w w w . r b o . o r g . b r

Original

Article

Prevalence

of

nonspecific

lumbar

pain

and

associated

factors

among

adolescents

in

Uruguaiana,

state

of

Rio

Grande

do

Sul

夽

,

夽夽

Susane

Graup

∗,

Mauren

Lúcia

de

Araújo

Bergmann,

Gabriel

Gustavo

Bergmann

FederalUniversityofthePampa(Unipampa),Uruguaiana,RS,Brazil

a

r

t

i

c

l

e

i

n

f

o

Articlehistory:

Received15August2013 Accepted5September2013 Availableonline16October2014

Keywords: Lumbarpain Adolescent Sex

Bodymassindex

a

b

s

t

r

a

c

t

Objective:To identifythe prevalenceofnonspecific lumbarpain and associatedfactors amongadolescentsinUruguaiana,stateofRioGrandedoSul.

Methods:Thiswasacross-sectionalschool-basedstudyconductedamongadolescentsaged 10–17yearswhowereenrolledinthedayshiftofthemunicipalandstateeducational sys-temsofUruguaiana.Thisstudyevaluated1455adolescents.Thedata-gatheringprocedures involvedtwostages.Firstly,aquestionnaireonsociodemographicindicators,behavioral patternsandhabitsofthedailyroutineandhistoryofnonspecificlumbarpainwasapplied. Subsequently,height,bodymass,flexibilityandabdominalstrength/resistance measure-mentswereevaluated.Toanalyzethedata,univariate,bivariateandmultivariablemethods wereusedandthesignificancelevelwastakentobe5%forallthetests.

Results:The prevalence of lumbar pain among the adolescents evaluated was 16.1%. Groupedaccordingtosex,theprevalenceamongmaleswas10.5%andamongfemales, 21.6%.Thevariablesofsex,bodymassindex,abdominalstrength/resistanceandphysical activitylevelpresentedstatisticallysignificantassociationswithnonspecificlumbarpain. Intheadjustedanalysis,sex(OR=2.36;p<0.001),age(OR=1.14;p<0.001)andbodymass index(OR=1.44;p=0.029)maintainedsignificanceinthefinalmodel.

Conclusions: Femaleadolescentsofolderageandwhopresentedoverweightorobesityhad higherchancesofdevelopingnonspecificlumbarpain.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublishedbyElsevierEditora Ltda.Allrightsreserved.

Prevalência

de

dor

lombar

inespecífica

e

fatores

associados

em

adolescentes

de

Uruguaiana/RS

Palavras-chave: Dorlombar

r

e

s

u

m

o

Objetivo:Identificaraprevalência dedorlombarinespecíficaeosfatoresassociadosem adolescentesdeUruguaiana/RS.

夽

Pleasecitethisarticleas:GraupS,deAraújoBergmannML,BergmannGG.Prevalênciadedorlombarinespecíficaefatoresassociados emadolescentesdeUruguaiana/RS.RevBrasOrtop.2014;49:661–667.

夽夽WorkdevelopedwithintheChairofPhysicalEducation,FederalUniversityofthePampa(Unipampa),Uruguaiana,RS,Brazil.

∗

Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:susanegraup@unipampa.edu.br,susigraup@gmail.com(S.Graup). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rboe.2014.10.003

Adolescente Sexo

Índicedemassacorporal

Métodos: Estudotransversaldebaseescolar,feitocomadolescentesde10a17anos matri-culadosnoturnodiurnodasredesmunicipaleestadualdeensinodeUruguaiana/RS.Foram avaliados1.455adolescentes.Oprocedimentodecoletadosdadosocorreuemduasetapas. Inicialmentefoiaplicadoumquestionáriosobreindicadoressociodemográficos, compor-tamentosehábitosdarotinadiáriaehistóricodedorlombarinespecífica.Posteriormente foramavaliadasasmedidasdeestatura,massacorporal,flexibilidadeeforc¸a/resistência abdominal.Paraa análisedos dadosforamusadososmétodosunivariado,bivariado e multivariávelefoiconsideradoníveldesignificânciade5%paratodosostestes.

Resultados: Aprevalênciadedorlombarnosadolescentesavaliadosfoide16,1%.Porsexo,o masculinoapresentouumaprevalênciade10,5%eofeminino,de21,6%.Asvariáveissexo, índicedemassacorporal,forc¸a/resistênciaabdominaleníveldeatividadefísica apresen-taramassociac¸ãoestatisticamentesignificativacomadorlombarinespecífica.Naanálise ajustadaosexo(OR=2,36;p<0,001),aidade(OR=1,14;p<0,001)eoíndicedemassacorporal (OR=1,44;p=0,029)mantiveramsignificâncianomodelofinal.

Conclusões: Adolescentes dosexo feminino queapresentaramidades mais elevadas e estavam com sobrepeso ou obesidade têm mais chances de desenvolver dor lombar inespecífica.

©2014SociedadeBrasileiradeOrtopediaeTraumatologia.PublicadoporElsevier EditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Nonspecific lumbar pain is considered to be one of the main health problems in industrialized countries1 and it has increased considerably over recent decades among adolescents.2 Theearliestcasesofnonspecificlumbarpain occurinthe agegroupfrom 11to12 years,withagradual increaseofapproximately10%peryear,untilreachingaround 50%ofadolescents attheageof18years.3Thisproblemis evenmoresignificantwhenitisperpetuatedintoadulthood.4 Itisdifficulttoidentifytheetiologyoflumbarpainbecause it is manifested under various conditions5 and is often of multifactorial nature.6 Among other causes, lumbar pain presentsanassociationwithindividuals’lifestyles,suchthat overweight,7–9sedentarism8,9 andremainingincertain posi-tionsforlongperiodsoftime7,10aretriggeringfactorsforthis problem.

Inthiscontext,astudyconductedamongschoolchildrenin Florianópolis,stateofSantaCatarina,showedthat25.5%ofthe individualswhofeellumbarpainindicatethatthetriggering factorfortheirpainfulstateconsistsofsituationsinwhich theyremaininaseatedpositionforlongperiods.10Inaddition, adolescentswhooccupytheirtimedoingactivitiesthatallow diversityofposturepresent achanceofdevelopinglumbar painthatis2.3timeslowerthantheratepresentedbytheir sedentarypeers.11

On the other hand, high levels of physical activity are positivelyassociatedwiththeappearanceofnonspecific lum-barpain.3,4,7However,thisassociationneedstobeanalyzed cautiously, since continuous well-guided physical activity practices contribute toward better posture and lower inci-denceoflumbarpain.

Itisimportanttoemphasizethatlumbarpainisnota spe-cificpathologicalconditionbut,rather,asymptomthatmay berelatedtoadisease12andwhich,withthepassageoftime, mayresultinadegenerativemusculoskeletaldisorder2,7with thecapacitytoreducetheindividual’sfitnessforwork.13Thus,

knowledgeoftheetiologyoflumbarpainandtheassociated factors inadolescentsmay helptopreventandunderstand theprobleminadults.14

Thepresentstudyhadtheobjectiveofanalyzingthe preva-lenceofnonspecificlumbarpainandtheassociatedfactors amongadolescentsinUruguaiana,stateofRioGrandedoSul (RS).

Method

This was a school-based cross-sectional study conducted amongadolescents aged10–17years who were enrolledin thedaytimeshiftofthemunicipalandstateschoolnetwork ofUruguaiana,RS.Thisstudyformedpartofalargerproject developedin2011,underthetitle“Habitualphysicalactivity andassociatedfactorsamongschoolchildreninUruguaiana, RS”,whichwasapprovedbyourinstitution’sresearchethics committee(protocol042/2010)andfollowedtheguidanceof Resolution196/96oftheNationalHealthCouncil.

and17yearsatthe10schoolsthatweredrawnwereinvitedto participate.Onlystudentswhopresentedafreeandinformed consentstatementsignedbyanadultresponsible forthem andwhoexpressedwillingnesstoparticipatewereincluded inthesamplecomposition.

The data-gathering procedure comprised two stages. Firstly,aquestionnairestructuredintosectionswasapplied toalltheindividualswhomadeupthesample.The question-nairecontainedquestionsrelating to:(a)sociodemographic indicators;(b)behaviorandhabitsofthedailyroutine (includ-ingphysicalactivity);and (c)history ofnonspecificlumbar pain.In thesecond stage,anthropometricand motor mea-surementsweremade. Thedatawere gatheredbyagroup oftrainedevaluators(teachersandstudents/bursary-holders attheinstitutionwherethestudywasconducted).The data-gatheringperiodwasfromMaytoNovember2011.

Nonspecific lumbar pain (dependent variable) was esti-matedusing anadaptation ofthe instrument proposed by Sjoileetal.16 Theadolescentsgaveresponsestothe follow-ingquestion:“Haveyoueverhadpainordiscomfortinyour back,inthelumbarregion?”Therewasadrawingbesidethe question that indicated the location ofthe lumbarregion. Theresponsespossiblewere:never;onlyafewtimes;often; andallthetime.Fortheanalyses,thecategoriesof“never” and“onlyafewtimes”were groupedandconsidered tobe “withoutlumbarpain”andthecategoriesof“often”and“all thetime”weregroupedand consideredtobe“withlumbar pain”.

Thevariables that formedthesociodemographic indica-tors were: (a) sociodemographic level (in conformity with theBrazilianeconomicclassificationcriteriadividedintofive levelsfromAtoE)17;(b)sex(maleorfemale);and(c)age (com-pletedyears).

Theindicatorsofbehavioranddailyroutinehabitswere: (a)timespentdoingsedentaryactivities,involvinguseof tele-visions,electronicgamesandcomputers(≤3hor>3h);and (b)habitualphysicalactivitylevel,usingaquestionnairefor physicalactivitiesamongchildrenandadolescents:Physical ActivityQuestionnaireforOlderChildren(PAQ-C)18and Ado-lescents(PAQ-A).19ThePAQ-C/PAQ-Acontainsninequestions withfivepossibleresponses.Eachresponseisscoredfrom1to 5,thusproducingthefinalscoreforeachquestionnaire.The individualswere classifiedinto tercileswithregardtotheir physicalactivitylevels:“leastactive”(tercile1),“intermediate” (tercile2)and“mostactive”(tercile3).

The anthropometric and motor activities evaluated were: height, body mass, flexibility and abdominal strength/resistance. Body mass measurements were made withtheaidofaPlenna®digitalbalance(Plenna,SãoPaulo, Brazil)withacapacityof150kgandprecisionof100g.Height wasmeasuredincentimeters,withonedecimalplace,with theaidofameasuringstickfixedtothewall.Theindividuals were positioned in accordance with the Frankfurt plane, usingasetsquareonthehead.Bothoftheseanthropometric measurements were made in accordance with standard procedures.20 Thebody mass index (BMI)was obtained by dividingthebodymassinkilogramsbytheheightinmeters squared and was categorized as“normal weight” or “over-weight”(theoverweightandobesecategoriesweregrouped), inconformitywiththeproposalofColeetal.21

Flexibilityand abdominalstrength/resistancewere mea-sured using the sit-and-reach test and according to the number of sit-ups that could be done in one minute, respectively. Themeasurementprocedure followedthe rec-ommendations of the Brazilian sports project (Proesp).22 Throughusingspecificcutoffpointsaccordingtosexandage, flexibilityandabdominalstrength/resistancewereclassified as“lessthanrecommended”or“recommended”.

Toanalyzethedata,univariate,bivariateandmultivariable methods were used. In the univariate analysis, the abso-luteandrelativefrequencies(proportions)wereusedforeach ofthevariables studied,followedbycalculationofthe 95% confidenceinterval(95%CI).Forthebivariateanalysis,the chi-squaredtestforheterogeneityandchi-squaretestforlinear trend were used. In this analysis, each independent vari-ablewascorrelatedwiththedichotomizeddependentvariable (“withoutlumbarpain”or“withlumbarpain”).Alsoforthe bivariate analysis,Student’st-testforindependentsamples wasusedtotestthedifferencebetweenthemeanagesofthe groupswithandwithoutlumbarpain.

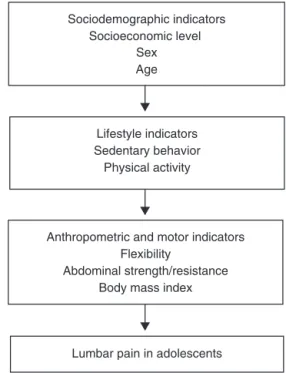

In the multivariable analysis, binary logistic regression wasused.Nonspecificlumbarpainwasdichotomizedasan outcome.Eachoftheindependentvariablesinthisanalysis wasenteredinconformitywiththehierarchicaltheoretical model thatwas constructed(Fig. 1). Thetheoretical model usedthreecausaldeterminationlevels(proximal, intermedi-ateanddistal).Thefirstlevel(sociodemographicindicators) includedthesocioeconomiclevel,ageandsex.The interme-diate level(lifestyleindicators)includedsedentarybehavior andphysicalactivity.Thelastlevel(anthropometricandmotor indicators)includedthebodymassindex,flexibilityand mus-clestrength/resistance.Thefinalmultivariablemodeltookthe independentvariablesthatpresentedp-values<0.05into con-siderationasfactorsassociatedwithnonspecificlumbarpain.

Lifestyle indicators Sedentary behavior

Physical activity Sociodemographic indicators

Socioeconomic level Sex Age

Anthropometric and motor indicators Flexibility

Abdominal strength/resistance Body mass index

Lumbar pain in adolescents

Results

Fortheanalyses,dataon1455adolescentsweregathered.To calculatetheprevalencesoflumbarpain,1377individualswho filledoutalltheinformationneededweretakeninto consid-eration.

Theprevalenceoflumbarpainamongtheadolescents eval-uatedwas 16.1%.Dividedaccording tosex,themalegroup presentedprevalenceof10.5%(n=71)andthefemalegroup, 21.6%(n=151).

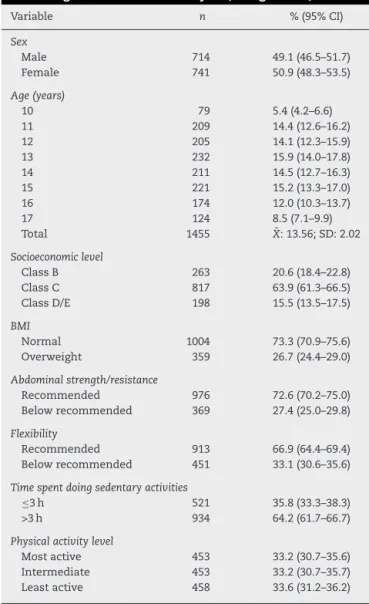

Thefrequencydistributionofthevariablesanalyzedis pre-sentedinTable1.Fromthis,itcanbeseenthat26.7%ofthe individualsevaluatedwereoverweight andthat64.2%were spendingmorethanthreehoursadaydoingsedentary activ-ities.

Theresultsfromthe chi-squaretestindicated thatonly thevariablesofsex,BMI,abdominalstrength/resistanceand physicalactivitylevelpresentedstatisticallysignificant asso-ciationswithnonspecificlumbarpain(p<0.05),asshownin

Table1–Frequencydistributionamongtheadolescents accordingtothevariablesanalyzed,Uruguaiana,2012.

Variable n %(95%CI)

Sex

Male 714 49.1(46.5–51.7)

Female 741 50.9(48.3–53.5)

Age(years)

10 79 5.4(4.2–6.6)

11 209 14.4(12.6–16.2)

12 205 14.1(12.3–15.9)

13 232 15.9(14.0–17.8)

14 211 14.5(12.7–16.3)

15 221 15.2(13.3–17.0)

16 174 12.0(10.3–13.7)

17 124 8.5(7.1–9.9)

Total 1455 X¯:13.56;SD:2.02

Socioeconomiclevel

ClassB 263 20.6(18.4–22.8) ClassC 817 63.9(61.3–66.5) ClassD/E 198 15.5(13.5–17.5)

BMI

Normal 1004 73.3(70.9–75.6) Overweight 359 26.7(24.4–29.0)

Abdominalstrength/resistance

Recommended 976 72.6(70.2–75.0) Belowrecommended 369 27.4(25.0–29.8)

Flexibility

Recommended 913 66.9(64.4–69.4) Belowrecommended 451 33.1(30.6–35.6)

Timespentdoingsedentaryactivities

≤3h 521 35.8(33.3–38.3)

>3h 934 64.2(61.7–66.7)

Physicalactivitylevel

Mostactive 453 33.2(30.7–35.6) Intermediate 453 33.2(30.7–35.7) Leastactive 458 33.6(31.2–36.2)

n,samplenumber;%,proportionofsample;95%CI,95%confidence interval; ¯Xmean;SD,standarddeviation.

Table 2. Inrelationtoage, thet-testindicatedthat adoles-cents whoreportedhavinglumbarpainhadahighermean agethanthosewhoreportedthattheydidnotfeelanylumbar pain(t=−3.61;p<0.05).

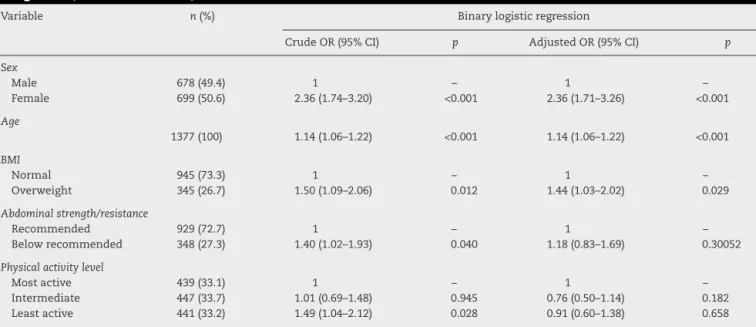

Thecrudeoddsratio(OR)valuesfromthebinarylogistic regressionanalysesconfirmedtheresultsfromtheanalyses onthechi-squaretest.Fromcombinedanalysis(adjustedOR), sex,ageandBMImaintainedtheirsignificanceinthemodel.It isworthemphasizingthattheresultsfromtheadjustedbinary logisticregressionanalysisindicatedthatfemaleadolescents presentedapproximatelya2.3-foldgreaterchanceofhaving lumbarpainthan theirpeers.Inrelationtoage,itcouldbe seenthatwitheachyearthatpassed,thechanceoflumbar painincreasedby14%(Table3).

Discussion

Nonspecific lumbarpain inadolescents hasbeenthe focus ofseveralstudiesbecauseofthehighprevalencesfoundin theliteratureandbecauseofthemultifactorialnatureofits etiology.4,6,7,11,23–29

In this context, the results showed that the preva-lence of nonspecific lumbar pain among the adolescents in Uruguaiana (16.1%)was lower than the rates presented in the literature, which have ranged from 20% to 60%, approximately.4,7,10,28,29

However, this result needs to be analyzed attentively, because sociocultural, environmental and genetic aspects ofthe reality analyzedshould betakeninto consideration, which adds difficulty toextrapolating the results to differ-ent contexts.30 Moreover, Masiero et al.25 commented that thedifferentconclusionsregardingtheprevalenceoflumbar pain may berelatedtothe study design,sampleselection, instrumentusedformeasurementsandthegeographicalarea, amongotherfactors.

Sexhas beenindicated asoneofthe factorsassociated withnonspecificlumbarpain,25,28,29,31,32whichisinlinewith the findings from the present study, which showed that females were moreaffected bypainfulconditionsand pre-sentedarounda2.4-foldgreaterchancesofpresentinglumbar painthanshownbymales.

Thefactthatfemalespresentedgreaterprevalenceofpain can be explained by cultural issues, in that women may demonstrate their feelingmore,28 along withtheir specific anatomofunctionalcharacteristics,suchaslessadaptationto sustained physicaleffort andjoints thataremorefragile.33 Itneedstobeemphasizedthatthedifferencesbetweenthe sexes may be linked to endogenous pain modulation sys-temsthatcontributetowardgreatersensitivitytoandgreater prevalenceofavarietyofpainfulconditionsamongwomen.34 Moreover,perceptionsofpainmaybeaffectedbyhormonal alterationsinducedbypuberty.7

The association between age and lumbar pain has been shown to be positive, with increasing prevalence as age increases. This makes it possible to speculate that lumbarpainduringchildhoodispredictiveoflumbarpainin adulthood.27,31

Table2–Resultsfromchi-squareanalysisbetweenlumbarpainoccurrences(yes/no)andthecategoricalvariables studiedamongadolescentsinUruguaiana,RioGrandedoSul,2011.

Variable Lumbarpain p

Yes%(95%CI) No%(95%CI)

Sex <0.001

Male 10.5(8.2–12.7) 89.5(87.2–91.7)

Female 21.6(18.6–24.6) 78.4(75.4–81.4)

Socioeconomiclevel 0.292

ClassB 19.7(14.9–24.5) 80.3(75.4–85.1)

ClassC 15.2(12.7–17.7) 84.8(82.3–87.7)

ClassD/E 16.7(11.5–21.9) 83.3(78.1–88.5)

BMI 0.009

Normal 14.5(12.3–16.7) 85.5(83.3–87.7)

Overweight 20.3(16.1–24.5) 79.7(75.5–83.9)

Abdominalstrength/resistance 0.026

Recommended 14.5(12.3–16.7) 85.5(83.3–87.7)

Belowrecommended 19.3(15.3–23.3) 80.7(76.7–84.7)

Flexibility 0.473

Recommended 15.8(13.4–18.2) 84.2(81.8–86.6)

Belowrecommended 16.2(12.8–19.6) 83.2(79.7–86.7)

Timespentdoingsedentaryactivities 0.168

≤3h 14.7(11.6–17.7) 85.3(82.2–88.3)

>3h 16.9(14.5–19.3) 83.1(80.7–85.5)

Physicalactivitylevel 0.024

Mostactive 14.1(10.9–17.3) 85.9(82.7–89.1)

Intermediate 14.3(11.0–17.6) 85.7(82.4–90.0)

Leastactive 19.7(16–23.4) 80.3(76.4–84.0)

%,proportionofsample;95%CI,95%confidenceinterval;p,significancelevel.

lumbarpain and age,28 thereby strengthening the findings from the present study, in which a significant increase in prevalencerelatingtoadvancingagewashighlighted.

Theincrease inprevalenceaccording to age may result from accumulated overload on the spine caused, among

other factors, by carrying backpacks and other heavy objects and by remaining in a seated position for long periods.31

The variable of socioeconomic level was not found to presentanyassociationwithlumbarpain.Thisvariableneeds

Table3–Crudeandadjustedoddsratiosforlumbarpain(yes/no)andfactorsassociatedwithpainamongadolescentsin Uruguaiana,RioGrandedoSul,2011.

Variable n(%) Binarylogisticregression

CrudeOR(95%CI) p AdjustedOR(95%CI) p

Sex

Male 678(49.4) 1 – 1 –

Female 699(50.6) 2.36(1.74–3.20) <0.001 2.36(1.71–3.26) <0.001

Age

1377(100) 1.14(1.06–1.22) <0.001 1.14(1.06–1.22) <0.001

BMI

Normal 945(73.3) 1 – 1 –

Overweight 345(26.7) 1.50(1.09–2.06) 0.012 1.44(1.03–2.02) 0.029

Abdominalstrength/resistance

Recommended 929(72.7) 1 – 1 –

Belowrecommended 348(27.3) 1.40(1.02–1.93) 0.040 1.18(0.83–1.69) 0.30052

Physicalactivitylevel

Mostactive 439(33.1) 1 – 1 –

Intermediate 447(33.7) 1.01(0.69–1.48) 0.945 0.76(0.50–1.14) 0.182 Leastactive 441(33.2) 1.49(1.04–2.12) 0.028 0.91(0.60–1.38) 0.658

tobeanalyzedcautiouslyinthisregard,giventhat socioe-conomic level is related to several other factors and may serveasaconfoundingvariableincasesofsignificant asso-ciationswithlumbarpain.35Nonetheless,astudyconducted amongthe populationof Salvador,stateofBahia, also did not find any significant association between lumbar pain and socioeconomic level among the subjects evaluated.36 Likewise,among students inLondrina, state ofParaná, no associationwasfoundbetweenbackpainandsocioeconomic class.37

BMIalsopresentedasignificantassociation with condi-tionsoflumbarpainamongtheadolescentsevaluatedhere and corroborated the results from the meta-analysis pre-sented by Shiri et al.38 regarding the association between lumbarpainandobesity.Theyconcludedthatbothoverweight andobesityincreasedtheriskoflumbarpainandalso sug-gestedthattheassociationbetweenoverweightorobesityand theprevalenceoflumbarpainwasstrongeramongwomen thanamongmen.

Inthiscontext,obesityhasanegativeimpactonchildren’s osteoarticular health, because it promotes biomechanical alterations in the lumbar spine and triggers significantly greaterfrequencyoflumbarpainamongobeseindividuals.39

However, in an analysis by Jannini et al.32 on muscu-loskeletalpainamongadolescents,theprevalenceoflumbar painwas notfoundtobegreater amongobese individuals thanamongnormal-weightindividuals.Evenso,backpainis themostfrequentpainfulmanifestationamongobese chil-drenandadolescentsandaffectsapproximately39%ofthese individuals.40

Reviewstudieshaveindicatedthatbackpaininchildren andadolescentsmaybeassociatedwithseatedpositions, pos-turaldeviationsandalsoweaknessoftheabdominalmuscles, amongotherfactors.7,41Inthepresentstudy,lumbarpainwas correlatedwithabdominalstrength/resistance,which corrob-oratesthisinformation.

Jonesetal.6alsofoundsignificantdifferencesinabdominal resistance among adolescents with lumbar pain, in com-parison with adolescents without pain. However, Balagué, TroussierandSalminen7showedthatlumbarpainatschool agecannotsimplybeattributedtomuscleweakness.Thisis becausethereseemstobeacorrelationbetweenshortening oftheposteriormusclesofthethighandlumbarpain.This informationisreinforcedbythestudybyFeldmanetal.,35who assessedadolescentsandfoundanassociationbetween lum-barpainandshorteninginthehamstringmusclesandinthe femoralquadriceps.

Inthepresentstudy,noassociationwasidentifiedbetween lumbarflexibilityandoccurrencesoflumbarpain.Thisresult maybeassociatedwiththefactthatthereisnoconsensus regardingwhattheappropriatevaluesforprotectionagainst casesoflumbarpainwouldbe.7,41 Inthisregard,onestudy foundthatonlyintermediatetrunkflexibilityvaluesprovided protectionagainsttheappearanceoflumbarpain,sincevalues indicatinghypomobilityandhypermobilitywerepredictiveof theappearanceoftheproblem.5

However, this lack of consonance in the informa-tion may be related to the group studied, since the morphological differences between the sexes may affect the results. Thus, the fact that women present greater

flexibility and lower abdominal resistance values may give rise to higher prevalence of lumbar pain among women.6

Thetimespentdoingsedentaryactivitiesdidnotpresent anyrelationshipwiththestatesoflumbarpainpresentedby theindividualsevaluated.Thisresultdifferedfromwhatwas found inastudy amongschool childreninBauru, stateof SãoPaulo,inwhichitwasshownthatindividualswhospent morethantwohourswatchingtelevisionpresentedan86% greaterchanceofhavinglumbarpain.28However,ithastobe borneinmindthattheassociationbetweenthetimespent doingsedentary activitiesandthepresenceoflumbarpain isnotwelldefinedamongstudents,whichshowsthelackof studies.41

A study conducted in Italy by Masiero et al.25 among adolescentsaged13–15yearsfoundanassociationbetween nonspecificlumbarpainandfemalesex,familyhistoryand sedentarism. Asimilarresultwas foundbyNoll etal.,29 in analyzing factorsassociatedwithbackpain among adoles-cents.

Regarding the association between the physical activity levelandlumbarpain,thecrudeanalysisshowedthat adoles-centswhowerelessactivehadhigherchancesofpresenting lumbarpain.However,whentheanalysiswasadjustedforthe sociodemographicvariables,theassociationceasedtopresent statisticalsignificance.

These results are in line with information available in the literature that indicates that there is no consistency in the results regarding the association between physical activity and lumbar pain. Results stating that lower lev-els of physicalactivity are associated withlumbarpain in adolescents11,24andthatvigorousphysicalactivitypractices alsomayincreasethechanceoflumbarpaininadolescents31 areavailableintheliteratureandindicatethatfurtherstudies ontheassociationbetweenthesevariablesneedtobe con-ducted.

Theresultsfromthepresentstudyprovideevidencethat contributes toward better comprehension of lumbar pain amongadolescents.However,certainlimitationsneedtobe takenintoconsideration.Sincethiswasaschool-basedstudy, theresultscannotbegeneralizedtoalloftheadolescentsin thecity.Althoughsignificantassociationswerefoundbetween lumbar pain and some independent variables, it was not possibletoestablishthecausalitybecausethiswasa cross-sectionalstudy.

Conclusions

In relation to the factors associated with lumbar pain, the adjusted model indicated that sex, age and BMI were the factors that predicted cases of lumbar pain. Female sex, greater age and overweight or obesity increased the chance of presenting nonspecific lumbar pain among the adolescents in Uruguaiana, state of Rio Grande do Sul.

Conflicts

of

interest

r

e

f

e

r

e

n

c

e

s

1. MacielSC,JenningsF,JonesA,NatourJ.Thedevelopmentand validationofalowbackpainknowledgequestionnaire–LKQ. Clinics.2009;64(12):1167–75.

2. HakalaP,RimpeläA,SalminenJJ,VirtanenSM,RimpeläM. Back,neck,andshoulderpaininFinnishadolescents: nationalcrosssectionalsurveys.BMJ.2002;325(7367):743. 3. PhélipX.Whythebackofthechild?EurSpineJ.

1999;8(6):426–8.

4. HarrebyM,NygaardB,JessenT,LarsenE,Storr-PaulsenA, LindahlA,etal.Riskfactorsforlowbackpaininacohortof 1389Danishschoolchildren:anepidemiologicstudy.Eur SpineJ.1999;8(6):444–50.

5. PolitoMD,MaranhãoNetoGA,LiraVA.Componentesda aptidãofísicaesuainfluênciasobreaprevalênciade lombalgia.RevBrasCiêncMov.2003;11(2):35–40.

6. JonesMA,StrattonG,ReillyT,UnnithanVB.Biologicalrisk indicatorsforrecurrentnon-specificlowbackpainin adolescents.BrJSportsMed.2007;39(3):137–40.

7. BalaguéF,TroussierB,SalminenJJ.Non-specificlowbackpain inchildrenandadolescents:riskfactors.EurSpineJ.

1999;8(6):429–38.

8. HestbaekL,KorsholmL,Leboeuf-YdeC,KyvikKO.Does socioeconomicstatusinadolescencepredictlowbackpainin adulthood?Arepeatedcross-sectionalstudyof4771Danish adolescents.EurSpineJ.2008;17(12):1727–34.

9. SatoT,HiranoT,MoritaO,KikuchiR,EndoN,TanabeN.Low backpaininchildhoodandadolescence:across-sectional studyinNiigataCity.EurSpineJ.2008;17(11):1441–7. 10.GraupS,SantosSG,MoroAR.Estudodescritivodealterac¸ões

posturaissagitaisdacolunalombaremescolaresdarede federaldeensinodeFlorianópolis.RevBrasOrtop. 2010;45(5):453–9.

11.AlpalhãoV,RobaloL.Algiasvertebraisnosadolescentes: associac¸ãocomasatividadesdetemposlivres

autorreportadas.Essfisionline.2005;2(1):3–15. 12.EhrlichGE.Lowbackpain.BullWorldHealthOrgan.

2003;81(3):671–6.

13.SalminenJJ,ErkintaloMO,PenttiJ,OksanenA,KormanoMJ. Recurrentlowbackpainandearlydiscdegenerationinthe young.Spine(PhilaPA1976).1999;24(13):1316–21.

14.MerlijnVP,HunfeldJA,VanDerWoudenJC, Hazebroek-KampschreurAA,KoesBW,PasschierJ. Psychosocialfactorsassociatedwithchronicpainin adolescents.Pain.2003;101(1):33–43.

15.Inep.InstitutoNacionaldeEstudosePesquisasEducacionais AnísioTeixeira.CensoEscolardaEducac¸ãoBásica.Available from:http://portal.inep.gov.br/basica-censo[accessedon 10.10.10].

16.SjölieAN.Low-backpaininadolescentsisassociatedwith poorhipmobilityandhighbodymassindex.ScandJMedSci Sports.2004;14(3):168–75.

17.Anep.Associac¸ãoNacionaldeEmpresasdePesquisa.Critério declassificac¸ãoeconômicaBrasil.SãoPaulo:Associac¸ão NacionaldeEmpresasdePesquisa(dadoscombaseno levantamentosocioeconômico2009);2011.

18.CrockerPR,BaileyDA,FaulknerRA,KowalskiKC,McgrathR. Measuringgenerallevelsofphysicalactivity:preliminary evidenceforthePhysicalActivityQuestionnaireforOlder Children.MedSciSportsExer.1997;29(10):1344–9.

19.KowalskiK,CrockerP,FaulknerR.Validationofthephysical activityquestionnaireforolderchildren.PediatrExercSci. 1997;9(2):174–86.

20.LohmanTG.Applicabilityofbodycompositiontechniques andconstantsforchildrenandyouths.ExercSportSciRev. 1986;14:325–57.

21.ColeTJ,BellizziMC,FlegalKM,DietzWH.Establishinga standarddefinitionofchildoverweightandobesity worldwide:internationalsurvey.BMJ.2000;320(7244):1240–3. 22.Proesp.ProjetoEsporteBrasil.Availablefrom:

www.proesp.ufrgs.br/proesp/[accessedon15.03.11]. 23.Cardoso-MonterrubioA,Balmaceda-CalderónC.Lumbalgia

enni ˜nosyadolescentes.Revisiónetiológica.RevMexOrtop Traum.2000;14(5):402–7.

24.CoelhoL,AlmeidaV,OliveiraR.Lombalgianosadolescentes: identificac¸ãodefatoresderiscopsicossociais.Estudo epidemiológiconaRegiãodaGrandeLisboa.RevPortSaúde Pública.2005;2(1):81–90.

25.MasieroS,CarraroE,CeliaA,SartoD,ErmaniS.Prevalenceof nonspecificlowbackpaininschoolchildrenagedbetween13 and15years.ActaPædiatr.2008;97(2):212–6.

26.PelisseF,BalaguéF,RajmilL,CedraschiC,AguirreM, FontechaCG,etal.Prevalenceoflowbackpainanditseffect onhealth-relatedqualityoflifeinadolescents.ArchPediatr AdolescMed.2009;163(1):65–71.

27.AyanniyiO,MbadaCE,MuolokwuCA.Prevalenceandprofile ofbackpainnigerianadolescents.MedPrincPract.

2011;20(4):368–73.

28.DeVittaAL,MartinezMG,PizaNT,SimeãoSF,FerreiraNP. Prevalênciaefatoresassociadosàdorlombaremescolares. CadSaúdePública.2011;27(8):1520–8.

29.NollM,CandottiCT,TiggemannCL,SchoenellMCW,VieiraA. Prevalênciadedornascostasefatoresassociadosem escolaresdoensinofundamentaldomunicípiodeTeutônia. RioGrandedoSul.RevBrasSaúdeMaternInfant.

2012;12(4):395–402.

30.PaananenMV,TaimelaSP,AuvinenJP,TammelinTH,

KantomaaMT,EbelingHE,etal.Riskfactorsforpersistenceof multiplemusculoskeletalpainsinadolescence:a2-year follow-upstudy.EurJPain.2010;14(10):1026–32.

31.ShehabDK,JarallahKF.Nonspecificlow-backpaininKuwaiti childrenandadolescents:associatedfactors.JAdolesHealth. 2005;36(1):32–5.

32.JanniniSN,Dória-FilhoU,DamianisD,SilvaCA.

Musculoskeletalpaininobeseadolescents.JPediatr(RioJ). 2011;87(4):329–35.

33.SilvaMC,FassaAG,ValleNC.Dorlombarcrônicaemuma populac¸ãoadultadoSuldoBrasil:prevalênciaefatores associados.CadSaúdePública.2004;20(2):377–85.

34.QuitonRL,GreenspanJD.Sexdifferencesinendogenouspain modulationbydistractingandpainfulconditioning

stimulation.Pain.2007;132Suppl.1:S134–49.

35.FeldmanDE,ShrierI,RossignolM,AbenhaimL.Riskfactors forthedevelopmentoflowbackpaininadolescence.AmJ Epidemiol.2001;154(1):30–6.

36.AlmeidaIC,SáKN,SilvaM,BaptistaA,MatosMA,LessaI. Prevalênciadedorlombarcrônicanapopulac¸ãodacidadede Salvador.RevBrasOrtop.2008;43(3):96–102.

37.RossetoEG,PimentaCA.Prevalênciaecaracterizac¸ãodador recorrenteemescolaresnacidadedelondrina.CiêncCuid Saúde.2012;11Suppl.:211–9.

38.ShiriR,KarppinenJ,Leino-ArjasP,SolovievaS,Viikari-Juntura E.Theassociationbetweenobesityandlowbackpain:a meta-analysis.AmJEpidemiol.2010;171(2):

135–54.

39.DeSáPintoAL,deBarrosHolandaPM,RaduAS,VillaresSM, LimaFR.Musculoskeletalfindingsinobesechildren.J PaediatrChildHealth.2006;42(6):341–4.

40.StovitzSD,PardeePE,VazquezG,DuvalS,SchwimmerJB. Musculoskeletalpaininobesechildrenandadolescents.Acta Paediatr.2008;97(4):489–93.