192 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 18, no. 2, 1984

search on development of a vaccine that could be produced in cell cultures; this latter would greatly improve the speed and possibly the economy of vaccine production and allow for rapid expansion of production in the event of emergency situations.

In response to these recommendations, Brazil and Colombia have improved the phy- sical facilities of their vaccine proddction laboratories using national funds. In addition, both laboratories are modernizing their vac-

cine production methods with funds made available by Canada’s International Develop- ment Research Center and the Canadian In- ternational Development Agency. A portion of these latter funds has also been provided to conduct research on thermostabilizing media for yellow fever vaccine.

Source: Pan American Health Organization (Epidemi- ology Unit, Health Programs Development), PAHO Epi- demiological Bulletin 4(6):7-10, 1983.

VACCINES USED IN THE EXPANDED PROGRAM ON

IMMUNIZATION (EPI): INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Introduction

Immunization is one of the most powerful and cost-effective weapons of modern medi- cine. Immunization services, however, re- main tragically underutilized in the world to- day. In developing countries, it can be ex- pected that some 0.5% of all newborns will become crippled from poliomyelitis, 1% will die from neonatal tetanus, 2% will die of per- tussis, and 3% will die from measles. In all, some five million children die from these dis- eases each year, 10 children with each passing minute.

These diseases are preventable with cur- rently available vaccines if children ca.n be im- munized early enough in childhood. There- fore, the decision to withhold the benefits of immunization from an eligible child, whatever the reason, should not be taken lightly. Unfor- tunately, health workers in many countries are faced with long lists of contraindications which, when followed scrupulously, result in many children remaining unimmunized. The problem resulting from deferring immuniza- tion is greatest where access to health services is limited and where the morbidity and mor- tality from vaccine-preventable diseases are

high. Immunization is frequently postponed if children are ill, malnourished, or about to be hospitalized; yet these are the very children for whom immunization services are most needed, for they are the ones most likely to die should they acquire a vaccine-preventable dis- ease.

The purpose of this work is to review the benefits and risks of routine immunization of children with BCG, DPT, measles, and polio- myelitis vaccines, and (particularly for ill and malnourished children) to suggest circum- stances in which immunization may be in the child’s best interest.

Adverse Reactions to Immunization

. ABSTRACTS AND REPORTS 193

tally related to a child’s illness. Convulsions, for example, may follow DPT or measles im- munization, but the background rate is high. At ages 3 to 15 months, the monthly incidence of convulsions ranges from 0.8 to 1.4 cases per 1,000 children (41-42).

BCG Immunization

The most serious complications of BCG im- munization are disseminated infection with the BCG bacillus and BCG osteitis (Table 1). Both of these complications are rate. The former is usually associated with severe abnor- malities of cellular immunity (12, 43), while the latter has been reported mainly among in- fants immunized in the neonatal period in the Scandinavian countries (3-5). The most com- mon complication, suppurative lymphade- nitis, has been reported in 0.1-4s of immu- nized children under two years of age. The risk of adverse reactions is related to the BCG strain used by different manufacturers, the dose, the age of the child, the method of im- munization, and the skill of the vaccinator.

DPT Immunization

The most severe complications following DPT immunization are neurologic and are thought to be due primarily to the pertussis component of the vaccine. A recent large study in the United Kingdom, the National Childhood Encephalopathy Study, reviewed the immunization histories of children two months to three years of age who were hospi-

Table 1. Estimated rates of adverse reaction

following BCG immunization.

Adverse reaction

Disseminated BCG infection Osteitis

Suppurative adenitis (among children < 2 years old)

Estimated adverse References

reaction rate per providing

100,ooo vaccinees data

<O.l 1-3 <O.l-30 2-5

200-4,300 3, 6-12

talized with serious acute neurologic illnesses (encephalitis/encephalopathy, prolonged con- vulsions, infantile spasms, and Reye’s syn- drome) and compared them with a control group (14, 44). It was estimated that a severe neurologic illness attributable to DPT oc- curred once in 110,000 DPT immunizations, and that lasting neurologic damage occurred once in 310,000 immunizati0ns.l The hazards of DPT immunization must, however, be bal- anced against the risks of remaining unimmu- nized. Convulsions, for example, occur 100 to 3,000 times more often during whooping cough than following DPT immunization, and pertussis frequently causes encephalo- pathy or death (Table 2).

Fever and mild local reactions following DPT immunization are common. It is esti- mated that 2-6% of the vaccinees develop a fever of 39% or higher, and that 5-10 % ex- perience swelling and induration or pain lasting more than 48 hours at the site of the in- jection. In studies in the United States and Australia, about 50% of the vaccinated chil- dren had local reactions (30, 31, 47, 48). Measles Immunization

Severe reactions following measles immu- nization are rare (Table 3). In the United States, neurologic disorders (including ence- phalitis and encephalopathy) have been re- ported once for approximately every million vaccine doses administered (33). However, the reported incidence of, encephalitis or ence- phalopathy following measles immunization is lower than the observed incidence of encepha- litis of unknown etiology (two cases per milhon children in 28 days-34). This sug-

194 PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 18, no. 2, 1984

Table 2. Estimated rates of adverse reaction following DPT immunization, compared to

complications of natural whooping cough.

Adverse reaction

Whoopmg cough DPT vaccme advene

complication rate reaction rate per

per 100,coo cases 100,000 immunizations

References pmwdrng data

Perr&nent brain damage

Death

Encephalopathy/enceph’alitis”

Convulsions

Shock

600-2,000 (0.6-2.0%)

loo-4,000

(O.l-4.0%)

go-4,000

(0.09-4.0%) 600-8,000 (0.6-8.0%)

-

0.3-0.6 13-18

0.2 16, 18-24

0.1-3.0 14, 16-19, 23, 25-29

0.3-90 16, 19, 22-32

0.5-30 25, 28

‘Including seizures, focal neurologic signs, coma, and Reye’s syndrome.

Table 3. Estimated rates of serious adverse reaction following measles immunization, compared to

complications of natural measles infection and the background rate of illness.

Adverse reaction

Measles complication rate per 100,ooo

case.5

Measles vaccine adverse reaction rate per 100,ooo vaccinees

Background rate of illness per 100,ooo persons

RCkWlC.3 providing data

Encephalitis/ encephalopatby Subacute sclerosing

panencephalitis Pneumonia

Convulsions

Death

50-400 0.1 0.1-0.3 33-35

(0.05-0.4%)

0.5-2.0 0.05-O. 1 - 16, 27, 36

3,800-7,300 - - 16, 35

(3.8-7.3%)

500-1,000 0.02-190 30 16, 27, 32, 34

(0.5-1.0%) 35, 37-39

lo-10,ooa 0.02-0.3 - 16, 20, 33, 35, 40

(O.Ol-10%)

gests that some of the reported severe neurolo- gic disorders may not be caused by measles immunization, but instead may be related only in time. In the United Kingdom, how- ever, the National Childhood Encephalopathy Study found a statistically significant associa- tion between the onset of acute neurologic ill- ness and measles immunization given 7 to 14 days before the onset of illness, compared with controls. The relative risk for this period was estimated to be 2.5 times the background rate (19

Some 5- 15 % of measles vaccinees develop a temperature of 39.4’C or higher, beginning on the sixth day and usually lasting one or two days. Transient rash may occur in about 5% of the vaccinees (33).

Measles immunization, by preventing natural measles, reduces the risk of developing subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE) (33).

Poliomyelitis Immunization

l ABSTRACTS AND REPORTS 195

the United States, the reported risk of paraly- sis among vaccinees or their close contacts has been one case per 3.2 million doses distributed PO)-

No serious adverse reactions to the inacti- vated poliomyelitis vaccines currently in use have been reported.

Immunization of I11 or Malnourished children

Health personnel are understandably cau- tious in offering immunization to any child who is not healthy. Nevertheless, as already noted, such children may be particularly benefited by immunization, and in most cases the immunization is safe and effective.

The most ample literature on this subject concerns measles immunization. Several studies have investigated measles immuniza- tion of malnourished or ill children. McMur- ray and coworkers (51) studied serum anti- body responses and reaction rates to measles vaccine in normal and moderately malnour- ished ten-month-old Colombian children. The children were followed for more than a year. The malnourished children showed high measles antibody responses and had no more adverse reactions than well-nourished chil- dren. The authors concluded that measles vac- cine was both safe and effective in moderately malnourished children.

Ifekwunigwe and coworkers (52) studied serum antibody responses and adverse reac- tions following measles immunization of mal- nourished Nigerian children five months to nine years old. They found that malnutrition did not impair the children’s serologic re- sponses; of 111 children who were seronega- tive before immunization, 94% serocon- verted. There were no major adverse reac- tions to immunization during the eight-week followup period. The authors concluded that malnutrition should be a prime indication for measles immunization rather than a contrain- dication, because antibody responses are nor-

mal and because natural measles is often severe in malnourished children.

In most other studies, nutritional status ap- pears to have had no significant effect on measles seroconversion rates when measles vaccine was administered alone (53-56) or simultaneously with DPT vaccine (56). In one investigation, however, children with severe kwashiorkor had impaired responses to measles immunization as compared to the re- sponses of well children (57).

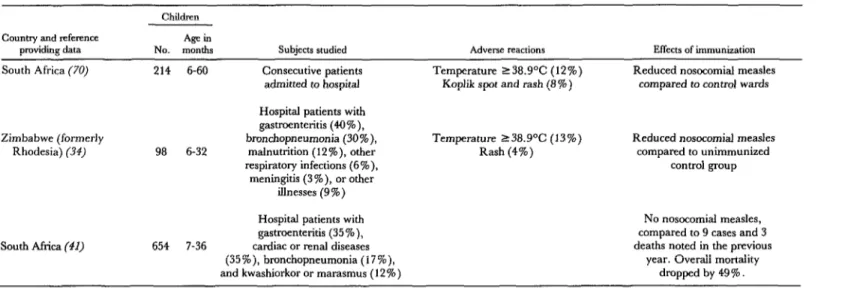

The results of three studies on measles im- munization of ill hospitalized children (58-60) are shown in Table 4. The studies were con- ducted in hospital pediatric wards during ef- forts to control hospital-acquired measles, a cause of high morbidity and mortality. Chil- dren with a wide range of acute and chronic illnesses were included; reasons for exclusion were a terminal illness, a history of measles, steroid therapy, or an immunologic disorder. The authors concluded measles immunization of ill or malnourished children did not appear to adversely affect the course of the children’s illnesses, and that the risk of measles cross- infection in pediatric wards practicing measles immunization was diminished considerably.

In the Ivory Coast a policy of immunizing sick children was introduced in 1981 (61). All children between nine and 35 months of age visiting health centers because of illness other than measles were screened; if unimmunized against measles, they were immunized. The introduction of this new policy resulted in a near-doubling of the number or doses of measles vaccine administered, from 26,000 to 45,000 doses over comparable six-month periods.

Limited data are available concerning use of other EPI vaccines in malnourished or ill children. The use of DPT (62), BCG (9), and poliomyelitis (63) vaccines in moderately mal- nourished children appears to be safe.

Table 4. Responses of ill African children to measles immunization, as indicated by three studies.

Children

Country and teference Agein

providing data NO. months

South Africa (70) 214 6-60

Subjects studied

Consecutive patients

admitted to hospital

Adverse reactions

Temperature 238.9”C (12%)

Koplik spot and rash (8 % )

Effects of immunization

Reduced nosocomial measles

compared to control wards

Zimbabwe (formerly

Rhodesia) (34)

Hospital patients with

gastmenteritis (4O%),

bronchopneumonia (30%), Temperature 138.9’C (13%) Reduced nosocomial measles

98 6-32 malnutrition (12%), other Rash (4%) compared to unimmunized

respiratory infections (6%), control group

meningitis (3%), or other

illnesses (9%)

south Africa (41)

Hospital patients with No nosocomial measles,

gastmenteritis (35%), compared to 9 cases and 3

654 7-36 cardiac or renal diseases deaths noted in the previous

(35%), bronchopneumonia (17%), year. Overall mortality

l ABSTRACTS AND REPORTS 197

Responses to tetanus toxoid of malnour- ished children also appear to be normal (62, 67, 68). Sick children with respiratory infec- tions, gastroenteritis, or febrile illness (exclud- ing malaria) appear to respond like healthy controls to tetanus toxoid (69). Malaria has been shown in some studies to inhibit the anti- body response to tetanus toxoid (67, 69, 70). In two of these studies, however, (69, 70), only one or two doses of unadsorbed tetanus toxoid (rather than adsorbed tetanus toxoid) were given. In more recent studies (71, 72), malaria was found to have no major effect on the serologic response to adsorbed tetanus toxoid, measles, or DPT vaccines. There is no evidence of increased rates of adverse reac- tions following immunization of children who have malaria.

Serum neutralizing antibody titers follow- ing a single dose of trivalent oral poliomyelitis vaccine have been found similar in malnour- ished and well-nourished children (54, 73). However, in malnourished children secretory IgA antibody was detected significantly less often, its appearance was delayed, and the observed levels were significantly lower.

Considerable evidence suggests that injec- tions, including immunizations, may provoke paralysis in the injected limbs of children who are in the incubation period of polio infection. This partly explains why authorities in some areas without poliomyelitis immunization programs have recommended that DPT be withheld from febrile children. Even though a small risk of injection-provoked paralysis may exist in polio-endemic areas, however, fever is neither a sensitive nor a specific sign of polio infection. It thus seems likely that withholding DPT immunization from febrile children would result in far more deaths from pertussis than prevented cases of injection-provoked poliomyelitis. However, concern about injection-provoked poliomyelitis does provide a strong argument in favor of providing polio immunization simultaneously with DPT at an early age, before infants are at high risk of ex- posure to wild polio virus.

National Policies Concerning Contraindications to Immunizzkm: Agreements and Disagreements

The countries of the world have adopted similar policies with respect to certain possible contraindications to immunization and dif- ferent policies with respect to others. Policies are often based on theoretical concerns rather than facts, and needed data frequently are lacking. There is general agreement that im- munization should be deferred in the presence of a severe febrile illness (14,74). The reasons are to avoid the risk of superimposing possible adverse effects from the vaccine on the under- lying febrile disease, and to avoid a manifesta- tion of the illness being attributed to the im- munization.

There is also a consensus that vaccines re- quiring multiple doses, such as DPT, should not be repeated if a severe reaction occurred after a previous dose. Such reactions include collapse or a shock-like state, persistent screaming episodes, a temperature above 40.6%, convulsions, severe alterations in consciousness or other neurologic symptoms, and anaphylactic reactions. In the case of DPT, subsequent immunization with diph- theria and tetanus is recommended. Local reactions at the site of the injection or mild fever do not by themselves preclude the fur- ther use of DPT or other vaccines.

Also, live vaccines should not be ad- ministered to persons with immune deficiency diseases or to persons &hose immune response may be suppressed because of leukemia, lym- phoma, generalized malignancy, or therapy with corticosteroids, alkylating agents, anti- metabolic agents, or retardation.

198 PAHO BULLETIN . vol. 18, no. 2, 1984

Kingdom, the Department of Health and Social Security includes untreated tuberculo- sis as a contraindication to measles immuniza- tion and recommends that children with a history of convulsions, epilepsy, or chronic heart or lung disease, as well aschildren who are seriously underdeveloped, be given measles vaccine only with the simultaneous administration of human immunoglobulin (14). The United States Public Health Service Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac- tices (ACIP), on the other hand, finds no con- vincing evidence that measles immunization exacerbates tuberculosis and concludes that the benefit of measles immunization far out- weighs the theoretical risk of such exacerba- tion (33). The ACIP recommends measles vaccine should never be administered simulta- neously with immunoglobulin and does not recognize any neurologic contraindications to measles immunization.

Gastrointestinal disturbances, including diarrhea, are considered contraindications to oral poliomyelitis immunization in the United Kingdom but not in the United States (14, 50). Likewise, a family history of neurologic disease and developmental defects are con- sidered contraindications to DPT immuniza- tion in the United Kingdom (14). In the United States an evolving neurologic disorder is considered a contraindication, but not a static neurologic disorder such as cerebral palsy or a family history of neurologic disease (25).

Recommendations of the Expanded Program on Immunization

A lack of resources-including personnel, supplies, and equipment-is the major factor constraining the delivery of effective immu- nization services in developing countries, while incomplete implementation of immu- nization policies is the main problem in in- dustrialized countries. Immunization policies that are needlessly restrictive can compound both of these problems.

It does not seem feasible or desirable to for-

mulate a universal set of recommendations for immunization of children. Each country should formulate its own policies, preferably based on the advice of a broadly constituted advisory group. The recommended national policy should reflect a practical appraisal of the disease risks, and of the benefits and potential risks of immunization. Important considerations include the availability and ac- cessibility of health care services, utilization patterns of these services, the ability to identi- fy and provide follow-up services for children who are not immunized, the likelihood that children will return for subsequent immuniza- tion, and the sociocultural acceptability of spe- cific procedures and recommendations. A list of principal recommendations that can serve as a general guide is as follows:

l Health workers should use every oppor- tunity to immunize eligible children,

l BCG can be given safely and effectively in the newborn period, while DPT and oral poliomyelitis vaccine can be given as early as six weeks after birth (or even earlier in certain circumstances). In countries where measles poses a major burden before the first birthday, measles vaccine should ordinarily be given at nine months of age.

l No vaccine is totally without adverse re- actions, but the risks of serious complications arising from the EPI vaccines are much lower than the risks posed by the natural diseases they prevent.

l The decision to withhold immunization should be taken only after serious considera- tion of the potential consequences for the in- dividual child and the community.

l It is particularly important to immunize malnourished children. Low-grade fever, mild respiratory infections, diarrhea, and other minor illness should not be considered contraindications to immunizations.

l Immunization of children so ill as to re- quire hospitalization should be deferred for a decision by the hospital authorities.

l ABSTRACTS AND REPORTS 199

receive appropriate immunization before dis- charge. (In some cases they should be immu- nized on admission, because of the high risk of hospital-acquired measles.)

l A second or third DPT injection should not be given to a child who has suffered a severe adverse reaction to the previous dose. In such cases the pertussis component should be omitted, and the diphtheria and tetanus immunizations should be completed.

l Diarrhea should not be considered a con- traindication to oral poliomyelitis vaccine; however, to ensure full protection, doses given to children with diarrhea should not be counted as part of the series, and each child should be given another dose at the first avail- able opportunity.

References

(I) Lotte, A., et al. Dev Biol Stand 43:111-119, 1979.

(2) Mande, R. JBiol Stand 5:155-158, 1977. (3) Waaler, H., and A. Rouillon. Bull Znt Union Tuberc 49:166-189, 1974.

(4) Biittiger, M., et al. Acta Paedtatr &and 71:471- 478, 1982.

(5) DahIstrom, G., and I. Sjogren. J Biof Stand 5:147-148, 1977.

(6) Gheorghiu, M., et al. Dev Biol Stand41:79-84, 1978.

(7) Goddard, N., and A. D’Souza. CAREC Sur- vdiance Repori 9:1-5, 1983.

(8) Lehmann, H. G., et al. Dev BioZStand43:133- 136, 1979.

(9) Mande, R. BCG Vaccination. Dawsons of Pall Mall, London, 1968.

(10) Mande, R., et al. Ann Pediatr 23:219-225, 1976.

(11) Rey, M. Cab Med 5,19:1141-1146, 1980. (12) Rosenthal, S. R. BCG Vaccine: Tuberculosis- Cancer. PSG Publishing Company, Littleton, 1980.

(13) Berg, J. M. Arch Dis Child 34~322-324, 1959. (14) Department of Health and Social Security. Whooping Cough: Reportsfiom the Committee on Safe9

of

Medicines and the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Zm- munization. HMSO, London, 1981.(15) Lancet. Editorial: Further contributions to the pertussis vaccine debate. Lancet 1:1113-1114, 1981.

(16) Halsey, N. A. Reactions to Commonly Used Vaccines. In: D. W. Clark and B. MacMahon (eds.). Preventive and Community Medicine (second edi- tion). Little, Brown; Boston, 1981, pp. 547-549.

(17) Miller, D. L. Current Knowledge on Pertus- sis Vaccine: Efficacy and Safety. XVII International Congress of Pediatrics, Pre-congress Workshop on Immunization, Manila, 6-7 November 1983. WHO Document WHO/IPNWP/83.9. World Health Or- ganization, 1983.

(18) Pstragowska, W., et al. Pediatr Pol (Warsaw) 44:715-721, 1979.

(19) United States Centers for Disease Control. Pertussis surveillance, 1979-1981. Morbidity and Mor- tal+ Weekly Report 31:333-336, 1982.

(20) Dittman, S. Atypische Verlat&e nach Schatzimp- finger. J Arnbrosius Barth Verlag, Leipzig, 1981.

(21) World Health Organization. Editorial: Im- munization against whooping cough. WHO Chron 29:365-367, 1975.

(22) Koplan, J. P., et al. N Engl J Med 301:906- 911, 1979.

(23) Royal College of General Practitioners. Br Med J 282:23-26, 1981.

(24) Walker, E., et al. JZnfection 3:150-158, 1981. (25) Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac- tices. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee: Diphtheria, tetanus, and per- tussis-guidelines for vaccine prophylaxis and other prevention measures. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 30:392-407, 1981.

(26) Erdos, L. Ann Zmmunol Hung 19:25-35, 1979. (27) Halsey, N. A., and H. C. Steder. Adverse Reactions Associated with Vaccines Administered in Expanded Program on Immunization Projects. In: Pan American Health Organization. Recent Ad- vances in Immunization: A Bib&graphic Review. PAHO Scientific Publication No. 451. Washington, D.C., 1983, pp. 90-102.

(28) Hannik, C. A., and H. Cohen. In: Znterna- tMnaf Symposium on Pertussis. DHEW Publication No. 79-1830. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Washington, D.C., 1979, pp. 279- 282.

(29) Zamora, D. A., et al. Rev Asoc Med Argent 76: 121-127, 1962.

(30) Cody, C. L., et al. Pediatrics 68:650-660, 1981.

(31) Feery, B. J. MedJAust 2:511-515, 1982. (32) Harker, P. BT Med J 2:490-493, 1977. (33) Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac- tices. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee: Measles prevention. Morbidity andMortality Weekly Repoti 31:217-231, 1982.

(34) Landrigan, P. J., and J. J. Witte. JAMA 223:1459-1462, 1973.

(35) Miller, C. Br Med J 1:1253, 1978.

(36) Modhn, J., et al. PedtiztlTiGs 59:505-512, 1977. (37) Medical Research Council. Br Med J 1:441- 446, 1966.

200

PAHO BULLETIN l vol. 18, no. 2, 1984(40) Benenson, A. S. (ed.). Control of Communica- ble Dtieases in Man (thirteenth edition). American Public Health Association, Washington, D.C., 1980, pp. 211-215.

(41) Department of Health and Social Security. Whooping Cough Vaccination: Review of the Evidence of Whooping Cough V&ination by theJoint Committee on VaccinationandZmmunizatton. HMSO, London, 1977. (42) Tunstall Pedoe, H., and G. Rose. Report to the Committee on Safety of Medicines: Frequency and Outcome of Febrile and Non-febrile Convul- sions in Infancy. In: Whooping Cough: Reportsjiom the Committee on SaJy of Medicines and Joint Committee on VaccinationandZmmunization. HMSO, London, 1981, pp. 50-54.

(43) Fisher, A., et al. Clin Zmmunol Zmmunopathol 17:296-306, 1980.

(44) Miller, D. L., et al. BrMedJ282:1595-1599, 1981.

(45) Bellman, M. H., et al. Lancet 1:1031-1034, 1983.

(46) Fukuyama, Y., et al. Neuropaediatrie 8:224- 237, 1977.

(47) Baraff, L. J., and J. D. Cherry. In: U.S. De- partment of Health, Education, and Welfare. Znter- national Symposium on Pertussis. DHEW Publication No. 79-1830. Washington, D.C., 1979, pp. 291- 296.

(48) Barkin, R., and M. E. Pichichero. Pediatrics 63:256-260, 1979.

(49) WHO Consultative Group. The relation be- tween acute persisting spinal paralysis and polio- myelitis vaccine: Results of a ten-year inquiry. Bull WHO 60:231-242, 1982.

(50) Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac- tices. Recommendation of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee: Poliomyelitis prevention. Morbidity and Mortal+ Weekly Repoti 31~22-34, 1982.

(51) McMurray, D. N., et al.‘Bull Pan Am Health Organ 13:52-57, 1979.

(52) Ifekwunigwe, A. E., et al. Am J Clin Nutr 33:621-624, 1980.

(53) Bhatnagar, S. K., et al. Indian Pediatr 18:625- 629, 1981.

(54) Chandra, R. K. Br Med J 2:583-585, 1975. (55) Collaborative Study by the Ministries of Health of Brazil, Chile, Costa Rica, and Ecuador and the Pan American Health Organization. Sero- conversion rates and measles antibody titers in- duced by measles vaccine in Latin American children 6-12 months of age. Bull Pan Am Health OT-

(56) Marshall, R., et al. J Trofi Pediatr 20:126- 129, 1974.

(57) Powell, G. M. Am Trap Paeddr 2:143-145, 1982.

(58) Glyn-Jones, R. Cent Afr J Med 18:4-g, 1972. (59) Harris, M. F. S Aj Med J 55:38, 1979. (60) Wagstaff, L. A. S Aj Med J 43:664-669, 1969.

(61) Coffi, E. Abstract. From a paper presented at the International Symposium on Measles Im- munization held in Washington, D.C., on 16-19 March 1982.

(62) Ghosh, S., et al. Indian Pedtiztr 17:123-125, 1980.

(63) Brown, R. E., and M. Katz. East AfrMedJ 42:221-232, 1965.

(66) Yakacikli, S., et al. Nutr Rep Intern 9:427- 431, 1974.

(64) Balch, H. H. J Zmmunol 64:397-410, 1950. (65) Havens, W. P., et al. AmJMedSci228:251- 255, 1954.

(67) Edsall, G., et al. Proceedings ofthe Fourth Inter- tiional ConfermGe on Tetanus, Dakar, 6-12 April 1975 (vol. 2). Fond. Merieux, 1975, pp. 683-685.

(68) Kielmann, A. A., et al. Bull WHO 54:477- 483, 1976.

(69) Greenwood, B. M., et al. Lanzet 1:169-172, 1972.

(70) McGregor, I. A., and M. Barr. Trans R Sot Trap Med Hyg 56~364-367, 1962.

(71) Breman, J. G., et al. Malaria and Immuno- depression: Is There an Effect on Seroconversion following Childhood Immunization? Paper pre- sented at the Annual Meeting of the American So- ciety of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, November 1982.

(72) Monjour, L., et al. Bull WHO 60:589-596, 1982.

(73) Chandra, R. K. BrMed Bull 37:89-94, 1981. (74) Advisory Committee on Immunization Prac- tices. Recommendations of the Immunization Practices Advisory Committee: General recommendation on immunization. Morbidity and Mortality Weekb Repoti 32:1-17, 1983.

Source: World Health Organization, Indications and Contraindications for Vaccines Used in the Expanded Programme on Immunization, WHO Document EPII