Capability: Partnering and Stakeholder Integration

Leef attempts to identify and protect fringe stakeholders such as nature or the native populations of the communities it operates in (Vietta, 2015). However, this happens in an unstructured way. Leef uses its in-house NGO Leef Love to cooperate with non-traditional partners (Leef.is, 2015). Further, Leef is socially embedded and has a good reputation in the community in which it maintains two local partnerships and is being perceived as a fair employer that provides safe working conditions and pays wages that are above market average (Vietta, 2015). According to Vietta (2015) this local embeddedness is much more sustainable than contract-based relationships. Further it is assumed that the very close and trust-based cooperation with the local suppliers and the commitment of the employees that result in mutual support is mainly due to the fact that the community and the employees believe in the sustainable motive and benevolence of the company (Vietta, 2015). This high degree of trust already resulted in the rejection of more profitable opportunities that were offered to the local BoP partner (Vietta, 2015). Finally, Leef actively develops the capabilities of its local partners in terms of working safety, quality standards and the protection of nature (Vietta, 2015).

29

company also maintains partnerships with non-traditional partners such as UNICEF, IWF, INHOPE and Interpol in an attempt to integrate fringe perspectives and to fight phenomena such as child abuse and labor (Millicom, 2014b). The company has a sustainable supply chain, values social embeddedness and always had a solid presence in and very intimate relationships with the local community (Josten, 2015). The fact that 99% of the employees belong to the local population and that the workforce consists of more than 56 nationalities underline its local embeddedness (Millicom, 2014a). According to Josten (2015) Millicom is convinced that its engagement as a corporate citizen strengthens the local brand and contributes to the stability of the socio-economic landscape the company operates in. In order to preserve these relationships, suppliers and customers are visited on a regular basis (Millicom, 2014b). However, it is admitted that high staff turnover rates may result in a comparably low degree of personalization of relationships towards local partners (Josten, 2015). Millicom also invests in community skill development and training facilities such as EduMe, a vocational academy that transfers important business skills to local entrepreneurs (Edume.com, 2015; Millicom, 2014a). Another example is the Tigo Sales School, an eight week skill development program that is based on interactive mobile learning tools and class lectures that address internal sales staff as well as external freelancers and indirect employees (Josten, 2015; Millicom, 2014b).

30 7.2.3 Dynamic Capability: Regenerative Managerial Entrepreneurship

Leef is a young, dynamic and fast-growing start-up company with flat hierarchies, a flexible and open-minded working environment and a low degree of process institutionalization (observation, September 18, 2015; Vietta, 2015). This unconventional working environment and the low institutionalization of routines enable the management team and the employees to freely interpret the company´s environment and adapt structures and routines in a creative and flexible manner (Vietta, 2015). Next to a flexible adaption of dynamic capabilities, the start-up culture and low degree of formalization further result in high degrees of self-responsibility, commitment and intrinsic motivation of employees and partners (observation, September 18, 2015; Vietta, 2015). According to Vietta (2015) this entrepreneurial spirit helps the company to flexibly adapt to its dynamic market environment and to maintain the reputation of a socially embedded and sustainable organization that is perceived as more trust-worthy than large MNCs that run the risk of being perceived as anonymous, process dominated and shareholder value oriented.

Because of its size-related more bureaucratic and complex structures and decision making processes, the top management of Millicom defined structures that incentivize a managerial entrepreneurship culture and foster a creative and open-minded interpretation of the dynamic company environment and an efficient adaption of internal structures and resources (Josten, 2015). Therefore, Millicom actively attempts to reduce structural complexity and to develop entrepreneurial leadership capabilities based on trainings and development programs such as the

31 7.3 Exploration of Isolating Mechanisms

It is the aim of the following analysis to explore how and which isolating mechanisms create barriers to imitation to protect the identified dynamic capabilities of each company. Thus, it does not intend to evaluate the dynamic capabilities’ effectiveness or their outcomes.

7.3.1 Isolating Mechanism: Unique Historical Conditionsand Path Dependency

Based on the conducted analysis, age appears to influence this isolating mechanism as older companies with a more specific and path dependent development may possess dynamic capabilities that are rather unique and more embedded in a differentiated resource base. For instance Millicom has complex processes that uniquely developed and co-specialized over time with the company´s remaining resources and processes. An example of a historical event that contributed to the uniqueness of a dynamic capability is its strategic shift away from saturated markets towards developing countries that was due to a barely avoided bankruptcy in the early 2000s (Millicom, 2014a). According to Josten (2015) this experience of failure influenced the development of today’s more experimental and open minded approach towards innovation. Also Millicom´s partnering and stakeholder integration routines developed over a long time and became increasingly embedded and unique. Examples of its differentiated stakeholder routines are its

corporate responsibility committee that translates stakeholder interests into activities and its unique reputation among NGO´s and governmental institutions (Josten, 2015). Further, Millicom´s entrepreneurial management routines are difficult to imitate as they are influenced by complex organizational management processes, many levels of hierarchy and reporting structures that developed and grew path dependently (Josten, 2015). Leef on the contrary has a relatively short history resulting in processes that are mostly simple and neither institutionalized nor unique (observation, September 18, 2015; Vietta, 2015). Further, most routines are not very co-specialized and integrated in its remaining resource base (Vietta, 2015).

Proposition 1: Unique historical conditions and path dependency may raise a higher barrier to imitation for older and larger MNCs operating at the rural BoP due to dynamic capabilities that

are more unique and embedded in the remaining resource base

7.3.2 Isolating Mechanism: Social Complexity

32

towards stakeholders and partners. For instance Leef only needs a relatively small number of individuals to innovate a fairly simple product but the degree of social complexity inherent in its bottom-up innovation activities with partners and stakeholders is considered to be high (Vietta, 2015). This is because Leef is socially embedded in the community, has an excellent reputation among stakeholders and maintains relationships with its partners and stakeholders that are described as intimate and based on trust and interpersonal empathy (Vietta, 2015). Finally, Leef´s regenerative managerial entrepreneurship capability which is influenced by its young and dynamic entrepreneurial culture, flexible decision making structures and the commitment of its employees is a highly relationship-based and socially complex phenomenon (observation, September 18, 2015; Vietta, 2015). Millicom on the contrary has higher fluctuation rates that result in a lower duration, consistency and social complexity of interpersonal relationships that are characterized as more transactional than relationship-based (Josten, 2015). Also the size-related extent to which the company is perceived as shareholder driven, which is perceived as intimidating by some local partners, influences the degree of trust and intimacy as determinants of social complexity (Josten, 2015). Moreover, it is assumed that Millicom´s approach to entrepreneurship is of reduced social complexity because it is highly institutionalized and based on the regulation of behavior via structures, rules and policies (Josten, 2015).

Proposition 2: Social complexity may raise a higher barrier to imitation for younger and smaller MNCs operating at the rural BoP due to higher consistency of interpersonal relationships and

higher perceived trustworthiness

7.3.3 Isolating Mechanism: Resource Interconnectedness

33

on cross-divisional reporting and management systems that require a high degree of resource interconnectedness (Josten, 2015). While Millicom has many partners on a global scale, a large production and sales volume as well as complex and interconnected IT and resource planning systems, resource interconnectedness is low for Leef because of its small size and because it only has two local partners (Josten, 2015; Vietta, 2015). Leef´s pragmatic approach to leadership and its comparably small size also reduce the necessity to apply interconnected regenerative managerial entrepreneurship routines and reporting structures (Vietta, 2015).

Proposition 3: Resource interconnectedness may raise a higher barrier to imitation for older and larger MNCs operating at the rural BoP that offer a complex product due to a higher number of

internal and external intersection points

7.3.4 Isolating Mechanism: Causal Ambiguity (Tacitness, Complexity, Specificity)

Comparing the results of the case analysis, tacitness may be relatively high within small and young companies that sell a simple product because size, age, product and business model complexity appear to result in an increased necessity to plan and codify processes and routines. Leef for instance does not yet codify, map or design processes and the way the company practices innovation changes on a daily basis (Vietta, 2015). Further, it maintains personal relationships with its stakeholders that are not based on a defined process and its approach to managerial entrepreneurship is hands-on, experience-based and pragmatic (Vietta, 2015). On the contrary, Millicom has advanced process management capabilities that it applies to systematically design and improve most company activities and although being decentral, Millicom´s innovation processes are clearly defined and codified (Josten, 2015). Millicom´s central corporate responsibility committee that deals with stakeholder management from a headquarters perspective is a good example of the systematic way in which stakeholder management routines are described (Josten, 2015). Finally, Millicom codifies entrepreneurship via guiding leadership principles, decision processes and management tools that describe and influence entrepreneurship practices (Josten, 2015).

34

At this point it is important to underline that complexity as a source of causal ambiguity may be of an organizational nature and should not be confused with social complexity as the already introduced isolating mechanism that is fully relationship-based. In direct comparison, the results of the interviews imply that older and larger companies selling high technology products seem to have an advantage as the degree of complexity is increased by all those factors. For instance, Millicom has an extensive enterprise resource planning and several IT systems involved in its innovation process (Josten, 2015). Also partnering and stakeholder integration routines are very complex as they involve several parties and interfaces that have to be operationalized and require points of intersection between external partners and internal corporate functions (Josten, 2015). Moreover, complexity is an important isolating mechanism for Millicom’s managerial entrepreneurship routines due to its diverse reporting systems and decision making structures (Josten, 2015). Complexity as a source of causal ambiguity appears to be less important for Leef because its innovation process solely relies on the CEO as the only central coordinating function, who is also the only interface towards its few external partners (Vietta, 2015). Due to its size Leef´s managerial entrepreneurship capability is assumed to be of comparably low complexity (Vietta, 2015).

Proposition 5: Complexity may raise a higher barrier to imitation for older and larger MNCs operating at the rural BoP that offer a complex product due to lower resource transparency

The results of the case study imply that age and size as possible proxies for the duration and number of partner relationships may further influence the specificity of dynamic capabilities and the mutual development of resources and routines. Millicom for instance integrates the perspectives and opinions of several target groups and stakeholders, resulting in a high number of advanced, long-lasting and partner specific innovation and stakeholder processes (Josten, 2015). Millicom´s long lasting stakeholder relationships also co-developed and resulted in a high degree of specificity on an entrepreneurship and reporting level (Josten, 2015). On the contrary, specificity is assumed to be rather low ifor Leef, because it just started to infrequently and informally integrate partners in its innovation and stakeholder routines (Vietta, 2015).

Proposition 6: Specificity may raise a higher barrier to imitation for older and larger MNCs operating at the rural BoP due to more and longer partner-relationships as well as a higher

35 7.4 Additional Findings

It is an unexpected finding of the case analysis that the BoP partners of the explored companies did not act as opportunistic as expected (Josten, 2015; Vietta, 2015). Especially in the case of Leef Vietta (2015) admits that not much stands in the way of copying its relatively simple business model and dynamic capabilities. Vietta (2015) even states that most of the time openness and cooperation were rewarded with respect and assumes that this unwillingness to defect is due to relationship-based control mechanisms and an effective alignment of interests (Vietta, 2015). As an example he mentions that investing in relationships and being part of local networks enable a company to punish opportunistic behavior by damaging the reputation of the defecting partner (Vietta, 2015). If the company is socially embedded and its interests are aligned with that of its partners and the community, the punishment of the defecting partner might even be carried out by third parties that benefit from the MNCs presence (Vietta, 2015). Compared to the other isolating mechanisms, this barrier to imitation is of a behavioral nature and based on a lack of willingness rather than a resource-based lack of opportunity because BoP partners have specific subjective reasons not to act opportunistically.

Proposition 7: The behavior of BoP partners may be based on an unwillingness rather than a resource-based inability to act opportunistically due to informal social control mechanisms such

as reputation

8. Discussion

This chapter develops theory based on the case study findings and comments on its theoretical and practical implications. Further, limitations and future research opportunities are discussed.

8.1 Theory Development

This thesis attempts to develop theory towards an explanation of an observed real-world phenomenon – the inimitability of dynamic capabilities in an environment that follows different rules than developed markets – that is insufficiently covered by existing theory.

8.1.1 Resource-Based Isolating Mechanisms at the BoP