Brazilian

Journal

of

OTORHINOLARYNGOLOGY

www.bjorl.org

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Auditory-perceptual

analysis

of

voice

in

abused

children

and

adolescents

夽

,

夽夽

Luciene

Stivanin

a,∗,

Fernanda

Pontes

dos

Santos

a,

Christian

César

Cândido

de

Oliveira

a,

Bernardo

dos

Santos

b,c,

Simone

Tozzini

Ribeiro

a,

Sandra

Scivoletto

aaDepartmentandInstituteofPsychiatry,HospitaldasClínicas,FaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(FM-USP),São

Paulo,SP,Brazil

bInstituteofMathematicsandStatistics,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(USP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

cInstituteofPsychiatry,HospitaldasClínicas,FaculdadedeMedicina,UniversidadedeSãoPaulo(FM-USP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil

Received2September2013;accepted5August2014 Availableonline25November2014

KEYWORDS Childabuse; Voice;

Communication disorders; Childhealth

Abstract

Introduction:Abusedchildrenandadolescentsareexposed tofactorsthatcantrigger vocal changes.

Objective: Thisstudy aimedtoanalyze theprevalenceofvocalchanges inabusedchildren andadolescents,throughauditory-perceptualanalysisofvoiceandthestudyoftheassociation betweenvocalchanges,communicationdisorders,psychiatricdisorders,andglobalfunctioning.

Methods:This was anobservational and transversal study of136 children and adolescents (meanage10.2years,78 male)who wereassessedby amultidisciplinaryteamspecializing inabused populations.Speechevaluationwas performed(involving theaspects oforal and writtencommunication,aswellasauditory-perceptualanalysisofvoice,throughtheGRBASI scale).PsychiatricdiagnosiswasperformedinaccordancewiththeDSM-IVdiagnosticcriteria andbyapplyingtheK-SADS;globalfunctioningwasevaluatedbymeansoftheC-GASscale.

Results:Theprevalenceofvocalchangewas67.6%;ofthepatientswithvocalchanges,92.3% hadothercommunicationdisorders.Voicechangeswereassociatedwithalossofsevenpoints in global functioning,and therewas noassociation between vocalchanges andpsychiatric diagnosis.

夽 Pleasecitethisarticleas:StivaninL,dosSantosFP,deOliveiraCC,dosSantosB,RibeiroST,ScivolettoS.Auditory-perceptualanalysis

ofvoiceinabusedchildrenandadolescents.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2015;81:71---8.

夽夽

Institution:ProgramaEquilíbrio,DepartamentoeInstitutodePsiquiatriadoHospitaldasClinicas,FaculdadedeMedicinadaUniversidade deSãoPaulo(FM-USP),SãoPaulo,SP,Brazil.

∗Correspondingauthor.

E-mail:stivanin@usp.br(L.Stivanin). http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjorl.2014.11.006

Conclusion:Theprevalenceofvocalchangewasgreaterthanthatobservedinthegeneral pop-ulation,withsignificantassociationswithcommunicationdisordersandglobalfunctioning.The resultsdemonstratethatthesituationsthesechildrenexperiencecanintensifythetriggering ofabusivevocalbehaviorsandconsequently,ofvocalchanges.

© 2014Associac¸ãoBrasileira de Otorrinolaringologiae CirurgiaCérvico-Facial. Publishedby ElsevierEditoraLtda.Allrightsreserved.

PALAVRAS-CHAVE Maustratosinfantis; Voz;

Transtornosda comunicac¸ão; Saúdeinfantil

Análiseperceptivo-auditivadavozdecrianc¸aseadolescentesvítimasdemaustratos

Resumo

Introduc¸ão:Crianc¸aseadolescentesvítimasdemaustratosestãoexpostasafatoresquepodem desencadearalterac¸õesvocais.

Objetivo:Analisar a prevalência de alterac¸ão vocal nesta populac¸ão realizando análise perceptivo-auditiva da voz e estudar a associac¸ão entre alterac¸ão vocal, transtornos da comunicac¸ão,transtornopsiquiátricoefuncionamentoglobal.

Método: Estudoobservacionaletransversal.Participaram136sujeitos,comidademédiade 10,2anos,atendidosporequipemultidisciplinarespecializadanotratamentoambulatorialde vítimasdemaustratos.Foirealizadaavaliac¸ãofonoaudiologia(aspectosdacomunicac¸ãooral eescritaeanáliseperceptivo-auditivadavozaqualfoifeitapormeiodaescalaGRBASI).O diagnósticopsiquiátricofoidadodeacordocomoscritériosdiagnósticosdaCID-10eaplicac¸ão doK-SADS;ofuncionamentoglobalfoiavaliadopormeiodaescalaC-GAS.

Resultados: Aprevalênciadealterac¸ãovocalfoide67,6%,dospacientescomalterac¸ãovocal, 92,3%apresentaramoutrostranstornosdacomunicac¸ão.Aalterac¸ãovocalestáassociadaaum prejuízodesetepontosnofuncionamentoglobalenãoapresentouassociac¸ãocomtranstorno psiquiátrico.

Conclusão:A prevalênciade alterac¸õesvocaisencontrada foi maiordoqueaobservadana populac¸ãogeral, comassociac¸õessignificantescomtranstornos dacomunicac¸ãoe funciona-mentoglobal.Assituac¸õesqueestascrianc¸asvivempodemintensificarodesencadeamentode comportamentosvocaisabusivoseconsequentementedealterac¸õesvocais.

©2014Associac¸ãoBrasileira deOtorrinolaringologiaeCirurgiaCérvico-Facial.Publicadopor ElsevierEditoraLtda.Todososdireitosreservados.

Introduction

Violence against children and adolescents is considered to be a public health problem due to the many nega-tiveconsequencestobiopsychosocialdevelopment,1suchas

internalizingandexternalizing problems,2,3 belowaverage

intellectual function,3 academic and school performance

impairment,4,5 aswell asoral andwritten communication

disorders.6,7

Orallanguage,oneofthemostelaborateformsofhuman

communication,allowsthechildtoorganizehis/her

percep-tions,acquireknowledge,andbuildmemories.Itprovides

notonlysocialinteraction,butalsothelearninganduseof

rulestoregulateone’sownbehaviorandemotionalstate.8

Orallanguageacquisitiondisorderscanimpairlearning9and

causesocial,emotional,andbehavioralproblems.10,11

Successful communication depends not only on the

content of what is said, but also on the manner and

attitudethat thespeaker assumes duringthe interaction.

Specifically,facialexpressionsandvocalmodulationsduring

oral emission convey the speaker’s emotional state and

intention.12Thus,theproductionandrecognitionofspecific

characteristics of the speaker contribute to effective

communication.

The voice is an innate neurophysiological function,

resultingfromasophisticatedmuscularprocessing.Through

itsflexibility,itactsasasensitiveindicatorofthespeaker’s

emotions, attitudes, physical condition, and sociocultural

role.13

Anydifficulty or alteration in vocal emission that

pre-vents natural voice production characterizes dysphonia,14

an increasinglycommonobservation,withaprevalence of

6%---37%.15---17

Genetic and environmental components influence the

onset of vocal symptoms in different ways: the genetic

effectismoderate,whiletheenvironmentaleffectsarethe

moreimportantfactorsintheonsetofdysphonia.18

The causes of dysphonia include premature birth;19

nasal obstruction;20 allergic pulmonary reactions, such as

asthma and bronchitis; gastroesophageal reflux; auditory

symptoms;16 and sleeping problems.21 The main cause,

however,isvocalabusebychildren,asindicatedbystudies

with dysphonic children (90.3%,22 45.2%,23 and 54.67%24).

Therapidandcontinuouscollisionofthevocalfoldsduring

phonationcausestraumatothemucosalcapillaries,edema,

andinitiatestheprocessofnoduleformation.Lesionssuch

as cysts, sulci, paralysis, and papillomatosis may also

Knowing that voicechanges in childhood can interfere

withemotionaldevelopmentandsocializationofchildren,25

the identification and care of these disorders are

impor-tanttoallowfor thechild’sglobal functioning,helpingto

promotephysicalandemotionalhealth.

Childhoodvictimsofabuseareexposedtosomefactors

relatedtodysphonia,astheygrowinenvironmentswhere

yelling is very common among adults. The street

experi-encealsobecomesanaggravatingfactor.Yellingveryoften

becomesawayofstandingupforoneselfinthefaceof

dif-ficulties,inadditiontothefactthat theseindividualsare

directlyexposedtoenvironmentalaggressions(from

pollu-tion toclimate aspects) and drug use. It is, therefore, a

populationmorelikelytoshowchangesinvocalpatterns.

The aim of this study was to assess the prevalence

of voice disorders in this population and the

associa-tionofthesechangeswithothercommunicationdisorders,

psychiatric disorders, and global functioning through the

auditory-perceptual analysisof voicein childrenand

ado-lescentsvictimsofabuse.

Methods

Across-sectional observational studywasconducted after

the approval of the Research EthicsCommittee, protocol

number4353.

The participants were 136 children and adolescents

treatedbetweenJanuary2010andJuly2012bya

multidisci-plinaryteamspecializinginoutpatienttreatmentofvictims

ofabuse.Thesechildrenarereferredtothisservicebythe

technicalstaffofthe shelterswhere theyliveor byChild

ProtectiveServices.Themeanageofparticipantswas10.2

years,and78%weremales.The criteriafor patient

inclu-sioninthestudy wereage6---18 years;at leastonesocial

diagnosis(Z55---Z65---Personswithpotentialhealthhazards

relatedtosocioeconomicandpsychosocialcircumstances),

accordingtotheInternationalClassificationofDiseases

(ICD-10),26andconsentfromtheguardianforparticipationinthe

research.

Thosewithneurologicalproblemsandpsychiatric

symp-tomsthatcouldimpairtheunderstandingoftheevaluation,

such as patients with delusions, were excluded. Patients

who were already undergoing speech therapy were also

excluded.

Forthespeechtherapy assessment,specific testswere

usedintheareasoforallanguage,27,28 writtenlanguage,29

andspeech.30Thediagnoseswereclassifiedasphonological

disorders, alteration of semantic-syntactic skills, changes

inpragmaticcapacities,receptive-expressivelanguage

dis-order,writtenlanguagedisorder,articulationdisorder,and

dysfluency.

Forvoiceanalysis,samplesofspontaneousspeechwere

collected,aswellasofconnectedspeech,vocalemissions,

andsingingvoice,recordedonadigitalrecorder;oralmotor

assessmentwasalsoperformed.Clearandsimplelanguage

wasusedtoassessthechild/adolescent,andtheprocedure

wasexemplifiedtofacilitatethetestunderstanding.

Several times, more than one speech sample was

col-lected,toensurethesubsequentanalysis.Speechsamples

were submitted to auditory-perceptual analysis by

audi-ologists using the GRBAS31 scale, which characterizes the

patternofchange,tobeclassifiedas0(nodysphonia)and

1,2,and3(presenceofdysphonia).TheJapaneseGRBASI

scale,usedinternationally,isacompactandreliablemethod

ofassessingtheglobaldegreeofdysphonia(G)by

identify-ingkeyfactorswhendefiningadysphonicvoice:roughness

(R),breathiness(B),asthenia(A),strain(S),andinstability

(I).Forgreater data reliability,two other speech

pathol-ogistsspecializedinvoicewereaskedtoparticipate.After

listeningtotherecordedmaterial,theycompletedthesame

evaluation protocol. Samples whose analyses showed no

agreementwereexcludedfromthesample.

Psychiatric diagnoses were made by psychiatrists

spe-cializedin child and adolescent psychiatry. The Schedule

for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age

Children/Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL)32 was

appliedanddisorderswereclassifiedaccordingtothe

DSM-IV.

TheChildren’sGlobalAssessmentScale(C-GAS)involves

clinicalappraisalofthegenerallevelofpatientfunctioning

basedontheirbehaviorathome,withthefamily,atschool,

withfriends andduringleisure activities in thelast three

months.The scores range from1 to 100, and scores >70

indicatenormality.33

Data

treatment

Adescriptiveanalysisoftheresultsregardingthe

percent-age of patients with voice disorders was performed, by

gender and age. Analyses of associations between vocal

changeandthepresenceofpsychiatricandcommunication

disordersweremeasuredthroughFisher’sexacttest.34

Com-parisonofmeasuresofglobalfunctioning(C-GAS)between

groups wasperformed usingtheKruskal---Wallis,35 andthe

posthocwasperformedusingtheWilcoxon-Mann---Whitney

testwithBonferronicorrectionformultiplecomparisons.All

analyseswereperformedusingSPSS,release14.36

Results

According to the auditory-perceptual analysis of voice,

67.6% (n=92) of the patients had vocal changes, 79.3%

(n=72)wereyoungerthan12years,and56.5%weremales.

Therewasnostatisticaldifferencebetweenthegroups of

malesandfemales(p=0.423).

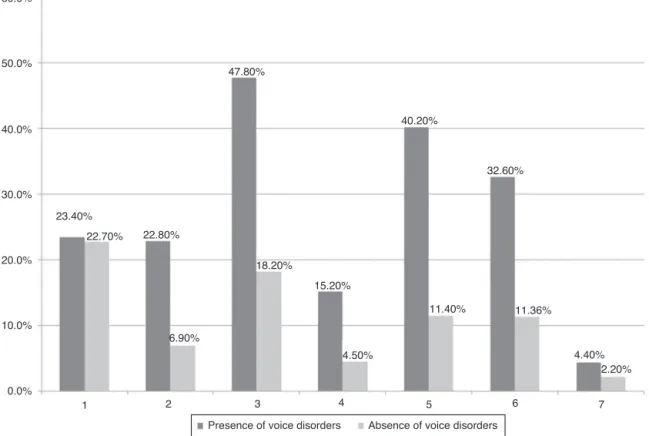

Mostsubjectswithvoicechanges(92.3%)alsohadother

communicationdisorders,asshowninFig.1.Theassociation

betweenthepresenceofvocalchange andcommunication

disorder was statistically significant in pragmatic

disor-ders(p=0.001), articulationdisorders(p=0.011),changes

insemantic-syntacticskills(p=0.029),receptive-expressive

language disorders (p=0.005), and written language

dis-order (p=0.000), indicating that individuals with these

disordersshowedahigherprevalenceofvoicechanges.The

pragmaticdisorder may increase the occurrence of vocal

changeby3.6-fold(p=0.004)andthephoneticdisorder,by

3.1-fold(p=0.034).

Fig.2showsthepercentageofpresenceandabsenceof

vocal disordersin psychiatricdisorders,distributedin the

most prevalent DSM-IV diagnostic categories in this

sam-ple. Although a higher proportion of voice changes was

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

11.40% 11.36%

4.40% 2.20% 4.50%

15.20%

32.60% 40.20%

18.20%

6.90% 22.80% 22.70%

23.40%

10.0% 20.0% 30.0% 40.0% 50.0% 60.0%

47.80%

0.0%

Absence of voice disorders Presence of voice disorders

Figure1 Associationbetweenvoicedisordersandotherdisordersoforalcommunicationin136childrenandadolescentvictimsof abuse(1,Phonologicaldisorder;2,Alterationinsemantic-syntacticskills;3,Alterationinpragmaticskill;4,Receptive-expressive languagedisorder;5,Writtenlanguagedisorder;6,Articulationdisorder;7,Speechdisfluency).

50.0%

45.0%

40.0%

35.0%

30.0%

25.0%

20.0%

15.0%

10.0%

5.0%

0.0%

F30 - F39 F70 - F79 F90 F91 F92 F98.0 - F98.1

14.10%

6.81%

20.50% 33.70%

14.10%

9.10%

4.30%

0%

10,90% 18,20% 36.40%

31.50%

Presence of voice disorders Absence of voice disorders

60.73

57.23

55.21

46.7 70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Without dysphonia and psychiatric disorder (n=15)

Only dysphonia (n=22)

Only psychiatric disorder (n=29)

Dysphonia + psychiatric disorder (n=70)

Figure3 Globalfunctioning(CGAS)ingroupsofchildrenwithvoiceand/orpsychiatricdisorders(n=136).

retardation,therewasnostatisticallysignificantassociation

between thesevariables (mood disorders,p=0.697;

men-talretardation,p=0.266;hyperkineticdisorders,p=0.159;

disordersofconduct,0.581;mixeddisordersofconductand

emotions,p=0.304;enuresisandencopresis ofnonorganic

origin,p=0.282).

To verify the subjects’ global functioning, they were

divided into four groups according to the presence or

absenceofvocalandpsychiatricdisorders.Themeanglobal

functioning(C-CGAS)foreachgroupwasbelowthelevelof

normalityandcanbeseeninFig.3.

The global functioning scoresof participants without a

disorder and in groups with vocal changes or psychiatric

disorderswerefoundtobebetween51and60,which

cor-responds to children with some problems in more than

one area. Participants who have voice changes and

psy-chiatric disorders have a global functioning in the range

41---50, which corresponds to children with obvious

prob-lems, deficits in most areas, or severe deficits in one

area. Statistical analysis showed no association between

voicechangesandpsychiatricdisorders(p=0.289)forglobal

functioning. However, the presence of voice change was

associatedwithalossofsevenpointsintheCGAS(p=0.002),

whereasthepresenceofapsychiatricdisorderwas

associ-atedwithalossof8.6points(p<0.001).

Discussion

The aimofthisstudy wastodetermine theprevalenceof

vocalchangesinchildrenandadolescentvictimsofabuse,

andto study theassociation between voicedisorders and

communicationandpsychiatricdisorders,aswellasglobal

functioning.

The results indicate a prevalence of voice disorders

higher than that observed in the general population;

higher prevalence of voice disorders in individuals with

communicationdisorders(significantassociation);no

signif-icant association between voicedisorders and psychiatric

disorders;andassociationbetween voicechangesandloss

ofsevenpointsinglobalfunctioning.

Weobservedahigherprevalenceofvoicedisordersthan

thatdescribedinstudiesonchildhooddysphonia,wherethe

prevalencerangesfrom6%to37%15---17;thissuggeststhatthe

factorstowhichchildrenandadolescentvictimsofabuseare

exposedmayincreasetheriskforthedevelopmentofvocal

disorders.

Deviantvocal behaviorisaformofinteraction,

aggres-sion,leadership,andawaytobecomeacceptedbyagroup,

andrepresentstheresultoftheinteractionofanatomical,

physiological,social,emotional,orenvironmentalfactors.37

One of the factors that couldtrigger voicechanges in

thisstudy populationwasthedisorganizedenvironmentin

whichtheylivedorstilllive.Familieswithtroubled

dynam-ics,crowded sheltersandlack ofindividualizedattention,

or even the streets, where the most efficient

communi-cationis notalways thesociallyaccepted type,arethree

riskfactorsfortheonsetofvocaldisorders.Theindividual

producesvocalmodulations thatarespecificforeachtype

of situation experienced (happiness, sadness, and anger,

amongothers)and environmentalfactors can causethem

tomake motor adjustments andchange the physiological

mechanisms,sothatthevoicemeetstheir needs.Studies

indicate that factors such as divorce, separation,

abnor-mal life conditions, too many adults in the environment,

impaired parent---child relationships, and unusual kinship

relationswereassociatedwiththeincidenceofdysphoniain

42%oftheassessedchildren.13 Childrenborntodepressed

mothersarelessresponsivetofacesandvoiceandinteract

lesswiththeirmothers.38

Ifthesechildren andadolescences need tochange the

vocal pattern tomeet their communication needs, it can

beinferredthatan impediment(whetherorganicor

func-tional)insomeaspectofmessagetransmissioncanworsen

thevocaldisorderandintensifyvoicechanges.Distortionsin

theproductionofspeechsoundsduetochangesinthe

posi-tionoftheteethinthedentalbite,inthetoneofthelips,

ofthephonoarticulatorytract,andcanalsocausevocal

dis-orders. Similarly, children with fewer language resources

tounderstand the environment and work out their needs

throughanefficientspeech,makeuseofothermeanssuch

asyelling, interrupting, crying, talking excessively,which

characterizesan abusive vocal behavior that alsotriggers

voicealterations.

Other disordersofcommunication, notassessed inthis

study,suchashearinglossandauditoryprocessing

difficul-ties,aremorecommoninchildrenandadolescentvictimsof

abuse,39whichpreventstheauditoryfeedbackoftheirown

speechandcausesdisordersinthevocalfoldmovement.

Althoughnoassociationwasobservedbetweenvocaland

psychiatricdisordersinthisstudy,itisknownthatabused

individualsexhibitcertaincharacteristics,suchaslow

self-esteem;lowtolerancetofrustration;difficultyestablishing

trustandattachment;andbehavioral,communication,and

interpersonal skill problems. Behaviors such as agitation,

motorrestlessness,impulsiveness,inattention,anxiety,and

insecuritylead toabusive and prolonged vocal behaviors,

suchastalkingtoomuchoratanincreasedspeechvelocity,

raisingthevocalintensity,yelling,andsuddenvocalattack,

whichoverloadstheapparatus.

For instance, a high-pitched voice may in some cases

reflecttensionintheintrinsicmusclesofthelarynx

result-ingfromanxietystates. Moreinsecureindividuals tend to

usea higher-pitched voiceand lowerintensity, word

pro-nunciationtendstobeimprecise,andtheynormallyusea

morerestricted voicemodulation, which cangive amore

monotonousspeech.40,41

Changesinbehavior,withphysicalandverbalaggression,

often appear to substitute the socially structured

behav-iorandcommunicationinchildrenandadolescentsatsocial

risk.Thisformofexpressionisessentialinthestreets,and

isoftenrelatedtosurvivalandanimportantpossibilityto

demonstratethefeelingsofbeingignoredbysociety---itis

awaytobeseenandheardin relationtotheirneedsand

desires.Moreover,inshelters,episodesofpsychomotor

agi-tation can beinterpreted asa clear sign of the need for

individualizedattention.Thus,onemustconsiderthatthis

typeofbehaviorandexpression,bothphysicalandverbal,

ispartoftheinteractionprocessofthesechildrenwiththe

worldaroundthemandthatithasitsrole.42

Therewasnodifferencebetweengendersforvoice

alter-ations, which differs from other studies that indicated a

prevalenceofvoicedisordersinboys.22---24,43,44 Researchers

highlight thatthe behavior of boysis more impulsiveand

aggressive than that of girls, who more typically exhibit

hyperactivity,anxiety,andleadership;themalebehaviour

when translated to the phonation mechanisms results in

vocalabuse.However,amongthepopulation ofvictimsof

abuse,girlsalsoneedtheabusiveuseofvoiceto

communi-cateandmeettheirneeds,whichcouldexplaintheabsence

ofgenderdifferencesinthisstudy.

Difficultiesin communication and behavioral and

emo-tional problems cause impairment of social skill,45,46 as

well as academic achievement and school engagement

limitations,47whichcharacterizesaglobalfunctioningthat

is below expectations. Although the vocal change has an

impact on overall health, on communication efficiency,

oneducationaland socialdevelopment,self-esteem,

self-image,andparticipationingroupactivities,48inthepresent

study a causal association between voice disorders and

globalfunctioningcouldnotbeinferred,giventhe

complex-ityoftheinvolvedfactors.

Anotherlimitationreferstothevocalassessmentused.

The scale used in the present study for the

auditory-perceptualanalysisofvoicewasemployedinother recent

studies andconsidered tobean excellent means ofvocal

assessment.16,49 However,theresearcherssuggestthe

per-formance of otorhinolaryngological examinationstoverify

thepresenceofvocalfoldlesions.

Martinsetal.24 identified57.5%ofvocal nodulesatthe

videolaryngoscopicassessment.Inthisstudy,patientswere

initiallyreferredtotheotorhinolaryngologyserviceof the

city health care network for examination and treatment,

ifnecessary.However,theauthorsdonothave theresults

of these evaluationsyet, which theyintendtoaddress in

afuturestudy.Anothersalientpointis thatthechildren’s

attitudesandthoseoftheirinterlocutorswerenotassessed

inthephysical, social/emotional,andfunctionaldomains.

Theauthorsindicatetheinclusionofsubjectivevoice

analy-sisthroughinterviewswithparents/tutorsandthechildren

themselves,inordertoincludespecifictechniquestoreduce

theabusivevocalbehavior.50

Conclusion

Childrenvictimsof abusehavea highprevalence ofvoice

disorders,mainlyassociatedwithcommunicationdisorders

and impaired global functioning. Characteristics of this

population, such as living in unsanitary places, disturbed

interpersonalrelationships,behavioralandemotional

prob-lems, and communication difficulties can constitute a

complex picture associated with abusive vocal behavior.

Otorhinolaryngologicalevaluation,aswellastheassessment

oftheattitudesofchildrenandcaregivers, shouldbe

con-sidered inordertocomplementthevocal assessment and

improvethemanagementofthispopulation.

Funding

This study was supported by Research Grant --- Fundac¸ão

FaculdadedeMedicina.

Conflicts

of

interest

Theauthorsdeclarenoconflictsofinterest.

References

1.Gilbert R, Widom CS, Browne K, Fergusson DM, Elspeth W, Janson S. Child maltreatment 1: burden and consequences of child maltreatment in high-income countries. Lancet. 2009;373:68---81.

2.TerrLC.Childhoodtraumas:anoutlineandoverview.JLifelong LearnPsychiatry.2013;1:323---33.

4.Sullivan PM, Knuston JF. The prevalence of disabilities and maltreatment among runaway children. Child Maltreatment Neglect.2000;24:1275---88.

5.PerlmanS,FantuzzoJ.Timingand influenceofearly experi-encesof child maltreatmentand homelessness onchildren’s educationalwell-being.ChildYouthServRev.2010;32:874---83. 6.EigstiIM, Cicchetti D.The impactof child maltreatment on

expressivesyntaxat60months.DevSci.2004;7:88---102. 7.StivaninL,OliveiraCCC,ScivolettoS.Levantamentopreliminar

de patologias na comunicac¸ão oral em crianc¸as e adoles-centesemsituac¸ãodevulnerabilidadesocial.In:16◦Congresso

BrasileirodeFonoaudiologia,CamposdoJordão,SP, Anaisdo congressoemCDR.2008.

8.Bolter NI, Cohen NJ. Language impairment and psychiatric comorbidities.PediatrClinNorthAm.2007;54:525---42. 9.BüttnerG,HasselhornM.Learningdisabilities:debateson

def-initions,causes,subtypes,andresponses.IntJDisDevEduc. 2011;58:75---87.

10.TommerdahlJ.Whatteachersofstudents withSEBDneedto knowaboutspeechandlanguagedifficulties.EmotBehav Diffi-cult.2009;14:19---31.

11.KreismanNV,JohnAB,KreismanBM,HallJW,CrandellCC. Psy-chosocialstatusofchildrenwithauditoryprocessingdisorder.J AmAcadAudiol.2012;23:222---33.

12.MostT,AmirN,DotanG,WeiselA.Auditoryandvisualaspects ofemotionproductionbychildrenandadults.JSpeechLang Pathol.2008;2:24---31.

13.Maia AA, Gama ACC, Michalick-Triginelli MF. Reac¸ão entre transtorno do déficit de atenc¸ão/hiperatividade, dinâmica familiar,disfoniaenódulovocalemcrianc¸as.RevCiênc Médi-cas.2006;15:379---89.

14.LeHucheF,AllaliAA.Voz:patologiavocaldeorigemfuncional. 2nded.PortoAlegre:ArtmedEditora;2005.

15.Carding PN, Roulstone S, Northstone K. The prevalence of childhood dysphonia: a cross-sectional study. J Voice. 2006;20:623---30.

16.TavaresELM, BrasolottoA, Santana MF, Padovan CA,Martins RHG.Epidemiologicalstudyofdysphoniain4---12year-old chil-dren.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol.2011;77:736---46.

17.TavaresELM,LabioRB,MartinsRHG.Normativestudyofvocal acousticparametersfromchildrenfrom4to12yearsofage withoutvocalsymptoms:apilotstudy.BrazJOtorhinolaryngol. 2010;76:485---90.

18.Nybacka I, Simberg S, Santtila P, Sala E, Sandnabba NK. Genetic and environmental effects on vocal symptoms and their intercorrelations. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2012;55: 541---53.

19.GartenL,SalmA,RosenfeldJ,WalchE,BührerC,HüsemanD. Dysphoniaat12monthscorrectedageinvery low-birth-weight-bornchildren.EurJPediatr.2011;170:469---75.

20.LabioRB,TavaresELM,AlvaradoRC,MartinsRLG.Consequences of chronic nasal obstruction on the laryngeal mucosa and voicequalityof4-to12-year-old children.JVoice.2012;26: 488---92.

21.BagnallAD,Dorrian J,FletcherA. Somevocal consequences ofsleepdeprivationandthepossibilityof‘‘fatigueproofing’’ the voice with voicecraft voice training. J Voice. 2011;25: 447---61.

22.AngelilloN,DiCostanzoB,AngelilloM,CostaG,BarillariMR, BarillariU.Epidemiologicalstudyonvocaldisordersinpediatric age.JPrevMedHyg.2008;49:1---5.

23.ConnellyA,ClementeWA,KubbaH.Managementofdysphonia inchildren.JLaryngolOtol.2009;123:642---7.

24.MartinsRHG,RibeiroH,MelloFMZ,BrancoA,TavaresELM. Dys-phoniainchildren.JVoice.2012;26:670---4.

25.MarkhamC,DeanT.Parents’andprofessionals’perceptionof qualityoflifeinchildrenwithspeechandlanguagedifficulty. IntJLangCommDis.2006;41:189---212.

26.Organizac¸ãoMundial daSaúdeClassificac¸ãointernacionaldas doenc¸as.10threv.PortoAlegre:ArtesMédicas;1992. 27.Andrade CRF, Béfi-Lopes DM, Fernandes FDM, Wertzner H.

ABFW: teste de linguagem infantil nas áreas de fonologia, vocabulário,fluênciaepragmática.Carapicuiba,SP:Pró-Fono; 2000.

28.Norbury C, Bishop D. Narrative skills of children with communication impairments.Int JLangComm Dis. 2003;38: 287---313.

29.SallesJF,ParenteMAMP.Relac¸ãoentreosprocessoscognitivos envolvidos na leitura de palavras e as habilidades de con-sciência fonológica em escolares.Pró-Fono RevAtual Cient. 2002;14:175---86.

30.BehlauM,PontesP.Avaliac¸ãoetratamentodasdisfonias.São Paulo:Lovise;1995.

31.FexS.Perceptualevaluation.JVoice.1992;6:155---8.

32.KaufmanJ,BirmaherB,BrentD,RaoU,FlynnC,MoreciP,etal. Scheduleforaffectivedisordersandschizophreniafor school-agechildren---presentandlifetimeversion(k-sads-pl):initial reliabilityandvaliditydata.JAmAcadChildAdolescPsychiatry. 1997;36:980---8.

33.ShafferD,Gould MS,BrasicJ,AmbrosiniP,Fisher P,Bird H, etal.Achildren’sGlobalAssessmentScale(CGAS).ArchGen Psychiatry.1983;40:1228---31.

34.AgrestiA. Categoricaldataanalysis.2nded.NewYork:John Wiley&Sons;2002.

35.ConoverWJ. Practicalnonparametric statistics.3rded.New York:JohnWiley&Sons;1999.

36.SPSSInc.SPSSforWindows.Version14.0.Chicago,IL:SPSSInc.; 2005.

37.HersanRCGP.Avaliac¸ãodevozemcrianc¸as.Pró-FonoRevAtual Cient.1991;3:3---9.

38.FieldT,DiegoM,Hernandez-ReifM.Depressedmothers’infants are less responsive to faces and voices. Infant Behav Dev. 2009;32:239---44.

39.ScarpariGK, Pontes F, OliveiraPA, Stivanin L, OliveiraCCC. Funcionamentoglobal,desempenhoneuropsicológicoe proces-samento auditivo em crianc¸as e adolescentes submetidas a maustratos.In:8◦ CongressoBrasileirodeCérebro,

Compor-tamentoeEmoc¸ões.2012.

40.Roy N, Holt KI, Redmond S, Muntz H. Behavioral character-istics of childrenwith vocalfold nodules. JVoice. 2007;21: 157---68.

41.Takeshita TK, Ricz LA, Isaac ML, Ricz H, Lima WA. Com-portamento vocal de crianc¸as em idadepré-escolar. Arq Int Otorrinolaringol.2009;13:252---8.

42.Scivoletto S, Stivanin L, Ribeiro ST, Oliveira CCC. Avaliac¸ão diagnósticadecrianc¸aseadolescentesemsituac¸ãode vulner-abilidadeeriscosocial:transtornodeconduta,transtornosde comunicac¸ãooutranstornosdoambiente?RevPsiquiatrClín. 2009;36:206---7.

43.Martins RHG, Trindade SHK. A crianc¸a disfônica: diagnós-tico,tratamentoeevoluc¸ãoclínica.RevBrasOtorrinolaringol. 2003;69:801---6.

44.KiliMA,OkurE,YildirimI,GuzelsoyS.Theprevalenceofvocal foldnodulesinschoolagechildren.IntJPediatr Otorhinolaryn-gol.2004;68:409---12.

45.CarlinoFC, Del PretteA, Abramides DVM.Avaliac¸ãodo grau deinteligibilidadedefaladecrianc¸ascomdesviofonológico: implicac¸ões nas habilidades sociais. Rev CEFAC. 2011: 1---7.

46.DelPretteZAP,RochaMM,SilvaresEFM,DelPretteA.Socialskills and psychologicaldisorders: convergingand criterion-related validityforYSRandIHSA-Del-Pretteinadolescentsatrisk.Univ Psychol.2012;11:941---55.

48.Connor NP, Cohen SB, Theis SM, Thibeault SL, Heatley DG, Bless DM. Attitudes of children with dysphonia. J Voice. 2008;22:197---209.

49.Simões-Zenari M,NemrK, Behlau M.Voicedisordersin chil-dren and its relationship with auditory, acoustic and vocal

behaviorparameter. IntJPediatr Otorhinolaryngol.2012;76: 896---900.