Populism by the people: An analysis of online comments in

Portugal and Spain

∗

Belén Fernández-García

Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Prof. Aníbal Bettencourt 9, 1600-189 Lisboa, Portugal

belen.garcia@ics.ulisboa.pt

Susana Salgado

Instituto de Ciências Sociais, Universidade de Lisboa, Av. Prof. Aníbal Bettencourt 9, 1600-189 Lisboa, Portugal

susana.salgado@ics.ulisboa.pt

ABSTRACT

There exists a gap in research on populism which tends to focus on politicians rather than on the people. This research addresses that by assessing the prevalence of populism and analyses citizens’ populist discourse in online comments in Portugal and Spain. The methodological approach is based on quantitative content analysis and co-occurrence textual analysis. The main findings point to a similar salience of anti-elitism in both countries, despite the differ-ent levels of electoral success of populist parties. These findings suggest that more attention should be paid to the views of citizens in populism research.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Human-centered computing; • Law, social and behavioral sciences; • Document management and text processing; • Vi-sualization;

KEYWORDS

Populism, People, Online comments, Content analysis

ACM Reference Format:

Belén Fernández-García and Susana Salgado. 2020. Populism by the people: An analysis of online comments in Portugal and Spain. In International Conference on Social Media and Society (SMSociety ’20), July 22–24, 2020, Toronto, ON, Canada. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 10 pages. https://doi.org/ 10.1145/3400806.3400831

1

INTRODUCTION

This research investigates whether and how citizens use populist rhetoric and claims in online opinion spaces. More specifically it identifies and measures the prevalence of specific features of populist discourse in the readers’ comments on news items. It also provides further analysis of the context in which citizens engage in populist rhetoric themselves. Our research approach is based on the assumption that citizens can engage in populist political discourse and to some extent even influence debates with populist positions, and that this engagement and influence is in ways similar to what has already been demonstrated for political parties and

∗This research was funded by the Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology

(FCT references: IF/01451/2014/CP1239/CT0004; PTDC/CPO-CPO/28495/2017).

SMSociety ’20, July 22–24, 2020, Toronto, ON, Canada © 2020 Copyright held by the owner/author(s). ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-7688-4/20/07. https://doi.org/10.1145/3400806.3400831

politicians. Most research that deals with populist discourse studies the communication style of populist politicians and parties [10, 16]; the spread of populism by or through the media [14, 17, 22]; or the adoption of populist elements by non-populist or mainstream political actors [5, 15, 24]. Conversely, research on how populist ideas are constructed and communicated by the people is not as developed [6]. Our research addresses this gap by investigating how populist ideas are constructed and communicated by the wider public in online comments.

Methodologically, the study relies on content analysis of news-readers’ comments in the two main newspapers (one representing the centre-right and the other the centre-left) from each country. Recent technological developments have consolidated the role of news media outlets as providers of spaces in which citizens can discuss public affairs [19], and these online spaces have emerged as opinion platforms that also serve important political participation functions. The analysis was divided into two parts: first, a quantita-tive content analysis examined the prevalence of specific features of populism in a sample of comments; second, a co-occurrence textual analysis traced the connections between the targets of populist rhetoric (e.g., politicians, immigrants, etc.) and the characteristics that news commenters had assigned to those targets (e.g., dishonest, illegal, etc.), as well as the issues that were framed using populist discourse (e.g., corruption, immigration).

2

METHODOLOGY

We analyse the prevalence of populism and its constituent elements and rhetoric in reader comments posted in four online newspapers: Público and Observador in Portugal, and El País and El Mundo in Spain. Our main objective is to provide a systematic empirical analysis with potential to contribute to a better understanding of how populist ideas are constructed and communicated by the wider public. The selection of these two countries allows us to compare two cases that differ substantially in the electoral success of populist political parties and politicians. In recent years, Spain has witnessed the electoral breakthrough of both radical left wing (Podemos) and radical right wing populist parties (Vox), whereas populism is still a marginal phenomenon in the Portuguese’s party system. Extant research that addresses the presence of populism at the mass level tends to focus on countries where populism has already been electorally successful [1, 6, 13]. These ignores all the other countries and consequently limits further understanding of any pre-existing inclinations to create or take on populist interpretations of politics, and vote for populist parties, which might then impact on the supply side of populism. Comparing cases with different levels of success of populist parties should provide additional insight into

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs International 4.0 License.

the active role of citizens in populism and as to whether their views match with the views of populist parties in their countries or not. As explained above, the empirical approach was based on a two-step content analysis of the readers’ comments to news stories. The unit of analysis was each single comment to the news stories about three specific topics (the keywords were: ‘European Union’, ‘economy’ and ‘employment’) published in four newspapers with opposing political orientations in the two countries: El País and Público left wing); and El Mundo and Observador (centre-right wing). The data was collected using an algorithm written specifically [25] for the automated extraction of the online com-ments published in the selected newspapers in 2018 and 2019. The total sample analysed was composed of 2,004 comments: 1,004 from Portuguese and 1,000 from Spanish commentary sections.

The data was treated following strict data privacy guidelines: we only used data from the newspapers websites that was publicly available. Nevertheless, in order to align with best practices in pri-vacy and ethical norms recommended in the field of social sciences, all data/comments were anonymised and we did not analyse or retain any identification and personal information from news read-ers and usread-ers; in this way, the actual content of the comments was never linked to the identity of the user and commenter.

These comments were first manually coded by native language trained coders. The Portuguese coders analysed 1,004 comments related to 266 news stories (501 comments published on the Público newspaper website and 503 on the website of online paper Obser-vador) and the Spanish coders coded 1,000 comments related to 280 news stories (497 comments published on the El País news-paper website and 503 on the El Mundo newsnews-paper website). The variables included in the codebook were designed with the intent of covering the features that are most commonly associated to current forms of populism, the guiding ideology (right-wing vs. left-wing), and the tone of the comments. The predominant tone of the comment was coded to one of the following options: ‘antagonis-tic’, ‘neutral or ambivalent’, ‘praise’. Coders indicated the presence of hate and insult by assigning a dichotomous option of ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The main political orientation was coded as: ‘right wing’, ‘left wing’, or ‘impossible to determine’. Finally, a set of dichotomous variables (yes/no) were aimed at measuring the prevalence of dif-ferent dimensions of populism: i) People-centrism; ii) Anti-elitism; iii) Anti-system; iv) Manichaeism where the division is ‘us versus them’); v) Manichaeism where the division is any other duality (e.g., good versus bad; right versus wrong; evil versus pure; etc.); vi) Expression of blame shifting and scapegoating; and vii) Ideal nation.

Such an approach to the study of populism takes into account the fact that there is not a fixed, common set of features that is always present in all of the social and political actors that are con-sidered populist. It acknowledges that populism, as a set of features present in discourses, is versatile enough to be occasionally used as a strategy by non-populist actors to serve specific purposes [24]. This means that political parties, politicians, social and political movements, citizens, and still other may be considered populist without necessarily sharing the exact same characteristics. Proof of this is the fact that in addition to the well-known radical right-wing and radical left-wing populist political parties and politicians, there are also centrist populists. More than just an ideology that simply

upholds the centrism of people (being the actual composition of ‘the people’, different according to different populists), it could be understood as a specific logic that determines ways of thinking and acting in politics [2, 12]. Extant empirical research has however already demonstrated that populism encompasses a few specific features [11] through which it is possible to ascertain its prevalence in the political discourse of different types of actors. We thus pro-pose to assess the prevalence of these previously acknowledged features of populism in online comments by citizens.

Manual coding allowed the identification of the comments con-taining populist features and the assessment of the prevalence of the different features. Comments were then further analysed through a co-occurrence textual analytical approach to detect the most recurrent combinations of words and topics used in the populist comments. This analysis was based on a semi-automatic content analysis using software KH Coder1. The co-occurrence network analysis was carried out to identify similar appearance patterns in the comments containing populism. This type of analysis provides a diagram that shows words with high degrees of co-occurrence [9]. In our case, the co-occurrence analysis was employed to trace the connections between the target groups of populist discourses by the citizen commenters (e.g., politicians, immigrants, etc.), the char-acteristics that they have assigned to those targets (e.g., dishonest, illegal, etc.), as well as the issues that were most commonly framed using a populist logic or rhetoric (e.g., corruption, poverty, immi-gration, etc.). That is, the main objectives of this part of the analysis were to identify discursive patterns in the populist discourse by the people (in this case, citizens commenting in online spaces), and to check the existence of patterns in the similarities and differences between Portugal and Spain. The combination of both quantitative and qualitative analyses in the same research design is meant to offer a closer examination of populism, as it is expressed by ‘the people’.

Technically, the diagrams followed the same criteria and steps in both countries. First, we have cleaned the dataset by removing stop words. These are commonly used words such as determinants, prepositions or coordinating conjunctions that do not offer any contribution for investigating the topic at hand (populism). In a second stage, the data was further prepared for analysis using the software KH Coder’s ‘pre-processing’ command that segments sen-tences into words and organizes these results as a database. Then, some filtering criteria were adopted in order to display only those edges representing strong co-occurrences. Technically, these crite-ria may vary according to the sample size and the heterogeneity of the text content. For our study, we have adopted the following criteria: i) the number of edges was limited to the 60 edges with the strongest Jaccard coefficients2(i.e., edges filtering by top 60, the option that appears by default in the software); ii) the words were also filtered by their minimal frequency of occurrence so that only those that appeared at least eight times were represented in the diagrams (i.e., filtering by minimum term frequency: 8); iii) verbs were excluded from the diagrams. These decisions were made to ensure the representation of the most significant co-occurrences

1https://khcoder.net/en/

2The Jaccard coefficient emphasizes whether or not specific words co-occur, i.e., it is

of words, essentially trying to balance parsimony and comprehen-siveness in the analysis approach. Nevertheless, to ensure that such decisions had not affected the final results, we have also created different diagrams using other filtering criteria to simulate other possibilities and check the validity of our findings. By the same token, we have performed a parallel analysis of the most recurrent terms in order to verify that the words that were in fact the most frequent and significant were being accurately represented in the final diagrams. The main co-occurrences represented in the final diagrams were produced by combining different filtering decisions that only affected the number of edges represented, which means that the same results were obtained using different filter criteria, changing only the number of edges that appeared in the graphics. When more flexible criteria are used, more edges and words appear, but when they are stricter, the diagrams become simpler.

3

POPULISM BY THE PEOPLE

3.1

Prevalence of features of populism in

online comments

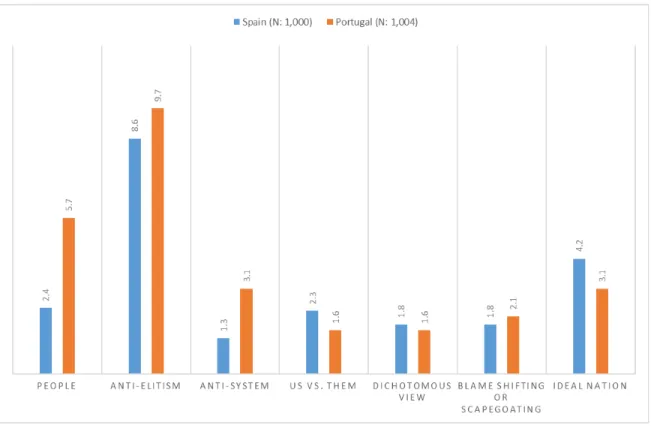

As Figure 1 shows, the Portuguese and Spanish comments that were analysed presented very similar levels of populism. In total, 19.8 per-cent (Portugal) and 18 perper-cent (Spain) of the comments published on the newspapers’ websites contained some kind of populist features in each of these two countries. The most recurrent populist element in both countries was anti-elitism (9.7 percent of the comments in Portugal and 8.6 percent in Spain). The second most frequent populist features were ‘reference to the people’ in Portugal (5.7 percent) and the ‘ideal nation’ in Spain (4.2 percent). The remaining dimensions of populism have a similar distribution in the two coun-tries, with a slight difference found in the ‘anti-system’ references, which were more frequent in the Portuguese than in the Spanish comments. The expressions of blame shifting and scapegoating were also slightly more common in the Portuguese comments than in the Spanish comments (2.1 percent and 1.8 percent, respectively). Conversely, the ‘us versus them’ approaches to politics were more prevalent (2.3 percent) in the Spanish comments than in the Por-tuguese comments (1.6 percent), while other types of dichotomous views of politics and society were present in almost the same per-centage in the comments from both countries (1.8 percent in Spain and 1.6 percent in Portugal).

In both countries, populism by the people is more frequent in the comments published on the centre-right newspapers’ websites (23.5 percent in Observador and 20.1 percent in El Mundo) than on the centre-left newspapers’ websites (16.2 percent in Público and 15.9 percent in El País). Populist comments expressing right-wing positions (27.2 percent in Spain and 12.6 percent in Portugal) were also more prevalent than comments expressing left-wing positions (12.8 percent in Spain and 8.5 percent in Portugal). However, it is important to note that right-wing comments almost double those of the left-wing in both countries. When considering the distribu-tion within ideological categories, populism is higher in left-wing comments in Portugal in proportional terms (44.7 percent of the comments identified as expressing a leftist position were populist) than in those coded as displaying a right-wing ideological position (30.5 percent). In Spain, the differences were less pronounced (40.4 percent and 42.2 percent, respectively).

Although without very distinctive patterns, it was possible to ob-serve that political orientation determined the type of populist fea-tures used in comments, but there are also noted cross-country dif-ferences. In Spain, left-wing positions were slightly more frequent than right-wing positions in comments containing anti-elitism (12 percent and 8.7 percent, respectively) and in comments display-ing people-centrism (13.6 percent and 11.1 percent, respectively), whereas in Portugal, left and right ideological stances are equally present in anti-elitism and people-centred comments. The ‘ideal nation’ approach offers a better-defined relation: over half of the comments coded as ‘ideal nation’ were also coded as right-wing (53.4 percent). Although it does also contain references against glob-alization in general, ‘ideal nation’, in the perspective of Portuguese and Spanish commenters, entailed mostly a negative view of multi-culturalism and immigration and the ideological positions which form the basis of exclusionary populism and nativism. The analysis thus confirmed that these views are mostly underpinned by views of the world inspired by the right-wing ideology. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that it was not possible to identify a clear ideological position in a considerable amount of these comments, which seems to suggest that immigration may be a key concern for most of these commenters regardless of their ideology. The rela-tion between anti-elitism, people-centrism and respective political orientation can be interpreted in a similar manner: between 75 to 79 percent of antagonistic comments that were critical of the elites and of the references to the people did not hold a clear political orientation and therefore did not entail an ideological distinction. This means that these could be cross-cutting views of politics, at least for these citizens.

Table 1 shows the cross tabulation between tone and populism. The analysis revealed that between 70 and 80 percent of the com-ments containing populism were also coded has having a negative or a politically antagonistic tone. In comments without any pop-ulism feature, the prevalence of political antagonism decreases by half. In addition to the negative tone, populist comments also had a greater prevalence of hate and insults (32.2 percent in Spain and 25.1 percent in Portugal) when compared to non-populist comments (19.6 percent and 7.2 percent, respectively). Although this type of analysis does not allow one to infer about the direction of the re-lation between these variables, the results clearly link populism and antagonism and suggest that populism may be an important driver and/or booster of uncivil behaviour and political negativism in online platforms used by citizens for comments and discussion.

3.2

Specific features of populism in Spanish

online comments

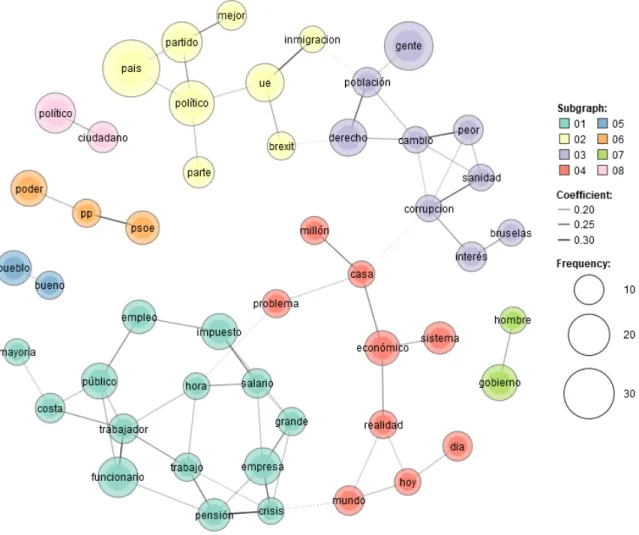

The diagram displaying the co-occurrence network of the Spanish populist comments (Figure 2) shows eight ‘communities’ of words (represented by different colors), that is, these are the “parts of the network that are more closely associated with each other” [9]. The most common words in the Spanish populist comments are ‘país’ (country), ‘España’ (Spain), ‘gente’ (people), ‘político’ (as the noun ‘politician’, and as the adjective ‘political’) and ‘funcionario’ (civil servant). These words, with the exception of ‘España’, represent the largest nodes in the diagram, and therefore the most frequently occurring words in our data. The largest node is ‘país’, which is

Figure 1: Prevalence of populist features in online comments by country (total of comments %) Table 1: Populism, tone and hate (%)

Populism Political tone(SP and PT***) Hate and insults(SP and PT***)

Populism Antagonistic Ambiguous/neutral Praise No Yes

Portugal No 39.8 56 4.2 92.8 7.2 (N: 1,004) Yes 81.4 15.6 3 74.9 25.1 Spain No 29.4 69.5 1.1 80.4 19.6 (N: 1,000) Yes 70 28.3 1.7 67.8 32.2 Total No 34.5 62.8 2.6 86.5 13.5 (N: 2,004) Yes 76 21.6 2.4 71.5 28.5 *** p-value Chi2 < 0.001

linked to ‘political’ ‘parties’, ‘EU’ and ‘immigration’. The thickest line3in this community of words is between ‘immigration’ and ‘EU’. In their comments, newsreaders often blame the European Union for destroying European countries’ identity and prosperity. They believe that there is an invasion or a deliberate plan to replace the native population with immigrants and refugees from non-European or Muslim countries.

In addition to the migration issue, the European Union and its member-countries also appear in other contexts, for example, as tar-gets of the attacks by those who oppose to the freedom of Catalan

3Thicker lines are used for stronger edges (co-occurrence) according to the values

reached by the Jaccard coefficient that measures the associations between words [9].

leaders (e.g., Puidgemont). Despite the frequent negativity associ-ated with the EU in our data, mentions relassoci-ated to ‘Europe’ are not always negative. When they are positive, ‘European Union’ or the ‘European countries’ are used as a moral reference in contrast to ‘our country’ (i.e., Spain), where ‘we’ have to deal with an ‘untrust-worthy’ political class”. For example, one comment refers to the comparison between “the corruption of our politicians with that of the rest of the EU countries. This basically means that the anti-political elitism found in the context of the European Union does not necessarily take the form of negative references against the European Union or European elites, but also appears as criticism of the behaviour of the national political elite within Spain. Finally, the edges connecting ‘political’ and ‘country’ also reveal comments

that express a radical anti-politicians discourse by which “politics is led the same scum in every country”.

The second largest node in the Spanish network is represented by the word ‘gente’ (people). In this set, the nodes ‘population’ and ‘people’ are also used in the context of anti-immigration discourses, as the ones described above (this explains why both communities are linked by two dotted lines). For example, some comments warn that “‘the people’ are not aware of the invasion by the Muslim ‘pop-ulation”’. The immigration of Muslims to Europe, which is described as “illegal” and “out of control”, threatens the ‘rights’ (‘derechos’) and prosperity of the Spaniards. In this type of commenting, pop-ulist radical right-wing parties and leaders (examples cited include Matteo Salvini, the political party Vox, or Marine Le Pen, among others) are positively valued as the only political actors that really defend the ‘interests of people’. A representative comment of this position is: “that is not called populism but common sense”. By contrast, what the commenters refer to as mainstream political actors, such as the French President Emmanuel Macron, and Albert Rivera, the former leader of Ciudadanos political party (both of whom are referred to in comments as “manufactured products”), are the main target of populist and hate comments – one comment noted that they only serve “the interests of people that we don’t know”.

In the same vein, the second most common element in this com-munity of words is the anti-political establishment discourse, sub-stantiated at different levels (the EU headquartered in Brussels, within the country Spain, in autonomous regions such as Andalu-sia, etc.) and linked to different topics and problems. Corruption and immigration are the main issues, but there are other important issues, such as ‘healthcare’. The antagonistic nature of the anti-establishment discourse becomes more pronounced in the edge that links the nodes ‘político’ and ‘ciudadano’ (‘citizen’), as demon-strated, for example, by the following comment: “traditional parties are not taking the concerns of ordinary citizens seriously”. The most frequent targets here are the Spanish mainstream parties, as shown by the edge connecting ‘PP-PSOE-poder’ (People’s Party-Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party-power). These two political parties (PP and PSOE) are blamed for their self-serving actions during the exercise of ‘power’, as the following comment illustrates: “in 35 years both PP and PSOE have done nothing and looked away while these poor devils (Catalans) were indoctrinated since their childhood, inocu-lating a hatred of Spain”. PP and PSOE are also criticized because “they only worry about holding on to ‘power”’. Additionally, some of the comments shown in this node contain attacks between PSOE and PP supporters, which indicates that the long-standing struggle between the two main parties in Spain is also present in the citizens’ comments and that supporters of non-populist parties (like PP and PSOE) can also engage in populist rhetoric and claims.

Although the anti-immigration discourse is highly prevalent in populist online comments (which partly explains why the variable “ideal nation” was the second most prevalent in Spain), immigrants and refugees are not the main targets when the comments also include insults and hate, except for those who are portrayed as “criminals”. The most frequent targets of insults and hate are politi-cians, political parties and the elites in general (e.g., expressions of disgust with “vote-buying politicians” (politicos compra-votos), “they think we are stupid”; “liars and incompetent politicians”). Civil

servants (‘funcionarios’) are also a common target of the attacks containing populism found in online comments; in fact, ‘funcionar-ios’ is one of the most frequent words in populist comments and is linked antagonistically to ‘trabajador’. Public sector workers are depicted in contrast to private sector workers that supposedly have worse working conditions and have to “work harder”, as opposed to ‘funcionarios’ who are considered “privileged people who have obtained their jobs through political favours and not through com-petitive and meritocratic processes”. Similarly to politicians, civil servants are viewed in an anti-system populist logic, as “system parasites”: “their privileges (e.g. their ‘pensions’) are paid at the expense (a ‘costa’ de) of the taxes and efforts of the majority” (‘may-oría’). The same frames that are applied to politicians and civil servants (“living at the expense of taxpayers” or “capitalizing on the effort of the majority”) are also used to describe large corpora-tions, banks, privileged social groups and the Catalan independence leaders.

A similar populist frame was found in the set of words that formed the node ‘economy’. In this case, the State and the “17 Reinos de Taifas” (the seventeen Spanish autonomous communi-ties) are considered “an unaffordable structure maintained with only through the (unbearable) economic effort of the people” and politicians are depicted in this node as servants of the economic sys-tem. In addition, comments blaming the European Union, specific governments, such as the US government, and the financial power for “destroying the country’s economic system” and for “worsening the people’s living conditions” were also found here. The ideological orientation of these comments varies from anti-neoliberal positions (e.g., “capitalists and the bourgeois social democrats don’t give a damn about the people”) to anti-left wing positions (e.g., “‘Podemi-tas’ and communists are a guarantee of misery, poverty, decay and totalitarianism”).

3.3

Specific features of populism in Portuguese

online comments

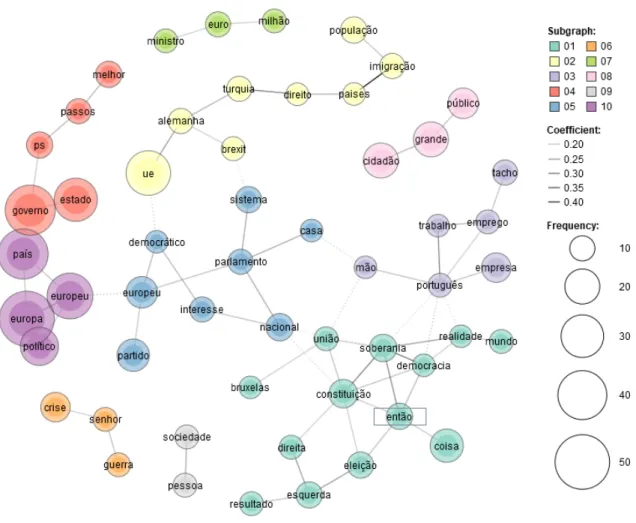

The co-occurrence network that resulted from the analysis of the Portuguese online comments displays ten word communities (Fig-ure 3). The most frequent words are ‘Povo’ (people), ‘Europa’ (Eu-rope), ‘Governo’ (Government), ‘País’ (country) and ‘UE’ (EU – European Union). As in the case of the Spanish comments, anti-elitism was the most prevalent element of populism found in the Portuguese comments, followed by “references and appeals to the people”. These populist features appear in different situations, but are predominantly related to the European Union and express a harsher tone than the Spanish comments. Most references to the European Union are characterized by an antagonistic discourse that opposes the interests of the Portuguese people (“our country” – in Portuguese “o nosso país”) to the ones of those who have been leading the “European project”. As the dotted lines show, references to Europe are made in different, but interconnected contexts. The largest node is ‘Europa’ (‘Europe’), closely linked to ‘país’ (‘coun-try’) and ‘político’ (politics and politicians).

4Filtering criteria: edges filtering by top 60 (i.e., number of edges with the strongest

Jaccard coeficients); words filtering by minimum term frequency: 8; thicker lines for stronger edges; verbs were excluded.

Figure 2: Co-occurrence network of words4: Spanish comments containing populism.

In large part, the criticism of the EU focuses on specific policy areas, such as foreign policy, the single currency (Euro) and the immigration policy. The European Union is the main target of the anti-elitism discourses, although some attacks to the national po-litical elite or to the government were also found in these online comments. The European Union is often described as a “global gov-ernment run by unelected elites”. Around the discourses focused on these elites are also a few conspiracy theories. These conspiracy theories included: the idea that the European project is a laboratory to test the “globalist theories” of world financial leaders like George Soros or secretive groups, such as the Bilderberg group; that mass immigration and the current migratory movements serve the in-terests of “pro-Soros lobbies”; and that the adoption of the Euro is part of “a globalist agenda” that seeks to destroy the independence and sovereignty of European countries. The belief that there is an invasion or a deliberate attempt by the elites to replace the native population with immigrants and refugees is depicted in the edge that links the words ‘immigration’ and ‘population’.

As in the citizens’ comments in Spain, most insults and expres-sions of hate are directed towards politicians and political institu-tions, but several insults against specific groups of immigrants were also found in the comments (e.g., “problematic and ignorant Islamic immigrants”). Concerns about immigration are also connected to ongoing debates in the EU, such as Turkey’s accession to the Euro-pean Union (e.g., “Europe will be invaded by a wave of millions of immigrants”) and Brexit (e.g., “Stop thinking like politicians and think like people who need more and better. YES TO BREXIT”). Such division seems to no longer represent the usual divide between left and right ideologies and their stances on immigration, but a divide between “those who want to populate Europe with peoples (‘povos’) with different cultures and ‘us’, the natives who have to pay the bill”.

Other frequent targets of populist rhetoric, antagonism and in-sults aimed against EU decisions and European political actors include Germany and Chancellor Angela Merkel, and to a lesser extent France and President Emmanuel Macron, both of which are described as the centre of power of the European Union and the ones that actually make all decisions and rule the other (subservient)

countries. This sentiment is demonstrated by comments such as “Europeans do not want a Europe at the behest of the central powers, Germany and France” and “they [Merkel and Macron] are noth-ing but fools servnoth-ing the financial powers that really govern”. The European political landscape is thus portrayed in an antagonistic manner and specific targets are clearly identified. Such identifica-tion of targets is not unrelated to the recent Eurozone crisis, which has resulted in Portuguese citizens having to endure a difficult pe-riod of austerity. The tough measures that were implemented in response to the crisis were the result of negotiations within the Eurogroup, but largely advocated publicly by the German Minister of Finance Wolfgang Schäuble [21].

The European Union is not only criticized for its policy orienta-tions and specific policies implemented in the member-states, but also for being “an undemocratic system” or an “illegitimate supra-national predator” that “instead of ruling in favour of the European peoples, actually rules against them”. Criticism of the European Union as a whole is depicted in the interconnected word communi-ties containing the nodes ‘parliament’, ‘constitution’, ‘sovereignty’ and ‘democracy’. The claims are related to the commenter’s inter-pretation of the modus operandi of EU institutions, which exclude the incorporation of direct inputs from citizens. This is represented in comments such as the following: “the people did not vote to enter the European Union”; “EU accession was an elitist process decided by politicians only”; and “the EU was an illegitimate and undemo-cratic project from its inception”. These comments also refer to the Portuguese Constitution, which “is very clear about Portugal’s sovereignty: it belongs to the people, therefore only the people can decide”. Under such framing of the EU, the European elections are considered to be “illegal and unconstitutional”; “the European elections are only good to politicians to get on the gravy train and have very well-paid jobs (“tachos e tachinhos bem remunerados”). In addition to being undemocratic, the European institutions are presented as having a hidden agenda and as serving the vested interests of the powerful (e.g., “the European Council is the biggest democratic fraud in history, it only serves to ensure hidden inter-ests decide against the will of the voters”). Consequently, if being against the EU and its institutions equals populism, “being populist is to be a democrat and reject the European totalitarianism”; i.e., to be “in favour of the people and against the elites”.

European ‘countries’ or ‘Europe’ are also often linked to the actions of the national government and to the state of the country’s economy in these comments. The EU and the national govern-ment are blamed for the country’s poor economic growth and for Portugal lagging behind the rest of Europe (e.g., “graças a eles con-tinuamos na cauda da Europa”-“thanks to them, we lag behind all other European countries”). Such interpretation is illustrated in the diagram through the community of words linking the nodes ‘governo’ (Government), ‘Estado’ (State) and ‘PS’ (Socialist Party). Populist discourse is thus aimed against the national political elites in power (incumbent government), who are “servants of the EU”. This group is sometimes insulted because of their dynamic with the EU, as in comments like the following: “this country is a par-adise for corrupts, thieves and opportunists”. The Socialist Party and some of its members (e.g., Prime Minister António Costa, MEP Pedro Marques) are the most frequent targets of these comments, but other mainstream parties with Parliamentary representation

(e.g., PSD, Social Democratic Party; CDS–People’s Party) and their leaders are also occasionally targeted, as part of the political elite that is “unresponsive and self-serving”.

Finally, the set of words containing the specific nodes ‘Português’ (Portuguese), ‘emprego’ (employment) and ‘trabalho’ (labour) also point to the salience of the criticisms of the government based on the state of the country’s economy. These comments are marked by an anti-capitalist stance and a ‘dedifferentiation’ discourse confirm-ing that there are no real differences between the main political parties, as illustrated by the following comment: “there is a cap-italist government that succeeds another capcap-italist government”. The incumbent socialist government led by Prime Minister An-tónio Costa, for example, is described as a “capitalist government” taking orders from “EU technocrats”, thus embodying the com-plete absence of the country’s economic sovereignty. In addition to the mainstream political parties and European Union institutions, bankers were also a target of populist attacks. As some of these comments state, “the Portuguese people have been paying for all the robberies (...) perpetuated by the banking system”; banks and bankers are described as “thieves” and “a risk for the Portuguese economy”.

4

DISCUSSION

Our research addresses a gap in extant literature by focusing on how populist ideas are constructed and communicated by the peo-ple. The advances in communication technologies have further democratized access to the public sphere, which means that com-mon citizens can now express their views more easily. These views can be taken as an expression of ‘the people’ and therefore it makes sense to examine them in the light of populism’s scholarly defini-tion. Our choice of countries also aims to bring some freshness to the topic, as most research on populism is focused on countries where populist political parties have experienced considerable elec-toral success. We argue that this approach emphasizes these actors at the expense of the actual views of ‘the people’. Finally, we study the people’s views empirically, thus paving the way for assessment of the operationalization of populist rhetoric by the people and not simply addressed to the people. If we are to take populist politicians’ rhetoric as them addressing the concerns and the needs of the real people, then to fully understand what substantiates such rhetoric we need to study the people’s discourse too.

In our attempt to work toward these objectives, we analysed the citizens’ populist discourse in online comments published on the websites of the two main daily newspapers in Spain and Portugal. These two countries illustrate different levels of electoral success of populist political parties and politicians and therefore make it particularly interesting to check the prevalence of populism at the grassroots level. Our approach and selection of countries allows a deeper understanding of populism on the demand side regardless of how it has emerged and has developed on the supply side, which also contributes to a better grasp of populism in general.

The first quantitative approach measured and compared the overall prevalence of populism and found that the levels of populist

5Filtering criteria: edges filtering by top 60 (i.e., number of edges with the strongest

Jaccard coeficients); words filtering by minimum term frequency: 8; thicker lines for stronger edges; verbs were excluded.

Figure 3: Co-occurrence network of words5: Portuguese comments containing populism.

discourse were very similar in the two countries: nearly 20 percent contained some type of populism in the two countries, with negative references to the elite being the most frequent element in both countries. References to the people were the second most prevalent feature of populism present in the Portuguese citizens’ comments, whereas in Spain it was the notion of an idealized nation (‘ideal nation’), which included negative references to globalization and positive references to nationalism and nativism. This feature (‘ideal nation’) was more common in Spain because in addition to the ongoing debate about the pros and cons of the immigration flows– also present in Portugal although to a lesser degree–Spaniards were also experiencing the “separatist” issue, particularly in Catalonia, and dealing with debates about the importance of the “unity of the nation”. This also partly explains why the word ‘España’ was one of the most frequent words in the comments. Additionally, the analysis showed that some of these characteristics appeared connected to each other: for example, negative comments on immigration and multiculturalism are frequently linked to critical stances towards the political elites in both countries. In most cases, this reveals that citizens blame political elites for current migratory pressures at the

national and European levels. Discussions about immigration are not simply framed as a difference between the left (pro immigration) and the right (against immigration), but more specifically as a divide between globalist positions and nationalist/nativist attitudes. A considerable number of the comments in our analysis (especially those expressing anti-elitism and people-centrism) did not hold a clear ideological distinction, which seems to suggest that populism does sustain a way of relating to politics that goes beyond the traditional right-left spectrum.

We also established a clear link between populism, antagonism and hate: in both countries, populist comments contained higher levels of political antagonism, hate and insults when compared to non-populist comments. This finding is in line with previous research that has shown that in addition to targeting elites, citizens’ populist discourse also tends to be hostile and uncivil [6, 22]. Pop-ulism may thus be a driver and/or a booster of uncivil behaviour and political negativism, at least in online platforms on which citizens express their views.

Populism, substantiated in its specific features present in these online comments, reflects the main concerns of these citizens and

the topics that are the most salient in each country at the time (the unity of the country in Spain and the economic growth–or the lack thereof–in Portugal). Nevertheless, we should also highlight impor-tant similarities between the two countries, namely: very similar levels of populism overall and a higher prevalence of anti-elitism in the citizens’ comments when compared to the other specific features of populism. The anti-elitism comments also target the same actors in Portugal and Spain: EU elites and national political elites in each country. In the case of anti-elitism directed towards political elites, both countries have recently experienced cases of corruption in politics that were brought to justice. In the case of the anti-elitism towards the EU institutions and elites, the picture is not as clear, as the image of the EU is more positive in Portugal than in Spain (in Spain 39 percent see the EU positively and in Portugal the percentage is 59). Moreover, citizens who tend not to trust in the EU are also more in Spain (51 percent) than in Portugal (33 percent) (Eurobarometer, Autumn 2019).

A similar prevalence of populism in online comments by citizens in countries that are so different in terms of the electoral success of populist parties is surprising, as one would expect populism to be less common in the country where populism has had less success in elections. In the most recent Spanish general election, held in November 2019, the sum of votes for populist parties – Podemos and Vox– was 28 percent, plus 6.8 percent of votes for Ciudadanos (initially considered a populist party by many due to its anti-establishment stance and that nowadays still engages in populist rhetoric occasionally). In the most recent election in Portu-gal, held in October 2019, the total percentage of votes for populist parties was 1.84 percent (the Enough–in Portuguese ‘Chega’–party had 1.29 percent of the votes and elected an MP, the National Re-newal Party had 0.33 percent and the Democratic Republican Party received 0.22 percent of the votes). The 1.84 percent of votes for pop-ulists in Portugal does not include the Communist Party (PCP) and the Left Block party (BE), which occasionally also engage in pop-ulist rhetoric; overall these parties are not considered completely populist. The votes for BE and PCP were 9.52 and 6.33, respectively. It can be argued that these two parties have managed to empty other radical left-wing populist proposals [20]. Research on other countries has revealed similar evidence of levels of populist atti-tudes among the electorate, resulting in different outcomes at the electoral level [8]. The competence (or lack of it) of populist politi-cal leaders to engage and convince voters is an important factor to take into account [23], as it is the actual national context in which elections are held. For example, the escalation of the separatist crisis in Spain could have contributed to activating or reinforcing pop-ulist attitudes of certain sectors of the Spanish right, which could explain Vox’s recent electoral successes [26], much like the Euro Crisis and the austerity measures implemented in some European countries had already boosted populism and the related political parties’ electoral success [3, 21].

It is interesting to note that in the case of Portugal the absence of a strong populist leader or political party infusing populist ideas into the Portuguese people did not translate into lower levels of populism in the citizens’ opinions expressed in online comments. Such a finding reinforces the idea that the general population does hold populist views regardless of the strength of populism in the

party system and of the levels of electoral success of populist par-ties. The absence of successful populist parties therefore may not be due to a lack of demand, but to the weak mobilization power of existing populist ideas among the electorate by populist political leaders. Extant research often looks at populism from the perspec-tive of strong political leadership and thus fails to acknowledge the broader picture, namely the contexts in which those leaders do convince voters and defeat their opponents. It is therefore im-portant to acknowledge and assess the pre-existing ideas and the views of citizens (‘the views of the people’). Often, citizens are portrayed as unthinking and easily moldable masses [27] that vote for populist political parties and politicians simply because they are not sophisticated voters and therefore do not understand the intricacies of political decisions. This line of thought asserts that populist parties and politicians communicate with citizens directly and offer simple solutions to complex problems, and thus easily convince them. Nevertheless, research has increasingly been chal-lenging the notion that voting for populists or holding populist views is associated with low levels of political competence [18]. Populist ideas can also originate from the people and subsequently be exploited by populist leaders that either think as the people, or make the people believe that they think like them. Our approach allows the systematic assessment of such views of the people, to the extent that these are reflected in the comments posted online by citizens.

Given that most of these populist views and narratives are not replicated in mainstream media, at least not identically to the origi-nal accounts, the online platforms represent an unique opportunity for citizens to voice their concerns and their interpretations of re-ality, which have only gained greater public visibility due to the emergence of such online spaces. More than simple amplifiers, the online spaces seem to be including a wider diversity of political views, including populism.

REFERENCES

[1] Sina Blassnig, Sven Engesser, Nicole Ernst and Frank Esser. 2019. Hitting a Nerve: Populist News Articles Lead to More Frequent and More Populist Reader Comments. Political Communication, 36, 4, 629–651.

[2] Benjamin De Cleen. 2019. The populist political logic and the analysis of the discursive construction of ‘the people’ and ‘the elite’. In Jan Zienkowski and Ruth Breeze (Eds.) Imagining the Peoples of Europe. Populist discourses across the political spectrum. John Benjamins Publishing Company, p. 19-42.

[3] Manuela Caiani and Paolo Graziano. 2019. Understanding varieties of populism in times of crises. West European Politics, 42, 6, 1141-1158.

[4] Johan Farkas, Jannick Schou and Christina Neumayer. 2018. Platformed antago-nism: racist discourses on fake Muslim Facebook pages. Critical Discourse Studies, 15, 5, 463-480.

[5] Belén Fernández-García, B. and Óscar G. Luengo. 2018. Populist parties in Western Europe. An analysis of the three core elements of populism. Communication & Society, 31, 3, 57-76.

[6] Michael Hameleers. 2019. The Populism of Online Communities: Constructing the Boundary Between “Blameless” People and ‘Culpable” Others’. Communication Culture & Critique, 12, 147–165.

[7] Michael Hameleers, M., Bos, L., Fawzi, N., Reinemann, C., Andreadis, I., Corbu, N., Schemer, C. Schulz, A., Shaefer, T., Aalberg, T., Axelsson, S., Berganza, R., Cre-monesi, C., Dahlberg, S., de Vreese, C. H., Hess, A., Kartsounidou, E., Kasprowicz, D., Matthes, J., Negrea-Busuioc, E., Ringdal, S., Salgado, S., Sanders, K., Schmuck, D., Stromback, J., Suiter,J., Boomgaarden, J. Tenenboim-Weinblatt, K., and Weiss-Yaniv, N. et al. 2018. Start Spreading the News: A Comparative Experiment on the Effects of Populist Communication on Political Engagement in Sixteen European Countries. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 23, 4, 517-538.

[8] Kirk A. Hawkins, Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser and Ioannis Andreadis. 2020. The Activation of Populist Attitudes. Government and Opposition, 55, 283–307. [9] Koichi Higuchi. 2016. KH Coder 3 Reference Manual, March 16. Available at:

[10] Gilles Ivaldi, et al. 2017. Varieties of Populism across a Left-Right Spectrum: The Case of the Front National, the Northern League, Podemos and Five Star Movement. Swiss Political Science Review, 23, 4, 354-376.

[11] Jan Jagers and Stefaan Walgrave. 2007. Populism as Political Communication Style: An Empirical Study of Political Parties’ Discourse in Belgium. European Journal of Political Research, 46, 3, 319–45.

[12] Michael Kazin. 1995. The Populist Persuasion. An American History. Ithaca and London, Cornell University Press.

[13] Michal Krzyżanowski and Per Ledin. 2017. Uncivility on the web. Populism in/and the borderline discourses of exclusion. Journal of Language and Politics, 16, 4, 566-581.

[14] Óscar G. Luengo and Belén Fernández-García. 2019. Campaign Coverage in Spain: Populism, Emerging Parties, and Personalization. In Susana Salgado (Ed.) Mediated Campaigns and Populism in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham, p. 99-121.

[15] Luke March. 2017. Left and right populism compared: The British case, The British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 19, 2, 282–303.

[16] Cas Mudde and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwasser. 2013. Exclusionary vs. Inclusionary Populism: Comparing Contemporary Europe and Latin America. Government and Opposition, 48, 2, 147–174.

[17] Matthijs Rooduijn. 2014. The Mesmerising Message: The Diffusion of Populism in Public Debates in Western European Media. Political Studies, 62, 726–744. [18] Guillem Rico, Marc Guinjoan and Eva Anduiza. 2019. Empowered and enraged:

Political efficacy, anger and support for populism in Europe. European Journal of Political Research, https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12374.

[19] Ian Rowe. 2015. Deliberation 2.0: Comparing the Deliberative Quality of Online News User Comments Across Platforms. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic

Media, 59, 4, 539-555.

[20] Susana Salgado. 2019. The 2015 Election News Coverage: Beyond the Populism Paradox, the Intrinsic Negativity of Political Campaigns in Portugal. In Susana Salgado (Ed.) Mediated Campaigns and Populism in Europe, Palgrave Macmillan, p. 75-98.

[21] Susana Salgado and Yannis Stavrakakis. 2019. Introduction: Populist discourses and political communication in southern Europe. European Political Science, 18, 1, 1-10.

[22] Susana Salgado. 2019. Where’s populism? Online media and the diffusion of populist discourses and styles in Portugal. European Political Science, 18, 1, 53-65. [23] Susana Salgado and José Pedro Zúquete. 2017. Portugal: discreet populisms amid unfavorable contexts and stigmatization. In Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Carsten Reinemann, Jesper Strömbäck, Claes de Vreese, (Eds.) Populist Political Communication in Europe. London & New York, Routledge, p. 235-248. [24] James Stanyer, Susana Salgado and Jesper Stromback. 2017. Populist Actors as

Communicators or Political Actors as Populist Communicators: A Cross-National Findings and Perspectives. In Toril Aalberg, Frank Esser, Carsten Reinemann, Jesper Strömbäck, Claes de Vreese, (Eds.) Populist Political Communication in Europe. London & New York, Routledge, p. 353-364.

[25] Diogo Torres and Susana Salgado. 2019. Algorithm for online infor-mation collection. Version 1. observador. py. (FCT Research Project: IF/01451/2014/CP1239/CT0004).

[26] Stuart J. Turnbull-Dugarte. 2019. Explaining the end of Spanish exceptionalism and electoral support for Vox. Research and Politics, 1-8.

[27] Susana Salgado. 2005. O poder da comunicação ou a comunicação do poder (The power of communication or the communication of power). Media & Jornalismo, 7, 79-94.