Publications

from the Caribbean in the

Health Sciences1

GEORGE ALLEYNE,~ GABRIELA FORT,~

MERCEDES VARGAS,~ & MAGDA ZIVER~

444

The invesfigation reported here examined scientific publications from Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago over the period 1976-1990. Its purpose was fo provide new information about Caribbean research in the health field through assessment of published works. To this end a broad array of journal subject categories was examined using SCISEARCH, an in- ternational index of medical and scientific literature. In all, 1 712 titles (articles, editorials, reviews, letters, meeting abstracts, and notes) were selected for analysis.

This analysis indicated that Jamaica accounted for abouf three-quarters of fhe titles and fhaf there had been a steady increase in the number of titles published over the study period thaf was most marked in Barbados. Most of the principal authors were affiliated wifh the University of the West Indies, and nearly one-third of the titles were published in the West Indian Medical Journal, the sole publication from the three study countries that SCI- SEARCH lisfed.

Most of the subjects covered fell wifhin the area of ‘general medicine” rather than ex- perimental medicine or public health. However, of the 383 titles dealing with experimental medicine, nearly all (331) originated in Jamaica. In codrast, less than half of the 262 titles in the public health field came from Jamaica, a relatively large number (106) originating in Trinidad and Tobago. Most of the 1 712 fitles (63.8%) dealt with topics oufside the priority areas identified by the Caribbean Ministers of Health as part of the Caribbean Cooperation in Health (CCH) Inifiafive.

T

here is growing acceptance of the view that much of the discussion on what constitutes development has been too narrow. The United Nations Devel- opment Program’s (UNDP) Human De- velopment Report of 1990 was perhaps a watershed here, in that it clearly set out a more acceptable approach to human development-defined as a “process of enlarging people’s choices”-and de- scribed the components of that devel- opment. Health figures prominently in this document as both an essential in- gredient and powerful instrument of hu- man development (2).It is also accepted that research must be an integral part of all efforts to im- prove health, and that attention to health research is not the exclusive province of the developed countries. It is true that as health concerns become ever more uni- versal in nature, the research carried out in various parts of the world may also have an increasingly global reach and sig- nificance. Nevertheless, the Commission on Health Research for Development? has argued that research is particularly im- portant in developing countries, noting that it serves the following four main purposes: (1) to identify and set priorities

‘This article will also be published in Spanish in the Boletin de la Oficina Sanitaria Panamericana, Vol. 119, 1995.

2Pan American Health Organization.

3The Commission on Health Research for Devel- opment, an independent international initiative, was formed in late 1987 with the aim of improving the health of people in developing countries.

among health problems; (2) to guide and accelerate application of knowledge to solving health problems; (3) to develop new tools and fresh strategies; and (4) to advance basic understanding and the frontiers of knowledge (2). This view that local research is important for solution of local problems and for training has been argued very strongly with reference to the Caribbean, many examples being provided to substantiate the claim (3).

In consonance with the Commission’s views and with concern for health re- search in Latin America and the Carib- bean, for 37 years the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) has main- tained an active program of research pro- motion, stimulating development of re- search policies (4) and supporting research in critical areas. It has also examined re- search outputs in specific countries from time to time (5), the most recent study of this nature reviewing research in five countries of the Americas with special attention to the influence of the economic crisis on scientific production (6).

One of the more extensive studies on scientific production in Latin America and the Caribbean was carried out toward the end of the 1980s by the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) (7). Data from this study on the Bank’s member coun- tries (including Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago) showed that be- tween 1973 and 1984 Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Venezuela generated 89% of the region’s scientific output, and that the percentage of scientific publica- tions devoted to the health sciences fell steadily in this period. The study also reported that while this region had about 8% of the world’s population in 1985 and generated 6% of its GDP, it accounted for only 1.4% of the world’s scientific pub- lications. Within this context, the study found that the three English-speaking Caribbean countries studied here ac- counted for approximately 3% of the re-

gion’s scientific publications between 1973 and 1984.

Despite the relatively limited size of this latter contribution, the English- speaking Caribbean has a long tradition of health research and development. This has been described (8) as having two main phases. First there was an age when en- terprising individuals performed re- search dedicated mainly to describing in- teresting local medical phenomena. This was followed by a second phase that saw a growing influence of institutions such as the University of the West Indies and the Commonwealth Caribbean Medical Research Council-the latter being the main agent responsible for articulating policy and attempting to steer research into priority areas defined by the Carib- bean Ministers of Health. The most re- cent definition of these priority areas was made in connection with the Caribbean Cooperation in Health (CCH) Initiative. The CCH, launched by the Caribbean Ministries of Health in 1986 with the sup- port of PAHO and the Caribbean Com- munity (CARICOM) Secretariat, seeks to mobilize a wide range of resources to fo- cus on specific priority areas and to stim- ulate technical cooperation among the Caribbean countries themselves (9).

Regarding other research-related insti- tutions, since its inception in 1948 the University of the West Indies has estab- lished a tradition of research into the main problems of the Caribbean. Within this context, the permanence of the univer- sity’s staff has permitted chosen lines of inquiry to be followed. In addition, the Medical Research Council of Great Brit- ain established two research units in the university, creating a core of people ded- icated exclusively to research in this field and providing significant training of Caribbean nationals in research.

Although not primarily a research in- stitution, PAHO has two centers in the Caribbean, the Caribbean Epidemiology

Center and the Caribbean Food and Nu- trition Institute. Through these centers it has provided an opportunity for several of its staff members to make significant contributions to research in the health sciences.

There have been very few attempts to analyze this Caribbean research, even to the extent of examining research trends and focal areas. Such analysis has been hampered because of difficulty accessing data and because the Caribbean, like most of the developing world, has not sought to document its scientific output.

Lalor (lo), who focused mainly on Jamaican scientists, was the first to at- tempt a systematic analysis of research productivity. To do this, he accessed SCI- SEARCH Dialog File 94 and examined all the citations listed as coming from Jamaica during the period 1974-1977. He found that workers at the University of the West Indies contributed 87.5% of the 369 articles encountered, and that the medical sciences accounted for 54.8% of these. He also found a parallel dominance by the medical sci- ences in Trinidad and Tobago, even though the medical faculty presence there was small. Lalor did not analyze further the thematic content of the medical science publications encountered, but he did note that the most prolific authors had been trained or were working at one of the re- search units at the university that had been established and supported by the Medical Research Council of Great Britain. He also made the interesting observation that Jamaica’s number of authors to population ratio was higher than that of any other developing country except Singapore.

More recently, McGann carried out a series of interviews with researchers in the Caribbean to establish some of the factors affecting health research (II). She found that while a large number of peo- ple in the health field claimed to be in- volved in research, there was no corre- lation between their numbers and the

number of publications produced. Fur- thermore, explicit national research pol- icies were seldom found; lack of time and resources were cited as the main con- straints on production; and even within the university setting there was little evi- dence of organization of research. The nature of this study did not permit the gathering of good quantitative data on research output.

The investigation reported here was undertaken to fill some of the gaps iden- tified above. Designed partly to follow up on Lalor’s study, it also covered a con- siderable span of time (three 5-year pe- riods) in order to detect possible trends. This study focused exclusively on health sciences research in those three countries (Barbados, Jamaica, and Trinidad and To- bago) with branches of the Faculty of Medical Sciences of the University of the West Indies. Within this context, it ex- amined several aspects of scientific pro- duction, paying special attention to the degree of congruence between the prior- ity health areas designated by the Carib- bean Health Ministers and the topics that were the subjects of publication.

METHODS

The main source of data was SCI- SEARCH, an international multidiscipli- nary index to the literature of science, technology, biomedicine, and related dis- ciplines produced by the Institute for Sci- entific Information (ISI). SCISEARCH contains all the records published in the Science Citation Index (SCI), plus addi- tional records from the Current Contents series of publications. In all, SCISEARCH covers more than 4 500 scientific and technical journals.

To retrieve the data sought we selected a broad array of journal subject categories including all aspects of the behavioral sci-

ences, biochemistry, biology, the

biomedical sciences, the environmental

sciences, medicine, microbiology, phar- macology, psychiatry, psychology, and other germane sciences. This was done by using the Journal Subject Category’s

SC-prefix. All citations relevant to these subject categories were retrieved, and se- lective editing was then done by one ob- server in order to discard some of the records that clearly were not within the health sciences field. In some cases of doubt the original items were obtained and reviewed.

Data were limited to 15 years (1976- 1990). Titles that originated in the three study countries were selected using SCI-

SEARCH’s Geographic Location (GL)

prefix. The printed citation records pro- vided the following information: title, au- thor, corporate source,4 journal, lan- guage, type of publication, geographic location, and journal subject category.

The database entries were grouped into three 5-year periods; each entry included the following elements: (1) identification number; (2) country; (3) year of publi- cation; (4) author(s) (1 to 10 names per publication); (5) general classification (see topics l-4 below); (6) CCH priority areas (see below); (7) institution (e.g., Uni- versity of the West Indies, PAHO); (8) collaboration (e.g., coauthors affili- ated with institutions other than that of the first author); (9) publication site (i.e., whether published in a local Caribbean or foreign journal); and (10) document type (i.e., article, editorial, review, letter, meeting abstract, note).

Within element 5 (general classifica- tion) there were four subcategories, one of which (general medicine) had seven subsections. These subcategories and subsections were as follows:

1) General medicine

(1) Internal medicine-including subspecialties (e.g., cardiology, gastroenterology, etc.)

41nstitutional affiliation of the primary author.

106 Bulletin of PAHO 29(2j, 19%

2)

3)

4) (2)

(3) (4) (5) (6)

(7)

Surgery-including subspecial- ties and anesthesiology

Child health

Obstetrics and gynecology Psychiatry

Microbiology and immunology Pathology-including anatomi- cal pathology, hematology, and clinical chemistry

Experimental medicine and labora- tory research

Public health-including epide- miology, biostatistics, and health services research

Other (e.g., medical sociology, health economics)

Those published items dealing with one or more CCH priority areas were as- signed to the area that appeared most relevant, with the remaining items being assigned to the category “other.” The overall list of categories was as follows: (1) environmental health (including vec- tor control), (2) human resources devel- opment, (3) noncommunicable diseases, (4) strengthening health systems, (5) nu- trition, (6) maternal and child health, (7) acquired immunodeficiency syn- drome (AIDS), and (8) other.

Assignment of the selected titles to one or another category necessarily entailed a degree of arbitrary variation. To limit this as much as possible, the posting was done by a single person (G. A.). In some cases of particular difficulty a copy of the original publication was obtained and re- viewed.

into single authors and then consolidat- ing the names, so as to end up with a record for each author showing the num- ber of times he or she appeared as the first author of a listed item and also the number of tunes he or she appeared as one of the first 10 authors.

RESULTS

A total of 1 712 titles were found and analyzed. Table 1 shows the distribution of these by 5-year study period and coun- try. Overall, Jamaica was found to ac- count for 74.1% of the total. Also, a steady increase in output was found to span the three time periods-a phenomenon most marked in Barbados, where there was a

five-fold innease between 1976-1980 and 1986-1990.

Table 2 shows the title distribution ac- cording to the general classification of subject areas. Most of the entries (57% of the total) were found to pertain to the field of general medicine. Of the 383 titles (22% of the total) found to deal with ex- perimental medicine, few came from either Barbados or Trinidad and Tobago, a pre- ponderance (331) in both absolute and relative terms coming from Jamaica. However, Jamaican output in this area declined over the study period (from 117 titles in 1976-1980 to 99 in 1986-1990).

Regarding public health, Trinidad and Tobago had a large share of the public health titles (40%), probably as a result

Table 1. The numbers of titles found, by country of origin, in each of the three S-year study periods.

Country 1976-l 980 1981-1985 1986-1990 Total Barbados

Jamaica Trinidad and

Tobago Total

14 42 70 126 402 431 436 1 269 70 109 138 317 486 582 644 1 712

Table 2. The numbers of titles found, by subject and country of origin, in each of the study periods.

Country/area 1976-1980 1981-1985 1986-l 990 Total Barbados: 14 42 70 126

General medicine 8 25 55 88 Experimental medicine 2 5 1 8 Public health 3 10 14 27 Other 1 2 0 3

lamaica: 402 431 436 I 269

General medicine 220 262 255 737 Experimental medicine 117 115 99 331 Public health 36 33 60 129 Other 29 21 22 72

Trinidad and Tobago: 70 109 138 317

General medicine 28 53 77 158 Experimental medicine 15 8 21 44 Public health 25 46 35 106 Other 2 2 5 9

Total 486 582 644 1712

of the Caribbean Epidemiology Center’s presence there. In contrast to the decline in Jamaican titles on experimental med- icine, the number of Jamaican public health titles increased during the study period.

Table 3 distributes the 983 “general medicine” titles into that category’s seven subdivisions. As may be seen, the largest single group of Jamaican titles was in the area of internal medicine, with rela- tively large numbers also occurring in the child health, surgery, and pathology sub- divisions. In both Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, surgery accounted for the largest single number of titles, the second most favored categories being internal medicine in Barbados and obstetrics and gynecology in Trinidad and Tobago.

Table 4 shows how the study titles were distributed with respect to the fields des- ignated CCH priority areas by the Carib- bean Ministers of Health. The most strik- ing finding was that most (63.8%) of these titles dealt with topics outside those fields. This was true both for the 5-year periods before the Caribbean Coopera- tion in Health was launched in 1986 and for the ensuing 19861990 period. From 1981 onward, the CCH field consistently receiving the most attention was mater- nal and child health. In contrast, the numbers of titles dealing with environ- mental health, human resources devel- opment, and the strengthening of health

systems were disappointingly small. Be- cause of the relatively recent arrival of AIDS, titles on AIDS only started ap- Table 3. The numbers of general medical titles found, divided by

subtopics, in each of the three countries of origin.

Trinidad

Subtopic Barbados Jamaica and Tobago Total internal medicine 23 163 28 214 Surgery 34 137 39 210 Child health 11 142 19 172 Obstetrics and gynecology 3 66 34 103 Psychiatry 8 13 7 28 Microbiology/immunology 6 86 9 101 Pathology 3 130 22 155

Table 4. The numbers of titles found in each of the Caribbean Cooperation in Health (CCH) priority areas, by study period.

Priority area 1976-1980 1981-1985 1986-1990 Total Environmental

health 5 23 17 45 Human resources

development 3 1 3 7 Noncommunicable

diseases 33 48 62 143 Strengthening health

systems 1 7 14 22 Nutrition 64 44 58 166 Maternal and child

health 48 a3 89 220 AIDS 0 4 12 16 Other 332 372 389 1 093

Total 486 582 644 1 712

pearing in the 1981-1985 period, though they increased notably in 1986-1990.

The institutional origins of the study publications (the institutional affiliations of the primary authors as identified from the “corporate source” data entries in SCISEARCH) are shown in Table 5. Be- cause of multiple institutional affiliations, the totals in this table exceed the total numbers of publications in the database. Generally speaking, it appears that the University of the West Indies (UWI) was the major institutional contributor in all three countries. This predominance was especially marked in Jamaica, where only 89 (7.0%) of the publications came from government institutions. In Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago these respective government figures were 55 (43.7%) and 130 (41.0%), the number of government- related publications in Trinidad and To- bago actually exceeding that found in Jamaica, (As shall be seen, a number of the Jamaican publications actually in- volved both the university and govern- ment institutions.) The relatively high number of publications that came from PAHO staff members in Trinidad and To- bago (89, or 28.1%) was a reflection of the presence of the Caribbean Epide- miology Center. (PAHO staff members

in Jamaica were not similarly produc- tive.) The category “other” in Table 5 refers to primary authors affiliated with non-

UWI, nongovernment, non-PAHO re-

search institutes; to private individual re- searchers; or in some cases to authors located in the country whose primary institutional affiliation was outside the Caribbean.

Researchers in the Caribbean have the option of publishing in a domestic sci- entific journal or in the foreign scientific press; Table 6 shows where their works appeared. It should be noted that the term “domestic” refers exclusively to the West

Indian Medicul Journal,

since that was the only domestic journal indexed in the database we searched. Within the three 5-year study periods the percentage of titles published in this journal rose from 26.5% in 1976-1980 to 34.7% in 1981- 1985, but then remained about the same (34.8%) in the last period. Overall, dur- ing the 15 years examined approximately a third of the titles studied (32.4%) were published in this domestic source.The 10 people most frequently contrib- uting, as one of the first 10 authors, to the published items from each country are shown in Table 7. A particularly note- worthy feature of these data is the very

Table 5. The institutional affiliations of the study items’ first authors, by the items’ country of origin and study period.

Country PAHO UWI Government Other Barbados:

1976-1980 1981-1985 1986-1990

6 2

87

10

27 44

lamaica: 33 1 188

1976-1980 13 371

1981-I 985 11 408

1986-1990 9 409

55 3 18 34

89

26 15 48

Trinidad and Tobago: 89 164 730

1976-1980 31 27 16

1981-1985 30 48 56

1986-1990 28 89 58

Total 728 7 433 274

14 2 3

9

68 16 15 37 34 13

8

13

716

Table 6. The numbers of titles published in foreign and domestic journals, by country and study period.

Countrv 1976-1980 1981-1985 1986-1990 Total Barbados:

Domestic Foreign

)amaica: Domestic Foreign

Trinidad and Tobago:

Domestic Foreign

14 5 9 402 112 290

42 70 126

19 16 40 23 54 86 431 436 I 269 154 161 427 277 275 842 70 109 138 317 12 29 47 88 58 80 91 229 7Ot.d 486 582 644 1712

large number of items authored or co- authored by one person, G. R. Serjeant from Jamaica, whose total (203) was more

than the total listed contributions of all

the first 10 authors from Barbados com- bined and represented 11.9% of the 1 712 study titles. The table does not list the types of publications involved, but ref- erence to the original material shows that all of this author’s contributions, as well as all those of B. E. Serjeant, dealt with the single topic of sickle cell anemia.

A number of attempts were made to devise a contribution rating system that would assign differing numbers of points to authors depending on whether they appeared as the first author and the num- ber of other authors listed. However, we did not find a way to establish a logical format for this, and so Table 7 simply shows the number of times each person was the first author of an item and the number of times that person was one of the first 10 authors. As a general rule, those authors with fewer publications were more likely to appear as the first author of those items. Conversely, those authors contributing to large numbers of items were obviously working as a part of a team and thus tended to appear as first authors less often. For example, the author contributing to the most items (G. R. Serjeant) was the first author of

110 Bulletin

of

PAHO 29(2), 1995only 12.3% of those in which his name appeared as one of the first 10 authors.

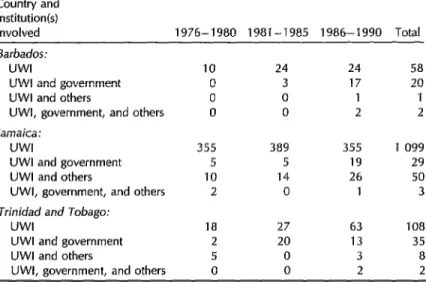

Table 8 shows the extent to which titles whose first authors were affiliated with the UWI involved extrainstitutional col- laboration with the government, other institutions, or both. There was evidence of substantial collaboration with govern- ment workers in Trinidad and Tobago (most notably during the 1981-1985 pe- riod) and in Barbados (primarily in 1986- 1990); but in Jamaica such collaboration was relatively rare. Indeed, the Jamaican researchers exhibited more collaboration with nongovernmental institutions (usu- ally foreign ones) than with government entities. (Extra-Caribbean collaboration was predominantly with workers in the United States and the United Kingdom.) Over the 15-year study period, on a per- centage basis, there was found to be a relatively high degree of extrainstitu- tional collaboration by workers in Bar- bados.

DISCUSSION

Table 7. The 10 people in each country who were most frequently listed as one of the first 10 authors of study items, showing the number of times each individual was listed as one of the first 10 authors and as the first author.

No. of publications where the individual

was listed as:

Country/author

Among the first 10 First authors author Barbados:

Everard, C.O.R. Shankar, K.B. Moseley, H. Nicholson, G.D. Fraser, H.S. Kumar, Y. St. John, M.A. Mahy, G.E. Hoyos, M.D. Everard, I.D. lamaica:

Serjeant, G.R. Golden, M.H.N. Jackson, A.A. Serjeant, B.E. Hanchard, B. Terry, S.I. Melville, C.N. Crell, G.A.C. Alleyne, G.A.O.

Grantham McGregor, S.M.

Trinidad and Tobago:

Roopnarinesingh, S. Naraynsingh, V. Raju, G.C. Bartholomew, C. Poonking, T. Tikasingh, E.S. Chadee, D.D. Miller, G.J. Jankey, N. Nathan, M.B.

21 11 19 14 18 6 15 7 15 8 13 13 8 5 8 6 8 7 8 8 203 25 80 23 61 20 50 5 49 8 38 15 37 9 36 17 34 7 33 17 34 21 33 18 31 17 24 16 22 0 19 7 18 16 14 11 14 1 13 11

ence, and indeed empirical observation over the years has shown that production has been essentially concentrated in these countries. The number of publications is- sued is a crude but accepted indicator of scientific activity, even though it tends to provide a less objective measure than

assessments based on reference citations (12-24).

The 15-year study period witnessed a steady increase in the overall number of titles, there being a 33% difference be- tween the first and third periods. The change was most marked in Barbados, which saw a five-fold increase from 1976- 1980 to 1986-1990.

There are no absolute measures or standards of comparison for publication rates; however, it has been claimed that in recent decades the growth of scientific literature as a whole has ranged between 2% and 3% per year (15). If so, this would place our observed increase for the Carib- bean within the average range, assuming that health literature has increased at the same rate as that of other sciences.

The publication rate relative to popu- lation size is sometimes used for inter- country comparison. When this is done, as Lalor has noted (ZO), Jamaican scien- tists compare very favorably with those of other countries. While such interna- tional comparison may not be valid, the quinquennial rate of title production per million population at the mid-period of our study (1981-1985) was approxi- mately the same in Barbados and Ja- maica, but much lower in Trinidad and Tobago (504, 577, and 288, respectively). Benzer et al. (16), analyzing medical pub- lications for 1990 with the use of an on- line database (EMBASE DIALOG), found annual production in the 20 leading countries to range from 819 titles per mil- lion inhabitants in Israel to 140 in Czech- oslovakia. (The United States recorded 526.) It is impossible to equate data from different bases; but we may make a crude calculation for Jamaica, which over the last 5-year period averaged 87 titles per year with an average population of 2.4 million. These figures suggest an annual rate of 36 titles per year per million in- habitants, equivalent to 7% of the U.S. figure.

Table 8. The numbers of study items indicating collaboration of UWI researchers with government and other institutions, by country of origin and study period.

Country and

institution(s)

involved 1976-1980 1981-1985 1986-1990 Total

Barbados:

UWI 10 24 24 58

UWI and government 0 3 17 20 UWI and others 0 0 1 1 UWI, government, and others 0 0 2 2 lamaica:

UWI 355 389 355 1 099 UWI and government 5 5 19 29 UWI and others 10 14 26 50 UWI, government, and others 2 0 1 3

Trinidad and Tobago:

UWI 18 27 63 108 UWI and government 2 20 13 35 UWI and others 5 0 3 8 UWI, government, and others 0 0 2 2

Kidd, in his analysis of medical re- search in Latin America, pointed out that there were three main determinants of scientific output in a country: the cultural milieu, political influences, and economic climate (27). There was no evidence of any major cultural shift over the study period, and in any case 15 years would be a very short period for experiencing such a shift. The political climate in the three countries was stable, in the sense that their forms of government did not change. However, marked political un- rest and violence in Jamaica during the 1970s led to a large-scale emigration of health and other professionals from that country. Despite this, the number of ti- tles from Jamaica exhibited an increase over the course of the study period.

Beyond this political difficulty, the Caribbean as a whole confronted severe economic problems during this period. As the economic situation worsened, both Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago expe- rienced declines in per capita GDP, a decline that Jamaica saw reflected in a significant fall in health expenditures

112 Bulletin of PAHO 29(2), 1995

(although in Trinidad and Tobago per capita health expenditure actually in- creased) (18). The economic downturn also created a precarious budgetary situation for the University of the West Indies as a whole-and particularly for the Uni- versity Hospital of the West Indies situ- ated in Jamaica, which entered a stage of chronic budget deficit due to nonpay- ment of government contributions. It is interesting to note that Barbados, which did not experience the economic diffi- culties of the other two countries, saw a much greater increase in scientific out- put. In theory, the fact that Jamaica main- tained its level of output might have re- sulted from the government protecting research funds in times of hardship or from most research not being funded by the government. The study data relating to the site of the research and the au- thors’ affiliations indicate that the latter situation prevailed.

distribution, shown in Table 2, is the rel- ative paucity of public health research in Jamaica compared with Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago, together with the relative predominance of experimental medical studies in Jamaica. The reasons for this, like many other results of this study, lie in the institutional arrange- ments that have developed in the Carib- bean. The LJWI Faculty of Medicine was established first in Jamaica, and the basic sciences were developed there. Later, clinical teaching was decentralized to in- clude Barbados and Trinidad and To- bago, but basic sciences remained in Ja- maica. Thus, the major thrust of research in the two smaller countries was clinical, with some attention also being given to public health. It is noteworthy that al- though the Department of Social and Pre- ventive Medicine and the graduate pro- grams in public health are predominantly in Jamaica, the latter country has pub- lished little public health research.

The presence of specialized institu- tional units also affects the nature of the different countries’ publications. The Tropical Metabolism Research Unit in Ja- maica is the only unit in the Caribbean dedicated specifically to metabolic re- search and experimental medicine, a fact clearly reflected by the publications in this field. Similarly, the presence of the Carib- bean Epidemiology Center in Trinidad and Tobago is reflected by the publications on public health from that country.

The dominant role of institutions may also be seen in the data on researchers who published the most. For example, 6 of the 10 researchers from Jamaica who had published the most either worked or had previously worked in one of the two aforementioned specialized units, the Tropical Metabolism Research Unit spe- cializing in nutrition or the MRC Well- come Laboratories that study sickle cell anemia exclusively. The groupings of tal- ent around specific research themes can

also be deduced from authorship pat- terns. In Jamaica, for example, G. R. Ser- jeant was the first author of only 25 out of the 203 publications to which he con- tributed, circumstances pointing to many collaborators engaged in a team effort, whereas in Barbados and Trinidad and Tobago first authorship was more com- mon among the more prolific research- ers. We should note here again that the most prolific Jamaican authors were in units that did not depend primarily on government funding for research sup- port, much of which came from foreign project grants or direct subventions.

The issue of how research policy and research efforts should relate to national health priorities is one that has been dis- cussed frequently in Latin America, the Caribbean, and other developing regions (4). A thesis heard repeatedly is that where the majority of the money comes from public funds, there should be some mechanism for ensuring that research is directed toward solution of the most pressing health problems. In fact, how- ever, much of the research in the devel- oping countries is directed toward prob- lems of the developed world and does not seek to reduce the large burden of disease that is often a consequence of and sometimes a contributor to underdevel- opment (2, 19).

In the Caribbean, the nearest approach to any research policy is to be found in the aims and objectives of the Common-

wealth Caribbean Medical Research

Council (CCMRC). This body, estab- lished in 1956 as the Standing Advisory Committee on Medical Research, became a council in 1972. Its major functions, as set forth in its constitution, are as fol- lows:

(a) to promote and coordinate medical research in the Commonwealth Caribbean; and

(b) to promote advice through the Conference of Ministries Respon- sible for Health to the participating governments on matters relating to research, including the needs and priorities appropriate to the area.

These mandates have been confirmed repeatedly and qualified in the sense of placing emphasis on strengthening re- search capabilities, focusing on the needs of the health services, and ensuring that results of the research are disseminated throughout the Caribbean. (Fraser has ar- gued that a more important task is to educate both governments and societies on the need for research “as a basic re- quirement for social action”-20.)

The closest approach to thematic prior- ities is to be found in those priority areas established by the Ministers Responsible for Health when the CCH Initiative was launched. (The first six priority areas were established in 1986 and AIDS was added later.) It could be argued that all but the last period covered by the study antedate the establishment of these priorities; but the priorities were defined on the basis of the countries’ epidemiologic profiles and their best judgements about the im- portance of areas that could not be effec- tively quantified and ranked through ep- idemiologic surveillance. Thus, we find areas such as strengthening of health sys- tems and human resource development included along with more categorical problem areas such as maternal and child health and AIDS. In general, it seems reasonable to assume that, with the ex- ception of AIDS, these priority areas must have had some degree of priority before and during the study period, especially since there is no evidence of any rapid change in the epidemiologic situation.

We found, however, that 63.8% of the study titles did not deal with any of the priority areas. Indeed, in an area as im- portant as strengthening health systems,

one including the important field of health services research, there were only 22 publications over the 15-year period. Those priority areas that received the most research attention were maternal and child health, food and nutrition, and chronic diseases. (AIDS, of course, did not ap- pear in the first period.)

This situation reflects a dilemma faced by many other countries. Specifically, re- search in the Caribbean is guided by two major factors-the initiative of the indi- vidual investigator and the broad theme of the specialized unit in which he or she works. Where there is not enough money to direct research toward priorities de- termined by the government, the inves- tigator seeks funding for topics of interest that have some chance of attracting funds. In the case of researchers who are not in special units, their work is usually an off- shoot of their daily clinical duties and does not consistently follow a specific line of inquiry. Sometimes, of course, both research units and individuals do wind up directing their attention to priority areas. For example, the Tropical Metab- olism Research Unit has focused mainly on the metabolic problems associated with childhood malnutrition, and its influence is seen in publications on both nutrition and maternal and child health.

Approximately one-third of the pub- lished items studied from each of the three countries had appeared domestically. It is possible that items with more original data would have been offered to foreign journals. Caribbean scientists probably share the same perceptions as others re- garding journals that are influential and that have the most impact in terms of their articles being most widely read and cited (22).

Overall, the most striking finding of this study was the major impact of insti- tutions upon scientific production in the three countries, as reflected by their clear influence in determining the quantity and

nature of the published items. In cbn- 9. trast, there was no indication that the quantity and nature of the published items reflected the priority areas established by the Ministers of Health.

1.

11.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

United Nations Development Program. Human development rqort, 1990. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Commission on Health Research for De- velopment. Health research: essential link to equity in development. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990.

Golden MHN. The importance of medical research in the Commonwealth Carib- bean. West Indian Med J 1988;37:193-200. Pan American Health Organization. Pali- ticas de investigacio’n en salud: documentos de la Conferencia Panamericana sobre Politicas de Investigaci6n en Salud (Caracas, 25-28 de abril de 2982). Washington, DC: PAHO; 1983. (Document PNSP/83-92).

Garcia JC. La investigacidn en el campo de Za salud en once paises de la America Latina. Washington, DC: Organizacibn Paname- ricana de la Salud; 1982.

Organizacibn Panamericana de la Salud. La invesfigacidn en salud en AmCrica Latina: estudio de paises seleccionados. Washington, DC: OF’S; 1993. 168 p. (Scientific publi- cation 543).

Inter-American Development Bank. Com- parative indicators of the results of sci- entific and technological research in Latin America. In: IDB. Economic and social prog- ress in Latin America, 1988 report. Wash- ington, DC: IDB; 1988.

Alleyne GAO. Medical research in the Caribbean. West lndian Med J 1980;29: 3-13.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

Pan American Health Organization. Car- ibbean cooperation in health. Washington, DC: PAHO; 1986. (XXII Pan American Sani- tary Conference, document CSP22/25). Lalor G. The productivity of Jamaican sci- entists. Jamaica J 1980;44:52-59.

McGann M. Report on the organization of science and technology in healfh research in the Caribbean. Washington, DC: Pan Ameri- can Health Organization; 1992. [Report to the Pan American Health Organization]. Fisher JC. Basic research in industry. Sci- ence 1959;129:1653-1657.

Westbrook JH. Identifying significant re- search. Science 1960;132:1229-1234. Garfield E. Volume 1: essays of an informa- tion scientist, 2962-1973. Philadelphia: IS1 Press; 1977.

Ziman JM. The proliferation of scientific literature: a natural process. Science 1980;208:369-371.

Benzer A, Pomaroli A, Hauffe H,

Schmutzhard E. Geographical analysis of medical publications in 1990. Lancet 1993;341:247.

Kidd CV. Biomedical research in Latin Amer- ica: background studies. Washington, DC: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1980. (NIH publication 80-2051). Pan American Health Organization. Health conditions in the Americas. 1990 ed. Wash- ington, DC: PAHO; 1991. (Scientific pub- lication 524).

United Nations Development Program, Task Force on Health Research for De- velopment. Essential national health re- search: a sfrategy for action in health and hu- man developmenf. New York: UNIX; 1991. Fraser HS. Developments in medicine and medical research in the Caribbean (1492- 1992). West Indian Med J 1992;41:49-52. Garfield E. Which medical journals have the greatest impact? Ann Intern Med 1986;105:313-320.